Published online Jan 24, 2026. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v17.i1.113966

Revised: November 22, 2025

Accepted: December 18, 2025

Published online: January 24, 2026

Processing time: 127 Days and 20.7 Hours

Myeloid sarcoma (MS) is a rare hematological malignancy that may be associated with myelodysplastic or myeloproliferative neoplasms. Herein, we report a case of transformation from myelofibrosis to MS.

A 56-year-old male patient was found to have multiple bone lesions by the pelvic magnetic resonance imaging. Pathological analysis of the lesions indicated a myeloid tumor, and immunohistochemistry revealed a TP53 mutation. Bone marrow aspiration was consistent with myelofibrosis. Based on the patient’s history of polycythemia and the immunohistochemical findings of the surgically resected lesions, a transformation from a myeloproliferative neoplasm to MS was suggested. The patient developed hematological toxicity after receiving chemo

Cases of myelofibrosis transforming into MS are extremely rare. The TP53 muta

Core Tip: This paper details the diagnosis and treatment process of an elderly male patient whose condition transformed from myelofibrosis to myeloid sarcoma. The diagnosis was confirmed through multiple examinations. This case highlights the significant impact of accurate diagnosis and flexible adjustment of treatment plans on patients' survival under complex disease conditions.

- Citation: Zhong SH, Lou J, Zhao AQ, Jin XL, Wei SM, Liang Y. Myeloid sarcoma transformed from myeloproliferative neoplasm: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Oncol 2026; 17(1): 113966

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v17/i1/113966.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v17.i1.113966

Myeloid sarcoma (MS) is a rare and distinct hematological malignancy characterized by the formation of solid tumor masses composed of myeloid blasts or immature myeloid cells in extramedullary sites, that is, outside the bone marrow. This condition is often associated with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) but can also occur independently or as a precursor to AML[1,2].

The clinical presentation of MS is highly variable, as it can occur in virtually any organ or tissue, including the skin, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, and central nervous system. This variability often leads to misdiagnosis, with MS being mistaken for lymphomas or other solid tumors. The diagnosis of MS is further complicated by its rarity and the overlapping features with other hematological disorders, such as myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) and myelodysplastic syndromes[3,4]. The main aim of this article is to present a case of myelofibrosis (MF) transforming into MS, furthering the clinical understanding of MS.

The patient was a 56-year-old male who had experienced left hip pain for over a month.

The patient developed left hip pain and discomfort more than one month ago and subsequently underwent surgical resection of the lesion.

The patient had a history of polycythemia and hypertension.

No special notes.

The patient was underweight but in fair general condition. Tenderness was noted at the left hip joint.

Laboratory test results were as follows: White blood cell count, 34.8 × 109/L; absolute neutrophil count, 31.53 × 109/L; hemoglobin, 156 g/L; platelet count, 871 × 109/L; albumin, 41.8 g/L; lactate dehydrogenase, 567 U/L; and C-reactive protein, 68.9 mg/L.

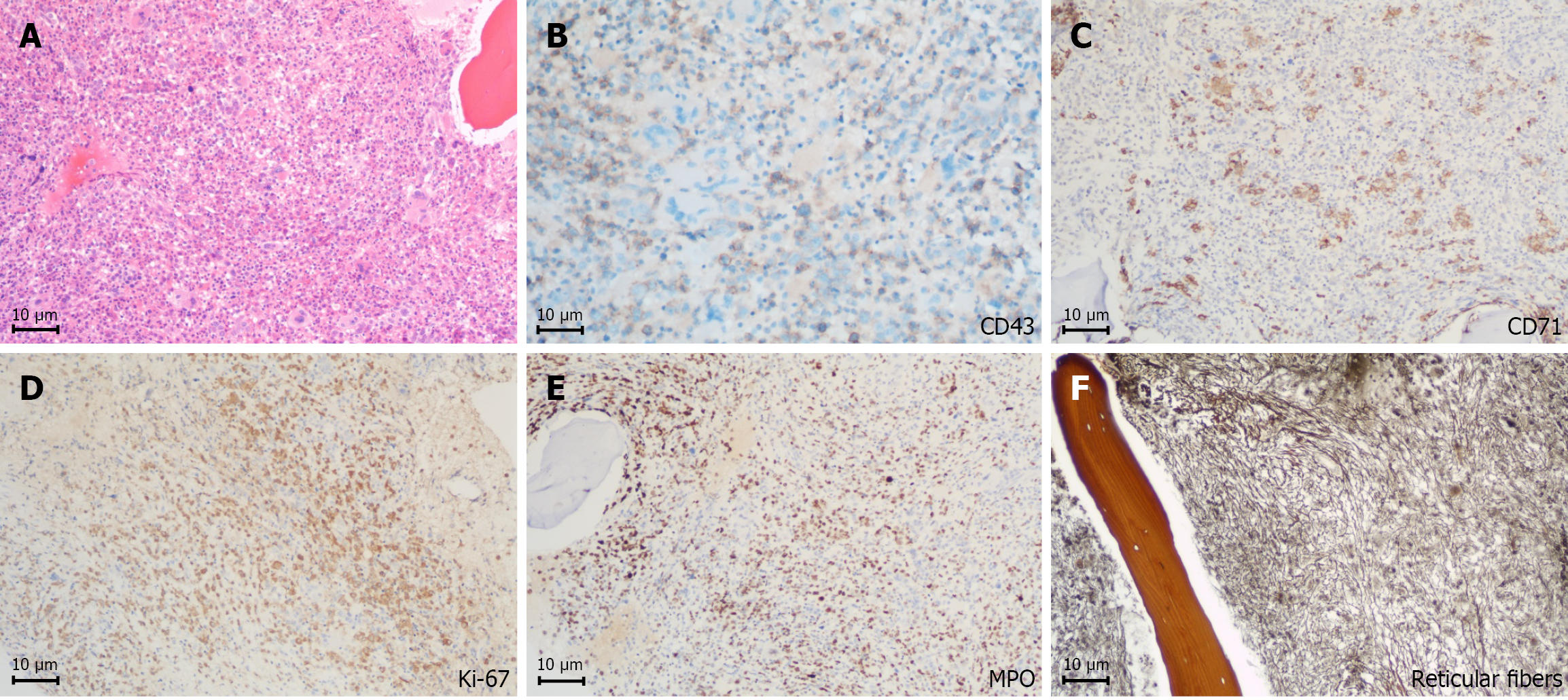

Histological examination of the puncture biopsy from the left femoral head lesion revealed abnormal cells with areas of hemorrhage and extensive necrotic tissues. These cells expressed CD43 and showed partial positivity for myeloperoxidase (MPO), while testing negative for CD20, CD19, CD79a, CD138, CD3, and CD56. A TP53 mutation was also detected, indicating a myeloid tumor. Immunohistochemical examination of the lesion tissue obtained during surgery on the left femur showed positive expression of CD71(+), CD43(+), scattered CD34(+), and focal weak expression for CD117(+). Meanwhile, negative expression was observed for CD3, CD20, CD79a, CD138, MPO, and CK-PAN. The Ki-67 index was 70% (Figure 1). Combining the immunohistochemical findings with the clinical history, the results were consistent with transformation from a myeloproliferative disease to MS.

Bone marrow analysis by cell morphology and flow cytometry showed no infiltration by myeloblasts. Bone marrow biopsy pathology indicated active marrow hyperplasia, an increased number of immature cells, and grade 2 bone marrow fibrosis. A positive JAK2 V617F mutation was subsequently detected.

The targeted next-generation sequencing panel (TruSight Myeloid Sequencing Panel, Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States) was used to establish the mutation profile. The panel targeted 54 genes and covered the full coding sequence of 15 genes and the exonic hotspots of 39 genes associated with myeloid malignancies. We identified sequence alterations with a variant allele frequency of ≥ 3%. The mutations were independently confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Using this technology, we identified clinically significant genetic variations, including TP53 p. (R248Q) (mutation frequency: 50.38%), TP53 p. (A76Cfs*73) (mutation frequency: 23.29%), and MYC amplification (amplification frequency: 8.68%).

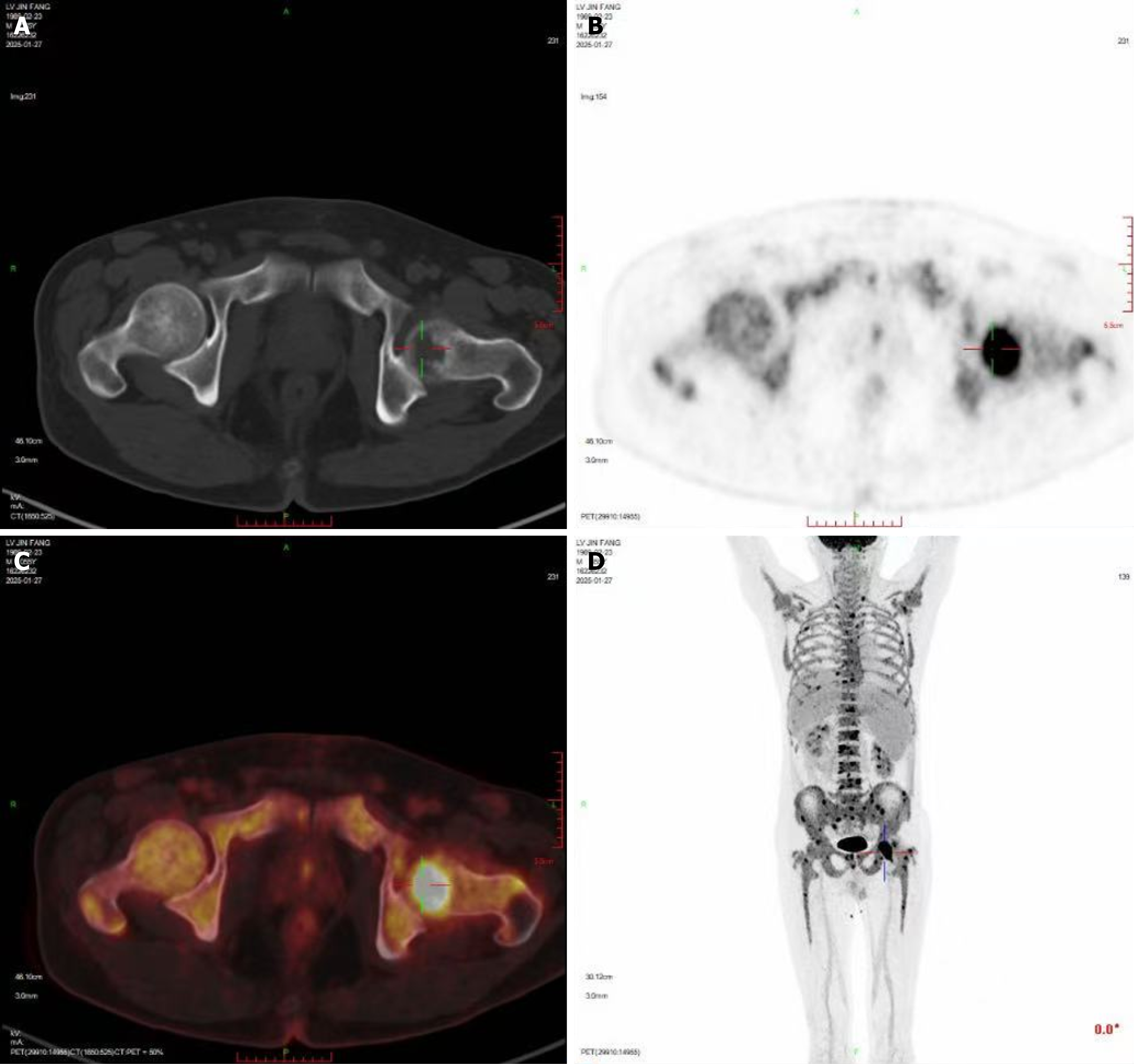

Enhanced pelvic magnetic resonance imaging revealed extensive bone signal changes in the pelvic bones, lower lumbar vertebrae, and upper segments of both femurs, suggesting a malignant tumor, possibly of hematological origin. The 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG)/and computed tomography scan showed slightly increased diffuse bone density in the axial and appendicular skeleton, multiple focal bone destructions with increased FDG uptake, mainly in the left femoral head, and splenomegaly (Figure 2).

The final diagnosis in this case was MS, which had transformed from a MPN, characterized by a TP53 mutation and MYC amplification.

The patient initially received induction treatment with idarubicin (6.5 mg/m2, days 1-3) and cytarabine (Ara-C) (100 mg/m2, days 1-7). However, severe hematological toxicity developed on the second day of chemotherapy, prompting a change in treatment to azacitidine (75 mg/m2, days 1-7) combined with venetoclax (50 mg, days 1-28). Given the patient’s poor tolerance and subsequent complications, the treatment regimen was adjusted to ruxolitinib (5 mg, twice a day) combined with low-dose venetoclax (50 mg, days 1-28).

The patient exhibited suboptimal treatment response and was lost to regular follow-up.

MS is a rare extramedullary myeloid malignant proliferative disease often associated with MPN or AML[5,6]. As shown in Table 1[7-18], among the reported cases of MPN-associated MS (MPN-MS), the vast majority originate from chronic myeloid leukemia, whereas cases based on primary or secondary MF remain relatively uncommon. In the present case, an elderly male patient presented with left hip pain. Imaging revealed extensive bone destruction and increased FDG metabolism. Pathological immunohistochemistry combined with detection of the JAK2 V617F mutation suggested transformation from grade 2 MF to MS, accompanied by TP53 mutation and MYC amplification, revealing the molecular mechanisms underlying disease progression and their correlation with prognosis.

| Age | Sex | MPN subtype | Mutations (TP53/MYC/other) | Treatment regimen | Outcome | Ref. |

| 63 | M | MDS/MPN overlap syndrome | TP53 (+); MYC (-); Complex cytogenetics (monosomies 18/19/21, 5q/7q abnormalities) | Decitabine + venetoclax → SCT | CR with complete cytogenetic response | [7] |

| 18 | M | CML | TP53 (-); MYC (-); t(9;22) (BCR-ABL1+) | Nilotinib | Alive, 2 years post-treatment | [8] |

| 39 | M | CML | TP53 (-); MYC (-); t(9;22) | Imatinib + Ara-C + high-dose dexamethasone + local radiotherapy | Dead, 2 months post-treatment | [9] |

| 49 | M | CML | TP53 (-); MYC (-); t(9;22) | Busulfan + local radiotherapy + surgery | Outcome not available | [10] |

| 50 | F | CML | TP53 (-); MYC (-); t(9;22) | Surgery + radiotherapy | Outcome not available | [11] |

| 50 | M | MPN (unspecified) | TP53 (-); MYC (-); BCR-ABL1 (+) | Dasatinib + Ara-C + SCT | Dead, 76 days post-SCT | [12] |

| 59 | F | ET | TP53 (-); MYC (-); +1, der (1;13) (q10;q10), del(7) (q22q32) | Imatinib + Ara-C + ETP | Dead, 1 month post-treatment | [13] |

| 62 | M | CML | TP53 (-); MYC (-); complex karyotype [including t(9;22)] | Imatinib | Dead | [14] |

| 63 | M | MF | TP53 (-); MYC (-); JAK2 (+) | Ruxolitinib | Dead, 10 months post-treatment | [15] |

| 60 | M | PMF, (CALR-positive) | TP53: Negative; MYC: Negative; other: CALR L367fs*46, ASXL1 E635R, KRAS A146T, SH2B3 R265Q | Death intraoperatively due to irreversible hemorrhagic shock | Death intraoperatively due to irreversible hemorrhagic shock | [16] |

| 53- | M | PMF, (pre-fibrotic) | TP53: Negative; MYC: Negative; Other: CALR type-2 (ins5-bp), NPM1 (nuclear dislocation) | Palliative splenectomy | Complete morphologic/immunophenotypic remission; subcutaneous nodules resolved; residual FDG-PET uptake | [17] |

| 51- | F | PMF, (JAK2-mutated) | TP53: Negative; MYC: Negative; other: JAK2 V617F | “3 + 7” induction chemotherapy (daunorubicin + Ara-C); consolidation with intermediate-dose Ara-C; radiotherapy (contralateral arm) | Orbital MS regression; leukemic transformation to AML; death 6 months post-diagnosis due to aspergillus pneumonia, sepsis, and multiple organ failure | [18] |

The patient had a prior history of polycythemia, and bone marrow biopsy with reticulin staining indicated grade 2 MF, reflecting the underlying lesion. The occurrence of MS is often linked to clonal evolution in the late stages of MPN. Approximately 5% to 10% of patients with MF may progress to MS[19], a process possibly driven by abnormal proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells due to JAK2 mutation and microenvironmental disturbances[20]. Herein, immunohistochemistry of the lesion showed strong CD43 expression, partial positivity for MPO, and negativity for lymphoid markers (CD20, CD3, CD79a). Combined with the absence of blast infiltration in the bone marrow, extramedullary leukemia infiltration was excluded, supporting the diagnosis of transformation from MPN to MS.

It is essential to note that the pathological morphology of MS can be easily misinterpreted as that of lymphoma, plasmacytoma, or other malignancies, and incomplete examinations may result in a misdiagnosis. Therefore, histopathological analysis of the lesion is essential for a definitive diagnosis. In this case, the positive expression of CD43 and co-expression of Kappa and Lambda light chains in the left femoral head lesion necessitated differentiation from plasma cell tumors. The absence of CD20, CD19, and CD79a ruled out B-cell lymphoma, while negativity for CD3 excluded T-cell lymphoma. Moreover, the lack of CD138 expression, partial positivity for MPO, and evidence of erythroid, myeloid, and megakaryocytic differentiation in the bone marrow excluded a plasma cell origin. Furthermore, the low expression of CD34 and CD117 indicated that the tumor cells were relatively mature, consistent with the pathological features of MF progressing to MS[21].

The TP53 mutation is a key molecular feature in this case. Its incidence in patients with MPN transforming to myeloid malignancies is approximately 10% to 20% and is often associated with disease progression and poor prognosis[22]. Studies have shown that TP53 mutation promotes abnormal proliferation of myeloid cells and treatment resistance by disrupting genomic stability[23]. As a key tumor suppressor gene, TP53 maintains genomic stability by regulating cell cycle checkpoints and apoptotic pathways; its mutation leads to loss of function, gain of oncogenic function, or dominant negative effects, thereby promoting abnormal myeloid cell proliferation and treatment resistance[24]. The coexistence of TP53 mutation and MYC amplification in this case represents a core driver of MF-to-MS transformation and therapeutic refractoriness. TP53 inactivation abrogates cell cycle control and apoptotic surveillance, enabling MYC-mediated oncogenic programs including uncontrolled proliferation and metabolic reprogramming. Synergistically, these aberrations accelerate malignant progression through epigenetic dysregulation and immune evasion[25]. At the level of therapeutic resistance, TP53 inactivation compromises drug sensitivity, whereas MYC amplification augments drug efflux and upregulates anti-apoptotic proteins—together mediating a synergistic drug-resistant phenotype[26]. Clinically, co-occurrence of TP53 and MYC abnormalities correlates with lower remission rates and shorter overall survival in myeloid neoplasms, with preclinical models validating their synergistic tumorigenic and drug-resistant effects[24]. The patient’s poor response to the regimen of idarubicin combined with Ara-C (IA) and rapid development of severe hematologic toxicity further support TP53 mutation as a potential predictor of chemotherapy resistance. The Ki-67 index, a robust marker of cellular proliferation, was 70% in this case—consistent with high-grade malignancy, indicating active tumor cell division, enhanced invasive potential, and elevated recurrence risk. This finding explains the underlying pathological basis for poor disease control and underscores the value of Ki-67 in prognostic stratification and therapeutic decision-making for MS.

For MS transformed from MPN, traditional chemotherapy regimens such as IA have low remission rates and significant toxicity[27]. For our patient, bone marrow suppression on the second day of chemotherapy. Azacitidine in combination with venetoclax is an established therapeutic regimen for TP53-mutated AML and high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes[28]. As a hypomethylating agent, azacitidine improves outcomes by restoring tumor suppressor gene expression—an effect particularly critical for TP53-mutated cells, which often exhibit exacerbated malignant phenotypes due to secondary epigenetic silencing[29]. Venetoclax targets the BCL-2 protein to induce tumor cell apoptosis and confers potential efficacy in TP53-mutated myeloid neoplasms. Thus, the patient’s treatment was adjusted to azacitidine combined with venetoclax. Despite this rationale, the present patient failed to benefit from azacitidine + venetoclax due to poor tolerance, developing recurrent fever, pulmonary infection, and metabolic encephalopathy. Given the patient’s MF background and JAK2 V617F mutation, therapy was switched to ruxolitinib (a JAK1/2 inhibitor) combined with low-dose venetoclax, based on evidence that JAK2 inhibitors enhance venetoclax sensitivity by downregulating MCL-1 expression[30]. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation was not considered due to the patient’s poor performance status and biallelic TP53 mutation, which confer high transplant-related mortality and low relapse-free survival. This clinical course highlights the urgent need for more precise, individualized therapeutic strategies for TP53/MYC co-mutated MPN-MS.

Given the high aggressiveness of MS and the patient’s high-risk molecular profile (TP53 mutation, MYC amplification), minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring holds significant clinical value. As a solid manifestation of myeloid malig

This present case highlights the importance of a multimodal approach in diagnosing MS. Combining imaging findings (bone destruction and high FDG uptake), pathological immunohistochemistry (positive myeloid markers and exclusion of lymphoid markers), and molecular testing (JAK2, TP53, MYC) can help prevent missed or incorrect diagnoses. In patients with MPN, the appearance of extramedullary masses or bone destruction should raise strong suspicion of transformation to MS, especially in those harboring TP53 mutations. For these patients, intensive treatment should be initiated promptly, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation considered. Future research should focus on elucidating the role of TP53 mutations and MYC amplification in MS progression and on developing targeted therapies to improve outcomes in this refractory disease.

| 1. | Campidelli C, Agostinelli C, Stitson R, Pileri SA. Myeloid sarcoma: extramedullary manifestation of myeloid disorders. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:426-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Almond LM, Charalampakis M, Ford SJ, Gourevitch D, Desai A. Myeloid Sarcoma: Presentation, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17:263-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Abedi A, Namdari N, Monabati A, Safaei A, Rajabi P, Mokhtari M. Myeloid Sarcoma: Case Series with Unusual Locations. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res. 2023;17:296-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Takeyasu S, Morita K, Saito S, Toho M, Oyama T, Obo T, Taoka K, Shimura A, Maki H, Shibata E, Watanabe Y, Suzuki F, Zhang L, Kobayashi H, Hinata M, Kurokawa M. Myeloid sarcoma and pathological fracture: a case report and review of literature. Int J Hematol. 2023;118:745-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kawamoto K, Miyoshi H, Yoshida N, Takizawa J, Sone H, Ohshima K. Clinicopathological, Cytogenetic, and Prognostic Analysis of 131 Myeloid Sarcoma Patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:1473-1483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tsimberidou AM, Kantarjian HM, Wen S, Keating MJ, O'Brien S, Brandt M, Pierce S, Freireich EJ, Medeiros LJ, Estey E. Myeloid sarcoma is associated with superior event-free survival and overall survival compared with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2008;113:1370-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mandhan N, Yassine F, Li K, Badar T. Bladder Myeloid Sarcoma with TP53 mutated Myelodysplastic Syndrome/Myeloproliferative Neoplasm Overlap syndrome: Response to Decitabine-Venetoclax regimen. Leuk Res Rep. 2022;17:100286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | van Groningen LF, Preijers FW, Jansen JH, Hebeda KM, van der Velden WJ. A "complicated" fracture: a Philadelphia chromosome-positive myeloid sarcoma of the bone. Ann Hematol. 2013;92:1287-1288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cozzi P, Nosari A, Cantoni S, Ribera S, Pungolino E, Lizzadro G, Oreste P, Asnaghi D, Morra E. Traumatic left shoulder fracture masking aggressive granuloblastic sarcoma in a CML patient. Haematologica. 2004;89:EIM15. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Gittin RG, Scharfman WB, Burkart PT. Granulocytic sarcoma: three unusual patients. Am J Med. 1989;87:345-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Campbell E Jr, Maldonado W, Suhrland G. Painful lytic bone lesion in an adult with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Cancer. 1975;35:1354-1356. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Wilson CS, Medeiros LJ. Extramedullary Manifestations of Myeloid Neoplasms. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;144:219-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tanaka Y, Nagai Y, Mori M, Fujita H, Togami K, Kurata M, Matsushita A, Maeda A, Nagai K, Tanaka K, Takahashi T. Multiple granulocytic sarcomas in essential thrombocythemia. Int J Hematol. 2006;84:413-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pullarkat ST, Vardiman JW, Slovak ML, Rao DS, Rao NP, Bedell V, Said JW. Megakaryocytic blast crisis as a presenting manifestation of chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2008;32:1770-1775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Burnham RR Jr, Johnson B, Lomasney LM, Borys D, Cooper AR. Multi-focal Lytic Lesions in a Patient with Myelofibrosis: A Case Report. Cureus. 2020;12:e7475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Coltro G, Mannelli F, Vergoni F, Santi R, Massi D, Siliani LM, Marzullo A, Bonifacio S, Pelo E, Pacilli A, Paoli C, Franci A, Calabresi L, Bosi A, Vannucchi AM, Guglielmelli P. Extramedullary blastic transformation of primary myelofibrosis in the form of disseminated myeloid sarcoma: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Med. 2020;20:313-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Orofino N, Cattaneo D, Bucelli C, Pettine L, Fabris S, Gianelli U, Fracchiolla NS, Cortelezzi A, Iurlo A. An unusual type of myeloid sarcoma localization following myelofibrosis: A case report and literature review. Leuk Res Rep. 2017;8:7-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chen N, Lin CS, Hsu YH, Huang WH, Huang CT, Lee YC. Acute Myeloid Leukemia Transformation from Myelofibrosis Upon Remission of an Orbital Myeloid Sarcoma - A Case Report. Int Med Case Rep J. 2021;14:443-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pace M, Guadagno E, Russo D, Gencarelli A, Carlea A, Di Spiezio A, Bertuzzi C, Mascolo M, Grimaldi F, Insabato L. Myeloid Sarcoma of the Breast as Blast Phase of JAK2-Mutated (Val617Phe Exon 14p) Essential Thrombocythemia: A Case Report and a Systematic Literature Review. Pathobiology. 2023;90:123-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shafi S, Mohanty SK, Williamson SR, Sharma S, Akgul M, Sangoi AR, Arora S, Acosta AM, Panda SS, Mishra SK, Deshwal A, Jha S, Mallik V, Lobo A, Dixit M, Kaushal S, Quiroga-Garza G, Cheng L, Shana'ah A, Parwani AV, Jaiswal AG, Dhillon J, Biswas G, Satturwar S. Myeloid sarcomas of the genitourinary tract: A multi-institutional study of sixteen tumors with review of literature. Pathol Res Pract. 2025;272:156106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Loscocco GG, Vannucchi AM. Myeloid sarcoma: more and less than a distinct entity. Ann Hematol. 2023;102:1973-1984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Luque Paz D, Jouanneau-Courville R, Riou J, Ianotto JC, Boyer F, Chauveau A, Renard M, Chomel JC, Cayssials E, Gallego-Hernanz MP, Pastoret C, Murati A, Courtier F, Rousselet MC, Quintin-Roué I, Cottin L, Orvain C, Thépot S, Chrétien JM, Delneste Y, Ifrah N, Blanchet O, Hunault-Berger M, Lippert E, Ugo V. Leukemic evolution of polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: genomic profiles predict time to transformation. Blood Adv. 2020;4:4887-4897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Garcia JS, Platzbecker U, Odenike O, Fleming S, Fong CY, Borate U, Jacoby MA, Nowak D, Baer MR, Peterlin P, Chyla B, Wang H, Ku G, Hoffman D, Potluri J, Garcia-Manero G. Efficacy and safety of venetoclax plus azacitidine for patients with treatment-naive high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2025;145:1126-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nauroy P, Delhommeau F, Baklouti F. JAK2V617F mRNA metabolism in myeloproliferative neoplasm cell lines. Blood Cancer J. 2014;4:e222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fu L, Zhang Z, Chen Z, Fu J, Hong P, Feng W. Gene Mutations and Targeted Therapies of Myeloid Sarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2023;24:338-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Nishida Y, Ishizawa J, Ayoub E, Montoya RH, Ostermann LB, Muftuoglu M, Ruvolo VR, Patsilevas T, Scruggs DA, Khazaei S, Mak PY, Tao W, Carter BZ, Boettcher S, Ebert BL, Daver NG, Konopleva M, Seki T, Kojima K, Andreeff M. Enhanced TP53 reactivation disrupts MYC transcriptional program and overcomes venetoclax resistance in acute myeloid leukemias. Sci Adv. 2023;9:eadh1436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | DiNardo CD, Jonas BA, Pullarkat V, Thirman MJ, Garcia JS, Wei AH, Konopleva M, Döhner H, Letai A, Fenaux P, Koller E, Havelange V, Leber B, Esteve J, Wang J, Pejsa V, Hájek R, Porkka K, Illés Á, Lavie D, Lemoli RM, Yamamoto K, Yoon SS, Jang JH, Yeh SP, Turgut M, Hong WJ, Zhou Y, Potluri J, Pratz KW. Azacitidine and Venetoclax in Previously Untreated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:617-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 891] [Cited by in RCA: 2032] [Article Influence: 338.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Short NJ, Daver N, Dinardo CD, Kadia T, Nasr LF, Macaron W, Yilmaz M, Borthakur G, Montalban-Bravo G, Garcia-Manero G, Issa GC, Chien KS, Jabbour E, Nasnas C, Huang X, Qiao W, Matthews J, Stojanik CJ, Patel KP, Abramova R, Thankachan J, Konopleva M, Kantarjian H, Ravandi F. Azacitidine, Venetoclax, and Gilteritinib in Newly Diagnosed and Relapsed or Refractory FLT3-Mutated AML. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:1499-1508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 53.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pullarkat V, Pratz KW, Döhner H, Recher C, Thirman MJ, DiNardo CD, Fenaux P, Schuh AC, Wei AH, Pigneux A, Jang JH, Juliusson G, Miyazaki Y, Selleslag D, Arellano ML, Liu C, Ridgeway JA, Potluri J, Schuler J, Konopleva M. Venetoclax and azacitidine in untreated patients with therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia, antecedent myelodysplastic syndromes or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2025;15:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Fan H, Wang B, Shi L, Pan N, Yan W, Xu J, Gong L, Li L, Liu Y, Du C, Cui J, Zhu G, Deng S, Sui W, Xu Y, Yi S, Hao M, Zou D, Chen X, Qiu L, An G. Monitoring Minimal Residual Disease in Patients with Multiple Myeloma by Targeted Tracking Serum M-Protein Using Mass Spectrometry (EasyM). Clin Cancer Res. 2024;30:1131-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Schuurhuis GJ, Heuser M, Freeman S, Béné MC, Buccisano F, Cloos J, Grimwade D, Haferlach T, Hills RK, Hourigan CS, Jorgensen JL, Kern W, Lacombe F, Maurillo L, Preudhomme C, van der Reijden BA, Thiede C, Venditti A, Vyas P, Wood BL, Walter RB, Döhner K, Roboz GJ, Ossenkoppele GJ. Minimal/measurable residual disease in AML: a consensus document from the European LeukemiaNet MRD Working Party. Blood. 2018;131:1275-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 722] [Cited by in RCA: 852] [Article Influence: 106.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/