INTRODUCTION

National cancer control in China was launched at the end of the 1960s[1]. Along with socio-economic development, national cancer control made apparent progress in the fields of governmental organization, financial support, and cancer registry, as well as patient aid and cancer research[2,3]. However, based on several registries in eastern China, the 5-year overall survival rate of all-site cancers was poor in the 1980s, especially for liver (1.8%), lung (3.0%), esophagus (3.3%), stomach (11.6%), and rectum (19.9%)[4-6]. Inadequate healthcare resources for specialized medical staff, massive screening, standardized therapy, and novel medicines were the most common reason for poor population survival at that time[7-9].

There was a marked increase in population survival for cancer from 2003 to 2015 was found in China, with the age-standardized 5-year overall survival rate up to 40.5%[10]. The urban-rural gap was narrowed over time, but geographical differences remained[10]. Until recently, it was understood that the fairly low proportions of early diseases might be the crucial issue in poor survival; thus, organized cancer screening was emphasized more than before[11-13]. In 2016, the plan outline for “Healthy China 2030” was issued to raise the national 5-year survival for all-site cancers by 15% increments until 2030[14]. Under this official goal, the subnational situation and domestic awareness of cancer control would be meaningful topics, which need further understanding and discussion. This review aims to provide some policy advocacy to improve domestic cancer control in China.

URBAN-RURAL DISPARITY AND HIGHER MORTALITY IN RURAL POPULATION NEEDS TO BE IMPROVED

Qi et al[15] analyzed the cancer burden between 2005 and 2020 in China based on the National Mortality Surveillance System. Especially, the subnational trend and urban-rural disparity of cancer burden was paid attention to. Previously, the National Cancer Prevention and Control Programme (2004-2010) narrowed the urban-rural gap of the heavy cancer prognostic burden[16]. However, the Mortality Indexes [= mortality/(incidence + mortality) × 100%] were estimated and rural-to-urban ratios indicated the cancer control was still unfavorable to rural area[16]. Therefore, the unfavorable situation of subnational cancer control need better understanding, due to inadequacy and imbalance of socio-economic development across China.

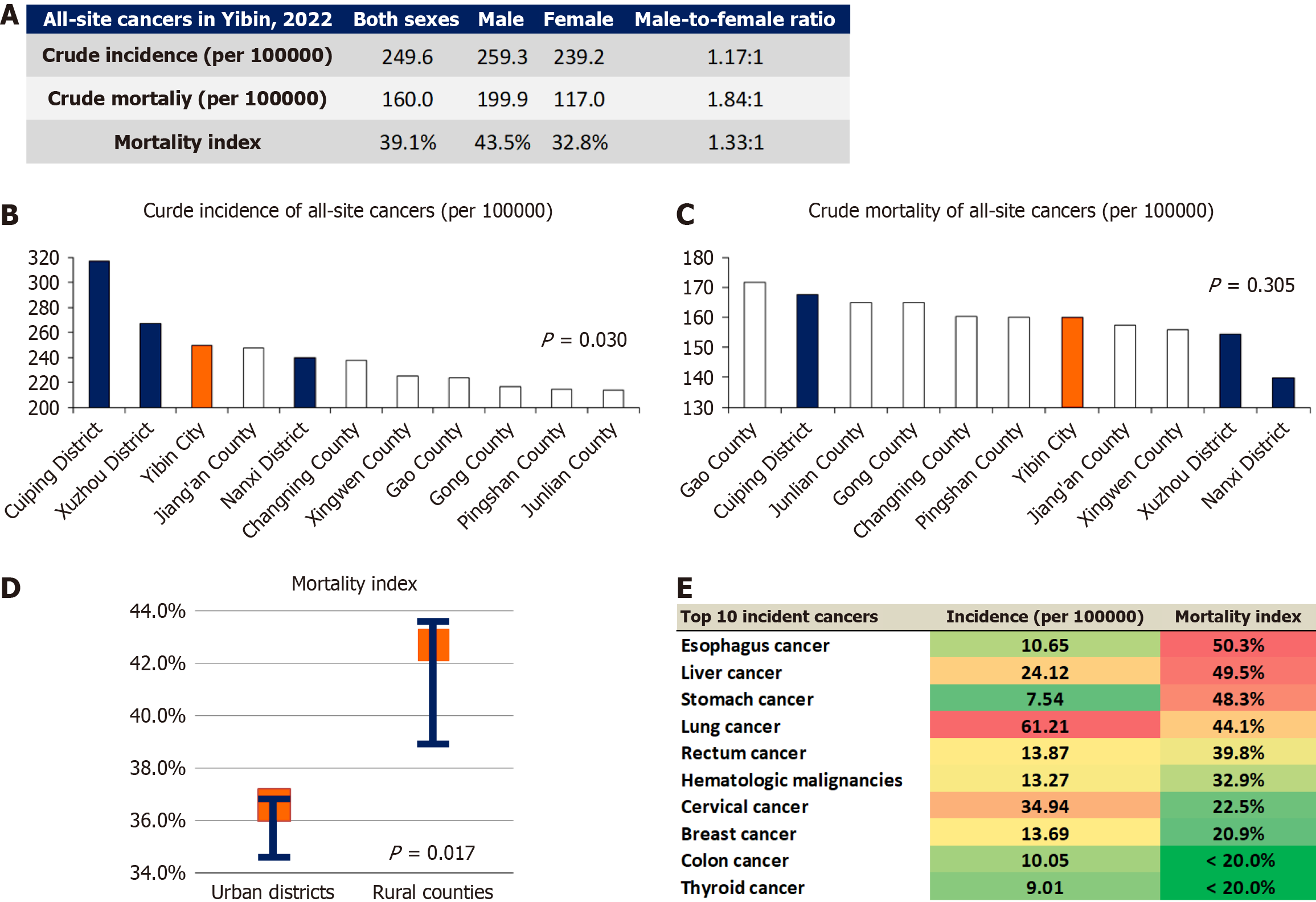

In 2022, Yibin was a fourth-line and GDP-rank top 95 city in Southwest China, with three urban districts, seven rural counties, and totally more than 4.6 million residents. The Yibin cancer registry data (2022) were retrieved from the Yibin Center for Disease Control and Prevention and analyzed according to the ICD-10 codes of cancer sites, regarding crude incidence, crude mortality, and Mortality Index[16] (Figure 1A). The percentage of death certificate only was at a low level. The crude incidence of all-site cancers was higher in urban districts compared to those in rural counties (P = 0.030, by Wilcoxon test) (Figure 1B), while crude mortality was not significantly different (P = 0.305) (Figure 1C). The Mortality Indexes of all-site cancers were higher in rural counties (median = 41.3%, range: 35.1%-41.9%) in contrast with urban districts (median = 39.8%, range: 39.5%-40.2%) (P = 0.017) (Figure 1D). Among the top 10 incident cancers, the upper digestive system (esophagus, liver, and stomach) and lung had fairly high Mortality Indexes (range: 44.1%-50.3%) (Figure 1E).

Figure 1 Cancer epidemiology based on cancer registry at Yibin, China in 2022.

A: Crude incidence, crude mortality, and Mortality Index of all-site cancers in Yibin, 2022; B: Crude incidence of all-site cancers in districts and counties; C: Crude mortality of all-site cancers in districts and counties; D: Urban-rural comparison of all-site cancers Mortality Indexes; E: The specified Mortality Indexes of top 10 incident cancers.

Through the subnational example of Yibin, it is helpful to think over the potential causality and extrapolation within broader national trends. The top incidental cancers had lower incidence rates in Yibin comparing to the nationwide averages[1,17], with the exception of lung cancer. This means that the focus of specialized cancer prevention and control must be determined at the subnational level. For example, in Western China, the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H.pylori) infection was higher among Tibetans than among Han ethnicity[18]. A more robust protocol of screening and eradication of H. pylori should be implemented among Tibetans, which would be helpful to decrease the risk of gastric cancer[14]. Higher incidence in urban area might be due to diverse factors, including environmental exposure, convenience of cancer screening and detection, personal preferences of medical care, and higher quality of cancer registry[19]. These risk factors have some universality at the subnational level, and need attention to improve urban-rural disparities. Associations of cancer incidence rate with screening accessibility and participation were not directly compared across urban and rural areas, and further research is needed to validate these issues.

Digestive system and lung cancers had a heavy fatal burden for a long time in China. The higher Mortality Indexes in rural areas of Yibin could be explained by a lower rate of early diagnosis[11-13], and lower accessibility of standardized multidisciplinary and surgical treatment, as well as novel therapies[8,16,20]. For example, the incidence of gastric cancer was relatively low in Yibin, merely around one third of the nationwide average, but its Mortality Index was fairly high in contrast. Organized massive screening and surveillance in rural area might be a more efficient approach to improve early diagnosis[21], and the generalization of public willingness to health check-up should be carried out among rural population. Subnational cancer prevention and control organizers and healthcare insurance providers should focus on increasing the proportion of early-stage cancers to improve the population survival. For example, at the policy level, it can be recommended to include screening lung and digestive system cancers into the chronic disease management directory of rural healthcare insurance.

Professional education and training of family doctors, general practitioners, internal medicine physicians, oncologists and surgeons needs consistent organization and support, especially in rural counties, towns and villages at a subnational level. The number of primary care and public health staff remains a major issue in the field of cancer control and prevention, and requires gradual enrichment based on developing medical education plan.

IMPROVED MEDICAL EDUCATION AND PUBLIC HEALTH EDUCATION: TO INCREASE DOMESTIC AWARENESS OF CANCER CONTROL

Epidemiological data from cancer registry show that geographic inequalities and urban-rural disparities do exist. The low proportion of early-stage cancers may be a major factor in the poor cancer survival rates. Therefore, it is important to increase the nationwide awareness of cancer control both among healthcare providers and the public, especially to improve the provision and willingness of cancer prevention and screening services.

“Healthy China 2030” plans to increase the number and improve the quality of general practitioners and resident trainees in the medical education system[22,23]. In particular, there is a shortage of general practitioners in China, as well as healthcare staff in the community and in rural areas[24]. Traditionally, cancer prevention and control have not been part of the medical education curriculum. With the development of medical education and standardized resident training in China, integrating knowledge of cancer symptomatology and screening protocols into basic professional training is needed to support competency in cancer control.

A deep understanding of cancer symptomatology and screening protocols can help physicians perform better in either opportunistic or organized massive cancer screening. Zakkak et al[25] analyzed the English National Cancer Diagnosis Audit 2018 data, including 55122 newly diagnosed cancer patients, and associations between specified symptoms and site-specific cancers were found. Patients > 60 years and > 75 years accounted for 75.7% and 36.5% of the total, respectively. Only around 10%-30% of incident cancer patients appear asymptomatic, with the exception of ocular cancer[25].

Several topics in medical education can be specifically recommended to develop cancer control in China. First, the medical education system can be optimized through supplementing the content of cancer control into compulsory courses and clinical/social practice. Medical undergraduates of any specialty can obtain basic knowledge, training, and experience of cancer prevention and control. Second, it is necessary to consider the quality and number of personnel in cancer control professions. Master’s and doctoral degrees in medicine and public health could be approved in the field of cancer control, and comprehensive training and postgraduate education of primary health workers, including family doctors, in cancer control should also be encouraged. Third, sharing international expertise and experience can help integrate cancer control into medical education.

It is also important that the public receives health education about symptoms and screening recommendations for cancer. Public health education could improve awareness of timely symptom-driven seeking of health care, which could potentially improve the rate of early diagnosis. “Healthy China Campaign-Cancer Prevention and Control Practice Program (2019-2022)” proposed that public awareness rate of core knowledge about cancer control should be no less than 70% by 2022. According to the sequential questionnaire survey of Sichuan Cancer Prevention and Control Center, the overall awareness rate of core knowledge about cancer control among the public samples has apparently increased from 50.1% to 77.5% during 2018 to 2022 in Sichuan province[26]. However, cancer control awareness is still inadequate and unbalanced. For example, until 2022, the warning signs of breast cancer were only recognized by 37.0% of the interviewees. In our unpublished cross-sectional survey in Ya’an city, Sichuan province in 2024, 44.9% of participants had never undergone cancer screening or specific health checks, and 5.1% were unsure.

In cancer control in China, the emphasis is till on treatment more than prevention, screening and surveillance on high-risk subpopulations[27]. Organized medical education of professionals about cancer symptoms, risk factors and screening protocols would be helpful for tertiary prevention[25,28]. Public health education about cancer control is also needed. First, the program should be officially organized as comprehensively as possible in accordance with “One Health”, covering high prevalence or less-developed areas[16]. Second, tailored strategies of health education need to be designed for specific subpopulations, such as elderly, rural, or less-educated persons, as well as for cancers with rapidly increasing incidence. Third, diverse approaches and patterns can be attempted through novel media, community management, and artificial intelligence, e.g., online self-testing questionnaire of symptoms and risk factors, along with organized participation[25]. In candidate villages in pilot program of cancer control education, some modern approaches of information technology can be attempted and validated. Last, it must be recognized that translation from health education to declining cancer incidence and mortality is a long-term goal. Therefore, the health education for cancer control should be embedded into the national education system. It is expected that these measures will lower cancer incidence and increase proportion of early-stage cancers in China during the next decade.

CONCLUSION

Cancer control has systematically achieved a lot in China in recent decades, but one of the crucial issues is the low proportions of early-stage diseases among leading cancers. Subnational cancer control has diverse and specific features in China, and especially in rural areas, it needs support to improve screening accessibility and medical quality. Besides, the nationwide awareness of cancer control might be another important direction to enhance the early detection, both among public healthcare providers and the public. Finally, the primary prevention of cancer should be consistently enhanced[29].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Sichuan Gastric Cancer Early Detection and Screening project supported the work. The work was represented at the 16th Annual Meeting of Chinese College of Surgeons (CCS2023), Chinese Medical Doctor Association, Shanghai, China, July 13-16, 2023. The cancer registry data were provided by the Yibin Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade A, Grade A, Grade B, Grade B

Novelty: Grade A, Grade A, Grade B, Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade A, Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade A, Grade A, Grade B, Grade C

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Guo SB, MD, PhD, China; Wang N, MD, Postdoctoral Fellow, United States S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang L