INTRODUCTION

The incorporation of advanced endoscopic techniques into hepatology has given rise to the evolving discipline of endo-hepatology[1]. This field is anchored on two principal domains: The first addresses disorders of the liver parenchyma, vascular abnormalities, and portal hypertension (PHTN), primarily evaluated through endoscopic ultrasound (EUS); The second focuses on the hepatobiliary tract using endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), EUS, and enhanced imaging modalities[1]. Currently, endoscopic screening and therapeutic interventions for gastroesophageal varices (GOVs), as well as ERCP in the context of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and post-transplant biliary complications, constitute the most prominent intersections between hepatology and endoscopy[1]. Expanding applications within this field now include EUS-guided liver biopsy (LB), EUS-guided portal pressure gradient measurement, coil and glue embolization of gastric varices (GVs), and cholangioscopy[2]. As interest in endo-hepatology continues to grow, hepatologists must become familiar with its diverse applications[2]. This review offers a comprehensive synthesis of current clinical evidence and procedural innovations, while also exploring emerging areas such as artificial intelligence (AI) in endoscopic imaging, therapeutic integration, and applications in liver transplantation (LT).

Endoscopic evaluation and management of gastroesophageal and GVs

Bleeding from GOVs remains one of the most severe and life-threatening complications of cirrhosis, with a mortality rate of approximately 15% over the past decade despite substantial therapeutic advances[3]. Baveno IV consensus reported that stage 1 no varices or ascites, mortality rate is 1%, stage 2 varices without ascites and without bleeding, mortality rate is 3.4% per year, stage 3 is characterized by ascites with or without varices but never bled, mortality rate is 20% per year, stage 4 is characterized by gastrointestinal bleeding with or without ascites, in this stage the one year mortality is 57% and nearly half of these deaths occur within 6 weeks from the initial episode of bleeding[4]. Historically, routine screening for GOVs has been recommended in all patients with cirrhosis to identify high-risk varices, defined as medium to large varices or small varices with red wale signs[5]. In patients with high-risk varices, endoscopic band ligation (EBL) and preferably non-selective beta blockers (NSBBs) are considered acceptable strategies for primary prevention[5]. The most recent Baveno VII consensus in 2021 expanded the preventive scope beyond variceal hemorrhage to encompass clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH)[3]. Within this revised framework, liver stiffness measurement (LSM) and platelet count thresholds were proposed to stratify risk among patients with compensated advanced chronic liver disease related to alcohol, viral hepatitis, or non-obese non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. CSPH is ruled out when LSM is below 15 kPa and platelet count exceeds 150000 per microliter, and is ruled in when LSM exceeds 25 kPa[3]. In the presence of CSPH, Baveno VII recommends the use of NSBBs to prevent first hepatic decompensation, even in the absence of varices[6]. In cases of suspected acute variceal bleeding, prompt intervention is critical. Recommended measures include intensive monitoring of vital signs, early administration of prophylactic antibiotics and vasoactive agents, judicious volume resuscitation guided by a restrictive transfusion strategy targeting a hemoglobin level below 7 g per deciliter, and urgent endoscopic hemostasis within 12 hours of onset[3,7]. For GVs, cyanoacrylate injection remains the preferred endoscopic therapy over EBL due to its higher immediate hemostasis rates and lower rebleeding risk up to 2.6 to 4.1 times lower[7]. GVs account for 10% to 15% of all variceal hemorrhages in cirrhosis and are commonly associated with pre-hepatic PHTN, including causes such as portal or splenic vein thrombosis and schistosomiasis[8]. Although GVs bleed less frequently than esophageal varices, when bleeding does occur, it is often more catastrophic[9]. Cyanoacrylate remains the gold standard for both acute hemostasis and secondary prophylaxis of gastric variceal bleeding[3]. However, obliteration rates are variable, ranging from 44% to 100%[10]. The procedure is not without risk, with potential complications including systemic embolization (0.5% to 4.3%), extrusion-associated ulceration with bleeding (4.4%), needle entrapment, and infectious complications such as septic thrombophlebitis[11]. Despite its established role, endoscopic treatment of GVs remains challenging and less satisfactory compared to esophageal variceal management[11]. The use of thrombin or hemostatic powders for definitive treatment of acute variceal bleeding, whether esophageal or gastric, is not currently recommended[7]. However, these agents may be considered as a bridge to definitive therapy when conventional measures are unavailable or ineffective, or as adjunctive treatment in post-EBL ulcer bleeding[12].

ENDOSCOPY UTILITY IN LT

Pre transplantation upper endoscopy

Patients with end-stage liver disease undergoing evaluation for LT are at considerable risk for severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding, including from esophageal varices, GVs, and portal hypertensive gastropathy[13]. Although rare, there are documented cases of massive variceal bleeding during LT attributed to PHTN[14]. Encouragingly, LT has been shown to reduce the risk of esophageal varices bleeding and improve the overall profile of PHTN[15]. Endoscopic studies have demonstrated a high prevalence of varices among LT candidates, with a substantial proportion presenting with large esophageal varices, portal hypertensive gastropathy in more than 50% of cases, and GVs in up to 16%[16]. Despite strong recommendations advocating upper endoscopy for all cirrhotic patients to assess the presence and grade of varices for primary prophylaxis planning[17], real-world data reveal suboptimal adherence to these recommendations. In one study, fewer than half of patients undergoing evaluation for LT had undergone screening endoscopy or appropriate imaging to detect varices[18].

Post transplantation upper endoscopy

In the early period following LT, upper gastrointestinal bleeding may occur due to prior endoscopic interventions such as band ligation or pretransplant variceal sclerotherapy[19]. Other common etiologies include peptic ulcer disease, Mallory-Weiss tears, gastroduodenal ulcers, and stress-induced gastropathy superimposed on portal hypertensive gastropathy. Additionally, patients who have undergone Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy may experience bleeding originating from intestinal or biliary anastomoses[19]. Upper endoscopy should be considered in the evaluation of posttransplant gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly in the presence of bleeding, dysphagia, or unexplained gastrointestinal complaints. Cytomegalovirus infection may affect the entire gastrointestinal tract and present with a broad spectrum of symptoms, including dysphagia, nausea, bleeding, or diarrhea[20]. Opportunistic infections such as esophageal candidiasis and herpes simplex esophagitis may also occur and commonly present with dysphagia or odynophagia[21].

Pre transplantation lower endoscopy

Lower gastrointestinal symptoms in patients being evaluated for LT should be assessed with colonoscopy. In one study, 56 out of 118 transplant candidates underwent colonoscopy due to anemia, lower gastrointestinal symptoms or abnormalities, history of colonic polyps or inflammatory bowel disease, heme-positive stools, or age over 50 years. Among them, 24 were found to have adenomatous polyps, 60% of which were diminutive in size (less than 5 mm). Notably, one patient was diagnosed with sigmoid colon cancer, and another with chronic ulcerative colitis had a dysplasia-associated lesion or mass[22]. Interestingly, 16 of the patients who had polyps were asymptomatic, with age over 50 being the only indication for screening, and five of them had adenomatous polyps[22]. Additional studies have reported that over 20% of LT candidates undergoing colonoscopy have adenomatous polyps[16]. Given the elevated risk of colorectal cancer following LT in patients with chronic ulcerative colitis, those with PSC undergoing transplant evaluation, but without a prior history of inflammatory bowel disease, should undergo colonoscopy to establish a histologic diagnosis. These individuals will require long-term surveillance post-transplant[23].

Post transplantation lower endoscopy

Colorectal complications after orthotopic LT (OLT) are often linked to underlying ulcerative colitis, infections such as Clostridium difficile or cytomegalovirus, and adverse effects of immunosuppressive or other medications[24]. In posttransplant patients, especially those with a history of inflammatory bowel disease or cholestatic liver conditions, the emergence of diarrhea accompanied by mucus and blood should raise clinical suspicion and prompt early colonoscopic evaluation to rule out ongoing colitis[24]. For average-risk or high-risk individuals who did not undergo a screening colonoscopy before transplantation, post-recovery colonoscopy should be performed as part of standard surveillance[25]. Evidence suggests that patients who undergo LT for PSC and ulcerative colitis face a higher risk of developing colorectal carcinoma posttransplant compared to patients with a similar disease course who were not transplanted[25,26]. This increased risk has led to recommendations for more frequent surveillance, with colonoscopy intervals of six to twelve months in this patient population[23].

Evaluation of the bile ducts of the living donor

Although ERCP can provide detailed anatomical information regarding the biliary system of a living liver donor, it is no longer the preferred modality for this purpose. Non-invasive imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and multidetector computed tomographic cholangiography have largely replaced ERCP in the preoperative assessment of donor biliary anatomy[27].

Management of post transplant complications

ERCP is a well-established technique for managing biliary complications following LT, particularly in patients with duct-to-duct anastomoses. Over the past years, cumulative evidence has supported its clinical utility in this setting[28]. Post-LT biliary complications commonly addressed by ERCP include anastomotic and non-anastomotic biliary strictures (ABS), bile leaks, bile casts, choledocholithiasis, hemobilia, bile duct necrosis, ductal redundancy or kinking, and retained surgical stents[29]. Although more technically challenging, endoscopic access and intervention remain feasible in selected patients with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, albeit with a more limited role[30].

BARIATRIC ENDOSCOPY IN STEATOTIC LIVER DISEASE

The growing incidence of obesity has led to a concomitant rise in liver diseases associated with excess weight, particularly metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)[31]. Population-based studies have repeatedly highlighted a strong link between obesity and the onset of MASLD, positioning it as a key contributor to liver-related morbidity[32]. Individuals with obesity and MASLD are at a higher risk of progressing to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), with subsequent development of fibrosis, cirrhosis, and potentially liver failure[33]. A meta-analysis has shown that bariatric surgery results in notable histological improvements in steatosis, MASH, and fibrosis[34]. While surgical options have been extensively evaluated, endoscopic approaches collectively termed endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies have also demonstrated favorable outcomes in MASLD, including reductions in body weight, body mass index, waist and hip circumference, and hepatic steatosis[35,36]. Endoscopic bariatric therapies have gained traction as viable, safe, and effective alternatives to surgery[37]. Currently, the most frequently employed endoscopic interventions for obesity are intragastric balloon placement and endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty, with less-used modalities such as duodenal mucosal resurfacing, the EndoBarrier device, and primary obesity surgery endoluminal[38]. EndoBarrier therapy followed with a 48% reduction (54 IU/L to 28 IU/L)[39], and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass achieved a 28.5% decrease[40]. Surgical procedures consistently led to reductions in steatosis, NASH, and fibrosis, though the degree and timing of improvement varied[41]. Such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass achieved steatosis remission in 89%-95% of patients, especially in those with moderate-to-severe baseline steatosis (grades 2 and 3)[42].

TRENDING ENDO-HEPATOLOGY, CLINICAL APPLICATIONS OF EUS IN PRACTICE

EUS-guided LB

Although noninvasive tests and elastography are gaining traction in hepatology, LB remains a pivotal tool, particularly for establishing a definitive diagnosis in cases of unexplained parenchymal disease or focal liver lesions, and for grading hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. Traditional approaches to LB include the percutaneous-LB (PC-LB) and transjugular-LB routes, both of which are invasive and carry risks such as severe pain, hemorrhage, pneumothorax, and inadvertent sampling of non-hepatic tissue[43,44]. Recent advances in endoscopic technology and equipment have led to the emergence of EUS-guided LB (EUS-LB)[45]. EUS-LB offers a compelling alternative for obtaining liver tissue, with demonstrated advantages in safety, patient comfort, and tissue yield even in pediatric age group[46].

EUS-LB allows targeted and bilobar tissue acquisition under continuous ultrasound and doppler guidance. Additionally, it can be performed alongside portal pressure gradient measurement, endoscopic evaluation for GOVs, and other upper endoscopic procedures during the same session[47]. Patients often report less procedural discomfort, lower post-procedure pain, and faster recovery with EUS-LB, which is typically performed under sedation, in contrast to PC-LB, which is often done without sedation due to its brief duration[48]. Notably, bilobar EUS-LB often yields superior specimen quality and may help mitigate the sampling variability inherent to PC-LB[44,49]. These findings have been reinforced by a recent meta-analysis of retrospective studies[49]. To date, only one randomized trial has compared PC-LB to EUS-LB, reporting greater reliability and lower cost for the percutaneous approach[50]. However, that study has been widely criticized for methodological flaws, particularly the use of suboptimal EUS-LB techniques[51,52]. EUS-LB has demonstrated a favorable safety profile, with a reported complication rate of just 0.9%, primarily self-limiting subcapsular hematoma[52]. Contraindications to EUS-LB include thrombocytopenia with platelet counts below 50000 per microliter, an international normalized ratio greater than 1.5, and massive ascites, where the transjugular route is preferred[53].

EUS guided fine needle aspiration and fine needle biopsy

EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) has become a routine method for acquiring tissue samples from a wide range of solid gastrointestinal lesions, including pancreatic tumors, subepithelial masses, and lymph nodes (LNs) within the chest or abdomen[54]. While widely implemented in clinical practice, the diagnostic accuracy of this technique is variable and influenced mainly by the nature of the target lesion, with reported yields ranging from 49% to 100%[54]. Multiple factors contribute to this variability, such as the choice of needle type and size, the number of sampling passes performed, the location and histological features of the lesion, the use of rapid onsite evaluation (ROSE), and the proceduralist’s level of expertise[55]. While some studies have demonstrated improvements in diagnostic performance through optimization of these variables, the overall benefit has not been consistent[55]. Moreover, FNA samples often fail to preserve tissue architecture, which can limit histopathologic interpretation. This poses challenges for conditions requiring immunohistochemistry, immunophenotyping, or evaluation of architectural patterns, such as lymphoma, metastatic disease, and certain subepithelial tumors[56]. Inflammatory changes may further impair cytologic interpretation, potentially leading to false positive results due to cellular atypia[57]. Fine needle biopsy (FNB) has the potential to improve diagnostic yield and may eliminate the need for ROSE in some settings[58]. A meta-analysis has shown that FNB provides diagnostic yields comparable to FNA while requiring fewer needle passes, particularly when FNA is performed without ROSE[59]. Nevertheless, high-quality comparative data remain limited, and FNB has not yet demonstrated consistent superiority over FNA across all lesion types. Accordingly, the most recent guidelines from the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in 2017 do not designate any specific needle type as preferred for sampling solid lesions[60].

EUS-guided portal pressure gradient measurement

PHTN arises from elevated pressure within the portal venous system. Cirrhosis remains the most common underlying cause, and accurate assessment of portal pressure is essential for prognostication, therapeutic monitoring, predicting postoperative outcomes, and anticipating complications in cirrhotic patients[61]. The current gold standard for portal pressure assessment is the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG), which measures pressure indirectly by advancing a catheter into the hepatic vein via the right jugular or femoral vein[61]. However, this method does not permit direct access to the portal vein (PV), and the historical percutaneous approach for direct PV pressure measurement is highly invasive and has been abandoned[62]. In addition to its invasiveness and the requirement for intravenous contrast, HVPG is unreliable in cases of pre-sinusoidal or post-sinusoidal PHTN[62,63]. EUS-guided portal pressure gradient measurement involves puncturing the middle hepatic vein, preferably due to its large diameter and favorable alignment, followed by puncture of the umbilical segment of the left PV using a 22 or 25 G needle. The pressure differential between the two veins provides an estimate of the portal pressure gradient[63,64].

EUS in detection and characterization of focal liver lesions

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging are first-line noninvasive modalities for evaluating primary and secondary hepatic lesions[65]. However, EUS demonstrates superior diagnostic accuracy for detecting small focal liver lesions, particularly those under 1 cm in size, which are frequently missed by conventional imaging[65]. Accurate characterization of these lesions is critical for preoperative planning, staging, and prognostication in cases of malignancy[66]. Evidence supports the utility of EUS as a screening tool for detecting occult liver metastases, especially within the left hepatic lobe, in patients with known or suspected primary malignancies[66]. Routine EUS examination of the liver is recommended during staging of such patients[67]. Advanced EUS techniques including elastography and contrast-enhanced ultrasound further enhance the capacity to differentiate benign from malignant focal lesions[68]. EUS elastography quantifies tissue stiffness using color mapping on standard B-mode imaging, with malignant lesions typically demonstrating increased stiffness compared to benign lesions[68]. The use of ultrasound contrast agents augments lesion characterization by enhancing visualization of microvascular architecture[69]. Contrast-enhanced EUS and contrast harmonic EUS exploit the dual hepatic blood supply and distinct vascular enhancement and washout patterns of focal lesions, enabling more precise differentiation between benign and malignant entities[67].

EUS in ascites evaluation

Ascites is a common complication of PHTN in patients with advanced liver cirrhosis; however, its differential diagnosis includes various benign (e.g., tuberculosis, renal, and cardiac ascites) and malignant causes[70]. Mortality increases from complications such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and hepatorenal syndrome, ranges from 15% in a year to 44% in 5 years[71]. Paracentesis, which is often performed with or without ultrasonographic guidance, is routinely employed for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes[70]. EUS offers a highly sensitive modality for ascites assessment, demonstrating greater sensitivity than abdominal ultrasound and CT imaging[72]. Despite its diagnostic advantage, the role of EUS in evaluating ascites among cirrhotic patients remains limited. It is generally unsafe to delay paracentesis in suspected spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in favor of an endoscopic approach[73]. In one study involving 239 patients, delayed paracentesis was associated with a 2.7-fold increase in in-hospital mortality[73]. Moreover, EUS-guided paracentesis necessitates transenteric needle passage, which may increase the risk of contamination and infection. Malignant ascites represents the second most frequent etiology of fluid accumulation in the abdomen, following advanced liver disease[74]. In this setting, EUS-guided paracentesis has demonstrated excellent diagnostic performance, with sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value reaching 94%, 100%, 100%, and 89%, respectively[75]. Furthermore, EUS permits FNA of suspicious omental or peritoneal nodules within the same session[76]. Ascitic fluid appears as an anechoic space triangular or irregular in shape on EUS, and peritoneal nodules are typically seen as heteroechoic projections within the fluid-filled cavity[76].

EUS role in management of varices

Esophageal varices are seen on EUS as spherical hypoechoic structures within the mucosa and submucosa, typically demonstrating venous waveforms on doppler imaging[77]. While EUS is less sensitive than conventional endoscopy for diagnosing esophageal varices likely due to compressing the esophageal lumen by the transducer it remains valuable for the assessment of periesophageal veins and gastric fundal varices[77]. Among patients with PHTN, the most significant clinical indication for EUS is the detection and treatment of GVs. These varices may be challenging to distinguish from thickened gastric mucosa, as they often present within the deeper submucosal layers[78]. EUS-guided coiling has been introduced as a safer therapeutic modality. One of the therapeutic approaches for managing varices involves the use of vascular coils, typically made of stainless steel or other metallic alloys, available in various sizes. When deployed, these coils promote localized thrombosis, effectively leading to occlusion of the varix[79]. An important advancement in this field came from Binmoeller et al[80], who introduced a technique that combines coil deployment with cyanoacrylate glue injection. This combined approach allows for the use of smaller volumes of glue while enhancing the efficacy of variceal obliteration and reducing the risk of glue embolization[80]. Typically, 1-2 mL of cyanoacrylate is used per session alongside the coils, depending on the size of the varix being treated[81]. Beyond GOVs, EUS has also emerged as a valuable tool for treating ectopic varices; dilated veins located outside the esophagus and stomach. These can appear in the duodenum (17%), jejunum and ileum (17%), colon (14%), peritoneum (9%), and rectum (8%)[82]. Notably, Sharma and Somasundaram[83] successfully demonstrated the use of EUS-guided glue injection for rectal varices and several case reports have supported the effectiveness of combining coiling and glue for rectal variceal management[84].

EUS elastography and shear wave applications

Real-time elastography (RTE) is an innovative technology that employs picture enhancement to elucidate variations in tissue compressibility[85]. In contrast to transient elastography (TE), RTE necessitates minimal probe compression during picture capture, as typical pressure fluctuations from neighboring vascular pulsations are generally adequate. This reduces interobserver and intraobserver variability[86]. An added benefit of RTE is its ability to provide bilobar liver assessment, whereas TE primarily evaluates the right hepatic lobe. Therefore, EUS-guided RTE may represent a feasible and superior option in patients with liver disease undergoing endoscopic evaluation for varices or abnormal liver function tests, or those who are obese, have narrow intercostal spaces, or significant ascites[64]. Beyond hepatic applications, EUS elastography plays a diagnostic role in the characterization of pancreatic masses, LNs, subepithelial lesions, and tumor staging[87]. However, reproducibility in evaluating solid pancreatic lesions remains debatable, even with the use of semiquantitative methods[88]. It is anticipated that newer quantitative techniques, such as shear wave elastography, will offer meaningful advancements in this field[89,90]. Multiple meta-analyses have demonstrated the diagnostic performance of EUS elastography in differentiating malignant from benign pancreatic tumors[91,92]. Furthermore, integrating elastography findings with contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS may improve diagnostic accuracy for solid pancreatic masses[93]. Chronic pancreatitis represents another area of interest for EUS elastography. In such patients, fibrotic transformation leads to increased tissue stiffness, whereas acute inflammation or necrotic regions typically appear softer on elastography[94,95]. EUS elastography is also valuable in assessing LNs. Benign LNs whether physiological or reactive tend to show a homogenous or heterogeneous soft elastographic pattern, often presenting as predominantly green or mixed red-yellow-green[96]. A meta-analysis reported a pooled sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 85% for EUS elastography in distinguishing benign from malignant LNs[97]. Given the limitations associated with LB, there has been increasing reliance on noninvasive testing to assess liver fibrosis. Among these, the fibrosis-4 index and vibration-controlled TE (VCTE) are the most widely used modalities[98]. VCTE utilizes shear wave propagation to measure tissue elasticity and is commonly employed to estimate liver stiffness as a surrogate for fibrosis stage (F0 to F4)[99]. In addition to VCTE, other elastographic modalities include RTE, magnetic resonance elastography, and transabdominal shear wave elastography[99]. While magnetic resonance elastography offers high diagnostic accuracy, its routine use for MASLD or MASH fibrosis screening is limited by cost constraints[98]. Moreover, VCTE tends to overestimate fibrosis severity in individuals with obesity[98], potentially resulting in unnecessary LB, delays in clinical decision-making, and increased patient anxiety.

EUS-guided ablative and therapeutic interventions

A variety of ablative techniques have been explored for the treatment of hepatic focal lesions, including alcohol injection, thermal ablation with radiofrequency, photodynamic therapy, and cryoablation[100]. Nakaji et al[101] reported the use of EUS-guided alcohol injection for a small hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) located near the inferior vena cava and hepatic veins, a location that may pose significant risks for percutaneous approaches[101]. EUS-guided injection of drug-eluting microbeads chemotherapy in the PV has emerged as one of the therapeutic option for patients with bilobar liver metastases[102]. Although this approach has shown promise in preclinical models, with agents such as irinotecan, doxorubicin, and albumin-bound paclitaxel nanoparticles demonstrating benefit in porcine studies, human data remain lacking. In a separate case report, de Nucci et al[103] reported successful EUS-guided radiofrequency ablation in two HCC patients with a background of cirrhosis[103]. They highlighted the procedural advantages of EUS over percutaneous access in cases of obesity, the presence of large intervening vessels, or tumors located in anatomically challenging regions such as the subcapsular space, caudate lobe, or left hepatic lobe[103]. Additionally, laser interstitial thermal therapy employing neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser was used in a case series involving four patients with either HCC or metastatic cancer colon. A total of ten lesions were treated using EUS-guided access, with the results demonstrating both technical feasibility and clinical safety[104].

EUS-guided liver abscess drainage

Percutaneous drainage remains the first-line approach for the management of liver abscesses. However, EUS offers a distinct advantage in cases where the abscess is located in difficult-to-access regions, such as the caudate lobe. In such cases, trans gastric access via EUS can obviate the need for an external catheter and may mitigate potential complications associated with percutaneous catheter use, including displacement[105]. EUS-guided drainage is most commonly performed for abscesses located in the left or caudate hepatic lobes[105]. Seewald et al[106] were the first to report a case of EUS-guided liver abscess drainage in 2005. More recently, a systematic review evaluated the efficacy and safety of EUS in the draining liver abscesses deemed hard to access via conventional methods, highlighting its growing role in this clinical scenario[107].

EUS-guided biliary drainage

EUS-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD) was initially introduced in 2001 by Giovannini et al[108], who successfully performed transduodenal drainage of the common bile duct (CBD) using a plastic stent[108]. Over the past period, this technique has undergone significant refinement and is now recognized as a valuable endoscopic option for managing biliary obstruction. Currently, the most common indication for EUS-BD is malignant distal biliary obstruction when ERCP is either failed or technically unfeasible[109]. Furthermore, EUS-BD has shown particular benefit in individuals with altered surgical anatomy, including those who have previously undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, or partial removal of the stomach, where accessing the ampulla through conventional endoscopy is frequently difficult[109,110]. The procedure has also been employed in patients with indwelling gastroduodenal stents that impede conventional ampullary access[111]. Multiple EUS-BD techniques exist and are classified according to the biliary access route (intrahepatic or extrahepatic), and the stent placement technique, which may be transenteric or transpappillary. The choice of technique is primarily guided by patient anatomy and the endoscopist’s expertise[112].

EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy: In EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy (EUS-HGS), an echoendoscope is positioned within the gastric body to visualize the left intrahepatic bile ducts via ultrasound guidance[112]. Following doppler evaluation to avoid intervening vasculature, a fine needle is advanced into a dilated intrahepatic duct. Once biliary access is achieved, a cholangiogram is performed to delineate ductal anatomy and confirm correct positioning. A guidewire is then introduced into the biliary system, and after tract dilation, a stent is deployed over the guidewire to establish a hepaticogastrostomy, enabling bile drainage directly into the gastric lumen[113,114]. EUS-HGS is especially beneficial for patients with altered upper gastrointestinal anatomy or luminal obstruction, such as those with previous pancreaticoduodenectomy or Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy[112]. However, its utility may be limited in patients without intrahepatic ductal dilation or with right-sided biliary obstruction[114]. Relative contraindications include coagulopathy, significant ascites, and gastric wall pathology (e.g., ulceration or tumor). The most frequently reported complications are infection (including cholangitis, pancreatitis, or biliary peritonitis), bleeding, and bile leakage[112].

EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy: In the EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy (EUS-CDS) procedure, the echoendoscope is carefully advanced into the duodenal bulb to visualize the extrahepatic bile ducts under real-time ultrasound imaging[113]. Once the target is identified, a needle is used to puncture the bile duct, followed by the injection of contrast to create a cholangiographic image. A guidewire is then inserted and navigated into the common hepatic duct or the CBD to facilitate further intervention[115]. Subsequently, a fistulous tract is created using electrocautery or dilation, and a stent is deployed to facilitate bile drainage[115]. Unlike EUS-HGS, which results in a transgastric stent accessing the intrahepatic bile ducts, EUS-CDS yields a transduodenal stent draining the extrahepatic biliary system[113].

EUS-guided antegrade stent placement: While both EUS-HGS and EUS-CDS involve creating an internal connection for biliary drainage through the gastrointestinal tract, EUS-guided antegrade stent placement provides an alternative technique to achieve biliary drainage across the papilla. In this approach, the endoscopist accesses either the intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile ducts through the stomach or duodenum under EUS guidance. Once access is confirmed, a guidewire is passed through the obstructed segment and advanced through the ampulla to complete the procedure[112,115]. EUS-guided antegrade stenting holds a theoretical advantage over EUS-HGS and EUS-CDS, as it avoids the creation of a transluminal anastomosis at the site of biliary access and may thereby reduce related adverse events[109]. This approach may be particularly advantageous in patients with surgically-altered anatomy, such as those with a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, that retain intact ampullary function. Nevertheless, the risk of post-procedural pancreatitis or cholangitis may be relatively higher than with EUS-HGS or EUS-CDS[109].

EUS-guided rendezvous technique: Similar to antegrade stenting, the rendezvous technique begins with EUS-guided access to the biliary tree, followed by advancement of a guidewire across the obstruction, through the ampulla, and into the small intestine[113]. The wire is left in place, and a duodenoscope is then introduced into the second portion of the duodenum, where the guidewire is used to facilitate successful ampullary cannulation. This enables a standard ERCP to be completed[109].

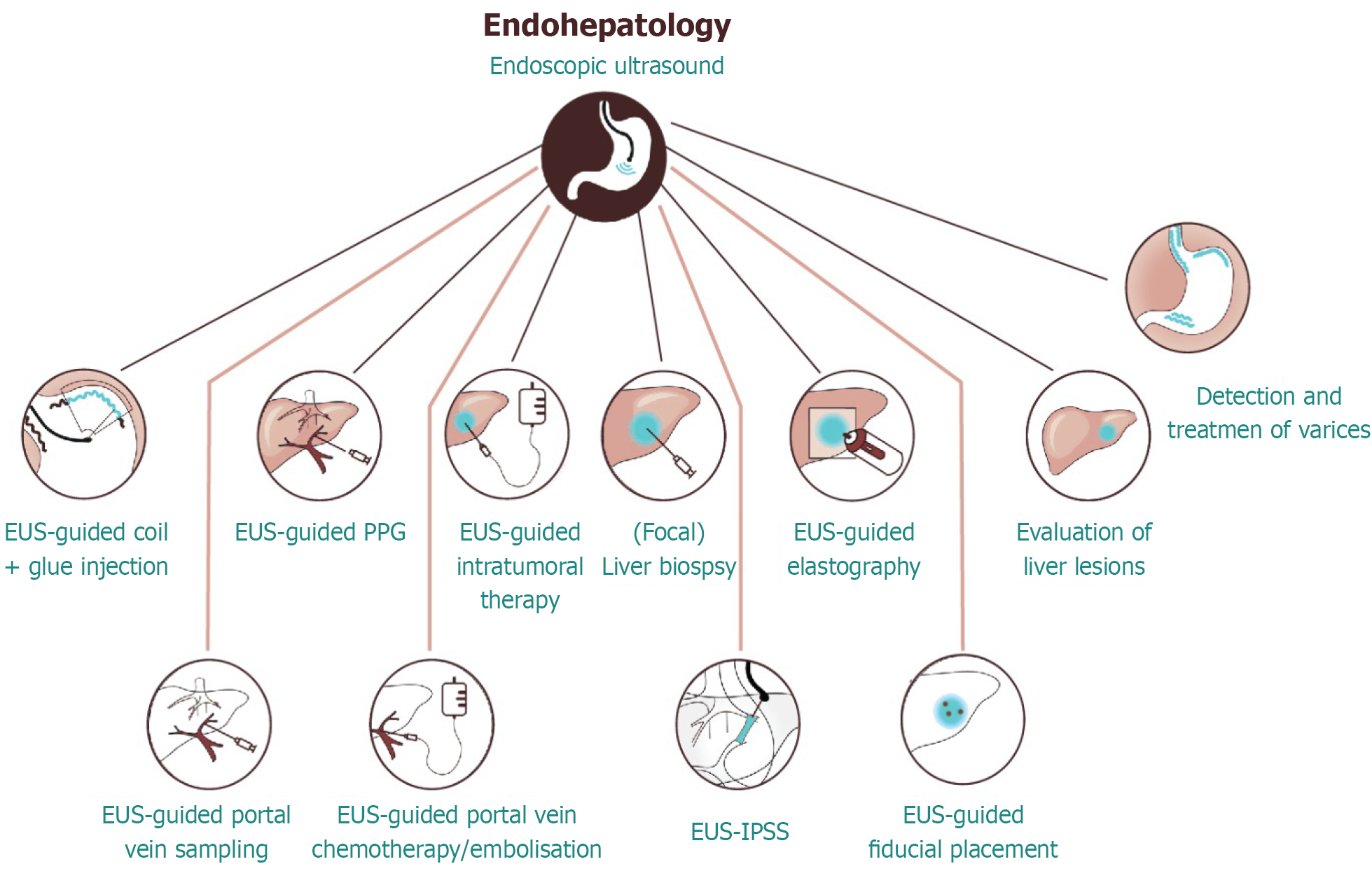

This technique permits transpapillary drainage without the need for transluminal stenting or creation of a new anastomosis, and it is beneficial in patients with an accessible duodenum but difficult conventional cannulation[113,115]. Despite the advantages of EUS-BD, including its ability to circumvent failed ERCP, its widespread adoption remains limited. This is primarily due to the requirement for advanced operator expertise relative to percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, which is more commonly performed in many settings[114]. Compared with ERCP and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, EUS-BD is a relatively recent therapeutic innovation, practiced predominantly in high-volume tertiary centers[116]. An overview of current and emerging applications of EUS in endo-hepatology is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Endohepatology: Advanced applications of endoscopic ultrasound.

This schematic demonstrates the expanding role of endoscopic ultrasound in hepatology, referred to as endohepatology. Key diagnostic and therapeutic interventions include endoscopic ultrasound-guided liver biopsy, portal pressure gradient measurement, elastography, intratumoral therapy, portal vein sampling, and treatment of varices. These innovations bridge endoscopy with hepatology and are reshaping the clinical management of parenchymal and vascular liver diseases. EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound; PPG: Portal pressure gradient; IPSS: Intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation.

TRENDING ENDO-HEPATOLOGY: ERCP IMPLICATIONS IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Indications of ERCP

ERCP has become an essential tool for both diagnosing and treating conditions affecting the biliary and pancreatic ductal systems. The procedure involves advancing an endoscope into the duodenum, where the major and minor papillae are located and visually identified. Once access is achieved, the relevant ducts are cannulated and contrast is injected to outline the ductal anatomy[117]. ERCP offers a broad range of diagnostic capabilities, including direct visualization through cholangiopancreatoscopy, targeted tissue acquisition via biopsy or brush cytology, and evaluation of suspicious strictures or malignancies. On the therapeutic side, ERCP is routinely used for performing sphincterotomy, placing biliary or pancreatic stents, and removing ductal stones[118]. Clinically, ERCP is indicated for the evaluation and management of obstructive jaundice, pancreatic or biliary duct diseases, and unexplained pancreatitis. It also plays a role in diagnosing pancreatic cancer by enabling tissue sampling. Other indications include manometry in suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, nasobiliary drainage, treatment of biliary leaks or strictures, pseudocyst drainage, and dilation of the papilla or strictures within the ducts.

Endoscopic sphincterotomy, in particular, is reserved for cases where access to the ductal system is challenging, such as sphincter of Oddi dysfunction or stenosis, bile duct stones, biliary strictures, or bile sump syndrome following choledochoduodenostomy. It may also be considered in patients with ampullary carcinoma who are not suitable candidates for surgery[118,119].

Limitations of ERCP

ERCP is contraindicated in cases lacking evidence of pancreaticobiliary disease, when alternative, safer diagnostic modalities are available, or in patients presenting with nonspecific abdominal pain of unknown etiology[120]. Furthermore, ERCP should not be performed when its findings are unlikely to influence clinical management decisions[121]. Current expert consensus also advises against ERCP with sphincterotomy in patients classified under type III sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, given the absence of benefit and increased procedural risks in this subgroup[122].

Role of ERCP in cholestatic liver diseases

Cholestatic liver diseases encompass a broad spectrum of disorders involving intrahepatic, extrahepatic, or mixed bile duct pathology. These include both primary and secondary bile duct injuries, such as PSC, primary biliary cholangitis, and drug-induced liver injury[123].

PSC: PSC is a long-standing and gradually advancing cholestatic condition defined by multiple areas of narrowing that can affect any part of the biliary system, ranging from the smallest intrahepatic branches to the larger extrahepatic bile ducts[124]. Although the majority of cases exhibit combined intrahepatic and extrahepatic involvement, isolated intrahepatic or extrahepatic disease occurs in approximately 11% and 2% of patients, respectively[124]. MRCP is the preferred initial diagnostic modality due to its noninvasive nature and its ability to detect the characteristic “beaded” ductal appearance resulting from multifocal strictures alternating with intervening normal segments[124,125]. However, MRCP has limitations in detecting early or subtle intrahepatic disease and in distinguishing PSC from secondary sclerosing cholangitis. In these cases, ERCP retains a role as the gold standard for diagnosing early-stage PSC, especially when clinical suspicion remains high despite inconclusive MRCP findings[126]. In patients with dominant strictures, impaired biliary drainage and associated bacterial overgrowth increase the risk of proximal stone formation, symptomatic choledocholithiasis, and cholangitis. In such contexts, ERCP offers therapeutic advantages over MRCP, allowing for stricture dilation, stone extraction, and stent placement, thereby alleviating obstruction and preventing complications[124,126]. Patients with PSC are at markedly increased risk for developing cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), with estimates indicating a 400-fold lifetime risk. CCA is responsible for nearly one-third of mortality in PSC patients[127]. Despite this elevated risk, no consensus has been reached regarding optimal surveillance strategies for early detection of CCA. Major guidelines do not currently recommend routine ERCP with or without cytological brushing. The decision to proceed with ERCP should be individualized, based on clinical deterioration, biochemical changes, or ductal abnormalities on MRCP. When ERCP is performed, cytologic brushings with fluorescence in situ hybridization and biopsies should be obtained from all dominant strictures to evaluate for underlying malignancy[127].

IgG-4-related sclerosing cholangitis: Immunoglobulin G4-related sclerosing cholangitis (ISC) is characterized by concentric thickening of the bile duct walls and the formation of biliary strictures, culminating in chronic cholestasis[128]. ERCP may reveal multifocal strictures affecting the central bile ducts, often accompanied by mild proximal biliary dilatation despite the presence of long strictures. Additional radiologic hallmarks include circumferential bile duct wall thickening with preservation of the intraductal lumen, findings that are highly suggestive of ISC[129]. The mainstay of treatment for ISC is corticosteroid therapy. However, ERCP plays a crucial role in the diagnostic algorithm by facilitating tissue acquisition for histopathologic and immunohistochemical confirmation of immunoglobulin G4 infiltration. ERCP also enables endoscopic biliary drainage, which can provide symptomatic relief in patients with significant biliary obstruction[129].

Choledocholithiasis-associated cholestasis: ERCP remains the gold standard for the management of CBD stones; however, it is associated with a notable risk of adverse events, including post-ERCP pancreatitis, perforation, and bleeding, reported in approximately 6% to 15% of cases[118]. Comparative studies have demonstrated that EUS offers high diagnostic accuracy for CBD stones, with pooled sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value approximating 89.5%, 96.5%, 91.9%, and 95.3%, respectively[130]. These findings suggest that EUS can serve as an effective triage tool to avoid unnecessary ERCP procedures in patients with negative findings, thereby reducing the risk of procedure-related complications. Moreover, procedural duration is an important consideration, as ERCP interventions exceeding 40 minutes have been independently associated with increased rates of post-procedural complications, including prolonged hospitalization and pancreatitis[131]. In the context of acute cholangitis secondary to choledocholithiasis, current guidelines recommend early ERCP preferably within 24 hours as it has been shown to expedite clinical recovery, shorten the duration of antimicrobial therapy and hospital stay, and significantly lower morbidity and mortality rates[132].

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome-cholangiopathy and recurrent pyogenic cholangitis: Acquired immune deficiency syndrome-cholangiopathy represents a rare etiology of secondary sclerosing cholangitis, predominantly encountered in individuals with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection and severely depleted cluster of differentiation 4 counts (< 10 cells/mm3). The incidence of this condition has markedly declined over recent decades, mainly attributable to the widespread implementation and efficacy of antiretroviral therapy[125]. The disease typically manifests as distal CBD strictures in conjunction with papillary stenosis[125]. Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, on the other hand, is a distinct clinical entity most commonly observed in Southeast Asia. It is characterized by repeated biliary infections, frequently of bacterial origin, which lead to the development of intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary strictures, ductal scarring, and the subsequent formation of intraductal pigment stones[133]. Diagnostic ERCP typically reveals dilated intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts with relatively non-dilated peripheral ducts and multiple ductal stones features that help differentiate recurrent pyogenic cholangitis from PSC[133]. Therapeutically, ERCP remains the mainstay for the management of recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, particularly when the disease predominantly involves the extrahepatic biliary system, such as the CBD or common hepatic duct. Stone clearance via ERCP in such cases is associated with a high technical success rate of approximately 91.7%[133].

Post-liver transplant biliary stricture-related cholestasis: ABS is among the most frequent complications encountered following OLT, typically presenting with biochemical and clinical features of cholestasis[134]. The incidence of ABS is notably higher in recipients of living donor LT compared to those receiving grafts from deceased donors, with reported rates ranging from 10% to 37% vs 5% to 15%, respectively[134]. ERCP is the preferred initial therapeutic modality for managing post-OLT ABS. This typically involves endoscopic balloon dilation (EBD) followed by placement of plastic stents or fully covered self-expandable metallic stents[134]. EBD alone is associated with a higher recurrence rate compared to combination therapy with dilation and stenting (62% vs 31%)[135], underscoring the importance of a multimodal endoscopic approach in optimizing long-term outcomes.

Role of ERCP in pancreatic malignancies

ERCP remains a cornerstone in the diagnostic and therapeutic management of pancreatobiliary disorders. In patients with advanced or unresectable malignancies, palliation through biliary decompression is essential for symptom relief and improved quality of life[136]. According to current consensus guidelines, ERCP-guided biliary sampling is recommended when biliary decompression is concurrently indicated in cases of unresectable pancreatic masses. In contrast, for resectable lesions or when tissue acquisition via ERCP fails, EUS-guided FNB is preferred due to its superior diagnostic yield and safety profile[137]. With the growing diagnostic role of EUS in pancreatic cancer, especially in obtaining cytologic and histologic specimens for malignancy confirmation, the utility of ERCP has shifted predominantly toward therapeutic interventions[138]. While both techniques offer comparable diagnostic efficacy, EUS carries a significantly lower risk of procedure-related complications. ERCP-guided biliary drainage or decompression via transpapillary stenting remains the standard of care for managing biliary obstruction and its sequelae[139]. In patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, both endoscopic and surgical biliary drainage demonstrate comparable efficacy in symptom relief and long-term outcomes. However, ERCP offers a less invasive and safer approach compared to surgical bypass, particularly in individuals deemed poor surgical candidates[140]. Moreover, preoperative ERCP-guided biliary decompression is preferred in patients experiencing surgical delays due to neoadjuvant therapy planning or in those with severe malnutrition requiring nutritional optimization[141]. In unresectable cases, ERCP-guided transpapillary biliary stenting not only alleviates symptoms but is also associated with improved survival and reduced complication rates[141].

AI AND IMAGE ENHANCEMENT

Revolution of AI-assisted endoscopies

AI has rapidly evolved alongside advancements in information technology, offering significant potential to support clinical practice. In contrast to the variability introduced by human factors such as fatigue, inexperience, or stress, AI systems can maintain consistent performance. These tools help reduce diagnostic errors, support autonomous decision-making, and improve the overall efficiency and reliability of healthcare delivery[142].

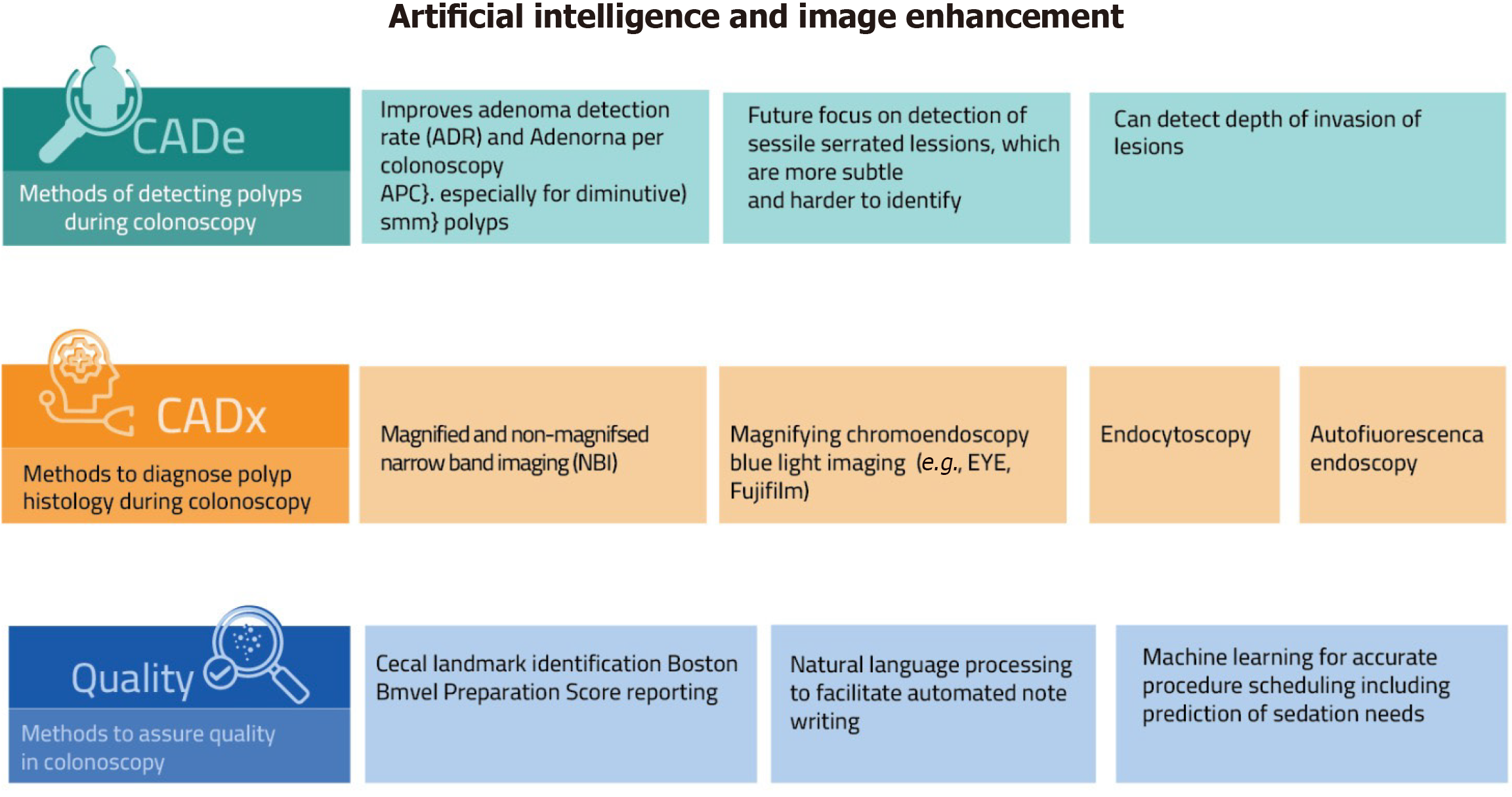

In gastrointestinal endoscopy, AI holds significant promise. It can minimize inter-operator variability, enhance diagnostic precision, and facilitate timely, evidence-based therapeutic decisions during procedures. Additionally, AI has the potential to reduce procedure time, cost, and endoscopist workload. Nonetheless, successful integration of AI into clinical practice necessitates the development and adherence to standardized guidelines[142]. AI systems in endoscopy are broadly categorized into computer-assisted detection, which supports lesion identification, and computer-assisted diagnosis, which assists in optical biopsy and lesion characterization. Beyond diagnostic support, these technologies are also finding their place in therapeutic endoscopy. For instance, they can help precisely outline lesion margins to guide complete and effective endoscopic resection. Additionally, computer-aided quality assurance tools are being developed to support standardization of procedural benchmarks and promote consistent, high-quality performance across endoscopists[142]. The various components and clinical applications of AI in colonoscopy are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Artificial intelligence and image enhancement in colonoscopy.

This figure illustrates the current and emerging applications of artificial intelligence and image enhancement technologies in colonoscopy. It highlights three main domains: Computer-aided detection for polyp identification, computer-aided diagnosis for real-time histologic assessment, and quality assurance tools to improve procedural outcomes. Examples include narrow band imaging, chromoendoscopy, endocytoscopy, and machine learning for procedure scheduling. CADe: Computer-aided detection; CADx: Computer-aided diagnosis; ADR: Adenoma detection rate; APC: Adenoma per colonoscopy; NBI: Narrow band imaging.

Image-enhanced endoscopies

Although white light imaging continues to serve as the backbone of diagnostic endoscopy, its ability to detect subtle mucosal changes remains limited. To address these shortcomings, image-enhanced endoscopy (IEE) has emerged as a transformative tool in gastrointestinal imaging. IEE techniques leverage a range of innovations from dye-based chromoendoscopy to digital image processing and customized light source modulation to sharpen visualization of mucosal and vascular architecture[143]. A notable leap forward in this domain is the introduction of the EVIS X1 platform by Olympus, which debuted in Europe and Japan in 2020. This system incorporates novel technologies such as texture and color enhancement imaging and red dichromatic imaging. The former improves the contrast of minute structural and color differences, aiding in early lesion detection, while the latter is designed to better visualize deep blood vessels and pinpoint bleeding sites.

When paired with real-time AI systems, these enhancements offer the potential to dramatically improve diagnostic accuracy and support earlier, more confident clinical decisions[143]. As technology evolves, the synergy between human expertise and machine precision is poised to redefine the future of endoscopic diagnostics.

Digital single-operator cholangioscopy and image-enhanced cholangioscopy

The introduction of digital single-operator cholangioscopy (D-SOC) is a significant advancement in biliary endoscopy, offering high-resolution imaging, simplified setup, and reduced logistical challenges that have expanded its diagnostic and therapeutic indications[144]. D-SOC is now used for evaluating indeterminate biliary strictures, enabling direct visualization and targeted tissue acquisition. It is particularly valuable for mapping the longitudinal extent of CCA, which ERCP may miss. In a recent study, D-SOC detected proximal and distal tumor spread undetected by ERCP in 20.0% and 11.6% of cases, respectively[144,145]. In addition, D-SOC facilitates the management of difficult CBD stones through intraductal electrohydraulic or laser lithotripsy, expanding the success rate beyond what is achievable with standard ERCP techniques such as sphincterotomy, sphincteroplasty, and basket or balloon extraction, which alone are effective in approximately 85% of cases[146]. Recent advances in image-enhancement technologies such as narrow band imaging (NBI) and i-scan have further refined the diagnostic yield of cholangioscopy. These modalities enhance mucosal and vascular patterns, aiding in the differentiation between benign and malignant intraductal lesions[147]. When applied during cholangioscopy, NBI provides superior contrast imaging that facilitates the endoscopic classification of intraductal lesions into papillary, polypoid, flat-elevated, granular, villous, or inflammatory types, surpassing the capabilities of conventional white-light imaging[148,149].