Published online Dec 14, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i46.112791

Revised: September 19, 2025

Accepted: October 30, 2025

Published online: December 14, 2025

Processing time: 126 Days and 17.4 Hours

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most prevalent malignant tumors worldwide and poses a significant threat to human health. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-negative early GC (HpN-EGC) often remains undetected because of its asymptomatic pro

To accurately and efficiently identify high-risk HpN-EGC individuals and guide clinical diagnosis and treatment, we developed a clinical prediction model for HpN-EGC.

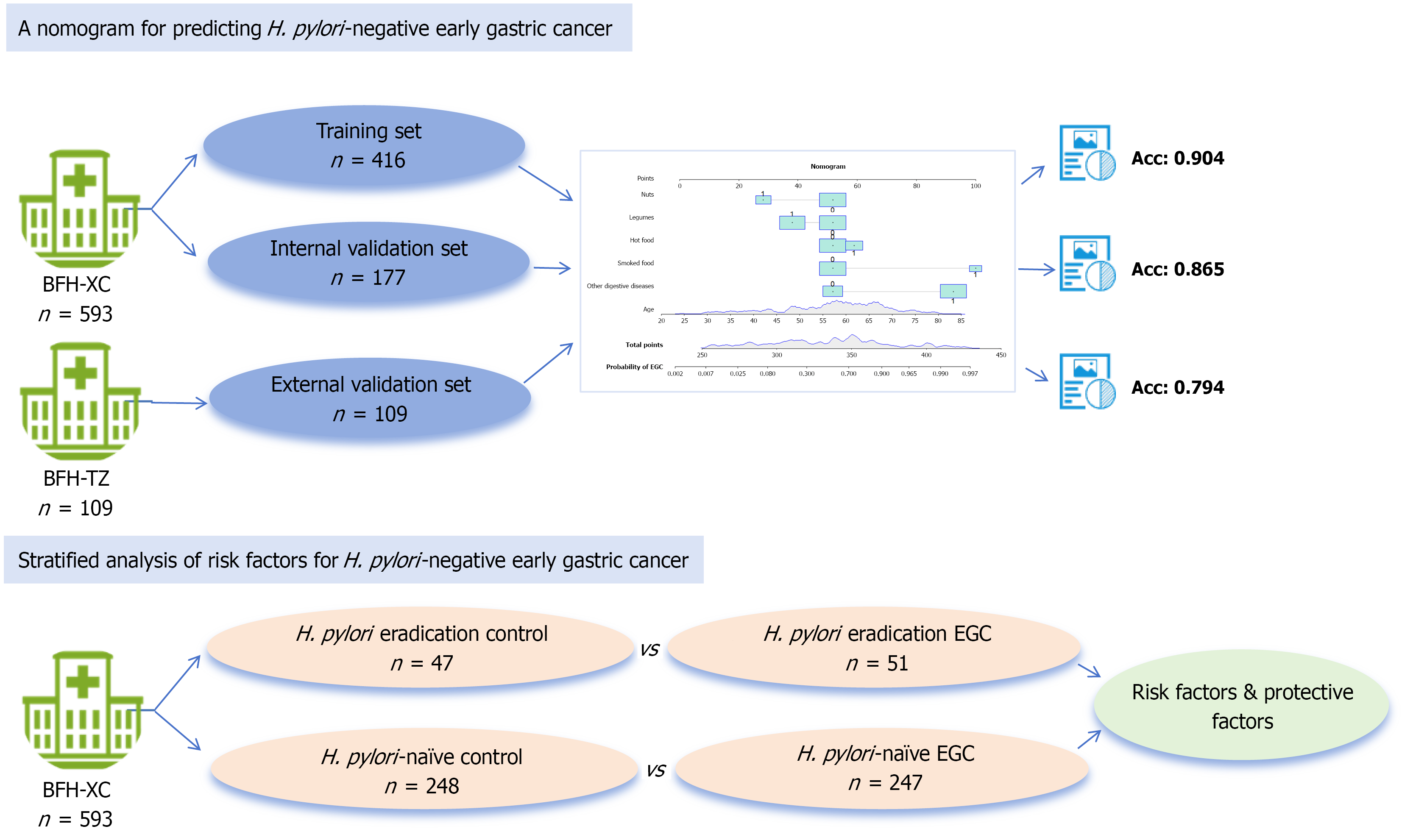

This retrospective case-control study evaluated 593 confirmed H. pylori-negative cases at a hospital. Eligible patients were randomized into training (n = 416) and internal validation (n = 177) groups. Multivariate logistic regression analysis identified significant predictors, which were incorporated into the nomogram. Patients from a different hospital were included in the external validation group (n = 109). Subgroup analyses explored H. pylori eradication (> 1 year) in H. pylori-naive populations.

Risk factors for HpN-EGC were advanced age [odds ratio (OR): 1.13], digestive comorbidities (OR: 17.55), and frequent consumption of smoked and hot foods (OR: 19.00; OR: 4.19). Regular legume and nut intake had protective effects (OR: 0.30; OR: 0.14). The nomogram showed excellent discrimination [training area under the curve (AUC) = 0.904; internal validation AUC = 0.865; external validation AUC = 0.794], stable calibration, and predictive accuracy, with a C-index of 0.904 (95% confi

The HpN-EGC risk prediction tool effectively identifies high-risk individuals based on age, digestive comorbi

Core Tip: Early gastric cancer (EGC), especially Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-negative EGC, often goes unnoticed because of the absence of obvious clinical symptoms in patients. Our study explored the risk and protective factors associated with the development of H. pylori-negative EGC, and established a risk prediction model. The model, established based on advanced age, digestive comorbidities, and the frequent consumption of smoked and hot foods, legumes and nuts, has superior accuracy and clinical application value.

- Citation: Liu XY, Wang YQ, Li P, Zhang ST, Sun XJ. Development and validation of a nomogram incorporating dietary factors for predicting Helicobacter pylori-negative early gastric cancer risk. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(46): 112791

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i46/112791.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i46.112791

Gastric cancer (GC) is a malignant tumor that poses a significant threat to human health. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 968000 cases of GC were diagnosed worldwide in 2022, ranking fifth in cancer incidence and deaths[1]. Early GC (EGC) is limited to the mucosal or submucosal layers regardless of the presence of lymph node metastasis[2]. Most EGC cases can be managed through endoscopic treatment, with a 5-year survival rate of up to 95%, whereas advanced GC has a 5-year survival rate of 30%-70% after surgical treatment[3,4]. Therefore, timely diagnosis and treatment of GC are important factors that affect its prognosis.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is a major risk factor for GC[5]. Although eradication of H. pylori could effectively reduce the risk of GC, tumors can develop even after eradication[6]. Some reports have indicated that H. pylori-negative GC accounts for 0.42%-5.4% of all GC cases[7]. A previous study based on the Japanese population that conducted patho

Currently, gastroscopy combined with a gastric mucosal biopsy is the most accurate method for diagnosing EGC. Other screening methods, including serological tests and imaging examinations, such as serum gastrin, gastrin 17, and upper gastrointestinal barium meal examinations, are limited by various factors, including high cost, invasive pro

Recently, nomograms have demonstrated great potential as risk assessment methods and are widely used as prog

To address this limitation, our study introduced a novel nomogram that advances the field in two key aspects. First, by integrating easily obtainable dietary factors as independent predictors, we obtained a more comprehensive view of the multifactorial etiology of EGC. Second, our tool delivered a non-invasive, cost-effective, and precise risk assessment specifically targeting the HpN-EGC sub-population. The study hopes to improve EGC detection rates and subsequently guide clinical decision-making.

A total of 874 patients who underwent gastroscopy and pathological examinations at the Beijing Friendship Hospital, Xicheng Campus between January 2018 and December 2021 were enrolled. A flow diagram of this study is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. The inclusion criteria for cases with HpN-EGC were as follows: (1) All patients aged ≥ 18 years; (2) Patients who underwent endoscopic submucosal dissection and postoperative pathological results confirmed EGC; and (3) Gastric biopsy, postoperative pathology, or the 13C-urea breath test confirmed negative results for H. pylori. The inclusion criteria cases without EGC were as follows: (1) All patients aged ≥ 18 years and agreed to undergo gastroscopy and pathological examination; (2) Pathological results revealed non-EGC; and (3) Gastric biopsy or the 13C-urea breath test confirmed negative results for H. pylori. Patients with a current H. pylori infection, H. pylori eradication within one year, severe comorbidities, mental illness, advanced GC, gastric stumps, metachronous GC, metastatic cancer, or incom

Following the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 593 eligible participants were enrolled in the study. The patients were randomly allocated in a 7:3 ratio between the training and internal validation datasets. The training set included 209 post-endoscopic submucosal dissection patients with EGC in the HpN-EGC group, and 207 patients with histologically confirmed non-EGC diagnoses in the HpN-control group. Additionally, 109 patients enrolled at the Beijing Friendship Hospital, Tongzhou Campus between March and December 2022 constituted the external validation cohort.

Patients with HpN-EGC were stratified into two groups: The H. pylori eradication EGC group, comprising patients who had successfully completed H. pylori eradication therapy more than 1 year prior, and the H. pylori-naive EGC group, comprising patients with no history of H. pylori infection. The 1-year interval following eradication therapy was estab

General information (age, sex, body mass index, and educational level) and lifestyle habits, including smoking, drinking, and dietary habits (hard, fried, spicy, smoked, hot, and moldy foods, as well as onion and garlic, legumes, nuts, coarse grains, etc.), were collected. “Frequent” consumption was defined as a dietary intake frequency of ≥ 3 times per week with a serving size of ≥ 50 g; otherwise, it was defined as “occasional”. The threshold setting of ≥ 3 times per week was established with reference to previous literature and was further refined based on the content of the food frequency questionnaire[19]. The threshold setting of > 50 g for dietary quality was based on the common options used in the simplified Food Frequency Questionnaire developed by Gao et al[20], which aimed to avoid significant deviations in both the frequency and quantity of patients’ dietary intake. Additionally, the nut intake threshold was slightly adjusted to 28 g/week[21].

Clinical symptoms (including dysphagia, acid reflux, heartburn, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, hematemesis, melena, marasmus, fatigue, and anemia) and a family history of cancer were also recorded. In addition, we investigated whether the patients had comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiac and cerebral diseases (including cerebral hemorrhage, cerebral infarction, and cerebral vascular stenosis), and digestive comorbidities [including chronic atrophic gastritis, gastric ulcers, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)]. The Charlson comor

Statistical analysis of data and construction of the nomogram were performed using SPSS (26.0) and R (4.4.1). Continuous variables following a normal distribution were presented as mean ± SD and compared using Student’s t-test, whereas non-normally distributed variables were expressed as median (interquartile range) and analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. The assumption of linearity for the continuous variable “age” was assessed using restricted cubic splines with 4 knots. A likelihood ratio test showed no significant departure from linearity (P = 0.53); the spline curve is included in Supplementary Figure 2. Therefore, age was entered into the final model as a linear term. Categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Logistic regression analysis (forward: Likelihood ratio method) was conducted to explore the risk factors associated with EGC. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The nomogram was established using “rms”, “regplot”, and “DynNom” packages. A bootstrap test was conducted to validate the model. The model prediction efficacy was tested using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the curve (AUC). The effectiveness and clinical application of the model were further validated using calibration curve, decision curve analysis, and clinical impact curve.

A total of 874 patients who underwent gastroscopy and pathological examinations agreed to participate in this study. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 593 patients were included in the study, with 416 and 177 patients in the training and internal validation sets, respectively (Figure 1). The clinical characteristics of the HpN-EGC and HpN-control groups are summarized in Table 1. Sex, age, smoking, drinking, and educational level were significantly different be

| HpN-control group (n = 207) | HpN-EGC group (n = 209) | P value | |

| Sex | < 0.001 | ||

| Male | 80 (38.6) | 136 (65.1) | |

| Female | 127 (61.4) | 73 (34.9) | |

| Age, years | 53.0 (42.0, 61.0) | 63.0 (57.0, 68.0) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.0 (21.8, 26.3) | 23.7 (21.5, 25.9) | 0.499 |

| Smoking1 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 21 (10.1) | 101 (48.3) | |

| No | 186 (89.9) | 108 (51.7) | |

| Drinking1 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 33 (15.9) | 88 (42.1) | |

| No | 174 (84.1) | 121 (57.9) | |

| Educational level | < 0.001 | ||

| High school or above | 178 (86.0) | 127 (60.8) | |

| Below high school | 29 (14.0) | 82 (39.2) | |

| Clinical symptoms | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 130 (62.8) | 163 (78.0) | |

| No | 77 (37.2) | 46 (22.0) | |

| Hypertension | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 38 (18.4) | 77 (36.8) | |

| No | 169 (81.6) | 132 (63.2) | |

| Diabetes | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 9 (4.3) | 37 (17.7) | |

| No | 198 (95.7) | 172 (82.3) | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.626 | ||

| Yes | 32 (15.5) | 36 (17.2) | |

| No | 175 (84.5) | 173 (82.8) | |

| Cardiac and cerebral diseases | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 12 (5.8) | 50 (23.9) | |

| No | 195 (94.2) | 159 (76.1) | |

| Digestive comorbidities | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 83 (40.1) | 179 (85.6) | |

| No | 124 (59.9) | 30 (14.4) | |

| Family history of tumors | 0.214 | ||

| Yes | 53 (25.6) | 65 (31.1) | |

| No | 154 (74.4) | 144 (68.9) | |

| CCI | 0.39 ± 0.70 | 0.92 ± 1.11 | < 0.001 |

| Aspirin2 | 0.365 | ||

| Yes | 6 (7.9) | 14 (12.0) | |

| No | 70 (92.1) | 103 (88.0) | |

| Clopidogrel2 | 0.170 | ||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 5 (4.3) | |

| No | 76 (100.0) | 111 (95.7) | |

| Metformin2 | 0.003 | ||

| Yes | 1 (1.3) | 16 (13.8) | |

| No | 75 (98.7) | 100 (86.2) | |

| Corticosteroids2 | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 1 (1.3) | 2 (1.7) | |

| No | 75 (98.7) | 115 (98.3) | |

| PPI2 | 0.020 | ||

| Yes | 10 (4.8) | 23 (11.0) | |

| No | 197 (95.2) | 186 (89.0) | |

| Hard food | < 0.001 | ||

| Occasional | 204 (98.6) | 166 (79.4) | |

| Frequent | 3 (1.4) | 43 (20.6) | |

| Fried food | 0.055 | ||

| Occasional | 192 (92.8) | 182 (87.1) | |

| Frequent | 15 (7.2) | 27 (12.9) | |

| Spicy food | < 0.001 | ||

| Occasional | 189 (91.3) | 155 (74.2) | |

| Frequent | 18 (8.7) | 54 (25.8) | |

| Smoked food | < 0.001 | ||

| Occasional | 200 (96.6) | 142 (67.9) | |

| Frequent | 7 (3.4) | 67 (32.1) | |

| Hot food | 0.013 | ||

| Occasional | 156 (75.4) | 134 (64.1) | |

| Frequent | 51 (24.6) | 75 (35.9) | |

| Moldy food | 1.000 | ||

| Occasional | 207 (100.0) | 208 (99.5) | |

| Frequent | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Onion and garlic | 0.005 | ||

| Occasional | 46 (22.2) | 25 (12.0) | |

| Frequent | 161 (77.8) | 184 (88.0) | |

| Legumes | < 0.001 | ||

| Occasional | 81 (39.1) | 134 (64.1) | |

| Frequent | 126 (60.9) | 75 (35.9) | |

| Nuts | < 0.001 | ||

| Occasional | 138 (66.7) | 174 (83.3) | |

| Frequent | 69 (33.3) | 35 (16.7) | |

| Coarse grains | 0.522 | ||

| Occasional | 135 (65.2) | 130 (62.2) | |

| Frequent | 72 (34.8) | 79 (37.8) | |

| Meat, egg, and milk | 0.617 | ||

| Occasional | 16 (7.7) | 19 (9.1) | |

| Frequent | 191 (92.3) | 190 (90.9) | |

| Fruits and vegetables | 0.988 | ||

| Occasional | 5 (2.4) | 4 (1.9) | |

| Frequent | 202 (97.6) | 205 (98.1) |

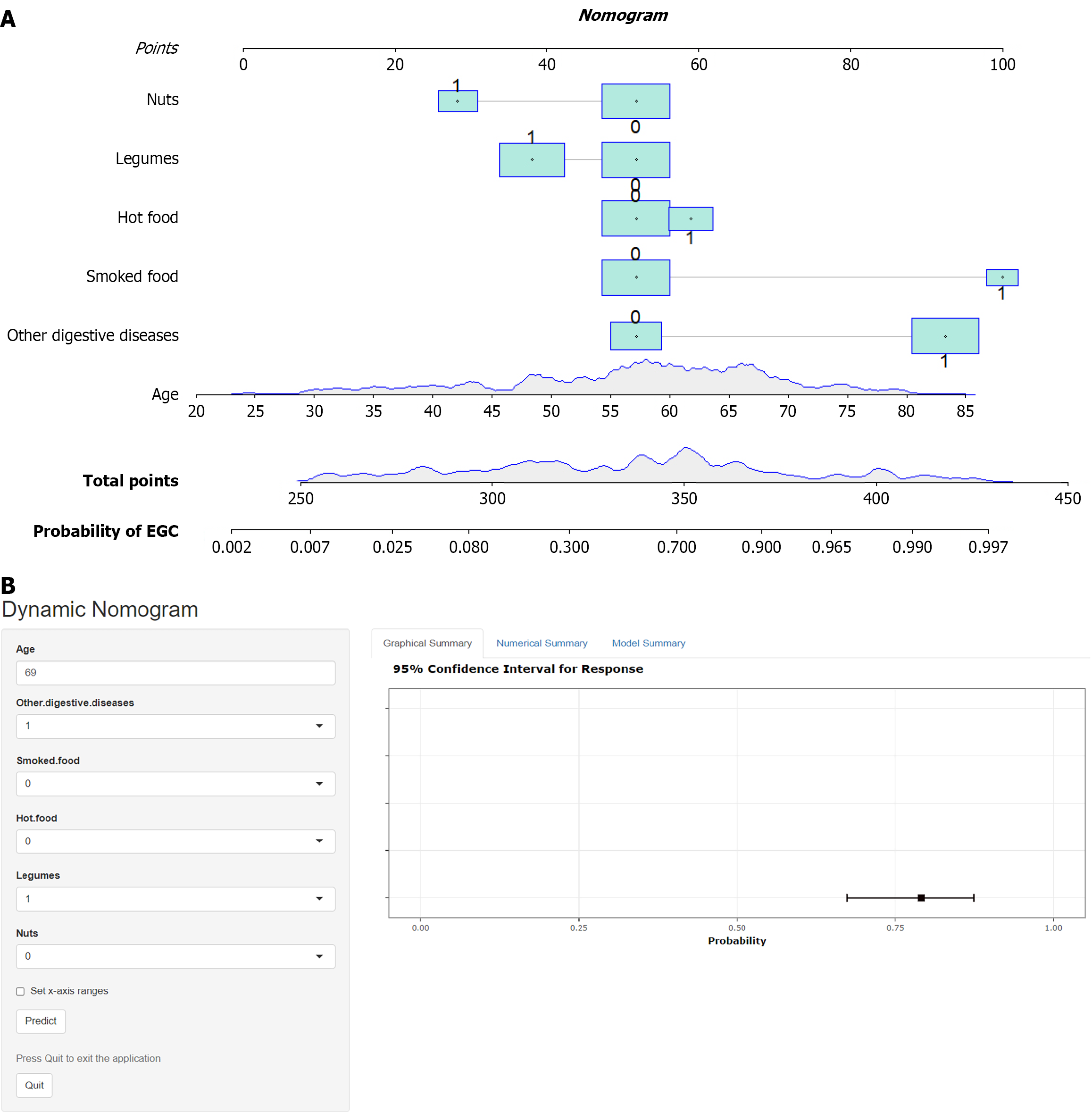

Features with statistically significant differences were included in univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. The results demonstrated that age, digestive comorbidities, smoked and hot foods, legumes, and nuts were associated with the development of HpN-EGC (Table 2). Advanced age [odds ratio (OR): 1.13, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.05-1.22], digestive comorbidities (OR: 17.55, 95%CI: 4.36-96.25), and frequent consumption of smoked and hot foods (OR: 19.00, 95%CI: 1.75-45.38; OR: 4.19, 95%CI: 1.10-18.41) were independent risk factors for HpN-EGC, whereas legumes and nuts intake (OR: 0.30, 95%CI: 0.09-0.89; OR: 0.14, 95%CI: 0.037-0.48) served as protective factors. Furthermore, bootstrap validation analyses for the significant factors were conducted, with the results shown in Supplementary Table 2. Addi

| Characteristics | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Sex | 0.34 | 0.23-0.50 | < 0.001 | 0.55 | 0.12-2.54 | 0.446 |

| Female vs male | ||||||

| Age, years | 1.11 | 1.08-1.13 | < 0.001 | 1.13 | 1.05-1.22 | 0.001 |

| Smoking1 | 8.28 | 4.98-14.33 | < 0.001 | 3.79 | 0.74-21.96 | 0.119 |

| Yes vs no | ||||||

| Drinking1 | 3.83 | 2.44-6.15 | < 0.001 | 2.23 | 0.47-10.60 | 0.308 |

| Yes vs no | ||||||

| Educational level | 0.25 | 0.15-0.40 | < 0.001 | 0.55 | 0.15-1.87 | 0.342 |

| Above vs below high school | ||||||

| Clinical symptoms | 2.10 | 1.37-3.25 | < 0.001 | 1.76 | 0.53-6.12 | 0.359 |

| Yes vs no | ||||||

| Hypertension | 2.59 | 1.66-4.10 | < 0.001 | 0.98 | 0.30-3.10 | 0.971 |

| Yes vs no | ||||||

| Diabetes | 4.73 | 2.32-10.70 | < 0.001 | 1.93 | 0.35-11.82 | 0.456 |

| Yes vs no | ||||||

| Cardiac and cerebral diseases | 5.11 | 2.72-10.36 | < 0.001 | 3.87 | 0.93-18.24 | 0.070 |

| Yes vs no | ||||||

| Digestive comorbidities | 8.91 | 5.60-14.55 | < 0.001 | 17.55 | 4.36-96.25 | < 0.001 |

| Yes vs no | ||||||

| CCI | 1.94 | 1.53-2.50 | < 0.001 | 1.36 | 0.70-2.86 | 0.386 |

| Metformin2 | 12.00 | 2.37-218.98 | 0.017 | 1.60 | 0.07-76.8 | 0.778 |

| Yes vs no | ||||||

| PPI2 | 2.24 | 1.16-5.48 | 0.023 | 2.26 | 0.47-11.79 | 0.317 |

| Yes vs no | ||||||

| Hard food | 17.61 | 6.28-73.58 | < 0.001 | 17.97 | 0.24-205.54 | 0.992 |

| Frequent vs occasional | ||||||

| Spicy food | 3.66 | 2.10-6.65 | < 0.001 | 1.14 | 0.24-6.05 | 0.872 |

| Frequent vs occasional | ||||||

| Smoked food | 13.48 | 6.42-33.06 | < 0.001 | 19.00 | 1.75-453.77 | 0.035 |

| Frequent vs occasional | ||||||

| Hot food | 1.71 | 1.12-2.63 | 0.013 | 4.19 | 1.10-18.41 | 0.043 |

| Frequent vs occasional | ||||||

| Onion and garlic | 2.10 | 1.25-3.62 | 0.006 | 4.31 | 0.95-23.22 | 0.068 |

| Frequent vs occasional | ||||||

| Legumes | 0.36 | 0.24-0.53 | < 0.001 | 0.30 | 0.09-0.89 | 0.033 |

| Frequent vs occasional | ||||||

| Nuts | 0.40 | 0.25-0.64 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.037-0.48 | 0.003 |

| Frequent vs occasional | ||||||

Based on the results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis, six independent influencing factors (age, digestive comorbidities, smoked foods, hot foods, legumes, and nuts) were included in the risk prediction model. The assignments of the variables included in the model are presented in Supplementary Table 3. A nomogram was created to visualize the prediction model. Numerous variables included in the nomogram were incorporated to obtain total scores and, corres

This nomogram serves as a clinical decision-support tool without invasive examinations and is specifically designed for HpN adult patients, enabling the quantitative assessment of HpN-EGC risk stratification. This model incorporates multiple risk and protective factors to generate individualized risk profiles, and gastroscopic examination is strongly recommended for patients with elevated risk scores. To illustrate the clinical application of our risk assessment model, we presented a representative case in the online dynamic nomogram accessible at https://predictrt.shinyapps.io/DynNo

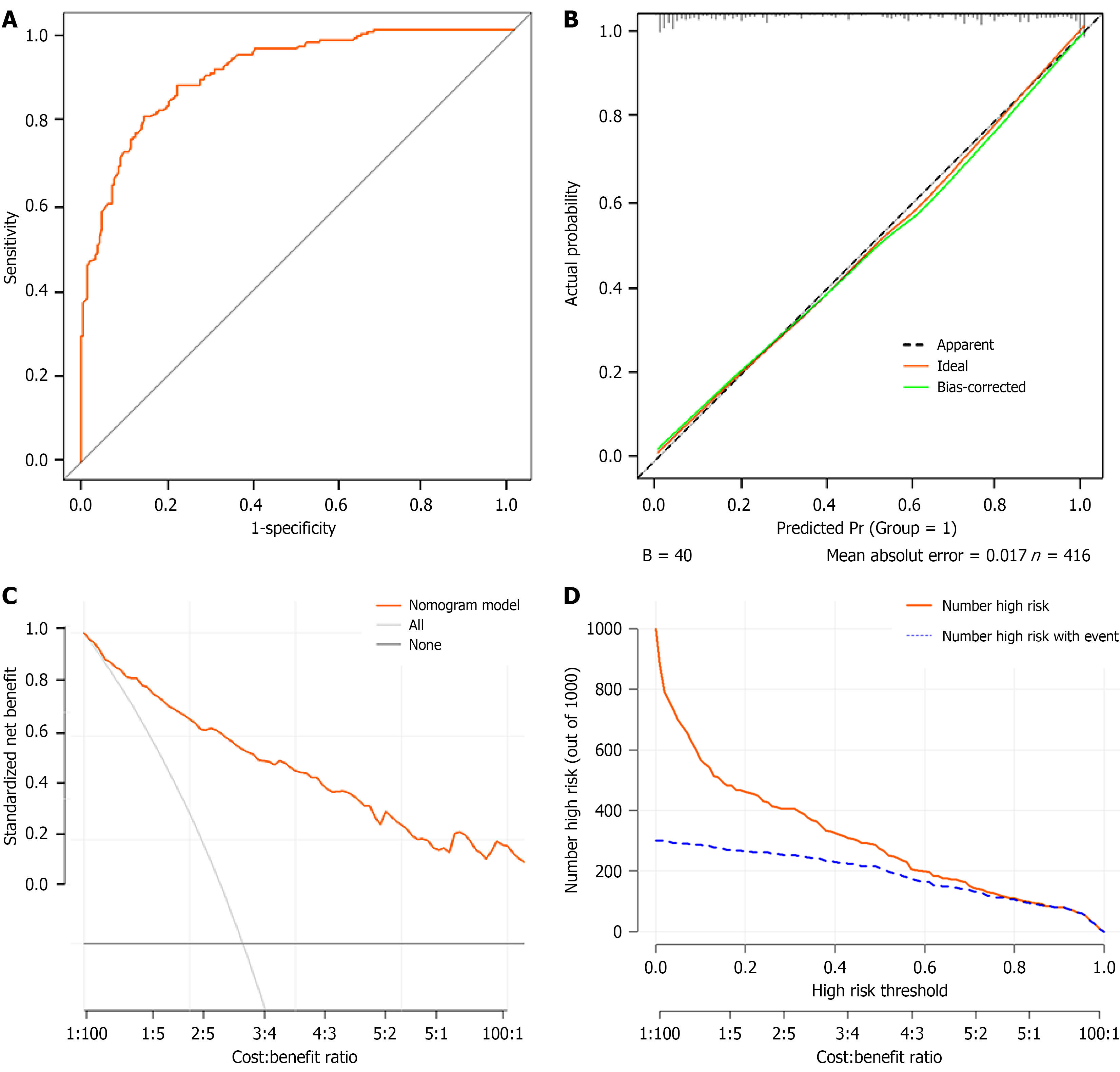

The C-index of the nomogram was 0.904 (95%CI: 0.876-0.931) and the AUC was 0.904 (Figure 3A), indicating that the nomogram had good discriminatory ability and predictive accuracy. The prediction curve of the model closely aligned with the actual calibration curve (Figure 3B). The Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 statistic was 7.57 with a P value of 0.477, indi

Additionally, we refitted the model by replacing the composite “digestive comorbidity” variable with separate indi

Patients with HpN-EGC were further categorized into those who had successfully undergone H. pylori eradication

| Characteristics | H. pylori eradication control group, n = 47 | H. pylori eradication EGC group, n = 51 | P value | H. pylori-naive control group, | H. pylori-naive EGC group, n = 247 | P value |

| Sex | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Male | 17 (36.2) | 39 (76.5) | 96 (38.7) | 169 (68.4) | ||

| Female | 30 (63.8) | 12 (23.5) | 152 (61.3) | 78 (31.6) | ||

| Age, years | 46.23 ± 11.27 | 62.41 ± 8.31 | < 0.001 | 52.71 ± 12.49 | 63.85 ± 8.73 | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.74 ± 3.81 | 23.21 ± 2.78 | 0.432 | 24.34 ± 3.62 | 24.03 ± 3.58 | 0.339 |

| Smoking1 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 7 (14.9) | 30 (58.8) | 24 (9.7) | 125 (50.6) | ||

| No | 40 (85.1) | 21 (41.2) | 224 (90.3) | 122 (49.4) | ||

| Drinking1 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 6 (12.8) | 27 (52.9) | 43 (17.3) | 106 (42.9) | ||

| No | 41 (87.2) | 24 (47.1) | 205 (82.7) | 141 (57.1) | ||

| Educational level | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| High school or above | 45 (95.7) | 31 (60.8) | 209 (95.7) | 146 (59.1) | ||

| Below high school | 2 (4.3) | 20 (39.2) | 39 (4.3) | 101 (40.9) | ||

| Clinical symptoms | < 0.001 | 0.032 | ||||

| Yes | 20 (42.6) | 45 (88.2) | 165 (66.5) | 186 (75.3) | ||

| No | 27 (57.4) | 6 (11.8) | 83 (33.5) | 61 (24.7) | ||

| Hypertension | 0.099 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 8 (17.0) | 35 (68.6) | 47 (19.0) | 98 (39.7) | ||

| No | 39 (83.0) | 16 (31.4) | 201 (81.0) | 149 (60.3) | ||

| Diabetes | 0.114 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 1 (2.1) | 6 (11.8) | 11 (4.4) | 49 (19.8) | ||

| No | 46 (97.9) | 45 (88.2) | 237 (95.6) | 198 (80.2) | ||

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.889 | 0.984 | ||||

| Yes | 6 (12.8) | 7 (13.7) | 41 (16.5) | 41 (16.6) | ||

| No | 41 (87.2) | 44 (86.3) | 207 (83.5) | 206 (83.4) | ||

| Cardiac and cerebral diseases | 0.094 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 2 (4.3) | 8 (15.7) | 10 (4.0) | 67 (27.1) | ||

| No | 45 (95.7) | 43 (84.3) | 238 (96.0) | 180 (72.9) | ||

| Digestive comorbidities | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 17 (36.2) | 44 (86.3) | 106 (42.7) | 181 (73.3) | ||

| No | 30 (63.8) | 7 (13.7) | 142 (57.3) | 66 (26.7) | ||

| Family history of GC | 0.830 | 0.156 | ||||

| Yes | 12 (25.5) | 14 (27.5) | 64 (25.8) | 169 (68.4) | ||

| No | 35 (74.5) | 37 (72.8) | 184 (74.2) | 78 (31.6) | ||

| CCI | 0.40 ± 0.68 | 0.90 ± 1.17 | 0.014 | 0.38 ± 0.73 | 0.95 ± 1.08 | < 0.001 |

| Aspirin2 | 0.672 | 0.015 | ||||

| Yes | 3 (23.1) | 4 (16.0) | 4 (4.4) | 21 (14.4) | ||

| No | 10 (76.9) | 21 (84.0) | 87 (95.6) | 125 (85.6) | ||

| Metformin2 | 0.538 | 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.0) | 1 (1.1) | 19 (13.1) | ||

| No | 13 (100.0) | 23 (92.0) | 90 (98.9) | 126 (86.9) | ||

| Corticosteroids2 | 0.342 | 0.301 | ||||

| Yes | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.7) | ||

| No | 12 (92.3) | 25 (100.0) | 91 (100.0) | 142 (97.3) | ||

| PPI2 | 0.094 | 0.129 | ||||

| Yes | 45 (95.7) | 43 (84.3) | 11 (4.4) | 228 (92.3) | ||

| No | 2 (4.3) | 8 (15.7) | 237 (95.6) | 19 (7.7) | ||

| Hard food | 0.057 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Occasional | 47 (100.0) | 46 (90.2) | 244 (98.4) | 204 (82.6) | ||

| Frequent | 0 (0.0) | 5 (9.8) | 4 (1.6) | 43 (17.4) | ||

| Fried food | 0.025 | 0.066 | ||||

| Occasional | 37 (78.7) | 48 (94.1) | 230 (92.7) | 217 (87.9) | ||

| Frequent | 10 (21.3) | 3 (5.9) | 18 (7.3) | 30 (12.1) | ||

| Spicy food | 0.111 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Occasional | 41 (87.2) | 38 (74.5) | 225 (90.7) | 195 (78.9) | ||

| Frequent | 6 (12.8) | 13 (25.5) | 23 (9.3) | 52 (21.1) | ||

| Smoked food | 0.019 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Occasional | 44 (93.6) | 39 (76.5) | 240 (96.8) | 177 (71.7) | ||

| Frequent | 3 (6.4) | 12 (23.5) | 8 (3.2) | 70 (28.3) | ||

| Hot food | 0.047 | 0.037 | ||||

| Occasional | 38 (80.9) | 32 (62.7) | 184 (74.2) | 162 (65.6) | ||

| Frequent | 9 (19.1) | 19 (37.3) | 64 (25.8) | 85 (34.4) | ||

| Onion and garlic | 0.475 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Occasional | 10 (21.3) | 8 (15.7) | 61 (24.6) | 28 (11.3) | ||

| Frequent | 37 (78.7) | 43 (84.3) | 187 (75.4) | 219 (88.7) | ||

| Legumes | 0.002 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Occasional | 16 (34.0) | 33 (64.7) | 99 (39.9) | 161 (65.4) | ||

| Frequent | 31 (66.0) | 18 (35.3) | 149 (60.1) | 85 (34.6) | ||

| Nuts | 0.035 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Occasional | 31 (66.0 | 43 (84.3) | 176 (71.0) | 212 (85.8) | ||

| Frequent | 16 (34.0) | 8 (15.7) | 72 (29.0) | 35 (14.2) | ||

| Coarse grains | 0.756 | 0.177 | ||||

| Occasional | 30 (63.8) | 31 (60.8) | 168 (67.7) | 153 (61.9) | ||

| Frequent | 17 (36.2) | 20 (39.2) | 80 (32.3) | 94 (38.1) | ||

| Meat, egg, and milk | 0.679 | 0.510 | ||||

| Occasional | 2 (4.3) | 4 (7.8) | 19 (7.7) | 23 (9.3) | ||

| Frequent | 45 (95.7) | 47 (92.2) | 229 (92.3) | 224 (90.7) | ||

| Fruits and vegetables | 0.496 | 0.724 | ||||

| Occasional | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.9) | 5 (2.0) | 3 (1.2) | ||

| Frequent | 47 (100.0) | 49 (96.1) | 243 (98.0) | 244 (98.8) |

| H. pylori eradication EGC | H. pylori-naive EGC | H. pylori infection EGC | |||||||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age, years | 1.20 | 1.05-1.37 | 0.008 | 1.13 | 1.06-1.19 | < 0.001 | 1.12 | 1.02-1.22 | 0.014 |

| Smoking | 15.84 | 0.75-334.67 | 0.076 | 5.70 | 1.42-22.96 | 0.014 | 8.29 | 0.34-201.66 | 0.194 |

| Yes vs no | |||||||||

| Drinking | 2.82 | 0.17-47.58 | 0.473 | 3.98 | 1.02-15.59 | 0.047 | 12.9 | 1.42-117.8 | 0.023 |

| Yes vs no | |||||||||

| Digestive comorbidities | 3.57 | 0.35-36.60 | 0.284 | 5.32 | 1.57-18.03 | 0.003 | 6.63 | 1.02-43.34 | 0.048 |

| Yes vs no | |||||||||

| Smoked food | 8.78 | 0.29-267.44 | 0.213 | 9.97 | 1.54-64.67 | 0.016 | |||

| Frequent vs occasional | |||||||||

| Hot food | 11.28 | 0.70-182.98 | 0.088 | 3.59 | 1.07-12.11 | 0.039 | |||

| Frequent vs occasional | |||||||||

| Onion and garlic | 5.26 | 1.21-22.88 | 0.027 | 3.67 | 0.54-25.08 | 0.186 | |||

| Frequent vs occasional | |||||||||

| Legumes | 0.08 | 0.01-0.72 | 0.028 | 0.17 | 0.06-0.51 | 0.002 | 0.14 | 0.02-0.96 | 0.045 |

| Frequent vs occasional | |||||||||

| Nuts | 0.04 | 0.01-0.55 | 0.017 | 0.24 | 0.08-0.77 | 0.015 | 0.11 | 0.02-0.86 | 0.035 |

| Frequent vs occasional | |||||||||

To ensure a comprehensive assessment of EGC risk factors, we extended our analysis to include H. pylori-infected patients from previously excluded cases; the detailed results are presented in Supplementary Table 5. Notably, advanced age and alcohol consumption emerged as significant risk factors for EGC in H. pylori-infected patients, whereas the die

GC is a severe disease influenced by genetic and environmental factors, and therapeutic effects and prognosis are closely related to the timing of diagnosis and treatment[23]. However, most patients with EGC experience delayed diagnosis and treatment due to the absence of clinical symptoms or specific signs. Several studies have elucidated the characteristics and pathogenesis of GC related to H. pylori infection; however, studies on HpN-EGC were limited. This study explored the risk factors related to HpN-EGC and established a nomogram for the initial stratification of patients.

The results demonstrated that age, digestive comorbidities, the dietary habits of smoked food, hot food, legumes, and nuts were associated with the development of HpN-EGC. Digestive comorbidities, specifically chronic atrophic gastritis, gastric ulcers, and GERD, were associated with the risk of HpN-EGC and incorporated them into the prediction model. In addition, an alternative model was developed by replacing the composite “digestive comorbidity” variables with sepa

The pathological features of chronic atrophic gastritis include reduction or loss of gastric glands accompanied by inflammatory infiltration, often indicating a significantly increased risk of GC[24]. In a pooled analysis of 11 case-control studies, researchers discovered a positive association between gastric ulcers and GC risk; however, no association was noted between duodenal ulcers and GC risk[25]. One study reported that patients with GERD had a two-four times higher risk of GC, possibly because of intestinal metaplasia of the cardia[26,27].

This study indicated that frequent consumption of smoked and hot foods was an independent risk factor for HpN-EGC, whereas frequent consumption of legumes and nuts was an independent protective factor for HpN-EGC. The World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research concluded that smoked foods may be a primary cause of GC because they contain many carcinogens, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and N-nitroso com

Wang et al[32] discovered that soybean intake significantly decreased the risk of GC by 36%, suggesting that legumes are protective against GC, which is consistent with the results of our study. This may be attributed to the numerous bene

Previous studies have suggested that aging is an important risk factor for GC, and its incidence gradually increases with age[36]. In the subgroup analysis, the incidence of EGC in older patients was significantly elevated, which is consis

In the subgroup analysis, we found that the association between smoking and alcohol consumption was confined to the H. pylori-naive population, suggesting that H. pylori-naive individuals should be encouraged to quit smoking and limit alcohol consumption. However, a study by Kim et al[10] found no statistically significant differences in smoking and alcohol consumption between resectable HpN and H. pylori-positive GC patients[10]. Consequently, future studies with larger sample sizes are required to elucidate the association between tobacco and alcohol use and H. pylori-naive EGC. Additionally, individuals without H. pylori infection should focus on maintaining a healthy diet. Compared to the H. py

The prediction model for HpN-EGC had effective discriminatory ability, superior predictive accuracy, and good clinical application value, thereby assisting in clinical decision-making. A previous study developed a GC risk prediction rule comprising seven variables (age, sex, pepsinogen I/II ratio, gastrin-17 level, H. pylori infection, pickled food, and fried food) with an AUC of 0.757 but without visualization[37]. Compared to the established model, our nomogram de

Our study has several limitations. First, the nomogram was developed using a single-center cohort, which may limit its generalizability because of a potential selection bias. Furthermore, the inclusion criteria, particularly the requirement for complete dietary data, may have resulted in a specific patient subpopulation, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings. Most notably, because dietary factors were integral to our model, significant regional and cultural variations could influence the external validity of the model when applied to populations with distinct dietary habits. Multi-center prospective studies across diverse geographical regions are essential to externally validate and potentially recalibrate our model. Second, the use of a Food Frequency Questionnaire is susceptible to recall bias and measurement errors when assessing dietary habits. Although this questionnaire is a widely used and validated tool, future studies may benefit from more objective dietary assessment methods. Third, our model focused on clinical and epidemiological variables and did not incorporate genetic factors that are known to play a role in gastric carcinogenesis. Integrating genetic markers could further enhance the model performance in the future. Although the model demonstrated good discriminative ability, we observed exceptionally high ORs for “digestive comorbidities” and “smoked foods”. While bootstrap validation suggests that these estimates are relatively statistically stable, their considerable magnitude may be influenced by relatively small subgroup sample sizes, unmeasured confounding factors, or over-optimism due to potential model overfitting. Therefore, these specific associations must be interpreted with extreme caution, and their exact risks require further validation in prospective cohort studies or studies with larger sample sizes. Moreover, owing to the limited sample size of the H. pylori eradication group, we were unable to perform a refined stratified analysis of the nomogram. Thus, the conclusions derived from this subgroup analysis should be considered merely exploratory findings and require further validation in future studies. External validation was performed using a relatively small sample size (n = 109), which may have affected the stability of the performance metrics and necessitated further validation in larger cohorts.

Our risk-prediction tool for HpN-EGC effectively identified high-risk individuals by leveraging six readily available clinical parameters: Age, digestive comorbidities, and consumption of smoked and hot foods, legumes, and nuts. Furthermore, the stratified analysis revealed distinct risk and protective factors across various population subgroups.

| 1. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 12562] [Article Influence: 6281.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 2. | Shitara K, Chin K, Yoshikawa T, Katai H, Terashima M, Ito S, Hirao M, Yoshida K, Oki E, Sasako M, Emi Y, Tsujinaka T. Phase II study of adjuvant chemotherapy of S-1 plus oxaliplatin for patients with stage III gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:175-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liang W, Huang J, Song L, Cui H, Yuan Z, Chen R, Zhang P, Zhang Q, Wang N, Cui J, Wei B. Five-year long-term comparison of robotic and laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a large single-center cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:6333-6342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Katai H, Ishikawa T, Akazawa K, Isobe Y, Miyashiro I, Oda I, Tsujitani S, Ono H, Tanabe S, Fukagawa T, Nunobe S, Kakeji Y, Nashimoto A; Registration Committee of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Five-year survival analysis of surgically resected gastric cancer cases in Japan: a retrospective analysis of more than 100,000 patients from the nationwide registry of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (2001-2007). Gastric Cancer. 2018;21:144-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 377] [Article Influence: 47.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fischbach W, Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter Pylori Infection. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:429-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Fukase K, Kato M, Kikuchi S, Inoue K, Uemura N, Okamoto S, Terao S, Amagai K, Hayashi S, Asaka M; Japan Gast Study Group. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:392-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 876] [Cited by in RCA: 952] [Article Influence: 52.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yamamoto Y, Fujisaki J, Omae M, Hirasawa T, Igarashi M. Helicobacter pylori-negative gastric cancer: characteristics and endoscopic findings. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:551-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Enomoto H, Watanabe H, Nishikura K, Umezawa H, Asakura H. Topographic distribution of Helicobacter pylori in the resected stomach. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:473-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yoon H, Kim N, Lee HS, Shin CM, Park YS, Lee DH, Jung HC, Song IS. Helicobacter pylori-negative gastric cancer in South Korea: incidence and clinicopathologic characteristics. Helicobacter. 2011;16:382-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kim HJ, Kim N, Yoon H, Choi YJ, Lee JY, Kwon YH, Yoon K, Jo HJ, Shin CM, Park YS, Park DJ, Kim HH, Lee HS, Lee DH. Comparison between Resectable Helicobacter pylori-Negative and -Positive Gastric Cancers. Gut Liver. 2016;10:212-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Matsuo T, Ito M, Takata S, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori-negative gastric cancer among Japanese. Helicobacter. 2011;16:415-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yang K, Lu L, Liu H, Wang X, Gao Y, Yang L, Li Y, Su M, Jin M, Khan S. A comprehensive update on early gastric cancer: defining terms, etiology, and alarming risk factors. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15:255-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wu J, Zhang H, Li L, Hu M, Chen L, Xu B, Song Q. A nomogram for predicting overall survival in patients with low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: A population-based analysis. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2020;40:301-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 61.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Balachandran VP, Gonen M, Smith JJ, DeMatteo RP. Nomograms in oncology: more than meets the eye. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e173-e180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1119] [Cited by in RCA: 2574] [Article Influence: 234.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lin J, Su H, Zhou Q, Pan J, Zhou L. Predictive value of nomogram based on Kyoto classification of gastritis to diagnosis of gastric cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2022;57:574-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Liu H, Li Z, Zhang Q, Li Q, Zhong H, Wang Y, Yang H, Li H, Wang X, Li K, Wang D, Kong X, He Z, Wang W, Wang L, Zhang D, Xu H, Yang L, Chen Y, Zhou Y, Xu Z. Multiinstitutional development and validation of a nomogram to predict prognosis of early-onset gastric cancer patients. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1007176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Huang B, Tian S, Zhan N, Ma J, Huang Z, Zhang C, Zhang H, Ming F, Liao F, Ji M, Zhang J, Liu Y, He P, Deng B, Hu J, Dong W. Accurate diagnosis and prognosis prediction of gastric cancer using deep learning on digital pathological images: A retrospective multicentre study. EBioMedicine. 2021;73:103631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Saka A, Yagi K, Nimura S. Endoscopic and histological features of gastric cancers after successful Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:524-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bui C, Lin LY, Wu CY, Chiu YW, Chiou HY. Association between Emotional Eating and Frequency of Unhealthy Food Consumption among Taiwanese Adolescents. Nutrients. 2021;13:2739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gao J, Fei JQ, Jiang LJ, Yao WQ, Lin B, and Guo HW. [Reliability and validity of a simplified food frequency questionnaire for dietary pattern investigation]. Yingyang Xuebao. 2011;33:452-456. |

| 21. | Tsai CJ, Leitzmann MF, Hu FB, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL. Frequent nut consumption and decreased risk of cholecystectomy in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:76-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32099] [Cited by in RCA: 39638] [Article Influence: 1016.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Machlowska J, Baj J, Sitarz M, Maciejewski R, Sitarz R. Gastric Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Genomic Characteristics and Treatment Strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:4012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 897] [Cited by in RCA: 969] [Article Influence: 161.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Spence AD, Cardwell CR, McMenamin ÚC, Hicks BM, Johnston BT, Murray LJ, Coleman HG. Adenocarcinoma risk in gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Paragomi P, Dabo B, Pelucchi C, Bonzi R, Bako AT, Sanusi NM, Nguyen QH, Zhang ZF, Palli D, Ferraroni M, Vu KT, Yu GP, Turati F, Zaridze D, Maximovitch D, Hu J, Mu L, Boccia S, Pastorino R, Tsugane S, Hidaka A, Kurtz RC, Lagiou A, Lagiou P, Camargo MC, Curado MP, Lunet N, Vioque J, Boffetta P, Negri E, La Vecchia C, Luu HN. The Association between Peptic Ulcer Disease and Gastric Cancer: Results from the Stomach Cancer Pooling (StoP) Project Consortium. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:4905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Solaymani-Dodaran M, Logan RF, West J, Card T, Coupland C. Risk of oesophageal cancer in Barrett's oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal reflux. Gut. 2004;53:1070-1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Derakhshan MH, Malekzadeh R, Watabe H, Yazdanbod A, Fyfe V, Kazemi A, Rakhshani N, Didevar R, Sotoudeh M, Zolfeghari AA, McColl KE. Combination of gastric atrophy, reflux symptoms and histological subtype indicates two distinct aetiologies of gastric cardia cancer. Gut. 2008;57:298-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wiseman M. The second World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research expert report. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67:253-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 557] [Cited by in RCA: 667] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Andrici J, Eslick GD. Hot Food and Beverage Consumption and the Risk of Esophageal Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:952-960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Masukume G, Mmbaga BT, Dzamalala CP, Mlombe YB, Finch P, Nyakunga-Maro G, Mremi A, Middleton DRS, Narh CT, Chasimpha SJD, Abedi-Ardekani B, Menya D, Schüz J, McCormack V. A very-hot food and beverage thermal exposure index and esophageal cancer risk in Malawi and Tanzania: findings from the ESCCAPE case-control studies. Br J Cancer. 2022;127:1106-1115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Abedi-Ardekani B, Kamangar F, Sotoudeh M, Villar S, Islami F, Aghcheli K, Nasrollahzadeh D, Taghavi N, Dawsey SM, Abnet CC, Hewitt SM, Fahimi S, Saidi F, Brennan P, Boffetta P, Malekzadeh R, Hainaut P. Extremely high Tp53 mutation load in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Golestan Province, Iran. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wang Y, Guo J, Yu F, Tian Y, Wu Y, Cui L, Liu LE. The association between soy-based food and soy isoflavone intake and the risk of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sci Food Agric. 2021;101:5314-5324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yu J, Bi X, Yu B, Chen D. Isoflavones: Anti-Inflammatory Benefit and Possible Caveats. Nutrients. 2016;8:361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Huang H, Krishnan HB, Pham Q, Yu LL, Wang TT. Soy and Gut Microbiota: Interaction and Implication for Human Health. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64:8695-8709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Karsli-Ceppioglu S, Ngollo M, Adjakly M, Dagdemir A, Judes G, Lebert A, Boiteux JP, Penault-LLorca F, Bignon YJ, Guy L, Bernard-Gallon D. Genome-wide DNA methylation modified by soy phytoestrogens: role for epigenetic therapeutics in prostate cancer? OMICS. 2015;19:209-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Karimi P, Islami F, Anandasabapathy S, Freedman ND, Kamangar F. Gastric cancer: descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, screening, and prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:700-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1159] [Cited by in RCA: 1381] [Article Influence: 115.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Cai Q, Zhu C, Yuan Y, Feng Q, Feng Y, Hao Y, Li J, Zhang K, Ye G, Ye L, Lv N, Zhang S, Liu C, Li M, Liu Q, Li R, Pan J, Yang X, Zhu X, Li Y, Lao B, Ling A, Chen H, Li X, Xu P, Zhou J, Liu B, Du Z, Du Y, Li Z; Gastrointestinal Early Cancer Prevention & Treatment Alliance of China (GECA). Development and validation of a prediction rule for estimating gastric cancer risk in the Chinese high-risk population: a nationwide multicentre study. Gut. 2019;68:1576-1587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/