Published online Dec 14, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i46.112664

Revised: September 17, 2025

Accepted: November 3, 2025

Published online: December 14, 2025

Processing time: 130 Days and 6.8 Hours

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is a cancer with a poor prognosis, characterized by distinct geo

To investigate if ethnic differences (Han vs Kazakh) cause molecular variations in ESCC patients via genomic sequencing 299 samples.

Here, we sequenced samples from 299 ESCC patients collected from Henan Key Laboratory for Esophageal Cancer Research and National Key Laboratory of Metabolic Dysregulation and Esophageal Cancer Prevention and Treat

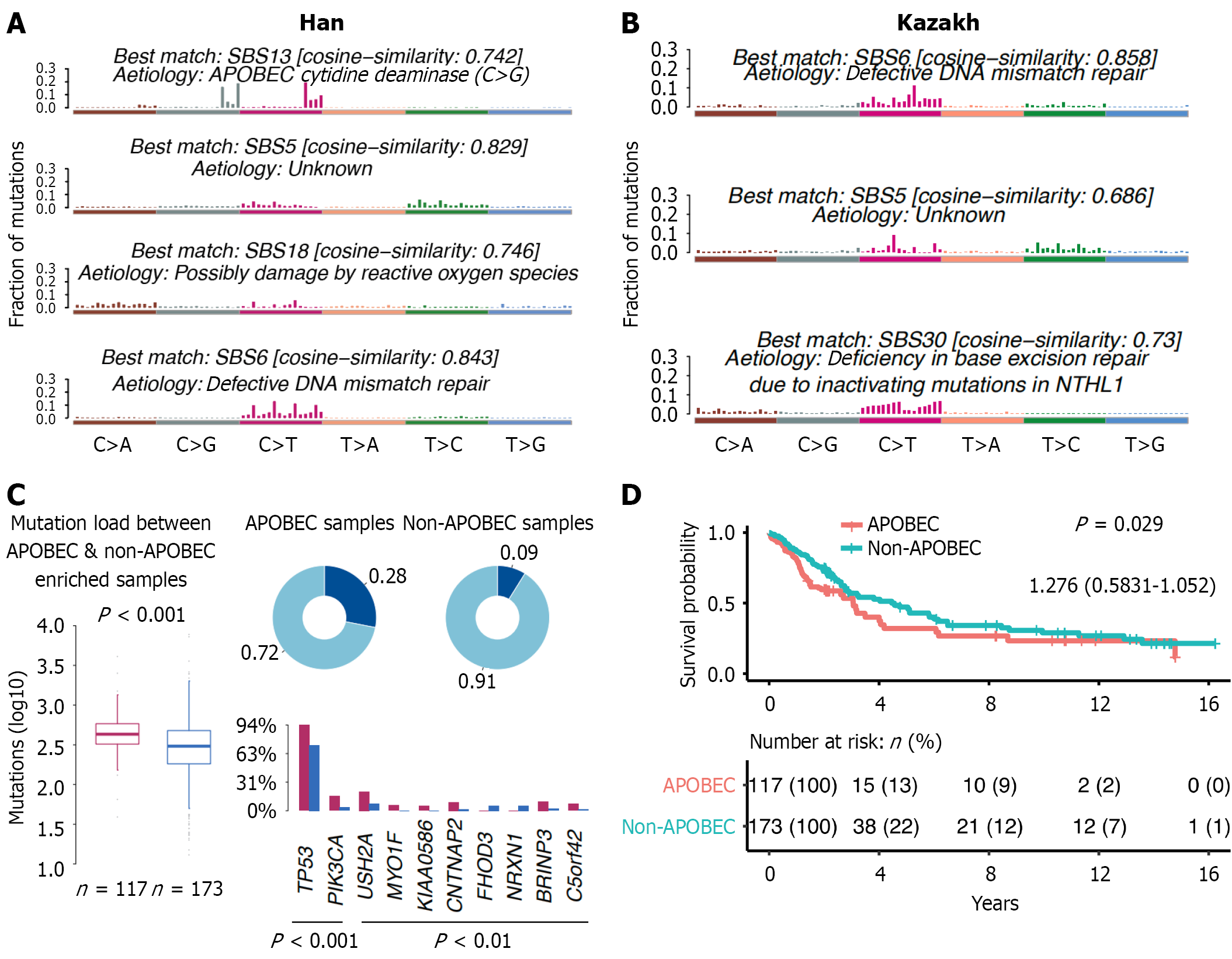

ESCC patients of Kazakh ethnicity present with a later age of onset compared to Han. Kazakh patients exhibit a slightly higher tumor mutation burden compared to their Han counterparts. Three genes GIGYF1, CACNA1D, and ACOT11 exhibited mutation frequencies threefold higher in Kazakh patients than in Han. This enrichment may be associated with Kazakhs’ adaptation to cold climates and consumption of high-calorie diets. Among Han patients, the apolipoprotein B messenger RNA-editing enzyme catalytic polypeptide (APOBEC)-associated single base substitutions (SBS) 13 mutational signature is more prevalent, whereas SBS6, indicative of DNA mismatch repair deficiency, is more common in Kazakh patients. Additionally, Han Chinese patients with APOBEC-enriched tumors exhibit a significantly higher mutation load than those without. Moreover, patients lacking the APOBEC signature demonstrate superior survival probability compared to the APOBEC-enriched group.

Living environment and diet are major factors in the development of ESCC. Genomic difference may provide guidance for the formulation of clinical treatment plans for ESCC from different ethnics regions.

Core Tip: This study aimed to explore if ethnic differences (Han vs Kazakh) cause molecular variations in Chinese esopha

- Citation: Wei MX, Lei LL, Xu RH, Liu YX, Wang R, Han WL, Fan ZM, Xiao FK, Sheyhidin I, Ma L, Ku JW, Yin MZ, Ji AF, Bao QD, Gao SG, Han XN, Li XM, Chen PN, Zhao XK, Song X, Wang LD. Ethnic genomic differences in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: Whole-exome sequencing of Han and Kazakh populations in China. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(46): 112664

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i46/112664.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i46.112664

Over the past few centuries, many well-designed cancer treatment methods have been introduced. These include surgical treatment, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, phototherapy, and molecular targeted cancer therapy after 1970[1]. Cancer treat

Disease phenotypes not only result from interactions between different genes within the host but also from the interplay between genes and environment[8]. Consequently, research on gene-environment interactions is crucial in understanding how genetic heterogeneity is influenced by various environmental agents[8,9], giving more enlightenment on the biological nature of cancer, improving the capacity to identify the susceptible gene that interacts with other factors[10,11], helping to single out why some individuals exposed to a specific agent develop cancer and others do not, and predicting the population subgroups that are more susceptible to cancer[12,13]. Current research suggests that low intake of fruits and vegetables, smoking and drinking, poor nutritional status, and the use of hot beverages may be the main risk factors contributing to the high incidence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC)[14,15]. Additional ESCC risk factors include comorbid gastrointestinal conditions, prior head/neck malignancies, high-risk human papilloma virus infection, tylosis, socioeconomic disadvantage, and suboptimal oral hygiene. The relative contribution of specific risk factors to disease development may vary significantly across geographic regions and ethnic populations[16,17].

Esophageal cancer is an aggressive and invasive disease[18], ranks the sixth leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide[19] with ESCC accounting for over 90% of total esophageal cancer in China. ESCC has poor prognosis with the 5-year survival rates around 20%-30% probably due to the difficulty in early diagnosis and the lack of effective the

Since 2012, there have been dozens of investigations published using the whole-genome sequence or whole-exome sequence (WES) strategy to explore the genetics of ESCC. These studies depicted the general mutational landscape of ESCC, including the significantly mutated genes such as TP53, CDKN2A, EP300, PIK3CA, and NOTCH1, the commonly influenced pathways such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-protein kinase B (AKT) axis, cell cycle, and histone modification, and the commonly identified age-related and apolipoprotein B messenger RNA-editing enzyme catalytic polypeptide (APOBEC) enzymes-related mutational signatures[24,25].

However, what are the reasons for the significant differences in survival between the Kazakh ethnic group and the Han ethnic group? Is the current treatment guideline for ESCC in China applicable to patients of other ethnic groups with ESCC? Analysis of clinical variables-related genomic features is essential for translational research. Here, we compared the genomic features difference between Han and Kazakh ESCC patients in China, to distinguish the molecular basis underlying the striking racial disparities in ESCC, and discuss the reason for the difference.

A total of 299 ESCC patients were included in this study, with 290 from Han region and 9 from Kazakh region. All the patients were collected from the database of Henan Key Laboratory for Esophageal Cancer Research and National Key Laboratory of Metabolic Dysregulation and Esophageal Cancer Prevention and Treatment of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhengzhou University. Patient inclusion criteria: (1) Underwent radical surgical treatment; (2) Complete clinicopathological information available; and (3) Postoperative pathological diagnosis confirmed as primary ESCC with a definite histopathological type. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou University (Ethics approval number: No. 2024-KY-2336-002).

Patient basic information was collected, including sex and age; clinicopathological data encompassed tumor differentiation grade, lymph node metastasis status, and pathological stage (Union for International Cancer Control, 2017). Follow-up was conducted for 299 patients with detailed addresses or contact information on record, utilizing telephone interviews and home visits. Follow-up began at diagnosis, with evaluations every 3 months initially, transitioning to annual assessments starting from the second year. The follow-up period concluded in May 2024. Death was defined as the endpoint event.

WES was performed on 299 paired fresh-frozen ESCC tumor tissues and matched blood samples. Genomic DNA was extracted from both tissue and blood samples using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Netherlands; Cat. 69504), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentration was precisely quantified using Qubit 2.0. Samples meeting the criteria of ≥ 20 ng/μL concentration and a minimum total mass of 0.6 μg were used for library preparation by Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co. Ltd (Beijing, China).

Whole exome libraries were constructed as described previously[26]. Briefly, DNA underwent fragmentation, end repair, 3’ end adenylation, and adapter ligation. Following size selection and polymerase chain reaction amplification using the NEB Next® Ultra DNA library prep kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, United States; Cat. E7530 L), the initial libraries were amplified with a high-fidelity polymerase to generate a sufficient quantity of the exome library. Upon completion of library construction, quantification was performed using Qubit 3.0 (Invitrogen, United States) and the NGS3K/Caliper system. Libraries were then subjected to cluster generation and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, generating 150 bp paired-end reads.

WES was performed on DNA extracted from all tumor tissues and matched blood samples, utilizing a capture system covering 64 Mb of the human genome (GRCh37). Stacked bar plots depicting clinicopathological characteristics were generated using the ggplot2 package in R (version 4.1.2). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and χ2 tests were employed to compare the clinicopathological features of ESCC patients across different geographic regions. Waterfall plots were constructed using the maftools package in R[27]. The mafCompare function was used to identify differentially mutated genes between patient groups, defined as genes with a mutation frequency ≥ 5% and P < 0.05. The somatic interactions function was employed to analyze the mutual exclusivity and co-occurrence of mutations. Mutation sites within genes were visualized using the lollipopPlot2 function. APOBEC enrichment scores were estimated using the trinucleotide matrix function, and samples were classified as either APOBEC-enriched or non-APOBEC-enriched. These two groups were then compared to identify differentially altered genes.

Signature analysis comprised the following steps: (1) Estimate signatures: This function runs non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) over a range of potential signature numbers and assesses the goodness of fit using the cophenetic correlation coefficient; (2) Plot cophenetic: This function generates an elbow plot to aid in determining the optimal number of signatures. The optimal number typically corresponds to the point where the cophenetic correlation exhibits a significant drop; (3) Extract signatures: This function applies NMF to decompose the mutational matrix into n signatures, where n is determined based on steps (1) and (2). If a reliable estimate of n is already available, these preceding steps can be omitted; (4) Compare signatures: The extracted signatures from step 3 are compared against known signatures from the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) database (single base substitutions (SBS) 1, SBS2, SBS3 etc.). Cosine similarity is calculated to identify the best-matching COSMIC signature(s) for each extracted signature; and (5) Plot signatures: Visualizes the extracted mutational signatures.

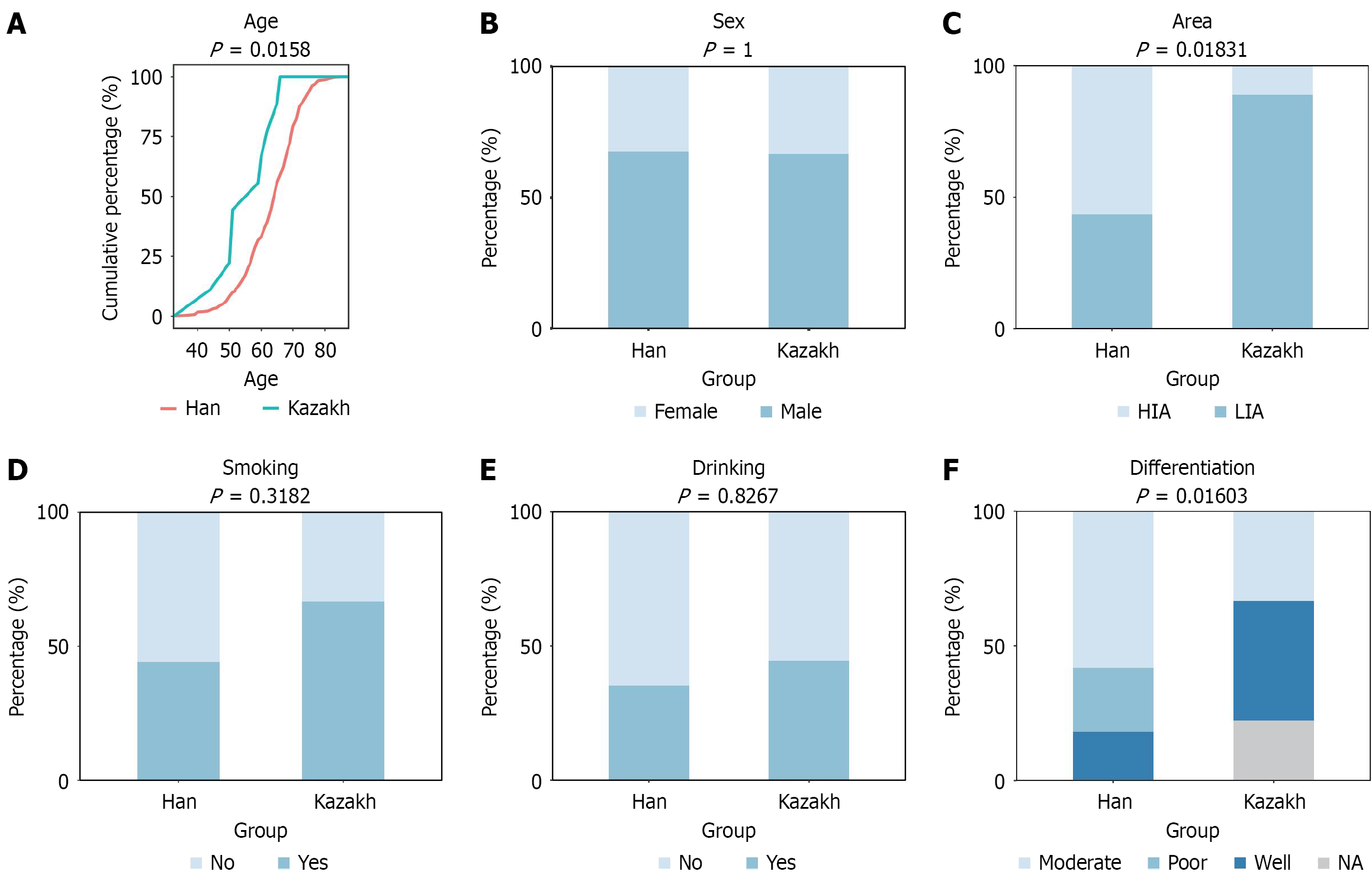

In this study, we generated WES data using the Illumina platform for both Han (n = 290) and Kazakh (n = 9) ethnic groups with ESCC. To robustly identify ethnic-biased mutated genes, we first assessed the distributions of key clinico

In the exonic coding regions of Han Chinese ESCC patients, a total of 242460 somatic mutations were identified, com

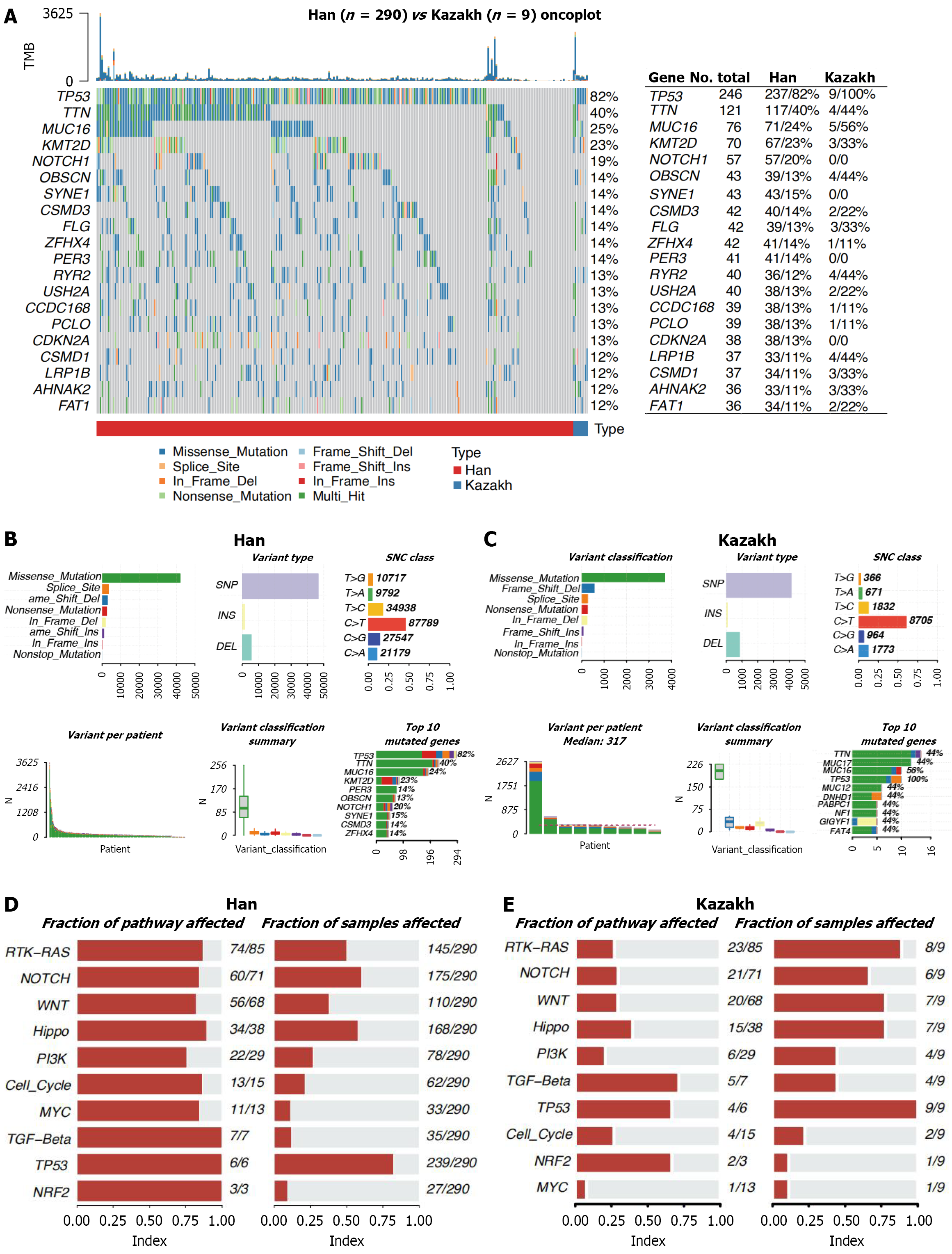

As the most important tumor suppressor, the non-silent mutation frequency of TP53 was 82% in 299 tumors, which was consistent with previous reports[39-41]. The types and relative positions of confirmed somatic mutations are shown in the transcript of TP53[40]. Red dots, nonsense mutations, and green dots, missense mutations, are the main variant classification for Han ESCC patients. However, green dots, missense mutation and blue dots, frame shift del are the main variant classification for Kazakh ESCC patients.

Recognizing somatic mutations as the molecular basis of tumor mutational burden (TMB), we characterized genome-wide variations by analyzing somatic mutation data from ESCC patients. An overview of the analytical strategy is presented in Figure 2B and C. Analysis revealed that missense mutations, splice site mutations, and frameshift deletions were the three most frequent variant types in Han Chinese patients (Figure 2B). In contrast, for Kazakh patients, splice site mutations ranked as the second most frequent variant type (Figure 2C). Single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) constituted the vast majority of all variant types in both ethnic groups (Figure 2B and C), with C > T substitutions being the most common SNV class (Figure 2B and C). Moreover, we displayed the number of mutated bases in each of the patients, with a median value of 85 for Han group, 210 for Kazakh (Figure 2B and C). The top 10 mutated genes in Han were TP53, TTN, MUC16, KMT2D, PER3, OBSCN, NOTCH1, SYNE1, CSMD3, and ZFHX4 (Figure 2B). The top 10 mutated genes in Kazakh were TTN, MUC17, MUC16, TP53, MUC12, DNHD1, PABPC1, NF1, GIGYF1 and FAT4 (Figure 2C)[42].

Genes were mapped to known oncogenic pathways, and pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the oncogenic pathways function in Maftools. This analysis quantifies the frequency of altered genes within each pathway and calculates the fraction of samples harboring mutations in genes belonging to that pathway. Pathways are then ranked by the number of mutated genes they contain. For Han Chinese patients, the most frequently altered pathways (with 100% of their constituent genes mutated in at least one sample) were transforming growth factor-beta, TP53, and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2). However, these pathways were mutated in 12%, 82%, and 9% of samples, respectively. Other enriched pathways included MYC (mutated in 11% of samples), cell-cycle (21%), PI3K (27%), and Hippo (58%) (Figure 2D). For Kazakh Chinese patients, the transforming growth factor-beta, TP53, and NRF2 pathways were also commonly altered. Enrichment levels for other pathways were: MYC (mutated in 11% of samples), cell-cycle (22%), PI3K (44%), and Hippo (78%). Within the pathway plots (Figure 2D and E), tumor suppressor genes are denoted in red font, while oncogenes are shown in blue.

The median variant allele frequency (VAF) of mutations in the top 20 genes for Han Chinese and Kazakh ESCC patients is presented in Supplementary Figure 2A and B, respectively. Among Han patients, genes with a median VAF ≥ 25% included NOTCH1, CDKN2A, and TP53. In contrast, only TP53 met this threshold among Kazakh patients. Conver

Next, we investigated the co-occurrence of mutated genes. Significant associations (P < 0.05) were identified in Han Chinese patients (Supplementary Figure 2C). Specifically, mutations in MUC16 co-occurred with mutations in RYR2, CCDC168, OBSCN, FLG, SYNE1, and KMT2D. Mutations in KMT2D co-occurred with mutations in AHNAK2, FAT1, RYR2, and SYNE1. Mutations in ZFHX4 co-occurred with mutations in FAT1, CSMD1, and USH2A. Mutations in OBSCN co-occurred with mutations in KMT2C, FAT1, and CCDC168 (P < 0.05, Supplementary Figure 2C). In Kazakh patients (Supplementary Figure 2D), significant co-occurrence associations (P < 0.05) were observed. Mutations in TP53 and mutations in MYCBP2 and DNAH11. Mutations in DNAH11 and mutations in NF1 and FAT4. Mutations in FAT4 and mutations in NF1 (P < 0.05, Supplementary Figure 2D).

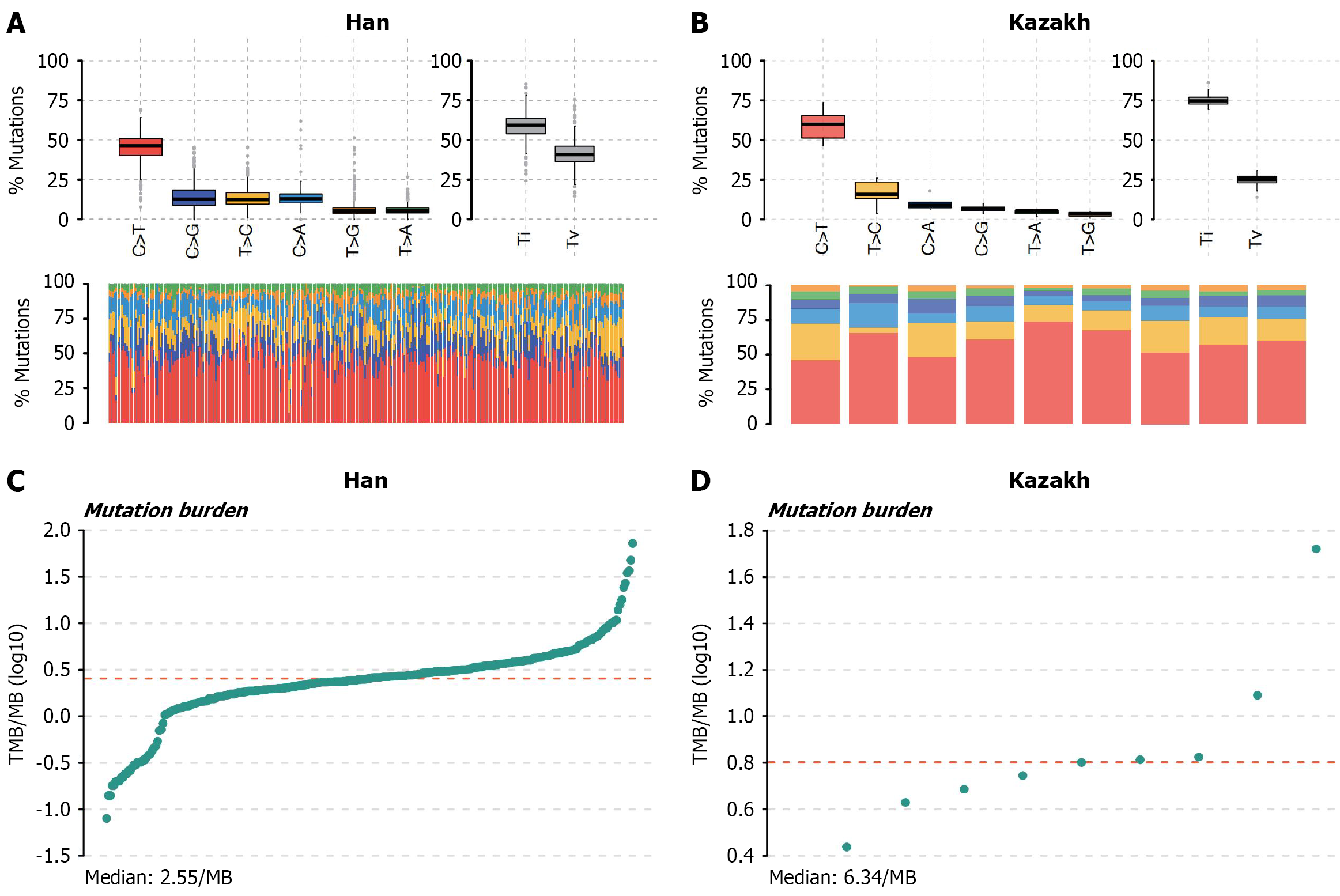

The transition/transversion (Ti/Tv) ratio is commonly used to assess the quality of variant calling. The transition and transversion plots (Figure 3A and B) categorize SNVs into six subtypes. We observed that the Ti/Tv ratio was approximately 2.0 in Han patients, but reached 3.0 in Kazakh patients. This difference may be attributed to a higher proportion of C > T transitions in the Han cohort compared to the Kazakh cohort. The elevated Ti/Tv ratio in the Han population may be associated with cytosine methylation in CpG islands, which promotes C > T transitions[43,44]. TMB was significantly higher in Kazakh ESCC patients compared to Han patients (Figure 3C and D). This elevated TMB implies that tumors in Kazakh patients are likely to produce a greater diversity and quantity of neoantigens. Consequently, these neoantigens have a higher probability of being recognized by the host immune system. Following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, which activates the body’s endogenous anti-tumor immune response, this enhanced neoantigen recognition may translate to a greater probability of tumor cell elimination[45]. No clustering of mutations was identified for Han and Kazakh patients (Supplementary Figure 3A for Han patients, and Supplementary Figure 3B for Kazakh patients).

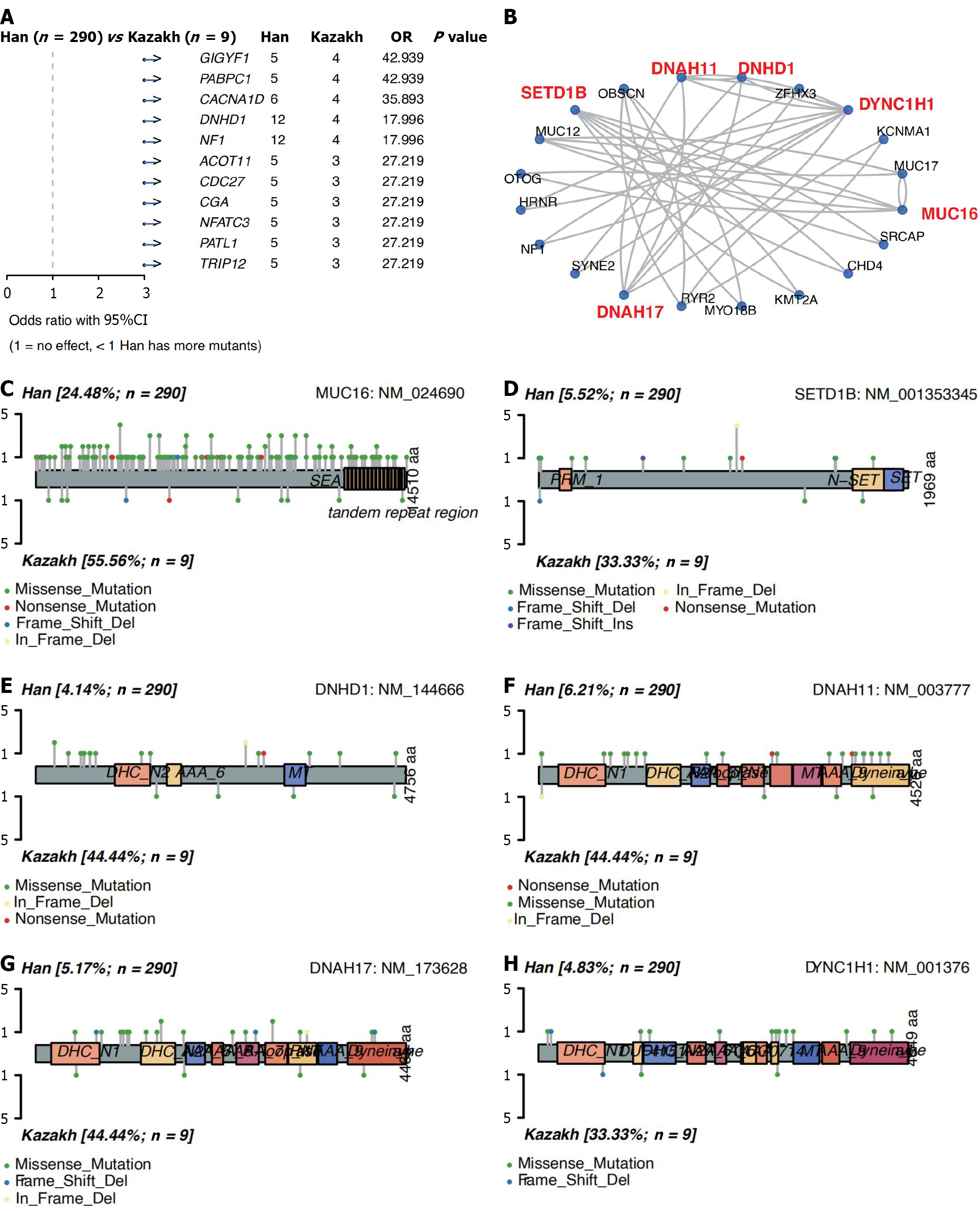

Clinical parameters contribute to tumor heterogeneity within a single cancer type. We utilized the mafCompare function to identify differentially mutated genes between the two cohorts, comparing the mutation frequency of each gene using Fisher’s exact tests. This comparison identified 11 differentially mutated genes between Han and Kazakh patients (P < 0.001, Figure 4A; P < 0.005, Supplementary Figure 4A). And all the 11 genes (GIGYF1, PABPC1, CACNA1D, DNHD1, NF1, ACOT11, CDC27, CGA, NFATC3, PATL1, TRIP12) are significantly enriched in Kazakh patients.

We then used the 37 differential genes and significantly mutated genes (P < 0.05 and mutation frequency ≥ 5%) to construct gene-gene association networks using the STRINGdb package (Figure 4B). Based on node centrality and interaction degree within the network, the interaction network was clustered and decomposed, yielding five distinct sub-networks (Supplementary Figure 4B). Among them, sub-network I consists of ZFH3 and SYNE2; sub-network II comprises KCNMA1, RYR2, OBSCN, and MYO18B; sub-network III includes OTOG, MUC12, MUC16, and MUC17, among which MUC16 is the central gene of the network; sub-network IV is composed of SRCAP, SETD1B, CHD4, and KMT2A, among which SETD1B is the central gene of this sub-network; sub-network V is made up of HRNR, DYNC1H1, NF1, DNAH17, DNHD1, and DNAH11, among which DYNC1H1, DNAH17, DNHD1, and DNAH11 are the central genes of this sub-network. Notably, sub-network III contains MUC16, a gene implicated in esophageal cancer onset. This sub-network may represent an important regulatory module potentially involved in esophageal cancer pathogenesis[46].

MUC16 mutation sites were uniformly distributed across the gene without enrichment in functional domains. Frame

From Figure 5A and B, we can see that SBS6 is associated with DNA mismatch repair deficiency in both groups, but the cosine similarity is higher in the Kazakh group (0.858 vs 0.843), indicating that the SBS6 characteristics of the Kazakh group are more similar to the known DNA mismatch repair deficiency characteristics. SBS5 exists in both groups, but the reason is unknown. The SBS5 characteristics of the Han ethnicity have a higher similarity to the known characteristics (0.829 vs 0.686). SBS13 and SBS18 only occur in the Han ethnicity, respectively related to APOBEC cytidine deaminase and possible reactive oxygen species (ROS) damage. SBS30 only occurs in the Kazakh group and is associated with base excision repair deficiency caused by NTHL1 gene inactivation mutation. Figure 5C shows that there is a significant difference in mutation burden between APOBEC-enriched samples and non-APOBEC-enriched samples in Han Chinese esophageal cancer patients (P < 0.001). In APOBEC-enriched samples, the mutation frequencies of genes such as TP53, PIK3CA, USH2A, and MYO1F are higher, while in non-APOBEC-enriched samples, the mutation frequencies of these genes are lower. Non-APOBEC-enriched Han patients has better survival than APOBEC-enriched Han patients (Figure 5D). Supplementary Figure 5A shows best possible value of Han (n = 4) and Kazakh patients (n = 3), and Supplementary Figure 5B shows that the cosine similarity between the mutation characteristics of different samples and the verified characteristics varies, indicating that there are multiple different mutation characteristics in Han Chinese patients. Supplementary Figure 5C also shows that there are multiple different mutation characteristics in Kazakh patients, but the similarity of certain characteristics is different compared to Han Chinese patients.

In general, cancer control strategies that work in high-income areas often don’t work in low-income areas. Because of differences in disease characteristics, health system capacity, sociocultural, treatment completion rates, and drug availability[47]. Our study found that diagnosis age was higher in Kazakh than in Han, and the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.016). The Kazakh ethnic group in China is mainly distributed in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Due to the relatively low level of economic development in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, the income of the Kazakh ethnic group is generally lower than the average level of China. However, the relevant policies of the Chinese government to support the economic development of ethnic minorities, including financial support, tax incentives, poverty alleviation, special industries and employment help, infrastructure construction, legal protection, education and personnel training, rural revitalization and so on[48-52]. These measures have greatly improved the economy and living standards of the Kazakh people in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

GIGYF1 gene is located in 7q22, with a total length of about 10kb, and binding to growth factor receptor-bound protein 10, and interacts with both the insulin and IGF1 receptors. Reports have proved that GIGYF1 is significantly expressed in autism[53], type 2 diabetes[54,55], and gastric cancer[35]. We first seen GIGYF1 highly expressed in ESCC patients of Kazakh. GIGYF1 promotes tumor growth by activating the extracellular regulated protein kinases (ERK) and AKT signaling pathways. Its low expression can significantly inhibit the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and AKT, and block the downstream pro-survival signals[35]. This indicator can be used as a basis for evaluating the feasibility of targeted inter

Previous studies proved that the dietary calcium intake was inversely associated with the risk of esophageal cancer [odds ratio (OR) = 0.80, 95% confidence interval: 0.71-0.91]. And the protective function of dietary calcium intake was observed in esophageal squamous cell cancer[59,60]. In our study, the occurrence probability of CACNA1D gene in the patients with esophageal cancer of the Kazakh ESCC group is 3 times that of the Han ESCC group (OR = 35.893, P < 0.001). CACNA1D, the gene encoding the pore-forming α1-subunit of Cav1.3 calcium ion (Ca2+) channels, highly mutated in Kazakh ESCC patients, which may be associated with low calcium intake in Kazakh because of poorly infrastructure, weak medicines purchasing, and far away distribution of pharmacies. But its actual mechanism of its action needs to be explored through other molecular experiments. L-type calcium channel blockers (such as amlodipine and nifedipine) can block downstream carcinogenic signals by inhibiting intracellular Ca2+ influx. CACNA2D1 (also a calcium channel protein) is highly expressed in gastric cancer and promotes tumor growth. Its inhibitor (such as amlodipine) combined with chemotherapy can enhance the therapeutic effect[61,62]. L-type calcium channel blockers (such as amlodipine and nifedipine) can block downstream carcinogenic signals by inhibiting the influx of Ca2+[63]. Therefore, it provides feasibi

Lipid metabolism, which is associated with the tumor microenvironment[65], may affect the responsiveness of the cancer cells to immunotherapy[66]. Previous study explored the mechanisms involved in the regulation of lipid metabolism in ESCC, identified differentially expressed genes and developed a prognosis predictive model for aiding clinical decision-making, which included ACOT11[67]. Its connection to ESCC and lipid metabolism in this context is an area ripe for exploration. ACOT11 is an enzyme involved in the hydrolysis of acyl-CoA compounds, influencing fatty acid metabolism[67]. It is highly expressed in brown adipose tissue (BAT) and is affected by environmental temperature and food consumption[68,69]. In higher organisms, this gene is mostly distributed in the cytoplasm, mitochondria, peroxisome and endoplasmic reticulum. In mammalian tissues, this gene is widely distributed in the brain, liver, kidneys, heart, lungs, steroids, etc.[70,71]. BAT is a kind of adipose tissue used to break down excessive energy and thereby reduce energy storage. It contains a relatively large number of mitochondria. Among them, the energy metabolism of UCP-1[72] and the production of adenosine triphosphate provide a basis for non-shivering thermogenesis[73]. Kirkby demonstrated that in the BAT of mice, the expression of ACOT11 was upregulated at low temperatures[71]. The main function of ACOT11 is to reduce energy consumption and preserve heat in the body, which may be owing to the low-temperature environment and high-energy diets in Kazakh. Therefore, we can treat patients with ACOT11 mutations through two methods[2,74]. The first approach is to inhibit the fatty acid oxidation pathway. This can be achieved by knocking down acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase 1 to suppress fatty acid synthesis, and in combination with ACOT11 inhibition, it can effectively block lipid flow[75,76]. The second approach is immune microenvironment modulation. The APOBEC-ACOT11 axis, where ACOT11 mutations may enhance APOBEC activity, leading to an increase in TMB and an increase in the release of new antigens. Alternatively, by activating the cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate synthase-stimulator of interferon genes pathway, it promotes the secretion of type I interferons and the infiltration of T cells. Combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors[77-79]. The response rate of programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors was significantly increased in ESCC patients with high TMB (27% vs 6% in patients with low TMB)[30,80].

The analysis results of mutation signatures in the Han and Kazakh populations with ESCC revealed significant differences in the mechanisms of esophageal cancer occurrence between the two groups, which might be related to genetic background, environmental exposure, and lifestyle factors. In both the Han and Kazakh populations, the SBS6 signature related to DNA mismatch repair deficiency was detected, and the cosine similarity was higher in the Kazakh population (0.858 vs 0.843). This indicates that DNA mismatch repair deficiency may play an important role in the occurrence of esophageal cancer. Defects in the DNA mismatch repair system can lead to genomic instability, increasing the risk of mutation accumulation, thereby promoting the occurrence of cancer[81]. The SBS5 signature exists in both populations, but the reason is unknown. The SBS5 signature in the Han population has a higher similarity to the known signature (0.829 vs 0.686). This may suggest that the SBS5 signature has a more significant role in esophageal cancer in the Han population, but its specific pathogenic mechanism still requires further study. Future research can combine genomics and functional experiments to explore the potential pathogenic mechanism of the SBS5 signature[82]. The Han-specific SBS13 and SBS18 signatures may be related to the specific environmental exposure or genetic factors of this ethnic group. The SBS13 signature is related to the APOBEC cytidine deaminase (C > G), and the APOBEC family enzymes have been found in various cancers, and their activity may be affected by viral infections, inflammatory responses, and other factors[83]. In Han Chinese patients with ESCC, the mutation characteristics mediated by APOBEC3A/APOBEC3B (such as SBS2/SBS13) may be directly related to the chronic inflammation-induced ROS burst. ROS causes DNA single-strand breaks by oxidizing bases (such as 8-oxoguanine), and under replication stress, activates the cytidine deaminase activity of APOBEC3A, thereby catalyzing the transition from TC to TT/TA mutations. This process forms a positive feedback loop of oxidative damage-APOBEC activation-mutation accumulation[84]. Chronic infections of the upper digestive tract (such as Helicobacter pylori) may promote neutrophil infiltration by activating the nuclear factor kappa-B pathway, resulting in excessive production of mitochondrial ROS. This microenvironment is associated with the high expression of APOBEC3B in gastric adenocarcinoma, and a similar mechanism may exist in Han Chinese ESCC: Helicobacter pylori infection-gastric acid reflux-accumulation of ROS in esophageal mucosa-enhancement of APOBEC mutation characteristics[85-88]. For the high-risk Han population, the antioxidant intervention proposed by Liu et al[89] and Ou et al[90] can be adopted: Such as berberine (targeting NOX4) or green tea polyphenols (cleaving ROS), which can block the activation chain of APOBEC. APOBEC inhibitors (such as small molecule antagonists of APOBEC3G) combined with PD-1 antibodies may enhance the efficacy. The SBS18 signature may be related to ROS damage. ROS are produced during cellular metabolism, and excessive ROS can cause DNA damage and promote the occurrence of cancer[91]. The Kazakh-specific SBS30 signature is related to the inactivation mutation of the NTHL1 gene, which leads to a base excision repair defect. The NTHL1 gene encodes a protein involved in base excision repair, and its inactivation mutation can lead to DNA repair defects and increase the risk of mutation accumulation. This suggests that the occurrence of esophageal cancer in the Kazakh population may be related to specific genetic mutations or environmental factors.

Furthermore, through large-scale genomic data, neural network learning[92], generative adversarial networks learning[93], optimization algorithms, and the verification of important markers, applying generative adversarial networks to integrate the methylation and single-cell transcriptome data of Han/Kazakh ethnic groups, to analyze the epigenetic memory of environmental exposure, it can provide important references for the clinical treatment and diagnostic guidelines of esophageal cancer patients of different races.

Living environment and diet are major factors in the development of ESCC. Genomic differences may provide guidance for the formulation of clinical treatment plans for ESCC from different ethnics regions.

We would like to thank Wu HL (University of Chinese Academy of Sciences) and Xia CZ (School of life sciences, Zhengzhou University) for kindly providing analysis support.

| 1. | Sonkin D, Thomas A, Teicher BA. Cancer treatments: Past, present, and future. Cancer Genet. 2024;286-287:18-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 184.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liu H, Dilger JP. Different strategies for cancer treatment: Targeting cancer cells or their neighbors? Chin J Cancer Res. 2025;37:289-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chow RD, Long JB, Hassan S, Wheeler SB, Spees LP, Leapman MS, Hurwitz ME, McManus HD, Gross CP, Dinan MA. Disparities in immune and targeted therapy utilization for older US patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2023;7:pkad036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Monge C, Waldrup B, Carranza FG, Velazquez-Villarreal E. Comparative Genomic Analysis of Key Oncogenic Pathways in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Among Diverse Populations. Cancers (Basel). 2025;17:1309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zavala VA, Bracci PM, Carethers JM, Carvajal-Carmona L, Coggins NB, Cruz-Correa MR, Davis M, de Smith AJ, Dutil J, Figueiredo JC, Fox R, Graves KD, Gomez SL, Llera A, Neuhausen SL, Newman L, Nguyen T, Palmer JR, Palmer NR, Pérez-Stable EJ, Piawah S, Rodriquez EJ, Sanabria-Salas MC, Schmit SL, Serrano-Gomez SJ, Stern MC, Weitzel J, Yang JJ, Zabaleta J, Ziv E, Fejerman L. Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br J Cancer. 2021;124:315-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 663] [Cited by in RCA: 686] [Article Influence: 137.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Revels SL, Morris AM, Reddy RM, Akateh C, Wong SL. Racial disparities in esophageal cancer outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1136-1141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nobel TB, Lavery JA, Barbetta A, Gennarelli RL, Lidor AO, Jones DR, Molena D. National guidelines may reduce socioeconomic disparities in treatment selection for esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2019;32:doy111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359-E386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20108] [Cited by in RCA: 20720] [Article Influence: 1883.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (23)] |

| 9. | Hunter DJ. Gene-environment interactions in human diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:287-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 698] [Cited by in RCA: 761] [Article Influence: 36.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Amato R, Pinelli M, D'Andrea D, Miele G, Nicodemi M, Raiconi G, Cocozza S. A novel approach to simulate gene-environment interactions in complex diseases. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ramos RG, Olden K. Gene-environment interactions in the development of complex disease phenotypes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2008;5:4-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wu C, Jiang Y, Ren J, Cui Y, Ma S. Dissecting gene-environment interactions: A penalized robust approach accounting for hierarchical structures. Stat Med. 2018;37:437-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Thomas D. Methods for investigating gene-environment interactions in candidate pathway and genome-wide association studies. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:21-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | He Z, Zhao Y, Guo C, Liu Y, Sun M, Liu F, Wang X, Guo F, Chen K, Gao L, Ning T, Pan Y, Li Y, Zhang S, Lu C, Wang Z, Cai H, Ke Y. Prevalence and risk factors for esophageal squamous cell cancer and precursor lesions in Anyang, China: a population-based endoscopic survey. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1085-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | McCormack VA, Menya D, Munishi MO, Dzamalala C, Gasmelseed N, Leon Roux M, Assefa M, Osano O, Watts M, Mwasamwaja AO, Mmbaga BT, Murphy G, Abnet CC, Dawsey SM, Schüz J. Informing etiologic research priorities for squamous cell esophageal cancer in Africa: A review of setting-specific exposures to known and putative risk factors. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:259-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Abnet CC, Kamangar F, Islami F, Nasrollahzadeh D, Brennan P, Aghcheli K, Merat S, Pourshams A, Marjani HA, Ebadati A, Sotoudeh M, Boffetta P, Malekzadeh R, Dawsey SM. Tooth loss and lack of regular oral hygiene are associated with higher risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3062-3068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Guha N, Boffetta P, Wünsch Filho V, Eluf Neto J, Shangina O, Zaridze D, Curado MP, Koifman S, Matos E, Menezes A, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Fernandez L, Mates D, Daudt AW, Lissowska J, Dikshit R, Brennan P. Oral health and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and esophagus: results of two multicentric case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:1159-1173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jiang G, Wang Z, Cheng Z, Wang W, Lu S, Zhang Z, Anene CA, Khan F, Chen Y, Bailey E, Xu H, Dong Y, Chen P, Zhang Z, Gao D, Wang Z, Miao J, Xue X, Wang P, Zhang L, Gangeswaran R, Liu P, Chard Dunmall LS, Li J, Guo Y, Dong J, Lemoine NR, Li W, Wang J, Wang Y. The integrated molecular and histological analysis defines subtypes of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2024;15:8988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 56667] [Article Influence: 7083.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (135)] |

| 20. | Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:115-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11444] [Cited by in RCA: 13324] [Article Influence: 1332.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 21. | Liu J, Xie X, Zhou C, Peng S, Rao D, Fu J. Which factors are associated with actual 5-year survival of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41:e7-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gao J, Wang Q, Fu F, Zhao Y, Yang T, Li X, Sun Y, Hu H, Ma L, Miao L, Luo X, Ye T, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Huang Z, Li H, Shao L, Xu M, Zhao K, Zhang S, Zhang M, Wang J, Dai C, Shang X, An T, Zhang Y, Xiang J, Cao Z, Li B, Chen H. Comprehensive genomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal prognostic stratification for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10:223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhang YJ, Du Q, Zhu LJ, Zhang Y, Li XM, Pu HW, Chen X. Significance of expression of S100A11 and 14-3-3 proteins in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2014;22:4609-4614. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Li XC, Wang MY, Yang M, Dai HJ, Zhang BF, Wang W, Chu XL, Wang X, Zheng H, Niu RF, Zhang W, Chen KX. A mutational signature associated with alcohol consumption and prognostically significantly mutated driver genes in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:938-944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cui Y, Chen H, Xi R, Cui H, Zhao Y, Xu E, Yan T, Lu X, Huang F, Kong P, Li Y, Zhu X, Wang J, Zhu W, Wang J, Ma Y, Zhou Y, Guo S, Zhang L, Liu Y, Wang B, Xi Y, Sun R, Yu X, Zhai Y, Wang F, Yang J, Yang B, Cheng C, Liu J, Song B, Li H, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Cheng X, Zhan Q, Li Y, Liu Z. Whole-genome sequencing of 508 patients identifies key molecular features associated with poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Res. 2020;30:902-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhang Q, Lou Y, Yang J, Wang J, Feng J, Zhao Y, Wang L, Huang X, Fu Q, Ye M, Zhang X, Chen Y, Ma C, Ge H, Wang J, Wu J, Wei T, Chen Q, Wu J, Yu C, Xiao Y, Feng X, Guo G, Liang T, Bai X. Integrated multiomic analysis reveals comprehensive tumour heterogeneity and novel immunophenotypic classification in hepatocellular carcinomas. Gut. 2019;68:2019-2031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 37.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (13)] |

| 27. | Mayakonda A, Lin DC, Assenov Y, Plass C, Koeffler HP. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 2018;28:1747-1756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1228] [Cited by in RCA: 3463] [Article Influence: 432.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Li M, Zhang Z, Wang Q, Yi Y, Li B. Integrated cohort of esophageal squamous cell cancer reveals genomic features underlying clinical characteristics. Nat Commun. 2022;13:5268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Qin HD, Liao XY, Chen YB, Huang SY, Xue WQ, Li FF, Ge XS, Liu DQ, Cai Q, Long J, Li XZ, Hu YZ, Zhang SD, Zhang LJ, Lehrman B, Scott AF, Lin D, Zeng YX, Shugart YY, Jia WH. Genomic Characterization of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Reveals Critical Genes Underlying Tumorigenesis and Poor Prognosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:709-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zhang X, Wang Y, Meng L. Comparative genomic analysis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma: New opportunities towards molecularly targeted therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:1054-1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Liu Z, Zhao Y, Kong P, Liu Y, Huang J, Xu E, Wei W, Li G, Cheng X, Xue L, Li Y, Chen H, Wei S, Sun R, Cui H, Meng Y, Liu M, Li Y, Feng R, Yu X, Zhu R, Wu Y, Li L, Yang B, Ma Y, Wang J, Zhu W, Deng D, Xi Y, Wang F, Li H, Guo S, Zhuang X, Wang X, Jiao Y, Cui Y, Zhan Q. Integrated multi-omics profiling yields a clinically relevant molecular classification for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:181-195.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hou Q, Jiang Z, Li Z, Jiang M. Identification and Functional Validation of Radioresistance-Related Genes AHNAK2 and EVPL in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Exome and Transcriptome Sequencing Analyses. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;14:1131-1145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Li SQ, Jiang W, Zhu YC. Proteomics-based prognostic signature in colon adenocarcinoma patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Transl Cancer Res. 2025;14:3654-3669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Liu WJ, Zhao Y, Chen X, Miao ML, Zhang RQ. Epigenetic modifications in esophageal cancer: An evolving biomarker. Front Genet. 2022;13:1087479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zhu L, Yao Z, Luo Q, Liu Y, Zhao W, Shao C, Shao S, Cui F. Low Expression of GIGYF1 Inhibits Metastasis, Proliferation, and Promotes Apoptosis and Autophagy of Gastric Cancer Cells. Int J Med Sci. 2023;20:1038-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Zhang Y, Chen C, Liu Z, Guo H, Lu W, Hu W, Lin Z. PABPC1-induced stabilization of IFI27 mRNA promotes angiogenesis and malignant progression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma through exosomal miRNA-21-5p. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022;41:111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Phan NN, Wang CY, Chen CF, Sun Z, Lai MD, Lin YC. Voltage-gated calcium channels: Novel targets for cancer therapy. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:2059-2074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Liu F, Li X, Liu S, Ma T, Cai B, Liang L, Qu B, Zhang P, Du L, Huang X, Yu W. Genomic profiling of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma to reveal actionable genetic alterations. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:e16042-e16042. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Gao YB, Chen ZL, Li JG, Hu XD, Shi XJ, Sun ZM, Zhang F, Zhao ZR, Li ZT, Liu ZY, Zhao YD, Sun J, Zhou CC, Yao R, Wang SY, Wang P, Sun N, Zhang BH, Dong JS, Yu Y, Luo M, Feng XL, Shi SS, Zhou F, Tan FW, Qiu B, Li N, Shao K, Zhang LJ, Zhang LJ, Xue Q, Gao SG, He J. Genetic landscape of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1097-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 557] [Cited by in RCA: 569] [Article Influence: 47.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 40. | Song Y, Li L, Ou Y, Gao Z, Li E, Li X, Zhang W, Wang J, Xu L, Zhou Y, Ma X, Liu L, Zhao Z, Huang X, Fan J, Dong L, Chen G, Ma L, Yang J, Chen L, He M, Li M, Zhuang X, Huang K, Qiu K, Yin G, Guo G, Feng Q, Chen P, Wu Z, Wu J, Ma L, Zhao J, Luo L, Fu M, Xu B, Chen B, Li Y, Tong T, Wang M, Liu Z, Lin D, Zhang X, Yang H, Wang J, Zhan Q. Identification of genomic alterations in oesophageal squamous cell cancer. Nature. 2014;509:91-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in RCA: 875] [Article Influence: 72.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Zhang L, Zhou Y, Cheng C, Cui H, Cheng L, Kong P, Wang J, Li Y, Chen W, Song B, Wang F, Jia Z, Li L, Li Y, Yang B, Liu J, Shi R, Bi Y, Zhang Y, Wang J, Zhao Z, Hu X, Yang J, Li H, Gao Z, Chen G, Huang X, Yang X, Wan S, Chen C, Li B, Tan Y, Chen L, He M, Xie S, Li X, Zhuang X, Wang M, Xia Z, Luo L, Ma J, Dong B, Zhao J, Song Y, Ou Y, Li E, Xu L, Wang J, Xi Y, Li G, Xu E, Liang J, Yang X, Guo J, Chen X, Zhang Y, Li Q, Liu L, Li Y, Zhang X, Yang H, Lin D, Cheng X, Guo Y, Wang J, Zhan Q, Cui Y. Genomic Analyses Reveal Mutational Signatures and Frequently Altered Genes in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Am J Hum Genet. 2020;107:375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Fan A, Zhang Y, Cheng J, Li Y, Chen W. A novel prognostic model for prostate cancer based on androgen biosynthetic and catabolic pathways. Front Oncol. 2022;12:950094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Arabnejad M, Dawkins BA, Bush WS, White BC, Harkness AR, McKinney BA. Transition-transversion encoding and genetic relationship metric in ReliefF feature selection improves pathway enrichment in GWAS. BioData Min. 2018;11:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, Hartl C, Philippakis AA, del Angel G, Rivas MA, Hanna M, McKenna A, Fennell TJ, Kernytsky AM, Sivachenko AY, Cibulskis K, Gabriel SB, Altshuler D, Daly MJ. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43:491-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9842] [Cited by in RCA: 8582] [Article Influence: 572.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Vryza P, Fischer T, Mistakidi E, Zaravinos A. Tumor mutation burden in the prognosis and response of lung cancer patients to immune-checkpoint inhibition therapies. Transl Oncol. 2023;38:101788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Jonckheere N, Vincent A, Neve B, Van Seuningen I. Mucin expression, epigenetic regulation and patient survival: A toolkit of prognostic biomarkers in epithelial cancers. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2021;1876:188538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Pari V, Tirupakuzhi Vijayaraghavan BK, Biccard BM, Hashmi M. Evaluating cancer care in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Oncol. 2024;25:e179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Howell A. Spatioethnic Household Carbon Footprints in China and the Equity Implications of Climate Mitigation Policy: A Machine Learning Approach. Ann Am Assoc Geogr. 2024;114:958-976. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 49. | Wu X, He G. Changing Ethnic Stratification in Contemporary China. J Contemp China. 2016;25:938-954. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 50. | Sicular T, Yang X, Gustafsson B. The Rise of China's Global Middle Class in an International Context. China World Econ. 2022;30:5-27. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 51. | Liu J, Zhang Y. Health status and health disparity in China: a demographic and socioeconomic perspective. China Popul Dev Stud. 2019;2:301-322. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 52. | Zhang J, Zhou X, Xing Q, Li Y, Zhang L, Zhou Q, Lu Y, Zhai M, Bao J, Tang B. Sudden cardiac death in the Kazakh and Han peoples of Xinjiang, China: A comparative cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e18126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Chen G, Yu B, Tan S, Tan J, Jia X, Zhang Q, Zhang X, Jiang Q, Hua Y, Han Y, Luo S, Hoekzema K, Bernier RA, Earl RK, Kurtz-Nelson EC, Idleburg MJ, Madan-Khetarpal S, Clark R, Sebastian J, Fernandez-Jaen A, Alvarez S, King SD, Ramos LL, Santos MLS, Martin DM, Brooks D, Symonds JD, Cutcutache I, Pan Q, Hu Z, Yuan L, Eichler EE, Xia K, Guo H. GIGYF1 disruption associates with autism and impaired IGF-1R signaling. J Clin Invest. 2022;132:e159806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Thompson DJ, Genovese G, Halvardson J, Ulirsch JC, Wright DJ, Terao C, Davidsson OB, Day FR, Sulem P, Jiang Y, Danielsson M, Davies H, Dennis J, Dunlop MG, Easton DF, Fisher VA, Zink F, Houlston RS, Ingelsson M, Kar S, Kerrison ND, Kinnersley B, Kristjansson RP, Law PJ, Li R, Loveday C, Mattisson J, McCarroll SA, Murakami Y, Murray A, Olszewski P, Rychlicka-Buniowska E, Scott RA, Thorsteinsdottir U, Tomlinson I, Moghadam BT, Turnbull C, Wareham NJ, Gudbjartsson DF; International Lung Cancer Consortium (INTEGRAL-ILCCO); Breast Cancer Association Consortium; Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2; Endometrial Cancer Association Consortium; Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium; Prostate Cancer Association Group to Investigate Cancer Associated Alterations in the Genome (PRACTICAL) Consortium; Kidney Cancer GWAS Meta-Analysis Project; eQTLGen Consortium; Biobank-based Integrative Omics Study (BIOS) Consortium; 23andMe Research Team, Kamatani Y, Hoffmann ER, Jackson SP, Stefansson K, Auton A, Ong KK, Machiela MJ, Loh PR, Dumanski JP, Chanock SJ, Forsberg LA, Perry JRB. Genetic predisposition to mosaic Y chromosome loss in blood. Nature. 2019;575:652-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 36.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Zhao Y, Stankovic S, Koprulu M, Wheeler E, Day FR, Lango Allen H, Kerrison ND, Pietzner M, Loh PR, Wareham NJ, Langenberg C, Ong KK, Perry JRB. GIGYF1 loss of function is associated with clonal mosaicism and adverse metabolic health. Nat Commun. 2021;12:4178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Mcbrearty N, Bahal D, Platero S. Fast-tracking drug development with biomarkers and companion diagnostics. J Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2024;10:3. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 57. | Takashima N, Ishiguro H, Kuwabara Y, Kimura M, Haruki N, Ando T, Kurehara H, Sugito N, Mori R, Fujii Y. Expression and prognostic roles of PABPC1 in esophageal cancer: correlation with tumor progression and postoperative survival. Oncol Rep. 2006;15:667-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Pu J, Zhang T, Zhang D, He K, Chen Y, Sun X, Long W. High-Expression of Cytoplasmic Poly (A) Binding Protein 1 (PABPC1) as a Prognostic Biomarker for Early-Stage Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:5361-5372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Li Q, Cui L, Tian Y, Cui H, Li L, Dou W, Li H, Wang L. Protective Effect of Dietary Calcium Intake on Esophageal Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients. 2017;9:510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Qin X, Jia G, Zhou X, Yang Z. Diet and Esophageal Cancer Risk: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies. Adv Nutr. 2022;13:2207-2216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Yokobori T. Editorial Comment on: Functions and Clinical Significance of CACNA2D1 in Gastric Cancer: "Potential for Targeted Therapy against Gastric Cancer Stem Cells Using the Clinically Available Calcium Channel Blocker". Ann Surg Oncol. 2022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Liu H. A Prospective for the Potential Effect of Local Anesthetics on Stem-Like Cells in Colon Cancer. Glob J Med Res. 2020;20:35-38. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Liu X, Shen B, Zhou J, Hao J, Wang J. The L-type calcium channel CaV1.3: A potential target for cancer therapy. J Cell Mol Med. 2024;28:e70123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Hengrui L. Nav channels in cancers: Non-classical roles. Glob J Cancer Ther. 2020. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 65. | Tao M, Luo J, Gu T, Yu X, Song Z, Jun Y, Gu H, Han K, Huang X, Yu W, Sun S, Zhang Z, Liu L, Chen X, Zhang L, Luo C, Wang Q. LPCAT1 reprogramming cholesterol metabolism promotes the progression of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Tang Y, Chen Z, Zuo Q, Kang Y. Regulation of CD8+ T cells by lipid metabolism in cancer progression. Cell Mol Immunol. 2024;21:1215-1230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Shen GY, Yang PJ, Zhang WS, Chen JB, Tian QY, Zhang Y, Han B. Identification of a Prognostic Gene Signature Based on Lipid Metabolism-Related Genes in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2023;16:959-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Zhang Y, Li Y, Niepel MW, Kawano Y, Han S, Liu S, Marsili A, Larsen PR, Lee CH, Cohen DE. Targeted deletion of thioesterase superfamily member 1 promotes energy expenditure and protects against obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5417-5422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:277-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4296] [Cited by in RCA: 4910] [Article Influence: 223.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Yamada J. Long-chain acyl-CoA hydrolase in the brain. Amino Acids. 2005;28:273-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Kirkby B, Roman N, Kobe B, Kellie S, Forwood JK. Functional and structural properties of mammalian acyl-coenzyme A thioesterases. Prog Lipid Res. 2010;49:366-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Shabalina IG, Backlund EC, Bar-Tana J, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Within brown-fat cells, UCP1-mediated fatty acid-induced uncoupling is independent of fatty acid metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:642-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Hunt MC, Tillander V, Alexson SE. Regulation of peroxisomal lipid metabolism: the role of acyl-CoA and coenzyme A metabolizing enzymes. Biochimie. 2014;98:45-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Jin Z, Zhang W, Liu H, Ding A, Lin Y, Wu SX, Lin J. Potential Therapeutic Application of Local Anesthetics in Cancer Treatment. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2022;17:326-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Qian H, Gu CW, Liu YZ, Zhao BS. [Knockdown of ACC1 promotes migration of esophageal cancer cell]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2023;45:482-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Liu H. Effect of Traditional Medicine on Clinical Cancer. BJSTR. 2020;30. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 77. | Yang J, Xiang T, Zhu S, Lao Y, Wang Y, Liu T, Li K, Ma Y, Zhong C, Zhang S, Tan W, Lin D, Wu C. Comprehensive Analyses Reveal Effects on Tumor Immune Infiltration and Immunotherapy Response of APOBEC Mutagenesis and Its Molecular Mechanisms in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:2551-2571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Liu H, Wang P. CRISPR screening and cell line IC50 data reveal novel key genes for trametinib resistance. Clin Exp Med. 2024;25:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Liu H, Karsidag M, Chhatwal K, Wang P, Tang T. Single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing analysis reveals CENPA as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in cancers. PLoS One. 2025;20:e0314745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Hengrui L. An example of toxic medicine used in Traditional Chinese Medicine for cancer treatment. J Tradit Chin Med. 2023;43:209-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Peltomäki P, de la Chapelle A. Mutations predisposing to hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 1997;71:93-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SA, Behjati S, Biankin AV, Bignell GR, Bolli N, Borg A, Børresen-Dale AL, Boyault S, Burkhardt B, Butler AP, Caldas C, Davies HR, Desmedt C, Eils R, Eyfjörd JE, Foekens JA, Greaves M, Hosoda F, Hutter B, Ilicic T, Imbeaud S, Imielinski M, Jäger N, Jones DT, Jones D, Knappskog S, Kool M, Lakhani SR, López-Otín C, Martin S, Munshi NC, Nakamura H, Northcott PA, Pajic M, Papaemmanuil E, Paradiso A, Pearson JV, Puente XS, Raine K, Ramakrishna M, Richardson AL, Richter J, Rosenstiel P, Schlesner M, Schumacher TN, Span PN, Teague JW, Totoki Y, Tutt AN, Valdés-Mas R, van Buuren MM, van 't Veer L, Vincent-Salomon A, Waddell N, Yates LR; Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative; ICGC Breast Cancer Consortium; ICGC MMML-Seq Consortium; ICGC PedBrain, Zucman-Rossi J, Futreal PA, McDermott U, Lichter P, Meyerson M, Grimmond SM, Siebert R, Campo E, Shibata T, Pfister SM, Campbell PJ, Stratton MR. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7533] [Cited by in RCA: 7562] [Article Influence: 581.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 83. | Roberts SA, Lawrence MS, Klimczak LJ, Grimm SA, Fargo D, Stojanov P, Kiezun A, Kryukov GV, Carter SL, Saksena G, Harris S, Shah RR, Resnick MA, Getz G, Gordenin DA. An APOBEC cytidine deaminase mutagenesis pattern is widespread in human cancers. Nat Genet. 2013;45:970-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 812] [Cited by in RCA: 960] [Article Influence: 73.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Yang Y, Liu N, Gong L. An overview of the functions and mechanisms of APOBEC3A in tumorigenesis. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2024;14:4637-4648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Burns MB, Lackey L, Carpenter MA, Rathore A, Land AM, Leonard B, Refsland EW, Kotandeniya D, Tretyakova N, Nikas JB, Yee D, Temiz NA, Donohue DE, McDougle RM, Brown WL, Law EK, Harris RS. APOBEC3B is an enzymatic source of mutation in breast cancer. Nature. 2013;494:366-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 696] [Cited by in RCA: 702] [Article Influence: 54.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Ou L, Zhu Z, Hao Y, Li Q, Liu H, Chen Q, Peng C, Zhang C, Zou Y, Jia J, Li H, Wang Y, Su B, Lai Y, Chen M, Chen H, Feng Z, Zhang G, Yao M. 1,3,6-Trigalloylglucose: A Novel Potent Anti-Helicobacter pylori Adhesion Agent Derived from Aqueous Extracts of Terminalia chebula Retz. Molecules. 2024;29:1161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Ou L, Liu HR, Shi XY, Peng C, Zou YJ, Jia JW, Li H, Zhu ZX, Wang YH, Su BM, Lai YQ, Chen MY, Zhu WX, Feng Z, Zhang GM, Yao MC. Terminalia chebula Retz. aqueous extract inhibits the Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammatory response by regulating the inflammasome signaling and ER-stress pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;320:117428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Ou L, Chen H, Hao Y, Liu H, Zhu Z, Li Q, Feng Z, Zhang G, Yao M. In vitro antibacterial activity of neochebulinic acid from aqueous extract of Terminalia chebula Retz against Helicobacter pylori. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2025;25:287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Liu H, Gu RJ, Li C, Wang JX, Dong CS. Potential of traditional Chinese medicine in managing and preventing Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese military. World J Gastroenterol. 2025;31:103754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Ou L, Liu H, Peng C, Zou Y, Jia J, Li H, Feng Z, Zhang G, Yao M. Helicobacter pylori infection facilitates cell migration and potentially impact clinical outcomes in gastric cancer. Heliyon. 2024;10:e37046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:44-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8502] [Cited by in RCA: 9073] [Article Influence: 453.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Su X, Hu P, Li D, Zhao B, Niu Z, Herget T, Yu PS, Hu L. Interpretable identification of cancer genes across biological networks via transformer-powered graph representation learning. Nat Biomed Eng. 2025;9:371-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Ai X, Smith MC, Feltus FA. Generative adversarial networks applied to gene expression analysis: An interdisciplinary perspective. Comp Sys Onco. 2023;3:e1050. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/