Published online Dec 14, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i46.112530

Revised: September 23, 2025

Accepted: October 23, 2025

Published online: December 14, 2025

Processing time: 133 Days and 13.5 Hours

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver cancer, with high mortality at advanced stages. Loco-regional treatment including: Radiofrequency (RF) or transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is decided according to the size, and the site of the tumor, according to practice guidelines. Alpha fetoprotein (AFP), the most used biomarker in the guidelines, although specific, lacks sensitivity. New biomarkers are needed to understand the underlying pathophysiology, and to be used in clinical practice.

To study the effect of loco-regional treatment on telomere length, as a diagnostic and short-term (3 months) prognostic marker.

This is a prospective cohort study, and includes 60 patients visiting Ain Shams University Hospitals. The patients were divided into 2 groups: 30 patients with liver cirrhosis (group 1) and 30 HCC patients undergoing RF or TACE (group 2). Laboratory investigations for all patients included: Telomere length in peripheral leukocytes by polymerase chain reaction, AFP, and liver function. In the HCC group, the aforementioned laboratory investigations with abdominal triphasic computed tomography with contrast were performed at baseline, and after 3 months.

With regard to age, Child-Pugh and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease scores, there was no statistically significant correlation with telomere length. However, there was a correlation between telomere length and age, and both scores before and after 3 months of treatment among HCC patients. On dividing the HCC group according to tumor size with a cutoff of 5 cm, and performing the Mann-Whitney test we found that at baseline telomere length was significantly lower among cases with tumor size ≥ 5 cm than in those with tumor size < 5 cm (30 patients; P = 0.03). In addition, we found a positive Spearman's rank correlation between telomere length and tumor size in the

Telomere length in leukocytes is a potential marker in HCC tumor prognosis. Further research using telomerase activity and telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter gene mutation in a larger cohort is recommended.

Core Tip: We examined the telomere length in peripheral leukocytes, as a biomarker for diagnosis and short-term prognosis of loco-regional therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). We found that in patients with HCC or chronic liver disease, the telomere length is short. When we used a cutoff of 5 cm it was found that in patients with larger tumors, the telomere length was shorter. Moreover, in large tumors the telomere length increased, as the size of the tumor increased. This is the first study to include Egyptian patients. We hope this study paves the way for further research on telomeres in HCC prognosis, and diagnosis.

- Citation: El-Nakeep S, AbdelAziz H, Michael TG, ElGhandour AM, Abdelsattar HA, Awad FMR, Kasi A. Clinical utility of telomeres as diagnostic and short-term prognostic markers in loco-regional treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(46): 112530

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i46/112530.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i46.112530

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver malignancy, constituting 75%-85% of liver cancer cases[1]. In Egypt, most of the patients with HCC are male, and HCC is considered the commonest cancer overall, forming 19.7% of all cancer cases in 2018[2]. Loco-regional therapy for early, and intermediate HCC, is recommended in the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) guidelines[3]. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), and sorafenib are considered palliative measures for BCLC classes B and C, while radiofrequency (RF) and microwave ablation are used in earlier stages as curative measures[3,4].

In the 1930s, Creighton et al[5] and Muller et al[6] first introduced the concept and the term “telomere” (meaning “end-part”), when examining insects, and corn end-chromosomes. The average length of the telomere repeats in human diploid cells is 92 repeats[7,8]. Human telomere length ranges from 5-15 kb of the TTAGGG motif[9]. Telomeres are tandem DNA repeats of the sequence TTAGGG covered by shelterin, or telosome, a cap protein that protects the DNA ending from damage, and allows for telomerase enzyme regulation[10]. Natural progressive telomere shortening is caused by the inability to replicate the last segment of the 3’ strand during cell division[11]. “End-replication problem” means the DNA polymerase cannot replicate the last part of the DNA in the 3’ to 5’ direction, thus the telomere shortens with each new replication forming a “biological clock”. This biological clock is “reset” in 85% of all cancers by reactivation of the telomerase enzyme[12]. Interstitial telomeric sequences are telomeric repeats in the middle of the chromosomes, and they are considered telomere motifs forming a structural pattern[9].

The telomere length is variable in different individuals, and is longer in females than males from birth. Telomere loss in leukocytes is highest in memory T cells, and natural killer cells than other types with aging[8]. However, a recent study examined the telomere methylation genes as a prognostic marker for HCC, and found that telomere length and DNA methylation has a bidirectional relation with HCC, where the telomere length has a statistically significant correlation with HCC in B lymphocytes, native T lymphocytes, and granulocytes; among all leukocytes[13].

Normally the liver does not show telomerase activation. However, in chronic liver disease (CLD) due to the chronic inflammatory state, the telomere length is shortened rapidly by repeated replication, causing a chromosomal instability, and resulting in telomerase reactivation[14]. Moreover, in chronic inflammation the elevated inflammatory cytokines inhibit telomerase activity, thus telomere shortening occurs rapidly i.e., “cellular senescence”. Antioxidants, and anti-inflammatory agents, along with gene therapy could activate the telomerase enzyme, and have been tried to counteract cellular aging[12].

The enzyme telomerase consists of three parts including: Telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), telomerase RNA component (TERC), and protein associates such as the cap covering protein shelterin. The role of telomerase enzyme in advancing HCC was assessed by Li et al[15] and they found that telomerase activity affects the survival, and prognosis of HCC patients.

The present study aimed to examine the effect of telomere length on the diagnosis, and short-term (3 months) prognosis of loco-regional therapy in Egyptian HCC patients as compared to the gold standard for diagnosis, and follow-up of HCC cases.

This is a prospective observational cohort study conducted in the Hepatology outpatient clinics, and included patients admitted to the inpatient Hepatogastroenterology Unit, Internal Medicine Department, in Ain Shams University Hospitals. The study took place from February 2021 to April 2025.

This study included sixty Egyptian patients over 18 years old of both genders with CLD or HCC, who were divided into two groups: (1) Group 1 (control group): Included 30 patients with liver cirrhosis as diagnosed by clinical examination, laboratory investigations, pelviabdominal ultrasound, and fibroscan; and (2) Group 2: Included 30 HCC patients who were scheduled to undergo RF, or TACE. Patients with HCC were diagnosed according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines, and the gold standard for diagnosis of HCC using computed tomography (CT) triphasic scan with contrast and alpha fetoprotein (AFP).

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) History of previous or current non-HCC malignancies; (2) History of previous liver resection or hepatobiliary operation; (3) History of previous local-regional therapy (e.g., in the case of HCC recurrence); (4) History of any hepatic focal lesions (HFLs) other HCC (hemangioma, metastasis etc.); (5) Presence of acute infections or acute illness other than the liver-related condition; and (6) Receiving direct acting antivirals (DAAs) in the last 12 months for hepatitis C virus (HCV).

We performed sample size calculation as a perquisite to submitting the protocol in 2020. Using PASS 11 program for sample size calculation, power 90% margin error ± 0.05 and by reviewing previous studies results[16], the total mean telomere length of all samples was 2.5 ± 0.284 kb in HCC compared to 4.8 ± 1.530 kb in regenerative nodules (cirrhotic patients); based on this, the required sample size was 60 patients (30 in each group) to be sufficient to detect the difference between groups as regards to telomere length. The sampling method was purposive sampling.

Epidemiologic information: Sociodemographic characteristics (age and sex), alcohol intake, cigarette smoking, HCC family history, presence of hypertension or diabetes were included in this study.

Full clinical history: Hematemesis, endoscopic intervention, hepatic encephalopathy, ascites and tapping, bleeding per orifices, lower limb edema, HCV or hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and treatment were included in this study.

The patients underwent the following examinations: (1) Liver function tests: Serum alanine aminotransferase, serum aspartate aminotransferase, total, and direct bilirubin, total protein, serum albumin, international normalized ratio (INR); (2) Complete blood picture: Platelet count and volume, hemoglobin level, mean corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, white blood cell, differential count; (3) Kidney function: Creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, Na, K; (4) AFP level in serum; (5) Viral markers: Hepatitis B surface antigen Ag and HCV antibody; (6) Calculation of Child-Pugh score to assess the clinical severity of cirrhosis according to degree of ascites, encephalopathy, serum bilirubin, albumin, and prothrombin time. A score of 5 to 6 was considered class A (well-compensated disease), 7 to 9 was class B (significant functional compromise), and 10 to 15 was class C (decompensated disease); and (7) Calculation of Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) NA score which included laboratory data for Na, total bilirubin, creatine, and INR using the validated online formula.

Abdominal ultrasonography: The liver size and texture, spleen size, portal and splenic vein diameters, presence of ascites, size and number of the tumors were included. Doppler ultrasound was conducted to assess the presence of portal vein thrombosis. In addition, fibro-scan was performed to confirm liver cirrhosis.

Contrasted abdominal triphasic: CT, or triphasic (dynamic) magnetic resonance imaging to determine the site, number, size of HFLs (especially largest), and presence of vascular invasion.

Principle of the assay for telomere length: Assay results based on the measurement of telomere length in the cirrhotic group were compared to those in the HCC group at the time of diagnosis, and at follow up after three months of loco-regional therapy using quantitative PCR (qPCR) according to the method described by Cawthon[17].

First, 2 mL of peripheral venous blood was collected, and EDTA was added to avoid coagulation. The samples were labeled and frozen at -80 °C for subsequent analyses.

Directly before DNA extraction, blood samples were removed from the freezer and underwent a thawing process on ice to avoid DNA degeneration. Extracted DNA was frozen to -20 °C until telomere length measurement was performed.

DNA extraction was performed using The Thermo ScientificTM GeneJETTM Whole Blood Genomic DNA Purification Mini Kit following the manufacturer's manual as follows: (1) 20 μL of proteinase K solution was added to 200 μL of whole blood, and then mixed using a vortex mixer; (2) 400 μL of lysis solution was added and then mixed using a vortex mixer or pipetting to obtain a uniform suspension; (3) The sample was incubated for 10 minutes at 56 °C, then mixed using a vortex mixer, a shaking water bath, a rocking platform, or a thermomixer, until the cells were completely lysed; (4) 200 μL of ethanol (96%-100%) was added and a pipette was used to mix the solution; (5) The prepared mixture was transferred to a spin column, and centrifuged at 6000 × g for 1 minute. The collection tube containing the flow-through solution was discarded, and the sample was placed into a new 2 mL collection tube; (6) 500 μL of wash buffer WB I was added (in addition to ethanol), and then centrifuged at 8000 × g for 1 minute. The flow-through solution was discarded, and the sample was then added to the collection tube; (7) 500 μL of wash buffer II was added (in addition to ethanol) and then centrifuged at ≥ 20000 × g for 3 minutes; (8) The collection tube was emptied and the purification column was placed into the tube. The sample was then centrifuged at ≥ 20000 × g for 1 minute; (9) The collection tube which contained the flow-through solution was discarded, and the column was transferred to a sterile 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube; (10) 200 μL of elution buffer was added to the center of the column membrane in order to remove genomic DNA. The sample was incubated for 2 minutes at room temperature, then centrifuged at 8000 × g for 1 minute; and (11) DNA purity was assessed by measuring the A260/A280 ratio using a spectrophotometer, all the samples showed ratios between 1.8 and 2.0. Extracted DNA was frozen to -20 °C until telomere length was measured.

We determined the telomere length using the modified single well multiplex qPCR in addition to the estimated absolute telomere length.

(1) The total telomere length per reaction (sample) was measured using the quantification cycle (Cq) of telomeres by a standard calibration curve formed through serial dilution of a synthesized telomeric oligonucleotide. The numbers per reaction of the genome copy (in the sample) were measured by the Cq of albumin with a standard calibration curve formed through serial dilution of a synthesized albumin oligonucleotide. The absolute telomere length (kb) per human diploid genome was then assessed with the following formula: Divide the total telomere length per reaction by the diploid genome copies of albumin per reaction; (2) The telomere length standard calibration curve was formed by using a synthesized 84 bp oligonucleotide carrying 14 TTAGGG repeats (Macrogen) and a molecular weight (MW) of 25113. The weight of one molecule of the telomere standard is equivalent to the MW divided by Avogadro’s number (25113/6.02 × 1023 = 4.17 × 10-20 g). The highest concentration in the calibration curve (TEL STD A) of the telomere oligomer was one picogram per reaction (15 μL), with (1 × 10-12/4.17 × 10-20 = 2.4 × 107) oligomer molecules in TEL STD A. Five serial dilutions of TEL STD from qPCR analysis were needed to generate the standard calibration curve (from 2.4 × 107 to 1.5 × 106 molecules). Thus, we calculated the telomere sequence length in TEL STD A as follows: [2.4 × 107 × 84 (oligomer length) = 2.02 × 106 kb]; (3) The albumin standard calibration curve was formed by the synthesis of 44 mer-oligonucleotide (AAATGCTGCACAGAATCCTTGGTGAACAGGCGACCATGCTTTTC; Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States) that has a MW of 13516 for estimation of the number of genome copy per reaction. The weight of a single molecule of albumin oligonucleotide equaled (13516/6.02 × 1023 = 2.25 × 10-20 g). The highest concentration of the standard calibration curve (Alb STD A) was 0.2 picogram of albumin oligomer per reaction, or (0.2 × 10-12/2.25 × 10-12 = 8.9 × 106 copies) of the albumin amplicon in Alb STD A. The Alb STD A equals (4.45 × 106) diploid genome copies, since there are 2 copies of albumin per diploid genome. The standard curve linearity for both telomere and albumin assays showed R² values consistently greater than 0.99; (4) PCR primers were made according to a former study[18]. A short fixed-length product (76 bp) can be generated using the telomere primers telg (ACACTAAGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTAGTGT), and telc (TGTTAGGTATCCCTATCCCTATCCCTATCCCTATCCC TAACA). Only telg is capable of priming DNA synthesis along native telomeric DNA sequences, while telc primer is not capable of priming DNA synthesis due to the mismatch in its 3′; (5) A product of (98 bp) can be generated using the albumin primers: Albu (CGGCGGCGGGCGGCGCGGGCTGGGCGGaaatgctgcacagaatccttg), and albd (GCCCGGCCCGCCGCGCCCGTCCCGCCGgaaaagcatggtcg cctgtt). The non-templated coding strand 5′ ends (capitalized bases) were used to ensure that the PCR product’s Tm value of albumin at a temperature of 88 °C was more than the telomere product at a temperature of 74 °C; (6) SYBR Green I fluorescence signals collected at 88 °C denote the amount of albumin amplicons only, while the collected signals at 74 °C amount to the amplicons of both the albumin and telomere. As, the number of copies of albumin were considerably lower than the template of the telomere, we can ignore the signals from albumin at 74 °C, when we compare them to the telomere signals for each DNA sample. Thus, we conducted the quantification of both telomere and albumin in the same well to decrease the variability of input DNA in the PCR’s quantity, and efficiency; (7) We ran the end volume of each qPCR (15 μL contained about 40 ng of DNA) in a Bio-Rad iQ5 rt-PCR detection system. Five different concentrations were prepared through serial dilution of synthesized telomere and albumin oligonucleotides, and assessed them in duplicate for each 96-well plate. The collected data were used in the generation of the standard calibration curves of sample quantitation of unknown value; and (8) Each DNA sample was assayed in duplicate. The terminal concentrations of reagents in the PCR were 1 × Power up SYBR Green I (Applied Biosystems by Thermo Fisher Scientific), 10 mmol/L Tris–HCl pH 8.3, 50 mmol/L KCl, 3 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.2 mmol/L each of dNTP and 1 mmol/L DTT. Reactions were run with telomere primers (telg/telc) at 360 nM each, and a single copy gene of albumin primers (albu/albd) at 90 nM each. A 15 minutes thermal cycling profile at 95 °C was used, 2 cycles of 15 seconds at 94 °C, 15 seconds at 49 °C, and 32 cycles of 15 seconds at 94 °C, 10 seconds at 62 °C, and 15 seconds at 74 °C with one acquisition, 10 seconds at 84 °C, and 15 seconds at 88 °C with one acquisition. While the temperature of 74 °C reads supplied the amplification Cq values of the telomere template (with albumin signal maintained at baseline); the temperature of 88 °C reads supplied the amplification Cq values for the albumin template.

The collected data were coded, tabulated, and statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) software version 28.0, IBM Corp., Chicago, United States, 2021.

Quantitative data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, if normally distributed the data were described as mean ± SD as well as minimum and maximum of the range, and then compared using the Independent t-test and paired t-test. The data which were not normally distributed were described as median (1st-3rd interquartile) minimum and maximum of the range, and then compared using the Mann-Whitney test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Correlations were tested using the Spearman correlation test.

Qualitative data were described as number and percentage and then compared using the χ2 test and Marginal homogeneity test. A P value < 0.050 was considered statistically significant.

Scatter plot and linear regression were analyzed using Jamovi version 2.7 and R version 4.5. A receiver operating curve was generated to illustrate the predictive performance of a binary classifier. Multivariate linear regression was performed to analyze the relationship between multiple variables.

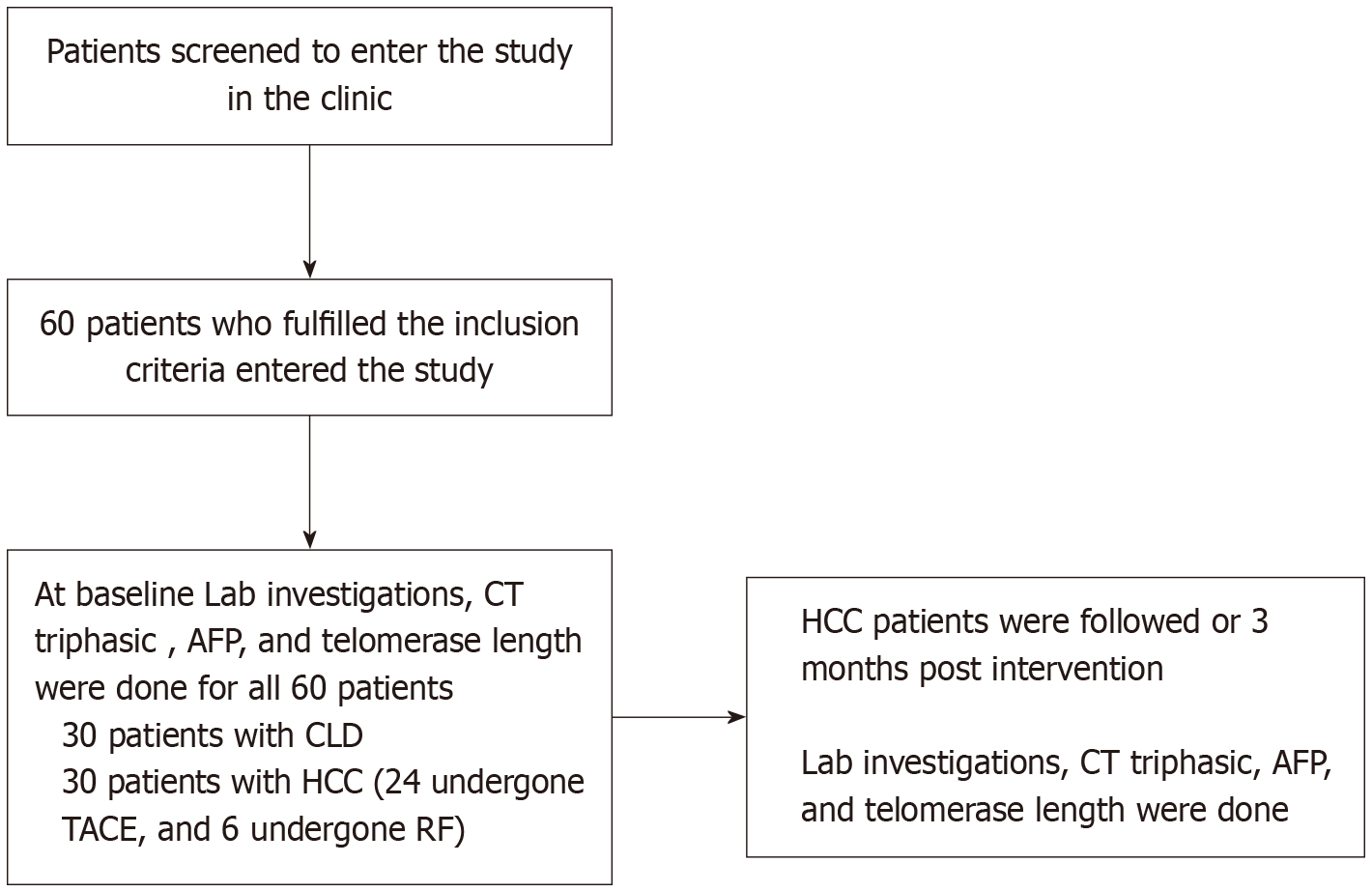

This was a prospective cohort observational study which included 60 patients divided into 2 groups: (1) Group 1 (control): 30 patients with liver cirrhosis; and (2) Group 2: 30 HCC patients who underwent RF or TACE, then followed for 3 months. None of the patients underwent local surgery or liver resection during the 3-month follow-up period. Figure 1 shows the flow chart of the study performed by Revman.

All included patients had only one or two HFLs (no patients had more than 2 HFLs, and all were BCLC stages 0, A or B). No other stages were included as shown in Table 1. There were no patients with portal vein invasion according to our inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Telomere length with variables | HCC group | CLD group | |

| Sex | Male | 1.2 (1.0-1.8) | 1.4 (1.1-2.2) |

| Female | 1.9 (1.5-2.1) | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | |

| P value | 0.120 | 0.391 | |

| Smoking | Yes | 1.2 (0.9-1.8) | 1.4 (1.0-1.8) |

| No | 1.3 (1.0-2.1) | 1.2 (1.1-1.9) | |

| P value | 0.378 | 1.000 | |

| Hypertension | Yes | 1.3 (0.9-1.8) | 1.3 (0.8-1.6) |

| No | 1.3 (1.0-1.8) | 1.4 (1.1-1.9) | |

| P value | 0.851 | 0.568 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | Yes | 1.1 (0.9-1.5) | 1.2 (0.9-1.5) |

| No | 1.5 (1.2-2.1) | 1.5 (1.1-2.2) | |

| P value | 0.061 | 0.128 | |

| Size | ≥ 5 cm | 1.1 (1.0-1.5) | |

| < 5 cm | 1.9 (1.3-2.2) | ||

| P value | 0.030a | ||

| BCLC staging | 0 | 1.7 (1.1-2.0) | |

| A | 2.1 (1.3-2.3) | ||

| B | 1.1 (1.0-1.5) | ||

| P value | 0.075 | ||

Group 1 (cirrhotic group) included 23 males (76.7%), and 7 females (23.3%). Their ages ranged from 49.0 to 86.0 years, with a mean of 61.5 ± 8.6 years. Group 2 (HCC group) included 27 males (90.0%) and 3 females (10.00%). Their ages ranged from 50.0 to 78.0 years, with a mean of 64.0 ± 8.2 years. With regard to demographic characteristics, there was no statistically significant difference between the HCC and CLD groups regarding age, sex, smoking, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus as shown in Table 2.

Table 3 shows that, regarding liver function tests, there was a statistically significant decrease in albumin, and a statistically significant increase in INR after 3 months of treatment. In addition, AFP was significantly lower after 3 months of treatment. There was no statistically significant change in telomere length after 3 months of treatment. Table 3 shows that more than half of HCC cases showed a complete response to treatment.

| Variables | n | % | |

| Possible cause | HCV | 25 | 83.3 |

| HBV | 2 | 6.7 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 10.0 | |

| HCC treatment | TACE | 24 | 80.0 |

| RF | 6 | 20.0 | |

| Response | Complete | 16 | 53.3 |

| Partial | 14 | 46.7 | |

| Size (cm2) | Median (1st-3rd IQ) | 26.3 (8.4-59.3) | |

| Range | 1.2-138.0 | ||

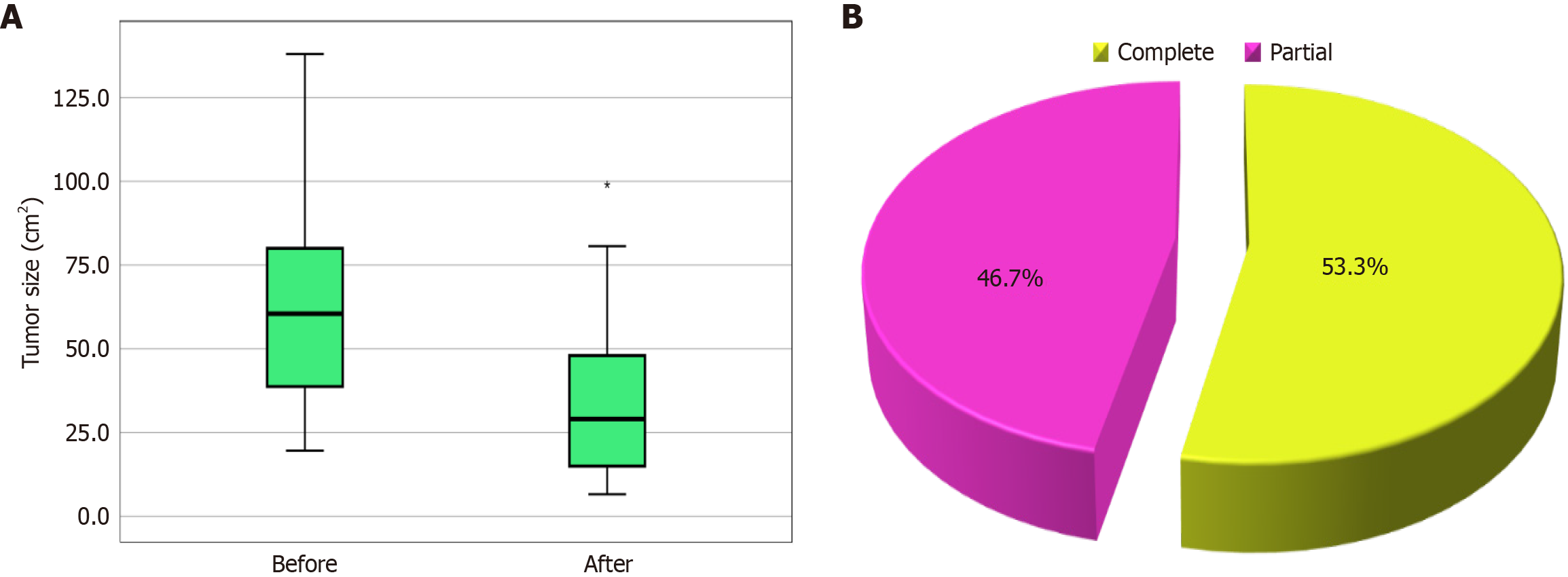

Table 4 shows the tumor characteristics, and there was a significant decrease in the number and size of HCC tumors after 3 months of treatment. Figure 2A shows tumor size before and after treatment in the HCC group. Figure 2B shows tumor response in the HCC group. Four patients had two tumors, and all 4 had large tumors beyond curative intervention, while the rest of the patients had only one tumor. Tumor size is presented in Table 4.

The change in tumor size is shown in the 14 patients who had a partial response, as the remaining patients (16 patients) had a complete response with complete elimination of the tumor (reaching 0 cm in diameter) after therapy (Tables 3 and 4).

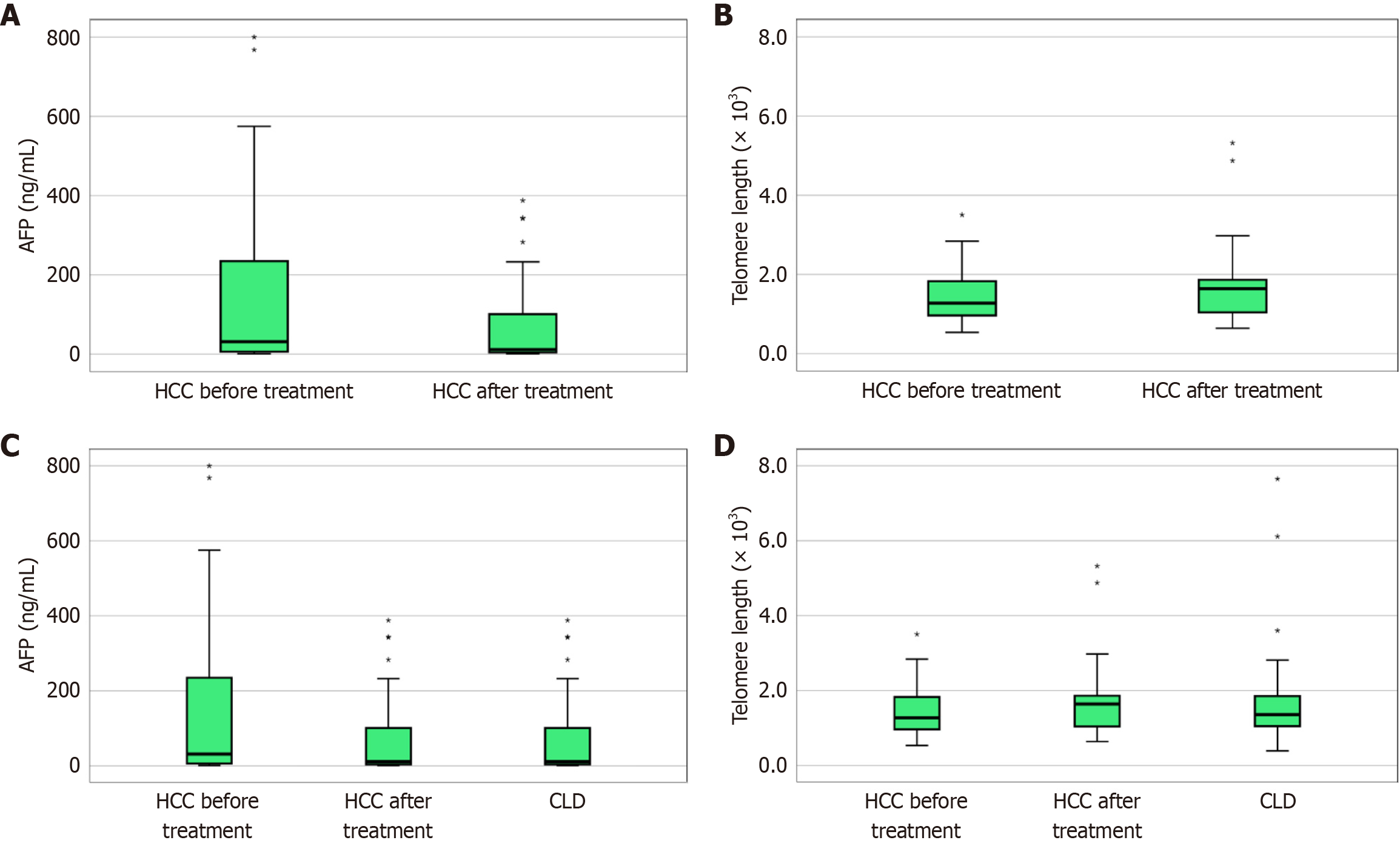

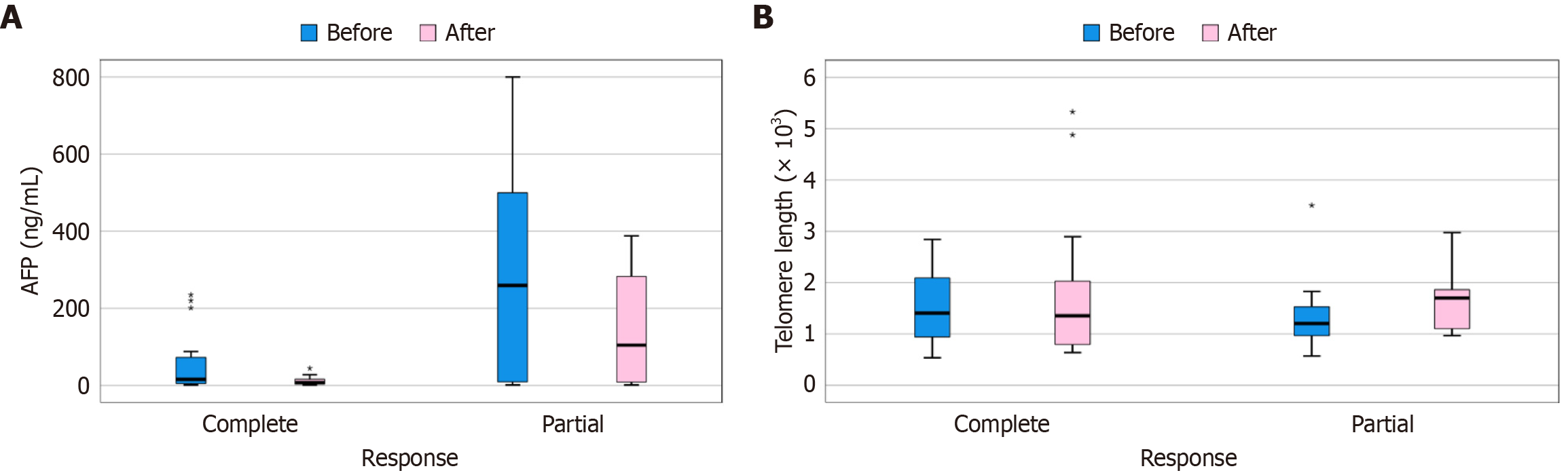

Regarding liver function tests, there was a statistically significant decrease in albumin level, and a statistically significant increase in the INR, after 3 months of treatment. In addition, AFP was significantly lower after 3 months of treatment. There was no statistically significant change in telomere length after 3 months of treatment, as shown in Table 5. Figure 3A shows AFP level before and after treatment in the HCC group, and Figure 3B shows telomere length before and after treatment in the HCC group.

| Variables | Before | After | Change | P value | |

| INR | mean ± SD | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.0211,3 |

| Range | 1.0-1.7 | 1.0-1.6 | -0.3 to 0.5 | ||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | mean ± SD | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | 0.0841 |

| Range | 0.2-2.1 | 0.4-2.2 | -1.3 to 1.1 | ||

| Albumin (g/dL) | mean ± SD | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 3.4 ± 0.4 | -0.4 ± 0.4 | < 0.0011,3 |

| Range | 2.8-4.8 | 2.7-4.3 | -1.2 to 0.3 | ||

| ALT (U/L) | mean ± SD | 28.1 ± 15.4 | 24.1 ± 15.3 | -4.0 ± 16.9 | 0.2011 |

| Range | 6.0-76.0 | 9.0-70.0 | -62.0 to 43.0 | ||

| AST (U/L) | mean ± SD | 43.8 ± 26.5 | 38.2 ± 16.8 | -5.6 ± 21.9 | 0.1721 |

| Range | 10.0-140.0 | 21.0-110.0 | -86.0 to 21.0 | ||

| AFP (ng/mL) | Median (1st-3rd IQ) | 31.5 (6.2-235.0) | 11.5 (4.2-101.0) | -14.9 (-192.0 to -1.9) | < 0.0012,3 |

| Range | 0.9-800.0 | 0.8-388.0 | -456.0 to 2.9 | ||

| Telomere length (× 103) | Median (1st-3rd IQ) | 1.3 (1.0-1.8) | 1.6 (1.0-1.9) | 0.3 (-0.8 to 0.8) | 0.5042 |

| Range | 0.5-3.5 | 0.6-5.3 | -1.8 to 4.3 | ||

Despite a higher level of AFP in the HCC group before treatment, there were no statistically significant differences between the CLD and HCC groups before and after treatment. There was also no statistically significant difference between the CLD and HCC groups before and after treatment (Table 6). Figure 3C shows AFP level before and after treatment in the HCC and CLD groups. Figure 3D shows telomere length before and after treatment in the HCC and CLD groups.

| Variables | HCC group (total = 30) | CLD group (total = 30) | P value | |||

| Before | After | Before | After | |||

| AFP (ng/mL) | Median (1st-3rd IQ) | 31.5 (6.2-235.0) | 11.5 (4.2-101.0) | 11.5 (4.2-101.0) | 0.198 | 0.999 |

| Range | 0.9-800.0 | 0.8-388.0 | 0.8-388.0 | |||

| Telomere length (× 103) | Median (1st-3rd IQ) | 1.3 (1.0-1.8) | 1.6 (1.0-1.9) | 1.4 (1.1-1.9) | 0.626 | 0.647 |

| Range | 0.5-3.5 | 0.6-5.3 | 0.4-7.6 | |||

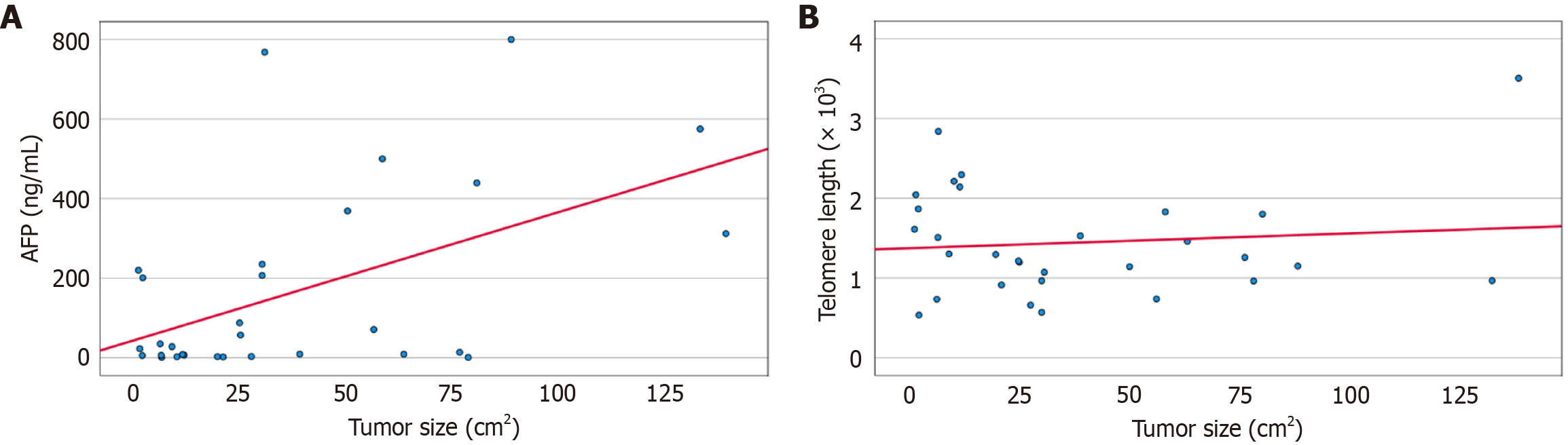

AFP in the HCC group before treatment had a statistically significant positive correlation with tumor size. There were no statistically significant correlations between AFP, and age, scores or telomere length (Table 7).

| AFP with variables | HCC group (total = 30) | CLD group (total = 30) | |||

| Before | After | Change | |||

| Age (years) | r value | -0.110 | 0.000 | ||

| P value | 0.561 | 0.999 | |||

| Telomere length (× 103) | r value | -0.182 | 0.147 | -0.196 | 0.084 |

| P value | 0.335 | 0.437 | 0.298 | 0.659 | |

| MELD score | r value | 0.304 | 0.349 | 0.005 | 0.150 |

| P value | 0.102 | 0.059 | 0.978 | 0.430 | |

| Child-Pugh score | r value | 0.214 | 0.350 | -0.163 | 0.046 |

| P value | 0.257 | 0.058 | 0.390 | 0.809 | |

| Tumor size (cm2) | r value | 0.422 | 0.112 | 0.209 | |

| P value | 0.021 | 0.703 | 0.474 | ||

With regard to age, Child-Pugh, and MELD scores, there were no statistically significant correlations between telomere length, age, and both scores before and after 3 months of treatment in the HCC and CLD groups. There was also no statistically significant correlation between telomere length and tumor size before and after 3 months of treatment in the HCC group (Table 8). Figure 4A shows the correlation between AFP before treatment, and tumor size in the HCC group. Figure 4B shows the correlation between telomere length after treatment and tumor size in the HCC group.

| Telomere length with variables | HCC group (total = 30) | CLD group (total = 30) | |||

| Before | After | Change | |||

| Age (years) | r value | -0.100 | -0.047 | ||

| P value | 0.599 | 0.805 | |||

| MELD score | r value | -0.027 | -0.130 | 0.074 | -0.174 |

| P value | 0.887 | 0.493 | 0.696 | 0.357 | |

| Child-Pugh score | r value | -0.027 | 0.028 | -0.129 | 0.182 |

| P value | 0.888 | 0.882 | 0.496 | 0.335 | |

| Tumor size (cm2) | r value | -0.157 | 0.130 | 0.292 | |

| P value | 0.408 | 0.659 | 0.311 | ||

Table 9 shows that, HCC cases with a complete response had significantly higher AFP before treatment, while after treatment they had significantly lower AFP. With regard to telomere length, there was no statistically significant difference between patients with a complete and partial response. Figure 5A compares AFP before and after treatment according to response in the HCC group. Figure 5B compares telomere length before and after treatment according to response in the HCC group. Partial and complete response were defined according to the modified RECIST criteria, where complete response denotes the disappearance of arterial enhancement while a partial response denotes at least a 30% decrease in arterial enhancement of the sum of diameters of the lesions[19].

| Variables | Response | P value | ||

| Complete (total = 16) | Partial (total = 14) | |||

| AFP (ng/mL) | Before | 57.6 (4.5-72.4) | 291.2 (9.1-500.0) | 0.028a |

| After | 11.5 (3.3-16.0) | 147.4 (8.4-283.0) | 0.011a | |

| Change | -46.1 (-48.4 to -0.5) | -143.8 (-206.3 to 2.1) | 0.119 | |

| Telomere length (× 103) | Before | 1.5 (0.9-2.1) | 1.4 (1.0-1.5) | 0.480 |

| After | 1.8 (0.8-2.0) | 1.6 (1.1-1.9) | 0.318 | |

| Change | 0.3 (-1.1 to 0.8) | 0.3 (-0.2 to 0.8) | 0.454 | |

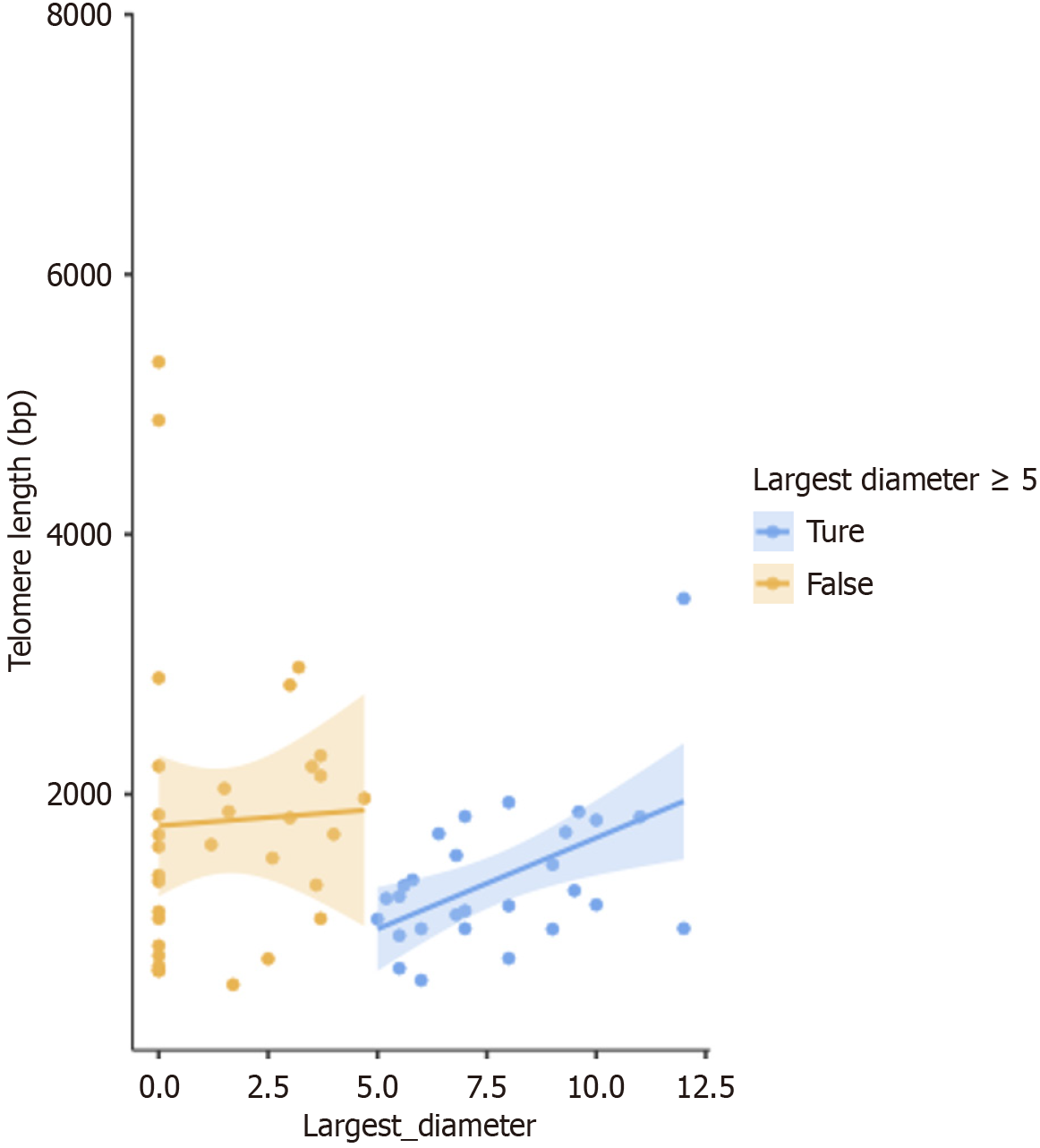

Figure 6 shows a scatter plot of the relationship between telomere length and largest diameter of HFLs for all patients in the HCC group before and after treatment. The measures were classified to 2 groups with a cutoff value of the largest diameter of 5 cm, and a linear regression was plotted for each one in the two groups. The shaded area around the regression line shows the standard error. For all telomere lengths measured in the HCC group both before and after treatment, choosing a cutoff of tumor length of 5 cm signified an advanced local HCC, with no vascular invasion or metastasis, as indicated by radiology. For tumors ≥ 5 cm, there was a statistically significant positive correlation between the HFL largest diameter and telomere length, with a P value = 0.025, and Spearman’s Rho = 0.422. For non-advanced HCC < 5 cm in diameter (largest size), there was no statistically significant correlation. We found a positive Spearman's rank correlation between telomere length and tumor size in the ≥ 5 cm group, P value = 0.025. There were 28 samples in the ≥ 5 cm group, including pre- and post-treatment data, with one patient with an exact 5 cm tumor post-intervention, and none at the baseline (pre-intervention). This cut-off was chosen according to a recent report by Kim et al[20], which proposed a new classification system for tumors ≥ 5 cm (shown in Supplementary Table 1).

Table 10 shows that diabetes mellitus and male sex were significant factors in increased telomere length in the HCC group, this model could explain 84.5% of telomere length variability in the HCC group. No significant model was obtained in the CLD group.

| Factors | Regression coefficient (β) | SE | P value | 95%CI | R2 |

| DM | 0.477 | 0.174 | 0.011 | 0.120-0.833 | 0.845 |

| Male sex | 0.641 | 0.246 | 0.015 | 0.137-1.145 |

Table 1 shows that by dividing the HCC group according to tumor size with a cutoff of 5 cm, and performing the Mann-Whitney test it was found that, at baseline telomere length was significantly lower in cases with tumor size ≥ 5 cm, than in those with tumor size < 5 cm (30 patients; P value = 0.03). This means that telomere length was significantly lower among cases with tumor size ≥ 5 cm.

Supplementary Figure 1 shows that telomere length had no significant diagnostic performance in predicting complete response (AUC = 0.576, P value = 0.480, cut point ≥ 1.9 × 103, sensitivity = 37.5%, specificity = 92.8%).

Prior to registering the protocol of this study with the ethical committee, there had only been two retrospective cohort studies on the effect of TACE on telomere length[21,22]. According to an earlier study by Plentz et al[16] in 2004, they found that cancerous hepatocytes showed shorter telomere length than the surrounding regenerative non-cancerous hepatocyte cirrhotic nodules; this study did not include healthy controls. In addition, another study by Yang et al[23] in 2016 examined the prognostic effect of telomeres in tumor tissue, vs adjacent cirrhotic non-tumor tissue, and found that longer telomere length tended to occur in advanced tumors. In a study comparing HCC patients with healthy-matched controls, it was found that HCC patients had shorter telomere length in the 5-year period prior to diagnosis[24]. Another retrospective cohort study in patients undergoing TACE did not include a control group[21]. Thus, our study is the first registered (in 2020) protocol of a prospective cohort study on the follow-up of TACE and RF patients in relation to the short-term (3 months) effect of telomeres in peripheral lymphatic cells on HCC prognosis and diagnosis.

In studies on HCC and telomere length, there are two main approaches, either using peripheral leukocytes, or hepatocytes from pathology samples following partial resection, or complete surgical excision of the liver[24,25]. In our study, we measured leukocytic telomere length in peripheral blood samples of both a cirrhotic and HCC group at baseline and in the HCC group three months after loco-regional therapy, using a qPCR method.

A statistically significant difference in leucocytic telomere length was not found between the CLD and HCC groups at baseline. This is in accordance with Zeng et al[24], who performed a case-control study, and examined 268 HCC patients with 536 randomly selected matched controls, and found a slight shortening of telomere length in leukocytes from HCC patients compared to the controls, which did not reach statistical significance. In addition, a study on liver histology samples obtained by fine needle aspiration cytology from 58 HCC patients and 17 chronic hepatitis patients, showed that telomere length, although slightly shorter in the HCC group, was statistically insignificant[26]. Rahamtalla et al[27], who compared telomere length in 113 patients with HCC or CLD and 50 healthy controls, found that telomere length was significantly shorter in the HCC group than in the healthy controls, but not significantly different when compared to the CLD group[27]. This non-significant relationship between telomere length in cirrhosis and HCC could be attributed to their shared underlying pathological pathway of chronic liver injury (which causes telomere shortening in both cirrhosis and early HCC), or to the limitations of peripheral leukocyte telomere length, as a surrogate for hepatic tissue telomere length.

In addition, we found no significant difference between telomere length in the HCC group before and after treatment (3 months after loco-regional therapy). However, on dividing the HCC group according to tumor size, with a cutoff value of 5 cm, and performing the Mann-Whitney test, we found that telomere length was significantly shorter in cases with tumor size ≥ 5 cm, than in cases with tumor size < 5 cm (total of 30 patients; P value = 0.03). We used this cutoff (5 cm) as suggested by a recent study as a new BCLC classification, based on the size of the tumor. Kim et al[20], proposed a new BCLC classification for a single tumor ≥ 5 cm in size. The study included 3965 HCC patients with BCLC class A and B, and a newly designed group they created named group X (i.e., BCLC group A with tumor size ≥ 5 cm). They found that the overall survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years in group X were similar to those with BCLC class B, and worse than BCLC class A with tumors < 5 cm.

A study by Ma et al[28], showed that cancer associated fibroblasts (CAF) in the HCC tissue exhibit shorter telomeres as compared to the surrounding non-cancerous tissue. Moreover, overall survival was worst when both the tumor cells and CAF had short telomeres, and vice versa, survival was best when both had long telomere length. Moreover, a study on liver tissue, using the quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridization (Q-FISH) technique, showed that in advanced stages, telomerase activity was not correlated with tumor size or telomere length, while in smaller tumors < 5 cm telomerase activity was reversely related to telomere length[25].

However, a study performed by Liu et al[29] contradict our results, where the telomere length in leukocytes was longer in the HCC group, as compared to the CLD group and healthy controls. Also, there was no statistical relationship between tumor size, or stage, and telomere length. A possible explanation for this is higher telomerase activity in those tumors related to ethnicity, and HBV was the only cause of HCC in this study. Also, heterogeneity in tumor growth, previous surgeries, or tumor storage and thawing for histopathology could result in high variability of the biomarker[29].

A review by Carulli and Anzivino[11] found that the degree of telomere shortening was correlated with the accumulated aging of hepatocytes (senescence), and the degree of liver cirrhosis. Also, telomere shortening was greater in cirrhosis than in chronic hepatitis. Telomerase is reactivated in 90% of all human tumors. As telomerase activity is absent in adult liver, telomere length is shortened in liver cirrhosis, and inflammation due to replication; however, telomerase activity is increased in HCC due to reactivation in 80% of HCC. Thus, in theory, telomere length should elongate with increased telomerase activity; however, rapid cellular tumor replication will hide this increased activity. In addition, several studies has shown telomere shortening in HCC, especially aneuploid type HCC as opposed to diploid type HCC[30].

On examining the whole data sample of the HCC group, before and after treatment, a positive Spearman rank correlation was found between telomere length, and tumor size in the “≥ 5 cm subgroup” only (28 samples-including both before and after the intervention from a total of 60 samples), P value = 0.025. In the “< 5 cm subgroup”, there was no statistically significant correlation with telomere length (Figure 6).

Yang et al[23] performed a study on 126 tumor and non-tumor liver tissue from HCC patients, with available patient survival data from the United States, and found that telomere length did not affect survival or mortality, but longer telomere length was associated with advanced tumors. Another study, showed that poorer survival during a follow up period of 4-42 months occurred with increased telomerase activity, and increased telomere length, in advanced HCC liver tissue[31]. In a study by Kojima et al[32], it was found that telomerase enzyme activity in tumor tissue was higher than that in non-tumor tissue. This was combined with a tendency for telomere length elongation, as telomerase activity increased. Moreover, another study on 250 HCC patients receiving TACE, found that longer telomere length in peripheral leukocytes, and lower mitochondrial DNA copy number are indicators for poorer overall survival[21].

Longer telomere length is linked to advanced cancers due to higher proliferation, cellular immortality of the cancer cells, and by activation of the “telomere maintenance mechanisms”. Thus, preventing the “telomere crisis” is caused by excessive shorting of telomeres in tumor cells, and the cancer transforming from early to advanced stage. Cells with longer telomeres have higher chromosomal instability, and nuclear atypia[33]. An example of immortal cells, with elongated telomeres, and highly active telomerase, are the commercially available HeLa cells[34].

At odds with our study findings, Liu et al[22], who examined the effect of telomere length in predicting TACE prognosis in 269 patients with HCC in two cohorts from two different hospitals, found by using Kaplan Meier analysis, that overall survival (follow up 50 weeks) was higher in those with a longer telomere length, after TACE. Moreover, a study by Yang et al[10] on European and Asian populations, found that there was no linear correlation between hereditary telomere length and HCC. They chose specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for each population that had relationships with variable risk factors for HCC: 9 SNPs for Asians, and 98 SNPs for Europeans.

DNA loses a small portion of the telomere with each cellular division, and as telomeres are limited in length by the cellular limitation of DNA replication, thus it shortens with aging. There are other factors that increase the attrition rate of telomeres including oxidative stress, in addition to, replication stress. Telomerase enzyme can elongate telomeres and increase the ability for cellular replication, but it is normally inhibited in somatic cells, as it may increase the cancer risk by uncontrolled DNA replication[35]. TERT promoter gene mutation is the most common mutation associated with HCC[36]. TERT is very common in cancer cells, with more than 90% of human cancers showing re-expression of the gene, resulting in increased enzyme activity, and immortality in the cells[37]. A recent mini-review by Umar Liman et al[38], on the effect of TERT promoter mutations on non-alcoholic steatohepatitis-related HCC found that the two SNPs most incorporated in the upregulation of TERT gene expression are C228T and C250T. There are reported missense mutations in the genes TERT and TERC in liver cirrhosis patients, more than the controls[11]. In cancers originating from stem cells, TERT promotor mutations are usually absent, while in cells with low proliferation such as hepatocytes, brain cells, melanocytes, etc., TERT promoter mutations are present[39]. Moreover, TERT promoter mutations are rare in highly replicative cellular cancers such as in the intestine and blood. The low telomere level in TERT promoter mutated cancer is mostly a late occurrence after telomere exhaustion by the growing cancer; however, in HCC the mutation occurs at earlier stages of the tumor[40]. Ningarhari et al[14], examined the relationship between telomere length, TERT alteration and expression, in HCC patients. They found that TERT “oncogene addiction” (where the HCC depends on TERT oncogene reactivation for its survival) can be a target for HCC treatment, through anti-TERT antisense oligonucleotide treatment. Unfortunately, most of the research carried out on reducing telomere shortening, is aimed at decreasing the effects of age-related diseases, not cancer therapy. This is despite the fact that, aging is a complete degenerative process that protects the cells[12].

Moreover, we did not find statistically significant correlations between telomere length and the following parameters: Age, AFP, and clinical scores in the HCC and CLD groups, or tumor size in the HCC group. However, AFP in the HCC group before treatment had a statistically significant positive correlation with tumor size.

In our study there was no statistically significant relationship between telomere length and the Child-Pugh or MELD scores in the HCC or CLD group. In comparison, a study by Jiao et al[36], found that the Child-Pugh score had no statistically significant relationship with the mutated and un-mutated TERT promoter gene, in a cohort of 218 HCC patients. This could be explained by both cohorts already having diseased liver cells and cirrhosis, despite the difference in clinical scores.

Our study results were similar to those by Zeng et al[24], as no statistically significant relationship between age and telomere length was found. However, Rahamtalla et al[27], demonstrated that telomere length was shorter in younger patients (35-50, and 51-66 years), when compared with older patients (67-82 years). This could be explained by the relatively narrow age range in our study population (50-78 years for HCC, 49-86 years for cirrhosis) or the short follow-up period (3 months), which may not capture age-related telomere length changes that manifest over longer durations.

HCC is considered the most common malignancy in males in Egypt, and the second most common in females. In a study of 300 HCC patients in Egypt, it was found that males constitute 81.5%, while females constitute 18.5%[41]. In another study of 497 HCC Egyptian patients, males constituded 88% and females 12%[42]. In our study males were more predominant in the HCC group (n = 27 vs n = 3).

We performed a multivariate regression analysis which showed that, diabetes mellitus, and male sex were significant factors in increased telomere length in the HCC group, with no significant model for the CLD group.

We did not include C-reactive protein (CRP) in our inflammatory markers, as CRP is a non-specific inflammatory marker and was found to have the highest odds ratio in patients with HCC and portal vein thrombosis[43].

We excluded patients who took DAAs in the last 12 months, as at the time of submitting our protocol, there was a debate about the role of DAAs in initiating HCC tumors, or increasing its severity[44,45]. It was subsequently proven by multiple meta-analyses and systematic reviews that there was no relationship[46].

We acknowledge several limitations in our study. First, the cause-and-effect link between telomeres and both liver cirrhosis and HCC could not be clarified. To overcome this, a longitudinal study must be planned to determine the exact pathophysiology of telomeres in HCC. Second, our follow-up period was short (3 months post-intervention), with a small sample size. Third, we did not have the resources or funds to explore telomerase enzyme activity or genetics (such as TRAP assay, or TERT promoter mutations (e.g., C228T/C250T)), or verify our telomerase length quantification using multiple synchronous methods, such as the Q-FISH technique. Also, we could not include healthy controls for the same reason. Finally, the male predominance in our HCC group limited our ability to conduct more research on the role of gender variability in relation to telomere length and HCC outcome.

We conclude that in patients with HCC, the leukocytic telomere length could be a good surrogate for tumor activity, as compared to other tissue markers. Further research should include the following: Telomerase activity and TERT promoter mutations in a larger cohort and including a healthy group for validation of the results and subsequent use in clinical practice. Leukocytic telomere length shows promise as a surrogate for tumor activity in HCC patients with tumor size

We thank Mohamed El-Nakeep MSc for his expert revision, and modifications of the biostatistics in this study.

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68227] [Article Influence: 13645.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (201)] |

| 2. | Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Mathers C, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Bray F. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:1941-1953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3585] [Cited by in RCA: 5031] [Article Influence: 628.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, Ferrer-Fàbrega J, Burrel M, Garcia-Criado Á, Kelley RK, Galle PR, Mazzaferro V, Salem R, Sangro B, Singal AG, Vogel A, Fuster J, Ayuso C, Bruix J. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J Hepatol. 2022;76:681-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1904] [Cited by in RCA: 3070] [Article Influence: 767.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (61)] |

| 4. | Mulyadi R, Hasan I, Sidipratomo P, Putri PP. Prognosis of transarterial chemoembolization-sorafenib compared to transarterial chemoembolization-alone in hepatocellular carcinoma stage C: a systematic review. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2024;36:18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Creighton HB, McClintock B. A Correlation of Cytological and Genetical Crossing-Over in Zea Mays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1931;17:492-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Muller H. The remaking of chromosomes. Collecting Net. 1938;8:182-198. |

| 7. | Armanios M. The Role of Telomeres in Human Disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2022;23:363-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lansdorp PM. Telomeres, aging, and cancer: the big picture. Blood. 2022;139:813-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Aksenova AY, Mirkin SM. At the Beginning of the End and in the Middle of the Beginning: Structure and Maintenance of Telomeric DNA Repeats and Interstitial Telomeric Sequences. Genes (Basel). 2019;10:118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yang C, Wu X, Chen S, Xiang B. Association between telomere length and hepatocellular carcinoma risk: A Mendelian randomization study. Cancer Med. 2023;12:9937-9944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Carulli L, Anzivino C. Telomere and telomerase in chronic liver disease and hepatocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6287-6292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schellnegger M, Hofmann E, Carnieletto M, Kamolz LP. Unlocking longevity: the role of telomeres and its targeting interventions. Front Aging. 2024;5:1339317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Xie JW, Wang HL, Lin LQ, Guo YF, Wang M, Zhu XZ, Niu JJ, Lin LR. Telomere-methylation genes: Novel prognostic biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2025;49:102516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ningarhari M, Caruso S, Hirsch TZ, Bayard Q, Franconi A, Védie AL, Noblet B, Blanc JF, Amaddeo G, Ganne N, Ziol M, Paradis V, Guettier C, Calderaro J, Morcrette G, Kim Y, MacLeod AR, Nault JC, Rebouissou S, Zucman-Rossi J. Telomere length is key to hepatocellular carcinoma diversity and telomerase addiction is an actionable therapeutic target. J Hepatol. 2021;74:1155-1166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Li HY, Zheng LL, Hu N, Wang ZH, Tao CC, Wang YR, Liu Y, Aizimuaji Z, Wang HW, Zheng RQ, Xiao T, Rong WQ. Telomerase-related advances in hepatocellular carcinoma: A bibliometric and visual analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:1224-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 16. | Plentz RR, Caselitz M, Bleck JS, Gebel M, Flemming P, Kubicka S, Manns MP, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular telomere shortening correlates with chromosomal instability and the development of human hepatoma. Hepatology. 2004;40:80-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2447] [Cited by in RCA: 2857] [Article Influence: 119.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cawthon RM. Telomere length measurement by a novel monochrome multiplex quantitative PCR method. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 925] [Cited by in RCA: 1144] [Article Influence: 67.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Arora A, Kumar A. Treatment Response Evaluation and Follow-up in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;4:S126-S129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim HS, Choi SJN, Lee HK; Korean Liver Cancer Association. Proper position of single and large (≥5 cm) hepatocellular carcinoma in Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer classification. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e34639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bao D, Ba Y, Zhou F, Zhao J, Yang Q, Ge N, Guo X, Wu Z, Zhang H, Yang H, Wan S, Xing J. Alterations of telomere length and mtDNA copy number are associated with overall survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with transarterial chemoembolization. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;78:791-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu HQ, An JZ, Liu J, Yang YF, Zhang HX, Zhao BY, Li JB, Yang HS, Chen ZN, Xing JL. Leukocyte telomere length predicts overall survival in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1040-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yang B, Shebl FM, Sternberg LR, Warner AC, Kleiner DE, Edelman DC, Gomez A, Dagnall CL, Hicks BD, Altekruse SF, Hernandez BY, Lynch CF, Meltzer PS, McGlynn KA. Telomere Length and Survival of Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the United States. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zeng H, Wu HC, Wang Q, Yang HI, Chen CJ, Santella RM, Shen J. Telomere Length and Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Nested Case-control Study in Taiwan Cancer Screening Program Cohort. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:637-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nakajima T, Katagishi T, Moriguchi M, Sekoguchi S, Nishikawa T, Takashima H, Watanabe T, Kimura H, Minami M, Itoh Y, Kagawa K, Okanoue T. Tumor size-independence of telomere length indicates an aggressive feature of HCC. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;325:1131-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Saini N, Chawla Y, Sharma S, Duseja A, Das R, Rajvanshi A. Comparison of Telomere Length in Chronic Hepatitis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cases with Cirrhosis and without Cirrhosis: 359. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:S163. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Rahamtalla FA, Shammat IM, Mudawi SBM, Abbas M, Kheir Elsid MAH, Abdalla MSM. Short Telomere Length in Plasma of Sudanese Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Chronic Liver Diseases. Sudan J Med Sci. 2024;19:460-472. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Ma LJ, Wang XY, Duan M, Liu LZ, Shi JY, Dong LQ, Yang LX, Wang ZC, Ding ZB, Ke AW, Cao Y, Zhang XM, Zhou J, Fan J, Gao Q. Telomere length variation in tumor cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts: potential biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Pathol. 2017;243:407-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Liu J, Yang Y, Zhang H, Zhao S, Liu H, Ge N, Yang H, Xing JL, Chen Z. Longer leukocyte telomere length predicts increased risk of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a case-control analysis. Cancer. 2011;117:4247-4256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | In der Stroth L, Tharehalli U, Günes C, Lechel A. Telomeres and Telomerase in the Development of Liver Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:2048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Oh BK, Kim H, Park YN, Yoo JE, Choi J, Kim KS, Lee JJ, Park C. High telomerase activity and long telomeres in advanced hepatocellular carcinomas with poor prognosis. Lab Invest. 2008;88:144-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kojima H, Yokosuka O, Imazeki F, Saisho H, Omata M. Telomerase activity and telomere length in hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:493-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Matsuda Y, Ye J, Yamakawa K, Mukai Y, Azuma K, Wu L, Masutomi K, Yamashita T, Daigo Y, Miyagi Y, Yokose T, Oshima T, Ito H, Morinaga S, Kishida T, Minamoto T, Kojima M, Kaneko S, Haba R, Kontani K, Kanaji N, Okano K, Muto-Ishizuka M, Yokohira M, Saoo K, Imaida K, Suizu F. Association of longer telomere length in cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts with worse prognosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2023;115:208-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ivanković M, Cukusić A, Gotić I, Skrobot N, Matijasić M, Polancec D, Rubelj I. Telomerase activity in HeLa cervical carcinoma cell line proliferation. Biogerontology. 2007;8:163-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Srinivas N, Rachakonda S, Kumar R. Telomeres and Telomere Length: A General Overview. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Jiao J, Watt GP, Stevenson HL, Calderone TL, Fisher-Hoch SP, Ye Y, Wu X, Vierling JM, Beretta L. Telomerase reverse transcriptase mutations in plasma DNA in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma or cirrhosis: Prevalence and risk factors. Hepatol Commun. 2018;2:718-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Colebatch AJ, Dobrovic A, Cooper WA. TERT gene: its function and dysregulation in cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2019;72:281-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Umar Liman U, Hawage AS, De Silva S, Samarasinghe SM, Tennekoon KH, Siriwardana RC, Niriella MA. Pathogenic effects of telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutations in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and its potentials as a diagnostic biomarker. Egypt J Med Hum Genet. 2025;26:111. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 39. | Bell RJ, Rube HT, Xavier-Magalhães A, Costa BM, Mancini A, Song JS, Costello JF. Understanding TERT Promoter Mutations: A Common Path to Immortality. Mol Cancer Res. 2016;14:315-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Lorbeer FK, Hockemeyer D. TERT promoter mutations and telomeres during tumorigenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2020;60:56-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Elghazaly H, Gaballah A, Bahie Eldin N. Clinic-pathological pattern of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in Egypt. Ann Oncol. 2018;29 Suppl 5:v5-v6. |

| 42. | Ali AAK, Gamal SE, Anwar R, Elzahaf E, Eskandere D. Assessment of clinico-epidemiological profile of Hepatocellular carcinoma in the last two decades. Egypt J Intern Med. 2023;35:18. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Carr BI, Akkiz H, Guerra V, Üsküdar O, Kuran S, Karaoğullarından Ü, Tokmak S, Ballı T, Ülkü A, Akçam T, Delik A, Arslan B, Doran F, Yalçın K, Altntaş E, Özakyol A, Yücesoy M, Bahçeci Hİ, Polat KY, Ekinci N, Şimşek H, Örmeci N, Sonsuz A, Demir M, Kılıç M, Uygun A, Demir A, Yilmaz S, Tokat Y. C-reactive protein and hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of its relationships to tumor factors. Clin Pract (Lond). 2018;15:625-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Reig M, Mariño Z, Perelló C, Iñarrairaegui M, Ribeiro A, Lens S, Díaz A, Vilana R, Darnell A, Varela M, Sangro B, Calleja JL, Forns X, Bruix J. Unexpected high rate of early tumor recurrence in patients with HCV-related HCC undergoing interferon-free therapy. J Hepatol. 2016;65:719-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 725] [Cited by in RCA: 816] [Article Influence: 81.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Muzica CM, Stanciu C, Huiban L, Singeap AM, Sfarti C, Zenovia S, Cojocariu C, Trifan A. Hepatocellular carcinoma after direct-acting antiviral hepatitis C virus therapy: A debate near the end. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:6770-6781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Celsa C, Stornello C, Giuffrida P, Giacchetto CM, Grova M, Rancatore G, Pitrone C, Di Marco V, Cammà C, Cabibbo G. Direct-acting antiviral agents and risk of Hepatocellular carcinoma: Critical appraisal of the evidence. Ann Hepatol. 2022;27 Suppl 1:100568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |