Published online Dec 14, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i46.113172

Revised: September 9, 2025

Accepted: October 27, 2025

Published online: December 14, 2025

Processing time: 115 Days and 1.5 Hours

The diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) involves clinical, endoscopic, and radiologic evaluation. Endoscopic procedures, particularly in pediatrics, re

To investigate whether serum biomarkers can differentiate between pediatric pa

Pediatric patients undergoing diagnostic colonoscopy at British Columbia Chil

The study included 246 pediatric patients, who had a median age of 13.03 years and were 37.4% female (103 CD, 52 UC, 91 controls). In univariate analyses, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9) was the only biomarker sig

Serum biomarkers, particularly CXCL9, IL-8, and IL-22, can aid in the diagnosis of pediatric IBD. CXCL9 and IL18 were found to be significant predictors of CD, and CXCL1 differed between patients requiring biologic therapy vs those who did not.

Core Tip: The diagnosis of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) usually requires invasive endoscopy under anesthesia, which carries risks in children. In this study, we evaluated serum cytokines as potential non-invasive biomarkers to distinguish pediatric IBD from non-IBD controls. Among over 250 pediatric patients, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9), interleukin 8 (IL-8), and IL-22 emerged as key markers with strong discriminatory capacity. CXCL9 and IL-18 differentiated Crohn’s disease from ulcerative colitis, whereas CXCL1 levels were associated with the need for biologic the

- Citation: Eindor-Abarbanel A, Tsai K, Sandhu A, Vallance B, Jacobson K. Serum C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9, interleukin 8, and interleukin 22 as key biomarkers in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(46): 113172

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i46/113172.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i46.113172

The current gold standard for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is based on clinical and endoscopic evaluation as well as histologic and radiologic evaluation[1]. However, endoscopic evaluation can be uncomfortable and carry some risks, especially in the pediatric population that requires general anesthesia to perform the procedure[2].

Classic inflammatory biomarkers such as hemoglobin, C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and albumin are part of the diagnostic approach for IBD. In clinical practice, these biomarkers are commonly utilized; how

In the realm of contemporary research of IBD, various biomarkers have undergone evaluation and analysis over the past two decades, remaining integral to ongoing clinical research[7,8]. During this period, the proposition of a regulatory cytokine network with significant implications for IBD progression has gained increasing prominence. Cytokines, encom

Recently, a limited number of cytokines known to play crucial roles in the IBD have been explored as potential key biomarkers for diagnosing IBD[13-16]. However, there is a notable scarcity of studies focused on cytokine levels in pa

Our objective was to explore the potential of serum biomarkers in distinguishing between pediatric patients with and without IBD. Additionally, we identified biomarkers that could differentiate between CD and UC, and correlate with di

Pediatric patients undergoing their first diagnostic colonoscopy at British Columbia Children's Hospital (Vancouver, BC, Canada) between December 2017 and June 2022 were invited to participate in the study.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Pediatric patients (ages 7-18 years) undergoing their first diagnostic colonoscopy; and (2) Patients diagnosed with IBD and non-IBD controls (e.g., functional abdominal pain, irritable bowel syndrome, polyps, infection or other inflammatory disease).

Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients with an inconclusive diagnosis following colonoscopy and histopathology; (2) Patients who had previously undergone colonoscopy or had prior established IBD diagnosis; or (3) Patients who were not within the above age range.

A 2 mL blood sample was collected from each participant at the time of colonoscopy. Demographic and clinical data were retrieved for all patients. The initial analysis included 95 samples, which were evaluated using LegendplexTM flow cyto

Based on an initial screening and extensive literature review, a refined panel of 12 serum biomarkers was selected for further investigation (see Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 for the biomarker list and initial analysis results). A customized LegendplexTM flow cytometry kit was then designed to specifically measure these 12 bio

| Biomarker | IBD (n = 155) | Non-IBD (n = 91) | P value |

| CCL2 | 101 ± 42.9 | 108 ± 43.7 | 0.239 |

| CCL5 | 1650 ± 1010 | 1710 ± 665 | 0.526 |

| CCL7 | 249 ± 135 | 244 ± 120 | 0.761 |

| IL-8 | 27.1 ± 151 | 8.93 ± 4.63 | 0.138 |

| TSLP | 269 ± 123 | 265 ± 132 | 0.812 |

| CCL3 | 45.6 ± 15.7 | 44.0 ± 13.1 | 0.409 |

| CXCL1 | 347 ± 289 | 306 ± 275 | 0.267 |

| CXCL2 | 200 ± 197 | 196 ± 225 | 0.892 |

| CXCL9 | 3980 ± 3250 | 1440 ± 1460 | < 0.001 |

| IL-18 | 169 ± 187 | 134 ± 216 | 0.204 |

| IL-22 | 52.8 ± 163 | 31.9 ± 13.6 | 0.113 |

| TARC | 326 ± 461 | 331 ± 241 | 0.913 |

Blood samples were analyzed using the customized LegendplexTM kit, and a supervised learning model was developed to assess its predictive ability regarding the following outcome measures: (1) Differentiation between IBD and non-IBD; (2) Distinction between CD and UC among patients with IBD; and (3) Prediction of disease progression. For prognostic analysis of treatment escalation, we defined a “favorable outcome” as remaining both steroid-free and biologic-free at the 1-year follow-up. This definition was based on medication use data recorded in the medical chart: Being steroid-free within 1 year of diagnosis without requiring biologic therapy vs those who required biologic treatment.

The study was approved by the British Columbia Children’s Hospital ethics committee (Approval No. H10-01760). All parents or legal guardians of participants signed an informed consent. The manuscript was written according to the STROBE Statement checklist of items.

All analyses were conducted in R (v4.2.2) using the tidymodels ecosystem. Two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Continuous variables are summarized as median (interquartile range) and categorical variables as count (percentage). Groupwise comparisons of biomarker expression were performed using Student’s t-tests.

To identify biomarkers associated with IBD status, we fit separate logistic regression models for each analyte, adjusting for age, sex, and ethnicity. From each model, we extracted the type II Wald χ2 statistic for the biomarker term. Percentile bootstrap resampling (5000 replicates) was used to derive P values and confidence intervals.

We then trained a random forest classifier (1000 trees) using the ranger engine. The number of variables sampled at each split (mtry) and the minimum node size (min_n) were tuned via grid search. Model training and evaluation used 5-fold cross-validation repeated 10 times, stratified by diagnosis. Final performance was assessed on held-out folds, pre

Secondary outcomes were analyzed analogously, using t-tests for expression differences, bootstrap-ranked χ2 scree

We initially performed an exploratory screen of 50 biomarkers to identify useful candidates for further study in a subset of 95 patients with IBD (n = 54) and without-IBD (n = 41). The median age of participants was 13.4 years, and 39 (41%) were female. In the initial subset, five biomarkers, namely C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9, MIG), CXCL1, thy

A total of 255 pediatric patients were recruited to the study, of whom 9 were excluded due to inconclusive diagnosis, leaving 246 pediatric patients for the analyses. The median age of participants was 13.03 years, and 92 (37.4%) were female. IBD was diagnosed in 155 patients (63.0%), with 103 (66.4%) classified as having CD (Table 2). Comparison of biomarker concentrations between IBD and nonIBD control subjects revealed that CXCL9 was significantly elevated in IBD (mean 3980 ± 3250 pg/mL vs 1440 ± 1460 pg/mL in controls; P < 0.001). IL22 and IL8 were higher in IBD (means of 52.8 ± 16.3 pg/mL and 27.1 ± 151 pg/mL, respectively) compared with controls (31.9 ± 13.6 pg/mL and 8.93 ± 4.63 pg/mL), but the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.113 and P = 0.138, respectively). Other analytes showed no significant differences (Table 1).

| All (n = 246) | IBD (n = 155) | Non-IBD (n = 91) | |

| Age at diagnosis median (IQR; year) | 11.63 (8.56-13.95) | 11.15 (9.17-15.08) | 11.68 (8.48-13.83) |

| Female | 44 (34.37) | 10 (35.71) | 34 (34) |

| Crohn's disease | 103 (41.9) | 103 (66.4) | 0 |

| UC | 46 (18.7) | 46 (29.7) | 0 |

| IBD-U | 6 (2.4) | 6 (3.9) | 0 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Western European | 175 (71.1) | 106 (68.4) | 69 (75.8) |

| South Asian | 32 (13) | 22 (14.2) | 10 (10.9) |

| Other | 39 (15.8) | 27(17.4) | 12 (13.2) |

| Biologic treatment at 1 year | 48 (39) | ||

| Activity score at diagnosis | |||

| Remission | 4 (2.58) | ||

| Mild | 96 (61.93) | ||

| Moderate-severe | 50 (32.25) | ||

| Missing | 5 (3.2) | ||

| Crohn's disease (n = 103) | |||

| Behavior | |||

| B1 | 93 (90.3) | ||

| B2 | 6 (5.8) | ||

| B3 | 4 (3.9) | ||

| Location | |||

| L1 | 17 (16.7) | ||

| L2 | 30 (39.4) | ||

| L3 | 55 (53.4) | ||

| L4 | 50 (48.5) | ||

| Perianal disease | 34 (33) | ||

| UC/IBD-U (n = 52) | |||

| Location | |||

| E1 | 13 (25) | ||

| E2 | 12 (23.1) | ||

| E3 | 10 (19.2) | ||

| E4 | 17 (32.7) | ||

| Diagnosis | |||

| IBS/functional abdominal pain | 38 (41.8) | ||

| Infection | 6 (6.6) | ||

| Other inflammatory disease | 16 (17.6) | ||

| Polyp | 12 (13.2) | ||

| Other | 19 (20.9) |

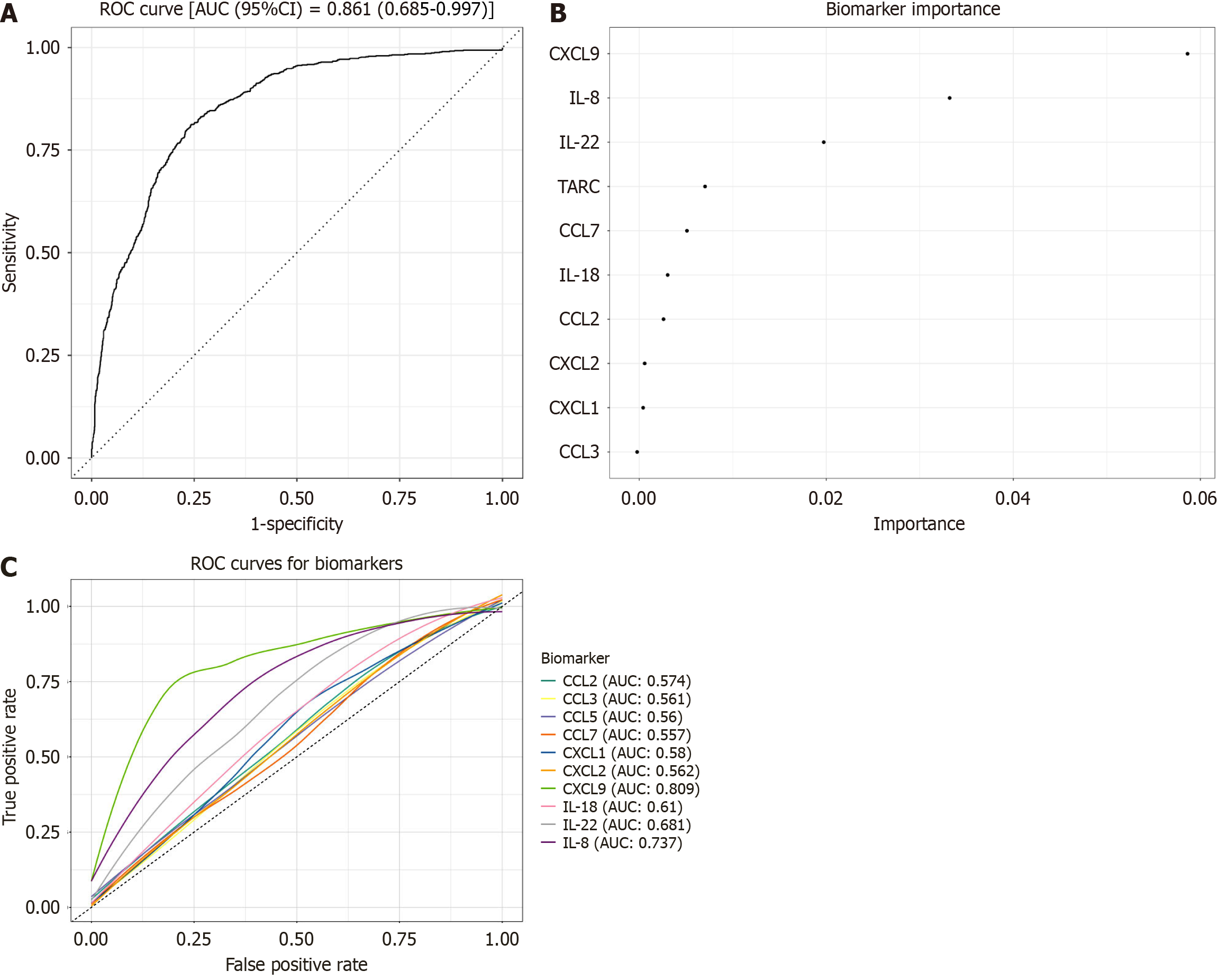

A multivariable model using all 12 biomarkers achieved an AUROC of 0.861 for distinguishing IBD from controls (Figure 1A). Variable importance rankings, from our random forest model identified CXCL9 > IL-22 > IL8 (Figure 1B). We then fitted separate logistic regression models for each biomarker, adjusting for age and sex, and generated ROC curves to assess their individual performance (Figure 1C). CXCL9 showed the greatest diagnostic accuracy (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.81), followed by IL8 (AUC = 0.737) and IL22 (AUC = 0.68).

To evaluate whether the panel could differentiate between IBD subtypes, we compared the concentrations of all 12 analytes between CD (n = 103) and UC (n = 46). Only CXCL9 and IL18 differed significantly (both P = 0.016), with higher levels in CD. Although IL22 and IL8 were elevated overall in IBD, they did not distinguish the subtypes (Table 3). A multivariable model using the full biomarker panel classified CD vs UC poorly (AUROC = 0.60).

| CD (n = 103) | UC (n = 46) | P value | |

| Female, n (%) | 32 (31.1) | 21 (45.7) | 0.125 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.02 | ||

| Western European | 77 (74.8) | 25 (54.3) | |

| South Asian | 9 (8.74) | 11 (23.9) | |

| Other | 17 (16.5) | 10 (21.7) | |

| Age (year) | 12.5 ± 2.71 | 13.6 ± 3.07 | 0.031 |

| Biomarker | |||

| CCL2 | 97.0 ± 36.8 | 111 ± 52.6 | 0.113 |

| CCL5 | 1643 ± 1139 | 1624 ± 665 | 0.897 |

| CCL7 | 259 ± 144 | 245 ± 111 | 0.501 |

| IL-8 | 33.2 ± 186 | 14.4 ± 9.54 | 0.307 |

| TSLP | 268 ± 119 | 290 ± 130 | 0.325 |

| CCL3 | 45.7 ± 15.5 | 43.9 ± 9.96 | 0.399 |

| CXCL1 | 318 ± 253 | 385 ± 353 | 0.248 |

| CXCL2 | 193 ± 155 | 203 ± 261 | 0.814 |

| CXCL9 | 4468 ± 3433 | 3171 ± 2763 | 0.016 |

| IL-18 | 190 ± 218 | 128 ± 91.0 | 0.016 |

| IL-22 | 59.5 ± 199 | 40.2 ± 16.9 | 0.331 |

| TARC | 293 ± 180 | 403 ± 802 | 0.362 |

We also explored whether baseline biomarker levels could predict which children would require biologic therapy during the first year after diagnosis. Among the 123 participants with follow-up data, 75 remained biologicfree (61%). CXCL1 was the only analyte that differed significantly between these groups (mean 415 ± 330 pg/mL vs 297 ± 257 pg/mL; P = 0.039), with lower levels associated with remaining steroidfree and biologicfree (Table 4). CXCL9, IL22, and IL8 were comparable between groups. A predictive model combining all biomarkers achieved an AUROC of roughly 0.60, suggesting the limited ability of baseline cytokine levels alone to forecast early biologic use.

| No biologic treatment (n = 75) | Biologic treatment (n = 48) | P value | |

| Female, n (%) | 33 (44.0) | 12 (25.0) | 0.052 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.56 | ||

| Western European | 50 (66.7) | 34 (70.8) | |

| South Asian | 13 (17.3) | 5 (10.4) | |

| Other | 12 (16.0) | 9 (18.8) | |

| Age (year) | 13.0 ± 3.07 | 12.5 ± 2.39 | 0.353 |

| Biomarker | |||

| CCL2 | 104 ± 37.1 | 105 ± 54.1 | 0.937 |

| CCL5 | 1722 ± 770 | 1798 ± 1479 | 0.742 |

| CCL7 | 283 ± 138 | 269 ± 108 | 0.532 |

| IL-8 | 40.5 ± 217 | 15.1 ± 13.4 | 0.316 |

| TSLP | 308 ± 106 | 286 ± 128 | 0.323 |

| CCL3 | 44.2 ± 11.9 | 46.2 ± 17.3 | 0.498 |

| CXCL1 | 297 ± 257 | 415 ± 330 | 0.039 |

| CXCL2 | 176 ± 204 | 241 ± 201 | 0.083 |

| CXCL9 | 4087 ± 3470 | 4102 ± 2828 | 0.979 |

| IL-18 | 137 ± 123 | 214 ± 280 | 0.08 |

| IL-22 | 64.9 ± 233 | 43.8 ± 16.0 | 0.438 |

| TARC | 379 ± 641 | 288 ± 146 | 0.238 |

A personalized approach is essential for the effective management of PIBD, emphasizing the importance of tailoring treatment strategies to individual patients. Recent studies have highlighted the potential utility of serum biomarkers in predicting both diagnosis and therapeutic outcomes in IBD. Given the critical importance of early intervention and disease control, particularly in CD[1], there is growing interest in identifying biomarkers capable of predicting disease progression. While the top-down therapeutic approach has demonstrated efficacy irrespective of serum biomarker profiles or disease severity, an alternative strategy may be warranted. Specifically, there is a need to identify biomarkers that can stratify patients based on their likelihood of achieving favorable outcomes without progression to biologic the

In our study, CXCL9 and IL-22 were identified as key discriminatory biomarkers for IBD, reflecting their crucial roles in immune response and inflammation. Although IL-22 and IL-8 did not reach statistical significance in univariate analyses when comparing IBD to non-IBD patients, both emerged as important contributors within the multivariable classification model. This distinction underscores the difference between single-analyte performance and model-based feature importance: While IL-22 and IL-8 alone showed only modest discriminatory capacity, their combined contribution with other cytokines, particularly CXCL9, improved the overall performance of the diagnostic panel (AUROC = 0.861). These findings suggest that IL-22 and IL-8 may function synergistically within broader biomarker networks rather than serving as robust stand-alone markers.

CXCL9, known for its involvement in T-cell trafficking[18], and IL-22, associated with mucosal immunity and intestinal epithelial barrier integrity[19-21], showed robust diagnostic performance, suggesting a high degree of reliability. IL-22, was already found to be a key biomarker in treatment response in longitudinal studies[22], but was disappointing as a therapeutic target in a Phase 2 study[23]. CXCL9 has recently been identified as a potential predictor of IBD in a study comparing CXCL9 levels in active patients with IBD to non-IBD controls and assessing their association with disease severity[24]. These findings, combined with the results of our study, underscore the need for further investigation into the role of CXCL9 as a biomarker in IBD.

Beyond diagnosis, CXCL9 and IL-18 were found to be significant predictors of CD, with P values of 0.016 for both. This differentiation holds clinical importance given the distinct management strategies required for CD and UC. This observation is consistent with the T helper 1 (Th1)-skewed inflammatory profile of CD, in which IL-18 promotes IFN-γ production and CXCL9 recruits CXCR3+ T cells, amplifying mucosal Th1 responses[25]. A relatively old pediatric study similarly reported elevated systemic IL-18 in children with CD but not in those with UC, supporting its potential as a CD-specific biomarker[26]. CXCL9, produced predominantly by activated macrophages in response to IFN-γ, has also emerged as one of the most upregulated chemokines in the serum of patients with CD, reinforcing its discriminatory role. Indeed, in one large multiplex study, CXCL9 and IL-18 showed among the strongest associations with CD status, under

The study also explored biomarkers predictive of disease progression, identifying low CXCL1 as a potential marker for defense from progression to biologic treatment within 1 year of diagnosis (P = 0.039). High CXCL1 reflects an intense innate inflammatory response, and neutrophil chemoattraction and activation, which often correlates with severe, refractory disease. Notably, a large serologic study identified CXCL1 as a top discriminator of CD vs healthy controls[27], and general IBD research has shown that CXCL1 is elevated during active flares and in patients with extensive inflammation. Moreover, Fang et al[24] observed that active IBD (both UC and CD) is marked by significantly increased M1 macrophages expressing CXCL9/CXCL10 and higher chemokine levels, which decline in remission. This underscores that chemokine elevation tracks with inflammatory burden. Clinically, pediatric patients who ultimately require biologics often present with more systemic inflammation at diagnosis (e.g., high CRP, hypoalbuminemia)[28]. CXCL1 may be a surrogate for this “high-inflammatory” state. Thus, elevated CXCL1 early in disease could flag a robust innate immune activation and mucosal neutrophil infiltrate, portending a more aggressive course. Despite this, the overall prediction model for subclass differentiation and treatment progression exhibited limited accuracy. This highlights the complexity of IBD progression and suggests a need for integrating additional biomarkers and clinical factors to enhance predictive capabilities.

This study represents one of the largest pediatric cohorts evaluated for serum cytokine biomarkers in IBD to date and addresses an important gap in non-invasive diagnostics. However, despite its promising findings, it has several limi

The results of this study offer several practical applications and research avenues such as early identification, early differentiation, monitoring and treatment prediction. Our findings suggest that these biomarkers may serve as a useful triage tool in clinical practice, helping to prioritize which patients should undergo invasive procedures. Children without ele

| 1. | Levine A, Koletzko S, Turner D, Escher JC, Cucchiara S, de Ridder L, Kolho KL, Veres G, Russell RK, Paerregaard A, Buderus S, Greer ML, Dias JA, Veereman-Wauters G, Lionetti P, Sladek M, Martin de Carpi J, Staiano A, Ruemmele FM, Wilson DC; European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. ESPGHAN revised porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:795-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 822] [Cited by in RCA: 1054] [Article Influence: 87.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schneck E, Knittel F, Markmann M, Balzer F, Rubarth K, Zajonz T, Schreiner AL, Hecker A, Naehrlich L, Koch C, Laffolie J, Sander M. Assessment of risk factors for adverse events in analgosedation for pediatric endoscopy: A 10-year retrospective analysis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2024;79:382-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, D'Amico F, Dhaliwal J, Griffiths AM, Bettenworth D, Sandborn WJ, Sands BE, Reinisch W, Schölmerich J, Bemelman W, Danese S, Mary JY, Rubin D, Colombel JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Dotan I, Abreu MT, Dignass A; International Organization for the Study of IBD. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1570-1583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 473] [Cited by in RCA: 1947] [Article Influence: 389.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Hu T, Wang W, Song F, Zhang W, Yang J. Fecal Calprotectin in Predicting Relapse of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Pediatr Ann. 2023;52:e357-e362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vernon-Roberts A, Humphrey O, Day AS. Exploring the Diagnostic Spectrum of Children with Raised Faecal Calprotectin Levels. Children (Basel). 2024;11:420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Holtman GA, Lisman-van Leeuwen Y, Day AS, Fagerberg UL, Henderson P, Leach ST, Perminow G, Mack D, van Rheenen PF, van de Vijver E, Wilson DC, Reitsma JB, Berger MY. Use of Laboratory Markers in Addition to Symptoms for Diagnosis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children: A Meta-analysis of Individual Patient Data. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:984-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kessel C, Lavric M, Weinhage T, Brueckner M, de Roock S, Däbritz J, Weber J, Vastert SJ, Foell D. Serum biomarkers confirming stable remission in inflammatory bowel disease. Sci Rep. 2021;11:6690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Leppkes M, Neurath MF. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel diseases - Update 2020. Pharmacol Res. 2020;158:104835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Aebisher D, Bartusik-Aebisher D, Przygórzewska A, Oleś P, Woźnicki P, Kawczyk-Krupka A. Key Interleukins in Inflammatory Bowel Disease-A Review of Recent Studies. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;26:121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vebr M, Pomahačová R, Sýkora J, Schwarz J. A Narrative Review of Cytokine Networks: Pathophysiological and Therapeutic Implications for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Pathogenesis. Biomedicines. 2023;11:3229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Singh UP, Singh NP, Murphy EA, Price RL, Fayad R, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS. Chemokine and cytokine levels in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Cytokine. 2016;77:44-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bourgonje AR, von Martels JZH, Gabriëls RY, Blokzijl T, Buist-Homan M, Heegsma J, Jansen BH, van Dullemen HM, Festen EAM, Ter Steege RWF, Visschedijk MC, Weersma RK, de Vos P, Faber KN, Dijkstra G. A Combined Set of Four Serum Inflammatory Biomarkers Reliably Predicts Endoscopic Disease Activity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 2019;6:251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kaz AM, Venu N. Diagnostic Methods and Biomarkers in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Diagnostics (Basel). 2025;15:1303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ott A, Tutdibi E, Goedicke-Fritz S, Schöpe J, Zemlin M, Nourkami-Tutdibi N. Serum cytokines MCP-1 and GCS-F as potential biomarkers in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0288147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Korolkova OY, Myers JN, Pellom ST, Wang L, M'Koma AE. Characterization of Serum Cytokine Profile in Predominantly Colonic Inflammatory Bowel Disease to Delineate Ulcerative and Crohn's Colitides. Clin Med Insights Gastroenterol. 2015;8:29-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Torres J, Petralia F, Sato T, Wang P, Telesco SE, Choung RS, Strauss R, Li XJ, Laird RM, Gutierrez RL, Porter CK, Plevy S, Princen F, Murray JA, Riddle MS, Colombel JF. Serum Biomarkers Identify Patients Who Will Develop Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Up to 5 Years Before Diagnosis. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:96-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 34.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tatsuki M, Hatori R, Nakazawa T, Ishige T, Hara T, Kagimoto S, Tomomasa T, Arakawa H, Takizawa T. Serological cytokine signature in paediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease impacts diagnosis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:14638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Eckert EC, Nace RA, Tonne JM, Evgin L, Vile RG, Russell SJ. Generation of a Tumor-Specific Chemokine Gradient Using Oncolytic Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Encoding CXCL9. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2020;16:63-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kuchař M, Sloupenská K, Rašková Kafková L, Groza Y, Škarda J, Kosztyu P, Hlavničková M, Mierzwicka JM, Osička R, Petroková H, Walimbwa SI, Bharadwaj S, Černý J, Raška M, Malý P. Human IL-22 receptor-targeted small protein antagonist suppress murine DSS-induced colitis. Cell Commun Signal. 2024;22:469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Keir M, Yi Y, Lu T, Ghilardi N. The role of IL-22 in intestinal health and disease. J Exp Med. 2020;217:e20192195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 57.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Patnaude L, Mayo M, Mario R, Wu X, Knight H, Creamer K, Wilson S, Pivorunas V, Karman J, Phillips L, Dunstan R, Kamath RV, McRae B, Terrillon S. Mechanisms and regulation of IL-22-mediated intestinal epithelial homeostasis and repair. Life Sci. 2021;271:119195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bertin L, Barberio B, Gubbiotti A, Bertani L, Costa F, Ceccarelli L, Visaggi P, Bodini G, Pasta A, Sablich R, Urbano MT, Ferronato A, Buda A, De Bona M, Del Corso G, Massano A, Angriman I, Scarpa M, Zingone F, Savarino EV. Association between Ustekinumab Trough Levels, Serum IL-22, and Oncostatin M Levels and Clinical and Biochemical Outcomes in Patients with Crohn's Disease. J Clin Med. 2024;13:1539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Danese S, Rothenberg ME, Lim JJ, Ding HT, McBride JM, Chen Y, Dash A, Mar JS, Keir M, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Panes J, Colombel JF, Feagan B, Valentine JF, Schreiber S. A Randomized Phase II Study of Efmarodocokin Alfa, an interleukin-22 Agonist, Versus Vedolizumab in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;23:1387-1397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fang Z, Qu S, Ji X, Zheng C, Mo J, Xu J, Zhang J, Shen H. Correlation between PDGF-BB and M1-type macrophage in inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rubinstein A, Kudryavtsev I, Arsentieva N, Korobova ZR, Isakov D, Totolian AA. CXCR3-Expressing T Cells in Infections and Autoimmunity. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2024;29:301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Leach ST, Messina I, Lemberg DA, Novick D, Rubenstein M, Day AS. Local and systemic interleukin-18 and interleukin-18-binding protein in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:68-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Boucher G, Paradis A, Chabot-Roy G, Coderre L, Hillhouse EE, Bitton A, Des Rosiers C, Levings MK, Schumm LP, Lazarev M, Brant SR, Duerr R, McGovern D, Silverberg MS, Cho J, Lesage S, Rioux JD; iGenoMed Consortium; NIDDK IBD Genetics Consortium. Serum Analyte Profiles Associated With Crohn's Disease and Disease Location. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28:9-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Buczyńska A, Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk U. Prognostic Factors of Biologic Therapy in Pediatric IBD. Children (Basel). 2022;9:1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Turner D, Hyams J, Markowitz J, Lerer T, Mack DR, Evans J, Pfefferkorn M, Rosh J, Kay M, Crandall W, Keljo D, Otley AR, Kugathasan S, Carvalho R, Oliva-Hemker M, Langton C, Mamula P, Bousvaros A, LeLeiko N, Griffiths AM; Pediatric IBD Collaborative Research Group. Appraisal of the Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1218-1223. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hyams J, Markowitz J, Otley A, Rosh J, Mack D, Bousvaros A, Kugathasan S, Pfefferkorn M, Tolia V, Evans J, Treem W, Wyllie R, Rothbaum R, del Rosario J, Katz A, Mezoff A, Oliva-Hemker M, Lerer T, Griffiths A; Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease Collaborative Research Group. Evaluation of the Pediatric Crohn Disease Activity Index: A Prospective Multicenter Experience. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:416-421. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/