Published online Feb 16, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i5.117981

Revised: January 6, 2026

Accepted: January 26, 2026

Published online: February 16, 2026

Processing time: 52 Days and 14.4 Hours

Multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) pose a major threat to hospital care, with antimicrobial resistance contributing to an estimated 4.95 million deaths globally in 2019 (including 1.27 million directly attributable deaths). India carries a particularly high burden.

To evaluate clinical outcomes associated with MDRO isolation in a tertiary-care center and identifies actionable signals to strengthen infection prevention and targeted antimicrobial stewardship.

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of culture-confirmed MDRO infections treated as pathogens at All India Institute of Medical Sciences Rishikesh from May 2021 to November 2024 using E-Hospital records. Incomplete datasets were ex

A total of 1598 MDRO infected patients were included (mean age 42.8 years; 58.5% male). Overall mortality was 20.8%. ICU care was required in 439 patients (27.5%), and 29.2% had at least one comorbidity. Among ICU patients, 143 (32.6%) were isolated and 296 (67.4%) were not. Mortality did not differ significantly between isolated (46%) and non-isolated (54%) groups (χ² = 2.4; P = 0.12). However, isolated ICU patients had significantly longer ICU LOS (20.5 ± 18.4 days vs 16.4 ± 14.4 days; U = 244157.5; P < 0.001) and hospital LOS (33.7 ± 22.8 days vs 26.9 ± 21.8 days; U = 238460.5; P < 0.001). Most MDRO cases originated from internal medicine (16.3%), general surgery (14.7%), and trauma surgery (13.8%). Duration of antibiotic therapy varied significantly across departments (F = 5.03; P < 0.001). Quarterly trends demonstrated significant fluctuations in MDRO prevalence, hospital LOS (χ² = 200; P < 0.001), and antibiotic utilization (χ² = 252; P < 0.001).

MDRO infections are associated with substantial mortality and prolonged ICU and hospital stays. Marked interdepartmental variability in antibiotic use highlights the need for strengthened infection-prevention practices and targeted antimicrobial stewardship, including de-escalation, intravenous-to-oral switching, and optimized treatment durations to reduce selection pressure. Limited culture availability during 2022 was a key constraint. The associations observed between isolation status and clinical outcomes further highlight the importance of rein

Core Tip: Multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) pose a significant threat to hospital care, particularly in high-burden settings such as India, contributing substantially to antimicrobial resistance-related morbidity and mortality. This study aimed to evaluate clinical outcomes associated with MDRO isolation in a tertiary-care hospital and to identify actionable gaps to strengthen infection prevention and targeted antimicrobial stewardship. A key finding was that while isolation did not significantly reduce mortality among Intensive care unit (ICU) patients, it was associated with significantly longer ICU and hospital length of stay.

- Citation: Pandy P, Singh H, Omar BJ, Kumari D, Panda PK. Clinical outcomes of multidrug-resistant organism infections in a tertiary care hospital in India. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(5): 117981

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i5/117981.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i5.117981

Multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) pose a significant and growing threat to global public health, especially in healthcare settings. These pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin-resistant Enterococci, extended-spectrum β-lactamase -producing Enterobacteriaceae, and carbapenem-resistant organisms such as Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii, cause infections that are difficult to treat due to resistance to multiple antibiotic classes[1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the important global public health threats facing humanity[2]. The WHO’s Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System report (2024) indicates that over 4.95 million deaths worldwide were linked to drug-resistant infections in 2019 alone, with 1.27 million directly caused by AMR[3]. A large number of these infections occur in hospitals, particularly in intensive care units (ICUs), where patients are subjected to broad-spectrum antibiotics, and extended hospital stays-risk factors contributing to the development and spread of MDROs[4].

In India, burden of MDROs is particularly concerning. Data from the Indian Council of Medical Research AMR sur

Understanding local trends in MDRO prevalence, resistance patterns, and associated clinical outcomes is crucial for developing effective infection control policies and antimicrobial stewardship interventions. This study aims to analyze the burden of MDROs, assess temporal trends, and examine the clinical outcomes of affected patients in a tertiary care institute.

A cross-sectional study was conducted using patient data from admitted patients at All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Rishikesh. Data was extracted from the E-hospital, an online patient portal managed by the Government of India, between May 2021 and November 2024.

All hospital admissions at AIIMS Rishikesh with culture-positive MDRO infections were included. Admissions with incomplete or invalid data were excluded.

Patient charts and discharge summaries were reviewed from the E-hospital website. Initially, all hospital admissions at AIIMS Rishikesh with multidrug-resistant infections between May 2021 and November 2024 were shortlisted. Those MDRO patients were isolated were compared with those non-isolated in the given treatment area. Relevant data was then extracted from patient discharge summaries.

A structured Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology flowchart was designed to illustrate the patient selection process, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and final dataset composition. This flowchart provides a clear visualization of study methodology and patient categorization.

All admitted MDRO infected cases which the clinician treats as pathogen. Patient medical records available from 2021 to 2024.

Jamovi software was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics summarized demographic data, while χ2 tests assessed associations between MDRO prevalence and factors such as range of hospital stay, outcomes, presence of comorbidities, antibiotic usage and hospital department. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To ensure the confidentiality of study participants, no personal identifiers were disclosed. Informed consent was waived by the ethics committee, considering a hospital record-based study. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the institutional ethics committee of AIIMS Rishikesh.

A total of 1598 patients were included in our study. The mean age was 42.8 years while the age ranged from less than a day to 95 years. 58.5% of the participants were male and the rest were female. 29.2% of the admitted cases had at least 1 comorbidity. 439 patients (27.5%) stayed in the ICU during their hospital admission. Most of the participants with a history of stay in the ICU were male (61.0%). 29.2% of the participants who were MDRO infected had at least 1 co

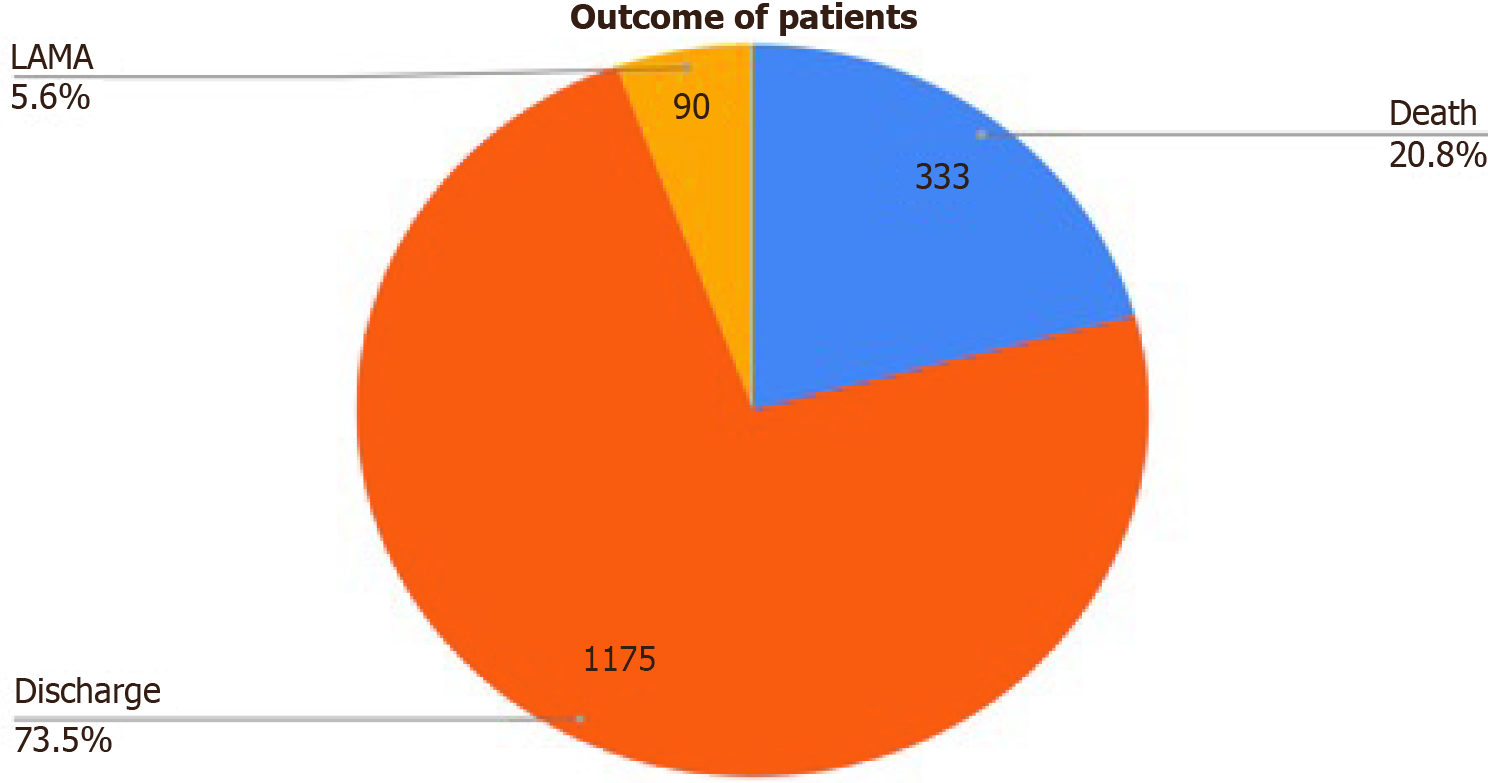

Mortality: 20.8% of the participants died during the course of hospital admission while 73.5% were discharged in hemodynamically stable condition. Figure 1 shows details of the outcome of cases. Death has occurred in 66 patients (46%) in isolated group and 160 patients (54%) in non-isolated group with no statistical significance (χ2 = 2.4; P = 0.12).

Length of stay: Out of 143 requiring isolation, their mean ICU stay was 20.5 ± 18.4 days, and their mean total hospital stay was 33.7 ± 22.8 days. The remaining 296 non-isolated patients had a mean ICU stay of 16.4 ± 14.4 days and a mean total hospital stay of 26.9 ± 21.8 days. And there is significance association between isolation and ICU stay (U = 244157.5, P < 0.001) and hospital stay (U = 238460.5, P < 0.001). Range of the hospital stay has been shown in Table 1. Most of the patients were admitted to the hospital for 11-25 days. At least 1 antibiotic was used in 460 patients (28.8%) with MDRO infection.

| Duration of hospital stay (days) | Non-ICU | ICU-isolated | ICU-non-isolated | Total |

| ≤ 7 | 254 | 10 | 42 | 306 |

| 8-14 | 293 | 21 | 52 | 366 |

| 15-21 | 205 | 25 | 52 | 282 |

| 22-28 | 128 | 13 | 36 | 177 |

| 29-42 | 143 | 32 | 67 | 242 |

| 43-60 | 102 | 21 | 29 | 152 |

| > 60 | 34 | 21 | 18 | 73 |

| Total | 1159 | 143 | 296 | 1598 |

There was a significant difference between the range of hospital stay and presence of comorbidities in the participants. This is shown in Table 2. There was also a significant difference between the presence of ICU stay and the outcome of the individual with a χ2 value of 368 (P < 0.001). There was also a strong association between invasive ventilation and outcome with P < 0.001.

| Range of hospital stay (days) | Presence of comorbidities | |

| Yes | No | |

| ≤ 3 | 30 | 46 |

| 4-10 | 142 | 251 |

| 11-25 | 166 | 438 |

| 26-50 | 94 | 289 |

| 51-100 | 33 | 102 |

| > 100 | 1 | 6 |

| Total | 466 | 1132 |

Department-wise outcome of MDRO-infected patients: Most of the MDRO cases were from the departments of internal medicine (16.3%), general surgery (14.7%) and trauma surgery (13.8%). There was a significant difference in the department of admission of patients and their outcomes (Table 3). There was also a significant association between the presence of ICU stay and outcome of the patient with P < 0.001. There was a significant association (P = 0.002) between the outcome and type of MDRO infection (hospital- or community-acquired).

| Department | Outcome | |||

| Discharge | Death | LAMA | Total | |

| Neurology | 44 | 11 | 4 | 59 |

| Nephrology | 64 | 5 | 1 | 70 |

| Neurosurgery | 126 | 42 | 6 | 174 |

| General surgery | 187 | 42 | 6 | 235 |

| Trauma surgery | 175 | 36 | 10 | 221 |

| Pulmonary medicine | 65 | 27 | 7 | 99 |

| Gastroenterology | 12 | 5 | 0 | 17 |

| Emergency medicine | 40 | 26 | 18 | 84 |

| Otorhinolaryngeology | 16 | 18 | 1 | 35 |

| Internal medicine | 186 | 55 | 19 | 260 |

| Medical hematology-oncology | 73 | 11 | 2 | 86 |

| Surgical oncology | 16 | 2 | 1 | 19 |

| Pediatrics | 12 | 3 | 2 | 17 |

| Radiation oncology | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| Physical medicine & rehabilitation | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Cardiology | 25 | 0 | 1 | 26 |

| Urology | 27 | 2 | 1 | 30 |

| Burns & plastic surgery | 11 | 1 | 0 | 12 |

| Obstetrics & gynaecology | 26 | 3 | 3 | 32 |

| Dermatology | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Endocrinology | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Geriatric medicine | 5 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| Cardiothoracic and vascular surgery | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Orthopaedics | 8 | 4 | 0 | 12 |

| Neonatology | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| Surgical gastroenterology | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| Radiotherapy | 5 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Medicine-intensive care unit | 29 | 30 | 8 | 67 |

| Total | 1175 | 333 | 90 | 1598 |

Antimicrobial exposure and heterogeneity of treatment: The duration of treatment (DOT) with various classes of antibiotics given to the participants during their hospital stay has been mentioned in Table 4. The variance of DOT of antibiotics varies significantly across departments [F (27, 2702) = 5.03, P < 0.001].

| Class of antibiotic | DOT |

| Aminoglycosides | 1413 |

| Anthelmintic | 71 |

| Antifungal: Antimetabolite | 79 |

| Antifungal: Azole | 804 |

| Antifungal: Echinocandin | 299 |

| Antifungal: Polyene | 449 |

| Antimalarial | 16 |

| Antitubercular drugs | 2455 |

| Antiviral: Direct-acting antivirals | 40 |

| Antiviral: HAART | 189 |

| Antiviral: Neuraminidase inhibitors | 114 |

| Antiviral: NS5 polymerase inhibitors | 92 |

| Antiviral: Nucleoside analogue | 285 |

| Beta lactamase inhibitor | 4452 |

| Carbapenems | 4587 |

| Cephalosporins | 3279 |

| Fluoroquinolones | 1640 |

| Folic acid synthesis Inhibitors | 910 |

| Glycopeptides | 2728 |

| Lincosamides | 604 |

| Macrolide | 562 |

| Monobactam | 169 |

| Nitrofurans | 195 |

| Nitroimidazoles | 1393 |

| Other antibiotics (unknown) | 1465 |

| Oxazolidonones | 1243 |

| Penicillins | 3907 |

| Phosphonates | 64 |

| Polymixins | 2322 |

| Rifamycins | 956 |

| Tetracyclines | 1229 |

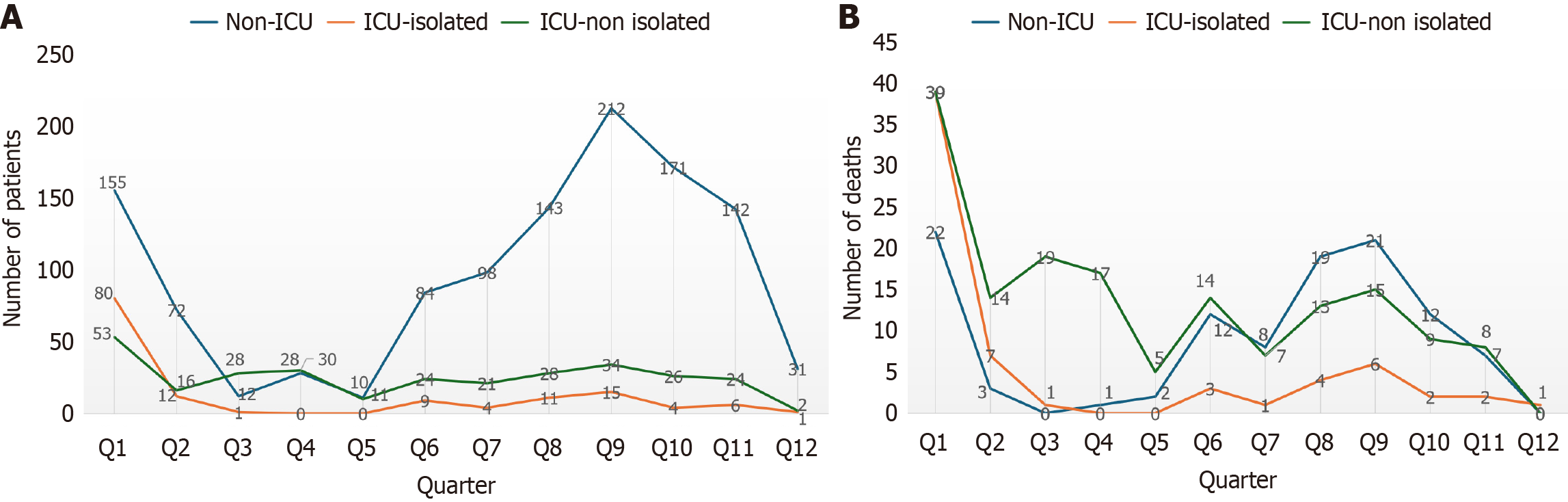

Temporal fluctuations in burden, length of stay, and antibiotic use: The quarter wise prevalence of MDRO cases has been shown in Figure 2. There was a significant difference in mortality between quarters of the year χ² (11, n = 1598) = 98.5, P < 0.001. There was a significant association between the range of hospital stay and quarters of the years with χ² (65, n = 1598) = 200, P < 0.001. There was also a significant association between the usage of antibiotics in various quarters with χ² (13, n = 1598) = 252, P < 0.001.

The demographic and clinical presentation data highlight the risk factors of the study population (n = 1598), like exposure to the ICU environment, significant comorbidity burden, and prolonged hospitalization. The finding that 439 patients (27.5%) stayed in the ICU during their admission is crucial, as the ICU setting is well recognized as a major driver for both MDRO acquisition and poor patient outcomes[7,8]. Patients admitted to the ICU are particularly vulnerable to MDRO infections due to critical illness and the frequent use of invasive devices. Critically ill patients in the ICU are 5 to 10 times more likely to acquire a healthcare-associated infection (HAI) than those in general wards[7-9]. The ICU environment itself is highly influential on MDRO presence. A study focusing on bloodstream infections in critical care units in Indonesia highlighted that critical care factors like endotracheal tube (ETT) use [adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 2.30] and the use of immune suppression medication (adjusted OR = 2.709) were significant factors that increase bacterial resistance in bloodstream infection[9]. In the Malaysian national surveillance study, ICU stay was reported as a risk factor for mortality in patients with Bloodstream Infections (BSIs) caused by MDROs, noting that critical conditions increase the risk of death[10]. In this study, this correlation is strongly supported by the finding of a significant association between the presence of ICU stay and the patient outcome (χ2 = 368, P < 0.001), which aligns with consistent findings in the literature.

The observation that 29.2% of admitted cases had at least 1 comorbidity signifies that a substantial portion of the population possesses underlying conditions that heighten vulnerability to severe MDRO infections. Comorbidities are generally understood to influence the emergence of bacterial resistance, MDRO colonization risk, and patient immune status[9]. In a pediatric ICU (PICU) study in Argentina, 32.5% of included patients had a comorbidity detected. Common underlying conditions noted in international studies that predispose patients to infection include prematurity, chronic pulmonary disease, congenital heart disease, and oncologic/hematologic disease[7]. In the larger context of HAI in adult Spanish hospitals, specific comorbidities like peripheral vascular disease, dementia, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome were found to be more prevalent in patients with MDRO-HAIs. Severity of underlying illness, as captured by scales like the Charlson comorbidity index and McCabe severity scale, is repeatedly found to be a major independent factor associated with increased mortality in MDRO infections[8]. This study further establishes a functional link between patient health status and hospitalization duration, finding a significant difference between the range of hospital stay and the presence of comorbidities (P = 0.001).

A large retrospective study in an Italian teaching hospital found that patients with at least one MDRO isolation had a risk of in-hospital mortality that was 3.4 times higher than those without MDRO (OR: 3.4; 95%CI: 2.8-4.2). The total percentage of deceased patients in the MDRO cohort in that Italian study was 18%, which is comparable to our finding of 20.8% mortality[11]. Similarly, a Spanish retrospective cohort study focused on HAIs found that the risk of hospital mortality was 1.7 times higher (hazard ratio: 1.7; 95%CI: 1.25-2.32) for patients with HAI-MDRO compared to those with susceptible strains (where the overall in-hospital mortality was 24.1% in cases vs 15.4% in controls)[12]. In a Malaysian national surveillance analysis of MDROs (2018-2022), the overall mortality outcome among MDRO-infected patients was 9.6%. The Malaysian data demonstrate that the presence of Gram-negative bacteria and HAIs significantly increases the mortality risk[10]. The high mortality rate observed in our cohort, highlights the significant threat posed by MDRO infections in a tertiary care setting in India. This observed mortality rate is higher than the overall mortality rate of 13.1% reported in a separate retrospective, 10-hospital study in India focusing on patients with culture-confirmed bacterial infections. This difference suggests fatal outcomes with MDRO infection, and need of vigilant evaluation and ste

In this study the finding that most of the patients were admitted to the hospital for 11-25 days (37.8%) confirms that MDRO infection contributes significantly to morbidity, characterized by prolonged hospitalization. While examining the economic burden, an ICU stay in a United States study was associated with a 142% increase in total hospital cost and an almost 106% increase in length of stay (LOS) compared to patients without ICU stays, regardless of the resistance status of the Gram-negative pathogen[8]. MDRO infections are strongly linked to extended hospitalizations and higher costs globally[7,8]. A specific Italian hospital study found that patients with MDRO had a mean LOS of 32.8 days, roughly five times longer than patients without MDRO isolation (mean LOS 7.2 days)[12]. In the United States context, HAIs caused by resistant Gram-Negative pathogens were associated with an additional 23.8% increase in LOS compared to susceptible pathogens[8]. The impact on pediatric intensive care is particularly severe; MDRO infections in Argentine PICUs were associated with a significantly longer ICU stay of 81 days (median) compared to non-MDRO infections (median 25 days)[7]. However, some studies, such as the retrospective Spanish cohort study on HAIs, found that MDRO exposure did not appear to influence LOS in adjusted models, suggesting that variables like patient severity, previous hospitalization, and ICU stay are the main determinants of over-staying[8]. Over all, the elevated ICU admission rate and the significant comorbidity burden in this cohort provide powerful explanatory factors for the high MDRO prevalence and the resulting prolonged hospital stays, confirming the challenge of managing these infections in a high-acuity, resource-intensive setting. The strong statistical association found between ICU stay and clinical outcome reinforces the urgent need for targeted infection control and antimicrobial stewardship efforts within critical care units[10,12].

In this study we find that most MDRO cases originated from internal medicine (16.3%), general surgery (14.7%), and trauma surgery (13.8%) reflect the concentration of critically ill patients in these major clinical services. These de

MDRO infections are inherently linked to antibiotic exposure, as the irrational use of antibiotics is a primary factor in the emergence of resistance. The mechanism of action, indication, dosage, frequency, and duration of therapy may all influence the development of bacterial resistance. Most critically, the indication for antibiotic use is a major factor. Retrospective analysis in critical care units in Indonesia found that non-surgical prophylactic antibiotic use was sig

The extensive DOT documented for various antibiotics in Table 4 describes the intensity and complexity of managing these infections. The high DOTs reported for broad-spectrum and last-resort antibiotics indicate the necessary steps taken to combat highly resistant organisms in this population: Antibiotics such as pipercillin-tazobactum (6314 DOT), meropenem (4268 DOT), and colistin (2322 DOT) appear prominently among the most utilized therapeutic options. The necessity of using agents like colistin, linezolid (1243 DOT), tigecycline (475 DOT), and vancomycin (1502 DOT) aligns with global trends where resistance forces clinicians to rely on drugs classified as “Reserve” by the WHO AWaRe classification. In a pediatric ICU study in Argentina, patients with MDRO infections received antibiotics from the Reserve group in 28.6% of cases, compared to only 5.5% of non-MDRO cases[7]. High antibiotic use also contributes to higher hospital costs; studies focused on Gram-Negative HAIs found that HAIs caused by resistant pathogens were associated with a 29.3% higher total hospital cost and a 23.8% longer LOS compared to susceptible infections[8]. The finding that the variance of DOT varies significantly across departments [F (27, 2702) = 5.03, P < 0.001] is expected but warrants investigation into stewardship practices.

The findings showing significant associations between the quarters of the year and prevalence of MDRO cases (Figure 2), range of hospital stay (χ2 = 200, P < 0.001), and antibiotic usage (χ2 = 252, P < 0.001) highlight a strong temporal element influencing the MDRO burden. These temporal trends suggest possible seasonal or climate-driven changes in infection rates and hospital practices, which is a globally recognized phenomenon. The sources indicate that Gram-negative MDROs, which often dominate infection profiles in India, typically demonstrate seasonality, with incidence rates increasing in warmer months or during summer. For instance, the incidence of Gram-negative HABSIs increases by 13.1% for every 5 °C increase in temperature. Conversely, key Gram-positive pathogens, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae, often see their highest resistance rates peaking during the winter season, though Gram-positive HAIs generally show less pronounced seasonality than Gram-negative ones[14,15]. But in our study the finding not correlating with these trends may be due to very less data during coronavirus disease pandemic and demographic var

MDRO infections present a formidable challenge in Indian tertiary care, resulting in a substantial 20.8% mortality rate. This study highlights a critical paradox: While ICU isolation did not significantly reduce mortality (P = 0.12), it was strongly associated with significantly prolonged hospital and ICU stays (P < 0.001). High-risk departments, specifically internal medicine (16.3%) and general surgery (14.7%), bear the greatest burden and demonstrate marked variability in antibiotic utilization. These findings update the urgent necessity for an integrated approach to combat AMR. Beyond standard infection prevention, healthcare facilities must implement targeted antimicrobial stewardship, prioritizing anti

While the study is limited by its cross-sectional design, which weakens the temporal relationship between outcomes, and by a lack of data in 2022 due to limited culture availability, its importance cannot be overstated. This research is vital because it identifies actionable signals essential for strengthening infection-control policies in high-burden regions. By providing evidence-based insights into how high-acuity services and isolation protocols impact patient outcomes, this study offers a crucial roadmap for clinicians to manage resistance and significantly improve the clinical outcome for the most vulnerable patient populations.

| 1. | CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2019. [April 11, 2025]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/data-research/threats/index.html#cdc_research_or_data_summary_suggested_citation-suggested-citation. |

| 2. | World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance. [November 21, 2023]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance. |

| 3. | Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399:629-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8908] [Cited by in RCA: 8939] [Article Influence: 2234.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Vincent JL, Rello J, Marshall J, Silva E, Anzueto A, Martin CD, Moreno R, Lipman J, Gomersall C, Sakr Y, Reinhart K; EPIC II Group of Investigators. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA. 2009;302:2323-2329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2205] [Cited by in RCA: 2418] [Article Influence: 142.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | ICMR AMR Surveillance Report 2022. Indian Council of Medical Research. Available from: https://main.icmr.nic.in. |

| 6. | Zhen X, Lundborg CS, Sun X, Hu X, Dong H. Economic burden of antibiotic resistance in ESKAPE organisms: a systematic review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8:137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cornistein W, Balasini C, Nuccetelli Y, Rodriguez VM, Cudmani N, Roca MV, Sadino G, Brizuela M, Fernández A, González S, Águila D, Macchi A, Staneloni MI, Estenssoro E. Prevalence and Associated Mortality of Infections by Multidrug-Resistant Organisms in Pediatric Intensive Care Units in Argentina (PREV-AR-P). Antibiotics (Basel). 2025;14:493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Mauldin PD, Salgado CD, Hansen IS, Durup DT, Bosso JA. Attributable hospital cost and length of stay associated with health care-associated infections caused by antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:109-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ong DT, Mertaniasih NM, Santoso KH, Atika, Koendhori EB, Endraswari PD. Association between the Antibiotic Factors and the Development of Bacterial Resistance in Bloodstream Infections in the Critical Care Unit. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2025;19:1225-1238. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Wp SE, Norhidayah M, Ar MNA. Factors associated with multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) mortality: an analysis from the national surveillance of multidrug-resistant organism, 2018-2022. BMC Infect Dis. 2025;25:60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Moro M, Vigezzi GP, Callari E, Biancardi A, Nizzero P, Cichero P, Signorelli C, Odone A. Multidrug-resistant organism infections and mortality: estimates from a large Italian hospital. Eur J Public Health. 2020;30:ckaa165.315. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Barrasa-Villar JI, Aibar-Remón C, Prieto-Andrés P, Mareca-Doñate R, Moliner-Lahoz J. Impact on Morbidity, Mortality, and Length of Stay of Hospital-Acquired Infections by Resistant Microorganisms. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:644-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gandra S, Tseng KK, Arora A, Bhowmik B, Robinson ML, Panigrahi B, Laxminarayan R, Klein EY. The Mortality Burden of Multidrug-resistant Pathogens in India: A Retrospective, Observational Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:563-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Blot K, Hammami N, Blot S, Vogelaers D, Lambert ML. Seasonal variation of hospital-acquired bloodstream infections: A national cohort study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2022;43:205-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Asghar MU, Zaidi AH, Tariq M, Ain NU. Seasonal and hospital settings variations in antimicrobial resistance among clinical isolates from cardiac patients: insights from a 7-Year study. BMC Infect Dis. 2025;25:936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/