Published online Jan 16, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i2.116519

Revised: December 4, 2025

Accepted: December 22, 2025

Published online: January 16, 2026

Processing time: 64 Days and 5.7 Hours

Intraosseous lipomas are rare developmental anomalies that present with visual impairment. Due to their infrequency, they often pose diagnostic challenges, par

We present the case of a 41-year-old male with a history of dyslipidemia who developed sudden onset headaches and decreased vision in his left eye. MRI revealed a T1-hyperintense fat-containing lesion within the left anterior clinoid process of the sphenoid bone at the optic canal, causing extrinsic compression of the left optic nerve, initially interpreted as a lipoma. Intraoperatively, the pre

This case highlights the importance of considering intraosseous lipoma of the sphenoid bone as a rare cause of optic nerve compression and emphasizes the pivotal, but not definitive, role of MRI, which must be complemented by surgical and histopathological correlation to prevent irreversible visual loss.

Core Tip: This case report describes a rare intraosseous lipoma of the sphenoid bone causing compressive optic neuropathy and reversible vision loss in a middle-aged patient. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suggested a lipomatous lesion, but definitive diagnosis required intraoperative findings and histopathological confirmation of an adipose tumor of bone. Successful optic nerve decompression led to significant visual recovery. This case underscores the need to consider in

- Citation: Tlaiss Y, Abou Zeki L, Farhat H, Warrak J, Yazbeck M, Al-Awar O. Intraosseous lipoma of the sphenoid bone causing optic nerve compression: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(2): 116519

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i2/116519.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i2.116519

Intraosseous lipomas are rare benign tumors that arise within the medullary cavity of bone and are composed of mature adipocytes. They account for less than 0.1% of all primary bone tumors and are most frequently identified incidentally on imaging studies of the long bones, particularly the proximal femur, tibia, and calcaneus. When located in the skull base, intraosseous lipomas may remain asymptomatic or present with nonspecific symptoms. However, their proximity to critical neurovascular structures can lead to significant clinical manifestations. Compression of the optic nerve by such lesions is exceptionally uncommon, with only a few cases reported in the literature[1,2].

Compression of the optic nerve can result in significant visual morbidity and is typically associated with more common pathologies such as optic nerve gliomas, meningiomas, or inflammatory optic neuropathies[3]. Fat-containing lesions within the orbit or optic canal are uncommon and may lead to diagnostic uncertainty, particularly when their location within the bone obscures the typical characteristics seen in more superficial soft tissue lipomas. In this context, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) plays a pivotal role. Its superior soft tissue contrast allows for the precise characterization of lesion content, extent, and its spatial relationship with critical structures, thereby guiding both diagnosis and surgical planning[4].

We present the case of a 41-year-old male with acute unilateral visual loss due to an intraosseous lipoma compressing the optic nerve at the optic canal. This case is notable for the rare location of the lipoma within the sphenoid bone, the diagnostic challenge it posed due to its imaging appearance, and the successful outcome following surgical de

Acute unilateral visual loss in the left eye, associated with headache.

A 41-year-old male presented with a short history of progressive blurring of vision in his left eye. Over several days, he noticed difficulty with reading and with detecting objects in the left peripheral field, accompanied by intermittent headaches. He denied eye pain, diplopia, photopsia’s, or systemic constitutional symptoms such as fever or weight loss.

The patient had a history of dyslipidemia, controlled with medical therapy. He also had a remote history of significant ocular trauma to the right eye, resulting in traumatic optic neuropathy and no light perception vision in that eye. There was no history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, malignancy, or prior intracranial surgery.

He was a non-smoker and denied alcohol or illicit drug use. Family history was negative for hereditary optic neur

General and systemic physical examinations were unremarkable. Neurological examination showed no focal motor or sensory deficits. On ophthalmologic examination, best corrected visual acuity was no light perception in the right eye (Oculus Dexter) and 20/80 in the left eye (Oculus Sinister). The right pupil was non-reactive, consistent with long

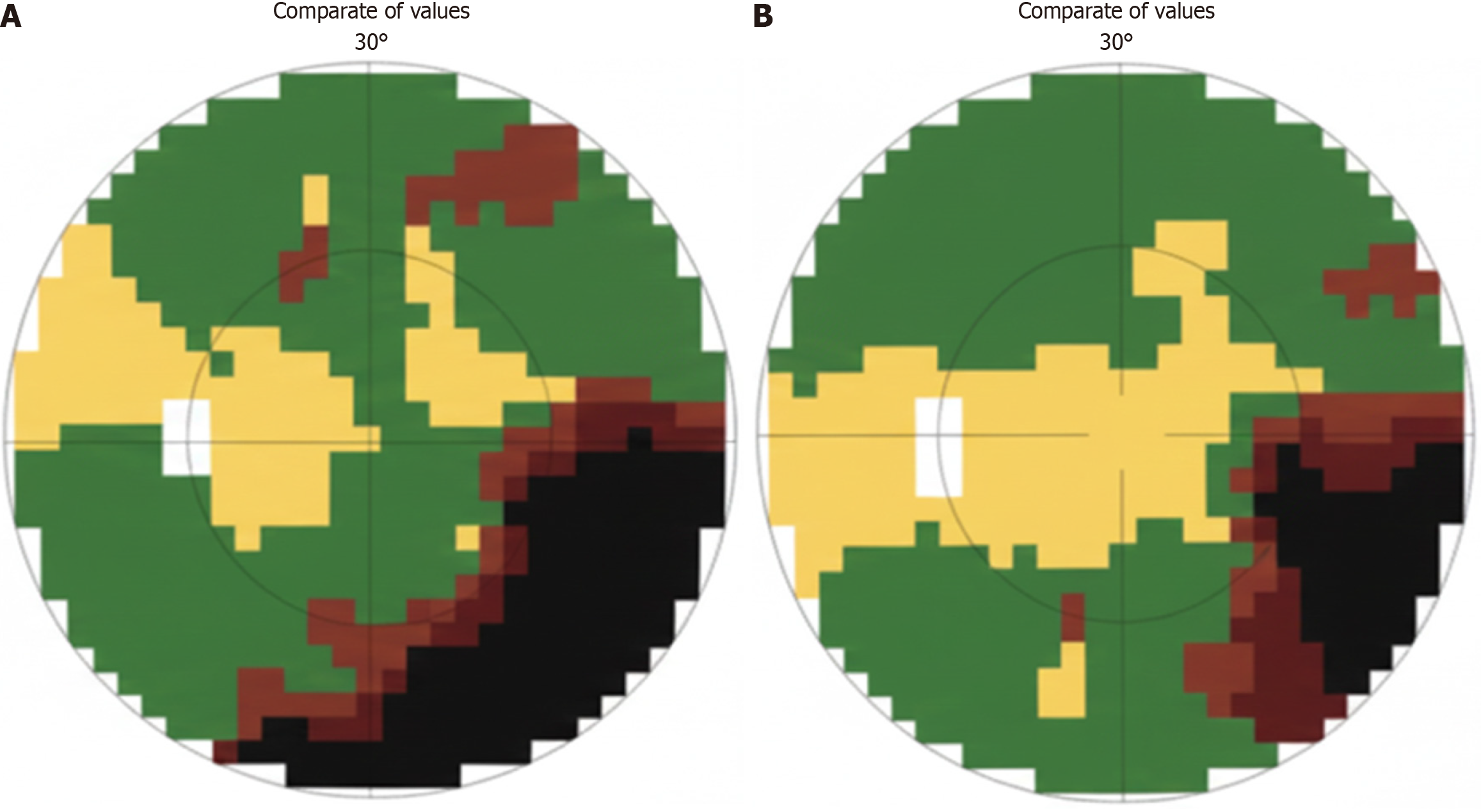

Slit-lamp examination of the left eye revealed a quiet anterior segment without signs of inflammation. Funduscopic examination of the left eye showed marked optic disc swelling consistent with papilledema, whereas the right optic disc demonstrated chronic post-traumatic changes. Visual field testing of the left eye using octopus perimetry demonstrated a significant inferotemporal defect preoperatively, with substantial improvement after treatment, consistent with com

Routine laboratory investigations, including complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and inflammatory markers, were within normal limits and did not suggest an infectious, inflammatory, or metabolic cause for the visual loss.

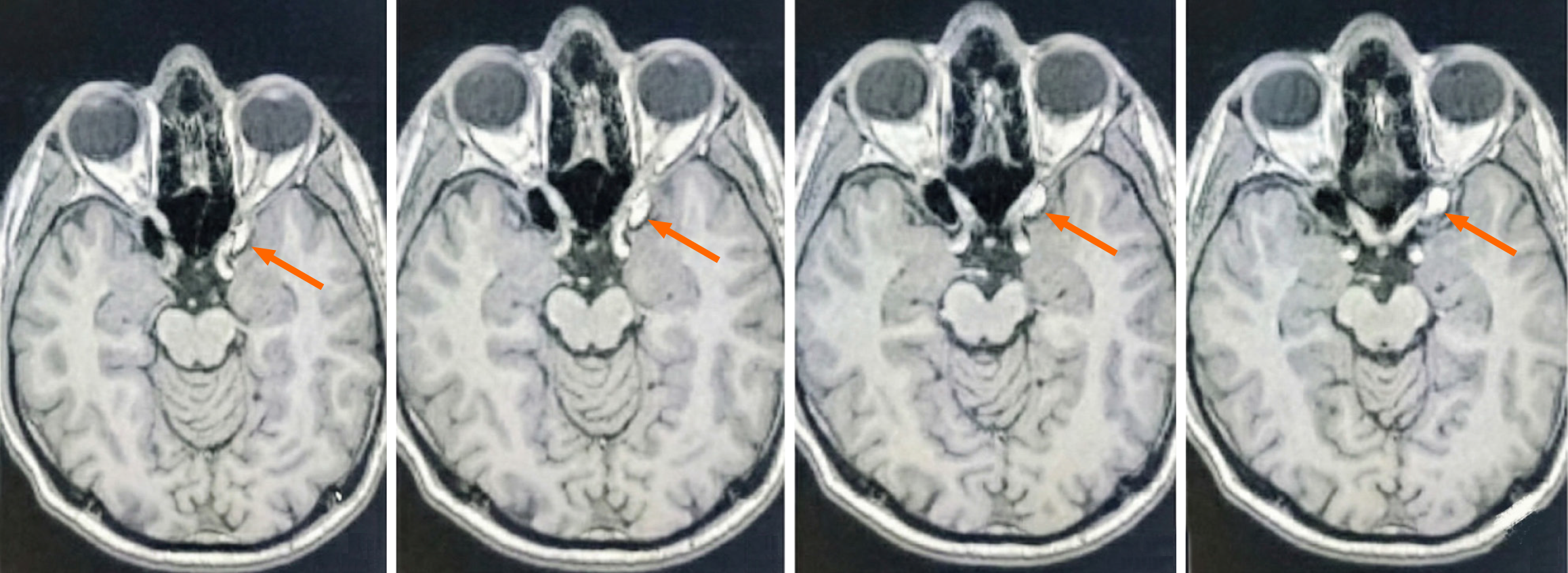

Urgent MRI of the brain and orbits with contrast revealed a T1-hyperintense, fat-containing lesion within the left anterior clinoid process of the sphenoid bone at the level of the optic canal, causing significant extrinsic compression of the left optic nerve (Figure 2). The lesion demonstrated signal characteristics compatible with adipose tissue on fat-sensitive sequences. No additional intracranial mass, acute ischemia, or hydrocephalus was identified.

These findings were most consistent with an intraosseous lipoma of the sphenoid/anterior clinoid process compressing the optic nerve, while acknowledging that other fat-containing lesions (e.g., dermoid cysts or lipomatous variants) can have overlapping imaging features.

The case was discussed at a multidisciplinary meeting involving neurosurgery, ophthalmology, and neuroradiology. Based on the acute unilateral visual decline, the presence of papilledema, visual field defect pattern, and MRI evidence of a fat-containing intraosseous lesion at the optic canal, the team concluded that the patient had a compressive optic neuropathy of the left eye secondary to an intraosseous lipoma of the sphenoid/anterior clinoid process.

Given the severity and rapid progression of visual loss, urgent surgical decompression via anterior clinoidectomy with unroofing of the optic canal was recommended to prevent irreversible optic nerve damage.

Intraosseous lipoma of the left sphenoid bone/anterior clinoid process causing compressive optic neuropathy of the left optic nerve with secondary papilledema.

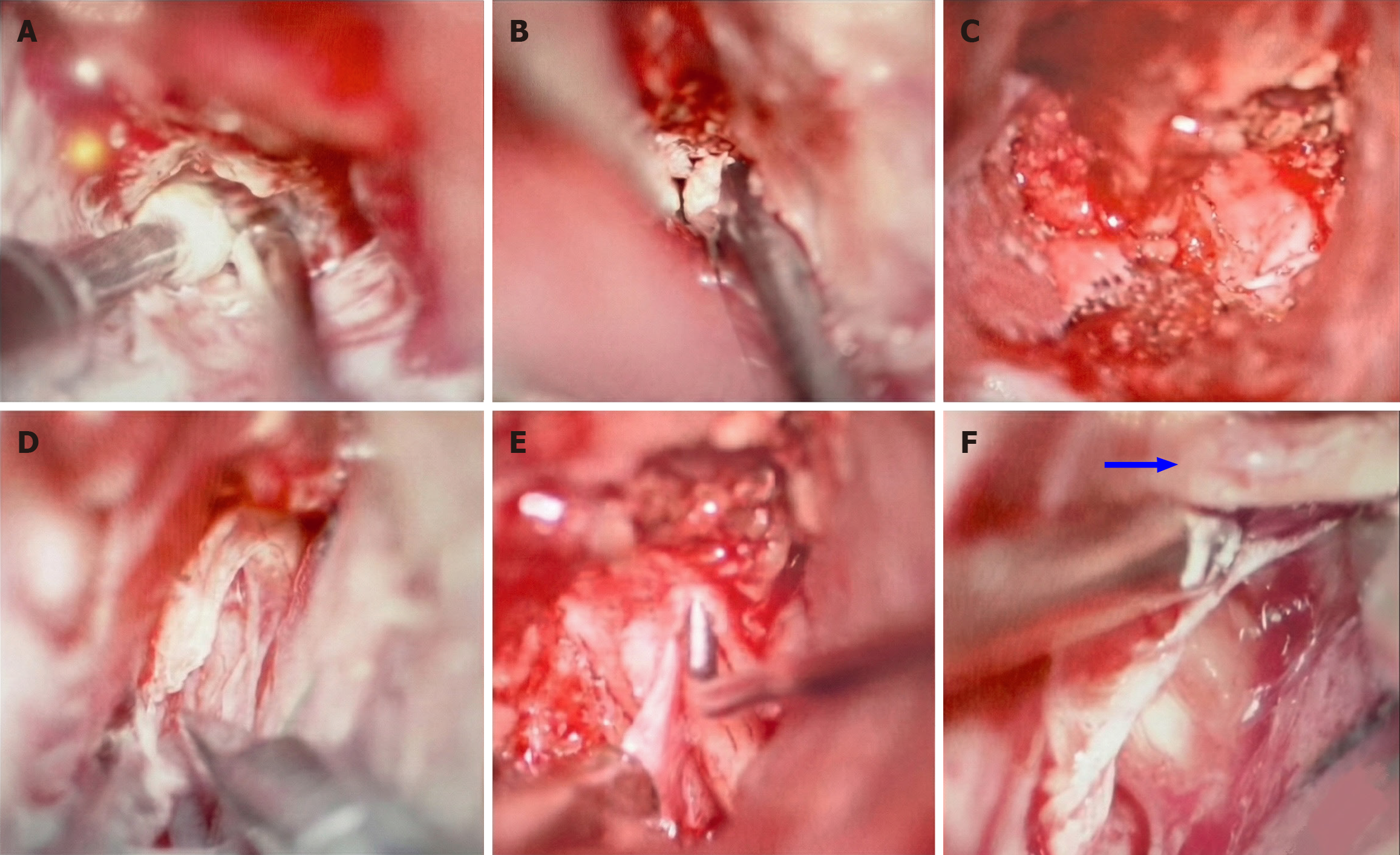

The patient underwent a left pterional craniotomy under general anesthesia. A combined extradural and intradural anterior clinoidectomy was performed with unroofing of the optic canal. The anterior clinoid process was carefully drilled and removed, exposing the optic canal, which was opened medially and posteriorly. Intraosseous fatty tissue consistent with lipoma was identified within the anterior clinoid/sphenoid bone and meticulously debulked, and the thickened, fatty dura overlying the optic nerve was opened to achieve full decompression.

The hybrid extra-/intradural technique allowed safe drilling of the anterior clinoid and complete decompression of the optic nerve while preserving adjacent neurovascular structures (Figure 3). Standard postoperative care was provided in the neurosurgical ward with close neuro-ophthalmologic monitoring.

Postoperatively, the patient showed rapid visual improvement in the left eye. Best corrected visual acuity improved from 20/80 to 20/20 on follow-up. Papilledema resolved, and repeat Octopus perimetry demonstrated marked improvement and near-complete recovery of the inferotemporal field defect (Figure 1, postoperative field).

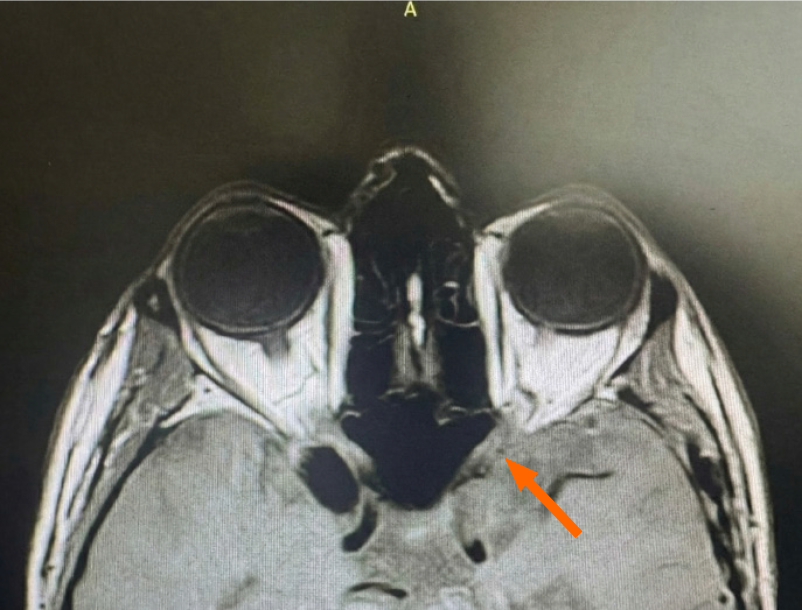

Follow-up axial T1-weighted MRI confirmed successful decompression of the left optic nerve with complete removal of the fat-containing lesion from the optic canal and no residual intraosseous lipoma (Figure 4). The patient remained neurologically stable and visually asymptomatic at subsequent outpatient visits, with no radiological evidence of re

Intraosseous lipomas are rare benign tumors that arise within the medullary cavity of bone and are composed predominantly of mature adipose tissue. They represent approximately 0.1% of all primary bone tumors, with fewer than 300 cases documented in the literature. Involvement of the skull base with secondary optic nerve compression, as in our patient, is exceptionally rare. Although most frequently located in the metaphyseal regions of long bones such as the femur, tibia, and calcaneus, intraosseous lipomas have also been reported in the craniofacial skeleton, including the sphenoid and orbital bones. When situated in these less common sites, particularly near the optic nerve or other critical neurovascular structures, they may present with clinically significant symptoms including headache, visual disturbance, or cranial nerve deficits[5].

Histologically, intraosseous lipomas consist of mature fat cells and can exhibit a spectrum of degenerative changes such as fat necrosis, calcification, cystic transformation, and resorption of trabecular bone. These features have been classified by Milgram into three stages: Stage I lesions contain viable fat without necrosis, stage II lesions exhibit fat necrosis and focal calcification, and stage III lesions show extensive necrosis with cyst formation. This classification provides a framework for understanding the potential evolution and radiologic appearance of intraosseous lipomas[6,7].

MRI and computed tomography (CT) are essential tools for the diagnosis of intraosseous lipomas. On MRI, these lesions typically appear hyperintense on T1-weighted sequences due to their fat content and demonstrate signal loss on fat-suppressed images[8]. CT findings often reveal a well-defined lytic lesion with internal fat density and may show sclerotic margins or central calcification, features that can aid in diagnosis. However, in unusual locations such as the orbit or skull base, the radiologic appearance of intraosseous lipomas can mimic more common lesions including fibrous dysplasia, meningioma, or metastatic disease, leading to potential diagnostic challenges[4].

In the optic canal and skull base region, fat-containing or T1-hyperintense lesions may mimic other pathologies, including dermoid cysts, cavernous hemangiomas, and vascular lesions with intralesional hemorrhage. Recognizing this overlap is important, as MRI signal characteristics alone are rarely pathognomonic. CT complements MRI by identifying bone remodeling, sclerotic margins, and intralesional calcifications that may suggest specific Milgram stages and help distinguish intraosseous lipomas from other osseous or extraosseous masses.

In the present case, the lesion was initially suspected to be a lipoma based on MRI characteristics. However, intraoperative exploration and subsequent histopathological analysis revealed an intraosseous lipoma originating within bone, compressing the optic nerve. This finding underscores the importance of correlating radiologic findings with surgical and pathological data, particularly when managing lesions in anatomically complex or diagnostically ambiguous regions. Our experience underscores both the strengths and limitations of MRI in this context: Although it correctly suggested a fat-containing lesion responsible for optic nerve compression, it did not definitively establish the intraosseous origin or exclude other lipomatous and non-lipomatous mimics. This limitation highlights the necessity of correlating radiologic impressions with intraoperative findings and histopathology when managing atypical skull base lesions.

Management of intraosseous lipomas is generally conservative in asymptomatic patients. However, when these tumors cause functional impairment, as in cases of optic nerve compression, surgical intervention becomes necessary[9]. Decompression of the optic nerve may lead to significant visual improvement or stabilization of symptoms. Complete resection is not typically required unless there is suspicion of malignancy or the lesion demonstrates atypical behavior on imaging studies. In this context, preoperative imaging plays a crucial role in surgical planning, enabling the surgeon to assess the lesion’s extent, its relationship to adjacent structures, and to tailor a precise and minimally invasive operative approach.

Our surgical approach incorporated a modified hybrid technique originally described by Tayebi Meybodi et al[10], combining extradural and intradural steps for safe and effective decompression of the optic nerve. The primary benefit of our modified approach included the meticulous opening and decompression of the optic nerve dural sleeve, significantly enhancing visualization and ensuring thorough removal of compressive adipose tissue. This adaptation was crucial in achieving complete decompression without compromising adjacent neurovascular structures, likely contributing to the patient’s significant postoperative visual improvement. Such modifications emphasize the importance of technique evolution tailored to anatomical complexities and lesion characteristics, particularly in rare cases like intraosseous lipoma compressing the optic nerve.

This case of intraosseous lipoma of the sphenoid bone compressing the optic nerve in a 41-year-old male highlights the importance of considering rare intraosseous lesions in the differential diagnosis of acute unilateral visual loss. MRI plays an indispensable role in detecting fat-containing lesions and defining their relationship to the optic nerve but cannot, on its own, reliably distinguish intraosseous lipomas from all potential mimics. Definitive management therefore hinges on meticulous surgical decompression and histopathological confirmation. Early recognition and timely optic nerve de

| 1. | Campbell RS, Grainger AJ, Mangham DC, Beggs I, Teh J, Davies AM. Intraosseous lipoma: report of 35 new cases and a review of the literature. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32:209-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Palczewski P, Swiątkowski J, Gołębiowski M, Błasińska-Przerwa K. Intraosseous lipomas: A report of six cases and a review of literature. Pol J Radiol. 2011;76:52-59. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Mafee MF, Goodwin J, Dorodi S. Optic nerve sheath meningiomas. Role of MR imaging. Radiol Clin North Am. 1999;37:37-58, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Murphey MD, Carroll JF, Flemming DJ, Pope TL, Gannon FH, Kransdorf MJ. From the archives of the AFIP: benign musculoskeletal lipomatous lesions. Radiographics. 2004;24:1433-1466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 417] [Cited by in RCA: 384] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Milgram JW. Intraosseous lipomas: radiologic and pathologic manifestations. Radiology. 1988;167:155-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Duarte ML, Pires Penteado Ribeiro D, De Queiroz Pereira Da Silva A, Botelho Alvarenga S, Masson De Almeida Prado JL. Intraosseous lipoma. Medicina (B Aires). 2023;83:1033. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Wiener L, Nassimi D, Clarkson E, Peters SM, Vasilyeva D. Intraosseous spindle cell lipoma of the maxilla: case report and review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2025;54:701-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gangahar CN, Dehner CA, Wang DP, Amini B, Hillen T, O'Conor C, Jennings SN, Byrnes K, Montgomery EA, Czerniak BA, Bridge JA, Schroeder MC, Jennings JW, Wang WL, Chrisinger JSA. Intraosseous hibernoma: clinicopathologic and imaging analysis of 18 cases. Histopathology. 2023;83:40-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sbaraglia M, Bellan E, Dei Tos AP. The 2020 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours: news and perspectives. Pathologica. 2021;113:70-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 664] [Article Influence: 110.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tayebi Meybodi A, Lawton MT, Yousef S, Guo X, González Sánchez JJ, Tabani H, García S, Burkhardt JK, Benet A. Anterior clinoidectomy using an extradural and intradural 2-step hybrid technique. J Neurosurg. 2019;130:238-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/