Published online Jan 16, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i2.116700

Revised: December 13, 2025

Accepted: January 5, 2026

Published online: January 16, 2026

Processing time: 59 Days and 13.2 Hours

Drug-induced liver injury poses a diagnostic challenge in oncology patients, especially those on immune checkpoint inhibitors, because symptoms often ov

We report a case of a 47-year-old woman with metastatic colon cancer on nivo

This case emphasizes the importance of thorough medication history-taking and structured causality assessment to distinguish between unregulated drug-induced liver injury and immune-related adverse events in cancer care. The use of social media to promote alternative therapies necessitates proactive patient counseling due to significant liver risks, and careful diagnostic evaluation can prevent unnecessary immunosuppression or treatment delays.

Core Tip: A middle-aged woman with metastatic colon cancer on immune checkpoint immunotherapy presented with acute hepatocellular injury. This case highlights severe fenbendazole-induced hepatocellular injury in an oncology patient receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors, where timing and causality assessment were vital for accurately attributing the liver injury. Social media-driven self-medication is becoming increasingly common among cancer patients, with fenbendazole doses often far exceeding veterinary recommendations. Prompt recognition and removal of the offending agent can allow safe continuation of immunotherapy and prevent unnecessary immunosuppression. A thorough approach to medication history-taking, including non-prescription and alternative drugs, is essential when evaluating unexplained acute liver injury.

- Citation: Krishnan A, Lucas K, Maas L, Woreta TA. Differentiating fenbendazole-induced liver injury from immunotherapy hepatitis - the importance of structured causality assessment: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(2): 116700

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i2/116700.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i2.116700

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) remains a challenging diagnosis due to its diverse etiologies and clinical presentations[1]. Increasingly, patients are exposed to nonregulated supplements and medications popularized on social media, including veterinary anthelmintics such as fenbendazole, touted anecdotally for anticancer benefits despite lacking robust clinical evidence. Fenbendazole, a veterinary anthelmintic, gained widespread attention after a viral YouTube video featuring Joe Tippens claimed complete remission of metastatic lung cancer following self-administration of fenbendazole while receiving conventional cancer treatments[2]. This video garnered and sparked a phenomenon across multiple social media platforms, now promoting ‘fenben protocols’ to cancer patients worldwide. Among cancer patients using social media for health information, approximately 15%-20% had either used or seriously considered using fenbendazole[3].

Although preclinical studies suggest that fenbendazole may have antineoplastic properties through microtubule disruption, comprehensive animal studies using clinically relevant models have shown no antitumor efficacy[4]. Notably, increased tumor growth with fenbendazole treatment, potentially via the inhibition of connexin 32 and the induction of cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes[5]. Additionally, fenbendazole has been found to worsen acetaminophen-induced liver toxicity in mice by causing persistent glutathione depletion, indicating possible drug interactions and hepatotoxicity risks in humans[6].

Despite anecdotal promotion, its risks may outweigh unproven benefits when self-administered in humans. Severe hepatic adverse effects have been histologically confirmed in limited reports[7,8]. We present a case of severe fen

A 47-year-old woman with a medical history of metastatic colon cancer presented as a direct hospital admission from her outpatient oncology appointment due to one week of nausea, fatigue, dark urine, and abnormal outpatient labs.

The patient reported experiencing one week of nausea, fatigue, dark urine, and jaundice before hospital admission. She was admitted directly to the hospital for further evaluation. She reported minimal alcohol use, approximately one drink per month. She denied using acetaminophen, recent medication changes within the past few months, and any personal or family history of liver disease.

Her medical history includes colon cancer confirmed by biopsy during colonoscopy in 2021, with germline testing showing a MutS homolog 2 variant consistent with Lynch syndrome. The patient later underwent a total colectomy, hysterectomy, and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin. She subsequently developed metastasis in the right peritoneal lymph nodes and underwent laparoscopic omentectomy with adjuvant pembrolizumab therapy. Later, a lung metastasis was identified and treated with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery and left lower lobe wedge resection. Recently, recurrent metastases to the lungs and liver were found on a positron emission tomography scan. The patient had been on nivolumab/relatlimab (Opdualag) for nine months before hospitalization, with her last infusion about four weeks prior to admission.

There was no significant family history of malignancies or known genetic predispositions. She had no history of sign

Symptoms of liver injury, nausea, fatigue, and dark urine began approximately one week before admission, occurring seven days after the fenbendazole dose increase and seven weeks after starting fenbendazole. On physical exam, the patient showed no signs of acute distress; however, mild icterus was observed.

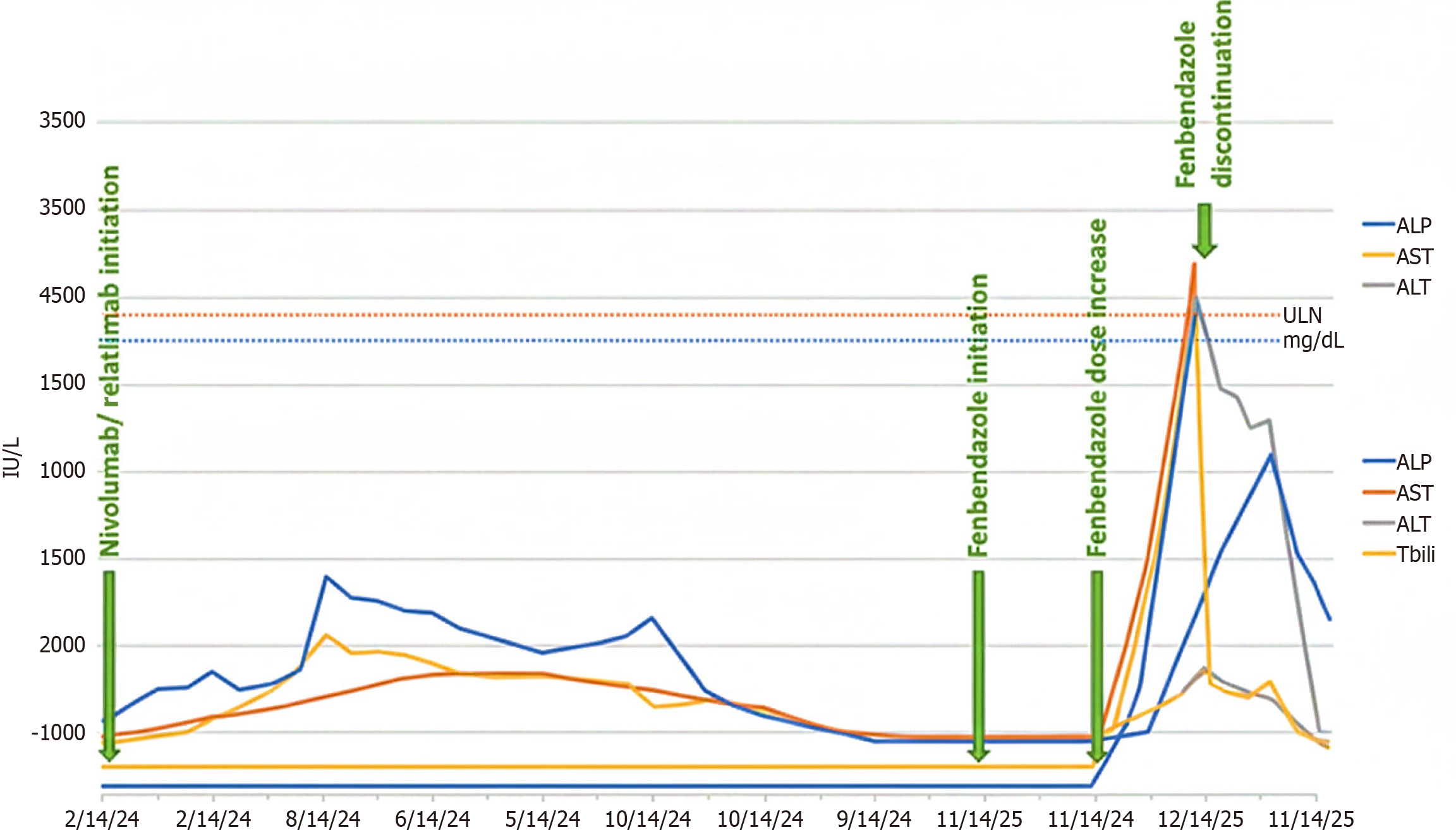

Laboratory results showed a prominent hepatocellular pattern with aspartate aminotransferase at 2435 U/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 2407 U/L, alkaline phosphatase at 215 U/L [upper limit of normal (ULN) 120 U/L], total bilirubin at 3.1 mg/dL, direct bilirubin at 1.75 mg/dL, and international normalized ratio at 1.52. The R ratio [calculated as (ALT/ULN)/(alkaline phosphatase/ULN)] was 11.2, indicating primarily hepatocellular injury. Her baseline liver function tests from the previous month were within normal limits (Figure 1).

The infectious workup was unremarkable, with a normal white blood cell count and negative results on the acute viral hepatitis panel, as well as negative tests for varicella-zoster, Epstein-Barr, and cytomegalovirus. The rest of the serologic workup, including autoimmune hepatitis panel, ceruloplasmin, and human immunodeficiency virus testing, was negative. The acetaminophen level was undetectably low.

A computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast was largely similar to the previous month, although there was possibly slightly increased mild periportal edema, perihepatic and bilateral subdiaphragmatic implants, and scattered lymphadenopathy.

After her negative serologic workup, there was initial concern for ICI hepatitis (ICI-H), given the patient’s receipt of combination nivolumab/relatlimab therapy, with the last dose administered one month prior to admission. However, the presentation was considered atypical, as the onset of ICI-H usually occurs within the first 6-12 weeks after starting therapy.

During the hepatology consultation, the medication history was re-verified in detail. The patient reported that she had started fenbendazole (Panacur C; Merck Animal Health, NJ, United States) approximately eight weeks before admission after consulting a holistic healer who recommended it as an alternative cancer treatment. She initially took 222 mg three times a week for six weeks, then increased to 222 mg daily (1554 mg weekly) two weeks before presentation. She also reported using ‘toxic fungi mold nosode drops’ (12 drops daily) starting at the same time as the dose escalation. While the patient used these homeopathic nosode drops, nosodes lack active pharmaceutical ingredients and are not recognized as hepatotoxins in the medical literature. Additionally, their initiation coincided with fenbendazole dose escalation, making them unlikely to be independent contributors to the acute hepatocellular injury pattern observed.

Applying the Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) yielded a total score of 8, indicating a “probable” likelihood that fenbendazole caused the liver injury[9]. The score was based on factors such as the timing of onset after fenbendazole initiation and dose increase (+2), significant improvement after stopping the drug (+3), exclusion of other causes (+2), the presence of concurrent ICI therapy as a confounder (-1), known reports of hepatotoxicity (+2), and the absence of drug rechallenge (0). This objective assessment supports fenbendazole as the most likely cause of the severe DILI.

This objective assessment supports fenbendazole as the most likely cause of the severe DILI.

The correlation between the timing of the dose increases and symptom onset (7 days apart) strongly suggested that fenbendazole was the cause. Due to spontaneous improvement of liver enzymes during hospitalization after discontinuing fenbendazole, and considering the atypical timing for ICI-H (nine months after initiation, four weeks after the last dose), corticosteroid therapy was withheld, and a liver biopsy was deferred. The patient was advised and counseled to avoid further fenbendazole use.

The patient resumed nivolumab/relatlimab 1 month after discharge, following normalization of her liver function tests, which remained normal after restarting immunotherapy and throughout the subsequent months.

Our case emphasizes the broader public health issue of social media-driven self-medication in oncology. The re

Notably, regulatory agencies such as the United States Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency have issued warnings regarding the off-label use of fenbendazole (and related benzimidazole anthelmintics) for cancer treatment, citing a lack of proven efficacy and a significant risk of liver toxicity. Despite these warnings, self-administration persists worldwide, highlighting the powerful influence of unmoderated social media narratives over official health guidance.

Routine oncology assessments should include proactive, nonjudgmental questions about the use of complementary and alternative medicines, mainly when unexplained laboratory abnormalities occur.

Fenbendazole is a benzimidazole anthelmintic that primarily works by binding to β-tubulin and inhibiting microtubule polymerization. While fenbendazole exhibits 25-fold to 400-fold higher affinity for parasite β-tubulin than mammalian β-tubulin[11], higher doses in humans may exceed this selectivity, disrupting microtubule function in liver cells. Microtubules are crucial for various hepatocellular functions, including bile canalicular transport, protein trafficking, and mitotic spindle formation during hepatocyte regeneration. Disrupting hepatocyte microtubules can impair intracellular trafficking and bile secretion, leading to cholestatic or mixed injury patterns.

Our patient’s dominant hepatocellular pattern (R ratio = 11.2) suggests direct liver cell injury rather than cholestasis. Preclinical studies show that fenbendazole worsens acetaminophen-induced liver damage via persistent hepatic glutathione depletion[6]. Glutathione is an essential antioxidant that protects liver cells from oxidative stress and reactive metabolites. Depleting this defense mechanism can make hepatocytes more susceptible to injury from other medications, metabolic stress, or immune responses.

The mild elevation of total immunoglobulin A (351 mg/dL; reference range 61-348 mg/dL) in our patient may suggest an immune component in the hepatotoxicity. DILI often involves both direct toxicity and immune responses to drug-modified liver proteins. Fenbendazole activates CYP1A1 and CYP1A2, which can generate reactive metabolites or interact with other drugs[6].

The dose-dependent nature of fenbendazole toxicity is explicit in our case: The patient remained asymptomatic during six weeks of low-dose therapy (222 mg three times weekly) but developed severe hepatotoxicity within one week of increasing the dose to daily administration (222 mg daily), which represented a 2.3-fold increase in weekly exposure. This dose-response relationship further supports fenbendazole as the cause.

Differentiating fenbendazole-induced DILI from ICI-H is a significant diagnostic challenge, as both can cause severe hepatocellular injury.

Temporal features: ICI-H usually happens within 6-12 weeks of starting immunotherapy, with a median onset at 8-10 weeks[12]. Late-onset ICI-H (> than 6 months) It is rare, occurring in fewer than 5% of cases. Our patient developed hepatotoxicity 9 months after starting nivolumab/relatlimab and 4 weeks after her last infusion, making ICI-H less likely. Symptom onset 7 weeks after starting fenbendazole and 1 week after dose escalation shows a clear temporal link to the latter drug.

Incidence by immunotherapy type: While combination ICI therapy (e.g., ipilimumab/nivolumab) has a higher risk of hepatitis (approximately of 25%), the nivolumab/relatlimab combination (anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/anti-lymphocyte activation gene 3) has a better liver safety profile. In the RELATIVITY-047 trial, grade 3-4 hepatitis occurred in about 3%-5% of patients on nivolumab/relatlimab, similar to anti-PD-1 monotherapy[13]. Anti-PD-1 monotherapy (nivolumab) is linked to 1%-6% incidence of any-grade hepatitis and 1%-2% of grade 3-4 hepatitis.

Biochemical pattern: Both fenbendazole-induced DILI and ICI-H typically show hepatocellular injury (R ratio > 5). Our patient had an R ratio of 11.2 with peak ALT of 2407 U/L and aspartate aminotransferase of 2435 U/L, consistent with either cause. However, marked elevation of aminotransferases (> 75 × ULN) is more typical of idiosyncratic DILI, while ICI-H often shows more modest elevations [(3-10) × ULN].

Recovery kinetics: DILI usually improves quickly (50% reduction in ALT within 7-14 days) after stopping the drug. ICI-H can last 4-6 weeks despite stopping immunotherapy and often needs corticosteroids for grade 3-4 elevations. A 78% reduction in ALT (from 2407 U/L to 527 U/L) within 10 days of stopping fenbendazole, without corticosteroids, supports DILI over ICI-H.

Rechallenge response: The most substantial evidence comes from successful rechallenge with nivolumab/relatlimab one month after discharge. Liver enzymes normalized before rechallenge and stayed normal after restarting immunotherapy. This argues strongly against ICI-H, as rechallenge with the offending drug usually causes recurrence of hepatotoxicity.

Although a liver biopsy would increase certainty, applying the RUCAM tool yielded a score of 8, placing fen

Although preclinical studies suggest that fenbendazole may have anti-neoplastic properties, no human trials have confirmed its safety or effectiveness. Conversely, the increasing case reports emphasize its potential for causing liver toxicity. This case is particularly novel because fenbendazole-induced DILI closely resembled immune-related hepatitis in an oncology patient receiving combination immunotherapy. Misdiagnosing it early could have led to unnecessary corticosteroid treatment, liver biopsy, and premature discontinuation of immunotherapy. Correctly identifying fen

As more patients use social media-promoted veterinary drugs, clinicians must stay alert, use structured causality tools like RUCAM, and consider unregulated medications when evaluating acute liver injury. To our knowledge, this is the first report illustrating how fenbendazole use can confound clinical assessment of suspected ICI toxicity.

In summary, this case emphasizes the crucial importance of detailed medication history, objective assessment of causality (such as RUCAM), and clinical vigilance regarding unregulated therapies promoted on social media in modern oncology. Fenbendazole-induced DILI can resemble ICI-H, but key differences include the timing of drug exposure, rapid im

| 1. | Hosack T, Damry D, Biswas S. Drug-induced liver injury: a comprehensive review. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2023;16:17562848231163410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kim JH, Oh KH, Shin HY, Jun JK. How cancer patients get fake cancer information: From TV to YouTube, a qualitative study focusing on fenbendazole scandle. Front Oncol. 2022;12:942045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Song B, Kim KJ, Ki SH. Experience with and perceptions of non-prescription anthelmintics for cancer treatments among cancer patients in South Korea: A cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0275620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jung H, Kim SY, Joo HG. Fenbendazole Exhibits Differential Anticancer Effects In Vitro and In Vivo in Models of Mouse Lymphoma. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2023;45:8925-8938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Martarelli D, Pompei P, Baldi C, Mazzoni G. Mebendazole inhibits growth of human adrenocortical carcinoma cell lines implanted in nude mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:809-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gardner CR, Mishin V, Laskin JD, Laskin DL. Exacerbation of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity by the anthelmentic drug fenbendazole. Toxicol Sci. 2012;125:607-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Thakurdesai A, Rivera-Matos L, Nagra N, Busch B, Mais DD, Cave MC. Severe Drug-Induced Liver Injury Due to Self-administration of the Veterinary Anthelmintic Medication, Fenbendazole. ACG Case Rep J. 2024;11:e01354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dougan M, Wang Y, Rubio-Tapia A, Lim JK. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Diagnosis and Management of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Colitis and Hepatitis: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1384-1393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 38.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Danan G, Teschke R. Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method for Drug-Induced Liver Injury: Present and Future. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ng JY, Verhoeff N, Steen J. What are the ways in which social media is used in the context of complementary and alternative medicine in the health and medical scholarly literature? a scoping review. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2023;23:32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dogra N, Kumar A, Mukhopadhyay T. Fenbendazole acts as a moderate microtubule destabilizing agent and causes cancer cell death by modulating multiple cellular pathways. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schneider BJ, Naidoo J, Santomasso BD, Lacchetti C, Adkins S, Anadkat M, Atkins MB, Brassil KJ, Caterino JM, Chau I, Davies MJ, Ernstoff MS, Fecher L, Ghosh M, Jaiyesimi I, Mammen JS, Naing A, Nastoupil LJ, Phillips T, Porter LD, Reichner CA, Seigel C, Song JM, Spira A, Suarez-Almazor M, Swami U, Thompson JA, Vikas P, Wang Y, Weber JS, Funchain P, Bollin K. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:4073-4126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 1343] [Article Influence: 268.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tawbi HA, Schadendorf D, Lipson EJ, Ascierto PA, Matamala L, Castillo Gutiérrez E, Rutkowski P, Gogas HJ, Lao CD, De Menezes JJ, Dalle S, Arance A, Grob JJ, Srivastava S, Abaskharoun M, Hamilton M, Keidel S, Simonsen KL, Sobiesk AM, Li B, Hodi FS, Long GV; RELATIVITY-047 Investigators. Relatlimab and Nivolumab versus Nivolumab in Untreated Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:24-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 1355] [Article Influence: 338.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/