Published online Nov 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i33.112305

Revised: September 3, 2025

Accepted: October 23, 2025

Published online: November 26, 2025

Processing time: 115 Days and 23.8 Hours

Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is a rare autoimmune bleeding disorder characterized by autoantibodies against coagulation factor VIII (FVIII), leading to spon

We present the case of a 65-year-old male with a history of hypopharyngeal squa

This case underscores vigilance for AHA after head and neck cancer therapy to enable prompt treatment.

Core Tip: We report a unique case of acquired hemophilia A, an autoimmune bleeding disorder due to factor VIII (FVIII) autoantibodies, occurring after head and neck cancer surgery and chemoradiotherapy—a previously unreported association. A 65-year-old male developed recurrent hemoptysis, diagnosed by prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time and high-titer FVIII inhibitors. Intensive immunosuppressive therapy achieved sustained six-year remission, demonstrating the critical role of timely diagnosis and aggressive management for this severe therapy-related complication.

- Citation: Zhao PW, Hu YS, Jiang Z, Ainiwaer M, Liu J, Chen F. Recurrent hemoptysis after laryngectomy-acquired hemophilia induced by laryngeal cancer surgery and chemoradiotherapy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(33): 112305

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i33/112305.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i33.112305

Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is a rare but potentially life-threatening bleeding disorder caused by the development of autoantibodies against coagulation factor VIII (FVIII), leading to its functional deficiency[1]. The incidence of AHA is approximately 1.5 cases per million individuals annually[1]. While about 50% of cases are idiopathic, the remaining are associated with conditions such as autoimmune diseases, malignancies, and postpartum states. AHA has been recognized as a paraneoplastic syndrome, with FVIII inhibitors developing in association with tumors and surgical interventions[2]. Although AHA secondary to malignancies is well-documented[3], our thorough literature review found no previously reported cases of AHA specifically developing in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma following extensive surgery and concomitant chemoradiotherapy. Herein, we present a unique case of AHA manifesting as hemoptysis and extensive ecchymosis after treatment for hypopharyngeal carcinoma, highlighting a previously unrecorded complication.

A 65-year-old male presented to the emergency department with recurrent episodes of hemoptysis.

Upon re-admission, coagulation studies revealed isolated prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) of 83.8 seconds. The APTT mixing test failed to correct the prolongation. Further evaluation showed markedly reduced FVIII activity (< 1%; reference range: 60%–150%) and a high-titer FVIII inhibitor at 18.4 Bethesda units. Tests for lupus anticoagulant (dilute Russell's viper venom time) and anticardiolipin antibodies were negative. Given the absence of personal or family history of hemophilia A, a diagnosis of AHA was established.

One year prior, the patient was diagnosed at our institution with hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (T4bN2cM0, AJCC 8th edition), involving the epiglottic cartilage, left aryepiglottic fold, left piriform sinus, left carotid sheath, left posterior cervical triangle, bilateral submandibular spaces, and enlarged lymph nodes in both supraclavicular fossae. Preoperative APTT was within normal limits at 27.4 seconds (reference range: 24.8–33.8 seconds). He underwent ex

Personal hemoptysis: The patient has no smoking history and drinks alcohol occasionally. He has an unremarkable social history and denies any history of intravenous drug use or illicit substance abuse.

Family hemoptysis: There is no family history of genetic diseases reported. The patient's family history is negative for heritable conditions among first-degree relatives.

The patient presented with mild hemoptysis, expelling small blood clots that were self-limiting. Due to the recurrent, intermittent nature of the bleeding and the admixture of blood with respiratory secretions, precise quantification of the hemoptysis volume was not feasible. There were no accompanying symptoms such as abdominal pain, distension, significant cough, sputum production, or dyspnea. Laryngoscopy revealed diffuse mucosal oozing without a single identifiable bleeding point, and physical examination showed no hemorrhage points in the pharynx and no palpable masses in the neck.

The diagnosis was made based on severely reduced FVIII activity and the confirmed presence of a FVIII inhibitor (18.4 Bethesda Units). The normalization and subsequent overshoot of FVIII activity following immunosuppressive therapy is a hallmark of successful treatment in AHA (Table 1).

| Time point | FVIII activity result | Clinical significance |

| At diagnosis (upon readmission) | < 1% (reference range: 60%–150%) | Confirmed the diagnosis of acquired hemophilia A |

| End of therapy (follow-up) | 188.2% | Confirmed complete remission, indicating successful treatment and cure |

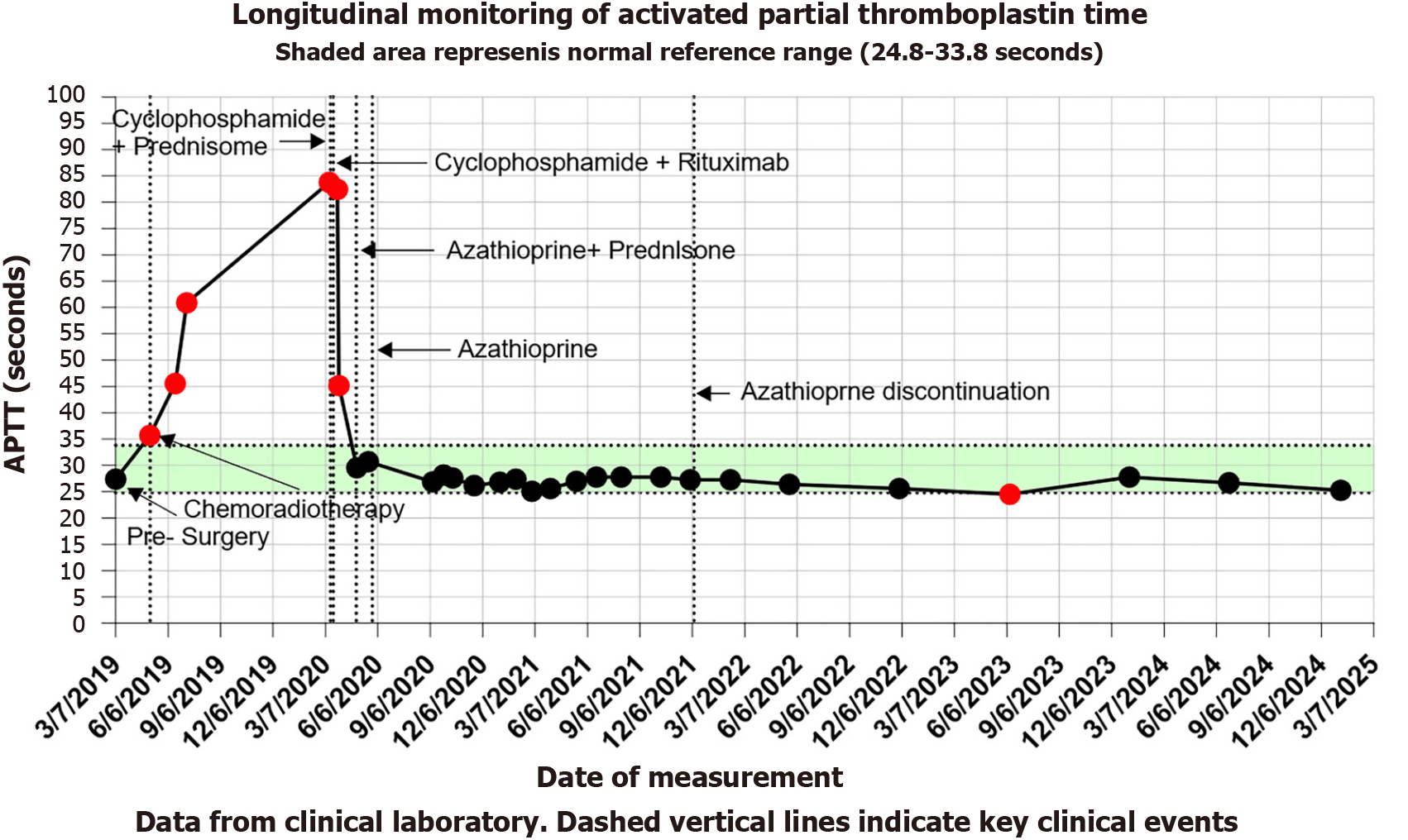

The line graph (Figure 1) illustrates the trends in APTT levels during the patient’s disease progression. The green shaded area denotes the normal reference range, and red dots indicate abnormal values. Key clinical milestones are annotated: Preoperative status (January 7, 2019), initiation of chemoradiotherapy (May 6, 2019), and immunosuppressive therapy for AHA beginning on March 8, 2020 (Cyclophosphamide + Prednisone). Subsequent regimen adjustments included: Cyclophosphamide + Prednisone (March 30, 2020), Azathioprine + Prednisone (April 29, 2020), discontinuation of Prednisone (May 27, 2020; monotherapy with Azathioprine), and cessation of Azathioprine (December 1, 2021). Notably, APTT levels stabilized within the normal range following the initiation of AHA-directed immunosuppressive therapy.

All coagulation assays were performed at our hospital's clinical laboratory. The APTT was measured using a silica-based reagent on an automated coagulation analyzer. The APTT mixing study was conducted following standard protocol, incubating the patient's plasma with normal pooled plasma (1:1 ratio) for 2 hours before re-assaying the APTT. Factor VIII activity (FVIII: C) was determined using a one-stage, factor-deficient plasma-based clotting assay. The FVIII inhibitor titer was quantified using the Nijmegen-Bethesda assay. Lupus anticoagulant was tested using the dilute Russell's viper venom time test, and anticardiolipin antibodies were detected by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

No imaging studies are available for this case.

AHA.

The therapeutic approach focused on hemostasis and inhibitor eradication. Hemostatic management with tranexamic acid and batroxobin effectively controlled bleeding. Initial immunosuppressive therapy comprised prednisone (1 mg/kg/day) and cyclophosphamide (1.5 mg/kg/day) for four weeks. Due to the development of hematemesis, the regimen was modified to cyclophosphamide combined with rituximab. The patient's bleeding symptoms improved significantly. After one month, the treatment was adjusted to azathioprine and prednisone. Prednisone was discontinued after another month, and azathioprine was tapered based on APTT results until cessation (Figure 1). Follow-up tests showed normalization of APTT and FVIII activity (188.2%).

The patient achieved complete remission from AHA with the normalization of coagulation parameters. To vigilantly monitor for potential tumor recurrence, a rigorous, multi-modal follow-up protocol was implemented for over six years. This protocol included: Morphological surveillance with annual contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the neck and thorax. This was critical for assessing deep-tissue structures and regional lymph nodes for any signs of recurrence or metastasis. Endoscopic evaluation performed biannually (every six months). Each examination consisted of: Conventional white-light laryngoscopy to directly visualize the mucosal surfaces of the operative site and pharynx. Narrow-band imaging laryngoscopy to enhance the detection of abnormal vascular patterns suggestive of early neoplastic changes, which might be imperceptible under white light alone. Immunosuppressive therapy with azathioprine was successfully discontinued on December 8, 2021. Since then, the patient has had no further bleeding episodes, and his factor VIII activity has remained supranormal (> 180%). Throughout this entire follow-up period, all endoscopic and imaging examinations have shown no evidence of local recurrence or distant metastasis.

This case report has several strengths, including the detailed longitudinal documentation of the patient's clinical course with a comprehensive timeline (Figure 1), and the long-term follow-up period of six years which clearly demonstrates the efficacy of the treatment and the durability of remission. However, our findings must be interpreted in the context of the inherent limitations of a single case report. The observations and conclusions are based on one individual, which limits the generalizability of our results. Furthermore, the retrospective nature of the analysis may introduce potential biases in data collection and interpretation. Despite these limitations, we believe this case provides valuable insights into a rare but serious complication.

AHA is an uncommon bleeding disorder characterized by the sudden development of autoantibodies against FVIII, leading to its functional deficiency. It is associated with various conditions, including autoimmune diseases, mal

Paraneoplastic syndromes are a group of disorders triggered by a cancerous tumor but not caused by the direct effects of the tumor mass or its metastases. They occur when the immune system, in its response to the tumor, or due to substances released by the tumor, inadvertently attacks normal cells. In the context of AHA, it is considered a paraneoplastic phenomenon wherein the underlying malignancy disrupts immune homeostasis and leads to a loss of self-tolerance. This dysregulated immune response results in the production of autoantibodies that mistakenly target coagulation factor VIII, culminating in the clinical manifestations of AHA[4]. The temporal relationship in our patient, where coagulation abnormalities emerged following cancer treatment, strongly supports the hypothesis that AHA was a paraneoplastic event triggered by the malignancy and its subsequent therapy.

Furthermore, we propose that the major surgical intervention itself played a direct 'triggering' role in the pathogenesis. Extensive tissue trauma from surgery leads to the release of a substantial load of intracellular antigens into the circulation[5], antigens that are typically shielded from the immune system. In a host with an already compromised or dysregulated immune system, such as our patient with malignancy and a history of chemoradiotherapy, this acute exposure to a flood of self-antigens can break immune tolerance. This process may occur through the presentation of previously 'cryptic' epitopes of FVIII or via molecular mimicry, activating autoreactive lymphocytes and culminating in the production of anti-FVIII autoantibodies[6]. Therefore, the surgical trauma likely acted as a 'second hit' that unmasked the clinical presentation of AHA on the underlying background of a paraneoplastic syndrome.

The diagnostic approach to AHA involves identifying isolated prolonged APTT, performing mixing studies to distinguish between factor deficiencies and inhibitors, measuring FVIII activity, and quantifying inhibitor titers using the Bethesda assay[7,8]. In this case, the diagnostic process adhered to established guidelines, effectively ruling out other potential causes such as lupus anticoagulant.

Management of AHA centers on controlling bleeding and eradicating inhibitors. Hemostatic agents include bypassing agents like recombinant activated FVII and activated prothrombin complex concentrates, as well as FVIII concentrates and antifibrinolytics[7,8]. Given the patient's mild bleeding manifestations, tranexamic acid and batroxobin were sufficient. Immunosuppressive therapy is crucial for inhibitor eradication, with first-line treatments comprising corticosteroids alone or in combination with cyclophosphamide[7,8]. Rituximab is considered in cases where first-line therapy is ineffective or contraindicated[7,8]. In this patient, the initial regimen was modified due to gastrointestinal bleeding, and subsequent therapy with cyclophosphamide and rituximab proved effective. Maintenance therapy with azathioprine and prednisone facilitated sustained remission.

This case highlights the necessity of considering AHA in patients with head and neck malignancies who develop unexplained bleeding and prolonged APTT, particularly following surgical and chemoradiotherapeutic.

This case illustrates a rare but critical complication of AHA following multimodality therapy for advanced head and neck cancer. The temporal association between extensive surgical resection, subsequent chemoradiotherapy, and the development of FVIII inhibitors suggests a paraneoplastic mechanism potentially triggered by tissue trauma and immune dysregulation. The diagnosis of AHA should be considered in any patient with unexplained bleeding and isolated prolonged APTT, particularly in the context of recent oncologic treatment. Early recognition, appropriate hemostatic management, and prompt initiation of immunosuppressive therapy are essential for achieving remission. Importantly, this patient maintained long-term remission from both AHA and malignancy over six years, demonstrating the efficacy of a tailored immunosuppressive regimen and vigilant follow-up. This report underscores the need for heightened clinical awareness of AHA as a possible late adverse event in head and neck cancer patients undergoing aggressive treatment.

We sincerely thank the patient for providing consent to publish his case details. We also thank the anonymous reviewer for his/her insightful comments which greatly improved the manuscript.

| 1. | Zanon E. Acquired Hemophilia A: An Update on the Etiopathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Reitter S, Knoebl P, Pabinger I, Lechner K. Postoperative paraneoplastic factor VIII auto-antibodies in patients with solid tumours. Haemophilia. 2011;17:e889-e894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Reeves BN, Key NS. Acquired hemophilia in malignancy. Thromb Res. 2012;129 Suppl 1:S66-S68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Napolitano M, Siragusa S, Mancuso S, Kessler CM. Acquired haemophilia in cancer: A systematic and critical literature review. Haemophilia. 2018;24:43-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lai B, Wu CH, Wu CY, Luo SF, Lai JH. Ferroptosis and Autoimmune Diseases. Front Immunol. 2022;13:916664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Münz C, Lünemann JD, Getts MT, Miller SD. Antiviral immune responses: triggers of or triggered by autoimmunity? Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:246-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tiede A, Collins P, Knoebl P, Teitel J, Kessler C, Shima M, Di Minno G, d'Oiron R, Salaj P, Jiménez-Yuste V, Huth-Kühne A, Giangrande P. International recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of acquired hemophilia A. Haematologica. 2020;105:1791-1801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 42.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Thrombosis and Hemostasis Group; Chinese Society of Hematology Chinese Medical Association; Hemophilia Treatment Center Collaborative Network of China. [Chinese guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of acquired hemophilia A (2021)]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2021;42:793-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/