Published online Nov 6, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i31.110734

Revised: July 9, 2025

Accepted: September 11, 2025

Published online: November 6, 2025

Processing time: 139 Days and 9.9 Hours

Post-polypectomy syndrome (PPS) is a rare but relevant complication of endo

We report the case of a 67-year-old man who presented with asthenia and abdo

This case highlights the importance of accurate endoscopic diagnosis and te

Core Tip: Although therapeutic colonoscopy is generally safe, it may be associated with significant complications. This case illustrates how post-polypectomy syndrome can mask a colonic perforation with subsequent abscess formation. It em

- Citation: Suárez M, Martínez R, Santiago-Ramos PC. Not losing sight of the bigger picture of complications associated with post-polypectomy syndrome: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(31): 110734

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i31/110734.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i31.110734

Colonoscopy is an increasingly utilized and well-established procedure, now regarded as nearly routine. Its role has expanded beyond disease diagnosis to become a cornerstone in the detection and prevention of colorectal cancer (CRC)[1,2]. The ability to simultaneously diagnose precancerous CRC lesions and other mucosal abnormalities in the colon and in the ileum when intubated, along with the possibility to perform therapeutic interventions during the same session, has contributed to its growing use and broader acceptance.

Technological advances in endoscopes and the improvements in endoscopic techniques have significantly enhanced the diagnostic capability of this procedure. The development and widespread adoption of high-definition endoscopes and enhanced imaging systems, particularly chromoendoscopy, together with the use of devices designed to improve mucosal visualization, such as caps, and the recent introduction of artificial intelligence, have improved both the sensitivity and specificity of endoscopic diagnosis[3-5].

These diagnostic advances are complemented by therapeutic innovations, making colonoscopy a procedure capable of both diagnosis and treatment in a single session. The development of dedicated cold-snare polypectomy devices which allow resection of polyps without the need for electrocautery, together with improvements in the electrosurgical current characteristics when diathermy is required, allow the removal of almost all lesions practically restricting surgical resections to invasive lesions[6,7]. Furthermore, the improvement of hemoclips for prophylaxis of delayed bleeding has facilitated the resection of increasingly larger and more complex lesions[8].

In addition to all the advancements, the most important is the increased patient acceptance of undergoing colonoscopy. Split-dose bowel preparations, widespread use of sedation, and the application of CO2 insufflation for colonic distension have all contributed to improved tolerance and acceptance among the general population[9-11].

Despite all the positive advances in colonoscopy, it remains a procedure not without risks as with every invasive test. Although the overall complication rate is generally below 1%[12], adverse events still occur and must be acknowledged and communicated to patients. We present a clinical case illustrating several of these complications and their management.

A 67-year-old male presented to the emergency department with asthenia, abdominal pain, and general discomfort following a scheduled colonoscopy with polypectomy.

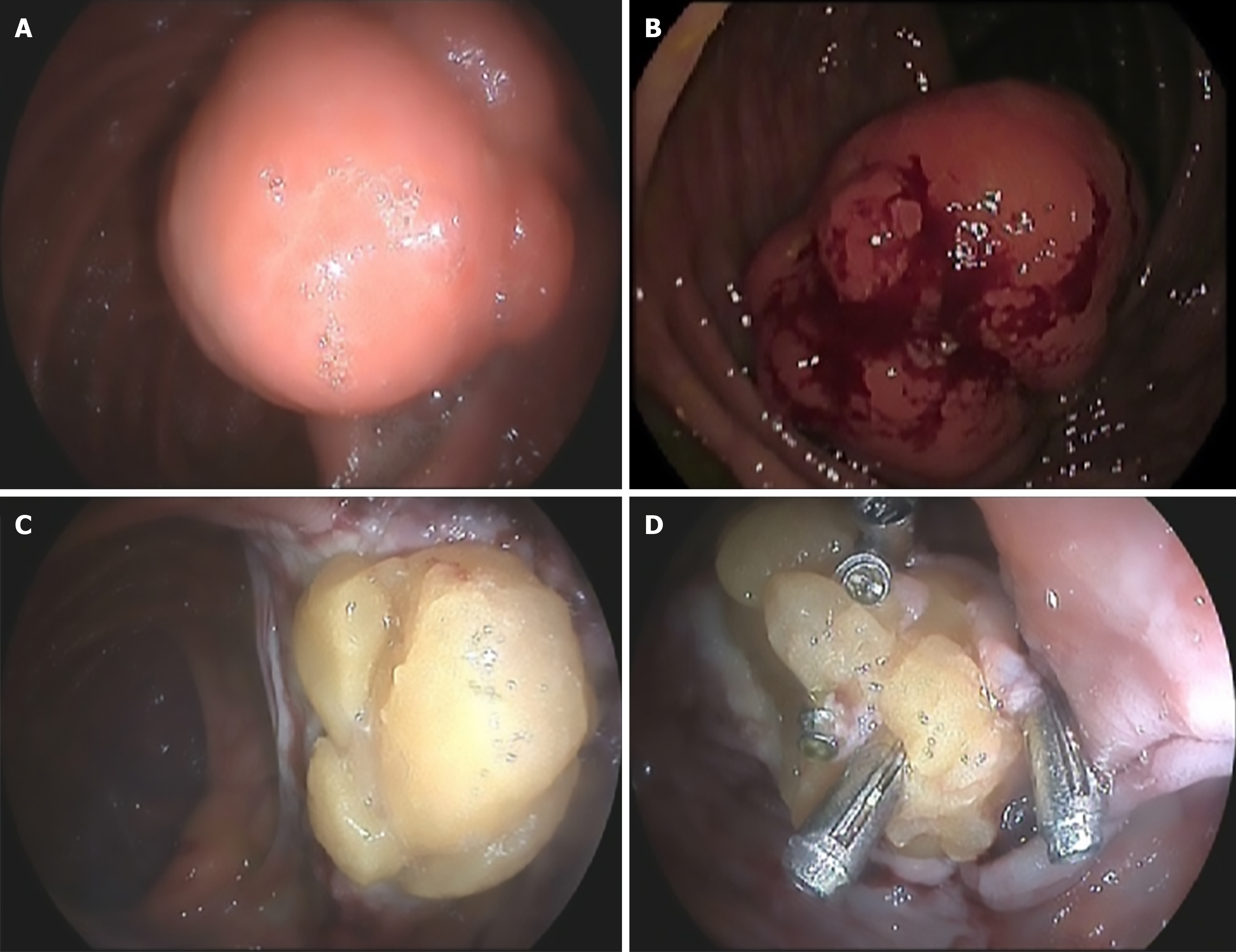

The patient underwent a scheduled therapeutic colonoscopy following an initial endoscopy as part of the CRC screening program. During this second endoscopy, a 5 cm lesion with slight surface ulceration located in the right colon and no cushion sign was resected without immediate complications (Figure 1). The defect revealed fat tissue attached to the colonic wall, precluding successful closure with standard endoscopic clips.

After the procedure, the patient experienced mild abdominal pain and a low-grade fever (37.8 ºC) measured at home. These symptoms were managed by his primary care physician under the diagnosis of post-polypectomy syndrome (PPS). No signs of bleeding or peritoneal irritation were reported. Given the patient’s personal circumstances as the primary caregiver for his wife, this conservative approach was chosen.

Following this episode, the patient reported a 14-day course of progressive fatigue without any overt bleeding or abdominal pain. Despite ongoing contact with his primary care physician throughout this period, no symptoms were reported until the patient developed dyspnea on minimal exertion and abdominal pain. Consequently, the patient was referred to the emergency department of our institution.

His medical history was notable for former smoking, approximately 10 cigarettes per day, having quit around 5 years prior. He also had a history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus, both managed with oral medication.

The patient reported no other relevant personal or family medical history.

Upon arrival at the emergency department, the patient presented good general condition but exhibited mucocutaneous pallor. Blood pressure was 147/78 mmHg, and heart rate was 111 beats per minute. Physical examination revealed tenderness on palpation in the right iliac fossa without signs of peritoneal irritation. Digital rectal examination showed no evidence of blood.

In the emergency department, the patient presented with hemoglobin levels of 8.3 g/dL and a hematocrit of 25.4%. No coagulopathy was detected. As acute phase reactants, the white blood cell count was 10900/mm3 with 74.3% neutrophils, fibrinogen levels were 565 mg/dL, and C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated at 108.9 mg/L.

Once admitted to the ward, after transfusion of one unit of packed red blood cells, hemoglobin levels increased to 9.4 g/dL, with a parallel improvement in hematocrit. The remaining parameters remained stable.

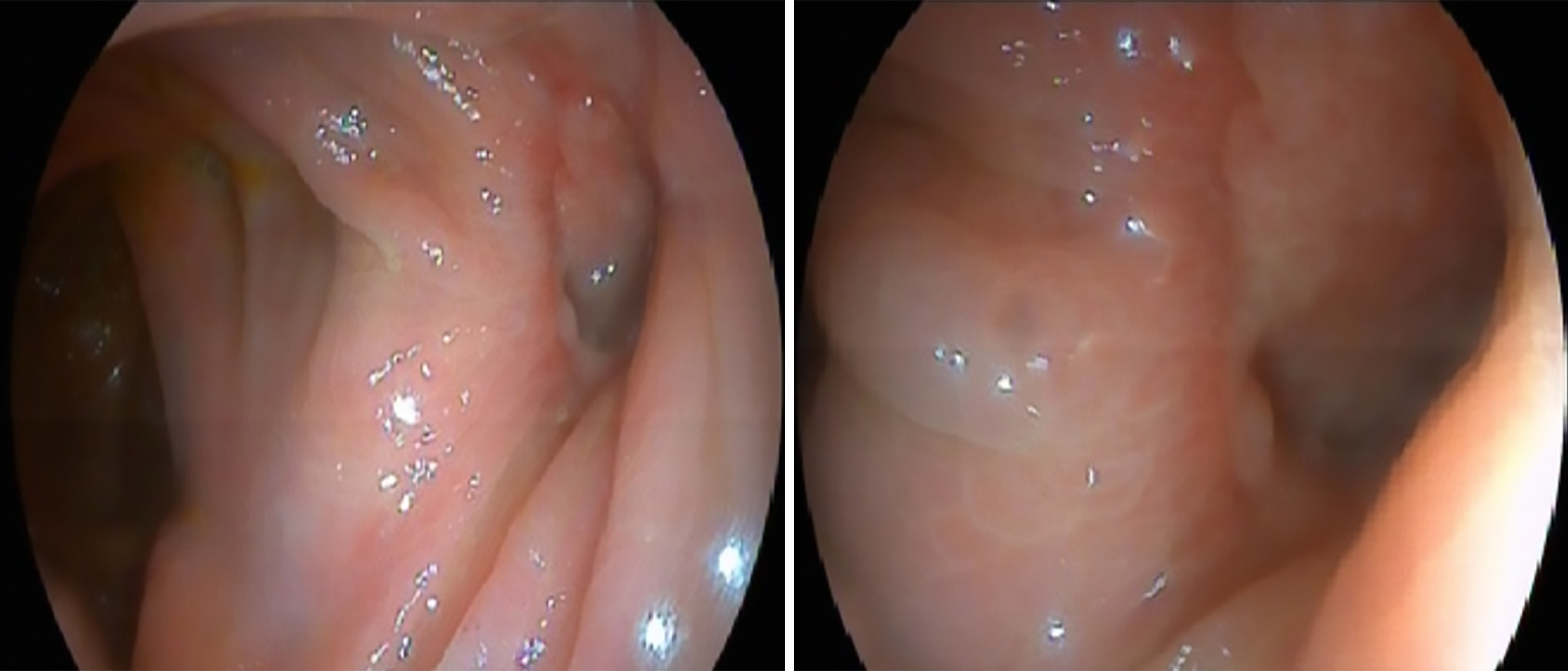

Initially, the case was approached as a possible post-polypectomy hemorrhage given the presence of anemia. Therefore, a repeat colonoscopy was performed, which revealed no active bleeding and only showed a post-polypectomy scar without evidence of drainage (Figure 2).

In the absence of significant findings, an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained. The TC revealed a 9 cm × 9.5 cm × 3 cm collection adjacent to the right colon with intralesional gas bubbles, consistent with an abscess secondary to colonic perforation (Figure 3).

Initially, the patient was diagnosed with PPS secondary to colonic polyp resection. During hospitalization, the diagnosis was revised to an intra-abdominal collection secondary to colonic microperforation. Histopathological analysis of the resected lesion revealed a submucosal lipoma, which could explain the sequence of events.

After the diagnosis, a surgical consultation was requested. Conservative management with antibiotic therapy and drainage of the collection was recommended. Empirical antibiotic treatment with Piperacillin/Tazobactam was initiated. The abscess was drained using an 8 French catheter, which was maintained for one week while the patient was kept on nothing per os (NPO) and received parenteral nutritional support. Cultures grew Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, both susceptible to the administered antibiotics. The drainage catheter was kept in place for 10 days with local care and irrigation, leading to the resolution of the collection. The patient was subsequently discharged on a 14-day course of oral Amoxicillin/Clavulanate. The percutaneous drain was removed at the patient’s primary care center after drainage had ceased, within three weeks of its placement.

The patient was followed for one year with multiple imaging studies, including abdominal ultrasound and CT scans, which showed no evidence of recurrent collections. Laboratory tests during follow-up revealed no significant abnormalities, with normalization of hemoglobin levels. Informed consent was obtained during the first consultation.

Separately, the patient was admitted under the care of the Cardiology department due to exertional angina without anemia. He was diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy with myocardial fibrosis, attributed to a previous myocardial infarction. Coronary angiography revealed a critical chronic occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending artery requiring placement of a drug-eluting stent. Left ventricular ejection fraction improved from 30% to 40% following medical therapy and cardiac rehabilitation.

To visually summarize the clinical case, a timeline has been created and is presented in Table 1.

| Date | Event |

| March | Positive FIT result |

| April | Initial colonoscopy: Large lesion identified in the right colon |

| May | Scheduled therapeutic colonoscopy |

| May | Two days post-colonoscopy: Diagnosis of PPS |

| June | Referred to the emergency department. Hospital admission |

| July | Favorable outcome. Discharged from hospital |

| August | Outpatient follow-up. Asymptomatic. No abscess detected on ultrasound |

| After one year with five follow-up visits, discharged from the Gastroenterology Department | |

As previously mentioned, colonoscopy is a very safe procedure, with complications fortunately being infrequent. It is considered a quality criterion that the complication rate remains below 1% for hemorrhage and under 0.1% for perforations among all colonoscopies performed[3]. This clinical case illustrates several errors and complications arising from a therapeutic procedure.

The first issue was the initial optical diagnosis. The absence of high-resolution endoscopes at the time of the procedure, combined with the atypical morphology of the lesion and the indirect pressure exerted by the patient’s positive fecal occult blood test, led to the erroneous resection of a benign lesion using an inappropriate technique. Colonic lipomas are lesions arising from submucosal adipose tissue, generally asymptomatic and usually smaller than 2 cm[13]. Although the literature describes various complications associated with large lipomas, such as altered bowel habits, abdominal pain, bleeding, and even intussusception, these occurrences are relatively rare[14,15].

In the presented case, the lesion could be considered complicated (bleeding) due to the positive fecal immunochemical test attributed to suspected ulceration on its surface. However, given the available resources at that time, the resection technique employed was not optimal. It is important to consider that, as a submucosal lesion, the risk of perforation is significantly increased compared to mucosal lesions. An attempt was made to close the defect using through-the-scope (TTS) clips. This proved insufficient and the defect remained open. Adequate closure of the post-polypectomy defect was hindered by the fat tissue associated with the lipoma, the limited size of the TTS clips, and their insufficient compressive force. Closure with an over-the-scope (OTS) clip to achieve full-thickness closure of the colonic wall or resection using advanced techniques such as endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), endoscopic full-thickness resection, or submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection at a referral center would have been optimal approaches in this clinical scenario to avoid a right hemicolectomy[16-18].

Subsequently, the patient developed PPS or transmural burn syndrome. This syndrome is an infrequent complication occurring in less than 0.1% of polypectomies resulting from the removal of colonic lesions, typically involving the use of electrocautery. The underlying pathophysiological mechanism consists of a transmural thermal injury to the intestinal wall without perforation leading to serosal inflammation and secondary signs of peritoneal irritation, although these are not always present. Clinical manifestations can appear from hours after the procedure up to five days of post-examination. The most common symptoms include fever, focused abdominal pain or possible peritoneal irritation, leukocytosis, and elevated CRP levels in laboratory tests[19,20]. Risk factors for its development include polyp size, location (cecum), and the use of diathermy, although an increasing number of cases have been reported with cold snare polypectomy[21-23]. Treatment consists of bowel rest, antipyretics, and antibiotics to prevent bacterial translocation[24].

In our case, the initial management appeared appropriate given the correct identification of the most probable diagnosis. Furthermore, the patient’s personal circumstances, being the primary caregiver for his wife, and the considerable distance to the nearest hospital (over 100 km) made the chosen approach reasonable under this situation. Ideally, blood tests and imaging studies should have been performed at that time to confirm the diagnosis and rule out perforation, which was unfortunately confirmed later. The patient was followed by his primary care physician, who identified the complication arising from the colonoscopy as well as making the initial diagnosis of PPS.

Due to the patient’s progressive clinical deterioration, he was referred to the emergency department. A more serious complication than PPS was suspected. These colonoscopy-related complications might have been detected earlier through blood tests during follow-up or if the patient had been able to be transferred to the emergency department at the time of the initial diagnosis. The presence of anemia on laboratory testing, combined with progressive asthenia and dyspnea, initially raised suspicion of post-polypectomy bleeding (PPB).

PPB is the most common complication following endoscopic resection. It is defined as bleeding occurring at the site of polypectomy after the procedure. It may present as immediate or delayed bleeding up to 30 day), with clinical manifestations varying in the extent of bleeding and whether the source is arterial or venous. Presentations range from mild rectorrhagia or hematochezia to massive hemorrhage with hemodynamic instability. Risk factors include advanced age, cardiovascular comorbidities, use of antiplatelet or anticoagulant agents, lesion size, morphology, and location, among others described in the literature[25-27].

Management strategies have evolved over time. Traditionally, colonoscopy was performed in most cases, regardless of clinical presentation or hemodynamic impact. Currently, a more individualized approach is favored, with endoscopy being deferred in cases without hemodynamic instability, significant anemia (hemoglobin drop > 2 g/dL), or other risk factors such as an ASA anesthetic risk score ≥ III[28,29]. In the present case, this clinical suspicion would have been more plausible if the patient showed any evidence of overt bleeding. Notably, no active bleeding or blood residue was identified during the colonoscopy.

If there is one particularly feared complication following colonoscopy, it is perforation. While the acceptable perforation rate is considered to be less than 0.1% for diagnostic procedures, it may increase to up to 1% following polypectomy[3,30]. Furthermore, rates as high as 1.5% have been reported in cases involving large lesions or ESD[20]. However, these figures should be interpreted with caution as most are derived from retrospective studies conducted prior to the widespread use of current advanced technologies.

As shown in Figure 1 during the therapeutic endoscopy, an attempt was made to close the wall defect using clips. In the follow-up colonoscopy performed due to suspicion of PPB, an orifice was observed at the site of the previous polypectomy scar. This finding corresponded to a perforation caused during the initial procedure, although it was not interpreted this way (Figure 2). In other words, although appropriate measures were taken during the first colonoscopy, they were insufficient to prevent this complication. This was due to the subepithelial nature of the lesion. The preventive approach should have involved deeper wall closure rather than merely attempting to close the mucosal defect. The use of OTS clips or the suture systems currently available on the market could have achieved the closure[31]. Closure of the defect, even at a later stage, might have helped the clinical management of the patient.

In addition to the perforation, the patient developed an intra-abdominal collection adjacent to the site of the injury. Notably, the patient remained largely asymptomatic despite the size of the collection and the positive cultures for E. coli and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Given its size and proximity to the abdominal wall, percutaneous drain was placed by interventional radiology. Depending on the location of such lesions, management may range from surgical intervention to conservative treatment with antibiotics alone, particularly when the collection measures less than 3 cm[32,33]. In this case, the collection resolved alongside the perforation, without the need for further invasive procedures.

In summary, this clinical case underscores the importance of thorough diagnostic evaluation prior to endoscopic resection. While the initial management was appropriate and justified given the patient’s clinical context, closer follow-up with laboratory or imaging studies might have facilitated an earlier diagnosis of the complication. The sequential development of PPS, colonic perforation with abscess formation, and the potential for delayed bleeding highlights that these complications should not be viewed as mutually exclusive but rather as part of a possible clinical continuum following polypectomy. The implementation of advanced resection and closure techniques, combined with individualized, risk-based procedural planning, may substantially reduce the incidence of such adverse events and improve patient outcomes.

Moreover, this case highlights the critical role of accurate optical diagnosis in the initial assessment of colorectal lesions. Careful characterization of polyps prior to resection is essential for guiding therapeutic decisions and anticipating potential risks. Even in patients with complex clinical backgrounds, it is crucial to clearly communicate the possibility of complications and to insist on appropriate post-procedural evaluation, even if this implies a slight delay in decision-making. The lessons learned from this case emphasize the need for vigilance, structured follow-up, and a multidisciplinary approach to avoid preventable adverse outcomes. By integrating these principles into routine practice, future cases may benefit from improved safety, better patient education, and more effective complication management.

Colonoscopy is a safe and well-tolerated procedure and remains a cornerstone in the prevention of CRC and the diagnosis of other gastrointestinal diseases. However, it is not free of risks and potential complications must be clearly understood. This case highlights how PPS can obscure more serious complications, such as colonic perforation with abscess formation. The appropriate selection of resection and closure techniques, along with close clinical monitoring following the procedure, is critical to minimizing the risk of severe complications. Moreover, this case emphasizes that a multidisciplinary approach and early intervention can help avoid surgical treatment and reduce patient morbidity.

We would like to acknowledge the support of the Virgen de la Luz Hospital and the Bayer Chair in Artificial Intelligence (University of Castilla-La Mancha) for their involvement and encouragement during the development of this work.

| 1. | Rex DK. Colonoscopy Remains an Important Option for Primary Screening for Colorectal Cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2025;70:1595-1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Li J, Li ZP, Ruan WJ, Wang W. Colorectal cancer screening: The value of early detection and modern challenges. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:2726-2730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rex DK. Key quality indicators in colonoscopy. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2023;11:goad009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Galati JS, Lin K, Gross SA. Recent advances in devices and technologies that might prove revolutionary for colonoscopy procedures. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2023;20:1087-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hsu WF, Chiu HM. Optimization of colonoscopy quality: Comprehensive review of the literature and future perspectives. Dig Endosc. 2023;35:822-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ferlitsch M, Hassan C, Bisschops R, Bhandari P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Risio M, Paspatis GA, Moss A, Libânio D, Lorenzo-Zúñiga V, Voiosu AM, Rutter MD, Pellisé M, Moons LMG, Probst A, Awadie H, Amato A, Takeuchi Y, Repici A, Rahmi G, Koecklin HU, Albéniz E, Rockenbauer LM, Waldmann E, Messmann H, Triantafyllou K, Jover R, Gralnek IM, Dekker E, Bourke MJ. Colorectal polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2024. Endoscopy. 2024;56:516-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 76.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Marín-Gabriel JC, Romito R, Guarner-Argente C, Santiago-García J, Rodríguez-Sánchez J, Toyonaga T. Use of electrosurgical units in the endoscopic resection of gastrointestinal tumors. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:512-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nomura T, Sugimoto S, Temma T, Oyamada J, Ito K, Kamei A. Suturing techniques with endoscopic clips and special devices after endoscopic resection. Dig Endosc. 2023;35:287-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pan H, Zheng XL, Fang CY, Liu LZ, Chen JS, Wang C, Chen YD, Huang JM, Zhou YS, He LP. Same-day single-dose vs large-volume split-dose regimens of polyethylene glycol for bowel preparation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10:7844-7858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Anderson JC, Kahi CJ, Sullivan A, MacPhail M, Garcia J, Rex DK. Comparing adenoma and polyp miss rates for total underwater colonoscopy versus standard CO(2): a randomized controlled trial using a tandem colonoscopy approach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:591-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sidhu R, Turnbull D, Haboubi H, Leeds JS, Healey C, Hebbar S, Collins P, Jones W, Peerally MF, Brogden S, Neilson LJ, Nayar M, Gath J, Foulkes G, Trudgill NJ, Penman I. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on sedation in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gut. 2024;73:219-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Kim SY, Kim HS, Park HJ. Adverse events related to colonoscopy: Global trends and future challenges. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:190-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 13. | Jacobson BC, Bhatt A, Greer KB, Lee LS, Park WG, Sauer BG, Shami VM. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Gastrointestinal Subepithelial Lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:46-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fiordaliso M, Lovaglio UM, De Marco FA, Costantini R, Nasti GA, Lelli Chiesa P. Colonic lipoma, a rare cause of intestinal intussusception: A narrative review and how to diagnose it. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103:e39579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bacha D, Kammoun N, Mallek I, Gharbi L, Lahmar A, Slama SB. Pedunculated colonic lipoma causing adult colo-colic intussusception: A case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2024;123:110242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee JM, Kim JH, Kim M, Kim JH, Lee YB, Lee JH, Lim CW. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of a large colonic lipoma: Report of two cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3127-3131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mavrogenis G, Bazerbachi F, Tsevgas I, Zachariadis D. Endoscopic submucosal dissection and submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection for obstructive lipomas of the foregut and hindgut. VideoGIE. 2019;4:226-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhou P, Cai M, Elkholy S. Endoscopic Resection of Submucosal Lesions of the Upper GI Tract: Full-Thickness Resection (EFTR) and Submucosal Tunneling Resection (STER). In: Testoni PA, Inoue H, Wallace MB, editors. Gastrointestinal and Pancreatico-Biliary Diseases: Advanced Diagnostic and Therapeutic Endoscopy. Cham: Springer, 2021. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Hirasawa K, Sato C, Makazu M, Kaneko H, Kobayashi R, Kokawa A, Maeda S. Coagulation syndrome: Delayed perforation after colorectal endoscopic treatments. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:1055-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 20. | Kaltenbach T, Anderson JC, Burke CA, Dominitz JA, Gupta S, Lieberman D, Robertson DJ, Shaukat A, Syngal S, Rex DK. Endoscopic Removal of Colorectal Lesions: Recommendations by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:435-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fusco S, Bauer ME, Schempf U, Stüker D, Blumenstock G, Malek NP, Werner CR, Wichmann D. Analysis of Predictors and Risk Factors of Postpolypectomy Syndrome. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024;14:127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hong HS, Yang DH. Postpolypectomy syndrome after cold snare endoscopic mucosal resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95:590-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Núñez-Pizarro JL, Luzko I, Rivero-Sánchez L. Postpolypectomy syndrome after multiple cold-snare polypectomies in the rectum. Dig Endosc. 2023;35:928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cha JM, Lim KS, Lee SH, Joo YE, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim HG, Park DI, Kim SE, Yang DH, Shin JE. Clinical outcomes and risk factors of post-polypectomy coagulation syndrome: a multicenter, retrospective, case-control study. Endoscopy. 2013;45:202-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Albéniz E, Pellisé M, Gimeno García AZ, Lucendo AJ, Alonso Aguirre PA, Herreros de Tejada A, Álvarez MA, Fraile M, Herráiz Bayod M, López Rosés L, Martínez Ares D, Ono A, Parra Blanco A, Redondo E, Sánchez Yagüe A, Soto S, Díaz Tasende J, Montes Díaz M, Téllez MR, García O, Zuñiga Ripa A, Hernández Conde M, Alberca de Las Parras F, Gargallo C, Saperas E, Navas MM, Gordillo J, Ramos Zabala F, Echevarría JM, Bustamante M, González Haba M, González Huix F, González Suárez B, Vila Costas JJ, Guarner Argente C, Múgica F, Cobián J, Rodríguez Sánchez J, López Viedma B, Pin N, Marín Gabriel JC, Nogales Ó, de la Peña J, Navajas León FJ, León Brito H, Remedios D, Esteban JM, Barquero D, Martínez Cara JG, Martínez Alcalá F, Fernández Urién I, Valdivielso E; en nombre del Grupo Español de Resección Endoscópica de la Sociedad Española de Endoscopia Digestiva. Clinical guidelines for endoscopic mucosal resection of non-pedunculated colorectal lesions. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:175-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhang X, Jiang X, Shi L. Risk factors for delayed colorectal postpolypectomy bleeding: a meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rodríguez de Santiago E, Hernández-Tejero M, Rivero-Sánchez L, Ortiz O, García de la Filia-Molina I, Foruny-Olcina JR, Prieto HMM, García-Prada M, González-Cotorruelo A, De Jorge Turrión MA, Jiménez-Jurado A, Rodríguez-Escaja C, Castaño-García A, Outomuro AG, Ferre-Aracil C, de-Frutos-Rosa D, Pellisé M; Endoscopy Group of the Spanish Gastroenterology Association. Management and Outcomes of Bleeding Within 30 Days of Colonic Polypectomy in a Large, Real-Life, Multicenter Cohort Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:732-742.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sengupta N, Feuerstein JD, Jairath V, Shergill AK, Strate LL, Wong RJ, Wan D. Management of Patients With Acute Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding: An Updated ACG Guideline. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:208-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 38.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (33)] |

| 29. | Rodríguez de Santiago E, Pérez de la Iglesia S, de Frutos D, Marín-Gabriel JC, Mangas-SanJuan C, Honrubia López R, Uchima H, Aicart-Ramos M, Rodríguez Gandía MÁ, Valdivielso Cortázar E, Ramos Zabala F, Álvarez MA, Solano Sánchez M, González Santiago JM, Albéniz E, Hijos-Mallada G, Castro Quismondo N, Fraile-López M, Martínez Ares D, Tejedor-Tejada J, Hernández L, Gornals JB, Quintana-Carbo S, Ocaña J, Cunha Neves JA, Martínez Martínez J, López-Cerón Pinilla M, Dolz Abadía C, Pellisé M. Delphi consensus statement for the management of delayed post-polypectomy bleeding. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2025;18:17562848251329145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Elmunzer BJ, Anderson MA, Mishra G, Rex DK, Yadlapati R, Shaheen NJ. Quality Indicators Common to All Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Procedures. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119:1781-1791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gala K, Brunaldi V, Abu Dayyeh BK. Novel Devices for Endoscopic Suturing: Past, Present, and Future. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2024;34:733-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Expert Panel on Interventional Radiology, Weiss CR, Bailey CR, Hohenwalter EJ, Pinchot JW, Ahmed O, Braun AR, Cash BD, Gupta S, Kim CY, Knavel Koepsel EM, Scheidt MJ, Schramm K, Sella DM, Lorenz JM. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Radiologic Management of Infected Fluid Collections. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:S265-S280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ierardi AM, Lanza C, Calandri M, Filippiadis D, Ascenti V, Carrafiello G. ESR Essentials: image guided drainage of fluid collections-practice recommendations by the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe. Eur Radiol. 2025;35:1034-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/