Published online Nov 6, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i31.110624

Revised: July 18, 2025

Accepted: August 25, 2025

Published online: November 6, 2025

Processing time: 141 Days and 21 Hours

Acute liver failure (ALF) due to diffuse hepatic infiltration by metastatic mela

A 61-year-old male presented with jaundice, abdominal distension, and encephalopathy. Liver imaging suggested acute Budd-Chiari syndrome, and liver trans

Infiltrative melanoma should be considered in unexplained ALF, even without previously known malignancy.

Core Tip: Acute liver failure (ALF) due to diffuse hepatic infiltration by metastatic melanoma is an exceptionally rare and often misdiagnosed entity, especially in patients without a known history of malignancy. This case highlights the importance of considering infiltrative malignancy in unexplained ALF, even when initial imaging suggests vascular etiologies such as Budd-Chiari syndrome. Liver biopsy remains essential for accurate diagnosis and may alter transplant eligibility. Early recognition and histopathologic confirmation are critical for guiding appropriate clinical decisions in this rapidly fatal presentation.

- Citation: Domislovic V, Sesa V, Kosuta I, Bulimbasic S, Mrzljak A. Liver failure due to metastatic melanoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(31): 110624

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i31/110624.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i31.110624

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a life-threatening condition characterized by sudden and severe impairment of hepatic function, coagulopathy, and hepatic encephalopathy in individuals without pre-existing liver disease[1]. While drug-induced liver injury, viral hepatitis, and autoimmune hepatitis are common causes, malignancy-associated ALF remains exceedingly rare[2]. Among these, metastatic melanoma represents an especially uncommon etiology, with only isolated cases reported in the literature.

Melanoma has a known predilection for hepatic metastasis; however, clinical manifestations of liver involvement are often silent or subtle until disease burden progresses. Infiltration of the hepatic parenchyma by melanoma cells can lead to rapid liver decompensation, and in rare cases, present as ALF.

Here, we present a case of a 61-year-old male who developed ALF secondary to diffuse hepatic infiltration by mel

| Ref. | Clinical presentation | History of cancer | Diagnosis method of liver disease | Treatment | Outcome |

| Current case | Diffuse abdominal pain, jaundice, hepatic encephalopathy; progressive ALF with multi-organ dysfunction | No prior cancer history; possible uveal melanoma based on visual symptoms; no autopsy | Liver biopsy; HMB-45-positive melanoma | Supportive ICU care (intubation, dialysis, vasopressors); considered for transplant until result of biopsy | Death on day 7 |

| O’Neill et al[3], 2024 | RUQ pain, myalgia, nausea, subjective fevers; fulminant ALF | Previously excised cutaneous melanoma (in situ) on upper back, 1 year prior | Histopathological diagnosis via core biopsy of left axillary lymph node (MART1, SOX10, HMB45-positive) | Dual immunotherapy (nivolumab + ipilimumab), IV terlipressin, ICU support | Death on day 17 post-presentation due to refractory encephalopathy and hepatorenal syndrome |

| Lee et al[4], 2022 | Nausea, vomiting, RUQ and LUQ pain, dyspepsia; fulminant ALF | No known history of melanoma; presumed first presentation, later verified suspicious skin lesions | Liver biopsy (S-100, HMB45, MART1-positive); stomach biopsy supportive | Supportive care; no specific antitumor therapy reported | Death shortly after liver biopsy; multiple organ failure before workup for primary site completed |

| Schlevogt et al[7], 2017 | Right flank pain; rapid deterioration to ALF with renal failure and encephalopathy | Malignant melanoma of right flank (3 years prior), recurrent cutaneous metastases; colorectal carcinoma resected 6 months prior | Liver biopsy (S100-positive; HMB45/MART1-negative) | BRAF-inhibitor (Vemurafenib) + MEK-inhibitor (Cobimetinib) | Death after one week 7 days; autopsy confirmed diffuse hepatic infiltration |

| Escobar-Valdivia et al[5], 2017 | RUQ pain, jaundice, weight loss, blindness in left eye; rapid ALF with encephalopathy | Undiagnosed uveal (choroidal) melanoma; visual impairment to blindness over 2 months, history revealed pigmented eye lesion 1 year prior | Post-mortem histopathology (liver and eye); coagulopathy precluded biopsy ante-mortem | Supportive care (FFP, vitamin K); no tumor-directed therapy | Death from multiorgan failure 4th in-hospital day; confirmed metastatic uveal melanoma on autopsy |

| Tanaka et al[11], 2015 | Left hand necrotic ulcer, erythema on trunk, no encephalopathy; later developed ALF | No known history of melanoma; diagnosed post-mortem as melanoma of unknown primary origin | Post-mortem histopathology and immunohistochemistry (HMB-45, S100-positive) | Palliative care; patient not eligible for systemic therapy due to poor performance status | Death on day 47; diffuse hepatic and splenic infiltration by melanoma confirmed on autopsy |

| Mashayekhi et al[12], 2014 | Jaundice, abdominal pain, oliguria; rapid ALF with multiorgan failure | Suspicious skin lesion (mole on back) noted 10 days before admission, not yet diagnosed or treated | Post-mortem histopathology; liver, heart, lung, kidney, bladder infiltrated with melanoma | Supportive care (antibiotics, fluids, inotropes); no tumor-directed therapy before death | Death on day 3; widespread multiorgan metastatic melanoma confirmed on autopsy |

| Bellolio et al[10], 2013 | Abdominal pain, jaundice, acholic stools, dark urine; rapid progression to fulminant hepatic failure | History of breast cancer treated 5 years prior; no known melanoma | Post-mortem histopathology; liver, spleen, and lymph nodes infiltrated with melanoma; HMB-45 and S-100-positive | Supportive care; rapid deterioration precluded biopsy or targeted therapy | Death shortly after admission; melanoma of unknown primary confirmed at autopsy |

| Tanaka et al[13], 2004 | Malaise, anorexia, abdominal distension, edema; ALF and encephalopathy, death within hours | No prior history; melanoma of unknown primary origin diagnosed post-mortem | Post-mortem histopathology; massive hepatic infiltration, melanoma cells in mesenteric lymph nodes | Supportive care only; rapid deterioration precluded therapeutic intervention | Death on hospital day 7; massive liver involvement, no primary site found on autopsy |

| Montero et al[8], 2002 | Jaundice, nausea, vomiting, general malaise; ALF with encephalopathy and renal failure | Supraciliary melanoma treated 18 months prior (Clark II, < 1 mm depth, negative margins) | Transjugular liver biopsy; diffuse sinusoidal infiltration by melanoma, HMB-45-positive | Standard liver failure therapy; no antitumor intervention | Death on day 10; progressive hepatic encephalopathy and renal dysfunction |

| Te et al[6], 1999 | Nausea, vomiting, RUQ pain, malaise; fulminant hepatic failure with encephalopathy and renal failure | Scalp lesion biopsied 2 months prior; initially non-diagnostic, later confirmed as melanoma | Percutaneous liver biopsy (HMB-45, S-100-positive); scalp mass re-biopsy-confirmed melanoma | Supportive therapy; chemotherapy deferred due to rapid deterioration | Death within 24 hours of encephalopathy onset; extensive sinusoidal infiltration confirmed histologically |

| Bouloux et al[9], 1986 | Hypochondrial pain, nausea, vomiting, jaundice, encephalopathy; rapid onset ALF and hepatorenal syndrome | Previously treated nodular melanoma (Clark IV, 5 mm depth) of right scapula; in situ melanoma of sacrum | Post-mortem histopathology; liver almost entirely replaced by melanoma, confirmed microscopically | Supportive care (vitamin K, neomycin, lactulose); no tumor-specific therapy given | Death on day 10; diffuse liver infiltration confirmed on autopsy |

A 61-year-old male was transferred to a tertiary transplant center due to clinical deterioration in terms of impaired consciousness, abdominal pain with marked distension, and jaundice.

Two weeks prior, the patient began experiencing symptoms of abdominal pain, progressive abdominal distension and jaundice for which he was admitted to a local hospital. Due to worsening liver injury and declining consciousness, the patient was referred to a tertiary transplant center.

The patient’s past medical history was significant for hypertension and dyslipidemia, which were both well-controlled with medication. He did not have a medical history of liver disease prior to hospitalization.

The patient had no relevant family history.

The patient’s hemodynamic and respiratory status remained stable, but he exhibited somnolence (Glasgow Coma Scale 11, West Haven Grade 3), indicating a decreased level of consciousness. Physical examination revealed jaundice, tense, non-tender abdominal distension, and a palpably enlarged liver. The patient showed no cutaneous signs of chronic liver disease (e.g., spider angiomata, palmar erythema).

Initial laboratory tests revealed hepatocellular liver injury (alanine transaminase [ALT] 500 IU/mL, aspartate transaminase [AST] 800 IU/mL, alkaline phosphatase 230 IU/mL, gamma-glutamyl transferase 350 IU/mL), elevated bilirubin (total 200 μmol/L, indirect 90 μmol/L, direct 110 μmol/L), and impaired liver synthetic function (international norma

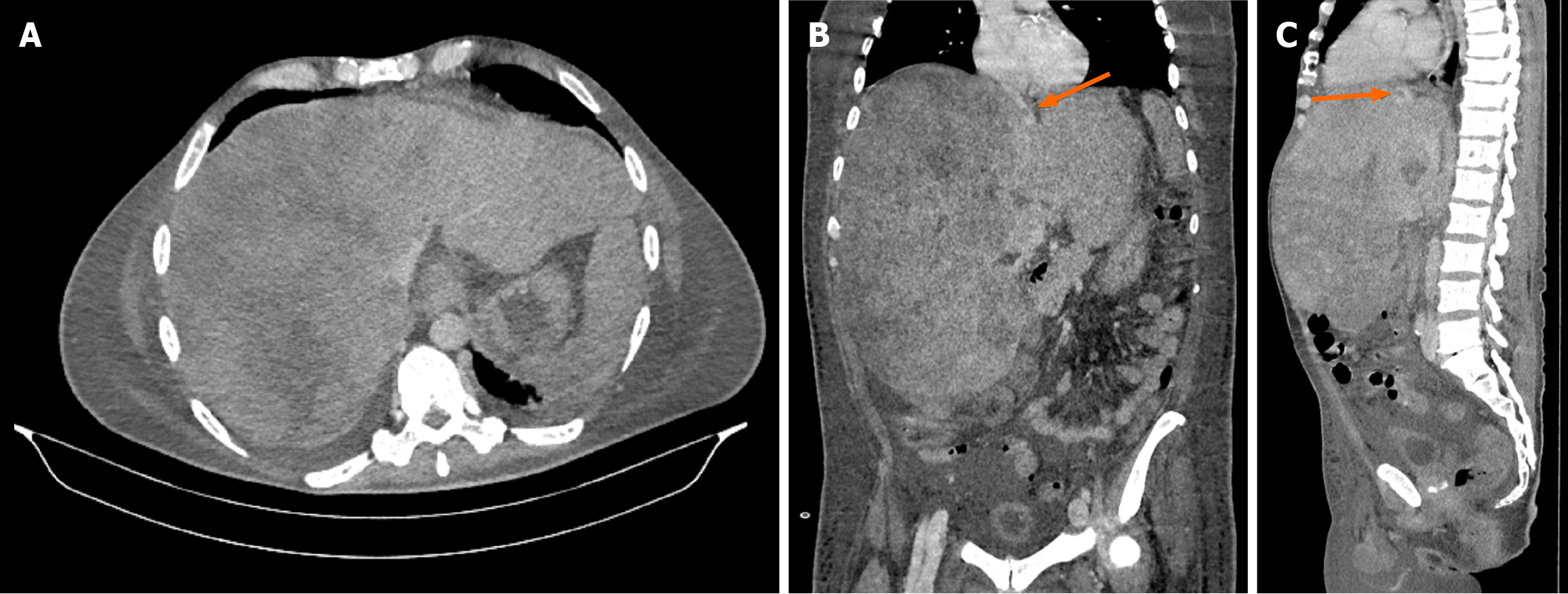

Ultrasound examination showed hepatomegaly (liver size up to 28 cm in the midclavicular line) with a heterogeneous liver parenchyma, splenomegaly (longitudinal diameter 140 mm), and a small amount of free fluid. A multiphase contrast-enhanced multislice computed tomography (MSCT) revealed a markedly enlarged liver (32 cm × 25 cm × 31 cm) occupying almost the entire abdomen and displacing surrounding organs (Figure 1A and B). The liver parenchyma was described as very heterogeneous. Both the right and middle hepatic veins were completely compressed with absent blood flow, and thrombosis was observed in the left hepatic vein (Figure 1C). The inferior vena cava was obliterated in the intrahepatic portion up to the confluence of the renal veins. A small amount of ascites and splenomegaly was also noted.

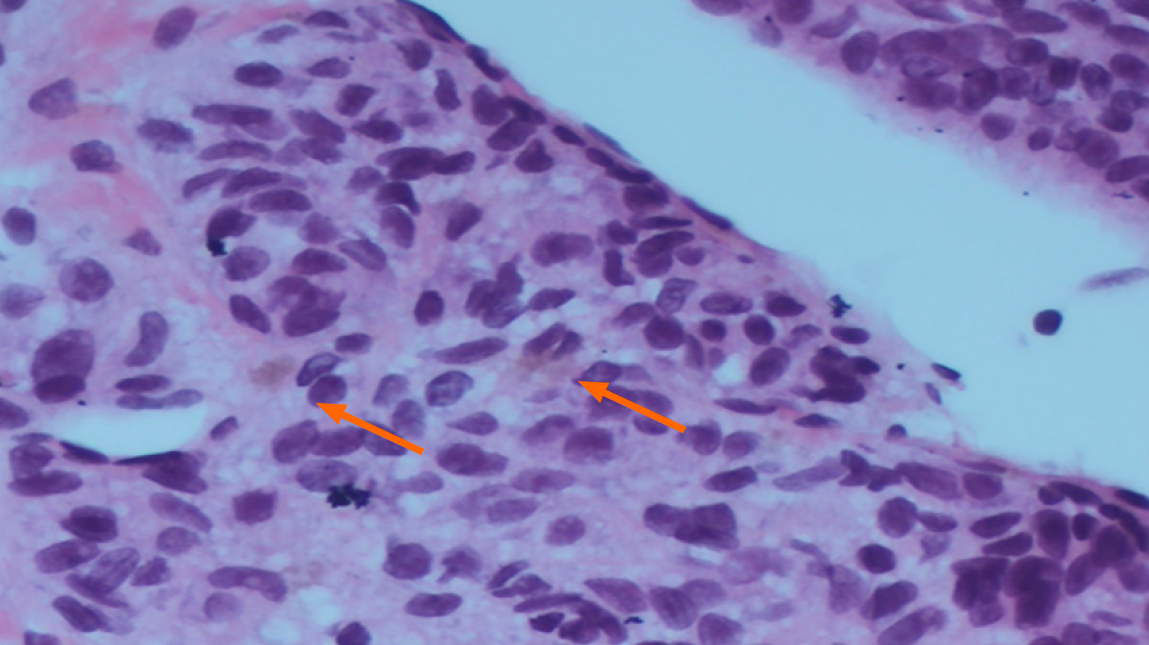

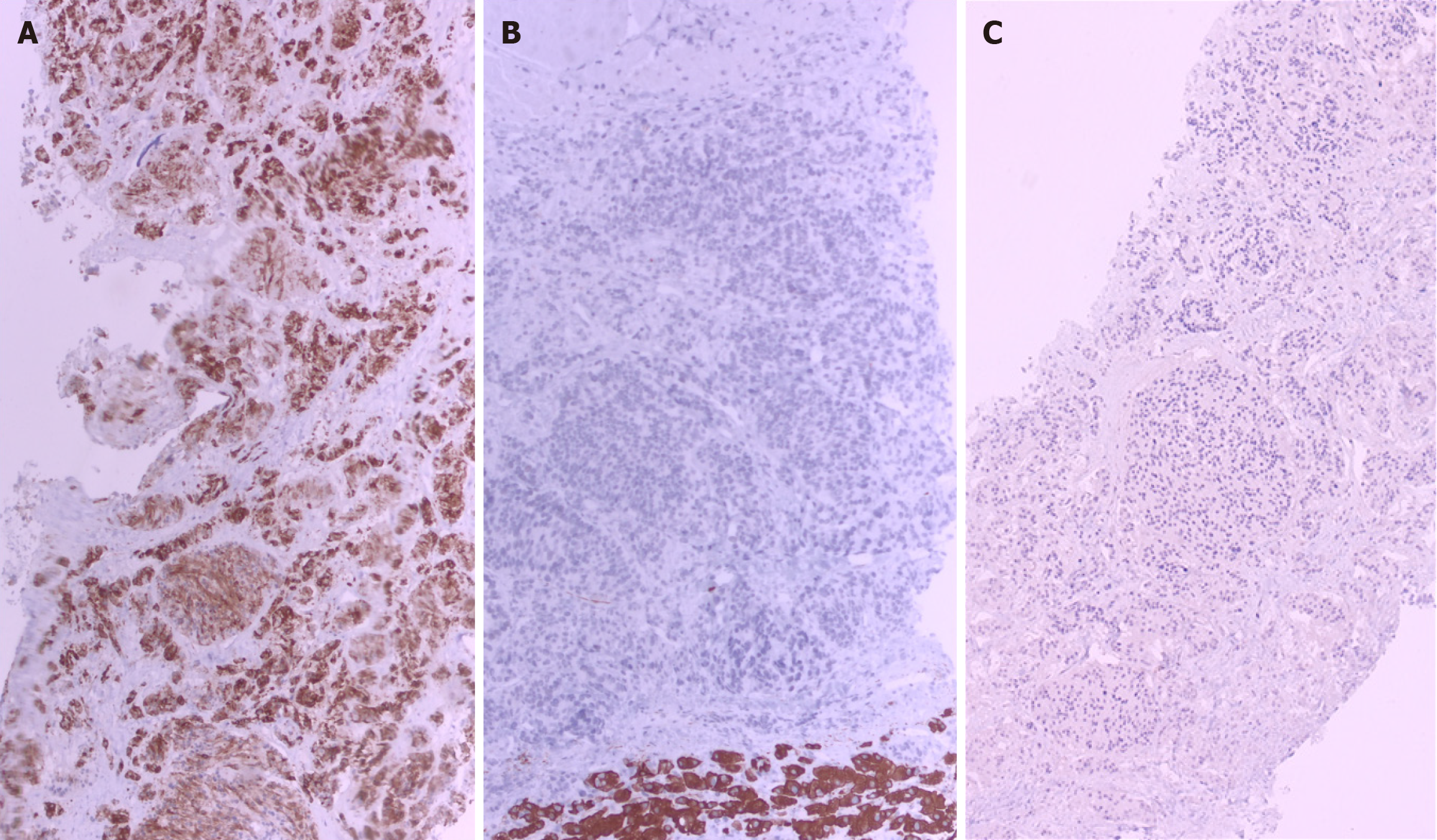

To rule out infiltrative liver disease, a percutaneous liver biopsy was performed under ultrasound guidance after preprocedural optimization. Initially, transjugular approach was considered but after consultation with an interventional radiologist, this approach was deemed technically unfeasible due to radiologically confirmed thrombosis and obliteration of the hepatic veins as well as the inferior vena cava. Histopathological examination revealed a sparse amount of normal liver parenchyma, with the remainder of the biopsy consisting of a necrotic tumor infiltrate composed of clusters and short strands of atypical, oval to spindle-shaped cells, with polymorphic nuclei and prominent nucleoli (Figure 2). Individual tumor cells and areas of necrosis were accompanied by scant yellow-brown pigment. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were diffusely positive for human melanoma black (HMB-45) and negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and Discovered On Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor 1, confirming the diagnosis of infiltrative melanoma (Figure 3).

The patient was discussed by the multidisciplinary team for liver transplantation consisting of transplant hepatologists, infectious disease specialists, intensive care specialists, surgeons, radiologists, anesthesiologists, and pathologists. Given the patient's clinical deterioration and progressive liver failure, liver transplantation due to ALF was considered a potential treatment option; therefore, urgent pre-transplantation workup was initiated. Meanwhile, after confirming melanoma in the liver biopsy, the decision for liver transplant was contraindicated.

Based on clinical, laboratory, radiological and pathohistological findings, the patient was diagnosed with metastatic melanoma as the underlying cause of ALF.

The patient's clinical condition worsened, with the development of sopor and oliguria (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] 30 mL/min/1.72 m2) and further elevation in liver enzymes (ALT 2110 IU/mL, AST 1900 IU/mL), with per

The patient succumbed to ALF on the fourth day of hospital admission. Further discussion with the family revealed a history of visual disturbances in the left eye at 1 month prior, raising suspicion of a uveal melanoma as the primary site of the malignancy. Unfortunately, the patient’s family denied a medical request for autopsy, and the primary site remained undetermined.

Our patient presented with progressive abdominal pain, jaundice, and hepatic encephalopathy, manifestations consistent with fulminant hepatic failure as a result of metastatic melanoma of unknown primary origin. A 40-year literature review yielded 11 cases with similar presentations, often including initial non-specific symptoms such as nausea, malaise, right upper quadrant pain, and jaundice[3-6]. However, in several cases such as those by Escobar-Valdivia et al[5] and Te et al[6], ocular or dermatological signs (e.g., vision loss or skin lesions) preceded hepatic symptoms, potentially offering earlier diagnostic clues. These clinical presentations underline the deceptive onset of liver failure in patients with melanoma, which often lacks initial dermatologic or systemic warning signs, complicating timely diagnosis. The initial ambiguity of symptoms also contributes to misdiagnosis or delayed recognition. Our case initially presented as acute Budd-Chiari syndrome based on radiologic findings, further illustrating the clinical overlap with other hepatologic emergencies. This could lead to a diagnostic dilemma, necessitating a broader diagnostic approach, including a liver biopsy.

In our case, there was no documented prior history of malignancy, although post-mortem discussion revealed recent visual disturbances, raising suspicion of a uveal melanoma as the primary site. This contrasts with several other cases where patients had previously diagnosed melanomas, cutaneous or ocular, that were either excised or under surveillance[3,7-9]. Notably, some cases involved previously undetected or misdiagnosed lesions, such as in Lee et al[4], where suspicious skin changes were only noted retrospectively, and one case involved a patient with prior breast cancer, but without known melanoma[10]. The variable presence or absence of cancer history demonstrates the diagnostic challenge and the necessity of maintaining a high index of suspicion even in patients without known malignancy. This aspect is particularly relevant in the transplant setting, where identifying occult malignancy could alter management plans significantly. In our patient, the lack of prior oncological history initially supported transplant eligibility until liver biopsy results necessitated a change in course of treatment.

Our patient’s laboratory findings demonstrated profound liver dysfunction: Markedly elevated transaminases (ALT up to 2110 IU/L, AST up to 1900 IU/L), rising bilirubin (to 190 μmol/L), coagulopathy (INR 3.5), hypoglycemia, lactic aci

Radiologic imaging in our case revealed an enlarged liver with heterogeneous enhancement, compression of the hepatic veins, and features suggestive of Budd-Chiari syndrome, without described focal liver lesion. These findings were initially misleading, highlighting the diagnostic overlap between vascular obstruction and infiltrative malignancies. Similar radiological patterns have been reported in other cases, including hepatomegaly, diffuse hypodensity, and lack of focal lesions despite extensive tumor infiltration[4,6,11]. The non-specific nature of these imaging findings often delays definitive diagnosis. While cross-sectional imaging such as contrast-enhanced CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is valuable in evaluating structural abnormalities and ruling out other causes, clinicians should be aware of potential dis

Diagnosis in our case was confirmed via percutaneous liver biopsy, revealing extensive infiltration by HMB-45-positive melanoma cells. This aligns with several other reports where liver biopsy, transjugular or percutaneous, was pivotal for diagnosis[3,6-7]. However, in multiple instances, diagnosis was made postmortem due to either clinical instability or rapid deterioration that precluded biopsy[5,9-13]. Immunohistochemistry remains essential, with markers such as HMB-45, S100, and melanoma antigen recognized by T cells aiding in confirming melanocytic origin. These findings underscore the critical role of timely liver biopsy in unexplained liver failure.

In patients with ALF and significant coagulopathy, transjugular liver biopsy is generally considered the safer diagnostic approach, as it minimizes the risk of intraperitoneal hemorrhage and allows simultaneous hemodynamic assessment of the hepatic circulation. By contrast, percutaneous biopsy can provide larger cores of parenchyma but carries a higher bleeding risk, particularly in the setting of hepatomegaly or ascites[14]. In our case, however, transjugular liver biopsy was technically impossible due to complete thrombosis and obliteration of the hepatic veins and intrahepatic inferior vena cava, precluding safe venous access, which is also a relative contraindication for performing transjugular liver biopsy[14]. Consequently, a percutaneous route was chosen after multidisciplinary discussion with interventional radiologist which ultimately yielded sufficient diagnostic material. This highlights that while transjugular liver biopsy is the procedure of choice in high-risk patients, percutaneous biopsy remains a valid alternative when transjugular access is not feasible.

Although MRI may provide additional diagnostic clues in cases of diffuse hepatic infiltration, in our patient, this modality was not feasible due to rapid clinical deterioration, impaired consciousness, and limited technical availability. After consultation with radiology colleagues, and considering the urgent need for histological confirmation to guide further management, the team decided to proceed directly with liver biopsy. This approach ensured timely diagnosis in a setting where delaying the procedure for further imaging was deemed unsafe.

Our patient received aggressive supportive therapy, including ICU care, mechanical ventilation, dialysis, and vasoa

This case highlights the rare but devastating presentation of ALF caused by diffuse hepatic infiltration of metastatic melanoma. The clinical onset was non-specific and initially mimicked vascular hepatic emergencies such as Budd-Chiari syndrome, illustrating the diagnostic challenge in distinguishing infiltrative malignancy from other acute hepatologic conditions. The absence of a known malignancy, along with misleading imaging and rapid clinical deterioration can often delay the correct recognition. Diagnosis was ultimately confirmed by liver biopsy, underscoring its critical role in unexplained ALF. Despite aggressive supportive management and initial consideration for liver transplantation, the discovery of metastatic melanoma rendered the patient ineligible. It reinforces the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for occult cancer in ALF, even in patients without documented oncologic history, and emphasizes the need for rapid diagnostic pathways to guide appropriate therapeutic decisions.

| 1. | Maiwall R, Kulkarni AV, Arab JP, Piano S. Acute liver failure. Lancet. 2024;404:789-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 40.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ichai P, Samuel D. Etiology and prognosis of fulminant hepatitis in adults. Liver Transpl. 2008;14 Suppl 2:S67-S79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | O'Neill RS, Leaver P, Ryan C, Liang S, Sanagapalli S, Cosman R. Metastatic melanoma: an unexpected cause of acute liver failure. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2024;17:1125-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee Y, Lee J, Kim H, Park C, Jung J, Kim D, Chung YJ, Ryu H. Acute Liver Failure Secondary to Hepatic Infiltration of Malignant Melanoma. Clin Endosc. 2022;55:287-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Escobar-Valdivia E, Monreal-Robles R, Delgado-García G, Hernández-Velazquez B. Fulminant hepatic failure due to metastatic choroidal melanoma. Caspian J Intern Med. 2017;8:59-62. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Te HS, Schiano TD, Kahaleh M, Lissoos TW, Baker AL, Hart J, Conjeevaram HS. Fulminant hepatic failure secondary to malignant melanoma: case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:262-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schlevogt B, Rehkämper J, Hild B, Schmidt HH. Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic: Fulminant liver failure from diffuse leukemoid hepatic infiltration of melanoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:1795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Montero JL, Muntané J, de las Heras S, Ortega R, Fraga E, De la Mata M. Acute liver failure caused by diffuse hepatic melanoma infiltration. J Hepatol. 2002;37:540-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bouloux PM, Scott RJ, Goligher JE, Kindell C. Fulminant hepatic failure secondary to diffuse liver infiltration by melanoma. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:302-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bellolio E, Schafer F, Becker R, Villaseca MA. Fulminant hepatic failure secondary to diffuse melanoma infiltration in a patient with a breast cancer history. J Postgrad Med. 2013;59:164-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tanaka K, Tomita H, Hisamatsu K, Hatano Y, Yoshida K, Hara A. Acute Liver Failure Associated with Diffuse Hepatic Infiltration of Malignant Melanoma of Unknown Primary Origin. Intern Med. 2015;54:1361-1364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mashayekhi S, Gharaie S, Hajhosseiny R, Patel K. A rare presentation of malignant melanoma with acute hepatic and consecutive multisystem organ failure. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e330-e331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tanaka M, Watanabe S, Masaki T, Kurokohchi K, Kinekawa F, Inoue H, Uchida N, Kuriyama S. Fulminant hepatic failure caused by malignant melanoma of unknown primary origin. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:804-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bettinger D, Berzigotti A, Mandorfer M, Ripoll C, Labenz C, Zizer E, Bruns T, De Gottardi A, Emrich J, Engelmann C, Maasoumy B, Ferlitsch A, Fuhrmann V, Hinrichs J, Jansen C, Lackner K, Matzberger R, Meyer C, Mozayani B, Praktiknjo M, Reuken PA, Schultheiss M, Zipprich A, Lange CM, Kloeckner R, Sarrazin C, Trebicka J, Reiberger T, Bosch J, Dollinger MM; German (D)–Austrian (A)–Swiss (CH) portal hypertension (DACH-PH) consortium. Transjugular diagnostic procedures in hepatology: Indications, techniques and interpretation. JHEP Rep. 2025;7:101437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/