INTRODUCTION

Chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T)-cell therapy engineers autologous T cells to acquire specific tumor antigen recognition and cytotoxicity through genetic modification. Since the approval of the first anti-CD19 CAR-T product, this approach has achieved long-term remission and curative outcomes in relapsed/refractory hematological malignancies such as B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, reshaping the therapeutic landscape for these diseases[1]. However, CAR-T therapy faces persistent challenges in solid tumors. The tumor microenvironment (TME) exhibits potent immunosuppressive properties, characterized by infiltration of inhibitory cells, including cancer-associated fibroblasts, regulatory T cells (Treg), tumor-associated macrophages, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and secretion of inhibitory cytokines such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and interleukin (IL)-10. Chronic antigen stimulation and metabolic stress within the TME further drive CAR-T cells into an exhausted state, marked by impaired proliferation, reduced effector function, and elevated expression of inhibitory receptors [e.g., programmed death-1 (PD-1), T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3]. Consequently, CAR-T cells exhibit insufficient in vivo persistence, leading to response rates and remission durations for solid tumors that are markedly inferior to those achieved in hematological malignancies[2,3].

To address these limitations, strategies such as immune checkpoint blockade, TME remodeling, and cytokine modulation have been explored. Among these, the common gamma chain (γc) cytokine family, encompassing IL-2, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, and IL-21, has emerged as a pivotal tool for enhancing CAR-T cell function due to its central role in regulating T cell immune responses. As a shared receptor subunit for these cytokines, γc (CD132) serves as an essential hub for signal transduction: All γc family members require binding to Janus kinase 3 (JAK3) via γc to activate downstream JAK-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathways, thereby precisely regulating T cell proliferation kinetics, differentiation fate, and survival[4]. γc cytokines efficiently support in vitro CAR-T cell expansion, promote differentiation into stem cell-like memory T cells (Tscm) or central memory T cells (Tcm), significantly prolong in vivo persistence, and enhance resistance to exhaustion. This positions γc cytokines as critical for overcoming core limitations of CAR-T therapy in solid tumors.

Focusing on γc cytokine-driven CAR-T optimization, this review synthesizes current research and key advances. First, it integrates recent findings to elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which specific γc cytokines (e.g., IL-7, IL-15, IL-21) regulate CAR-T cell proliferation, survival, differentiation, and TME adaptability, highlighting functional distinctions and synergies to establish a theoretical framework linking “signaling pathway activation-functional remodeling-therapeutic enhancement”. Second, it summarizes key technical strategies for CAR-T optimization using γc cytokines, including concentration gradient modulation in vitro culture (e.g., low-dose IL-2 combined with IL-7/IL-15), endogenous cytokine co-expression in CAR-T cells (e.g., membrane-anchored IL-15/IL-21), and γc receptor chimerization (e.g., IL-4Rα-IL-21R intracellular domain recombination). It further analyzes application contexts and limitations of each strategy (e.g., systemic toxicity of exogenous cytokines, complexity of genetic modifications). Third, it examines clinical evidence, such as IL-15-enhanced glypican-3 (GPC3) CAR-T and IL-7/C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL) 19-modified 7 × 19 CAR-T. Through this integrated “mechanism-technology-clinical practice” analysis, this review provides theoretical insights and practical guidance for translating γc cytokine-enhanced CAR-T therapy, facilitating its evolution from a “curative modality for hematological tumors” to a “controllable approach for solid tumors”, thereby offering new therapeutic options for patients with relapsed/refractory solid malignancies.

DISSECTION OF THE ΓC CYTOKINE FAMILY

γc (CD132) was initially characterized as the third subunit of the high-affinity IL-2 receptor complex and serves as an indispensable component for receptors of multiple cytokines, including IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, and IL-21, collectively termed γc family cytokines. These cytokines play essential roles in immune regulation: Their distinct structural features, cellular sources, receptor assemblies, and signaling cascades collaboratively sustain immune homeostasis while exerting precise control over T cell development, proliferation, differentiation, and survival.

IL-2, the first cloned γc family member, is encoded on chromosome 4. Its mature protein (approximately 15.5 kDa) adopts a classic four-α-helix bundle structure[5,6]. Immune responses feature strict activation-dependent IL-2 secretion: Primarily produced by antigen-stimulated CD4+ helper T (Th) and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, it requires synergistic T cell receptor and co-stimulatory (e.g., CD28/B7) activation for robust release. Consequently, IL-2 functions as the core signaling molecule mediating T cell clonal expansion and effector function initiation.

IL-4, encoded at 5q31.1[7], resides within a critical immune gene cluster containing IL-3, IL-5, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor loci, enabling coordinated regulation of immune response bias. Its secretion demonstrates marked cellular specificity: Primarily sourced from Th2 cells (which drive humoral immunity), with basophils, mast cells, and type 2 innate lymphoid cells contributing minimally upon allergen/inflammatory stimulation. Functionally, IL-4 drives B cell class switching (e.g., to IgE-secreting cells) and Th2-type immune polarization.

IL-7, essential for lymphocyte development, maps to 8q21.13. Polymorphisms here associate with immunodeficiency susceptibility [e.g., severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), allergic diseases] and osteoarthritis (rs2583759 locus)[8]. Physiologically, bone marrow/thymic stromal cells and intestinal lamina propria cells secrete IL-7, creating microenvironments critical for lymphopoiesis: Thymic T cell differentiation (double-negative to double-positive stages) and bone marrow B cell precursor proliferation. Complete γc deficiency, blocking IL-7 signaling, causes X-linked SCID, characterized by near-absent T/B cells and neonatal fatal infection risk[9].

IL-9, another γc family member, localizes to 5q31.1. Its secretion spans multiple lineages: Principally Th9 cells (IL-4/TGF-β-differentiated CD4+ T subset), with type 2 innate lymphoid cells, Th17 cells, activated mast cells, and memory B cells contributing during inflammation[10]. Core functions encompass mucosal defense enhancement, allergic inflammation mediation, and effector T cell (Teff) infiltration/activation in anti-tumor immunity.

IL-15 maps to 4q31.21[11,12]. Despite amino acid homology (approximately 15%) and structural similarity with IL-2, its sources and functions diverge significantly: Primarily produced by innate immune cells (dendritic cells/monocytes/macrophages) and non-immune cells (epithelial cells/fibroblasts), independent of T cell activation. IL-15 secretion occurs via membrane-anchored or extracellular matrix-retained “IL-15/IL-15Rα complexes”, signaling through trans-presentation (IL-15Rα presents IL-15 to adjacent IL-2Rβ/γc-expressing cells). This mechanism prioritizes memory T cell survival and natural killer (NK) cell activation over T cell clonal expansion.

IL-21 co-localizes with IL-2 at chromosome 4. Genetic variations here link to autoimmune disease risks (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis)[13,14]. Structurally, mature IL-21 contains a typical four-α-helix bundle and a unique 19-amino-acid N-terminal signal peptide enabling efficient processing/secretion. Cellularly, activated CD4+ T subsets (follicular Ths/Th17) and NK cells serve as primary sources. Functionally, it regulates humoral immunity while enhancing NK/CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity, and contributes to mucosal inflammation (gut/respiratory tract) and autoimmune pathogenesis.

THE ΓC-JAK-STAT SIGNALING PATHWAY: A REGULATORY HUB FOR IMMUNE CELL DEVELOPMENT, SURVIVAL, AND FUNCTIONAL DIFFERENTIATION

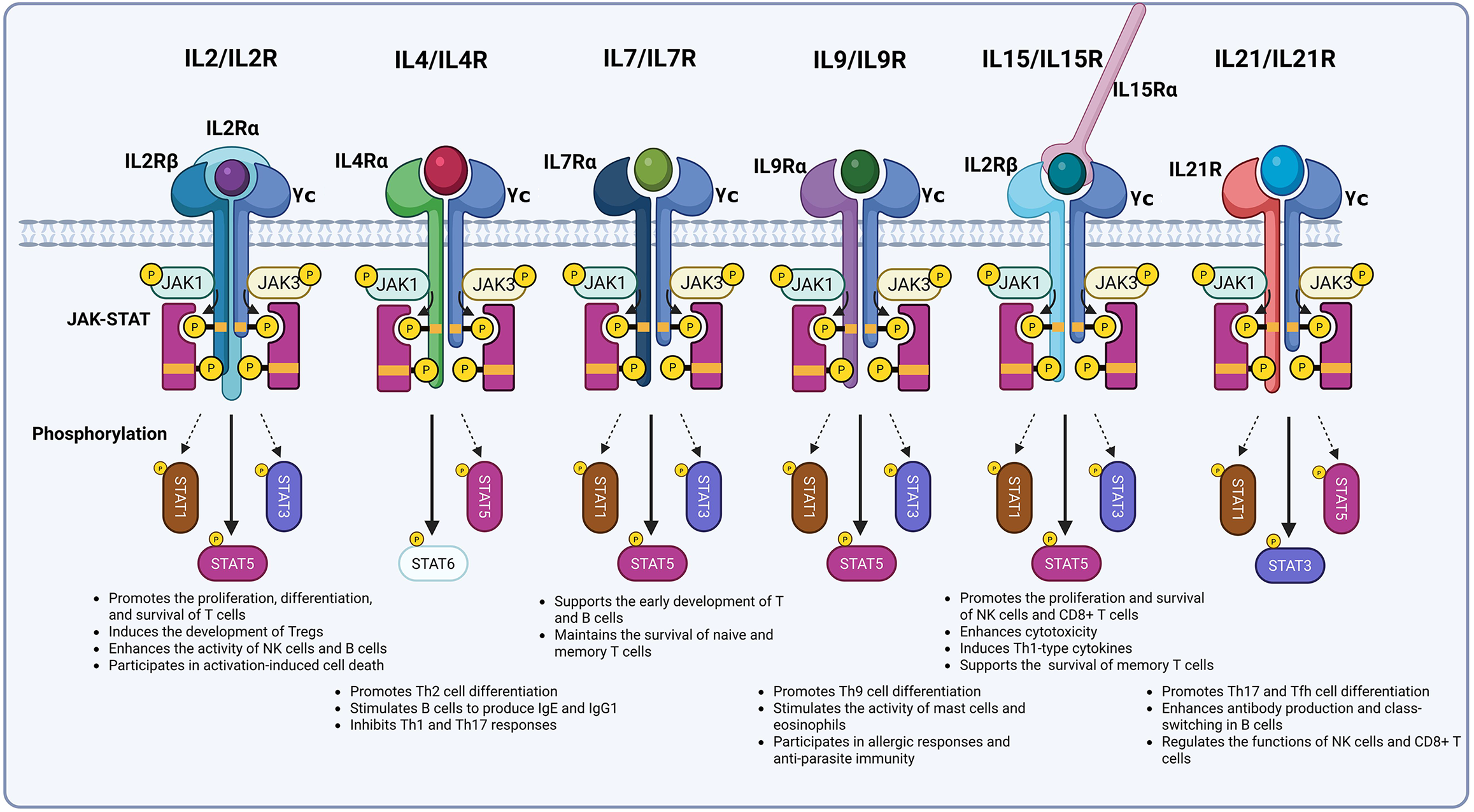

Members of the γc cytokine family exhibit distinct functions, yet all rely on the γc-mediated JAK-STAT signaling pathway to exert their core regulatory effects. In this process, γc functions as a “signal initiation hub”: Through specific binding to JAK3, it triggers a kinase cascade that ultimately regulates immune cell development, proliferation, differentiation, and survival. Consequently, γc serves as the “signaling center” essential for maintaining normal immune system operation (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Dissection of the gamma chain cytokine family.

IL: Interleukin; γc: Gamma chain; JAK: Janus kinase; STAT: Signal transducer and activator of transcription; NK: Natural killer; Th: T helper cell.

Receptor assembly function: An essential unit ensuring high-affinity binding and signal initiation

As a shared receptor subunit for γc family cytokine receptors, γc’s core function is primarily manifested in its capacity to ensure high-affinity binding and signal transduction capabilities within receptor complexes. It acts as an indispensable structural component, enabling receptors to transition from “ligand-specific subunit binding” to a “functional complex”, and constitutes the “essential structural unit” required for all family members to fulfill their physiological functions.

The IL-2 and IL-15 receptors exemplify heterotrimeric structures. The IL-2 receptor comprises the low-affinity subunit IL-2Rα (CD25; Kd approximately is 10-8 M), the intermediate-affinity subunit IL-2Rβ (CD122), and γc. While IL-2Rα mediates initial IL-2 binding without independent signaling capacity, the IL-2Rβ/γc dimer exhibits intermediate affinity (Kd approximately is 10-9 M) but limited signal transduction efficiency. Only the IL-2Rα/β/γc trimer forms a high-affinity receptor (Kd approximately is 10-11 M), ensuring IL-2 initiates signaling at minimal concentrations and representing the primary mechanism for its physiological functions[15-18]. The IL-15R consists of the high-affinity specific subunit IL-15Rα (Kd approximately is 10-11 M), the shared subunit IL-2Rβ (CD122), and γc. Here, IL-15Rα functions as a “presenting molecule”, trans-presenting IL-15 to target cells expressing IL-2Rβ/γc with minimal direct signaling involvement, thereby defining IL-15’s primary mode of action[19]. Within this complex, γc and IL-2Rβ enable “signal sharing”: IL-15 and IL-2 transmit partially overlapping signals (e.g., T cell proliferation) through shared β/γc subunits. However, distinct α subunits confer immune functional specificity, IL-15 maintains memory T cells, while IL-2 activates Teffs.

Receptors for IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, and IL-21 adopt heterodimeric configurations. The lymphocyte-specific type I IL-4 receptor contains IL-4Rα (CD124) and γc; the IL-7R combines IL-7Rα (CD127) with γc; the IL-9R includes IL-9Rα (CD129) and γc; and the IL-21R pairs IL-21R (CD360) with γc. During assembly, cytokines initially bind specific subunits (e.g., IL-4/IL-4Rα), forming “single-subunit complexes” that subsequently engage γc. Interactions between γc and specific subunits (e.g., IL-7Rα) convert these binary complexes into active ternary complexes (e.g., IL-4/IL-4Rα/γc)[20-23]. Crucially, γc incorporation drives the transition from “single-subunit complexes” to “signal-transduction-competent states”. As an “essential structural bridge”, γc mediates ligand-specific subunit binding to shared (e.g., IL-2Rβ) or specific subunits, finalizing receptor assembly. Through conformational modulation and affinity enhancement, γc transforms receptors from “inactive binding states” to “signal-transduction-competent active states”, establishing its indispensability. Without γc, ligand binding (e.g., IL-4) achieves recognition but fails to form functional receptors or mediate lymphocyte regulation.

Signal initiation: Specific binding of γc to JAK3 triggers the signal cascade

The intracellular domain of γc harbors highly conserved Box1 and Box2 motifs. Box1, a proline-rich sequence, binds specifically to the FERM domain of JAK3. Box2, positioned downstream of Box1, maintains γc’s intracellular conformation and stabilizes the JAK3/γc complex via SH2 domain interactions, priming it for signal activation[24-26]. Cytokine binding (e.g., IL-2 to IL-2Rα/β/γc) induces conformational changes in receptor subunits, juxtaposing γc-bound JAK3 with JAK1 (bound to receptors like IL-2Rβ or IL-4Rα) to trigger cross-phosphorylation. Activated JAK kinases phosphorylate tyrosine residues in receptor subunits (e.g., IL-2Rβ Tyr338/Tyr392; IL-7Rα Tyr449), creating SH2-domain-dependent STAT docking sites[27,28]. IL-2-bound phosphorylated IL-2Rβ recruits STAT5A/5B; IL-4-activated IL-4Rα recruits STAT6; and IL-21-stimulated IL-21R recruits STAT3. Although γc does not directly recruit STATs, γc-mediated JAK3 activation is prerequisite for STAT phosphorylation. Deficiencies in γc or JAK3 mutations (e.g., X-linked SCID-associated) universally block γc cytokine-induced STAT activation, causing global immune signal disruption[4].

Signal differentiation: Differential regulation by γc family cytokines drives selective activation of JAK-STAT signals

While all γc family cytokines activate JAK1/JAK3 via γc, they exhibit distinct STAT activation profiles: IL-2, IL-7, IL-9, and IL-15 primarily activate STAT5; IL-4 predominantly activates STAT6; and IL-21 mainly activates STAT3. This “signal differentiation” stems from synergistic γc-specific subunit interactions. First, specific subunit intracellular domain sequences dictate STAT binding preferences. For example, IL-2 induces JAK-mediated phosphorylation of IL-2Rβ Y392/Y510 to generate STAT5 sites, whereas IL-4 triggers phosphorylation of IL-4Rα Y575/Y603/Y631 for STAT6 recruitment[29-31]. Second, γc modulates JAK kinase activation intensity, influencing STAT phosphorylation efficiency. Despite both activating STAT5, IL-2 and IL-15 differ critically: IL-2 promotes faster IL-2Rβ/γc internalization, while IL-15 induces lower-magnitude but prolonged STAT5 phosphorylation. These signaling distinctions underlie functional divergence, IL-15 sustains memory T cell survival, whereas IL-2 drives Teff proliferation[32-34].

Functional differentiation: Differential signaling pathways shape the functional diversity of immune cells

γc-transduced JAK-STAT signals critically determine the fate of T cells, NK cells, and NKT cells, with T cell regulation being central. IL-7, via γc-mediated STAT5 activation, provides essential signals for thymic T cell development. Thymic epithelial cell-derived IL-7 binding to thymocyte IL-7R (γc/IL-7Rα) activates STAT5, which regulates RUNX3 and T cell receptor γ expression to drive progression from double-negative to double-positive and single-positive stages. γc deficiency arrests development at the double-negative stage[35-38]. IL-7 and IL-15 sustain peripheral T cell homeostasis through γc-STAT5 signaling: IL-7 upregulates anti-apoptotic proteins [B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2)/Bcl-extra large] and inhibits pro-apoptotic factors to protect naive T cells; IL-15 maintains memory CD8+ T cells via persistent STAT5 activation. γc dysfunction causes peripheral T cell apoptosis due to absent survival signals. Distinct γc cytokines further direct T cell subset differentiation: IL-2/STAT5 promotes Teff (pathogen/tumor clearance) and Treg (immune balance); IL-4/STAT6 induces Th2 cells (humoral immunity); IL-21/STAT3 generates Th17 and follicular helper T cells (inflammation/B cell antibody production). Additionally, γc signals regulate other immune cells: IL-15 and IL-21 activate STAT3 and STAT5 via γc to enhance NK cell development, activation, and cytotoxicity, bolstering anti-tumor and anti-infection immunity.

APPLICATION OF ΓC CYTOKINES IN CAR-T CELLS

CAR-T therapy has achieved significant advancements in treating hematological malignancies. Nevertheless, two primary challenges persist, limiting its efficacy: The conflict between “short-term massive expansion for tumor elimination” and “long-term maintenance of stemness to prevent relapse”, and the functional exhaustion driven by the TME in solid tumors. γc family cytokines, which share the common γc (CD132) to activate signaling pathways such as JAK-STAT and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-protein kinase B (AKT), can selectively modulate CAR-T cell proliferation, stemness, and effector functions, offering critical targets for balancing “expansion-stemness” and improving in vivo activity.

Enhancing stemness potential maintenance and inhibiting excessive differentiation and exhaustion

Maintaining stemness during the in vitro preparation and in vivo activity of CAR-T cells is essential for ensuring long-term persistence, resistance to exhaustion, and sustained anti-tumor efficacy. However, chronic in vitro activation, whether through CAR or co-stimulatory signals, often leads to stemness loss, marked by increased exhaustion markers [PD-1, lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3)], reduced self-renewal capacity, and diminished long-term survival. γc family cytokines counteract this by employing multi-pathway regulatory mechanisms to preserve CAR-T cell stemness.

IL-2, a conventional expansion factor, rapidly amplifies Teff via the JAK3-STAT5 pathway, achieving 103-104-fold proliferation within 2-3 weeks to meet clinical dosing requirements (106-108 cells/kg). However, high-dose IL-2 (≥ 100 IU/mL) induces terminal differentiation through nuclear factor of activated T cells signaling, depleting stemness. In contrast, low-dose IL-2 (10-20 IU/mL) promotes “mild proliferation” while preserving Tcm via STAT5, though it may expand Tregs through forkhead box P3. Experimental comparisons show that cultures with ≤ 5 IU/mL IL-2 maintain high early memory frequencies (88%-89%) but exhibit limited expansion, while higher doses progressively reduce memory subsets (e.g., 61% at 300 IU/mL) and enhance proliferation[39].

IL-4 and IL-9, as Th2-type cytokines, regulate CD4+ T cell polarization: IL-4 drives Th2 polarization via STAT6 while suppressing Th1/interferon (IFN)-γ immunity[40,41]. Combined with TGF-β, IL-4 reprograms cells into IL-9-secreting Th9 cells, which display Tcm phenotypes, low inhibitory receptor expression, robust proliferation, and potent anti-tumor activity in solid tumors[42-44].

IL-7 plays a critical role in sustaining stemness both in vitro and in vivo. It activates STAT5-STAT3 signaling to upregulate stemness genes [IL7Rα, transcription factor 7 (TCF7)] and promotes Tcm/Tscm differentiation. Concurrent PI3K-AKT signaling inactivates Bcl-2-associated death promoter and upregulates Bcl-2/Bcl-extra large, reducing cell attrition[45-47]. Compared to IL-2-cultured CAR-T cells, those exposed to membrane-bound IL-7, IL-7Rα, or soluble IL-7 show higher frequencies of naive T cells and Tcm, superior expansion kinetics, and enhanced tumor suppression in vivo[48-50]. The long-acting IL-7 fusion protein NT-I7 similarly outperforms IL-2: It enhances the proliferation of CD19/CD33/GPC3-targeted CAR-T/invariant NKT cells in vitro, increases CD127 (IL-7Rα) expression in Tscm/Tcm/effector memory T cells (Tem) subsets, enhances IL-7 responsiveness, and reduces PD-1/LAG-3 expression on GPC3 CAR-T cells, thereby reinforcing stemness[51-53].

IL-15 uniquely balances cytotoxic activity with memory maintenance. Although less potent than IL-2 for expansion, IL-15 promotes sustained proliferation with a “memory bias” and synergizes with IL-7. IL-15-cultured CAR-T cells (CAR-T/IL-15) exhibit enhanced stemness: Through STAT5/PI3K-AKT synergy, IL-15 preferentially expands Tscm and Tcm populations. Compared to IL-2 cultures, CAR-T/IL-15 shows upregulated memory transcription factors (lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1, TCF7), downregulated effector genes (EOMES, TBX21, granzyme B, perforin), and reduced IFN-γ production. Phenotypically, CAR-T/IL-15 cells harbor more Tscm cells, exhibit lower apoptosis (reduced caspase-3), diminished exhaustion markers [LAG-3, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), PD-1], and superior metabolic fitness. These traits confer greater proliferative capacity, anti-tumor efficacy, and prolonged survival in preclinical models[54].

IL-21, despite limited short-term expansion, serves as an “anti-exhaustion stabilizer”. By activating STAT3, IL-21 modulates the stemness transcription factor SRY-related HMG-box 4 and upregulates TCF7, lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1, and chemokine receptor (CCR) 7, thereby curbing terminal effector differentiation and promoting Tcm generation. Additionally, it increases co-stimulatory molecules (CD27, CD28) associated with low differentiation states[55-57]. In epidermal growth factor receptor CAR-T studies, IL-21-secreting constructs significantly increased Tcm proportions (CD4+ Tcm: 84% vs 68%; CD8+ Tcm: 56% vs 44%), skewing cells toward cytotoxic memory phenotypes[58]. In vitro, IL-21 synergizes with IL-2/IL-7/IL-15, enhancing T cell expansion and increasing naive T cell frequencies[57,59].

Adaptive regulation of TME metabolic stress: Reprogramming and optimization of energy metabolism

Metabolic dysregulation within the solid tumor TME is a primary cause of CAR-T cell functional failure. Solid tumors, in contrast to normal tissues, predominantly rely on glycolysis via the “Warburg effect”, converting large amounts of glucose into lactate even under normoxic conditions. This results in a metabolically hostile TME, characterized by low glucose, high lactate (up to 40 mmol/L), and an acidic pH (6.3-6.9)[60-63]. These conditions deprive CAR-T cells of essential energy substrates, while lactate accumulation inhibits intracellular enzymes and activates apoptotic pathways (e.g., p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase), leading to proliferation arrest, impaired cytotoxicity, and cell death. γc family cytokines differentially reprogram CAR-T cell metabolism from “glycolysis dependence” to “multi-substrate adaptation”, significantly enhancing tolerance to TME stress.

IL-2, a classical γc cytokine, acts as a “short-term effector metabolic regulator” by rapidly supporting the initial energy demands of CAR-T cells. Through JAK3-STAT5 and PI3K-AKT signaling, IL-2 increases the membrane density of glucose transporter (GLUT) 1 to boost glucose uptake and enhances the activity of glycolytic enzymes (lactate dehydrogenase A, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1). This shift toward a high-glycolysis state rapidly generates ATP and biosynthetic intermediates for clonal expansion and effector molecule production (e.g., perforin and granzyme), as evidenced by elevated extracellular acidification rates. However, IL-2 fails to sustain mitochondrial function effectively, inducing mitochondrial fission, membrane potential instability, and insufficient oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) capacity under glucose-depleted conditions. Additionally, its excessive lactate production (> 2 × higher than IL-21) worsens TME toxicity and apoptosis. Thus, IL-2 serves primarily as a “rapid energy switch” during in vitro expansion, with its limitations in TME adaptation highlighting the need for other γc cytokines.

In contrast to IL-2’s transient effector focus, IL-7 facilitates “dual-state metabolic adaptation”, supporting both quiescence and activation. During quiescence, IL-7 maintains cellular homeostasis through OXPHOS of glucose and fatty acids while reducing basal energy consumption. Upon antigen stimulation, STAT5-mediated AKT signaling rapidly upregulates GLUT1 and hexokinase I/II to enhance glycolytic flux, while simultaneously increasing pS6 [mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)], CD98 (amino acid transport), and glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase 2, and suppressing optic atrophy 1 (mitochondrial fusion) and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 [fatty acid oxidation (FAO)], collectively shifting cells toward an effector metabolism[64-68]. IL-7 also supports CD8+ memory T cell metabolic fitness by regulating memory T cell formation via mTORC1-S6K and promoting mitochondrial biogenesis (mitochondrial transcription factor A/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α upregulation) and FAO via AMP-activated protein kinase a1-UNC-51-like kinase 1-autophagy related gene 7 activation. By downregulating hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and upregulating Bcl-6, IL-7 inhibits glycolysis, enabling efficient OXPHOS in glucose-deprived environments[69].

IL-15, in synergy with IL-7, optimizes mitochondrial function and adaptation to low-glucose conditions, particularly early in the TME. IL-15 enhances glucose uptake through JAK3/STAT3-mediated upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and GLUT4 membrane translocation[70], while activating STAT5-mTORC1 to drive mitochondrial biogenesis and OXPHOS for sustained proliferation[71]. Functionally, IL-15-cultured T cells exhibit superior mitochondrial membrane stability and integrity compared to IL-2-cultured cells, demonstrating significantly reduced membrane potential loss under TME-mimetic stress. This preserves energy supply continuity during moderate glucose depletion, complementing IL-7’s role in long-term adaptation[72].

IL-21 uniquely mitigates TME lactate toxicity while enhancing FAO as an alternative energy source. STAT3 activation downregulates glycolytic enzymes (phosphoglycerate kinase 1, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, lactate dehydrogenase A), reducing glucose flux and lactate production by more than two-fold to prevent intracellular acidification[73,74]. IL-21 also upregulates carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a, a rate-limiting enzyme in FAO, enabling preferential utilization of endogenous fatty acids even with reduced CD36/fatty acid translocase-mediated uptake. Additionally, IL-21 improves mitochondrial quality (elevated mitochondrial DNA/nuclear DNA ratio), spare respiratory capacity, and antioxidant defenses (heme oxygenase-1, glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit/glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit, catalase upregulation), while suppressing reactive oxygen species and upregulating Bcl-2. In melanoma models, these metabolic adaptations significantly enhance CAR-T tumor infiltration and sustained cytotoxicity.

In vivo activity enhancement: Dual regulation of effector enhancement and inhibitory antagonism

To mitigate CAR-T cell exhaustion induced by inhibitory factors such as TGF-β and PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) within the solid tumor TME, γc family cytokines (IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, IL-21) target the blockade of inhibitory signals while optimizing the immune microenvironment. This dual action enhances CAR-T cell cytotoxicity and counteracts TME-induced immunosuppression, ensuring sustained anti-tumor activity through the multidimensional maintenance of CAR-T cell function.

In effector enhancement, γc family cytokines activate the JAK-STAT and PI3K-AKT pathways to amplify CAR-T cell anti-tumor effects across several dimensions. Notably, IL-2 significantly promotes CAR-T cell proliferation and induces the secretion of perforin, granzyme B, and IFN-γ. IL-2 also upregulates FasL expression on the cell surface, enabling CAR-T cells to eliminate tumor cells through dual cytotoxic mechanisms: The perforin-granzyme and Fas-FasL pathways[39].

Beyond IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21 offer notable advantages in enhancing CAR-T cell activity. In chordoma-targeted studies, CAR-T cells engineered for autonomous IL-7 secretion show increased secretion of IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, along with significantly improved anti-tumor efficacy[75]. CAR-T cells co-stimulated with IL-7 and IL-15 exhibit a higher proportion of memory T cells and substantially enhanced secretion of IFN-γ and TNF-α, resulting in superior anti-tumor performance in vivo[76,77]. Additionally, supplementing IL-21 24 hours after T-cell activation amplifies IFN-γ secretion by CAR-T cells, further enhancing their tumor-specific cytotoxicity.

Regarding inhibitory antagonism, IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21, as key regulators of T cell survival and differentiation, inhibit TGF-β signaling via a dual mechanism mediated by the JAK-STAT pathway: First, they significantly reduce TGF-β type II receptor expression on CAR-T cells, limiting their binding and responsiveness to TGF-β in the TME; second, they upregulate Smad7 expression, a core negative regulator of TGF-β signaling, which blocks TGF-β-mediated Smad2/3 phosphorylation and downstream signaling[78,79]. Additional studies reveal that IL-15 eliminates MDSCs and suppresses their secretion of immunosuppressive molecules, including IL-10, arginase 1, and TGF-β, further diminishing TME-mediated suppression[80].

ΓC CYTOKINE-DRIVEN OPTIMIZATION STRATEGIES FOR CAR-T CELLS

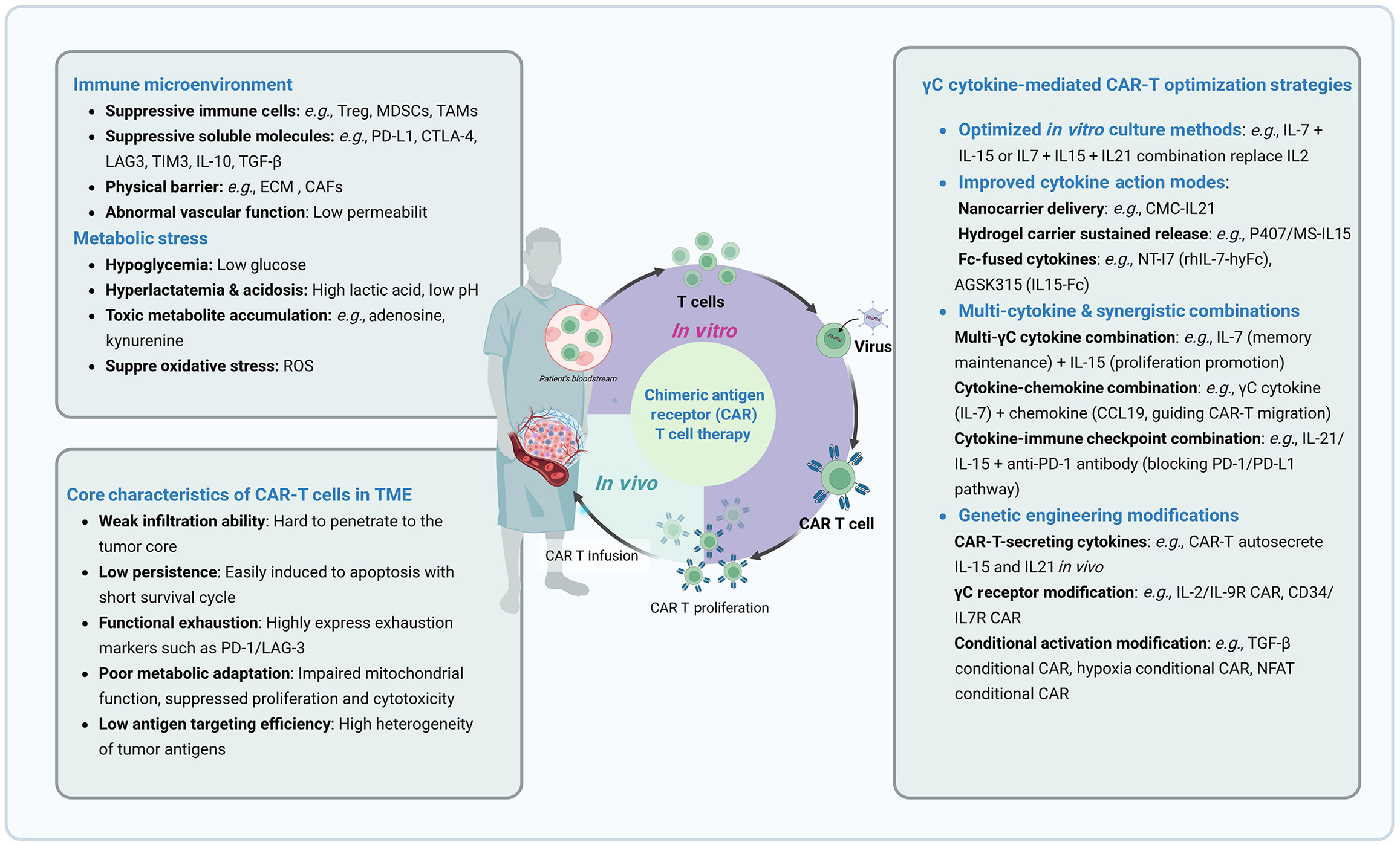

Given their multi-dimensional regulatory roles in CAR-T cell proliferation, stemness maintenance, metabolic adaptation, and anti-suppressive function, γc cytokines have become crucial tools for addressing key challenges in CAR-T therapy, such as “insufficient in vitro expansion efficiency, short in vivo persistence, and poor tolerance to the solid tumor TME”. In alignment with clinical goals of “efficient tumor reduction, long-term tumor control, and low-toxicity safety”, four core optimization strategies have been developed: Precise cytokine selection and matching, spatiotemporal regulation and delivery, synergistic combination of multiple factors, and genetic engineering modification (Figure 2). These strategies provide comprehensive technical support throughout the entire CAR-T cell process, from in vitro preparation to in vivo functional execution, laying the groundwork for enhanced efficacy in treating hematological malignancies and opening new pathways for breakthroughs in solid tumor therapies.

Figure 2 Gamma chain cytokine-mediated chimeric antigen receptor T optimization strategies.

MDSC: Myeloid-derived suppressor cell; TAM: Tumor-associated macrophage; PD-L1: Programmed death-ligand 1; CTLA-4: Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; LAG3: Lymphocyte activation gene 3; IL: Interleukin; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor-β; ECM: Extracellular matrix; CAF: Cancer-associated fibroblast; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; γc: Gamma chain; CAR-T: Chimeric antigen receptor T; PD-1: Programmed death-1; TME: Tumor microenvironment.

Precise cytokine selection and matching: Aligning γc cytokines with tumor type and therapeutic goals

In γc cytokine-driven CAR-T optimization systems, precise cytokine selection is the foundational step to align “cytokine functionality with therapeutic objectives”. γc family members (IL-2, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, IL-21) exhibit distinct heterogeneity in their signaling activation patterns and T cell phenotypic regulation. Their application requires an integrated consideration of the TME architecture, clinical goals (rapid tumor reduction vs sustained tumor control), and potential risks (cell exhaustion, hyperactivation toxicity).

For hematological malignancies (e.g., leukemia, lymphoma), the TME lacks the solid-tissue barriers found in solid tumors and has low infiltration of immunosuppressive cells (e.g., Tregs, MDSCs), allowing CAR-T cells to penetrate the microenvironment and directly target tumor cells. Consequently, γc cytokine selection for these malignancies focuses on “balancing rapid in vitro expansion efficiency with long-term memory cell preservation in vivo”. High-dose IL-2 (in vitro concentration: 50-100 IU/mL) is recommended for urgent, high-tumor-burden scenarios like relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia and acute myeloid leukemia. Short-term combinatorial use during CAR-T preparation stimulates Teff proliferation via JAK3-STAT5 activation, achieving the required clinical infusion of 106-108 cells/kg, while minimizing terminal differentiation risks through strict duration control.

In contrast, solid tumor TMEs present dual challenges: “enhanced metabolic adaptability” and “maintenance of anti-exhaustion phenotypes” due to low-glucose/high-lactate conditions and profound immunosuppression. Therefore, γc cytokine selection must mitigate risks of “terminal differentiation” and “metabolic dysregulation”. While IL-2 drives rapid CAR-T proliferation, it predisposes cells to terminal differentiation, upregulates exhaustion markers (e.g., PD-1), and promotes hyperactivation of aerobic glycolysis, leading to lactic acid accumulation, functional exhaustion, and reduced in vivo persistence. In comparison, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, and IL-21 offer therapeutic advantages through metabolic reprogramming: They sustain mitochondrial integrity, suppress excessive glycolysis, and enhance mitochondrial OXPHOS, improving tolerance to low-glucose/high-lactate environments. These cytokines also increase the proportion of Tscm and Tcm while downregulating exhaustion molecules, providing critical support for enhancing CAR-T efficacy in solid tumors[73,81].

Spatiotemporal regulation and delivery: Dynamically adapting to the lifecycle needs of CAR-T cells

Given the significant temporal dependency and spatial specificity of γc cytokines’ regulatory effects on CAR-T cells following precise selection, implementing spatiotemporal delivery strategies is essential to dynamically support the entire CAR-T cell lifecycle. This approach prevents functional imbalances caused by singular regulatory modes (e.g., hyperproliferation toxicity or inadequate memory persistence), ensuring stage-specific adaptation and precision efficacy enhancement.

The in vitro culture phase is critical in shaping CAR-T cell functional phenotypes, necessitating strict adherence to stage-specific precision regulation principles that balance cell expansion with memory phenotype preservation. As the first clinically applied γc cytokine for T cell expansion, limitations of IL-2 are apparent in its potent induction of Teff terminal differentiation, elevated PD-1 expression, shortened in vivo persistence, and compromised sustained anti-tumor efficacy. In contrast, combining IL-7 and IL-15 offers dual benefits in efficient expansion and memory phenotype preservation during CAR-T manufacturing. Although individually weak (showing only 1/5-1/3 of IL-2’s proliferative capacity), their synergistic use optimizes cellular phenotypes. Compared to 100 IU/mL IL-2 monotherapy, 10 ng/mL IL-7 and 5 ng/mL IL-15 increase CD45RA+CCR7+ memory cells (including Tscm/naive T cells) from 14% to 31%, while preserving robust expansion after 3-5 stimulation cycles[78,82]. Further enhancement is achievable by supplementing IL-7/IL-15 systems with 20 ng/mL IL-21 or by using IL-15/IL-21 combinations, which improve total expansion efficiency by 20%-30% and increase naive T cells proportions to 53%-78%. Additionally, administering IL-21 24 hours post-T-cell activation enhances IFN-γ secretion, thereby augmenting tumor-specific cytotoxicity. In human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-targeted CAR-T cells, IL-21 supplementation increases viral transduction efficiency from 15%-30% to 25%-40%, with transduced cells showing elevated granzyme B and IFN-γ secretion, as well as enhanced cytotoxic activity[59].

Post-infusion, the primary challenge shifts from phenotype shaping to microenvironment adaptation and effector sustenance. Traditional systemic administration creates a bottleneck due to high systemic toxicity risks and insufficient tumor-localized cytokine concentrations, impairing CAR-T cell infiltration, survival, and function. Therefore, local precision delivery technologies that enable spatiotemporal cytokine release are essential. Hydrogel-based systems facilitate sustained release in the TME. In H22 tumor models, the poloxamer 407/Mycobacterium smegmatis-IL15 hydrogel achieves a 4-day in vitro release of IL-15 while reducing systemic toxicity in vivo. This system increases tumor-infiltrating Tem from 63.52% to 74.77%, extends survival, and suppresses malignant ascites formation[83]. Alternatively, nanocarrier systems enhance cellular vitality. In GPC3+ liver cancer models, calcium manganese carbonate-IL21 nanoparticles act as molecular vitality backpacks, reducing PD-1/CTLA-4 expression, increasing Tcm proportions, and upregulating memory markers (CCR7, CD27) and proliferation markers (CD25, Ki67), while boosting IFN-γ/granzyme B secretion, thereby enhancing migration and cytotoxicity without significant toxicity[56].

Beyond spatial delivery, molecular engineering of γc cytokines extends their pharmacokinetics to broaden temporal regulation windows, addressing the short half-lives and frequent dosing requirements of traditional cytokines. Fragment crystallizable (Fc)-fusion proteins (e.g., IL-7/IL-15 fused to IgG1/IgG4 Fc domains) enable neonatal Fc receptor-mediated recycling, reducing renal clearance and proteolysis while enhancing receptor affinity through dimerization[84]. The IL-7-Fc fusion protein NT-I7 extends the half-life from native IL-7’s 6.4-9.8 hours to 52.7 hours, maintaining detectable concentrations for over 7 days post-injection. Subcutaneous administration (60 μg/kg) increases T-cell counts through day 56 and enhances proliferation, anti-tumor activity, and memory phenotype retention in CD19/CD33/GPC3-targeted CAR-T/CAR-invariant NKT cells while reducing relapse risk in liver cancer, acute myeloid leukemia, and lymphoma models[85]. Similarly, the IL-15-Fc fusion ASKG315 extends the half-life from hours to 8-12 days; in melanoma models, 1 mg/kg combined with PD-1 inhibition elevates tumor suppression from 16.3% (monotherapy) to 73.6%[86].

Synergistic combination of multiple factors: Constructing a “1 + 1 > 2” functional complementary network

The complexity of the solid tumor immune microenvironment and the multi-dimensional nature of immune regulation necessitate a multi-faceted approach, as a single γc cytokine cannot adequately meet the comprehensive functional demands of CAR-T cells, including proliferation, stemness maintenance, anti-exhaustion capability, and microenvironment adaptation. Consequently, in addition to precise cytokine selection and spatiotemporal regulation, constructing a complementary functional network through the synergistic combination of multiple factors (or drugs) can overcome the limitations of singular regulation. This approach addresses both the “optimization of cell-autonomous functions” and the “relief of microenvironmental suppression”, achieving “1 + 1 > 2” synergistic efficacy. It provides a flexible adaptation pathway for CAR-T therapy across diverse tumor types.

Combination of γc family cytokines - focusing on enhancing core functions of CAR-T cells: Leveraging their inherent functional heterogeneity, γc family cytokines offer targeted combinatorial advantages that form a core strategy for enhancing CAR-T cells’ fundamental capabilities. Among these, the IL-7/IL-15 combination is widely utilized during CAR-T cell in vitro culture, as it markedly enhances CAR-T cell persistence and effector function, even after repeated antigenic stimulation with tumor cells[87]. Additionally, the IL-15/IL-21 combination demonstrates exceptional advantages in CAR-T cell modification and solid tumor therapy. Integrating both cytokines into vectors [e.g., GPC2-CAR, disialoganglioside (GD2)-CAR, GPC3-CAR] via membrane-anchored forms (such as CD80 linkage) not only mitigates the risks associated with systemic cytokine administration but also preserves CAR-T memory phenotypes by elevating Tscm/Tcm proportions while reducing the generation of exhausted T cells. In high-burden neuroblastoma (NB), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and pancreatic cancer models, modified cells exhibit significantly enhanced sustained cytotoxicity in vitro and proliferative persistence in vivo compared to unmodified CAR-T cells[88-90]. A study focused on HCC illustrates this advantage: 21.15.GBBz CAR-T cells co-expressing IL-15 and IL-21 enhance expansion through TCF1 upregulation. These cells show higher proportions of Tscm and Tcm, with lower differentiation states and significantly reduced apoptosis rates following HCC cell stimulation. Their expansion capacity and functional persistence surpass CAR-T cells expressing single cytokines (15.GBBz, 21.GBBz) or non-cytokine-expressing GBBz CAR-T cells, demonstrating the strongest anti-tumor activity in xenograft models and significantly prolonging survival in tumor-bearing mice[89].

Combination of γc cytokines and chemokines - achieving the dual goals of “function maintenance and targeted recruitment”: The “γc cytokine-mediated cell function maintenance + chemokine-guided migration” strategy addresses the critical bottleneck of “competent CAR-T cells with insufficient tumor infiltration”. In this model, γc cytokines (e.g., IL-7) sustain CAR-T cell proliferative activity and memory phenotype, while chemokines (or CCR modulators) enhance migration and tumor tissue recruitment, creating a synergistic effect of “function maintenance + targeted recruitment”. This approach has proven effective in enhancing intratumoral infiltration and anti-tumor activity across multiple CAR-T platforms. For instance, pairing IL-7 with chemokines or receptor modulators (e.g., CCL19, CCR2b, C-X-C chemokine receptor 5, CCL21) significantly boosts CAR-T migration in NB, melanoma, pancreatic cancer, and osteosarcoma models, amplifying the activity of IL-7-secreting CAR-T cells[64,91,92]. For example, in 7 × 19 CAR-T cells, IL-7 preserves memory phenotypes and proliferative capacity, while CCL19 promotes tumor homing. Compared to second-generation CAR-T cells, 7 × 19 variants exhibit higher Tscm proportions, more efficient IL-7/CCL19 secretion, accelerated proliferation, reduced immune checkpoint expression (PD-1, CTLA-4), and superior anti-tumor activity in systems targeting Nectin4, CD19, GM2, and B cell maturation antigen[93-97].

Combination of γc cytokines and immune checkpoint inhibitors - dual-dimensional resolution of immunosuppression: Targeting the hallmark of exhausted T cells, high expression of immune checkpoint molecules such as PD-1, the γc cytokine/checkpoint inhibitor combination resolves immunosuppression through dual mechanisms: “Enhancing cell anti-exhaustion” and “relieving microenvironment suppression”. In traditional combinations, γc cytokines (e.g., IL-21) activate STAT3 signaling to reduce exhaustion markers (e.g., PD-1, LAG-3) on CAR-T cells while promoting Tscm/Tcm differentiation, thereby preserving long-term functional potential. Checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., PD-1 antibodies) block the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway to alleviate TME-mediated T cell suppression, enabling γc-optimized T cells to exert cytotoxicity. Fusion protein technology, integrating PD-1 antibodies with γc cytokines (IL-15, IL-21) into a single molecule, advances this approach to “precision-targeted regulation”. By exploiting PD-1 antibody specificity, these fusion molecules deliver cytokines directly to PD-1+ exhausted T cells, minimizing non-specific activation (e.g., inflammatory responses) and enabling “point-to-point” functional restoration. This targeted delivery markedly improves both efficiency and safety. The PD-1Ab21 (PD-1 antibody-IL-21 fusion protein) exemplifies this strategy, executing both “PD-1 blockade” and “IL-21 signal transduction”. It binds to PD-1+ cells to inhibit PD-1/PD-L1 interaction while retaining full IL-21 bioactivity, inducing a 50% differentiation of activated CD8+ T cells into naive-like T cells, significantly outperforming IL-21 alone (approximately 30%), thus laying the groundwork for sustained T cell activity. In CT26 colorectal cancer, MC38 colon cancer, TUBO breast cancer, and B16-OVA melanoma models, PD-1Ab21’s tumor inhibition significantly outperforms anti-PD-1 monotherapy and conventional PD-1/IL-21 combinations[98,99]. Similarly, the anti-mPD1-IL15m fusion demonstrates potent tumor suppression with low toxicity: In B16 melanoma and MC38 models, it inhibits tumor growth without inducing cytokine-related weight loss, surpassing IL-15 superagonists, anti-mPD-1 monotherapy, and their combination. This fusion strategy targets the synergy of γc cytokines and checkpoint inhibitors specifically to exhausted T cells, enhancing dual-dimensional immunosuppression resolution and optimizing immunotherapy precision.

Combination of γc cytokines and chemotherapeutic drugs - creating favorable conditions for “microenvironment optimization and cell efficacy enhancement”: The γc cytokine/chemotherapy combination works through a two-step process: “Microenvironment preconditioning optimization” followed by “CAR-T cell functional enhancement”, resulting in synergistic “1 + 1 > 2” efficacy. Low-dose chemotherapeutics (e.g., cyclophosphamide, fludarabine, gemcitabine) reshape the TME via immunomodulation by selectively depleting immunosuppressive cells (e.g., Tregs, MDSCs, tumor-associated macrophages), reducing inhibitory cytokine secretion (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β), and disrupting immunosuppressive barriers. Simultaneously, chemotherapy induces tumor immunogenic cell death, releasing damage-associated molecular patterns (such as calreticulin, ATP, and high mobility group box 1) that activate dendritic cells, enhance antigen presentation, and provide co-stimulatory signals for CAR-T activation. In this optimized microenvironment, γc cytokines (IL-15, IL-21) enhance CAR-T cell function: IL-15 activates STAT5 and PI3K-AKT pathways to promote CAR-T proliferation and anti-apoptosis, reducing cell loss; IL-21 utilizes STAT3 signaling to drive metabolic reprogramming, improving CAR-T tolerance to chemotherapy-induced hypoglycemia and hypoxia, while increasing granzyme B and perforin secretion for enhanced cytotoxicity. This dual-pronged strategy, “relieving microenvironment barriers + upgrading CAR-T functions”, synergistically enhances anti-tumor efficacy.

Genetic engineering modification: Achieving “endogenous autonomous regulation” of γc signaling

While strategies like precise selection, spatiotemporal regulation, and multi-factor combinations have greatly improved γc cytokine regulatory efficiency, traditional exogenous administration still faces inherent limitations, including challenges with dose control, systemic toxicity, and insufficient tumor-localized concentration. Thus, integrating γc cytokines or their receptors directly into CAR structures via genetic engineering, allowing CAR-T cells to “autonomously secrete cytokines” or “precisely respond to microenvironmental signals”, has emerged as a key strategy to overcome these constraints, achieving true endogenous autonomous γc signaling regulation. Currently, three core modification paradigms have been established.

Cytokine-secreting CAR: Cytokine-secreting CAR-T cells are engineered to co-express immunostimulatory cytokines, primarily γc-dependent family members such as IL-7, IL-15, or IL-21, alongside the chimeric antigen receptor. This strategy establishes an autocrine/paracrine feedback loop: Upon recognition of tumor antigen, the CAR-T cell not only mediates direct cytotoxicity but also locally secretes cytokines that enhance its persistence, Tscm properties, and resistance to exhaustion, while concurrently reshaping the immunosuppressive TME. Notably, IL-15-secreting CAR-T cells sustain a Tscm-like phenotype and recruit NK cells through paracrine signaling; dual secretion of IL-7 and IL-21 augments metabolic adaptability and anti-exhaustion capacity in solid tumors; and CD19-targeted CAR-T cells expressing membrane-bound IL-7 (anchored via CD8 transmembrane domains) demonstrate markedly improved in vitro expansion and prolonged survival[100].

γc receptor-modified CAR (orthogonal CAR): Chimeric receptor redesign enables “signal reprogramming” through cross-family domain recombination for “directional activation”. For example, the IL-2/IL-9R chimeric CAR fuses the extracellular domain of the IL-2 receptor with the intracellular domain of the IL-9 receptor α-chain (IL-9Rα). This modification restricts receptor responsiveness exclusively to engineered “orthogonal oIL-2” (a non-native IL-2 analog), bypassing endogenous IL-2. Upon activation, redirected intracellular signaling triggers the STAT1/STAT3/STAT5 pathway, inducing a dual “Tcm + Teff” phenotype that preserves Tcm longevity while retaining potent cytotoxicity, without affecting native T cells[101,102]. Similarly, the “IL-4 receptor extracellular domain-IL-21 receptor intracellular domain” chimeric strategy converts the TME’s immunosuppressive IL-4 signal (e.g., promoting M2 macrophage polarization) into IL-21-mediated activation. Modified CAR-T cells exhibit upregulated Bcl-6 (a memory-associated transcription factor), suppressed B-lymphocyte-induced maturation protein-1 (an effector function inhibitor), and elevated granzyme B levels, enhancing immediate cytotoxicity while maintaining memory homeostasis[103]. Additionally, substituting the IL-7Rα extracellular region with the CD34 molecule’s ectodomain eliminates the need for exogenous IL-7. This self-activating chimeric receptor, validated in GD2-CAR and AXL-CAR systems, significantly increases CAR-T secretion of IFN-γ and TNF-α while enhancing anti-tumor activity against NB and pancreatic cancer[104-106].

Conditional CAR: Conditional CARs utilize distinctive TME signals, such as elevated TGF-β, hypoxia, or antigen recognition, as “molecular switches” to trigger γc cytokine expression/secretion exclusively within lesions or upon tumor contact. This achieves “spatiotemporally precise regulation”: Ensuring tumor-localized cytokine concentrations for CAR-T functional enhancement while preventing systemic toxicity from continuous release, offering a safer solution for high-burden solid tumors. Targeting TME inhibitory signals, TGF-β-responsive promoters (Smad binding elements) or hypoxia-responsive promoters (hypoxia-responsive elements) drive IL-7/IL-15 expression. When CAR-T cells infiltrate TGF-β-rich microenvironments (e.g., pancreatic/colorectal cancers) or hypoxic niches, these promoters induce cytokine secretion, maintaining the Tscm phenotype, enhancing mitochondrial metabolism, and countering TGF-β immunosuppression for adaptive regulation[107-109]. Alternatively, CAR-recognition-activated nuclear factor of activated T cells signals (e.g., triggered by GD2 in NB) serve as switches for IL-15/IL-21 regulation. Post-antigen engagement, membrane-anchored IL-15/IL-21 expression is induced on CAR-T surfaces. Compared to constitutively anchored designs causing systemic toxicity, this strategy exhibits superior safety[90].

CLINICAL CASE ANALYSIS OF ΓC CYTOKINE-OPTIMIZED CAR-T CELLS

Recent international multi-center clinical studies have validated the safety and efficacy of γc cytokine-optimized CAR-T cells, notably overcoming the historical “no objective response” barrier in solid tumor treatment and providing critical evidence for clinical translation. This section systematically analyzes two pivotal approaches, IL-15-modified solid tumor CAR-T and IL-7/CCL19-modified hematological/solid tumor CAR-T, focusing on clinical trial design, key outcomes, and insights. These cases underscore γc cytokines’ core value in resolving bottlenecks such as short in vivo persistence and poor TME adaptation.

IL-15-enhanced GPC3 CAR-T for solid tumor treatment

GPC3 represents an ideal CAR-T target due to its high expression in solid tumors (e.g., liver, gastric cancers) and minimal expression in normal tissues. However, earlier trials revealed conventional GPC3 CAR-T’s limitations: Weak in vivo expansion, transient persistence, poor TME adaptation, and extremely low objective response rates (ORR). In a landmark November 2025 Nature publication, Steffin et al[110] reported phase I trial results (NCT02905188/NCT32956/NCT05103631/NCT04377932) involving 24 GPC3+ solid tumor patients, establishing IL-15’s clinical value for GPC3 CAR-T therapy. All patients received fludarabine/cyclophosphamide preconditioning before cohort assignment: 12 received conventional GPC3 CAR-T (1 × 107/m2 or 3 × 107/m2), while 12 received IL-15-enhanced 15.GPC3 CAR-T (3 × 107/m2). Results diverged sharply: The conventional cohort showed no objective responses [only 3 (25%) liver cancer patients achieved stable disease (SD)]. Conversely, the 15.GPC3 CAR-T cohort demonstrated significantly improved outcomes: 4 progressive disease, 4 SD, and 4 partial responses. Notably, one SD patient exhibited > 26% tumor reduction, another showed approximately 12.8% reduction (confirmed by reduced positron emission tomography uptake), two alpha-fetoprotein-secreting patients had decreased alpha-fetoprotein levels, and one displayed near-complete liver tumor necrosis. Final disease control rate reached 66.7% with an ORR of 33.3%[110].

Functional and mechanistic studies elucidated 15.GPC3 CAR-T’s superior efficacy. Phenotypically, cells displayed effector-dominant traits: Products showed elevated CD8A/B, ZNF683 (encoding homolog of B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein-1 in T cells), and cytolytic genes (GZM, PRF1), while co-stimulatory receptors (TNFRSF4/9/18) and stemness gene TCF7 were downregulated. Protein-level analysis revealed CD8+ subset enrichment, reduced central memory cells, and increased effector memory/effector populations. Exhaustion marker expression (PD-1+/T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3+) remained comparable to conventional CAR-T, though LAG-3+ cells were slightly elevated. Metabolically, IL-15 co-expression conferred a “low glycolysis-high OXPHOS” phenotype, enhancing tolerance to glucose-deprived TME. Transcriptomic evolution indicated both cohorts underwent NK-like differentiation in peripheral blood (upregulated cytotoxic effector genes, downregulated memory genes), but 15.GPC3 CAR-T exhibited significantly greater expansion, with clear divergence between responders and non-responders.

This study also delivered milestone safety and clinical insights: The 15.GPC3 CAR-T group had a higher cytokine release syndrome (CRS) incidence than the conventional group, but most were grade 1-2 (mainly fever, fatigue). In three CRS cases, the inducible caspase 9 safety switch was activated; following administration of the chemical inducer rimiducid, patients experienced rapid symptom resolution, a marked reduction in circulating 15.CAR-T cells, and normalization of inflammatory cytokine levels (e.g., IL-6, IFN-γ), demonstrating, for the γc cytokine-armored CAR-T trial for solid tumors, the real-world efficacy and reliability of the inducible caspase 9 safety switch. This not only confirms its role as a critical safeguard against uncontrolled immune activation but also establishes a clinically translatable strategy for managing toxicity in high-potency CAR-T therapies. Collectively, this trial marks a breakthrough for γc cytokine optimization in solid tumors: It shattered liver cancer CAR-T’s long-standing “no objective response” barrier with a 33.3% ORR, provided direct clinical validation that IL-15 enhances in vivo CAR-T expansion and persistence, and laid the groundwork for future high-dose, high-activity CAR-T regimens in solid tumors.

IL-7/CCL19-co-modified 7 × 19 CAR-T for solid tumor and hematological malignancy treatment

In solid tumor CAR-T optimization research, the “cytokine-chemokine” co-modification strategy demonstrates significant advantages. 7 × 19 CAR-T represents a novel design employing combined “γc cytokine (IL-7)-chemokine (CCL19)” modification, deriving core benefits from molecular synergy. Structurally, antigen-targeted 7 × 19 CARs [e.g., against GPC3, mesothelin (MSLN), CD19, B-cell maturation antigen] uniformly incorporate a foundational framework of “antigen recognition domain - CD8 transmembrane region - 4-1BB co-stimulatory domain - CD3ζ signaling domain” to ensure tumor recognition and core cytotoxicity. Functional enhancement is achieved through an IL-7/CCL19 co-expression cassette, establishing a triple-functional optimization mechanism of “proliferation-infiltration-memory”.

For solid tumors, preclinical and early clinical studies validate 7 × 19 CAR-T’s synergistic superiority: Compared to conventional second-generation CAR-T, anti-GPC3/MSLN-7 × 19 CAR-T exhibits enhanced tumor targeting and anti-tumor activity in both cell line-derived xenograft and patient-derived xenograft models. Based on these findings, a phase I trial was initiated for GPC3+/MSLN+ advanced HCC, pancreatic cancer, and ovarian cancer patients to evaluate safety and feasibility. Subject gd-g/M-001 (GPC3+ advanced HCC) received computed tomography-guided intratumoral CAR-T injection into three metastatic lesions: The 1.2 cm × 1.3 cm liver tumor demonstrated significant shrinkage by day 10 and complete resolution by day 32, achieving partial response per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours 1.1 without toxicity. Subject gd-g/M-005 (MSLN+ advanced pancreatic cancer with lymph node metastasis) underwent hepatic artery infusion of anti-MSLN-7 × 19 CAR-T (only transient nocturnal fever; no CRS/neurotoxicity), followed by quarterly intravenous boosts. After five infusions, day 240 imaging confirmed complete response with preserved quality of life. Preliminary data from six patients reveal no grade 2-4 adverse events: One pancreatic cancer patient (16.7%) achieved complete response, one HCC patient (16.7%) partial response, and two (33.3%) SD, confirming 7 × 19 CAR-T’s therapeutic potential for GPC3/MSLN-positive advanced solid tumors[111].

In hematological malignancies, 7 × 19 CAR-T demonstrates distinct advantages. A multi-center study developed anti-CD19 7 × 19 CAR-T for relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Preclinical data confirmed superiority over conventional anti-CD19 CAR-T in Tscm/Tcm proportions, anti-apoptotic capacity, IL-7/CCL19 secretion, cytotoxicity against CD19+ tumor cells, and tumor suppression in animal models[90]. The phase I trial (NCT03258047) enrolled 39 relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma patients (dose: 0.5 × 106 kg to 4.0 × 106 cells/kg) with no dose-limiting toxicity: 74.4% experienced CRS (only 12.8% grade 3), while 10.3% developed immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (all grade 3-4, resolved with treatment). The 3-month overall response rate reached 79.5% (56.4% complete response); at 32-month median follow-up, median progression-free survival was 13 months, and median overall survival was not reached (2-year overall survival: 53.8%)[112]. Beyond lymphoma applications, a phase I trial (NCT03778346) for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma reported two patients achieving objective responses within one month of single B-cell maturation antigen-7 × 19 CAR-T infusion: Patient 1 (extramedullary recurrence) attained very good partial response, while patient 2 achieved complete response. No dose-limiting toxicities or grade ≥ 3 serious adverse events occurred[95].

In summary, 7 × 19 CAR-T demonstrates clinically relevant anti-tumor activity across a spectrum of malignancies, spanning solid tumors (HCC, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, ovarian carcinoma) and hematologic neoplasms (relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma and multiple myeloma), despite their divergent immunobiological contexts. This trans-tumor efficacy is underpinned by a rationally designed dual-modality engineering approach: Autocrine/paracrine IL-7 signaling sustains CAR-T cell stemness (Tscm/Tcm phenotype), promotes metabolic fitness, and enhances in vivo persistence through JAK1/3-STAT5 activation, while constitutive CCL19 secretion establishes a chemotactic gradient that recruits CCR7-expressing dendritic cells and naive/Tcm lymphocytes into the TME. This orchestrated remodeling of the immune landscape not only augments intrinsic CAR-T functionality but also fosters adaptive anti-tumor immunity, thereby simultaneously addressing two cardinal limitations in cellular therapy, poor T-cell infiltration in immunologically “cold” solid tumors and inadequate long-term engraftment in systemic hematologic disease. Consequently, the 7 × 19 platform represents a mechanistically grounded and clinically validated strategy for broadening the therapeutic applicability of CAR-T cells beyond conventional indications.

CONCLUSION

Centered on the shared γc receptor subunit, the γc cytokine family (IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, IL-21) establishes a critical regulatory network governing CAR-T cell fate, leveraging its unique molecular architecture, cellular sources, and signaling preferences. Through precise activation of key pathways such as JAK-STAT and PI3K-AKT (e.g., IL-7/IL-15 drive STAT5 to sustain memory phenotypes; IL-21 activates STAT3 to enhance anti-exhaustion capabilities), these cytokines multi-dimensionally reshape CAR-T functions spanning proliferation, differentiation, survival, and metabolic adaptation. This review systematically organizes the mechanistic interplay between γc cytokines and CAR-T cells, delineates the distinct advantages of individual cytokines, and synthesizes four core optimization strategies: Precision cytokine selection, spatiotemporal regulation, multi-factor combination, and genetic modification. Emerging clinical evidence, including IL-15-enhanced GPC3 CAR-T in liver cancer and 7 × 19 CAR-T in lymphoma, validates technical feasibility and establishes foundational frameworks for therapeutic advancement.

Current CAR-T immunotherapy for solid tumors confronts persistent challenges: Potent TME suppression, target antigen escapes due to tumor heterogeneity, and inadequate CAR-T persistence/penetration. While existing γc cytokine optimization strategies demonstrate clear value, enhancing proliferation, memory maintenance, and anti-exhaustion via JAK-STAT pathway modulation, future breakthroughs will hinge on interdisciplinary integration. Key directions include: Developing novel γc cytokine variants (e.g., IL-15 superagonist ALT-803, IL-7-Fc fusion proteins) and targeted delivery systems (degradable hydrogels, tumor-homing nanocarriers) to augment specificity and mitigate systemic toxicity; employing single-cell RNA sequencing and metabolomics to profile TME subtypes, thereby establishing “TME signature-γc cytokine pairing” models while synergizing with immune checkpoint inhibitors and stroma-modulating enzymes; and deploying synthetic biology to engineer “smart CAR-T cells” featuring spatiotemporal control of γc signaling via TGF-β/hypoxia-responsive promoters. As technological innovation and clinical translation accelerate, these advances promise to transform CAR-T therapy from a “curative modality for hematological malignancies” to a “controllable intervention for solid tumors”, ultimately offering new pathways toward long-term survival for patients with relapsed/refractory solid tumors.