INTRODUCTION

Thyroid cancer is the most common malignant tumor of the endocrine system[1]. In recent years, its incidence has been increasing rapidly worldwide, including in China[2,3]. Due to prolonged exposure to a unique occupational environment – characterized by high-altitude hypoxia, ionizing radiation, extreme physiological and psychological stress, and irregular diets and work schedules – military flight personnel face a higher risk of developing thyroid cancer than the general population[4,5]. Thyroid cancer is also the most common malignant tumor among military flight personnel[6]. A diagnosis of malignant tumor renders a pilot unfit for flight duties. Furthermore, severe complications from thyroid cancer treatment, such as hypothyroidism can impair a pilot's concentration and reduce their ability to respond to in-flight emergencies, posing a threat to flight safety; hoarseness and hypocalcemic tetany can lead to permanent grounding, severely impacting the combat readiness of aviation units[7]. With advances in modern medical technology, improvements in clinical treatment outcomes, and enhanced understanding of the biological characteristics and prognosis of thyroid cancer, the likelihood of flight personnel being cleared for flight after treatment has increased. Therefore, understanding the epidemiology of thyroid cancer in military flight personnel and investigating the factors influencing its incidence and prognosis are crucial for its prevention, treatment, medical assessment, and health management. This article systematically reviews the research progress on the epidemiological characteristics, clinical features, management strategies, and preventive measures for thyroid cancer in this population, aiming to provide a reference for standardizing clinical diagnosis and treatment and guiding aeromedical appraisal.

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL FEATURES

Incidence and detection rate

Studies indicate a significantly higher incidence of thyroid cancer among military flight personnel compared to the general population. For example, a large cohort study of 35976 United States military aviators reported a standardized incidence ratio of 0.71 (95%CI: 0.56-0.90) for thyroid cancer[8]. Recent data from thyroid ultrasound screenings of Chinese military flight personnel reveal a thyroid nodule detection rate ranging from 11.55% to 50.4%, which is notably higher than that found in the general population during routine health check-ups. Among these detected nodules, the Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS) categories were predominantly 3 (likely benign) and 4a (low suspicion for malignancy)[6,9]. Notably, the prevalence of thyroid cancer varies significantly by aircraft type. Personnel serving on early warning aircraft exhibit a higher incidence than those on fighters, bombers, transport aircraft, or helicopters. Furthermore, the incidence is significantly higher among combat service personnel compared to those in other combat roles[10]. These disparities are likely attributable to differences in flight altitude, radiation exposure levels, and the intensity of mission-induced physiological and psychological stress across different aircraft types and roles.

Age and gender distribution

In the general population, thyroid cancer predominantly affects women aged 30-50[11,12]. In contrast, among military flight personnel with thyroid cancer, the vast majority (95.8%) are young men, with most cases diagnosed between the ages of 25 and 37[13]. This is likely due to the fact that military flight personnel population is primarily male and the typical age for starting flight duties in this range. Studies have shown that for flight personnel diagnosed with thyroid cancer, the first sign is often the detection of thyroid nodules during routine physical examinations[6,14]. All cases are histologically classified as papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC). Most flight personnel have normal thyroid function at the time of detection. Additionally, as flight time increases, the likelihood of lymph node metastasis in flight personnel with thyroid cancer also rises[14].

Time trend and geographical distribution

With the widespread use of high-definition ultrasound in clinical practice, the average detection rate of thyroid nodules in China has increased from 29.8% to 41.3% in recent years[15]. Concurrently, the incidence of malignant thyroid tumors has risen from 4.9% to 20.1% over the past decade[16]. An analysis of the disease spectrum among Chinese military flight personnel also shows a marked increase in thyroid nodule incidence[17], which has now become one of the top ten most common diseases in this population[18]. This rapid growth trend is partly attributed to the advancements in detection technology and the increased coverage of physical examinations. However, it cannot be fully explained by the increased diagnostic intensity. Radiation exposure is a well-established risk factor for thyroid disease[19]. Flight personnel are occupationally exposed to cosmic radiation. Studies have shown that the annual average effective dose of cosmic radiation for aircrew on polar routes can reach 5.79 ± 0.92 mSv/year, while flight attendants on non-polar routes are exposed to 2.14 ± 0.64 mSv/year[20]. The incidence of thyroid cancer among flight personnel stationed in plateau areas is significantly higher than that in flight personnel based in plain areas, which may be related to the higher intensity of ionizing radiation in plateau regions[21].

DIAGNOSTIC STRATEGIES

The clinical diagnosis of thyroid cancer relies on the comprehensive use of multiple examination methods[22]. High-frequency ultrasound is typically used as the initial screening tool and the primary imaging modality, supplemented by fine-needle aspiration cytology for pathological confirmation. Additionally, serological tests for thyroid function, computed tomography (CT), and radionuclide imaging can be used in conjunction to assess the functional status of the thyroid, the relationship between the tumor and surrounding tissues, and the presence of distant metastasis. These methods together provide a comprehensive foundation for disease staging and the development of treatment plans.

In the current annual medical examinations for aircrew in the Chinese military, thyroid ultrasound has become a routine mandatory screening procedure. Additionally, the TI-RADS, proposed by the American College of Radiology in 2017, is recommended for risk stratification of thyroid nodules[23]. This system primarily scores and classifies nodules based on five key ultrasound characteristics, including nodule composition, echogenicity, shape, margin, and focal hyperechogenicity. Its purpose is to standardize reporting, assess the risk of malignancy, and guide clinical decision-making.

Given the unique occupational demands of military flight personnel, invasive procedures must be approached with extreme caution. Previous guidelines and consensus statements offered relatively broad indications for fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) of thyroid nodules. However, the most recent Chinese Expert Consensus and Operational Guidelines for Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy of Thyroid Nodules and Cervical Lymph Nodes (2025) provides more specific FNAB indications based on the TI-RADS classification[24]. This refinement helps minimize unnecessary invasive examinations and over-treatment in this specific population.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

Surgery

Currently, surgery is the primary treatment for differentiated thyroid carcinoma (DTC)[25]. The surgical management of thyroid cancer in military flight personnel should adhere to the guidelines and consensus principles established by the National Health Commission and relevant professional societies. The specific surgical strategy should be determined through a comprehensive evaluation of factors including tumor size, histologic subtype, extrathyroidal extension, lymph node and distant metastasis, as well as the patient's initial recurrence risk stratification, to ensure an individualized treatment approach.

Ipsilateral thyroid lobectomy plus isthmectomy with ipsilateral central lymph node dissection: Indicated for low-risk PTC with a tumor diameter ≤ 4 cm and no extrathyroidal extension.

Total thyroidectomy with ipsilateral central lymph node dissection: Indicated for patients with a tumor diameter > 4 cm, multifocal disease, lymph node metastasis, or distant metastasis.

Lateral cervical lymph node dissection: For patients with clinically positive lateral cervical lymph nodes (cN1b), lateral cervical lymph node dissection is considered necessary. Among the lateral cervical lymph node regions, the most common metastatic areas are levels III and IV, while the metastasis rates in levels II and V are relatively low[26]. Additionally, levels II and V are located posteriorly and encompass a larger area. Dissecting lymph nodes in these regions not only extends the surgical scope but also increases the risk of complications, thereby potentially reducing the patient's quality of life. Some studies suggest that patients with negative lymph nodes in level IV may avoid dissection of level V lymph nodes[27]. The Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Thyroid Cancer (2022) recommend that the minimum scope of lateral neck dissection should include levels IIa, III, and IV, while the full dissection range includes levels II, III, IV, and Vb. Accurate preoperative assessment of cervical lymph node metastasis is crucial, as it determines the surgical approach and the scope of lymph node dissection, which, in turn, directly impacts the flight personnel's flight eligibility, prognosis, quality of life, and recurrence risk. Studies have shown that the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound combined with CT for detecting cervical lymph node metastasis in thyroid cancer is higher than that of either ultrasound or CT alone[28]. For flight personnel, this combined approach is recommended for preoperative evaluation. If suspicious lymph nodes are identified, ultrasound-guided FNAB should be performed to confirm metastasis, thereby precisely defining the scope of lymph node dissection and minimizing the impact of surgery on flight personnel's return to flight. However, for patients with no clinical evidence of lateral cervical lymph node positivity (cN0), there is still no consensus on whether prophylactic lateral cervical lymph node dissection should be performed[29]. During surgery, great care should be taken to protect the recurrent laryngeal nerve and parathyroid glands to avoid postoperative complications that could impair flight personnel’s flight capability. Postoperatively, adjuvant radioactive iodine (¹³¹I) therapy should be considered based on the final pathology and risk staging, and lifelong thyroid hormone replacement therapy is required[11].

Postoperative thyroid-stimulating hormone suppression therapy

Studies have shown that postoperative thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) suppression therapy in intermediate-risk and high-risk DTC patients can significantly improve survival outcomes[30], whereas its benefits for low-risk DTC patients are limited[31]. However, it is important to note that long-term use of TSH suppression therapy increases the risk of osteoporosis and cardiovascular conditions[32]. For flight personnel, who require sustained concentration under stress, excessive TSH suppression may impair flight endurance, and prolonged use may lead to side effects related to TSH suppression therapy, potentially leading to the termination of their flying career. Currently, there is limited research on the efficacy and target control of postoperative TSH suppression therapy in flight personnel, and further studies are needed.

Thermal ablation

Currently, there is controversy regarding the application of thermal ablation in PTC[33], and high-quality evidence regarding its long-term efficacy is still lacking. As a local therapy, thermal ablation may not achieve complete disease eradication. The 2025 edition of the China Anti-Cancer Association Guidelines clearly states that thermal ablation is not recommended as the initial treatment for PTC. For patients with locally recurrent oligometastatic disease who are intolerant of or refuse surgery, or for lesions with poor response to systemic treatment, thermal ablation may be considered as adjuvant therapy following discussion by a multidisciplinary team to holistic integrative medicine. Thermal ablation is not recommended as the initial treatment for follicular thyroid cancer, medullary thyroid carcinoma, or anaplastic thyroid carcinoma[34].

Prognosis

The prognosis of thyroid cancer is influenced by factors such as histological type, primary tumor size, extrathyroidal extension, vascular invasion, BRAF mutation, and distant metastasis. Patients with DTC generally have a good survival rate, low mortality, and a long survival period, which makes special permission for flight possible for flight personnel with thyroid cancer. However, tumor mortality can vary significantly among different subtypes. The impact of regional lymph node metastasis on prognosis is controversial. Some studies suggest that regional lymph node metastasis does not affect recurrence or survival rates, while other studies indicate that lymph node metastasis is one of the high-risk factors for local recurrence and cancer-related mortality.

Points of focus in aviation medicine

As a special group, flight personnel are exposed to various harmful factors in the flight environment, such as mental stress, high-altitude hypoxia, acceleration, and ionizing radiation from cosmic rays, which increases their risk of developing thyroid cancer. Moreover, thyroid cancer can affect flight personnel’s in-flight performance to varying degrees. In the early stages, when thyroid cancer has no clinical symptoms, its impact on flight is minimal. However, as the tumor progresses, symptoms such as local pain and compression may arise, potentially distracting flight personnel. Postoperative hypothyroidism following thyroid cancer surgery can cause symptoms like memory loss, fatigue, and drowsiness, which affect flight operations. Unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury may cause hoarseness, impairing in-flight communication. Postoperative hypoparathyroidism can lead to hypocalcemia, causing muscle numbness and spasms that directly impact in-flight operations. Postoperative TSH suppression therapy may result in subclinical hyperthyroidism, leading to symptoms including palpitations, hand tremors, heat intolerance, and excessive sweating. It also increases the risk of premature contractions and atrial fibrillation, which may jeopardize flight safety.

MEDICAL ASSESSMENT OF SPECIAL PERMISSION FOR FLIGHT

After receiving standardized treatment, flight personnel with thyroid cancer may initiate the medical assessment for special permission for flight if they meet the following basic criteria and undergo a comprehensive evaluation of aviation medicine concerns (currently, medical assessment for special permission for flight is not allowed for patients with medullary thyroid carcinoma or anaplastic thyroid carcinoma).

Basic criteria

It included: (1) No clinical symptoms or signs post-treatment; (2) No treatment-related complications or sequelae; (3) Stable thyroid function and TSH within target range; (4) Normal dynamic electrocardiogram and submaximal exercise test results; (5) Normal cardiopulmonary exercise function assessment; (6) Normal psychological evaluation; (7) For fighter flight personnel, centrifuge tests meet the requirements of the specific aircraft type; (8) High-performance fighter flight personnel, high-performance armed helicopter flight personnel, and other flight personnel meet the additional physical requirements outlined in the corresponding flight personnel standards; and (9) Completed ground observation period (≥ 6 months for low-risk, ≥ 12 months for intermediate/high-risk).

Appraisal agency

The initial medical assessment of special permission for flight shall be organized and conducted by the Air Force Medical Center (or a medical institution with the appropriate qualifications). The Flight Crew Medical Assessment Committee for Special Permission will hold personalized discussions for applicants who meet the above basic criteria and issue a conclusion of either “qualified for special permission for flight” or “unqualified for special permission for flight”. For subsequent assessments following initial qualification, conclusions of “flight qualified” or “temporarily flight unqualified” will be organized and evaluated by military medical institutions with aviation (special operations) departments. The conclusion of “flight unqualified” will be organized and evaluated by qualified medical institutions.

PREVENTION STRATEGIES AND HEALTH MANAGEMENT

Reducing risk factors

Ionizing radiation is a major risk factor for thyroid cancer in flight personnel. Primary prevention should focus on enhanced protection and minimized exposure, which can be achieved through measures such as: (1) Optimizing flight plans to reasonably reduce high-altitude flight time; (2) Avoiding high-radiation areas (such as polar routes) whenever possible; (3) Wearing radiation protective clothing; (4) Using personal radiation monitoring devices; and (5) Improving radiation protection designs for the cockpits of new fighter jets.

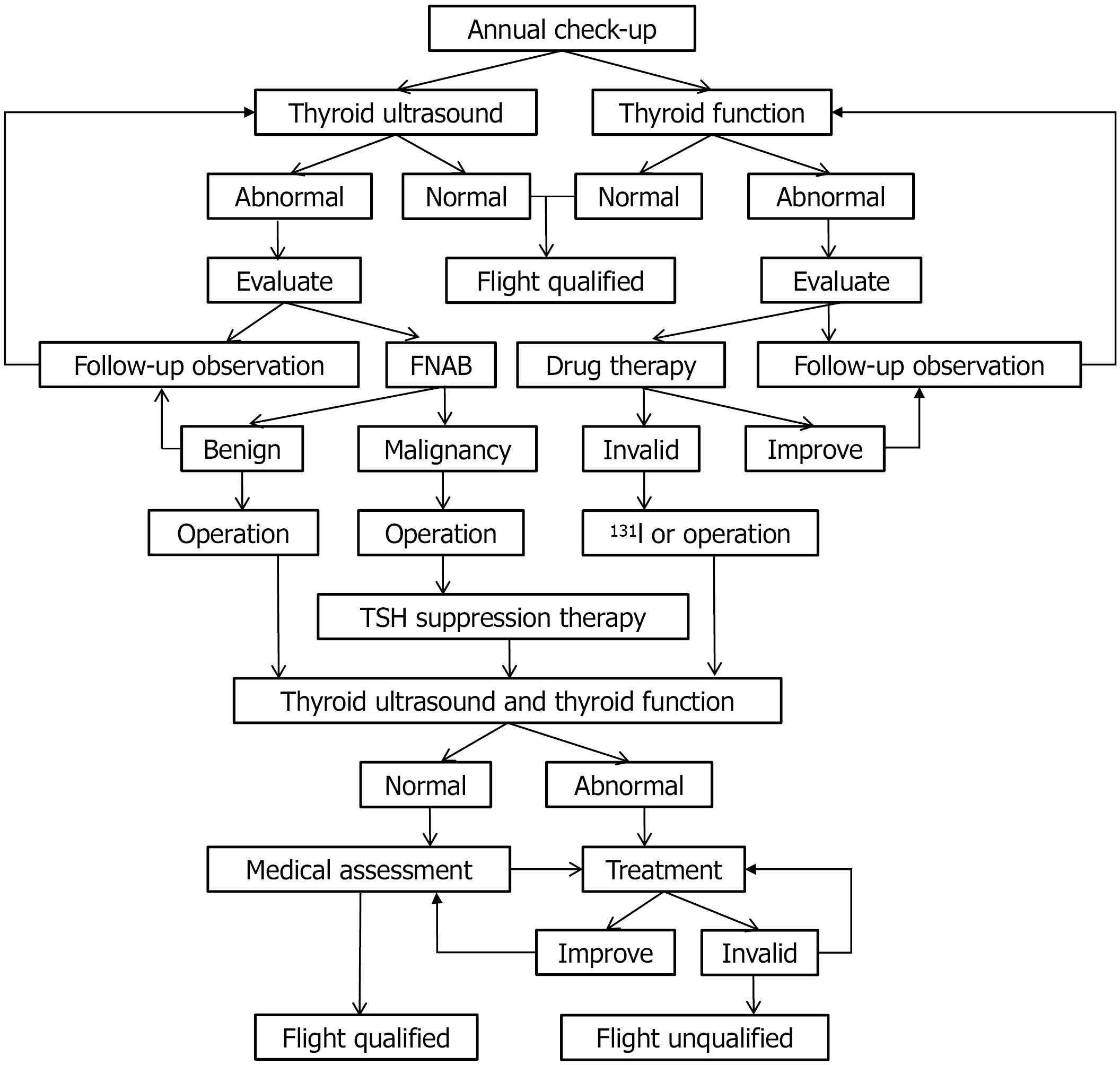

Another important risk factor is the long-term physiological and psychological stress. Therefore, for flight personnel, regular screening for psychological issues should be conducted to detect them early, followed by psychological counseling and rehabilitation therapy to alleviate these stressors. Additionally, public health education should be enhanced to guide flight personnel in maintaining a healthy lifestyle, controlling their weight[35], ensuring a balanced intake of iodine, quitting smoking, and limiting alcohol consumption (Figure 1).

Establishing a comprehensive screening system

It included: (1) Thyroid ultrasound examination has been included in the annual routine physical examinations for flight personnel; (2) The screening interval should be shortened for high-risk groups (flight personnel with more than 2000 hours of flight time, those with a family history, obese individuals, and early warning aircraft flight personnel); (3) New technologies, such as elastography and contrast-enhanced ultrasound, should be promoted to improve diagnostic accuracy; and (4) A follow-up database for thyroid nodules in flight personnel should be established. It is recommended to adopt a risk stratification management strategy, assess malignant risk based on ultrasonic characteristics and clinical factors, and create individualized follow-up plans.

Standardized treatment and rehabilitation

A multidisciplinary team model should be established, involving specialists from endocrinology, thyroid surgery, nuclear medicine, radiology, pathology, and aviation medicine. Individualized treatment plans shall be developed to eradicate the disease while maximizing the preservation of function. Postoperative rehabilitation guidance should be enhanced, including voice training, neck function exercises, calcium supplementation, and psychological counseling.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the prevention and treatment of thyroid cancer in military flight personnel require comprehensive planning and systematic implementation. By strengthening basic research, optimizing clinical management, refining assessment standards, and innovating health management protocols, a complete system encompassing “screening, diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation, and assessment” should be established (Figure 1). This integrated system will optimally safeguard the health and combat readiness of flight personnel, thereby providing robust support for the advancement of Chinese military aviation capabilities.

Figure 1 Flowchart for diagnosis, treatment, and certification of thyroid diseases in military flight personnel.

FNAB: Fine-needle aspiration biopsy; TSH: Thyroid-stimulating hormone.