Published online Feb 24, 2026. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v17.i2.116251

Revised: December 11, 2025

Accepted: January 14, 2026

Published online: February 24, 2026

Processing time: 92 Days and 14.8 Hours

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is an aggressive subtype with limited therapeutic options, primarily relying on chemotherapy, yet often leading to recurrence due to chemoresistance. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) contribute to tumor heterogeneity, resistance, and poor prognosis, but data in Pakistani populations are scarce. This study hypothesizes that a positive CSC phenotype independently predicts reduced pathological complete response (pCR) and inferior survival outcomes.

To investigate CSC markers’ association with chemotherapy response and survival in Pakistani TNBC patients.

Retrospective cohort study at Institute of Radiotherapy and Nuclear Medicine, Peshawar, Pakistan, including 256 women with TNBC from January 2015 to December 2022. CSC markers (CD44 high, CD24 low, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 positive) were assessed via immunohistochemistry on pre-treatment biopsies. Outcomes: pCR to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, overall survival, disease-free survival. Data were analyzed with multivariable logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards models, adjusting for age, tumor grade, and stage.

The CSC-positive phenotype was identified in 26 patients (10.2%). Compared to negative cases, positive cases had lower pCR rates [5.0% vs 51.8%; adjusted odds ratio = 0.05, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.01-0.39, P = 0.004]. The positive phenotype was associated with poorer overall survival (adjusted hazard ratio = 4.35, 95%CI: 2.43-7.79, P < 0.001), with a median overall survival of 19 months vs 27 months. No association with disease-free survival was observed (hazard ratio = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.43-1.73, P = 0.675).

CSC markers are associated with reduced chemotherapy response and inferior overall survival in Pakistani TNBC patients. These findings suggest their potential as prognostic biomarkers and highlight the need for future research into targeted strategies, such as proteomic profiling and Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras technology, to overcome chemoresistance in this population.

Core Tip: In a Pakistani triple-negative breast cancer cohort, the cancer stem cell phenotype (CD44 high/CD24 low/aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 positive) occurred in 10.2% of cases and independently predicted markedly lower pathological complete response (5.0% vs 51.8%) and shorter overall survival (hazard ratio = 4.35). These findings from a South Asian population with high triple-negative breast cancer burden support cancer stem cell marker integration into risk stratification for personalized therapy in resource-limited settings.

- Citation: Depar FN, Chaudhary AJ, Hameed J, Abbasi FS, Uzma B, Ali A, Akhtar N, Khan R, Siddiqi A, Riaz S. Cancer stem cell markers, chemotherapy response, and survival in triple-negative breast cancer. World J Clin Oncol 2026; 17(2): 116251

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v17/i2/116251.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v17.i2.116251

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) constitutes approximately 15%-20% of all breast malignancies and is characterized by the absence of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 expression. This subtype is recognized for its aggressive biological behavior, high propensity for early metastasis, and limited therapeutic options, primarily relying on cytotoxic chemotherapy. Despite initial sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents, a substantial proportion of TNBC patients experience disease recurrence, contributing to suboptimal five-year survival rates of approximately 77% for localized disease and markedly worse outcomes for advanced stages[1,2].

The heterogeneity of TNBC poses significant challenges to effective management. Emerging research has implicated cancer stem cells (CSCs) as pivotal contributors to this heterogeneity, driving tumor initiation, progression, therapeutic resistance, and relapse[3]. CSCs represent a minor subpopulation within tumors capable of self-renewal and differentiation, enabling them to repopulate the tumor mass following treatment. In breast cancer, particularly TNBC, CSCs are commonly identified by specific surface markers such as high expression of CD44 (a hyaluronan receptor involved in cell adhesion and signaling), low expression of CD24 (a glycoprotein associated with immune evasion), and positivity for aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1, an enzyme linked to detoxification and stemness)[4,5].

Preclinical investigations have elucidated mechanisms by which CSCs confer chemoresistance, including enhanced DNA repair, efflux pump activity, and quiescence, rendering them resilient to conventional agents like anthracyclines and taxanes[6,7]. Clinically, studies from Western populations have reported that TNBC tumors enriched with CSCs exhibit lower rates of pathological complete response (pCR) to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and are associated with inferior survival outcomes[8,9]. However, these findings may not fully extrapolate to diverse ethnic groups, where ge

In Pakistan, breast cancer is the most common malignancy among women, with TNBC comprising a disproportionately higher fraction (up to 30%) compared to global averages. It is often diagnosed at younger ages and advanced stages due to limited screening and healthcare access[11,12]. Data on CSC markers in this population are sparse, with preliminary reports suggesting potential ethnic variations in biomarker expression and clinical implications[13]. Addressing this knowledge gap is crucial for tailoring management strategies in resource-constrained settings, where biomarker-driven approaches could optimize resource allocation and improve patient outcomes.

This retrospective cohort study aims to evaluate the associations of CSC markers (CD44, CD24, ALDH1) with che

This retrospective cohort study was conducted in accordance with the STROBE guidelines for observational research[14]. Data were retrieved from the electronic medical records, pathology databases, and tumor registry at Institute of Radiotherapy and Nuclear Medicine, a tertiary care facility in Peshawar, Pakistan. The study period encompassed diagnoses from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2022, with follow-up data collected until November 3, 2025, to ensure adequate event ascertainment.

Eligibility criteria included female patients aged 20 years or older with histologically confirmed invasive TNBC. TNBC was defined as estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor expression < 1% by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 score of 0-1+ or non-amplified by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Patients must have received systemic chemotherapy (neoadjuvant or adjuvant) and had available pre-treatment tumor tissue for CSC marker evaluation. Exclusion criteria comprised stage IV disease at presentation, bilateral breast cancer, history of prior malignancy, or insufficient follow-up data (less than 12 months unless an event occurred). From an initial pool of 350 eligible cases identified in the hospital registry, 256 patients were selected through random sampling to ensure cohort representativeness and minimize selection bias (Supplementary Figure 1).

The primary exposure was the CSC phenotype, defined as positive if tumors exhibited high CD44 expression (≥ 50% membranous staining), low CD24 expression (< 10% staining), and ALDH1 positivity (> 5% cytoplasmic staining). This was assessed via IHC on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded pre-treatment core biopsies using standard protocols[4,15]. IHC was performed by board-certified pathologists blinded to clinical outcomes, with inter-observer agreement verified on a subset of samples (kappa > 0.8).

Outcome variables encompassed chemotherapy response and survival metrics. For patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy, pCR was defined as the absence of residual invasive carcinoma in the breast and axillary lymph nodes (ypT0/ypN0) according to the Residual Cancer Burden classification[16]. Survival outcomes included overall survival (OS) (time from diagnosis to death from any cause) and disease-free survival (DFS) (time from diagnosis to local/distant recurrence or death), with censoring at the last follow-up or study cutoff date.

Covariates were selected based on established prognostic factors in TNBC and included demographic variables (age at diagnosis, menopausal status), clinical features [Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, family history of breast cancer, breast cancer gene (BRCA) status such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 status if tested, comorbidities via Charlson Comorbidity Index], tumor characteristics [histological subtype, Nottingham grade, tumor size (T stage), nodal involvement (N stage), American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition stage (I-III), Ki-67 proliferation index], and treatment details [chemotherapy regimen (anthracycline-taxane based with or without platinum)], surgery type (mastectomy vs breast-conserving), receipt of radiation therapy].

Data abstraction was conducted by two independent reviewers using standardized extraction forms, with discrepancies resolved through consensus. Missing data rates were low (< 10% for core variables) and handled via complete-case analysis, supplemented by multiple imputation sensitivity analyses to assess robustness.

Selection bias was addressed through randomized sampling from the registry. Information bias was minimized by using validated pathology and clinical records, with double data entry for key variables. Confounding was controlled through multivariable modeling, incorporating clinically relevant covariates.

The sample size of 256 was determined a priori to provide 80% power to detect a hazard ratio (HR) of 2.0 for survival outcomes, assuming 30% event rate and 10%-15% CSC positivity, at a two-sided alpha of 0.05. Post-hoc power calculations confirmed adequate power for the observed HR of 4.35 in OS (power > 95%).

Descriptive statistics summarized baseline characteristics are mean ± SDs or medians with interquartile ranges for continuous variables, and n (%) for categorical ones. Group comparisons by CSC status utilized t-tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous data and χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical data.

Associations with pCR were evaluated using multivariable logistic regression, reporting adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Survival analyses employed Kaplan-Meier methods with log-rank tests for univariate comparisons and Cox proportional hazards models for multivariable assessments, yielding HRs with 95%CIs. Proportional hazards assumptions were verified via Schoenfeld residuals. Subgroup analyses explored heterogeneity by stage and chemotherapy type, with interaction terms tested.

All analyses were performed using R version 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with a significance threshold of P < 0.05. R code for key analyses is provided in the “Methods” section of the main text.

Of the 350 potentially eligible TNBC patients identified, 94 were excluded due to metastatic disease (n = 50), incomplete records (n = 30), or lack of CSC assessment (n = 14), resulting in a final cohort of 256 (Supplementary Figure 1). The median follow-up duration was 32 months (interquartile range: 18-48 months), with a total of 8192 person-months of observation. Missing data were noted for BRCA status (60%), comorbidities (20%), and performance status (15%), but core variables for analysis were complete.

The cohort had a median age of 47 years (standard deviation = 9.5), with 135 (52.7%) premenopausal women. Most tumors were high-grade (grade 3: 56.5%), stage II-III (70%), and invasive ductal histology (85%). Neoadjuvant che

CSC-positive phenotype was observed in 26 patients (10.2%), with individual marker distributions: CD44 high in 55%, CD24 low in 48%, and ALDH1 positive in 38%. Baseline characteristics stratified by CSC status are detailed in Table 1, with no statistically significant differences. For instance, mean age was 45.3 years in CSC-positive vs 46.8 years in CSC-negative groups (P = 0.457), and stage distribution was comparable (P = 0.666).

| Characteristic | CSC-negative (n = 230) | CSC-positive (n = 26) | P value |

| Age, mean (SD) | 46.8 (9.4) | 45.3 (10.4) | 0.457 |

| Menopausal status | 0.116 | ||

| Pre | 117 (50.9) | 18 (69.2) | |

| Post | 113 (49.1) | 8 (30.8) | |

| Tumor grade | 0.198 | ||

| 1 | 33 (14.3) | 6 (23.1) | |

| 2 | 67 (29.1) | 10 (38.5) | |

| 3 | 130 (56.5) | 10 (38.5) | |

| Stage | 0.666 | ||

| I | 68 (29.6) | 8 (30.8) | |

| II | 72 (31.3) | 10 (38.5) | |

| III | 90 (39.1) | 8 (30.8) | |

| Ki-67, mean (SD) | 42.7 (13.4) | 38.0 (11.7) | 0.088 |

| Chemotherapy type | 0.708 | ||

| Neoadjuvant | 164 (71.3) | 20 (76.9) | |

| Adjuvant | 66 (28.7) | 6 (23.1) | |

| Surgery | 0.847 | ||

| Mastectomy | 141 (61.3) | 17 (65.4) | |

| Breast-conserving | 89 (38.7) | 9 (34.6) | |

| Radiation | 189 (82.2) | 21 (80.8) | 1.000 |

Among the 184 patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy, pCR was achieved in 86 (46.7%). CSC-positive patients demonstrated substantially lower pCR rates (1/20, 5.0%) compared to CSC-negative (85/164, 51.8%). In multivariable logistic regression adjusting for age, grade, and stage, CSC positivity was independently associated with reduced odds of pCR (adjusted OR = 0.05, 95%CI: 0.01-0.39, P = 0.004; Table 2). Other covariates did not significantly influence response.

| Variable | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | P value |

| CSC positive | 0.05 (0.01-0.39) | 0.004 |

| Age (per year) | 1.00 (0.97-1.03) | 0.937 |

| Grade (per level) | 1.10 (0.67-1.81) | 0.664 |

| Stage II (vs I) | 1.48 (0.66-3.29) | 0.337 |

| Stage III (vs I) | 1.03 (0.49-2.16) | 0.944 |

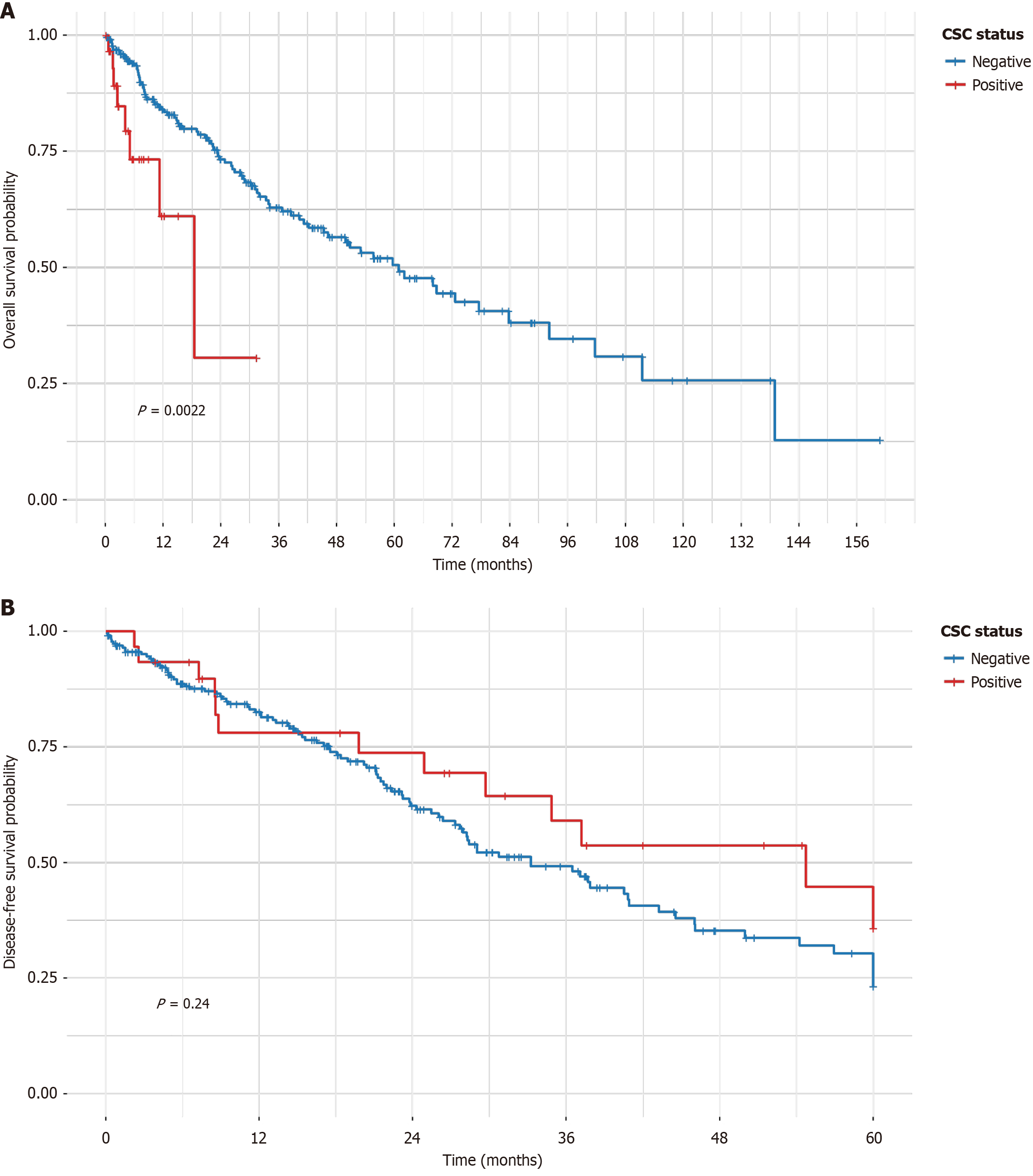

During follow-up, 90 OS events (35.2%) and 110 DFS events (43.0%) were recorded. Median OS was 25 months overall, with CSC-positive patients exhibiting shorter median OS (19 months) than CSC-negative (27 months). Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed significantly worse OS in the CSC-positive group (log-rank P < 0.0022; Figure 1A), but no difference in DFS (log-rank P = 0.67; Figure 1B). In contrast, the multivariable Cox model, which adjusted for age, grade, and stage, demonstrated an even stronger association (adjusted HR = 4.35, 95%CI: 2.43-7.79, P < 0.001; Table 3). Supplementary Figure 2 for forest plot, independent of age, grade, and stage. For DFS, no significant association was observed (adjusted HR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.43-1.73, P = 0.675; Table 4). Subgroup analyses by stage demonstrated consistent HRs for OS across strata (Supplementary Table 1), with no evidence of interaction (P > 0.05). Sensitivity analyses using multiple imputation for missing data yielded similar results, confirming robustness.

| Variable | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | P value |

| CSC positive | 4.35 (2.43-7.79) | < 0.001 |

| Age (per year) | 1.00 (0.98-1.03) | 0.833 |

| Grade (per level) | 0.98 (0.74-1.30) | 0.879 |

| Stage II (vs I) | 0.83 (0.48-1.42) | 0.497 |

| Stage III (vs I) | 0.96 (0.58-1.60) | 0.887 |

| Variable | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | P value |

| CSC positive | 0.86 (0.43-1.73) | 0.675 |

| Age (per year) | 1.01 (0.99-1.03) | 0.274 |

| Grade (per level) | 1.31 (0.98-1.74) | 0.068 |

| Stage II (vs I) | 0.92 (0.57-1.48) | 0.721 |

| Stage III (vs I) | 0.80 (0.50-1.30) | 0.369 |

In this retrospective cohort study of 256 Pakistani women with TNBC, we demonstrated that a positive CSC phenotype - defined by high CD44, low CD24, and ALDH1 positivity - is associated with markedly reduced pCR to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and inferior OS, independent of traditional clinicopathologic factors. These results underscore the prognostic relevance of CSC markers in an understudied population, where TNBC burden is high and outcomes are often compromised by socioeconomic barriers[11,12].

The observed CSC positivity rate of 10.2% is somewhat lower than reported in Western cohorts (20%-30%)[4,8], While this suggests potential ethnic variations, direct comparisons with other Asian populations are limited by the small sample size of the CSC-positive subgroup in our study and the lack of standardized detection methods across regional studies. South Asian TNBC frequently harbors basal-like features and BRCA mutations, which may modulate CSC expression[10,13]. These genetic factors may enhance CSC plasticity, facilitating the transition to a CD44+/CD24- phenotype that promotes chemoresistance through improved DNA repair mechanisms and metabolic adaptation, a phenomenon that warrants specific investigation in this ethnic subgroup. Nonetheless, the strong negative association with pCR (adjusted OR = 0.05) aligns with prior evidence that CSCs evade chemotherapy through mechanisms like enhanced aldehyde dehydrogenase activity for drug detoxification and CD44-mediated survival signaling[5,6]. This chemoresistance likely contributes to residual disease, a known harbinger of relapse in TNBC[16].

Regarding survival, the fourfold increased OS hazard in CSC-positive patients (HR = 4.35) corroborates meta-analyses linking CSC markers to poor prognosis[9,17] and recent studies showing ALDH1 overexpression correlated with reduced survival[18]. The combined CD44hi/CD24 Lo-ALDH1hi phenotype has been identified as an independent prognostic factor post-neoadjuvant therapy[19]. The lack of DFS association (HR = 0.86) is intriguing and may reflect differential impacts on distant vs local recurrence, competing risks in our cohort (e.g., comorbidities in low-resource settings), or insufficient power given the small CSC-positive subgroup[20]. Alternatively, CSC-driven metastases could manifest later, necessitating longer follow-up[21].

Mechanistically, CSCs promote tumor heterogeneity and therapeutic failure by self-renewing and differentiating into bulk tumor cells post-treatment[3,7]. In TNBC, CSC enrichment after chemotherapy has been documented, supporting adaptive resistance[22]. Recent reviews highlight CSC plasticity as a key driver of chemoresistance in TNBC[23], with ALDH1A3 regulating CSC populations and metabolism[24]. Our findings extend this to a real-world Pakistani context, where younger presentation (median age 47 years) and advanced stages (70% II-III) mirror national trends[11]. The independent prognostic value of CSC markers suggests they could augment existing tools like Ki-67 or gene expression profiles for risk stratification[25].

Comparatively, studies from similar low-middle income countries report analogous CSC associations but with varying prevalences, emphasizing the need for region-specific validation[26]. For instance, an Indian cohort found ALDH1 positivity linked to worse DFS, contrasting our OS-focused results, possibly due to differences in follow-up or regimens[27]. A 2024 study on CD44 in TNBC suggested its prognostic value[28], while another profiling CSC markers reinforced the role of CD44/CD24-ALDH1 combinations[29]. Integration with molecular subtyping (e.g., Lehmann classifications) could further refine these insights[30].

Strengths include the single-center design ensuring consistent pathology and treatment protocols, randomized sampling to enhance representativeness, rigorous statistical adjustments per STROBE guidelines[14], and sensitivity analyses for missing data. The use of a composite CSC phenotype, rather than isolated markers, captures stemness more comprehensively[4].

Limitations inherent to retrospective designs include potential selection bias, though mitigated by sampling, and information bias from record incompleteness (e.g., high missing BRCA data, addressed via imputation). Specifically, a significant limitation is the high rate of missing data for BRCA status (60%), which restricts our ability to fully explore the genetic drivers of CSCs in this population. IHC interpretation subjectivity was addressed through blinding and kappa assessment. However, our study is limited by the lack of functional assays (e.g., mammosphere formation) or molecular validation (e.g., qPCR) to confirm the biological stemness of the IHC-defined phenotype, as fresh tissue was unavailable due to the retrospective study design[31]. The modest CSC-positive sample (n = 26) constrained subgroup analyses and power for DFS, and unmeasured confounders like socioeconomic status or access to care may influence generalizability[32]. Single-center data from an urban tertiary facility may not reflect rural Pakistani experiences, and the lower CSC positivity rate compared to some studies warrants caution in extrapolation.

These results support the potential for routine CSC marker assessment in TNBC to identify high-risk patients warranting intensified surveillance or novel therapies. Targeting CSCs with agents like ALDH inhibitors, CD44 antagonists, or immunotherapies (e.g., anti-programmed death-ligand 1) could synergize with chemotherapy, as evidenced by preclinical models[33,34]. In resource-limited Pakistan, cost-effective IHC-based prognostication could prioritize patients for clinical trials or palliative care. Furthermore, cutting-edge strategies such as Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras offer the potential to degrade previously “undruggable” CSC targets, including the CD44/ALDH1 axis, representing a promising translational avenue for overcoming resistance in high-risk populations. While our focus remains on solid tumors, the success of novel biological therapies in other hematological malignancies, such as ropeginterferon alfa-2b for polycythemia vera, highlights the potential of targeted immunomodulation to improve long-term outcomes in difficult-to-treat cancers[35]. This aligns with broader oncological trends where identifying precise clinicopathological predictors for metastasis - recently highlighted in papillary thyroid carcinoma[36] - remains pivotal for optimizing surgical and systemic management, mirroring our findings in TNBC.

Future prospective studies should validate these associations in larger, multicenter cohorts, incorporating serial CSC evaluations, genomic profiling, and functional assays to elucidate ethnic-specific mechanisms[37]. Interventional trials testing CSC-directed strategies in South Asian TNBC are imperative to translate biomarkers into improved survival[38].

In conclusion, CSC markers are associated with adverse outcomes in Pakistani TNBC, highlighting opportunities for personalized medicine in stem cell-driven cancers. Future research should employ proteomic techniques and Proteolysis Targeting Chimera probe technology to unravel the molecular mechanisms underlying CSC-mediated chemoresistance in Pakistani TNBC, moving beyond descriptive associations to target validation.

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68741] [Article Influence: 13748.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (201)] |

| 2. | Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, Hanna WM, Kahn HK, Sawka CA, Lickley LA, Rawlinson E, Sun P, Narod SA. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4429-4434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2803] [Cited by in RCA: 3720] [Article Influence: 195.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Batlle E, Clevers H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nat Med. 2017;23:1124-1134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1234] [Cited by in RCA: 2018] [Article Influence: 224.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3983-3988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7830] [Cited by in RCA: 7800] [Article Influence: 339.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E, Monville F, Dutcher J, Brown M, Jacquemier J, Viens P, Kleer CG, Liu S, Schott A, Hayes D, Birnbaum D, Wicha MS, Dontu G. ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:555-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3173] [Cited by in RCA: 3109] [Article Influence: 163.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li X, Lewis MT, Huang J, Gutierrez C, Osborne CK, Wu MF, Hilsenbeck SG, Pavlick A, Zhang X, Chamness GC, Wong H, Rosen J, Chang JC. Intrinsic resistance of tumorigenic breast cancer cells to chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:672-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1319] [Cited by in RCA: 1379] [Article Influence: 76.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Creighton CJ, Li X, Landis M, Dixon JM, Neumeister VM, Sjolund A, Rimm DL, Wong H, Rodriguez A, Herschkowitz JI, Fan C, Zhang X, He X, Pavlick A, Gutierrez MC, Renshaw L, Larionov AA, Faratian D, Hilsenbeck SG, Perou CM, Lewis MT, Rosen JM, Chang JC. Residual breast cancers after conventional therapy display mesenchymal as well as tumor-initiating features. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13820-13825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1015] [Cited by in RCA: 1109] [Article Influence: 65.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Idowu MO, Kmieciak M, Dumur C, Burton RS, Grimes MM, Powers CN, Manjili MH. CD44(+)/CD24(-/low) cancer stem/progenitor cells are more abundant in triple-negative invasive breast carcinoma phenotype and are associated with poor outcome. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:364-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yang L, Hu X, Ye X, Zhang W, Peng X. Clinicopathological and Prognostic Significance of Cancer Stem Cell Markers in Patients with Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2025;32:7059-7067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Adrada BE, Moseley TW, Kapoor MM, Scoggins ME, Patel MM, Perez F, Nia ES, Khazai L, Arribas E, Rauch GM, Guirguis MS. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Histopathologic Features, Genomics, and Treatment. Radiographics. 2023;43:e230034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Reddy GM, Suresh PK, Pai RR. Clinicopathological Features of Triple Negative Breast Carcinoma. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:EC05-EC08. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Agarwal G, Nanda G, Lal P, Mishra A, Agarwal A, Agrawal V, Krishnani N. Outcomes of Triple-Negative Breast Cancers (TNBC) Compared with Non-TNBC: Does the Survival Vary for All Stages? World J Surg. 2016;40:1362-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hashmi AA, Edhi MM, Naqvi H, Faridi N, Khurshid A, Khan M. Clinicopathologic features of triple negative breast cancers: an experience from Pakistan. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6805] [Cited by in RCA: 13721] [Article Influence: 722.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 15. | Ricardo S, Vieira AF, Gerhard R, Leitão D, Pinto R, Cameselle-Teijeiro JF, Milanezi F, Schmitt F, Paredes J. Breast cancer stem cell markers CD44, CD24 and ALDH1: expression distribution within intrinsic molecular subtype. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:937-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 458] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Symmans WF, Peintinger F, Hatzis C, Rajan R, Kuerer H, Valero V, Assad L, Poniecka A, Hennessy B, Green M, Buzdar AU, Singletary SE, Hortobagyi GN, Pusztai L. Measurement of residual breast cancer burden to predict survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4414-4422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 963] [Cited by in RCA: 1223] [Article Influence: 64.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Qiao GL, Song LN, Deng ZF, Chen Y, Ma LJ. Prognostic value of CD44v6 expression in breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:5451-5457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yang Y, Li Z, Zhu Y, Guo C, Yang L, Zhang J. Clinical significance and expression of ALDH1 in triple-negative breast cancer. Diagn Pathol. 2025;20:117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ghebeh H, Mirza JY, Al-Tweigeri T, Al-Alwan M, Tulbah A. Profiling of Breast Cancer Stem Cell Types/States Shows the Role of CD44(hi)/CD24(lo)-ALDH1(hi) as an Independent Prognostic Factor After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:8219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496-509. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Sheridan C, Kishimoto H, Fuchs RK, Mehrotra S, Bhat-Nakshatri P, Turner CH, Goulet R Jr, Badve S, Nakshatri H. CD44+/CD24- breast cancer cells exhibit enhanced invasive properties: an early step necessary for metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8:R59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 702] [Cited by in RCA: 761] [Article Influence: 40.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yu F, Yao H, Zhu P, Zhang X, Pan Q, Gong C, Huang Y, Hu X, Su F, Lieberman J, Song E. let-7 regulates self renewal and tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells. Cell. 2007;131:1109-1123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1416] [Cited by in RCA: 1489] [Article Influence: 82.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Guo Z, Han S. Targeting cancer stem cell plasticity in triple-negative breast cancer. Explor Target Antitumor Ther. 2023;4:1165-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fernando W, Cruickshank BM, Arun RP, MacLean MR, Cahill HF, Morales-Quintanilla F, Dean CA, Wasson MD, Dahn ML, Coyle KM, Walker OL, Power Coombs MR, Marcato P. ALDH1A3 is the switch that determines the balance of ALDH(+) and CD24(-)CD44(+) cancer stem cells, EMT-MET, and glucose metabolism in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2024;43:3151-3169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lehmann BD, Bauer JA, Chen X, Sanders ME, Chakravarthy AB, Shyr Y, Pietenpol JA. Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2750-2767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3591] [Cited by in RCA: 4164] [Article Influence: 277.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Nagalla S, Chou JW, Willingham MC, Ruiz J, Vaughn JP, Dubey P, Lash TL, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Bergh J, Sotiriou C, Black MA, Miller LD. Interactions between immunity, proliferation and molecular subtype in breast cancer prognosis. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Croker AK, Goodale D, Chu J, Postenka C, Hedley BD, Hess DA, Allan AL. High aldehyde dehydrogenase and expression of cancer stem cell markers selects for breast cancer cells with enhanced malignant and metastatic ability. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:2236-2252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 350] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Punhani P, Ahluwalia C, Agrawal M, Kandwal P. Expression of CD44 in Triple Negative Breast Cancer and its Correlation with Prognostic Parameters. Arch Breast Cancer. 2024;11:371-377. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Bharadwaj AG, McLean ME, Dahn ML, Cahill HF, Wasson MD, Arun RP, Walker OL, Cruickshank BM, Fernando W, Venkatesh J, Barnes PJ, Bethune G, Knapp G, Helyer LK, Giacomantonio CA, Waisman DM, Marcato P. ALDH1A3 promotes invasion and metastasis in triple-negative breast cancer by regulating the plasminogen activation pathway. Mol Oncol. 2024;18:91-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Anurag M, Jaehnig EJ, Krug K, Lei JT, Bergstrom EJ, Kim BJ, Vashist TD, Huynh AMT, Dou Y, Gou X, Huang C, Shi Z, Wen B, Korchina V, Gibbs RA, Muzny DM, Doddapaneni H, Dobrolecki LE, Rodriguez H, Robles AI, Hiltke T, Lewis MT, Nangia JR, Nemati Shafaee M, Li S, Hagemann IS, Hoog J, Lim B, Osborne CK, Mani DR, Gillette MA, Zhang B, Echeverria GV, Miles G, Rimawi MF, Carr SA, Ademuyiwa FO, Satpathy S, Ellis MJ. Proteogenomic Markers of Chemotherapy Resistance and Response in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:2586-2605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Chaffer CL, Brueckmann I, Scheel C, Kaestli AJ, Wiggins PA, Rodrigues LO, Brooks M, Reinhardt F, Su Y, Polyak K, Arendt LM, Kuperwasser C, Bierie B, Weinberg RA. Normal and neoplastic nonstem cells can spontaneously convert to a stem-like state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7950-7955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 842] [Cited by in RCA: 899] [Article Influence: 59.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zaidi AA, Ansari TZ, Khan A. The financial burden of cancer: estimates from patients undergoing cancer care in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11:60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yin H, Glass J. The phenotypic radiation resistance of CD44+/CD24(-or low) breast cancer cells is mediated through the enhanced activation of ATM signaling. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1938-1948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2585] [Cited by in RCA: 3183] [Article Influence: 198.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Tom L, Mani S, Rawat A, Nan M, Mundada SM, Al Khatib B, Gopinath A, Taj O, Salahuddin N, Shaju F, Parsa S, Abdurrahman M, Das A, Khawar MMH, Sher A. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b vs standard therapy in polycythemia vera: A meta-analysis of efficacy and safety outcomes. World J Clin Oncol. 2025;16:112392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Khawar MMH, Abid MH, Cheema MBA, Khawar M, Shaukat M, Khan MHA, Saifullah M, Noureen R, Khail HA, Qureshi AA, Khokhar MA. Clinicopathological predictors of right para esophageal lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Clin Oncol. 2025;16:110792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Oakman C, Viale G, Di Leo A. Management of triple negative breast cancer. Breast. 2010;19:312-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Liedtke C, Mazouni C, Hess KR, André F, Tordai A, Mejia JA, Symmans WF, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Hennessy B, Green M, Cristofanilli M, Hortobagyi GN, Pusztai L. Response to neoadjuvant therapy and long-term survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1275-1281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2098] [Cited by in RCA: 2193] [Article Influence: 121.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/