Published online Feb 24, 2026. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v17.i2.113428

Revised: October 14, 2025

Accepted: January 4, 2026

Published online: February 24, 2026

Processing time: 165 Days and 4 Hours

Colorectal cancer (CRC), encompassing both colon and rectal carcinogenesis, is a major health concern. Metastatic CRC (mCRC) is the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in United States adults. Despite advances in therapy, the 5-year survival rate remains low at 15%. KRAS mutations contribute to treatment resistance by altering the tumor microenvironment, necessitating novel therapeutic approaches.

To evaluate immunomodulatory and cytotoxic potential of reovirus as an adju

Five KRAS-mutant mCRC patients were treated with reovirus. Serum samples were collected at five time points over 15 days. Cytokine levels were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and transcriptomic profiling was performed to assess gene expression. Data were analyzed using the 2-ΔΔCt method, and statistical significance was determined via two-tailed t-tests (P < 0.05).

Out of 271 genes associated with Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription, Ras, Wnt, and phosphoinositide 3-kinase- alpha serine/threonine-protein kinase pathways, 85 showed significant modulation. Additionally, 17 of 25 cytokines were significantly altered. Reovirus induced changes in both gene and cytokine expression, sugges

Reovirus demonstrates potential as an immunomodulatory and cytotoxic adjuvant in KRAS-mutant mCRC by al

Core Tip: This study highlights the prospective of reovirus as both an immunomodulatory agent and a cytotoxic adjuvant to chemotherapy in patients with KRAS-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer. Reovirus induces anti-tumor immunity by mo

- Citation: Zweig V, Goel S, Maitra R. Gene and cytokine expression profiles of metastatic colorectal cancer patients post reovirus administration. World J Clin Oncol 2026; 17(2): 113428

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v17/i2/113428.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v17.i2.113428

Metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) is the fourth most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death for adults in the United States[1]. The standard in front line therapies for patients diagnosed with mCRC include the infusion of the following chemotherapeutic agents: 5-fluorouracil/Leucovorin with either oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) or irinotecan (FOLFIRI)[2].

Patients treated with FOLFOX and FOLFIRI have a progression-free survival of 9 months and 7 months respectively[2]. These new treatment strategies are embraced as the current standard of care, improving the overall survival rate of mCRC up to three years compared to six months with the best supportive care[2].

In recent years, efforts have increasingly focused on personalizing mCRC treatment by identifying appropriate patient subsets for specific therapies, aiming to optimize clinical outcomes[3,4]. The development of biological agents has further altered the landscape of mCRC treatment; the addition of inhibitors of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) has resulted in significantly longer median overall survival[3].

In spite of the aforementioned therapeutic advancements in chemotherapeutic drugs and biological inhibitors, the 5-year survival rate for mCRC patients remains at 15%[1]. Certain patients do not respond robustly to current therapies, and it is thought that this resistance is a result of differences in the tumor microenvironment (TME)[1,4].

The RAS oncogene has a well-established role in cell growth and regulation; its protein product influences many cellular functions including cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and differentiation[5,6]. The RAS oncogene presents itself in three different isoforms, which are KRAS, HRAS, and NRAS. The human isoform of the RAS oncogene, KRAS, is mutated in about 45% of colorectal cancers and the mutation is linked to more rapid and metastatic behavior and is associated with a poorer prognosis[5]. Normally, RAS proteins exist in an inactive state in any given cell and become activated when a nearby transmembrane receptor is bound by its corresponding ligand[5].

The resulting intracellular signaling cascade involves guanine nucleotide exchange factors, which activate RAS by replacing the bound GDP with GTP[5]. Once GTP bound, RAS confers to the downstream activation of various effectors that regulate cell growth and regulation. RAS is deactivated when the GTP molecule is converted back to a GDP mole

Furthermore, the KRAS gene has been implicated in the decreased response rates to select agents such as the anti-EGFR drugs cetuximab and panitumumab, which is commonly used in combination with FOLFOX and FOLFIRI. Typically, upon activation of EGFR, KRAS is activated downstream and results in cellular signaling cascades anti-EGFR drugs block this receptor to prevent the activation of this signaling cascade. However, KRAS mutations render these drugs ineffective by continuously activating signaling cascades despite inhibition proximal to the receptor[4,7]. Therefore, there is a clear demand for an alternative therapy that can more effectively treat KRAS mutant mCRC patients.

Viruses have distinct strategies that they use to overcome the sophisticated defense mechanisms of the infected host, and many have been identified as therapeutically viable oncolytic elements. One important member of therapeutically identified viruses is oncolytic reovirus (a naturally occurring, ubiquitous double-stranded RNA virus)[7]. Reovirus is naturally oncolytic with the ability to replicate in cells containing dysfunctional signaling cascades, including those with KRAS mutations, and is emerging as a potential therapy for KRAS mutant mCRC[7,8].

Therapeutic intervention with reovirus has profound consequences on the host immune profile. However, the modification of gene and cytokine expression due to reovirus has been under-studied. A crucial feature of inter-cellular communication is the production and release of small signaling molecules called cytokines. Cytokine profiles provide invaluable information about the molecular mechanisms driving tumor development, progression, and response to treatment. These molecules provide insights for prognosis and personalized therapy by facilitating the identification of biomarkers associated with different cancer stages and treatment outcomes. Investigating the cytokine expression profile of KRAS-mutant mCRC post-reovirus administration is crucial in understanding and assessing the treatment’s effect on tumor growth, progression, immune response, and the efficacy of reovirus as a therapeutic agent. This paper explores the effect of treatment with reovirus at transcriptional and translational levels by monitoring the expression of 25 cytokines that includes pro-inflammatory, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, immune cell activators/growth factors (Supplementary Table 1) that play critical roles in tumor development, progression, and immune response. We examined the release of serum cytokines using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method and the modulation of gene expression by transcriptome analysis over 15 days. We then examined the expression of 271 genes associated with several major, well-known signaling pathways, including RAS, Wnt, Janus kinase(JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-alpha serine/threonine-protein kinase (AKT), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, mechanistic target of rapamycin, and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-кB). The potential interactions between gene and cytokine expression are then discussed.

This study obtained serum samples from 5 patients, each having KRAS-mutated mCRC. All had received reovirus as part of a phase 1 clinical trial (NCT01274624; 11) in combination with standard of care FOLFIRI and bevacizumab.

Oncolytics Biotech, Inc. supplied reovirus as a translucent to clear, colorless, to light blue liquid in vials containing 7.2 × 1011 tissue culture infective dose per mL of reovirus in a phosphate-buffered solution, stored at -70 °C. For 5 consecutive days every 28 days, reovirus was administered as a 60-minute infusion at a tissue culture infective dose of 3 × 1010/day. Plasma was collected from each patient pre-reovirus, at 24 hours, 2 days, 7 days, and 14 days after the first dose of reo

An ELISA based cytokine assay was performed on serum/plasma samples obtained from five patients treated with reovirus. The samples were centrifuged at 12500 × g for 25 minutes, after which 50 μL of clarified plasma was transferred into each well of a 96 well plate for analysis. Next, beads (EMD Millipore) were coated 25 different cytokines (the cytokines included in Cat# HCYTOMAG60K25 panel is listed in Table 1). An EMD Millipore multiplex Luminex platform was used to assess cytokine expression profiles. Data from one patient who received reovirus was excluded from this analysis because most Luminex outputs were below the detection limit for all cytokines. For the remaining patients, all measurements were normalized to their respective pre-reovirus administration values, which served as controls for this study.

| Category | Cytokines/chemokines |

| IL | IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 (p40), IL-12 (p70), IL-13, IL-15, IL-17A |

| Growth factors | GM-CSF, VEGF |

| Interferons | IFN-α2, IFN-γ |

| TNF | TNF-α |

| Chemokines | MCP-1, MCP-3, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES |

Total RNA was isolated from reovirus administered five patients three patients receiving background therapy only. Single-stranded cDNA synthesis was performed following fragmentation and labeling using ThermoFisher Scientific Clariom D Pico Assay (Human, Catalog No. 902924). RNA was reverse transcribed via a priming method employing engineered primers designed to exclude ribosomal RNA sequences. Both poly(A) and non-poly(A) mRNA - were converted into double-stranded cDNA using first- and second-strand enzymes provided in the kit. These templates underwent in vitro transcription at 37 °C for 16 hours to generate cRNA. Subsequently, a hybridization cocktail (Catalog No. 900454) was used to produce single stranded complimentary DNA from cRNA through chemical fragmentation followed by biotin labeling. The single stranded complimentary DNA was hybridized to the Clariom D GeneChip probe array in strict accordance with the Affymetrix GeneChip protocol. Array imaging was performed using a high-resolution GeneArray Scanner 3000 7G (ThermoFisher Scientific, Santa Clara, CA, United States). In this study, 271 immune-related genes (Supplementary Table 2) were analyzed, comparing post-reovirus treatment samples collected on days 2, 8, and 15 to pre-treatment samples. Significant changes in gene expression (P < 0.05) were reported as up- or down-regulated, and notable genes were further examined.

Sample signals from individual patient on given time points was retrieved. The software used was developed by The

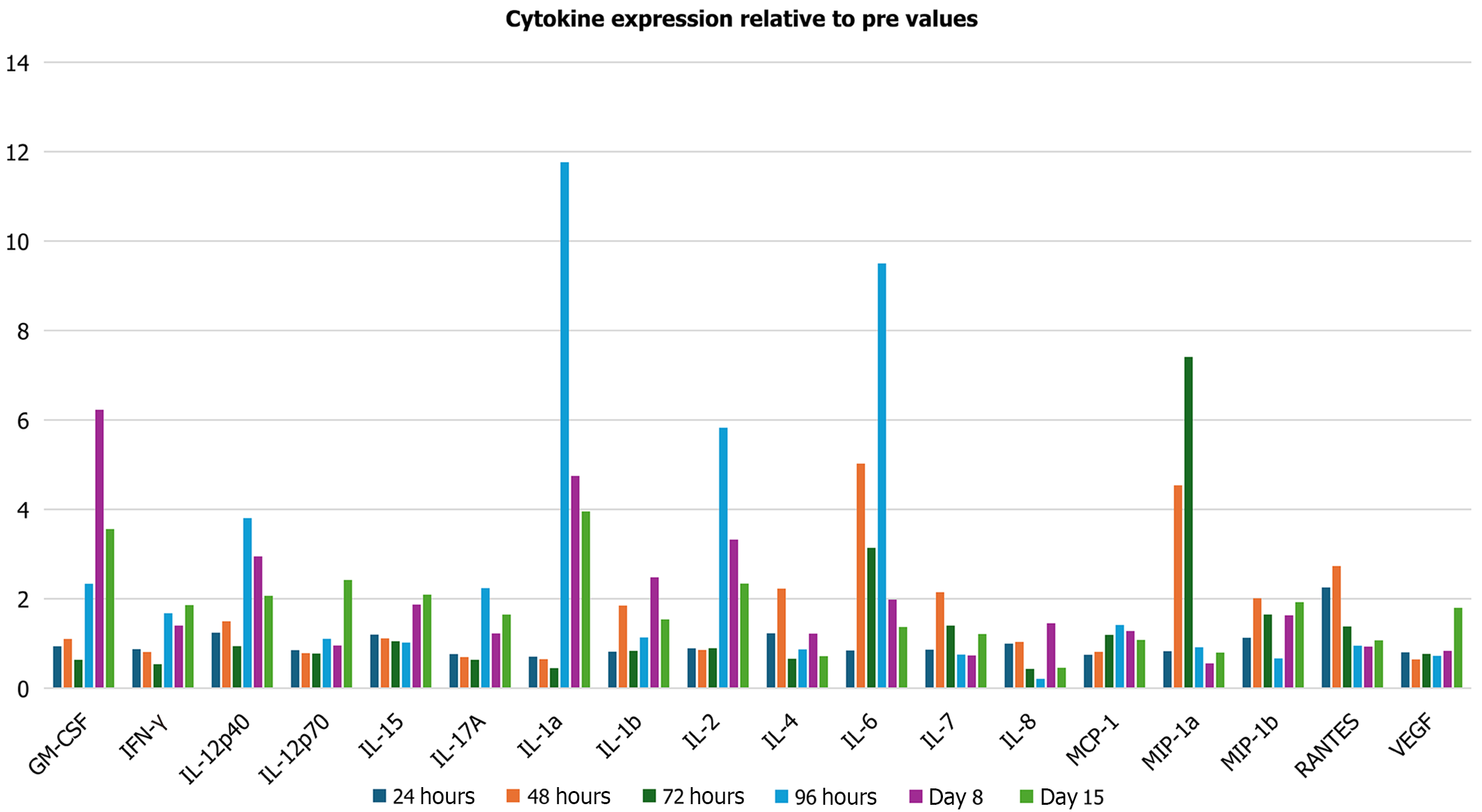

Cytokine expression determined at days 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, and 15 showed that 17 of 25 examined cytokines were significantly altered post-reovirus administration (P < 0.05) (Figure 1). Notable anti-tumorigenic cytokines were upregulated, and notable pro-tumorigenic cytokines were downregulated. An upregulation (relative to baseline) in the levels of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and interleukin (IL)-6 occurred during the 15-day period. Statistically significant increases were observed on day 15 for IFN-γ (1.86-fold change; P = 0.0004) and 8 for IL-6 (1.98-fold change; P = 0.0001). An overall decrease (relative to baseline) in the levels of VEGF, IL-8, and regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) occurred during the 15-day period. Statistically significant decreases were observed for VEGF at 24 hours (0.80, P = 0.0003), day 2 (0.64-fold change; P = 0.007), and day 3 (0.77-fold change; P = 0.002).

We next performed a comprehensive transcriptome analysis of the expression of cytokine-specific genes and their associated pathways at three time points: Days 2, 8, and 15. Overall, 109 genes of the Ras, 11 genes of the JAK-STAT, 9 genes of the PI3K/1, and 142 Wnt pathways were examined (Supplementary Table 2). Significant alterations in 21 genes of the Ras pathway, 6 genes of the JAK-STAT pathway, 9 genes of the PI3K/AKT pathway, and 45 genes of the Ras pathway were observed (Supplementary Tables 3-6).

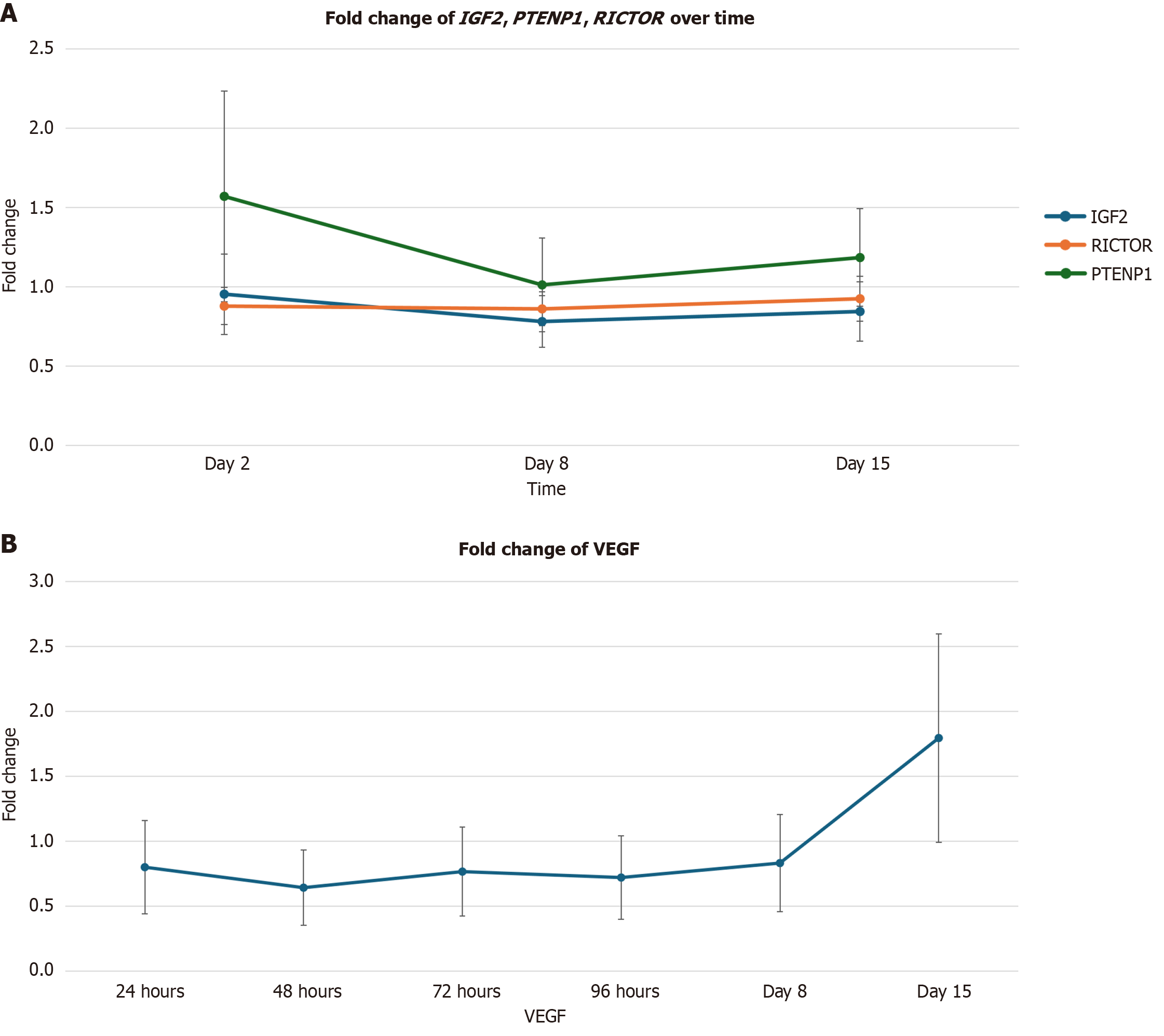

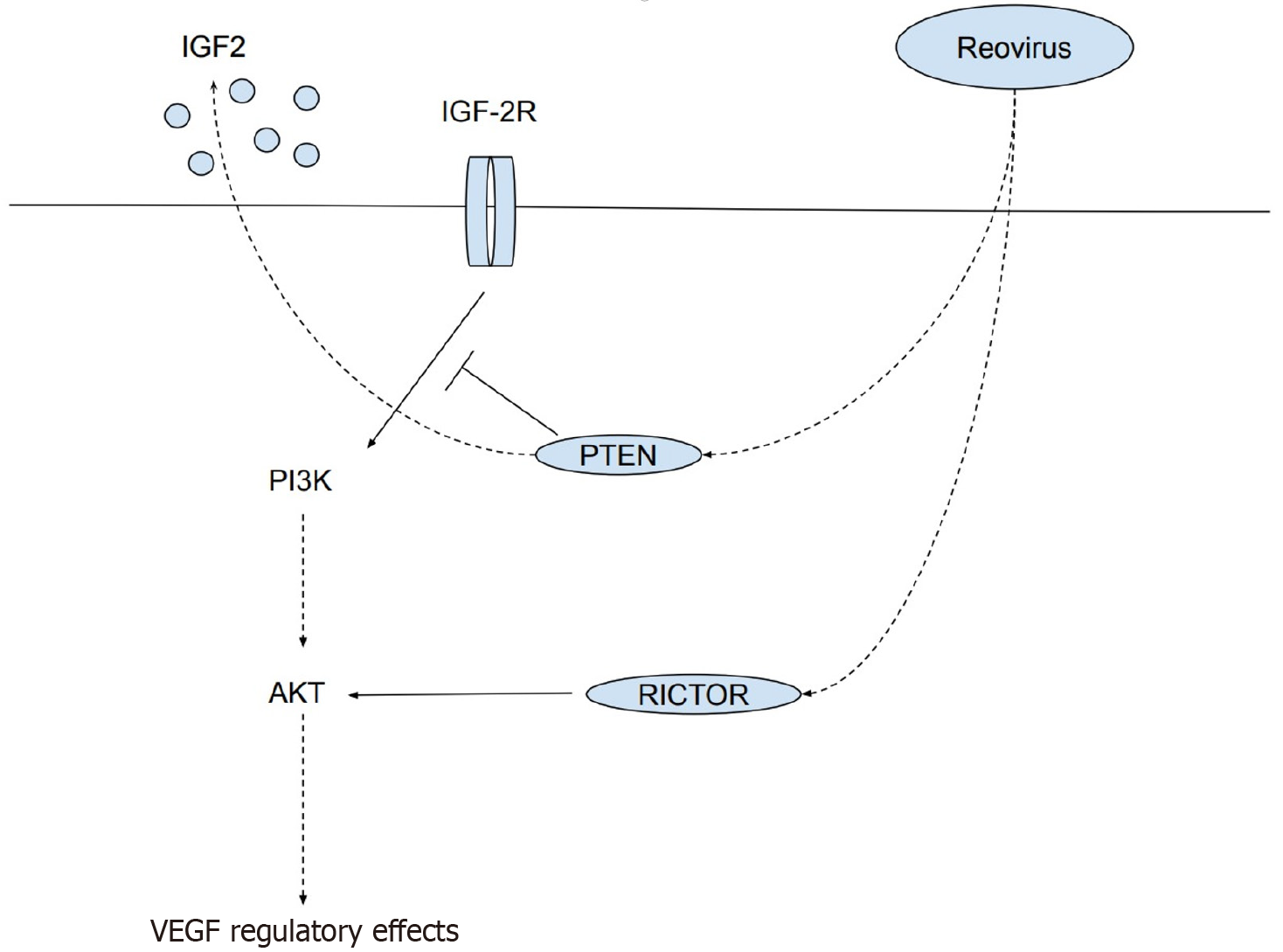

Significant alterations of three genes associated with the PI3K/AKT pathway, IGF2, PTENP1, and RICTOR are correlated with a reduction in the level of VEGF. Statistically significant reductions were observed for IGF2 expression on day 2 (Figure 2A) [0.78-fold change (22% decrease); P = 0.02]; and days 2 [0.88-fold change (12% decrease); P = 0.04] and 8 [0.86-fold change (14% decrease); P = 0.04] for RICTOR. A statistically significant increase was observed for PTENP1 on day 2 [1.57-fold change (57% increase); P = 0.02; Figure 2A]. Statistically significant decreases were observed for VEGF at 24 hours in Figure 2B [0.80-fold change (20% decrease); P = 0.0003], day 2 [0.64-fold change (36% decrease); P = 0.007], and day 3 [0.77-fold change (23% decrease); P = 0.002].

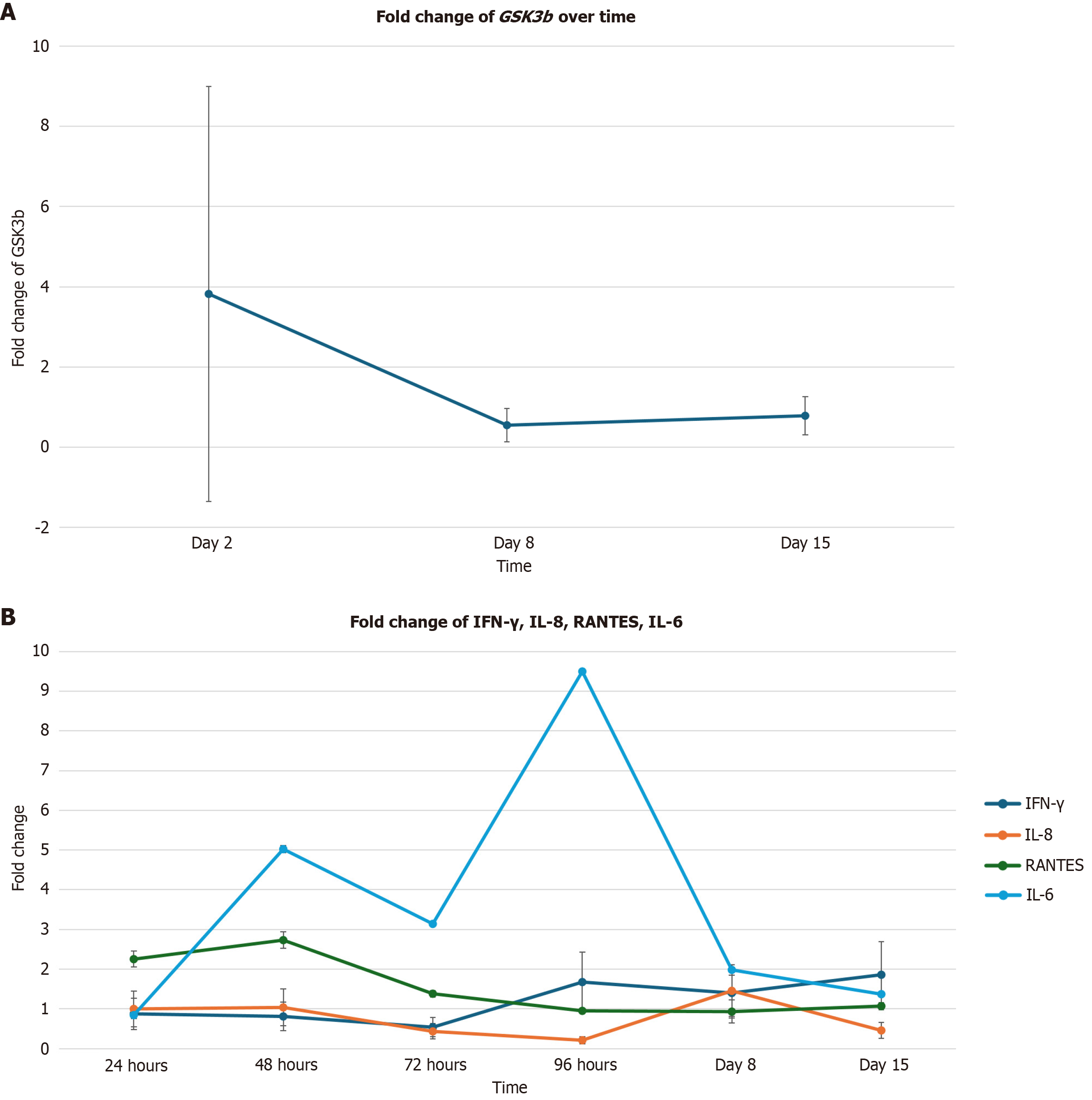

Expression of the GSK3β gene, which is associated with the PI3K/AKT pathways, was significantly upregulated on day 2 (Figure 3A) [3.82-fold change (282% increase); P = 0.03] and significantly downregulated on days 8 [0.55-fold change (55% decrease); P = 0.008] and 15 [0.78-fold change (22% decrease); P = 0.03].

The levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines RANTES and IL-8 were initially upregulated and then downregulated. A statistically significant increase in RANTES expression was observed on day 2 (Figure 3B) [2.73-fold change (173% increase); P = 0.04], followed by a significant decrease in expression on day 8 [0.93-fold change (7% decrease); P = 0.02]. Although IL-6 expression was significantly upregulated on day 8 [1.98-fold change (98% increase); P = 0.0001; Figure 3B] as compared to baseline, its expression showed a downward trend, beginning on day 2.

A statistically significant decrease in IFN-γ expression was observed on day 3 in Figure 3B [0.64-fold change (36% increase); P = 0.0001], followed by a significant increase in expression on day 15 [1.86-fold change (86% increase); P = 0.0004]. Additionally, statistically significant decreases in IL-8 expression were observed on days 3 [0.43-fold change (57% decrease); P = 0.02], 4 [0.21-fold change (79% decrease); P = 0.00003], and 15 [0.46-fold change (54% decrease); P = 0.03].

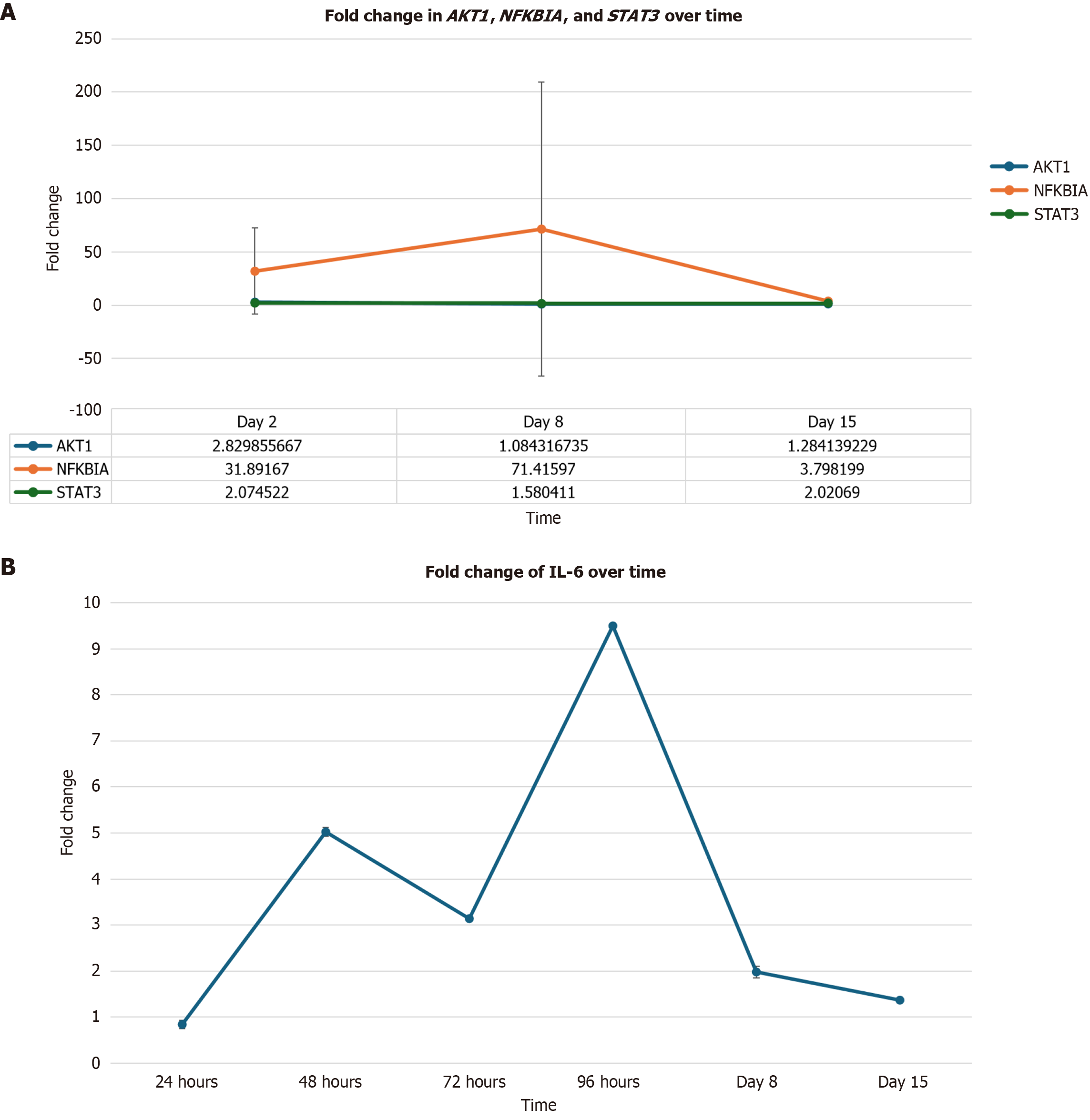

Statistically significant increases were observed in AKT1 on day 2 (Figure 4A) [2.83-fold change (183% increase); P = 0.004]; and in NFKBIA on days 2 [31.89-fold change (3.089% increase); P = 0.004] and 8 [71.42-fold change (7.042% increase); P = 0.03]. As previously mentioned, IL-6 expression was significantly upregulated on day 8 in Figure 4B [1.98-fold change (98% increase); P = 0.0001]. Additionally, statistically significant increases were observed in STAT3 on days 8 (Figure 4A) (1.58-fold change 9585 increase; P = 0.008) and 15 [2.02-fold change (102% increase); P = 0.05].

The objective of this research endeavor was to explore the effect of treatment with reovirus at the transcriptional level by examining the cytokine and gene expression levels select genes from 5 reovirus-treated mCRC patients. Significant alterations of 85 of 271 examined genes and 17 of 25 examined cytokines suggest that reovirus has a profound impact on the gene and cytokine expression of mCRC patients. Changes in the expression of genes linked to significantly altered cytokines are used to provide additional support for the validity of the cytokine expression findings, given the small sample size. These alterations demonstrate that reovirus triggers a complex intracellular signaling cascade, producing cytokines across multiple families, including pro-inflammatory interleukins, tumor necrosis factors, chemokines, antiviral interferons, and growth factors. The results of this study highlight the viral agent’s potential to promote an antitumor microenvironment and the complexity of the antitumor immune response.

Understanding the causality of association between cytokine protein levels and gene expression is critical for elucidating immune regulatory mechanisms. In datasets where cytokine concentrations are quantified via ELISA and gene expression are profiled through transcriptomic approaches (e.g., RNA-seq), observed associations may reflect underlying biological processes, but do not inherently imply causation.

Cytokine production is a multi-layered process influenced by transcriptional activation, mRNA stability, translational efficiency, and post-translational modifications. While transcriptomic data provide insights into the transcriptional landscape, ELISA captures the functional output at the protein level. Discrepancies between mRNA abundance and cytokine levels may arise due to regulatory mechanisms such as microRNA-mediated silencing, alternative splicing, or protein degradation pathways.

To infer causality, it is essential to apply statistical frameworks that go beyond correlation. Methods such as mediation analysis, Granger causality, or structural equation modeling can help determine whether gene expression changes precede and potentially drive cytokine production, or whether both are co-regulated by upstream signaling events (e.g., NF-κB or STAT pathways). Integrating time-series data, perturbation experiments, or causal inference models can further strengthen the evidence for directional relationships.

Ultimately, establishing causality requires a combination of computational modeling and experimental validation. This approach enables a more accurate interpretation of immune responses and supports the identification of key regulatory genes that may serve as therapeutic targets or biomarkers. In the current study with small sample size, it has been difficult to establish such correlation albeit the data looks convincing and provides a guidance to design future studies in a therapeutically meaningful way.

Significant alterations of three genes associated with the PI3K/AKT pathway, IGF2, PTENP1, and RICTOR are correlated with a reduction in the level of VEGF post reovirus administration. The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in known to regulate cellular survival over all proliferation. The aberrant activation of this pathway is typically associated with tumor progression and resistance to cancer therapies[9]. However, alterations of several genes associated with this pathway - PTENP1, IGF2, and RICTOR - are associated with reductions in the expression of VEGF. VEGF is a proinflammatory cytokine that contributes to several key aspects of tumorigenesis including stimulating angiogenesis and vascular permeability, and promoting growth, survival, migration, and invasion of cancer cells[10].

PTENP1 is a frequently inactivator tumor suppressor gene and a negative regulator of the PI3K/AKT cascade, which controls cell growth, proliferation, survival, and metabolism[11]. It appears that PTEN signaling down regulates IGF2 expression and signaling[12]. The IGF2 gene works as a satellite regulator of growth pathways in and the upregulation of this gene is associated with the promotion of cancer cell growth through several types of receptors[13]. It has been demonstrated that the blockage of IGF2 expression results in the down-regulation of VEGF, thereby inhibiting tumor growth and progression[12].

RICTOR is a critical molecule for mechanistic target of rapamycin 2 kinase activity and is involved in the tumorigenesis of a number of cancer cell types[10]. RICTOR is involved in tumor progression by regulating the tumoral microenvironment through either angiogenesis or stroma remodeling. RICTOR blockage in pancreatic tumors has been shown to significantly reduce VEGF expression[10].

The results of this experiment demonstrate a correlation between: (1) PTENP1 upregulation and IGF2 downregulation; (2) RICTOR downregulation; and (3) Reductions in VEGF expression across various time points. This correlation suggests that reovirus downregulates VEGF expression via alterations in the PI3K/AKT pathway (Figure 5).

Significant alterations in GSK3β expression are associated with significant alterations in IFN-γ, IL-8, RANTES, and IL-6 expression across various time points. GSK3β is a serine threonine kinase which is an emerging target for a number of malignancies, including pancreatic cancer, colon cancer, bladder cancer, kidney cancer, and melanoma[14]. GSK3β ac

The predominant role of IL-6 is to promote tumor growth and expression[16]. IL-8 expression promotes angiogenesis, the recruitment of immunosuppressive cells, and stimulates the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition[17]. RANTES is an important chemokine involved in the modulation of the TME and its activity is associated with angiogenesis, lymph genesis, and immune escape in colorectal cancer patients[18]. Furthermore, GSK3β also regulates other transcription factors involved in inflammation, such as IFN-γ[15]. Inhibition of GSK3β is associated with IFN-γ-induced STAT1 ac

GSK3β expression was significantly upregulated, then downregulated throughout the duration of this experiment. GSK3β upregulation and downregulation coincided with the upregulation and downregulation of IL-6, IL-8, and RANTES. Additionally, GSK3β upregulation and downregulation also coincided with the downregulation and upregulation of IFN-γ. The correlation between the alterations of GSK3β, IL-6, IL-8, and RANTES expression suggests that reo

Inhibitors of RANTES and IL-8 are currently being developed to treat a variety of malignancies, ranging from breast cancer to colorectal cancer[17,18]. IFN-γ is considered to play a major role in regulating antitumor immunity by in

Significant alterations of AKT1, NFKBIA, and IL-6 are associated with significant increases in STAT3 expression. STAT3 is frequently activated in malignant cells and plays a role in inducing the expression of many genes involved in tumorigenesis and inflammation. Aberrant expression of this gene in cancer cell results in the continuous transcription of cell growth factors and anti-apoptotic molecules[20]. These molecules play a crucial role in maintaining cell growth and survival, promoting tumor invasion, migration, metastasis, and angiogenesis when overexpressed[20].

AKT1, a gene that encodes for mitogen-activated survival factor, has been shown to increase the activity of NFKBIA. NFKBIA is a part of the NF-кB family and plays a role in mediating the expression of genes involved in inflammation, immune response, cell survival, and cancer[21]. NF-кB activation increases the expression of major inflammatory factors, such as IL-6[20]. Expression of this cytokine promotes tumor growth by activating STAT3 expression through tyrosine phosphorylation and the transcription of target genes vital to cancer formation[16].

Correlations between the upregulation of AKT1, NFKBIA, IL-6 and STAT3 expression throughout this experiment suggest that reovirus upregulates STAT3 expression via the NF-кB signaling pathway. STAT3 expression may either result in the activation or suppression of an inflammatory response depending on the physiological status of the cell, de

The limitations of this study include a small patient cohort (n = 5), reliance on peripheral blood samples, and the absence of long-term survival data. The small sample size limits the generalizability of the findings and contributes to large standard error of the mean values across the dataset, reducing the precision and reproducibility of the results. To partially circumvent the constraints of a small sample size, we examined expressions at both the transcriptional and translational levels. The transcriptomics of each patient was analyzed at three different time points, and changes in the expression of genes linked to significantly altered cytokines were used to provide additional support for the validity of the cytokine expression findings.

Peripheral blood samples may not accurately reflect the kinetics of genes and cytokine expression within the TME, as they are often influenced by systemic factors and comorbidities. Although tumor biopsies would have provided a more direct and precise assessment of the TME, they were not collected due to their invasive nature. It is common to use peripheral blood samples in mCRC studies because they are easier to obtain noninvasively than tumor biopsies. Additionally, the absence of long-term survival data prevents an evaluation of the sustained effects of reovirus on KRAS-mutant mCRC.

The findings of this study underscore the potential of reovirus to serve as both an immunomodulatory agent and a cytotoxic adjuvant to standard chemotherapy in patients with KRAS-mutant mCRC. Reovirus promotes an anti-tumor environment via the anti-angiogenic effects of decreased IL-8 and VEGF expression, encouraging further investigation of reovirus as a potential adjuvant to standard care. The viral agent has the potential to initiate an anti-tumor immune response through acute production of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, IFN-γ, and RANTES. To determine the efficacy of reovirus in promoting anti-tumor immunity, the immune landscape of KRAS-mutant mCRC in a large cohort of patients must be evaluated post-reovirus administration.

| 1. | Parakrama R, Fogel E, Chandy C, Augustine T, Coffey M, Tesfa L, Goel S, Maitra R. Immune characterization of metastatic colorectal cancer patients post reovirus administration. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Neugut AI, Lin A, Raab GT, Hillyer GC, Keller D, O'Neil DS, Accordino MK, Kiran RP, Wright J, Hershman DL. FOLFOX and FOLFIRI Use in Stage IV Colon Cancer: Analysis of SEER-Medicare Data. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2019;18:133-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yu IS, Cheung WY. Metastatic Colorectal Cancer in the Era of Personalized Medicine: A More Tailored Approach to Systemic Therapy. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;2018:9450754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Goel S, Ocean AJ, Parakrama RY, Ghalib MH, Chaudhary I, Shah U, Viswanathan S, Kharkwal H, Coffey M, Maitra R. Elucidation of Pelareorep Pharmacodynamics in A Phase I Trial in Patients with KRAS-Mutated Colorectal Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2020;19:1148-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Arrington AK, Heinrich EL, Lee W, Duldulao M, Patel S, Sanchez J, Garcia-Aguilar J, Kim J. Prognostic and predictive roles of KRAS mutation in colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:12153-12168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wu YY, Sun TK, Chen MS, Munir M, Liu HJ. Oncolytic viruses-modulated immunogenic cell death, apoptosis and autophagy linking to virotherapy and cancer immune response. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1142172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Maitra R, Ghalib MH, Goel S. Reovirus: a targeted therapeutic--progress and potential. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10:1514-1525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jiffry J, Thavornwatanayong T, Rao D, Fogel EJ, Saytoo D, Nahata R, Guzik H, Chaudhary I, Augustine T, Goel S, Maitra R. Oncolytic Reovirus (pelareorep) Induces Autophagy in KRAS-mutated Colorectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:865-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu P, Cheng H, Roberts TM, Zhao JJ. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:627-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2188] [Cited by in RCA: 2205] [Article Influence: 129.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Goel HL, Mercurio AM. VEGF targets the tumour cell. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:871-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 799] [Cited by in RCA: 996] [Article Influence: 76.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Luongo F, Colonna F, Calapà F, Vitale S, Fiori ME, De Maria R. PTEN Tumor-Suppressor: The Dam of Stemness in Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:1076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Livingstone C. IGF2 and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20:R321-R339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kasprzak A, Adamek A. Insulin-Like Growth Factor 2 (IGF2) Signaling in Colorectal Cancer-From Basic Research to Potential Clinical Applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dimou A, Syrigos KN. The Role of GSK3β in T Lymphocytes in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Beurel E. Regulation by glycogen synthase kinase-3 of inflammation and T cells in CNS diseases. Front Mol Neurosci. 2011;4:18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chonov DC, Ignatova MMK, Ananiev JR, Gulubova MV. IL-6 Activities in the Tumour Microenvironment. Part 1. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7:2391-2398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gonzalez-Aparicio M, Alfaro C. Implication of Interleukin Family in Cancer Pathogenesis and Treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mielcarska S, Kula A, Dawidowicz M, Kiczmer P, Chrabańska M, Rynkiewicz M, Wziątek-Kuczmik D, Świętochowska E, Waniczek D. Assessment of the RANTES Level Correlation and Selected Inflammatory and Pro-Angiogenic Molecules Evaluation of Their Influence on CRC Clinical Features: A Preliminary Observational Study. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58:203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zaidi MR. The Interferon-Gamma Paradox in Cancer. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2019;39:30-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tolomeo M, Cascio A. The Multifaced Role of STAT3 in Cancer and Its Implication for Anticancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 45.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Huang WC, Hung MC. Beyond NF-κB activation: nuclear functions of IκB kinase α. J Biomed Sci. 2013;20:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/