Published online Feb 24, 2026. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v17.i2.113674

Revised: October 24, 2025

Accepted: December 19, 2025

Published online: February 24, 2026

Processing time: 158 Days and 23.9 Hours

Digestive tract tumors represent a substantial global public health challenge, accounting for elevated morbidity and mortality rates. Perineural invasion (PNI), the spread of tumor cells along nerve fibers, has emerged as a key driver of aggressiveness and a poor prognosis. This study systematically reviews the complex, underexplored interplay between PNI and antitumor immunity in gastrointestinal cancers. By analyzing immune-related components (the prog

Core Tip: Digestive tract tumors remain a major global health burden with high morbidity and mortality. Perineural invasion (PNI), the infiltration of tumor cells along nerves, is a key determinant of tumor aggressiveness and poor outcome. This review systematically investigates the crosstalk between PNI and immune mechanisms in gastrointestinal cancers, with a focus on critical components, including the programmed cell ligand 1/programmed cell 1 axis, T cells, macrophages, and other immune checkpoints. It reveals mechanisms by which PNI reshapes the tumor immune microenvironment to promote metastasis, identify candidate immunotherapeutic targets, and provide a foundation for developing precision treatment strategies.

- Citation: Pang JY, Jin RY, Zhang HX, Zhang YH, Wei XY, Cao WB, Chen YX, Wang JL, Mo SJ. Perineural invasion in digestive tract tumors: Immune system interactions and therapeutic strategies. World J Clin Oncol 2026; 17(2): 113674

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v17/i2/113674.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v17.i2.113674

Digestive tract tumors, including gastric cancers (GC), colorectal cancers (CC), and esophageal cancers (EC), impose a substantial global health burden, causing more than 4 million deaths each year[1]. These malignancies often present with nonspecific early symptoms, leading to delayed diagnosis and high rates of morbidity and mortality. Advanced disease commonly displays aggressive features such as perineural invasion (PNI), a pathological hallmark linked to poor prognosis[2]. Patients with PNI-positive tumors have a two to threefold higher risk of local recurrence and distant metastasis compared with PNI-negative patients, highlighting its clinical relevance[3]. PNI, defined as tumor cell infiltration along nerve fibers often extending beyond the primary tumor bed[4], has been identified as an independent predictor of adverse outcomes in gastrointestinal cancers. For example, it is associated with lower 5-year survival in CC[5] and with increased lymphovascular invasion and peritoneal dissemination in GC. Thus, PNI represents not only a histopathological sign but also a driver of tumor aggressiveness and therapeutic resistance.

The initiation and progression of PNI are tightly regulated by the tumor microenvironment (TME), a complex milieu of immune cells, nerves, and stromal components that can either restrain or facilitate neural invasion[6]. Under homeostatic conditions, cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and natural killer (NK) cells exert antitumor effects that may limit PNI, but tumors frequently subvert these defenses by reshaping the TME toward immunosuppression[7], and dysregulation of the neuroendocrine-immune (NEI) axis, which normally maintains homeostasis, contributes to cancer progression, including PNI[8]. For example, in EC, aberrant NEI interactions within the TME drive PNI through neuroactive molecules: Nerve growth factor (NGF) both stimulates tumor invasive pathways and supports neural sprouting, enabling spread along nerve fibers[9]; concomitantly, immune-evasive mechanisms, such as programmed death 1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) mediated T cell exhaustion and expansion of regulatory T cells (Tregs), create an immune-tolerant niche that favors PNI. Neuro-immune crosstalk mediated by neurotrophic factors and neurotransmitters remodels the TME, enhancing tumor-nerve interactions and reducing immune surveillance. This review examines how tumors co-opt immune mechanisms to promote PNI, with a focus on digestive tract cancers, and discusses implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy.

PNI, a critical pathological feature of tumor progression linked to poor clinical prognosis, is primarily driven by tumor-induced immune dysregulation[10]. Tumors evade anti-tumor immune surveillance and reshape the local TME to establish an immune-tolerant niche around nerve fibers, thereby facilitating the invasion of tumor cells into the nerve perineurium[8]. This process involves the coordinated involvement of multiple immune cell subsets, with CD8+ T cells (the core anti-tumor effectors), Tregs (the key mediators of immune tolerance), and other cell types (e.g., macrophages, NK cells) playing distinct yet interconnected roles. Notably, the molecular mechanisms underlying immune-mediated PNI are most thoroughly characterized in gastrointestinal tumors[11].

CD8+ T cells, the primary anti-tumor effectors, are consistently targeted for impairment in gastrointestinal tumors to eliminate their ability to suppress PNI. In esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), tumor cells upregulate PD-L1 to bind PD-1 on CD8+ T cells, blocking cytotoxic signaling and abrogating their tumor-killing capacity; this dysfunction, paired with Treg-secreted interleukin-35 (IL-35) that further dampens CD8+ T cell activity, removes a critical barrier to PNI[12]. GC employs similar strategies, with norepinephrine (NE) released by sympathetic nerves (recruited via tumor-secreted NGF) expanding Tregs that secrete IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) factors that directly suppress CD8+ T cell function, while tumor-derived exosomes may also carry inhibitory molecules to reinforce this impairment[13]. In colorectal carcinoma (CRC), the E3 ubiquitin ligase F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 3 (FOXP3) indirectly weakens CD8+ T cell activity by reducing interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production from Th1 cells, limiting the pro-inflammatory signals that sustain CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity, allowing tumor cells to invade nerve tissue unimpeded[14].

Tregs act as central mediators of immune tolerance in gastrointestinal tumor PNI, with their recruitment and activation tailored to reinforce the perineural immunosuppressive niche. ESCC and CRC both utilize chemokine ligand (CCL) 22 secreted by tumor or stromal cells to specifically attract Tregs to the tumor-nerve interface; once localized, these Tregs secrete Treg-secreted IL-35, a potent immunosuppressive cytokine that suppresses not only CD8+ T cells but also other anti-tumor immune subsets[15,16]. GC further amplifies Treg function via NE, which upregulates FOXP3 (the master transcription factor for Tregs) to enhance their suppressive capacity, ensuring sustained immune tolerance around nerves. This Treg-driven suppression creates a protected microenvironment where tumor cells can proliferate and invade without immune interference[17].

M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophages (M2 TAMs) contribute uniquely to gastrointestinal tumor PNI by combining immune suppression with structural remodeling of the neural microenvironment. In ESCC, M2 TAMs secrete matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9, which degrades the perineural extracellular matrix (ECM), breaking down physical barriers like type IV collagen and enabling tumor cell access to nerve fibers. GC recruits M2 TAMs via CCL12, and these cells secrete MMP-7 (to further degrade neural ECM) and NGF (to induce a neurotropic phenotype in tumor cells, guiding their migration toward nerves)[18]. CRC leverages the CCL5-CCR5 signaling axis to recruit M2 TAMs, which mirror the gastric TAM phenotype by secreting NGF (for tumor cell neurotropism) and MMP-7 (for ECM degradation), while also contributing to immune suppression via IL-10 secretion[19].

NK cells, critical innate anti-tumor effectors, are functionally impaired in gastrointestinal tumors to further weaken immune surveillance against PNI. In CRC, FOXP3 drives ubiquitination-dependent degradation of key signaling molecules, reducing IFN-γ production by NK cells, depriving the TME of a cytokine that not only enhances CD8+ T cell function but also directly inhibits tumor cell proliferation[20]. GC may similarly dampen NK cell activity through Treg-secreted TGF-β, which downregulates NK cell cytotoxic receptors, limiting their ability to target tumor cells invading nerve fibers[21].

Collectively, in EC, GC, and CC, the coordinated dysfunction of immune cells-impaired CD8+ T cells, enriched and activated Tregs, M2-polarized TAMs, and dysfunctional NK cells, creates a robust immune, tolerant niche around nerve fibers, while TAM-mediated ECM degradation removes physical barriers to invasion. This integrated immune dysregulation directly drives PNI, a process tightly linked to poor clinical outcomes in these gastrointestinal malignancies.

Immune checkpoint pathways and inflammatory programs are not isolated regulators of the TME; their coordinated crosstalk plays a pivotal role in shaping tumor susceptibility to PNI across cancer types[10]. Inflammatory processes disrupt tissue and neural homeostasis while boosting tumor invasiveness, laying a “pathological groundwork” for PNI initiation, whereas immune checkpoints act as an “immune evasion shield” to help tumor cells escape anti-tumor sur

In these gastrointestinal malignancies, the loop operates with distinct molecular signatures yet shared pro-PNI effects. In EC, linked to chronic irritation[24], tumor/stromal cells secrete IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor alpha to recruit neutrophils (releasing NETs/proteases to degrade perineural matrix) and macrophages (secreting reactive oxygen species to damage nerves); concurrently, cancer cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells upregulate PD-L1, which binds PD-1 on CD8+ T cells to induce exhaustion and prevent clearance of nerve-invading tumors, with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade plus anti-inflammatory therapy reducing neural invasion in preclinical models[25,26]. In GC, tumor-secreted tumor necrosis factor alpha/IL-6 initiates neuroinflammation, recruiting macrophages (producing reactive oxygen species/proteases) and triggering sensory nerves to release substance P (amplifying inflammation/tumor motility); PD-L1 upregulation by cancer cells/myeloid-derived suppressor cells further induces CD8+ T cell exhaustion, and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade mitigates neural invasion[27]. In CRC (often linked to chronic colitis/microbial dysbiosis), tumor cells downregulate CXCL10 (limiting effector T cell recruitment) and secrete CCL2 (attracting Tregs/M2 macrophages)[28]; inflammatory cues induce CTLA-4 on Tregs, which binds CD80/CD86 to suppress T cell activation, creating a TME with reduced lymphocytic infiltration that favors nerve invasion[29].

Across diverse tumor types, the crosstalk between neurotransmitters and the immune system, along with immune-related molecular signaling, forms a core regulatory network driving PNI, a process where tumor cells infiltrate nerve fibers and worsen prognosis[30]. This mechanism is broadly observed: For example, some tumors exploit neurotransmitters like acetylcholine (ACh) or NE in the TME to reprogram immune responses, such as impairing CD8+ T cell recruitment or expanding Tregs, while shared molecular pathways [e.g., agrin (AGRN)/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt), Notch/Wnt] further reinforce immune suppression and neural barrier disruption to support PNI. Though this neuro-immune regulatory framework operates across tumors like breast cancer or non-small cell lung cancer, it is particularly well-characterized, clinically relevant, and functionally prominent in gastrointestinal cancers[31].

In ESCC, a key gastrointestinal malignancy, tumor cells drive ACh accumulation in peritumoral and perineural regions via two complementary pathways specific to gastrointestinal tumor models. Activated α7 nicotinic Ach receptor on CD8+ T cells impairs their migration to perineural areas, while engagement of M3 muscarinic receptors on naive T cells promotes Th2 differentiation[32]. Th2-derived IL-4/IL-13 then dualizes to suppress CD8+ T cell activity and upregulate stromal MMPs, enzymes that break down neural barriers, accelerating PNI progression[33].

GC further leverages this neuro-immune axis to facilitate neural invasion. Tumor cells secrete NGF to recruit sympathetic nerves into the TME, which release NE; they also downregulate monoamine oxidase, the primary enzyme for NE degradation, to boost local NE accumulation. Elevated NE expands Tregs via FOXP3 upregulation, creating an immune-tolerant perineural niche[33]. Concurrently, GC cells secrete the chemokine CCL12 to attract neural precursor cells to perineural regions and secrete Wnt family member 3a, a ligand that induces NPC differentiation into Schwann-like cells capable of producing NGF and brain-derived neurotrophic factor[34]. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor then signals through tropomyosin related kinase B on CD4+ T cells, skewing their differentiation toward Th2 cells and reducing IFN-γ production, further weakening anti-tumor immunity and supporting PNI[35].

CC exhibits distinct molecular drivers of PNI within this neuro-immune framework, with prominent overexpression of AGRN in PNI-positive cases[36]. AGRN increases MMP-2/9 expression to disrupt neural barriers and activates PI3K/Akt signaling, promoting the polarization of M2 TAMs; these M2 TAMs secrete IL-10 and TGF-β to suppress anti-tumor immunity and recruit Tregs. AGRN also stimulates Schwann cells to secrete NGF, which activates NGF/TrkA signaling in tumor cells to enhance their motility and upregulate PD-L1 dampening T cell-mediated tumor clearance. Additionally, crosstalk between Notch/Wnt and neurotrophic pathways reinforces immune suppression: Notch activation upregulates p75NTR on Tregs, increasing their responsiveness to NGF, while Wnt/β-catenin signaling in fibroblasts induces IL-6, which synergizes with NGF to promote M2 TAM polarization. This feed-forward loop sustains neural remodeling and immune tolerance, driving PNI in CC[37].

In gastrointestinal cancers, the integration of neurotransmitter-immune crosstalk (such as the ACh/α7 nicotinic Ach receptor axis and NE/Treg interactions) and immune-related molecular signaling pathways (e.g., AGRN/PI3K/Akt and Notch/Wnt crosstalk) forms a robust regulatory network that drives PNI[38]. This underscores the therapeutic potential of targeting this regulatory axis; for instance, through inhibiting AGRN, blocking Notch/Wnt crosstalk, or disrupting neurotrophic-immune signaling to reactivate anti-tumor immunity and hinder PNI progression in these clinically significant malignancies.

PNI, a key pathological hallmark linked to poor prognosis in gastrointestinal tumors (EC, GC, and CC), is closely regulated by the immune system. The interplay between immune components and PNI progression in these three malignancies shares core regulatory patterns, while also exhibiting tumor-specific differences. When it comes to the similarities in immune regulation underlying PNI, including the consistent roles of immune cells, immune checkpoints, and immune-related pathways/mediators across EC, GC, and CRC, detailed elaboration and specific breakdowns are provided in the table below. These similarities form a unified framework of immune dysfunction that facilitates PNI in all three digestive tract cancers. As for the differences in immune system function underlying PNI across EC, GC, and CRC, these will be discussed in detail in the subsequent sections of the paper, and their key features will also be presented in a comparative manner in the following figure for clearer visualization.

Immune cell dysfunction is a hallmark of PNI in digestive tract tumors, but the specific patterns and consequences vary by tumor type. For instance, in EC, CD8+ cytotoxicity is suppressed by PD-L1 upregulation and other immunosuppressive mediators, facilitating neural spread[39]; in GC, PD-L1 and broader microenvironmental suppression blunt CD8+ activity, with the balance between stimulatory and inhibitory signals determining PNI extent. And in CRC, CD8+ dysfunction is driven by PD-1/PD-L1 signaling and Notch-associated microenvironmental remodeling; both infiltration and functional status of CD8+ cells are key prognostic indicators for PNI in CRC. The patterns of innate and other lymphoid populations also differ by tumor types. In EC, NK cell activity is often impaired, and macrophages skew toward protumor phenotypes that degrade perineural matrices[40]. In GC, reductions in B-cell antibody production, NK cytotoxicity, and dendritic cell antigen-presenting capacity have been reported. In CRC, macrophages exhibit context-dependent dual roles, supporting immunity in some settings and promoting invasion in others, while NK dysfunction is frequent[41].

Immune-checkpoint dysregulation is a shared mechanism of immune evasion in PNI, but checkpoint dominance and interactions vary among types of digestive tract tumors. For example, PD-L1 overexpression is common to EC, GC and CRC. In EC, PD-L1 binding to PD-1 on T cells suppresses T-cell activation and correlates with more extensive PNI and worse prognosis[42,43]; in GC, IFN-γ from CD8+ cells can paradoxically upregulate PD-L1 on tumor cells, enabling immune escape during nerve invasion[44]; in CRC, elevated PD-L1 on tumor and immune cells is likewise associated with extensive PNI and poor outcomes[45]. Other checkpoints also show tumor-specific prominence: TIM-3, linked to T-cell exhaustion, is particularly relevant in EC and is a potential therapeutic target to restore antitumor immunity; CTLA-4 contributes to T-cell suppression in GC and represents a possible intervention to counter PNI; in CRC, lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3) acts synergistically with PD-1 to inhibit T-cell responses, and LAG-3 blockade (especially combined with other checkpoint inhibitors) holds promise for improving PNI-associated outcomes[46].

Distinct signaling pathways and chemokines shape PNI in a tumor-specific manner, also found in digestive tract tumors. In EC, TGF-β suppresses antitumor immunity, modulates immune-cell phenotypes, and promotes invasive behavior along nerves, while CCL2 recruits macrophages and inflammatory cells to establish a pro-invasive perineural niche[47]. In GC, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 contributes to immune evasion by regulating PD-L1 expression and immune-cell recruitment, and Hedgehog signaling in cancer stem cells promotes tumor-nerve crosstalk that drives nerve invasion[47]. In CRC, Notch signaling sustains cancer stem cells, upregulates PD-L1, and reinforces tumor-nerve interactions, whereas the IL-6/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 axis sculpts an immunosuppressive TME by modulating PD-L1 expression and immune-cell function, both pathways cooperating to enable nerve-invasive growth[48]. Collectively, these differences highlight tumor-specific immune landscapes that determine how immune dysfunction contributes to PNI, and they underscore the need for tailored immunotherapeutic strategies for EC, GC, and CRC. A summary of the immune mechanisms driving PNI in digestive tract tumors is presented in Table 1[49-63].

| Molecules | Immune role | Similar role in EC, GC, and CRC with PNI | Different roles in EC, GC, and CRC with PNI | |

| Immune cells | CD8+ T cells | Recognize and kill tumor cells | Act as key immune regulatory cells in the PNI process; the number of infiltrating cells and their functional status are directly associated with patient prognosis; when functioning normally, they can inhibit the perineural invasive ability of tumor cells; when functionally impaired, they promote the occurrence of PNI | EC: Their antitumor function is significantly suppressed by PD-L1 in the tumor microenvironment and other immunosuppressive factors, increasing the risk of PNI; GC: Their function is impaired due to the PD-L1-mediated immune checkpoint pathway and factors such as hypoxia and lactic acid accumulation in the tumor microenvironment, failing to effectively prevent tumor perineural invasion; CRC: Dysfunction occurs due to abnormal activation of the PD-1/Notch signaling pathway; the density of infiltration and functional status can serve as important indicators for predicting the occurrence of PNI[54] |

| Tregs | Express FOXP3, exert immunosuppressive effects, suppress effector T-cell activity | Promote immune escape, alter frequency/function related to PNI[49,50] | Not mentioned | |

| B cells | Antitumor immune response by producing antibodies | Mediate the PNI process through antibody responses; for example, abnormal antibody secretion may affect the integrity of perineural tissues or promote the adhesion of tumor cells to nerves; interact with other immune cells in the tumor microenvironment to jointly regulate the perineural invasive behavior of tumor cells[51,52] | GC: The ability to produce antibodies is reduced, leading to weakened humoral immune surveillance against tumor cells and increased susceptibility to PNI; EC/CRC: No specific differential roles related to PNI mentioned | |

| NK cells | Directly kill tumor cells | Provide cytotoxicity against tumor cells; when their function is impaired, the ability to clear tumor cells is reduced, which facilitates tumor cells to invade nerves and promotes PNI; the functional status of NK cells in the tumor microenvironment is an important factor affecting the occurrence of PNI[51,52] | EC: The activity of NK cells is significantly impaired and their killing effect on tumor cells is weakened, which is conducive to the perineural invasion of tumor cells[55]; GC: The cytotoxicity of NK cells is reduced, making it difficult to effectively inhibit the growth and nerve invasion of tumor cells; CRC: Dysfunction of NK cells is frequent, and the abnormal function is closely related to the high incidence of PNI[56] | |

| DCs | Antigen presentation and T-cell activation | Play a role in T-cell priming in the PNI process; when DCs function normally, they can effectively activate T cells to inhibit tumor nerve invasion; dysfunction of DCs leads to insufficient activation of the adaptive immune response, creating conditions for tumor cells to invade nerves and promoting PNI[51,52] | GC: The antigen-presenting capacity of DCs is reduced, resulting in weakened activation of T cells and inability to form an effective antitumor immune response, thereby promoting PNI; EC/CRC: Not mentioned | |

| Macrophages | Exhibit dual functional phenotypes (antitumor M1 vs protumor M2) in the TME; associated with PNI | Assist in tumor nerve infiltration, mainly through the M2 protumor phenotype; M2 macrophages can secrete factors that promote tumor cell invasion and damage perineural tissues, thereby facilitating PNI; the polarization direction of macrophages in the TME affects the progression speed of PNI[51,52] | EC: Macrophages tend to exhibit protumor phenotypes; they can secrete enzymes (e.g., matrix metalloproteinases) to degrade perineural matrices, providing channels for tumor cells to invade nerves; CRC: Macrophages play context-dependent dual roles; in some microenvironments, they support the antitumor immune response to inhibit PNI, while in other contexts, they promote tumor cell invasion to accelerate PNI; GC: No specific differential roles related to PNI mentioned[56] | |

| Immune checkpoints | PD-1/PD-L1 axis | Tumor immune escape, suppresses T cells | Promotes PNI; poor PNI prognosis[53,55] | EC: Binds PD-1 to suppress T cells (correlates with extensive PNI)[57,58]; GC: Upregulated by CD8+ cell-derived IFN-γ (enables immune escape)[59]; CRC: Elevated on tumor/immune cells (associates with extensive PNI)[60] |

| PD-L1 | Binds to PD-1 on T cells inhibiting T-cell activity helping tumor cells evade immune attack | Inhibits T-cell activation, weakening the body’s ability to clear tumor cells, thereby creating favorable conditions for tumor cells to invade nerves and promoting PNI[54] | GC: Contributes to T-cell suppression; the high expression of PD-L1 on tumor cells significantly inhibits the function of infiltrating T cells in the TME, promoting PNI; EC/CRC: No specific differential roles related to PNI mentioned[61] | |

| PD-1 | Affects T-cell function, decreased immune surveillance | Synergizes with PD-1 to enhance immunosuppression, worsen PNI[54] | EC: Particularly relevant (T-cell exhaustion, potential therapeutic target)[61]; GC/CRC: No prominent role noted | |

| CTLA-4 | Reduces antitumor immune response efficiency, a different mechanism from PD-1/PD-L1 axis | Collaborates with other immune checkpoints (e.g., PD-1/PD-L1) to suppress T-cell function; the combined inhibitory effect further weakens the antitumor immune response, promoting the occurrence of PNI[54] | CRC: Synergizes with PD-1; the combined blockade of CTLA-4 and PD-1 can more effectively restore T-cell function, improve the antitumor immune response, and thus improve the prognosis of patients with PNI[61]; EC/GC: Not mentioned | |

| TIM-3 | An immunosuppressive molecule affects T-cell function | Aids in T-cell exhaustion and tumor immune escape; the activation of TIM-3 leads to the loss of T-cell immune function, making it easier for tumor cells to invade nerves and promoting PNI[53,54] | EC: Promotes the traits of CSCs (e.g., self-renewal, invasiveness) and enhances the invasive ability of tumor cells; indirectly aids the perineural invasion of tumor cells by regulating CSC function and immune cell activity[61]; GC/CRC: Not mentioned | |

| LAG-3 | Together with CTLA-4 and TIM-3, it inhibits tumor-reactive T-cell stimulation and proliferation, and T-cell dysfunction | Cooperates with PD-1 to inhibit T cells, aids PNI[53,54] | CRC: Synergizes with PD-1 to suppress T cells; combined blocking of LAG-3 and PD-1 shows promise for improving PNI outcomes[60]; EC/GC: Synergistic effect with PD-1 is less prominent in PNI | |

| Immune-related factors | IFN-γ | Dual-role: Activates immune cells and enhances immune surveillance; induces tumor cells to express PD-L1, disrupting immune balance | Affects the balance of PNI; on one hand, it enhances immune surveillance to inhibit tumor nerve invasion; on the other hand, it promotes tumor immune escape by inducing PD-L1 expression, thereby facilitating PNI; the final effect depends on the relative intensity of the two roles[58,59] | GC: Upregulates the expression of PD-L1 on tumor cells; the high expression of PD-L1 enables tumor cells to evade the attack of T cells, promoting the perineural invasion of tumor cells[59]; EC/CRC: No specific role noted |

| TGF-β | Modulates TME immunosuppression, regulates immune cell function | Exerts protumor and immunosuppressive effects; disrupts the immune homeostasis in the TME, weakens the antitumor immune response, and creates favorable conditions for tumor cells to invade nerves, thereby promoting PNI[56,57] | EC: Suppresses immunity, modulates immune-cell phenotypes, promotes nerve invasion; CRC: Role more prominent vs EC/GC; it can strongly regulate the TME and tumor cell behavior to accelerate PNI[50,62] | |

| Notch signaling | CSCs’ differentiation and self-renewal affect immune cell function | Promotes the traits of CSCs (e.g., self-renewal, invasiveness) and enhances the invasive ability of tumor cells; indirectly aids the perineural invasion of tumor cells by regulating CSC function and immune cell activity[61,62] | CRC: Promotes the traits of CSCs (e.g., self-renewal, invasiveness) and enhances the invasive ability of tumor cells; indirectly aids the perineural invasion of tumor cells by regulating CSC function and immune cell activity[63]; EC/GC: Not mentioned | |

| Hedgehog signaling | Active in CD133-positive CSCs | Regulates the crosstalk between tumor cells and nerves; promotes the perineural spread of tumor cells by mediating the communication between tumor cells and nerve cells[56,57] | GC: Drives the crosstalk between tumor cells and nerves; directly promotes the perineural invasion of tumor cells by regulating the expression of factors related to nerve invasion[61]; CRC: Is active in CD133+ CSCs, but the crosstalk between tumor cells and nerves mediated by this pathway is weak, and its role in PNI is less prominent[52]; EC: No specific tumor-nerve crosstalk role in PNI | |

| VCAM1 | Related to PD-L1 expression, tumor immune escape | Regulates the expression of PD-L1 and the recruitment of immune cells; promotes tumor immune escape, thereby creating conditions for tumor cells to invade nerves and facilitating PNI | GC: Contributes to tumor immune evasion; regulates the expression of PD-L1 on tumor cells and the recruitment of immunosuppressive cells (e.g., Tregs) in the TME, thereby promoting PNI[62]; EC/CRC: Not mentioned | |

| CCL2 | Mediates inflammatory cell recruitment, attracts macrophages | Recruit macrophages and inflammatory cells to the perineural area; damages perineural tissues by regulating the inflammatory response; drives the perineural invasion of tumor cells[63] | EC: Establishes a pro-invasive perineural niche; recruit macrophages and other inflammatory cells to the perineural microenvironment, creating a microenvironment conducive to tumor nerve invasion[62]; GC/CRC: Not mentioned | |

| IL6/STAT3 signaling pathway | Related to VCAM1 and PD-L1 expression, it disrupts the immune balance | Regulates the recruitment of immune cells and the expression of PD-L1; promotes tumor immune escape, thereby facilitating the perineural invasion of tumor cells and promoting PNI | CRC: Sculpts the immunosuppressive TME; modulates the expression of PD-L1 on tumor cells and the function of immune cells (e.g., inhibits the cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells); cooperates with other pathways to promote the perineural invasion of tumor cells[63]; EC/GC: Not mentioned | |

PNI, a pathological process characterized by tumor cell infiltration into nerve bundles or perineural spaces, exhibits distinct impacts on patient prognosis and underlying mechanisms across different digestive tract tumors. Its core clinical significance lies in serving as a reliable indicator for evaluating disease progression, recurrence risk, and long-term survival outcomes.

CRC: PNI has been consistently identified as an independent poor prognostic factor in CRC. Clinical evidence de

GC: In GC, PNI also functions as an independent prognostic indicator, with its prognostic relevance being more pronounced in advanced-stage disease. Pathological and clinical correlations reveal that PNI+ in GC is closely associated with deeper tumor invasion (e.g., T3/T4 stages according to the TNM staging system), lymph node metastasis, and an elevated risk of peritoneal recurrence. For patients who have undergone radical gastrectomy (the primary curative treatment for resectable GC), PNI positivity is consistently linked to shorter OS, underscoring its role in stratifying high-risk GC populations postoperatively[65].

EC: The incidence of PNI in EC varies between 15% and 40%, with no significant difference observed between the two major histological subtypes: ESCC and esophageal adenocarcinoma. PNI in EC is strongly correlated with local tumor progression and lymph node metastasis. Clinically, PNI+ EC patients face a higher risk of local recurrence following definitive treatment (e.g., surgical resection or concurrent chemoradiotherapy), and their long-term survival (including 3-year and 5-year OS) is significantly lower than that of PNI- EC patients. This suggests that PNI status could be integrated into EC staging systems to refine prognostic stratification[66].

Despite growing evidence supporting PNI’s prognostic value in digestive tract tumors, academic inconsistencies persist, driven by three key factors: First, no global unified pathological definition or standardized detection method for PNI exists variations in experimental protocols (e.g., immunohistochemical staining, microscopic criteria for “nerve invasion”, and nerve assessment scope) cause significant differences in PNI incidence across studies, reducing result comparability. Second, most existing studies are single-center, small-sample, or single-tumor-focused; large-scale, multi-center prospective studies covering multiple digestive tract malignancies (to address inter-tumor heterogeneity) are scarce, limiting conclusion generalizability. Third, PNI often coexists with other poor prognostic factors (e.g., lymph node metastasis, vascular invasion, and advanced TNM stage), and insufficient adjustment for these confounders in some studies hinders isolating/validating PNI’s independent prognostic value, leading to conflicting interpretations of its clinical significance.

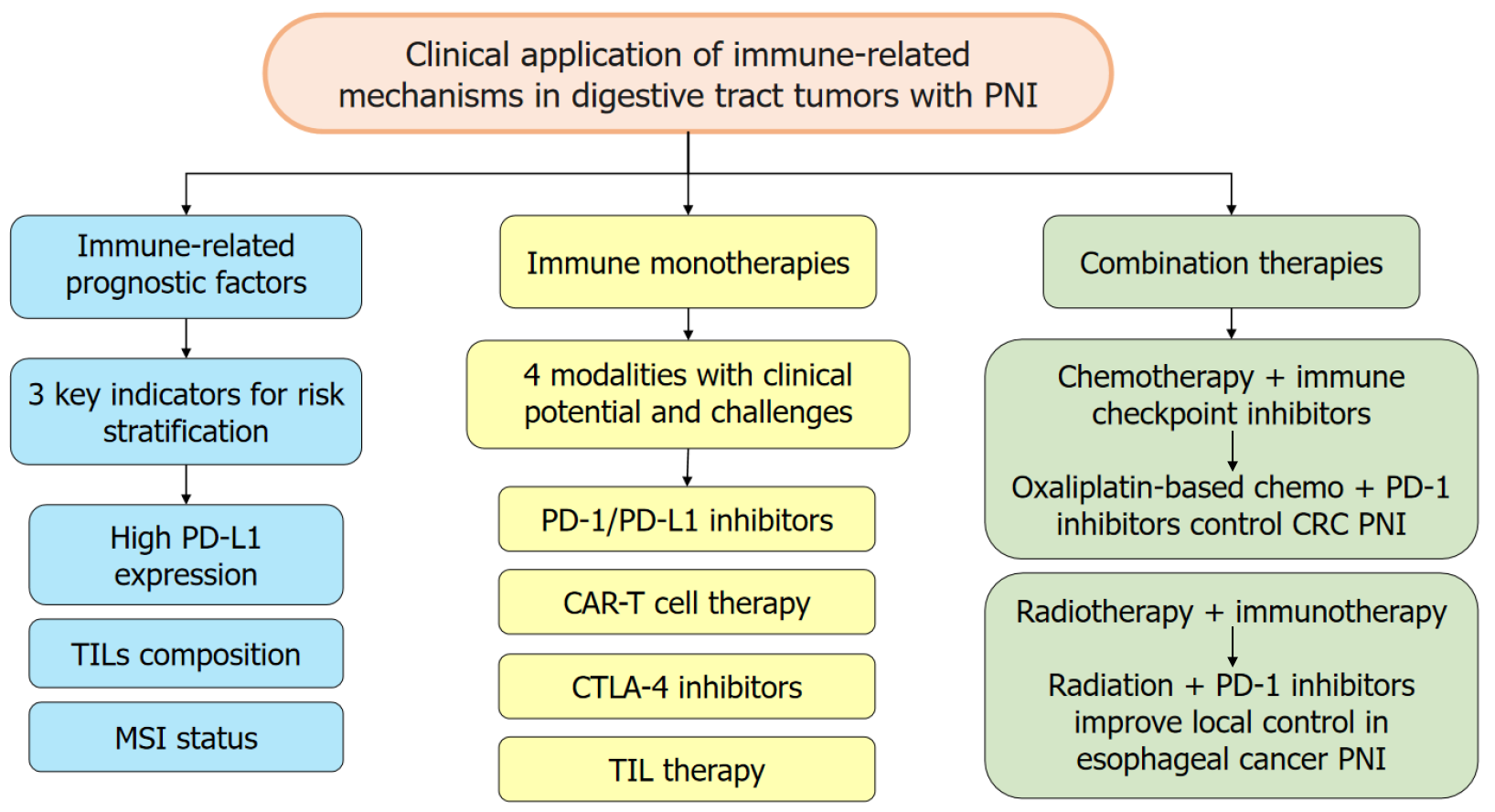

Immune factors, such as PDL1 expression, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) density and composition (CD8+ vs FOXP3+), microsatellite instability (MSI) status, serve as prognostic biomarkers in tumors with PNI, helping to stratify patients by recurrence risk and OS. In digestive tract tumors with PNI, high PD-L1 expression on tumor and immune cells correlates with increased nerve invasion and worse prognosis. PD-L1 binding to PD-1 suppresses T cell-mediated immunity and facilitates tumor spread along nerves. PD-L1 assessment can aid patient stratification; for example, PNI+ CC patients with high PD-L1 tend to have shorter diseasefree and OS[67]. However, PD-L1 status depends on assay platform and cutoffs, so standardization is required for reliable prognostication[68].

The density and composition of TILs are prognostically informative. A high density of CD8+ T cell-dominant infiltrates generally indicates a more active antitumor response and better prognosis[67]. By contrast, enrichment of FOXP3+ Tregs reflects an immunosuppressive microenvironment and poorer outcomes[69]. Pathological evaluation of TILs quantity and phenotype at resection can provide useful prognostic information and help guide adjuvant therapy decisions. MSI status is relevant to the immune response in digestive tract tumors with PNI[70]. MSI-high tumors carry a higher mutation burden and generate more neoantigens, increasing tumor immunogenicity. In PNI+ CRC, MSI-high status predicts greater responsiveness to immunotherapy and often a more favorable prognosis compared with microsatellite-stable tumors. MSI testing is therefore important for prognostic assessment and therapeutic planning in PNI+ CRC[70].

Immunotherapy harnesses and enhances the patient’s immune system to recognize and eliminate cancer cells, using approaches such as immune checkpoint blockade (e.g., anti-PD-1/PD-L1) and adoptive approaches [chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T), TILs]. By restoring or redirecting anti-tumor immunity, immunotherapy can reduce PNI and improve outcomes across digestive tract tumors. By blocking PD-1/PD-L1 interactions, these agents can reinvigorate T cells and restore antitumor activity within the perineural niche, overcoming tumor immune-evasion mechanisms[71]. Clinical trials show benefit in subsets of patients with digestive-tract tumors and PNI. For example, some advanced GC patients experienced tumor reduction and improved survival with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade[72,73]. CTLA-4 blockade enhances T-cell priming and activation and may augment antitumor immunity in PNI. Although less studied specifically in PNI-positive digestive cancers, CTLA-4 inhibitors have shown synergistic effects with PD-1 blockade in preclinical models of PNI (e.g., pancreatic cancer), improving control of tumor growth and nerve invasion[74]. TIM-3 is broadly expressed in EC, GC, and CRC and is linked to T-cell exhaustion, but its inhibitors are currently in early clinical development[75-78]. LAG-3 acts synergistically with CTLA-4 and TIM-3 to suppress tumor-reactive T cells, and co-expression with PD-1 marks profound T-cell dysfunction in these three cancers; LAG-3 blockade, especially in com

Currently, CAR-T cell therapy for digestive-tract tumors with PNI remains at an early developmental stage[81]. Pre

Chemotherapy can directly kill tumor cells involved in PNI and reduce overall tumor burden. It also induces immu

Radiotherapy damages tumor cells implicated in PNI and promotes the release of damage-associated molecular patterns and tumor antigens, which can activate innate and adaptive immunity[85]. When paired with immunotherapy, radiotherapy can convert the TME into a more immunogenic state, enhancing local and systemic antitumor effects and helping to eradicate radio-resistant cells associated with PNI. In EC with PNI, combined radiotherapy and immune checkpoint blockade have demonstrated potential to improve local control and reduce distant metastasis in some studies[86]. Nonetheless, the optimal radiation dose, fractionation, and timing relative to immunotherapy must be further optimized to maximize benefit and minimize toxicity. A schematic summary of the clinical application of immune-related mechanisms in digestive tract tumors with PNI is shown in Figure 1.

From a system and ecological viewpoint, digestive tract cancer (including PNI) is not an isolated cellular abnormality but a disruption of the “tumor ecosystem”, a dynamic network of tumor cells, immune cells, nerves, stromal cells, and ECM, interacting with the host’s systemic physiology. The tumor ecosystem constitutes a sophisticated hierarchical network of interactions that operates across distinct spatial scales, with the microscale perineural niche and macroscale tumor-host system functioning in concert to modulate tumor progression, particularly PNI. At the microscale, the perineural niche functions as a “specialized microecosystem” where tumor cells, nerves, and immune cells engage in reciprocal crosstalk. For example, tumor-secreted NGF promotes neural sprouting, while nerves release NE to reshape immune cell phenotypes (e.g., Treg expansion). Immune cells (e.g., M2 TAMs) further modify the niche by degrading ECM and secreting immunosuppressive cytokines, creating a “permissive habitat” for PNI.

This microscale regulatory network is not isolated but tightly integrated into the macroscale tumor-host system, primarily through the host’s NEI axis, which acts as a systemic mediator linking local niche dynamics to whole-organism physiology. Chronic inflammation (e.g., from gastric Helicobacter pylori infection or colitis in CRC) disrupts NEI homeostasis, driving systemic immune suppression. For instance, elevated systemic NE levels (from stress or tumor-induced sympathetic activation) enhance Treg infiltration into the perineural niche, promoting PNI across digestive tract tumors[87].

The progression of PNI, a critical pathological process in tumor progression, is profoundly shaped by core ecological principles that govern interactions between organisms and their environments. A fundamental ecological principle underlying PNI is niche construction, wherein tumor cells actively remodel the perineural microenvironment to form a supportive niche conducive to their survival and invasion, mirroring the way organisms in natural ecosystems alter their habitats to enhance adaptive fitness. Tumor cells execute this niche construction by secreting a repertoire of bioactive factors, such as NGF and CCL22, which serve to recruit key supportive cellular components including nerves, Tregs, and M2-polarized TAMs. Concurrently, these tumor-associated cells modify the ECM to further optimize the niche; for instance, in ESCC, M2 TAMs secrete MMP-9, which degrades type IV collagen in the perineural ECM to create physical channels that facilitate tumor cell invasion, an adaptation analogous to how organisms in natural ecosystems modify their habitats to enable movement and expansion.

Species competition and coexistence, another pivotal ecological principle, regulates the immunological balance at the perineural interface and thereby drives PNI progression. Within the tumor-perineural ecosystem, antitumor effector cells (such as CD8+ T cells and NK cells) and immunosuppressive cells (including Tregs and M2 TAMs) engage in intense competition for limited resources, encompassing cytokines, growth factors, and spatial niches. Tumor cells act as key modulators of this competitive balance by upregulating immune checkpoint molecules (e.g., PD-L1) and secreting immunosuppressive cytokines such as TGF-β. These strategies tip the competitive scales in favor of immunosuppressive cells, enabling them to outcompete and functionally suppress antitumor effector cell subsets. The subsequent impairment of antitumor immunity creates an immunotolerant microenvironment at the perineural interface, removing a critical barrier to PNI and facilitating unimpeded tumor invasion along nerve bundles.

Metabolic symbiosis between tumor cells and perineural cells constitutes a third ecological principle that sustains and amplifies PNI. In natural ecosystems, symbiotic metabolic relationships enable distinct organisms to exchange nutrients and energy, enhancing their mutual survival; this dynamic is recapitulated in the tumor-perineural microenvironment, where cross-feeding between tumor cells and perineural cells supports the invasive phenotype of both populations. A well-characterized example of this symbiosis is observed in CRC, where tumor cells rely on aerobic glycolysis (the Warburg effect) to produce and secrete large quantities of lactate. This lactate serves as a key metabolic substrate for Schwann cells, fueling their metabolic activity and survival. In return, Schwann cells secrete NGF, a neurotrophic factor that enhances the neurotropism of tumor cells, strengthening their ability to migrate toward and invade nerve tissue. This bidirectional metabolic cross-talk creates a self-reinforcing symbiotic loop that sustains the survival, proliferation, and invasive capacity of both tumor and perineural cells, thereby driving the progressive advancement of PNI[88].

Digestive-tract tumors with PNI exhibit marked heterogeneity: Tumor cells differ in their propensity for neural invasion and the immune-evasion mechanisms they utilize[89]. This heterogeneity not only hinders the development of universal therapies but also complicates the accurate prediction of treatment responses. Additionally, the PNI microenvironment forms unique niches that facilitate immune escape, and deciphering these PNI-specific evasion mechanisms to improve immunotherapy efficacy remains a key challenge. Meanwhile, immune-related adverse events and potential additive toxicities of combination regimens are major concerns, requiring careful balancing to preserve antitumor effects while managing toxicity[90,91]. Against this clinical and mechanistic backdrop, the present study focuses on the immune-related mechanisms of PNI, shedding light on the immunomodulatory pathways that drive tumor cell infiltration into nerves.

Notably, PNI progression is rarely mediated by a single factor. Other components of the TME, particularly TME stiffening driven by ECM stiffness, also play a pivotal role in promoting PNI and may engage in complex crosstalk with immune processes to synergistically accelerate this pathological process. ECM stiffness, induced by abnormal deposition and cross-linking of ECM components (e.g., collagen), not only directly modulates tumor cell behavior, activating mechanotransduction pathways such as the YAP/TAZ axis to enhance cell migration and invasiveness toward nerve bundles, but also reshapes the TME’s immune landscape. For example, a stiffened ECM can impair the infiltration and cytotoxic function of anti-tumor immune cells (e.g., CD8+ T cells and NK cells) by increasing tissue mechanical resistance and upregulating immune checkpoint molecules (e.g., PD-L1) on tumor-associated fibroblasts. Concurrently, it recruits and polarizes pro-tumor immune cells (e.g., M2-type macrophages and Tregs), whose secreted cytokines (e.g., TGF-β and IL-10) further reinforce ECM remodeling and nerve remodeling, creating a permissive microenvironment for PNI. Targeting this multi-factor regulatory network thus holds promise for developing novel therapeutic strategies to inhibit PNI in digestive-tract tumors.

To address the aforementioned challenges and translate these mechanistic insights into clinical practice, future efforts should focus on three key areas. First, identify robust PNI-relevant biomarkers, including both immune markers and indicators of the PNI process itself, to predict prognosis and therapeutic response[92]. Second, develop targeted agents that disrupt tumor-nerve interactions and rationally combine them with immunotherapies to enhance efficacy[93]. Ultimately, personalized treatment strategies integrating PNI status, the immune landscape, and genomic features will be essential to optimize outcomes for patients with PNI+ digestive-tract cancers[94].

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to professor Sai-Jun Mo for his invaluable guidance and insightful suggestions throughout this research. We also extend our thanks to the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University and the School of Basic Medical Sciences, Zhengzhou University, for providing the experimental platforms that made this study possible.

| 1. | Zhou Y, Song K, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Dai M, Wu D, Chen H. Burden of six major types of digestive system cancers globally and in China. Chin Med J (Engl). 2024;137:1957-1964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Arnold M, Abnet CC, Neale RE, Vignat J, Giovannucci EL, McGlynn KA, Bray F. Global Burden of 5 Major Types of Gastrointestinal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:335-349.e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 857] [Cited by in RCA: 1438] [Article Influence: 239.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (16)] |

| 3. | Li J, Mei S, Zhou S, Zhao F, Liu Q. Perineural invasion is a prognostic factor in stage II colorectal cancer but not a treatment indicator for traditional chemotherapy: a retrospective cohort study. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022;13:710-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Selvaggi F, Melchiorre E, Casari I, Cinalli S, Cinalli M, Aceto GM, Cotellese R, Garajova I, Falasca M. Perineural Invasion in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: From Molecules towards Drugs of Clinical Relevance. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:5793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fukuda Y, Tanaka Y, Eto K, Ukai N, Sonobe S, Takahashi H, Ikegami M, Shimoda M. S100-stained perineural invasion is associated with worse prognosis in stage I/II colorectal cancer: Its possible association with immunosuppression in the tumor. Pathol Int. 2022;72:117-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tao Q, Zhu W, Zhao X, Li M, Shu Y, Wang D, Li X. Perineural Invasion and Postoperative Adjuvant Chemotherapy Efficacy in Patients With Gastric Cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li J, Kang R, Tang D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of perineural invasion of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2021;41:642-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Melgarejo da Rosa M, Clara Sampaio M, Virgínia Cavalcanti Santos R, Sharjeel M, Araújo C, Galdino da Rocha Pitta M, Cristiny Pereira M, Jesus Barreto de Melo Rego M. Unveiling the pathogenesis of perineural invasion from the perspective of neuroactive molecules. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021;188:114547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Peng T, Guo Y, Gan Z, Ling Y, Xiong J, Liang X, Cui J. Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) Encourages the Neuroinvasive Potential of Pancreatic Cancer Cells by Activating the Warburg Effect and Promoting Tumor Derived Exosomal miRNA-21 Expression. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:8445093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen SH, Zhang BY, Zhou B, Zhu CZ, Sun LQ, Feng YJ. Perineural invasion of cancer: a complex crosstalk between cells and molecules in the perineural niche. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:1-21. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Wang M, Pu N, Bo X, Chen F, Zhou Y, Cheng Q. Significance and mechanisms of perineural invasion in malignant tumors. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1572396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fukuoka E, Yamashita K, Tanaka T, Sawada R, Sugita Y, Arimoto A, Fujita M, Takiguchi G, Matsuda T, Oshikiri T, Nakamura T, Suzuki S, Kakeji Y. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Increases PD-L1 Expression and CD8(+) Tumor-infiltrating Lymphocytes in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2019;39:4539-4548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li S, Mirlekar B, Johnson BM, Brickey WJ, Wrobel JA, Yang N, Song D, Entwistle S, Tan X, Deng M, Cui Y, Li W, Vincent BG, Gale M Jr, Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Ting JP. STING-induced regulatory B cells compromise NK function in cancer immunity. Nature. 2022;610:373-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 59.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hanks BA. Immune evasion pathways and the design of dendritic cell-based cancer vaccines. Discov Med. 2016;21:135-142. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Shi P, Yu Y, Xie H, Yin X, Chen X, Zhao Y, Zhao H. Recent advances in regulatory immune cells: exploring the world beyond Tregs. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1530301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Luna DE, Shinohara MM. New Molecular and Biological Markers in Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma: Therapeutic Implications. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2023;18:83-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cole SW, Nagaraja AS, Lutgendorf SK, Green PA, Sood AK. Sympathetic nervous system regulation of the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:563-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 388] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 39.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Han F, Zhang S, Zhang L, Hao Q. The overexpression and predictive significance of MMP-12 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2017;213:1519-1522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yang T, Chen M, Yang X, Zhang X, Zhang Z, Sun Y, Xu B, Hua J, He Z, Song Z. Down-regulation of KLF5 in cancer-associated fibroblasts inhibit gastric cancer cells progression by CCL5/CCR5 axis. Cancer Biol Ther. 2017;18:806-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Camuzi D, Buexm LA, Lourenço SQC, Grazziotin R, Guaraldi S, Valverde P, Rapozo D, Brooks JM, Mehanna H, Ribeiro Pinto LF, Soares-Lima SC. FBXL7 Body Hypomethylation Is Frequent in Tumors from the Digestive and Respiratory Tracts and Is Associated with Risk-Factor Exposure. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:7801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gallois C, Emile JF, Kim S, Monterymard C, Gilabert M, Bez J, Lièvre A, Dahan L, Laurent-Puig P, Mineur L, Coriat R, Legoux JL, Hautefeuille V, Phelip JM, Lecomte T, Sokol H, Capron C, Randrian V, Lepage C, Lomenie N, Kurtz C, Taieb J, Tougeron D. Pembrolizumab with Capox Bevacizumab in patients with microsatellite stable metastatic colorectal cancer and a high immune infiltrate: The FFCD 1703-POCHI trial. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53:1254-1259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhen Z, Shen Z, Sun P. Dissecting the Role of Immune Checkpoint Regulation Patterns in Tumor Microenvironment and Prognosis of Gastric Cancer. Front Genet. 2022;13:853648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kwak Y, Seo AN, Lee HE, Lee HS. Tumor immune response and immunotherapy in gastric cancer. J Pathol Transl Med. 2020;54:20-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kawasaki K, Noma K, Kato T, Ohara T, Tanabe S, Takeda Y, Matsumoto H, Nishimura S, Kunitomo T, Akai M, Kobayashi T, Nishiwaki N, Kashima H, Maeda N, Kikuchi S, Tazawa H, Shirakawa Y, Fujiwara T. PD-L1-expressing cancer-associated fibroblasts induce tumor immunosuppression and contribute to poor clinical outcome in esophageal cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2023;72:3787-3802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zafar S, Shehzadi R, Dawood H, Maqbool M, Sarfraz A, Sarfraz Z. Current evidence of PD-1 and PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors for esophageal cancer: an updated meta-analysis and synthesis of ongoing clinical trials. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2024;16:17588359231221339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Song S, Zhang Y, Duan X, Liu C, Du Y, Wang X, Luo Y, Cui Y. HIF-1α/IL-8 axis in hypoxic macrophages promotes esophageal cancer progression by enhancing PD-L1 expression. Cancer Gene Ther. 2023;30:358-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chiu YM, Tsai CL, Kao JT, Hsieh CT, Shieh DC, Lee YJ, Tsay GJ, Cheng KS, Wu YY. PD-1 and PD-L1 Up-regulation Promotes T-cell Apoptosis in Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:2069-2078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chen J, Ye X, Pitmon E, Lu M, Wan J, Jellison ER, Adler AJ, Vella AT, Wang K. IL-17 inhibits CXCL9/10-mediated recruitment of CD8(+) cytotoxic T cells and regulatory T cells to colorectal tumors. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Guo C, Dai X, Du Y, Xiong X, Gui X. Preclinical development of a novel CCR8/CTLA-4 bispecific antibody for cancer treatment by disrupting CTLA-4 signaling on CD8 T cells and specifically depleting tumor-resident Tregs. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2024;73:210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Khanmammadova N, Islam S, Sharma P, Amit M. Neuro-immune interactions and immuno-oncology. Trends Cancer. 2023;9:636-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Huang FF, Cui WH, Ma LY, Chen Q, Liu Y. Crosstalk of nervous and immune systems in pancreatic cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1309738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hajiasgharzadeh K, Somi MH, Sadigh-Eteghad S, Mokhtarzadeh A, Shanehbandi D, Mansoori B, Mohammadi A, Doustvandi MA, Baradaran B. The dual role of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in inflammation-associated gastrointestinal cancers. Heliyon. 2020;6:e03611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Schledwitz A, Xie G, Raufman JP. Exploiting unique features of the gut-brain interface to combat gastrointestinal cancer. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e143776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Qi YH, Yang LZ, Zhou L, Gao LJ, Hou JY, Yan Z, Bi XG, Yan CP, Wang DP, Cao JM. Sympathetic nerve infiltration promotes stomach adenocarcinoma progression via norepinephrine/β2-adrenoceptor/YKL-40 signaling pathway. Heliyon. 2022;8:e12468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wang K, Zhao XH, Liu J, Zhang R, Li JP. Nervous system and gastric cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2020;1873:188313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Wang ZQ, Sun XL, Wang YL, Miao YL. Agrin promotes the proliferation, invasion and migration of rectal cancer cells via the WNT signaling pathway to contribute to rectal cancer progression. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2021;41:363-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Huang T, Lin Y, Chen J, Hu J, Chen H, Zhang Y, Zhang B, He X. CD51 Intracellular Domain Promotes Cancer Cell Neurotropism through Interacting with Transcription Factor NR4A3 in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:2623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Chen S, Lin Z, He T, Islam MS, Xi L, Liao P, Yang Y, Zheng Y, Chen X. Topical Application of Tetrandrine Nanoemulsion Promotes the Expansion of CD4(+)Foxp3(+) Regulatory T Cells and Alleviates Imiquimod-Induced Psoriasis in Mice. Front Immunol. 2022;13:800283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Busuioc CI, Birla RD, Mitrea M, Ardeleanu C, Panaitescu E, Enache S, Iosif C. PD-L1 Expression in Esophageal and Gastroesophageal Junction Carcinoma, Correlation with the Immune Infiltrate - Preliminary Study. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2022;117:204-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Xu B, Chen L, Li J, Zheng X, Shi L, Wu C, Jiang J. Prognostic value of tumor infiltrating NK cells and macrophages in stage II+III esophageal cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7:74904-74916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Lin KX, Istl AC, Quan D, Skaro A, Tang E, Zheng X. PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors in cold colorectal cancer: challenges and strategies. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2023;72:3875-3893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Mahmoudian RA, Mozhgani S, Abbaszadegan MR, Mokhlessi L, Montazer M, Gholamin M. Correlation between the immune checkpoints and EMT genes proposes potential prognostic and therapeutic targets in ESCC. J Mol Histol. 2021;52:597-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Zheng Y, Li Y, Lian J, Yang H, Li F, Zhao S, Qi Y, Zhang Y, Huang L. TNF-α-induced Tim-3 expression marks the dysfunction of infiltrating natural killer cells in human esophageal cancer. J Transl Med. 2019;17:165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Smyth E, Thuss-Patience PC. Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Gastro-Oesophageal Cancer. Oncol Res Treat. 2018;41:272-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Saleh R, Taha RZ, Toor SM, Sasidharan Nair V, Murshed K, Khawar M, Al-Dhaheri M, Petkar MA, Abu Nada M, Elkord E. Expression of immune checkpoints and T cell exhaustion markers in early and advanced stages of colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020;69:1989-1999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Wu F, Sun G, Nai Y, Shi X, Ma Y, Cao H. NUP43 promotes PD-L1/nPD-L1/PD-L1 feedback loop via TM4SF1/JAK/STAT3 pathway in colorectal cancer progression and metastatsis. Cell Death Discov. 2024;10:241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Ma Y, He S, Gao A, Zhang Y, Zhu Q, Wang P, Yang B, Yin H, Li Y, Song J, Yue P, Li M, Zhang D, Liu Y, Wang X, Guo M, Jiao Y. Methylation silencing of TGF-β receptor type II is involved in malignant transformation of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Epigenetics. 2020;12:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Weng M, Zhao W, Yue Y, Guo M, Nan K, Liao Q, Sun M, Zhou D, Miao C. High preoperative white blood cell count determines poor prognosis and is associated with an immunosuppressive microenvironment in colorectal cancer. Front Oncol. 2022;12:943423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Saleh R, Elkord E. FoxP3(+) T regulatory cells in cancer: Prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Cancer Lett. 2020;490:174-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 42.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Li W, Peng A, Wu H, Quan Y, Li Y, Lu L, Cui M. Anti-Cancer Nanomedicines: A Revolution of Tumor Immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2020;11:601497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Liu M, Li F, Liu B, Jian Y, Zhang D, Zhou H, Wang Y, Xu Z. Profiles of immune cell infiltration and immune-related genes in the tumor microenvironment of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Med Genomics. 2021;14:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Laumont CM, Nelson BH. B cells in the tumor microenvironment: Multi-faceted organizers, regulators, and effectors of anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:466-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Mimura K, Kua LF, Xiao JF, Asuncion BR, Nakayama Y, Syn N, Fazreen Z, Soong R, Kono K, Yong WP. Combined inhibition of PD-1/PD-L1, Lag-3, and Tim-3 axes augments antitumor immunity in gastric cancer-T cell coculture models. Gastric Cancer. 2021;24:611-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Lee CH, Bae JH, Choe EJ, Park JM, Park SS, Cho HJ, Song BJ, Baek MC. Macitentan improves antitumor immune responses by inhibiting the secretion of tumor-derived extracellular vesicle PD-L1. Theranostics. 2022;12:1971-1987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Duong B, Banskota P, Falchook GS. T cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin Domain Containing Protein 3 (TIM-3) Inhibitors in Oncology Clinical Trials: A Review. J Immunother Precis Oncol. 2024;7:89-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Uto T, Fukaya T, Mitoma S, Nishikawa Y, Tominaga M, Choijookhuu N, Hishikawa Y, Sato K. Clec4A4 Acts as a Negative Immune Checkpoint Regulator to Suppress Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2023;11:1266-1279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Zhou YC, Zhu HL, Pang XZ, He Y, Shen Y, Ma DY. The IL-6/STAT3 Signaling Pathway Is Involved in Radiotherapy-Mediated Upregulation of PD-L1 in Esophageal Cancer. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2025;55:28-38. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Mozooni Z, Golestani N, Bahadorizadeh L, Yarmohammadi R, Jabalameli M, Amiri BS. The role of interferon-gamma and its receptors in gastrointestinal cancers. Pathol Res Pract. 2023;248:154636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Veen LM, Skrabanja TLP, Derks S, de Gruijl TD, Bijlsma MF, van Laarhoven HWM. The role of transforming growth factor β in upper gastrointestinal cancers: A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2021;100:102285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | de Araújo WM, Tanaka MN, Lima PHS, de Moraes CF, Leve F, Bastos LG, Rocha MR, Robbs BK, Viola JPB, Morgado-Diaz JA. TGF-β acts as a dual regulator of COX-2/PGE(2) tumor promotion depending of its cross-interaction with H-Ras and Wnt/β-catenin pathways in colorectal cancer cells. Cell Biol Int. 2021;45:662-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Geng D, Zhou Y, Wang M. Advances in the role of GPX3 in ovarian cancer (Review). Int J Oncol. 2024;64:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Huang K, Luo W, Fang J, Yu C, Liu G, Yuan X, Liu Y, Wu W. Notch3 signaling promotes colorectal tumor growth by enhancing immunosuppressive cells infiltration in the microenvironment. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Bakst RL, Xiong H, Chen CH, Deborde S, Lyubchik A, Zhou Y, He S, McNamara W, Lee SY, Olson OC, Leiner IM, Marcadis AR, Keith JW, Al-Ahmadie HA, Katabi N, Gil Z, Vakiani E, Joyce JA, Pamer E, Wong RJ. Inflammatory Monocytes Promote Perineural Invasion via CCL2-Mediated Recruitment and Cathepsin B Expression. Cancer Res. 2017;77:6400-6414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Peng J, Sheng W, Huang D, Venook AP, Xu Y, Guan Z, Cai S. Perineural invasion in pT3N0 rectal cancer: the incidence and its prognostic effect. Cancer. 2011;117:1415-1421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Selçukbiricik F, Tural D, Büyükünal E, Serdengeçti S. Perineural invasion independent prognostic factors in patients with gastric cancer undergoing curative resection. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:3149-3152. [PubMed] |

| 66. | Kim HE, Park SY, Kim H, Kim DJ, Kim SI. Prognostic effect of perineural invasion in surgically treated esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Thorac Cancer. 2021;12:1605-1612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Ma Y, Chen J, Yao X, Li Z, Li W, Wang H, Zhu J. Patterns and prognostic predictive value of perineural invasion in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:1287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Klempner SJ, Cowden ES, Cytryn SL, Fassan M, Kawakami H, Shimada H, Tang LH, Wagner DC, Yatabe Y, Savchenko A, Salcius J, Johng D, Chen J, Montenegro G, Moehler M. PD-L1 Immunohistochemistry in Gastric Cancer: Comparison of Combined Positive Score and Tumor Area Positivity Across 28-8, 22C3, and SP263 Assays. JCO Precis Oncol. 2024;8:e2400230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 69. | Sugiyarto G, Prossor D, Dadas O, Arcia-Anaya ED, Elliott T, James E. Protective low-avidity anti-tumour CD8+ T cells are selectively attenuated by regulatory T cells. Immunother Adv. 2021;1:ltaa001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Lee JS, Won HS, Sun S, Hong JH, Ko YH. Prognostic role of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Mohammadzadeh S, Khanahmad H, Esmaeil N, Eskandari N, Rahimmanesh I, Rezaei A, Andalib A. Producing Soluble Human Programmed Cell Death Protein-1: A Natural Supporter for CD4+T Cell Cytotoxicity and Tumor Cells Apoptosis. Iran J Biotechnol. 2019;17:e2104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Pen JJ, Keersmaecker BD, Heirman C, Corthals J, Liechtenstein T, Escors D, Thielemans K, Breckpot K. Interference with PD-L1/PD-1 co-stimulation during antigen presentation enhances the multifunctionality of antigen-specific T cells. Gene Ther. 2014;21:262-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Said SS, Ibrahim WN. Cancer Resistance to Immunotherapy: Comprehensive Insights with Future Perspectives. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15:1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Simonds EF, Lu ED, Badillo O, Karimi S, Liu EV, Tamaki W, Rancan C, Downey KM, Stultz J, Sinha M, McHenry LK, Nasholm NM, Chuntova P, Sundström A, Genoud V, Shahani SA, Wang LD, Brown CE, Walker PR, Swartling FJ, Fong L, Okada H, Weiss WA, Hellström M. Deep immune profiling reveals targetable mechanisms of immune evasion in immune checkpoint inhibitor-refractory glioblastoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9:e002181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Li Y, Zhou H, Liu P, Lv D, Shi Y, Tang B, Xu J, Zhong T, Xu W, Zhang J, Zhou J, Ying K, Zhao Y, Sun Y, Jiang Z, Cheng H, Zhang X, Ke Y. SHP2 deneddylation mediates tumor immunosuppression in colon cancer via the CD47/SIRPα axis. J Clin Invest. 2023;133:e162870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Ji Y, Xiao C, Fan T, Deng Z, Wang D, Cai W, Li J, Liao T, Li C, He J. The epigenetic hallmarks of immune cells in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2025;24:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Khalaf S, Toor SM, Murshed K, Kurer MA, Ahmed AA, Abu Nada M, Elkord E. Differential expression of TIM-3 in circulation and tumor microenvironment of colorectal cancer patients. Clin Immunol. 2020;215:108429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Gomes de Morais AL, Cerdá S, de Miguel M. New Checkpoint Inhibitors on the Road: Targeting TIM-3 in Solid Tumors. Curr Oncol Rep. 2022;24:651-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Zhou G, Noordam L, Sprengers D, Doukas M, Boor PPC, van Beek AA, Erkens R, Mancham S, Grünhagen D, Menon AG, Lange JF, Burger PJWA, Brandt A, Galjart B, Verhoef C, Kwekkeboom J, Bruno MJ. Blockade of LAG3 enhances responses of tumor-infiltrating T cells in mismatch repair-proficient liver metastases of colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1448332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Tu L, Guan R, Yang H, Zhou Y, Hong W, Ma L, Zhao G, Yu M. Assessment of the expression of the immune checkpoint molecules PD-1, CTLA4, TIM-3 and LAG-3 across different cancers in relation to treatment response, tumor-infiltrating immune cells and survival. Int J Cancer. 2020;147:423-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Li W, Huang Y, Zhou X, Cheng B, Wang H, Wang Y. CAR-T therapy for gastrointestinal cancers: current status, challenges, and future directions. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2024;57:e13640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Fabian KP, Malamas AS, Padget MR, Solocinski K, Wolfson B, Fujii R, Abdul Sater H, Schlom J, Hodge JW. Therapy of Established Tumors with Rationally Designed Multiple Agents Targeting Diverse Immune-Tumor Interactions: Engage, Expand, Enable. Cancer Immunol Res. 2021;9:239-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Chen TT, Li X, Zhang Y, Kang XJ, Zhang SF, Zhang T, Sangmao D, Zhu YJ, Zhang DK. Breaking down physical barriers: strategies to improve lymphocyte infiltration for effective neoantigen-based therapies. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1614228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Zhang D, Zhao J, Zhang Y, Jiang H, Liu D. Revisiting immune checkpoint inhibitors: new strategies to enhance efficacy and reduce toxicity. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1490129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Fabian KP, Kowalczyk JT, Reynolds ST, Hodge JW. Dying of Stress: Chemotherapy, Radiotherapy, and Small-Molecule Inhibitors in Immunogenic Cell Death and Immunogenic Modulation. Cells. 2022;11:3826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Wang R, Liu S, Chen B, Xi M. Recent Advances in Combination of Immunotherapy and Chemoradiotherapy for Locally Advanced Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:5168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Xu Q, Yi D, Jia C, Kong F, Jia Y. Immunotherapy plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in the first-line treatment for advanced gastric cancer/gastroesophageal junction cancer: a real-world retrospective study. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1463017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Jiménez MC, Prieto K, Lasso P, Gutiérrez M, Rodriguez-Pardo V, Fiorentino S, Barreto A. Plant extract from Caesalpinia spinosa inhibits cancer-associated fibroblast-like cells generation and function in a tumor microenvironment model. Heliyon. 2023;9:e14148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Ai D, Du Y, Duan H, Qi J, Wang Y. Tumor Heterogeneity in Gastrointestinal Cancer Based on Multimodal Data Analysis. Genes (Basel). 2024;15:1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Shieh C, Chalikonda D, Block P, Shinn B, Kistler CA. Gastrointestinal toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Ann Gastroenterol. 2021;34:46-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Bureš J, Kohoutová D, Zavoral M. Gastrointestinal toxicity of systemic oncology immunotherapy. Klin Onkol. 2022;35:346-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Liu Q, Ma Z, Cao Q, Zhao H, Guo Y, Liu T, Li J. Perineural invasion-associated biomarkers for tumor development. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;155:113691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Marshall HT, Djamgoz MBA. Immuno-Oncology: Emerging Targets and Combination Therapies. Front Oncol. 2018;8:315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Li T, Hu C, Huang T, Zhou Y, Tian Q, Chen H, He R, Yuan Y, Jiang Y, Jiang H, Huang K, Cheng D, Chen R, Zheng S. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Foster a High-Lactate Microenvironment to Drive Perineural Invasion in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2025;85:2199-2217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/