Published online Jan 24, 2026. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v17.i1.114913

Revised: October 24, 2025

Accepted: November 27, 2025

Published online: January 24, 2026

Processing time: 111 Days and 10.9 Hours

Melanoma, a highly immunogenic malignancy, has become a paradigm for immune-based therapies. Despite remarkable responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors, many patients exhibit primary or acquired resistance. These outcomes are largely driven by the composition and dynamics of the tumor microenvironment, which shape immune activation, suppression, and therapeutic respon

Core Tip: Melanoma represents a model disease for immuno-oncology, highlighting both the efficacy and limitations of immune-based therapies. Its highly immunogenic nature, coupled with the complexity of the tumor microenvironment, drives variable treatment responses and resistance to immune checkpoint blockade and targeted therapies. By integrating insights into tumor-immune interactions, resistance pathways, and predictive biomarkers, novel therapeutic strategies, particularly rational combinations of immunotherapy, targeted agents, and next-generation immunomodulators, are paving the way toward more durable and personalized clinical outcomes.

- Citation: Oliveira MMGL, Lemos CS, Brazão MLS, Rodrigues ALA, do Nascimento EDC, Cardoso EMP, Arantes MFF, de Melo FF. Immune landscape of melanoma: Tumor microenvironment, resistance mechanisms, and predictive biomarkers. World J Clin Oncol 2026; 17(1): 114913

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v17/i1/114913.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v17.i1.114913

Melanoma is one of the most lethal forms of skin cancer, responsible for more than 90% of deaths from cutaneous malignancies, although less common than other skin cancers[1]. It is a malignant tumor originating from melanocytes, the cells responsible for producing melanin. While these cells are primarily located in the skin, they can also be found in the eyes, ears, leptomeninges, gastrointestinal tract, and the mucous membranes of the oral, genital, and sinonasal regions[2]. A recent, comprehensive retrospective analysis of global melanoma trends revealed a significant increase in its worldwide burden, with notable disparities observed across genders, age groups, and regions from 1990 to 2021[3]. Despite considerable progress in understanding its pathology and developing effective treatments[4], melanoma incidence continues to rise globally[5,6]. Understanding the intricate mechanisms of melanoma, including its immune landscape, the tumor microenvironment (TME), and resistance pathways, is crucial for developing novel, targeted diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, seeing that a deeper comprehension of these factors can help refine our approach to the disease, ultimately improving patient outcomes and addressing the growing global health challenge posed by melanoma.

Over the next decade, melanoma-related mortality is expected to decline. This trend will be driven by enhanced diagnostic capabilities, relied on integrated diagnostic and predictive approaches that combine traditional clinicopathological evaluation with multiomic profiling of the tumor, its microenvironment, and host factors[2,7]. In this review, we discuss the dynamics of the melanoma TME and tumor immunogenicity, exploring their implications for immune evasion and therapy response. We also highlight epidemiology, future perspectives in the field, while considering the role of biomarkers in guiding patient stratification and prognosis.

Its development is multifactorial, resulting from the interplay of genetic susceptibility and environmental exposures. Ultraviolet (UV) radiation contributes to 60%-70% of cases, primarily through indirect DNA damage induced by UVA radiation[8-10]. Intense and intermittent sun exposure, particularly in fair-skinned, unacclimated individuals, significantly increases melanoma risk, with childhood sunburns further elevating susceptibility[10]. Phenotypic traits such as fair skin, blue or green eyes, blond or red hair, freckles, and inability to tan confer additional risk[8-10].

Family history is an important determinant: Approximately 5%-10% of melanomas occur in families with hereditary predisposition[10]. The presence of clinically atypical nevi, even in small numbers, is a strong predictor of subsequent melanoma; patients with more than 50 nevi, including at least one atypical, are considered high-risk[10,11]. The presence of dysplastic nevi, particularly with a family history, defines the atypical mole (dysplastic nevus) syndrome, and when coupled with a first-degree relative affected by melanoma, constitutes the FAMMM syndrome (Familial Atypical Multiple Mole and Melanoma), associated with markedly elevated lifetime risk[12].

Sex and tumor location show distinct patterns: Men are more frequently affected on the trunk, whereas women predominantly develop melanoma on the upper and lower extremities[11]. Men have a 1.5-fold higher risk compared to women, and by age 75, incidence is nearly three times greater[10]. Women tend to develop melanoma at younger ages, while incidence in men peaks later in life[11,13]. Socioeconomic status and comorbidities also modulate outcomes: Uninsured individuals have a 67% higher risk of melanoma-related mortality, and conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, Parkinson’s disease, and childhood cancers are associated with an increased risk of developing melanoma[9,11]. Occupational exposures, including UV radiation from welding, correlate with ocular melanoma, with French welders exhibiting a 7.3-fold higher risk compared to the general population[8].

Genetic mutations play a central role in melanoma predisposition. Germline alterations in cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A, microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (E318K), and BRCA1-associated protein 1 increase susceptibility, with BRCA1-associated protein 1 mutations linked to a tumor predisposition syndrome encompassing uveal and cutaneous melanoma, mesothelioma, and renal cell carcinoma[9]. Melanoma development is primarily driven by two mutational processes: Intrinsic age-related (clock-like) mutations and UV-induced mutations[1].

Globally, melanoma incidence has steadily increased over recent decades, with significant regional and population-based variations[1]. Between 1990 and 2021, global cases rose by 182.3%, deaths by 86.1%, and disability-adjusted life years by 63.7%[1]. Australia and New Zealand report the highest incidence rates, although younger populations show declining trends, likely due to prevention programs and early detection strategies[8,9,14]. In Europe, incidence continues to rise, particularly among men and individuals over 50 years, while mortality trends overall are decreasing[8,14].

In 2020, approximately 325000 new cases were reported, with the highest incidence in North America and Northern and Western Europe[8]. In the same year, Arnold et al[15], in their report on the global burden of melanoma, noted that there were an estimated 174000 men and 151000 women diagnosed, with 57000 deaths (32000 men, 25000 women). Regions of Asia, Africa, and Latin America exhibit relatively low incidence but disproportionately high mortality[9]. Overall, melanoma is a highly aggressive skin cancer with a globally rising incidence, and outcomes shaped by genetic susceptibility, environmental exposures, and healthcare access. Targeted prevention, early detection, and risk-based management remain essential to reduce its substantial global burden.

Melanoma is notably immunogenic, reflecting its high tumor mutational burden (TMB) and the consequent generation of a broad spectrum of neoantigens capable of activating the immune system. This high mutation rate increases the likelihood of neoantigen presentation recognizable by the immune system[16]. These neoantigens, primarily arising from somatic mutations induced by UV radiation, differ from normal tissues and are perceived as foreign, thereby evading central tolerance mechanisms[17]. Consequently, melanoma exhibits more pronounced responses to immunotherapy compared to most solid tumors[18-20]. TMB, as assessed through exome sequencing, correlates with the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), with highly mutated tumors demonstrating significantly higher response rates and survival[20,21]. Nonetheless, immunogenicity is not uniform across all subtypes. Acral, mucosal, and uveal melanomas exhibit lower TMB and reduced expression of immune-related genes, resulting in diminished therapeutic sensitivity[16,19]. Although numerous, neoantigens vary in their immunological relevance. Most represent “private” mutations unique to individual patients, which limits their applicability in universal strategies. Only 1 to 2 percent elicit spontaneous T-cell responses. However, when properly identified and validated, they serve as highly specific targets with minimal risk of autoimmunity[18,22,23].

In contrast, neoantigens derived from recurrent oncogenic hotspots, such as RAS.Q61K, offer greater therapeutic potential due to their more homogeneous presentation across tumors and patients[24]. Moreover, non-canonical neoantigens, originating from aberrant splicing events or non-coding regions, have been investigated to explain immune responses in tumors with intermediate or low TMB[18,22]. In addition, intratumoral heterogeneity adds an additional layer of complexity by generating tumor regions with distinct mutational and immunological profiles[18,22,24]. Therapeutic exploitation of neoantigens has advanced through different strategies, including personalized vaccines, individualized neoantigen-specific immunotherapy, and exosome-based platforms[22,25-27]. Experimental studies in murine melanoma models confirm that highly mutated tumors elicit robust cytotoxic T-cell responses and durable immune memory[28,29]. Furthermore, melanoma antigenicity can be further enhanced by presentation of peptides derived from endogenous retroviruses or intratumoral bacteria, which contribute to activation of tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes[17].

Effective antigen presentation relies on proper functioning of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). Antigen processing involves proteasomal degradation, transport via the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP), and loading onto polymorphic human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles, culminating in epitope display on MHC-I for CD8+ T-cell activation and MHC-II for CD4+ T-cell activation[18,30-32].

Conventional type 1 dendritic cells (cDC1s) are critical for cross-presentation. They ensure efficient display of tumor-derived neoantigens and enable robust priming of primary immune responses[23,28]. However, genetic defects in the presentation machinery can compromise this process. Alterations such as HLA loss of heterozygosity, β2-microglobulin (B2M) mutations, or interferon-γ (IFN-γ) signaling dysregulation, impair tumor peptide display and facilitate immune evasion[17,19,33,34].

Metabolic alterations and tumor hypoxia also influence this process: Elevated levels of oxidized lipids in DCs reduce cross-presentation capacity. In parallel, tumor mitochondrial activity regulates MHC-I and MHC-II expression, modulating tumor susceptibility to lymphocyte attack[22,31,33]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IFN-γ and interleukin (IL)-12, further enhance antigen presentation by upregulating MHC expression and promoting lymphocyte activation[18,22,30]. These mechanisms help explain why some patients with highly mutated melanoma fail to respond to ICIs, highlighting that immunogenicity is multifactorial and not solely dependent on TMB[21,31].

Immune response efficacy also hinges on the function of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), particularly DCs and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). DCs capture tumor antigens, migrate to lymph nodes, and prime CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. In doing so, they bridge innate and adaptive immunity[22,25]. The functional state of DCs determines their role: Immature DCs exhibit strong migratory capacity. In contrast, mature DCs express co-stimulatory molecules (CD80, CD83, CD86), which are essential for effective T-cell activation[20,25,30].

In melanoma, tumor-derived factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), IL-10, and prostaglandin E2 impair the previous process, promoting a tolerogenic phenotype and reducing antigen presentation efficiency[16,17,22,30,35]. Melanoma-derived exosomes exert dual effects. On one hand, they can induce DC dysfunction through delivery of fatty acids that enhance oxidative phosphorylation. On the other, they can also stimulate immature DCs to activate T cells, thereby potentiating antitumor responses[25,27].

Among APCs, cDC1s are particularly notable for recruiting and expanding polyclonal cytotoxic T cells, organizing tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) within the TME, and sustaining immune memory[22,28]. They secrete chemokines such as C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL) 9 and CXCL10 to recruit CD8+ T cells, and their function is modulated by the circadian rhythm, with CD80 expression regulated by the clock gene Bmal1[36]. Nonetheless, melanoma exerts strong immunosuppressive pressure. Vascular endothelial growth factor, TGF-β, and Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation impede cDC1 recruitment and CD8+ T-cell activation, thereby limiting lymphocyte infiltration and antitumor responses[22,30]. Extrinsic factors, including gut microbiota composition, also influence DC function and T-cell infiltration, affecting immunotherapy outcomes[20,21].

DC-based vaccines, particularly those incorporating neoantigens, aim to optimize CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell activation, generating durable responses and immune memory. Clinical trials with NeoVax have demonstrated long-term persistence of neoantigen-specific T cells, including T cell precursors of exhaustion capable of regeneration and interaction with DCs and B cells[18,20,27]. TAMs exhibit remarkable functional plasticity. M1 TAMs possess pro-inflammatory and antitumor activity, whereas M2 TAMs promote immunosuppression, angiogenesis, and tumor progression, correlating with poor prognosis[16,30,35]. Reprogramming TAMs, for example through IL-36α induction, can convert M2 TAMs into M1 TAMs, reversing tolerogenic environments and enhancing antitumor immunity[35].

Therapeutic reprogramming of DCs and cDC1s remodels the TME, promotes TLS formation, and recruits polyclonal T cells. Preclinical studies show that cytotoxic CD4+ T cells can directly eradicate tumor cells, while CD8+ depletion compromises tumor control at later stages[28]. Tumor differentiation status also influences immune escape: Dedifferentiation reduces melanocytic antigen expression, diminishing CD8+ T-cell activation. Silencing transcription factor 4 in preclinical models restored immunogenicity and enhanced anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) responses[34]. CD4+ CXCL13+ cell populations coordinate antitumor immunity by interacting with B cells and macrophages, promoting B-cell maturation and CD8+ T-cell activation. These populations are associated with dense lymphoid infiltrates, inflammatory chemokine expression (CXCL9-11), and improved clinical outcomes[32].

Experimental models, including genetically engineered mice, syngeneic lines, and humanized mice, allow integrated study of melanoma immunogenicity, assessing interactions among DCs, T cells, TAMs, and B cells, thereby overcoming limitations of immunocompromised xenografts and better recapitulating human immune responses[29]. Metabolic alterations in the TME, such as lactate accumulation and oxidized lipids, further modulate CD8+ T-cell and DC function, impacting antitumor efficacy. Consequently, combined strategies that reprogram DCs, stimulate T cells, and modulate the TME may maximize immunogenicity and improve therapeutic outcomes[22,31].

In conclusion, melanoma immunogenicity emerges from the dynamic interplay among neoantigen diversity, intratumoral heterogeneity, antigen presentation mechanisms, pro-inflammatory cytokines, metabolic microenvironment, and the coordinated activity of DCs, TAMs, and other immune cells during T-cell priming. This knowledge informs the development of combinatorial strategies, including neoantigen vaccines, DC manipulation, TAM reprogramming, and microbiota modulation, aimed at enhancing therapeutic efficacy and overcoming tumor-induced immune resistance.

The TME is crucial in all stages of tumorigenesis and is defined by hypoxia, acidosis, and a heterogeneous composition. In addition to malignant cells, it encompasses stromal cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), multiple immune cell types, blood and lymphatic vessels, and an extracellular matrix embedded with cytokines and other signaling molecules[37]. This “tumor niche” also includes a malignant cells together with various supporting cell types, including keratinocytes, cancer stem cells, CAFs, endothelial cells, and immune cells. Through this network, the TME influences melanoma progression and therapeutic response[38], its heterogeneity, particularly due to cancer stem cells, is strongly associated with aggressive tumor behavior[39]. Building upon the immunogenic potential described earlier, the TME ultimately determines whether immune responses are sustained or suppressed.

CAFs represent one of the most abundant cell population within the TME. During tumor development, fibroblasts adjacent to cancer cells, particularly reticular fibroblasts, differentiate into CAFs[40], a process that occurs primarily through epigenetic modifications and activation of specific transcription factors, without significant genomic alterations[41]. Male and female fibroblasts differ in their behavior. Male fibroblasts exhibit chronic oxidative stress, impaired DNA repair, and secrete factors that enhance melanoma invasiveness. In contrast, female fibroblasts more effectively neutralize reactive oxygen species and maintain robust DNA repair. These differences highlight that melanoma invasion and resistance to targeted therapy are sex- and age-dependent[40,42].

Activated CAFs in melanoma secrete a variety of factors that remodel the extracellular matrix, promote melanoma cell migration and invasion, enhance cancer cell viability, and modulate immune responses. Moreover, these factors include proteases and structural proteins that alter the extracellular matrix, growth factors and cytokines that support tumor growth and survival, and immunomodulatory molecules[41,43]. In melanoma, CAFs promote tumor aggressiveness through pro-inflammatory activity, characterized by increased expression of cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and CXCL8, as well as multiple metalloproteinases, which collectively enhance tumor invasion and progression[44,45]. Macrophages are an abundant immune cell type within the TME, exhibiting functional differences based on their origin and activation pathway. Tissue-resident macrophages contribute to the early stages of tumor development[46] and metastasis by creating a permissive environment for cancer cell colonization. This effect is partly mediated through suppression of DC activity and reduced CD4+ T cells activation[47].

Together, these mechanisms demonstrate how the tumor orchestrates immune evasion by inducing both tolerogenic DCs, which limit T-cell activation locally, and immunosuppressive M2 macrophages, which broadly dampen immune responses within the TME. This dual strategy reinforces tumor survival and resistance to immunotherapy, illustrating how innate immunity can be reprogrammed by tumor-derived cues to favor immune evasion. Furthermore, as tumors progress, bone marrow-derived macrophages infiltrate the TME. These macrophages can later enhance metastatic potential by promoting the spatial rearrangement of tumor cells[48]. Within the TME, macrophages can be classified as M1 macrophages, which have pro-inflammatory and antitumor functions, or M2 macrophages, which are immunosuppressive and facilitate tumor progression[47]. Notably, conjunctival melanoma cells release substantial amounts of lactate in addition to cytokines, attracting macrophages and promoting their polarization toward the M2 phenotype[49]. In addition, exosomes secreted by TME cells further enhance this polarization[50].

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are represented by all major subpopulations, including CD3+CD4+ helper T-cells, CD3+CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells, forkhead box P3+ regulatory T-cells (Tregs), and CD20+ B-cells[37,51]. Firstly, TLS, ectopic lymph node-like formations, are primarily composed of B-cell-rich follicles, with a minor population of T-cells, reflecting their organized immune architecture[52]. A recent study suggests that TLS can serve as a potential diagnostic and prognostic marker in cancer: Mature TLSs are identifiable by CD23 expression, which marks follicular dendritic cells within germinal centers. Immunohistochemical detection of CD23 allows for reliable identification of clinically relevant TLSs, offering a standardized approach to evaluate TLS presence and maturity. Therefore, CD23 immunohistochemistry provides a practical and reproducible tool for assessing TLSs in patient tumor samples. The presence of mature TLSs is associated with better prognosis because they organize B cells and T cells into functional structures that enhance antigen presentation, promote effective anti-tumor immunity, and support robust immune responses to therapy[53,54]. Collectively, CAF activation, macrophage polarization, and T-cell exclusion converge to create a profoundly tolerogenic niche. These cellular and molecular events transition directly into the broader mechanisms of immunosuppression discussed in the following section.

Immune evasion mechanisms encompass strategies by which pathogens and tumor cells are able to circumvent the host’s immune surveillance. In this sense, although the immune system is highly coordinated and adaptive, these agents are able to develop mechanisms to persist, proliferate, and establish chronic infections or advance the process of tumor progression, despite active immune defenses[55-57]. One of the most relevant immune evasion processes occurs in melanoma. In this context, because it is a highly immunogenic tumor, melanoma tends to show more consistent responses to immunotherapies based on ICIs, since the immune system recognizes its neoantigens relatively effectively. However, despite this therapeutic potential, tumor evasion mechanisms play a central role in clinical treatment failure and can be classified as primary resistance and acquired resistance[58]. Primary resistance occurs when the immune system fails to generate an initial antitumor response, whereas acquired resistance develops after an initial response, followed by tumor adaptations that allow immune escape[59].

The TME expresses immune checkpoint molecules, such as PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1), which interacts with specific receptors on lymphocytes, inhibiting their activity and, consequently, suppressing the antitumor immune response[60]. The treatment of advanced melanoma has been marked by the use of checkpoint inhibitors, which block critical targets such as PD-1/PD-L1 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4)[61,62], factor that allows the reactivation of T cell effector function. These therapies have shown significant gains in survival, as well as higher response rates when compared to traditional approaches[63]. However, immune evasion mechanisms continue to pose a substantial challenge, as approximately 40% or more of patients do not respond to treatment from the outset, constituting a clear example of primary resistance[64,65].

Among the primary resistance mechanisms in melanoma, one that stands out is the failure of T cell priming, a process in which naive T lymphocytes cannot be activated and differentiated into effector cells capable of eliminating tumor cells[66]. This initial stage of the immune response is fundamental to the success of immunotherapies and depends on two key elements: The presence of immunogenic tumor antigens[67] and the efficient performance of APCs[68]. In poorly immunogenic tumors, often associated with low TMB, neoantigen production is reduced, which limits the immune system’s ability to recognize the tumor as a threat and initiate an adaptive response[69-71]. In this context, conventional dendritic cells of the CD103+/cDC1 subtype play a central role in melanoma, as they are highly specialized in interacting with CD8+ T cells and inducing their differentiation into effector cells[72,73]. Thus, changes in the maturation or function of these cells can seriously compromise the initial activation of T cells[74]. When this step fails, ICIs, which depend on previously activated T cells to exert their effect, lose their efficacy, culminating in primary resistance to treatment[66].

In addition, another primary resistance mechanism in melanoma involves defects in antigen presentation by MHC-I, which acts as a cell presenter, displaying protein fragments so that CD8+ T cells, enabling tumor cell elimination[75]. The MHC-I complex consists of the HLA-A, HLA-B and HLA-C heavy chains associated with B2M. Integrity of these components is crucial for assembly, stability, and transport of the complex to the cell surface[76,77]. However, alterations in B2M, such as mutations or deletions, compromise MHC-I functional expression, reducing T-cell recognition and cytotoxicity against tumor cells[78]. Additionally, TAP1 and TAP2 transporters shuttle peptides from the cytosol to the endoplasmic reticulum for loading onto MHC-I. Dysfunction of these transporters prevents proper antigen processing and presentation[79]. Additionally, genetic or epigenetic alterations in the HLA-A, HLA-B and HLA-C genes may decrease the display of antigens on the tumor surface, further reinforcing immune evasion[80].

Primary resistance in melanoma may also be related to the absence of lymphocyte infiltration in the tumor, a phenomenon known as “cold tumors”[61]. Thus, unlike “hot tumors”, in which there is an abundant presence of CD8+ T cells in the tumor parenchyma and an active inflammatory response, cold tumors exhibit restricted distribution or even absence of these cells, which compromises the effectiveness of ICIs[81]. In this sense, the difficulty in recruiting T cells to the TME stems from the low production of chemokines such as CXCL9 and CXCL10, which are required to establish the gradient for T-cell migration[82]. In addition, adequate expression of chemokine receptors, such as C-X-C chemokine receptor 3, on the lymphocytes themselves is essential for the homing. Deficiency in these receptors further limits tumor infiltration[83].

Additional factors also reinforce this phenotype: Physical barriers, such as dense extracellular matrix and CAFs, which restrict the passage of cells[84]; and metabolic barriers, such as hypoxia, the accumulation of adenosine and lactate, and the reduction of essential nutrients, which compromise the survival and effector activity of lymphocytes[85]. Finally, primary resistance in melanoma can also result from defects in inflammatory signaling, such as the pathway mediated by IFN-γ[86], which plays a central role in activating the immune response, stimulating dendritic cells and macrophages to increase antigen presentation[87]. IFN-γ binding to its MHC-I receptor activates the Janus kinase (JAK) 1 and JAK2 kinases, which phosphorylate the signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 transcription factor, promoting the transcription of genes involved in antigen presentation and tumor apoptosis[88]. Thus, the mutation or loss of function of JAK1 or JAK2 compromises this cascade, preventing the response to IFN-γ and the expression of MHC-I, which hinders the detection and destruction of tumor cells by T lymphocytes[86]. This block in IFN-γ signaling prevents the proper activation of the immune response even in the presence of ICIs. Therefore, defects in JAK1, JAK2 or signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 interrupt communication between immune and tumor cells, reinforcing immune evasion and consolidating the therapeutic failure observed in a significant proportion of melanoma patients[89].

As pointed out previously, the introduction of ICIs, particularly the monoclonal antibodies targeting PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4, revolutionized therapeutic strategies in several types of cancer, including melanoma. Although ICIs have demonstrated clinical effectiveness, acquired resistance has been observed, often mediated by the upregulation of alternative inhibitory pathways such as T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3 (TIM-3) and lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG-3)[90].

The inhibitory immune checkpoint TIM-3 is expressed on T cells and various other immune cells, such as mast cells. Among its ligands galectin-9 is particularly relevant, as it can be produced by neoplastic melanocytes. The interaction between TIM-3 and galectin-9 contributes to T cell dysfunction and immune evasion in melanoma[91]. This process occurs through intracellular calcium signaling activated by the engagement of TIM-3 and its ligand, leading to cell death, therefore mediating immune inhibition. Blockade of this interaction has shown success in restoring the function of exhausted CD8+ T cells, reinforcing its significance in acquired resistance[92]. One study[92] revealed mRNA expression of TIM-3 and galectin-9 in melanoma cells across all analyzed lesions, at levels comparable to those observed in TILs, B cells, natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, endothelial cells, and CAFs. Additionally, co-expression of both genes was detected in 42.6% of melanoma cells and in 79.4% of T cells.

The acquired resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy has also been associated with TIM-3. The upregulation of this protein has been perceived in metastatic melanoma patients who developed adaptive immune resistance. Experimental studies in mice have shown that TIM-3 blockade enhances CD8+ T cells function and survival, reinforcing its role in the process[59]. These findings highlight the broad expression of TIM-3 in the TME, supporting their relevance as key factors in immune evasion and as promising therapeutic targets in the management of this malignancy[59,93].

The other inhibitory immune checkpoint is the LAG-3, which is expressed on tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, among CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. One of its most relevant ligands is the MHC-II, the binding between LAG-3 and MHC-II is significantly stronger than that of CD4, impairing T-cell receptor signaling. The inhibitory effect is a consequence of both the competition with CD4 for MHC-II binding and inhibitory signals delivered through the unique cytoplasmic tail of LAG-3[94].

In relation to acquired resistance to ICIs, the role of LAG-3 is being increasingly documented; a non-cleavable form of it resulted in resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy by impairing CD4+ T cell function, compromising CD8+ T cell responses[95]. Simultaneous deficiency of PD-1 and LAG-3 in CD8+ T lymphocytes in murine models has shown improved tumor clearance and survival, highlighting the positive effects of dual inhibition[96]. In conclusion, LAG-3 has been identified as one of the compensatory immune checkpoints upregulated after blockade of PD-1 and CTLA-4, highlighting its role as an essential mediator of adaptive resistance and an important therapeutic target[97].

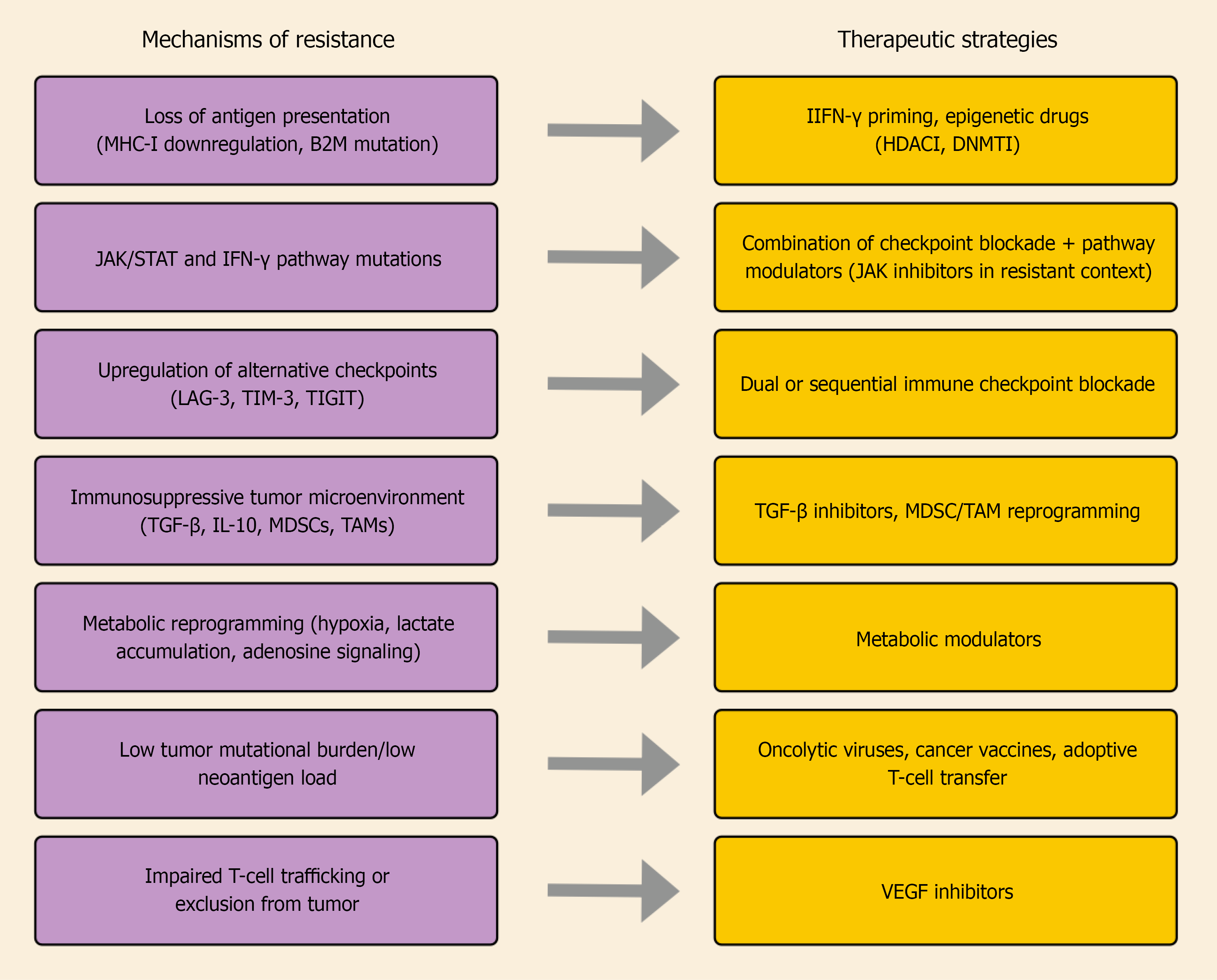

In summary, despite substantial progress in understanding melanoma resistance, most evidence remains derived from preclinical or early translational studies, and clinical validation is still limited. Future work should prioritize integrating genomic, metabolic, and microenvironmental data to clarify which mechanisms predominate in specific patient subgroups. Diverse biological processes contribute to primary and acquired resistance to ICIs in melanoma. These mechanisms, together with the emerging therapeutic strategies aimed at overcoming them, are schematically summarized in Figure 1.

Immunosuppression in the melanoma TME can be understood as a dynamic process, characterized by rapid and potentially reversible mechanisms. Within the TME, immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β, together with regulatory cells present in the tumor stroma, interact in a coordinated manner to inhibit both the activation and cytotoxic function of T cells and NK cells. As a result, there is a significant impairment of the effector immune response against neoplastic cells, favoring tumor progression[98,99].

The melanoma TME harbors a wide range of soluble factors capable of rapidly and dynamically modulating the immune response[100]. Unlike structural defects in antigen presentation, this immunosuppression is predominantly mediated by chemical signals, which have a direct effect on inhibiting the activation of local immune cells[100]. In addition, the intense communication established between tumor cells and immunoregulatory cells, such as Tregs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and TAMs, contributes to the maintenance of a tolerogenic environment, reinforcing and amplifying the suppression of the anti-tumor response[101].

Overall, the secretion of TGF-β has multiple effects on different cell populations[102], because, at the same time that it blocks clonal expansion and the effector function of CD8+ T lymphocytes and NK cells, it also favors the differentiation and maintenance of Treg, thus consolidating a tolerogenic TME[103]. Additionally, TGF-β acts on APCs, reducing the expression of co-stimulatory molecules and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which compromises the adequate priming of T lymphocytes and limits the induction of effective immune responses[104]. Furthermore, in TAMs and MDSCs, this pathway induces more immunoregulatory phenotypes, amplifying the local suppression cascade[105]. Ultimately, such immediate effects of TGF-β not only significantly reduce anti-tumor cytotoxicity, but also favor mechanisms of resistance to ICI-based immunotherapies, such as anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4, since the efficacy of these strategies depends on the presence and persistence of functional effector T cells in the TME[106].

IL-10 plays a crucial role in melanoma immune evasion, being secreted by tumor cells, Tregs, MDSCs and regulatory B cells[107]. This cytokine compromises the effectiveness of the anti-tumor response, since it inhibits the production of pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-12 and IFN-γ and, concomitantly, impairs antigen presentation by dendritic cells, which decreases the expression of MHC-II molecules and co-stimulatory signals[108,109]. Concurrently, IL-10 favors the expansion and maintenance of Tregs, which reinforces an immunosuppressive microenvironment and significantly limits the effector activity of T cells[110]. Thus, these mechanisms converge to reduce the effectiveness of immunotherapies based on ICIs, contributing to the development of tumor resistance and an unfavorable clinical prognosis[78].

Overall, immunosuppressive pathways in melanoma act through interconnected and often overlapping mechanisms. Although IL-10 and TGF-β are consistently identified as central mediators, their relative impact varies across experimental models and clinical cohorts[102-110]. Some reports highlight TGF-β as the dominant suppressor of cytotoxic T-cell function, while others attribute greater weight to MDSC activity[101,105].

Recently, substantial advances in biomarker discovery yielded valuable insights into patient responses to treatments, helping doctors tailor strategies more specifically. In this scenario, predictive biomarkers serve as essential tools to identify those most likely to respond to immunotherapy and reduce unnecessary exposure to toxicities. Various types of biomarkers have been progressively discovered and explored, ranging from molecular markers to cellular profiles of the TME, liquid biomarkers, and imaging parameters. This diversity reflects the complexity of the immune response in melanoma and justifies the search for new approaches[111].

Regarding molecular biomarkers, PD-L1 is an important molecular biomarker in clinical trials for melanoma. Its relevance lies in the ability to predict the clinical response to therapies with ICIs. Studies show that tumors with PD-L1 expression present a greater infiltration of immunological cells in the TME. This characteristic is usually connected to more favorable clinical outcomes, such as longer survival[112,113]. This correlation shows more favorable results in PD-L1 positive tumors. Despite its importance, evaluating PD-L1 is still complex, mainly due to tumor heterogeneity, since its variation occurs not only between different patients, but also in different regions of the tumor, and this variability often limits its reliability in using it as a single biomarker. In addition, diversity in laboratory methods and dynamic changes in expression over time make it difficult to detect.

Another challenge is the fact that PD-L1 is not exclusive to tumor cells and can also be found on immune cells. This can make the interpretation of results difficult, as it increases the likelihood of incorrect results, such as false positives. In spite of these limitations, PD-L1 remains one of the most valuable and complementary biomarkers for selecting patients as candidates for ICI therapies in melanoma. Ongoing research efforts are currently exploring the role of other markers, such as PD-L2, to further improve response prediction[113]. PD-L1 remains the most extensively evaluated predictive biomarker in melanoma. It is routinely assessed in clinical trials (e.g., KEYNOTE-006, CheckMate-067) but not yet standardized for regulatory use due to intra-tumoral heterogeneity and variability[112,113].

The search for new biomarkers involves the association between TMB and the success of immunotherapy in melanoma. Furthermore, a relationship was observed in therapy with antibody against anti-PD-L1 and antibody anti-CTLA-4, demonstrating the need for subsequent studies to reduce and eliminate heterogeneity factors. So PD-L1 expression and TMB may be independent or complementary biomarkers in patient selection for immunotherapy[114].

At the cellular level, the immune infiltrate in the TME plays a fundamental role in the response to immunotherapy. A high frequency of CD8 T lymphocytes infiltration has been widely linked to improved prognosis and higher response to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Zhang et al[115] examined the relationship between superior antitumor function of CD8 T cells and enhanced fatty acid catabolism and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in their report. Equally crucial is the ratio CD8/Treg. Tregs exert immunosuppressive effects, so an unfavorable ratio, when there is a low number of CD8 and a high number of Tregs, is expected to lead to worse outcomes. Gandini et al[116] reported that melanoma patients with a high CD8/Treg ratio exhibited significantly longer overall survival during therapy with ICIs. For this reason has become a reliable functional biomarker that shows the balance between effector and suppressor mechanisms in the immune response.

In addition to molecular and cellular biomarkers, liquid biomarkers have gained significance in the monitoring of melanoma, offering prognostic and predictive information in a minimally invasive way. For instance, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is one of the most studied topics today. Gracie et al[117] revealed that detectable levels of ctDNA in patients with metastatic melanoma are related to worse prognosis and lower response to therapy. Similarly, Gandini et al[116] investigated the persistent presence of ctDNA before and during treatment, noticing its links to reduced overall survival, reinforcing its value as a predictive biomarker, mainly in patients with advanced stage melanoma. In a more recent analysis, Liu et al[118] demonstrated that ctDNA detection in patients after primary treatment may indicate minimal residual disease coupled with an increased risk of recurrence. This highlights how this detection and monitoring plays a notable role in post-treatment patient follow-up. Currently, ctDNA is being incorporated into ongoing phase II-III trials to monitor minimal residual disease and dynamic treatment response, reinforcing its potential as a real-time predictive biomarker[116-118].

Circulating tumor cells also are relevant potential biomarkers. Mannino et al[119] used microfluidics techniques to phenotypically characterize melanoma circulating tumor cells and provide evidence that, as well as counting, it is possible to explore notable functional properties, such as PD-L1 expression. Finally, imaging biomarkers such as positron emission tomography (PET) derived metabolic parameters, such as metabolic tumor volume and total lesion glycolysis, have been consistently associated with clinical outcomes in melanoma. In this regard, in the assessment of staging and prognosis, metabolic tumor volume and total lesion glycolysis provide significant data, complementing traditional imaging approaches[120].

Outside melanoma, these parameters have also been validated in broader oncological settings, such as lung cancer and lymphoma, reiterating their role as prognostic indicators[121]. In the context of cutaneous malignant melanoma monitoring, researchers have already documented the high accuracy of PET in disease staging, however the need for further randomized studies that associate the exam as a form of predictive monitoring[122]. Moreover, a good understanding tumor biology and the chemokine environment in its entirety involves receptor-targeted imaging and multiplexed mass cytometry, enabling more personalized and comprehensive therapeutic strategies[123].

Additionally, a correlation between the uptake of the radiopharmaceutical and the clinical response to immunotherapy was demonstrated by a research of the use of 89Zr-nivolumab (nivolumab radiolabeled with zirconium-89 for PET imaging) for PD-1 imaging[124]. Simultaneously, the tumoral melanin directed image was explored as a specific molecular target of melanoma. Pandit-Taskar et al[125] used radiolabeled anti-melanin antibodies for PET, showing that it’s possible to detect metastatic lesions with high sensitivity, enhancing result. This approach has the potential to refine not only the functional assessment but also the molecular analysis in clinical settings of melanoma, although still in the initial clinical investigation phase.

In summary, despite the problems related to the lack of methodological standardization, tumor heterogeneity, and large-scale validation, predictive biomarkers are a fundamental pillar for melanoma oncology. Recent evidence points to combinations of multiple biomarkers as a strategy to address these difficulties, which would help to satisfactorily reduce the limitations of using single markers in isolation[126]. Furthermore, this evidence reinforces that the division into molecular subtypes identified by multi-omics analyses can help personalize therapeutic approaches in melanoma, combining immunotherapy, targeted therapies, and other interventions based on the biological profile of each subtype[127].

Despite substantial progress, conflicting findings remain among studies evaluating biomarker performance in melanoma. For instance, while several trials report that high PD-L1 expression correlates with improved response to anti-PD-1 therapy, others demonstrate objective responses even in PD-L1-negative tumors, indicating that PD-L1 alone is insufficient as a predictive tool[112-114]. Similarly, although a high TMB has been associated with enhanced immunogenicity, subsequent meta-analyses revealed inconsistent correlations between TMB levels and survival across melanoma subtypes and treatment regimens[21,114]. Together, these findings highlight that no single biomarker currently provides reliable prediction across all clinical contexts, reinforcing the need for integrative, multi-parameter approaches combining molecular, immune, and imaging data.

For many years, the management of advanced-stage cancer has faced major challenges due to the scarcity of effective therapies. Individuals with inoperable metastatic tumors were compelled to undergo chemotherapy, which is frequently associated with severe side effects and high rates of disease recurrence[128]. The elucidation of oncogenic drivers has enabled the advancement of targeted therapies, establishing the foundations of personalized medicine. In the context of melanoma, this progress has been reflected in the success of specific agents against B-Raf proto-oncogene (BRAF) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) proteins, which have demonstrated relevant clinical efficacy in patients carrying activating BRAF mutations.

Moreover, the inhibition of immune checkpoints through CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade has shown substantial therapeutic benefits, eliciting significant responses regardless of the tumor’s mutational status[129]. From this perspective, the assessment of biomarkers before and during treatment proves essential to identify patients with a higher or lower likelihood of responding to ICI-based therapies, thereby minimizing the risk of inappropriate drug use[130]. In light of this, it becomes critically important to define predictive biomarkers capable of guiding immunotherapy, as well as to explore therapeutic alternatives for patients who do not respond to conventional strategies with ICIs[131]. Table 1 summarizes ongoing or recently completed clinical trials of emerging combination strategies in melanoma.

| Combination therapy | NCT ID | Phase | Status | Mechanism/intervention |

| Nivolumab + relatlimab (anti-LAG-3) | NCT03470922 | III | Active, not recruiting | Dual checkpoint blockade (PD-1 + LAG-3) |

| Spartalizumab (anti-PD-1) + LAG525 (anti-LAG-3) | NCT03365791 | II | Completed | Dual checkpoint blockade |

| Cemiplimab (anti-PD-1) + fianlimab (anti-LAG-3) | NCT03005782 | I/II | Active, not recruiting | Dual checkpoint blockade |

| Nivolumab + BMS-986253 (anti-IL-8) | NCT03400332 | I/II | Recruiting | Inhibition of pro-tumoral chemokine IL-8 |

| Pembrolizumab + STING agonist (MK-1454) | NCT03010176 | I | Recruiting | Activation of innate immune cGAS-STING pathway |

| Nivolumab + oncolytic virus RP1 | NCT03767348 | II | Recruiting | Oncolytic virus combined with PD-1 blockade |

Immune checkpoint blockades targeting CTLA-4 and PD-1 have become therapeutic paradigms in modern oncology, transforming the management not only of melanoma but also significantly impacting the treatment of various other types of cancer[132,133]. A notable feature of CTLA-4 inhibition is the durability of antitumor responses, observed in approximately 10% of patients with melanoma. Similarly, antibodies targeting PD-1 and PD-L1, still in the early stages of clinical development, have demonstrated objective responses in about one in three patients with advanced melanoma, many of which have persisted for over one year[134]. Furthermore, CTLA-4 exerts an immunosuppressive effect by indirectly attenuating signaling through the co-stimulatory receptor CD28. By restricting CD28-mediated activation during antigen presentation, CTLA-4 raises the activation threshold of T cells, thereby reducing immune responses against low-immunogenicity antigens, including self and tumor antigens[130].

The treatment of advanced melanoma has been significantly improved with the development of ICIs. Among these, antibodies targeting PD-1, namely nivolumab and pembrolizumab, were approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2014 for patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma[135]. Studies indicate that both anti-PD-1 antibody monotherapy and the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab constitute effective strategies for the treatment of advanced melanoma. Moreover, ipilimumab has demonstrated significant activity both as a single agent and in combination with other therapies, including cancer vaccines. These regimens substantially increase the objective response rate and prolong progression-free survival, while exhibiting a lower frequency of adverse events compared to chemotherapy or ipilimumab alone[133,136].

The combination of CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade is supported by the complementarity of their mechanisms of action. While CTLA-4 inhibition promotes the activation and clonal expansion of T cells in the lymph nodes, PD-1 pathway disruption within the TME preserves the cytotoxic function of these cells by preventing their suppression by PD-L1 on neoplastic cells or by infiltrating plasmacytoid dendritic cells[137]. The combination of these blockers demonstrates greater efficacy, resulting in an increased number of differentially expressed T cell genes compared to either agent alone or to the sequential administration of both. However, the underlying mechanisms are not yet fully understood.

Moreover, as previously shown, although they provide durable responses and manageable toxicity, they benefit only a subset of patients when administered as monotherapy[128,138]. A recent phase 1 analysis showed that the combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab had already demonstrated encouraging results, with an objective response rate of approximately 61%, including complete regressions in around 20% of patients[139]. These preliminary findings were confirmed and expanded in a phase 3 clinical trial, in which the combination demonstrated a higher objective response rate, reaching 57%, compared to 19% for ipilimumab and 44% for nivolumab administered as monotherapy, as well as a longer median progression-free survival, further reinforcing the superiority of the combination therapy over individual regimens[139,140].

Furthermore, a relevant clinical benefit was observed, reflected in reduced tumor progression or death in individuals receiving combination therapy compared to monotherapy approaches. Data from preclinical models indicate that the combination increases the ratio of effector to Tregs and enhances the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α, suggesting differences in the modulation of cellular populations compared to single-agent therapies[138,141].

Despite the advances achieved with targeted therapies and immunotherapies, the treatment of melanoma still faces significant obstacles. Acquired resistance to BRAF/MEK inhibition, combined with the relatively low response rates to ICIs, constitutes a persistent clinical challenge, remaining one of the major hurdles in the management of melanoma[142-144]. Between 40% and 50% of melanomas harbor activating BRAF mutations. Patients with this profile may respond to treatment with BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi) and MEK inhibitors (MEKi), which block the MEK (MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase) signaling pathway[145]. Although the initially observed high objective response rates, these effects are generally short-lived, resulting in a median progression-free survival of 6 to 7 months, as the development of acquired resistance occurs with high frequency[146,147].

The BRAFi, in addition to inhibiting cell proliferation, also modulates the TME by promoting antigen presentation and facilitating the activation of specific T cells, thereby strengthening the antitumor immune response. Some studies suggest that the combined administration of BRAFi and MEKi provides significant therapeutic benefits. This strategy reduces adverse effects resulting from paradoxical MEK pathway activation in wild-type BRAF cells and, simultaneously, may enhance treatment efficacy by more consistently inhibiting tumor proliferative signaling. Moreover, compared to BRAFi monotherapy, the combination of these inhibitors delays the onset of resistance and reduces the occurrence of hyperproliferative damage[145-147]. Table 2 reviews major published clinical trials evaluating combination therapies in advanced melanoma.

| Combination therapy | Study | Phase | Population | Key outcomes | Ref. |

| Nivolumab + ipilimumab | CheckMate 067 | III | Untreated advanced melanoma | ORR: Approximately 57%; 5-year OS: Approximately 52% | [64,163] |

| Relatlimab + nivolumab | RELATIVITY-047 | II/III | Untreated advanced/metastatic melanoma | PFS: 10.1 months vs 4.6 months (vs nivolumab alone) | [164] |

| Pembrolizumab + T-VEC (oncolytic virus) | MASTERKEY-265 | I-b/III | Unresectable advanced melanoma | ORR: Approximately 62% in phase I-b; phase III did not confirm benefit | [133,165] |

| Dabrafenib + trametinib + pembrolizumab | KEYNOTE-022 | II | BRAF V600-mutant advanced melanoma | Median PFS: 16.9 months vs 10.7 months | [166] |

| Atezolizumab + vemurafenib + cobimetinib | IMspire150 | III | BRAF V600-mutant advanced melanoma | Median PFS: 15.1 months vs 10.6 months | [167] |

However, acquired resistance remains a central challenge, resulting from complex and multifactorial molecular mechanisms. The BRAF V600E and V600K mutations, for instance, are the main drivers of this neoplasm, promoting constitutive activation of the MEK pathway and being associated with robust yet temporary initial responses, with the V600K variant often correlated with a more aggressive and invasive phenotype[144,148]. This plasticity is strongly conditioned by the transcription factor microphthalmia-associated transcription factor, whose regulation by the MEK pathway defines the balance between proliferative and invasive states, enabling melanoma to rapidly adapt to therapeutic pressure and reestablish itself in the host[144,148,149].

Adaptive resistance to these therapies goes beyond isolated genetic alterations, involving MEK pathway reactivation through cancer osaka thyroid/tumor progression locus 2 amplification and NRAS mutations, in addition to compensatory activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin and DNA repair processes that sustain adaptive expression patterns[144,149]. Alterations in mitochondrial metabolism, with increased oxidative phosphorylation, providing energy to proliferate even under MEK blockade, and activation of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1, regulating growth, protein synthesis, and cellular metabolism, also create a bioenergetic environment favorable to tumor survival despite pharmacological inhibition[143,149]. Added to this are epigenetic changes, such as chromatin remodeling and altered methylation patterns, which prolong a reversible state of treatment tolerance and contribute to intratumoral heterogeneity[144]. These findings highlight that treatment resistance is not merely an intrinsic cellular phenomenon, but a dynamic process that integrates genomic, epigenetic, and metabolic pathways.

Another critical element is the role of the TME, which supports resistance through the secretion of paracrine factors such as TGF-β, hepatocyte growth factor, IL-8, and C-C motif ligand 2 by CAFs and suppressive immune cells (MDSCs and Tregs), favoring the maintenance of the tumor ecosystem[150]. Furthermore, recent studies have identified the androgen receptor as a prominent mediator of resistance to BRAFi/MEKi inhibitors, facilitating tumor proliferation independently of the MEK pathway; its pharmacological inhibition has been shown to restore tumor sensitivity and enhance antitumor efficacy[150,151]. This understanding has driven new therapeutic strategies that combine MEK pathway inhibitors with epigenetic agents, immunotherapies, and TME modulators, aiming to prevent or overcome acquired resistance and achieve more durable clinical responses[143,144,148-151].

Immune-checkpoint blockade therapy, together with agents targeting additional inhibitory receptors such as TIM-3, LAG-3, T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT), and B and T lymphocyte attenuator, has transformed the treatment of several cancer types by promoting durable responses, with melanoma standing out as a notable example. This approach has also been complemented by combinatorial procedures, co-stimulatory receptor activators, and strategies capable of enhancing tumor immunogenicity, such as cancer vaccines, oncolytic viruses, as well as epigenetic and senolytic therapies[152].

Recent advances in pharmacological antineoplastic immunoregulation highlight a promising landscape for the discovery and development of next-generation agents that extend beyond traditional checkpoint inhibitors, including bispecific and multispecific antibodies, epigenetic therapies, and cytokine-based approaches[153]. These modalities expand the therapeutic arsenal by achieving a more refined performance over immunological mechanisms. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that CD4+ T cell-based immunotherapies, when combined with OX40 co-stimulation or even CTLA-4 blockade, are capable of eliminating tumor variants that have lost antigen expression. This effect occurs through a mechanism dependent on neutrophils and nitric oxide production, thereby emphasizing the relevance of cooperation among different immune system components to overcome tumor immune evasion[154]. The stimulation of multiple immune branches has proven essential to prevent such evasion and to promote more effective responses against tumor heterogeneity, underscoring the interdependence between T cells and neutrophils in the eradication of escape variants[154].

With respect to clinical therapies under development, immuno-oncology is rapidly evolving, with agents that act through both the adaptive and innate immune systems to recognize and eliminate tumor cells. Although checkpoint inhibitors were first introduced in 2011, they now rank second in the number of regulatory approvals. Among the classes currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration are: ICIs, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, bispecific T-cell engager antibodies, T cell receptor-based therapy, TILs therapy, cytokine therapy, cancer vaccines, and oncolytic virus therapy[155].

In metastatic melanoma, some patients exhibit a significant initial response to PD-1 blockade, with complete tumor regression observed within the first weeks of treatment, highlighting the power of this strategy to induce durable responses[156]. However, after a period of clinical benefit, acquired resistance may occur, characterized by late tumor progression, as seen in cases where new lesions arise after months of disease control[156]. In such scenarios, the introduction of combined approaches, such as the association of anti-PD-1 with ipilimumab or local radiotherapy, has been shown to restore antitumor responses and prolong survival, reinforcing the importance of adaptive management in the face of resistance[156].

The cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING) axis is a central component linking inflammation to antitumor immunity, particularly in solid tumors. In addition to detecting cytosolic DNA and inducing type I IFNs, cGAS functions as an intracellular sensor capable of transmitting signals to neighboring cells through 2′3′-cGAMP (cyclic GMP-AMP), a messenger that crosses intercellular junctions[157,158]. This function enables DNA damage or cellular stress to trigger a networked immune response, activating dendritic cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes. In cancer, the cGAS-STING pathway is essential both for immune surveillance and for tumor sensitization to immunomodulatory therapies, reprogramming the cellular niche and enhancing pro-immune inflammation[157,158]. It has also been suggested that this pathway regulates cellular metabolism and adaptation to stress, influencing the response to combined therapies[159].

Beyond stimulating adaptive immunity, cGAS-STING interacts with inflammasomes and inflammatory cell death mechanisms such as pyroptosis, establishing a feedback loop that amplifies innate responses[160]. This knowledge has guided the development of pharmacological agonists capable of activating STING in a controlled manner, with both intratumoral and systemic applications via nanotechnology, thereby promoting T cell infiltration, remodeling the TME, and potentially reversing tumor resistance[157,159,161]. Despite challenges related to toxicity, tumor heterogeneity, and escape mechanisms, combinations integrating STING agonists, checkpoint blockade, and inhibition of cGAMP metabolism show promise in enhancing the efficacy of oncology[157,159,161].

Equally noteworthy is the TIGIT receptor as an immune regulator in melanoma resistance. Expressed in CD8+ T cells, Tregs, and NK cells, TIGIT interacts with its ligand CD155 within the tumor ecosystem, suppressing effector T cell activation and promoting immune exhaustion. High expression of TIGIT has been correlated with poor prognosis and resistance to immunotherapy, underscoring its relevance as a therapeutic target. Combining TIGIT blockade with strategies that modulate the cGAS-STING pathway holds potential to restore T cell function and enhance antitumor responses[162].

The immunobiology of melanoma illustrates the intricate interplay between tumor evolution and host immunity. While ICIs and targeted therapies have transformed clinical outcomes, resistance remains a critical barrier. Advances in biomarker discovery, multi-omics profiling, and emerging immunomodulatory strategies provide new opportunities to overcome these limitations. Continued integration of translational research into clinical practice will be essential for achieving durable responses and improving patient survival in melanoma.

| 1. | Khayyati Kohnehshahri M, Sarkesh A, Mohamed Khosroshahi L, HajiEsmailPoor Z, Aghebati-Maleki A, Yousefi M, Aghebati-Maleki L. Current status of skin cancers with a focus on immunology and immunotherapy. Cancer Cell Int. 2023;23:174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Long GV, Swetter SM, Menzies AM, Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA. Cutaneous melanoma. Lancet. 2023;402:485-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 443] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sun Y, Shen Y, Liu Q, Zhang H, Jia L, Chai Y, Jiang H, Wu M, Li Y. Global trends in melanoma burden: A comprehensive analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study, 1990-2021. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025;92:100-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 46.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fried L, Tan A, Bajaj S, Liebman TN, Polsky D, Stein JA. Technological advances for the detection of melanoma: Advances in diagnostic techniques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:983-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang W, Zeng W, Jiang A, He Z, Shen X, Dong X, Feng J, Lu H. Global, regional and national incidence, mortality and disability-adjusted life-years of skin cancers and trend analysis from 1990 to 2019: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Cancer Med. 2021;10:4905-4922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wu Y, Wang Y, Wang L, Yin P, Lin Y, Zhou M. Burden of melanoma in China, 1990-2017: Findings from the 2017 global burden of disease study. Int J Cancer. 2020;147:692-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Berk-Krauss J, Stein JA, Weber J, Polsky D, Geller AC. New Systematic Therapies and Trends in Cutaneous Melanoma Deaths Among US Whites, 1986-2016. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:731-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bolick NL, Geller AC. Epidemiology of Melanoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2021;35:57-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bolick NL, Geller AC. Epidemiology and Screening for Melanoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2024;38:889-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dzwierzynski WW. Melanoma Risk Factors and Prevention. Clin Plast Surg. 2021;48:543-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Olsen CM, Pandeya N, Neale RE, Law MH, Whiteman DC. Phenotypic and genotypic risk factors for invasive melanoma by sex and body site. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:914-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lynch HT, Fusaro RM, Pester J, Lynch JF. Familial atypical multiple mole melanoma (FAMMM) syndrome: genetic heterogeneity and malignant melanoma. Br J Cancer. 1980;42:58-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Correya T, Duncan Z, Garcia N, Amu-Nnadi C, Broman K. Incidence and Risk Factors for Incidental Cancer on Melanoma Wide Excisions. J Surg Res. 2023;284:24-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Huang J, Chan SC, Ko S, Lok V, Zhang L, Lin X, Lucero-Prisno Iii DE, Xu W, Zheng ZJ, Elcarte E, Withers M, Wong MCS. Global Incidence, Mortality, Risk Factors and Trends of Melanoma: A Systematic Analysis of Registries. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:965-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Arnold M, Singh D, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Vaccarella S, Meheus F, Cust AE, de Vries E, Whiteman DC, Bray F. Global Burden of Cutaneous Melanoma in 2020 and Projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:495-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in RCA: 800] [Article Influence: 200.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Eddy K, Chen S. Overcoming Immune Evasion in Melanoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:8984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kalaora S, Nagler A, Wargo JA, Samuels Y. Mechanisms of immune activation and regulation: lessons from melanoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22:195-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 42.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cui C, Ott PA, Wu CJ. Advances in Vaccines for Melanoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2024;38:1045-1060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tímár J, Ladányi A. Molecular Pathology of Skin Melanoma: Epidemiology, Differential Diagnostics, Prognosis and Therapy Prediction. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:5384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ohta S, Misawa A, Kyi-Tha-Thu C, Matsumoto N, Hirose Y, Kawakami Y. Melanoma antigens recognized by T cells and their use for immunotherapy. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32:297-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | McGrail DJ, Pilié PG, Rashid NU, Voorwerk L, Slagter M, Kok M, Jonasch E, Khasraw M, Heimberger AB, Lim B, Ueno NT, Litton JK, Ferrarotto R, Chang JT, Moulder SL, Lin SY. High tumor mutation burden fails to predict immune checkpoint blockade response across all cancer types. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:661-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 813] [Article Influence: 162.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jhunjhunwala S, Hammer C, Delamarre L. Antigen presentation in cancer: insights into tumour immunogenicity and immune evasion. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21:298-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 1002] [Article Influence: 200.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kalaora S, Wolf Y, Feferman T, Barnea E, Greenstein E, Reshef D, Tirosh I, Reuben A, Patkar S, Levy R, Quinkhardt J, Omokoko T, Qutob N, Golani O, Zhang J, Mao X, Song X, Bernatchez C, Haymaker C, Forget MA, Creasy C, Greenberg P, Carter BW, Cooper ZA, Rosenberg SA, Lotem M, Sahin U, Shakhar G, Ruppin E, Wargo JA, Friedman N, Admon A, Samuels Y. Combined Analysis of Antigen Presentation and T-cell Recognition Reveals Restricted Immune Responses in Melanoma. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1366-1375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Peri A, Greenstein E, Alon M, Pai JA, Dingjan T, Reich-Zeliger S, Barnea E, Barbolin C, Levy R, Arnedo-Pac C, Kalaora S, Dassa B, Feldmesser E, Shang P, Greenberg P, Levin Y, Benedek G, Levesque MP, Adams DJ, Lotem M, Wilmott JS, Scolyer RA, Jönsson GB, Admon A, Rosenberg SA, Cohen CJ, Niv MY, Lopez-Bigas N, Satpathy AT, Friedman N, Samuels Y. Combined presentation and immunogenicity analysis reveals a recurrent RAS.Q61K neoantigen in melanoma. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e129466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhou Q, Yan Y, Li Y, Fu H, Lu D, Li Z, Wang Y, Wang J, Zhu H, Ren J, Luo H, Tao M, Cao Y, Wei S, Fan S. Tumor-derived extracellular vesicles in melanoma immune response and immunotherapy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;156:113790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kumar P, Boyne C, Brown S, Qureshi A, Thorpe P, Synowsky SA, Shirran S, Powis SJ. Tumour-associated antigenic peptides are present in the HLA class I ligandome of cancer cell line derived extracellular vesicles. Immunology. 2022;166:249-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Li J, Li J, Peng Y, Du Y, Yang Z, Qi X. Dendritic cell derived exosomes loaded neoantigens for personalized cancer immunotherapies. J Control Release. 2023;353:423-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ascic E, Åkerström F, Sreekumar Nair M, Rosa A, Kurochkin I, Zimmermannova O, Catena X, Rotankova N, Veser C, Rudnik M, Ballocci T, Schärer T, Huang X, de Rosa Torres M, Renaud E, Velasco Santiago M, Met Ö, Askmyr D, Lindstedt M, Greiff L, Ligeon LA, Agarkova I, Svane IM, Pires CF, Rosa FF, Pereira CF. In vivo dendritic cell reprogramming for cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2024;386:eadn9083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Patton EE, Mueller KL, Adams DJ, Anandasabapathy N, Aplin AE, Bertolotto C, Bosenberg M, Ceol CJ, Burd CE, Chi P, Herlyn M, Holmen SL, Karreth FA, Kaufman CK, Khan S, Kobold S, Leucci E, Levy C, Lombard DB, Lund AW, Marie KL, Marine JC, Marais R, McMahon M, Robles-Espinoza CD, Ronai ZA, Samuels Y, Soengas MS, Villanueva J, Weeraratna AT, White RM, Yeh I, Zhu J, Zon LI, Hurlbert MS, Merlino G. Melanoma models for the next generation of therapies. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:610-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Marzagalli M, Ebelt ND, Manuel ER. Unraveling the crosstalk between melanoma and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Semin Cancer Biol. 2019;59:236-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 269] [Article Influence: 38.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Harel M, Ortenberg R, Varanasi SK, Mangalhara KC, Mardamshina M, Markovits E, Baruch EN, Tripple V, Arama-Chayoth M, Greenberg E, Shenoy A, Ayasun R, Knafo N, Xu S, Anafi L, Yanovich-Arad G, Barnabas GD, Ashkenazi S, Besser MJ, Schachter J, Bosenberg M, Shadel GS, Barshack I, Kaech SM, Markel G, Geiger T. Proteomics of Melanoma Response to Immunotherapy Reveals Mitochondrial Dependence. Cell. 2019;179:236-250.e18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Veatch JR, Lee SM, Shasha C, Singhi N, Szeto JL, Moshiri AS, Kim TS, Smythe K, Kong P, Fitzgibbon M, Jesernig B, Bhatia S, Tykodi SS, Hall ET, Byrd DR, Thompson JA, Pillarisetty VG, Duhen T, McGarry Houghton A, Newell E, Gottardo R, Riddell SR. Neoantigen-specific CD4(+) T cells in human melanoma have diverse differentiation states and correlate with CD8(+) T cell, macrophage, and B cell function. Cancer Cell. 2022;40:393-409.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lauss M, Phung B, Borch TH, Harbst K, Kaminska K, Ebbesson A, Hedenfalk I, Yuan J, Nielsen K, Ingvar C, Carneiro A, Isaksson K, Pietras K, Svane IM, Donia M, Jönsson G. Molecular patterns of resistance to immune checkpoint blockade in melanoma. Nat Commun. 2024;15:3075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Pozniak J, Pedri D, Landeloos E, Van Herck Y, Antoranz A, Vanwynsberghe L, Nowosad A, Roda N, Makhzami S, Bervoets G, Maciel LF, Pulido-Vicuña CA, Pollaris L, Seurinck R, Zhao F, Flem-Karlsen K, Damsky W, Chen L, Karagianni D, Cinque S, Kint S, Vandereyken K, Rombaut B, Voet T, Vernaillen F, Annaert W, Lambrechts D, Boecxstaens V, Saeys Y, van den Oord J, Bosisio F, Karras P, Shain AH, Bosenberg M, Leucci E, Paschen A, Rambow F, Bechter O, Marine JC. A TCF4-dependent gene regulatory network confers resistance to immunotherapy in melanoma. Cell. 2024;187:166-183.e25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 58.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Trocchia M, Ventrici A, Modestino L, Cristinziano L, Ferrara AL, Palestra F, Loffredo S, Capone M, Madonna G, Romanelli M, Ascierto PA, Galdiero MR. Innate Immune Cells in Melanoma: Implications for Immunotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:8523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Wang C, Barnoud C, Cenerenti M, Sun M, Caffa I, Kizil B, Bill R, Liu Y, Pick R, Garnier L, Gkountidi OA, Ince LM, Holtkamp S, Fournier N, Michielin O, Speiser DE, Hugues S, Nencioni A, Pittet MJ, Jandus C, Scheiermann C. Dendritic cells direct circadian anti-tumour immune responses. Nature. 2023;614:136-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 51.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sikorski H, Żmijewski MA, Piotrowska A. Tumor Microenvironment in Melanoma-Characteristic and Clinical Implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:6778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Amalinei C, Grigoraș A, Lozneanu L, Căruntu ID, Giușcă SE, Balan RA. The Interplay between Tumour Microenvironment Components in Malignant Melanoma. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58:365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Hendrix MJC, Seftor EA, Margaryan NV, Seftor REB. Heterogeneity and Plasticity of Melanoma: Challenges of Current Therapies. In: Cutaneous Melanoma: Etiology and Therapy [Internet]. Brisbane (AU): Codon Publications; 2017-Dec-21. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Zhang H, Yue X, Chen Z, Liu C, Wu W, Zhang N, Liu Z, Yang L, Jiang Q, Cheng Q, Luo P, Liu G. Define cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in the tumor microenvironment: new opportunities in cancer immunotherapy and advances in clinical trials. Mol Cancer. 2023;22:159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 95.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Avagliano A, Arcucci A. Insights into Melanoma Fibroblast Populations and Therapeutic Strategy Perspectives: Friends or Foes? Curr Med Chem. 2022;29:6159-6168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Chhabra Y, Fane ME, Pramod S, Hüser L, Zabransky DJ, Wang V, Dixit A, Zhao R, Kumah E, Brezka ML, Truskowski K, Nandi A, Marino-Bravante GE, Carey AE, Gour N, Maranto DA, Rocha MR, Harper EI, Ruiz J, Lipson EJ, Jaffee EM, Bibee K, Sunshine JC, Ji H, Weeraratna AT. Sex-dependent effects in the aged melanoma tumor microenvironment influence invasion and resistance to targeted therapy. Cell. 2024;187:6016-6034.e25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Papaccio F, Kovacs D, Bellei B, Caputo S, Migliano E, Cota C, Picardo M. Profiling Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Melanoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:7255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Forsthuber A, Aschenbrenner B, Korosec A, Jacob T, Annusver K, Krajic N, Kholodniuk D, Frech S, Zhu S, Purkhauser K, Lipp K, Werner F, Nguyen V, Griss J, Bauer W, Soler Cardona A, Weber B, Weninger W, Gesslbauer B, Staud C, Nedomansky J, Radtke C, Wagner SN, Petzelbauer P, Kasper M, Lichtenberger BM. Cancer-associated fibroblast subtypes modulate the tumor-immune microenvironment and are associated with skin cancer malignancy. Nat Commun. 2024;15:9678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |