Published online Jan 24, 2026. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v17.i1.114369

Revised: October 26, 2025

Accepted: November 25, 2025

Published online: January 24, 2026

Processing time: 125 Days and 16.7 Hours

Adult sacrococcygeal teratoma (SCT) is extremely rare in clinical practice, with most cases manifesting as mature cystic types. Given the scarcity of clinical studies and literature on this topic, standardized surgical guidelines for adults are notably absent, and current treatment strategies are predominantly derived from pediatric surgical practices. Furthermore, data on surgical outcomes and risk factors for postoperative dysfunction or recurrence in adult patients remain li

To assess surgical outcomes and identify risk factors for dysfunction and recurrence in adult mature cystic SCTs.

We conducted a retrospective analysis of 64 adult patients with mature cystic SCT who received surgical treatment at Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, from January 2005 to December 2020, en

The study incorporated 64 patients, all of whom had been pathologically confirmed to have mature cystic SCTs. The clinical efficacy in adult mature cystic SCTs was not significantly impacted by the various surgical approaches employed. Maximum tumor diameter of 10 cm or more, Altman classification of type III/IV, and intraoperative blood loss of 400 mL or greater were risk factors for postoperative dysfunction (anorectal dysfunction, urinary dysfunction and lower extremity motor dysfunction). The sacrococcyx being left unresected was determined to be an independent risk factor for tumor recurrence.

Surgical approach does not affect outcomes; larger tumors, advanced Altman type, blood loss, and unresected sacrococcyx increase risks of dysfunction and recurrence.

Core Tip: This retrospective study investigates adult mature cystic sacrococcygeal teratomas, a rare entity often lacking standardized treatment guidelines. Among 64 surgically treated patients, tumor size ≥ 10 cm, Altman type III/IV, and blood loss ≥ 400 mL are identified as independent risk factors for postoperative dysfunction. Failure to resect the sacrococcyx significantly increases recurrence risk. Notably, surgical approach does not affect outcomes. These findings offer important guidance for individualized surgical planning and functional preservation in this uncommon but clinically challenging tumor.

- Citation: Wang Y, Wang Z, Tang YC, Li Y, Guo XB. Mature cystic sacrococcygeal teratoma in adults: A single-center study. World J Clin Oncol 2026; 17(1): 114369

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v17/i1/114369.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v17.i1.114369

Adult sacrococcygeal teratoma (SCT) is recognized as a congenital tumor and ranks among the most common extragonadal germ cell tumors, typically arising from Hensen’s node in the sacrococcygeal region[1]. The majority of cases are diagnosed at birth or in childhood, while a small proportion remains asymptomatic until adulthood, when tumor growth triggers clinical symptoms. Despite the sacrococcygeal region being a common extragonadal location for teratomas, adult SCT is exceedingly uncommon, with an incidence estimated at approximately 1 in 40000 to 1 in 63000, and a male-to-female ratio of 1:3[2]. SCTs are categorized as mature, immature, or malignant, depending on tissue type and differentiation level. While the majority are benign, about 1% to 2% may undergo malignant transformation[3]. Although mature cystic SCTs are generally benign, they have the potential to recur many years post-resection, with such recurrences carrying a risk of malignancy[4-6]. The average recurrence rates are 10% for mature SCTs, 33% for immature SCTs, and 18% for malignant SCTs[7].

Surgical resection stands as the cornerstone of treatment for adult SCT. However, given the tumor’s close anatomical relationship with the rectum, anal sphincter, and pelvic neurovascular structures, patients are prone to long-term complications, such as anorectal dysfunction, urinary dysfunction, and lower limb motor deficits[8,9]. Thus, safeguarding anal and bladder function during surgical procedures is of paramount importance to gastrointestinal and oncologic surgeons. Surgical approaches include transabdominal, transsacral, or combined techniques, but standardized diagnostic and therapeutic protocols for adult SCT are currently lacking[10].

Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for adult SCT predominantly draw from pediatric case experiences, but adult SCT exhibits distinct characteristics in growth patterns, surgical risks, and functional outcomes compared to its pediatric counterpart. Owing to the rarity of adult SCT, comprehensive clinical data are scarce, leaving key areas, such as surgical technique selection, sacrococcygeal management, and functional preservation, without robust guidance. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the safety and efficacy of various surgical approaches for mature cystic SCT in adults and to identify risk factors contributing to postoperative dysfunction and tumor recurrence, with the goal of providing evidence-based recommendations for clinical practice.

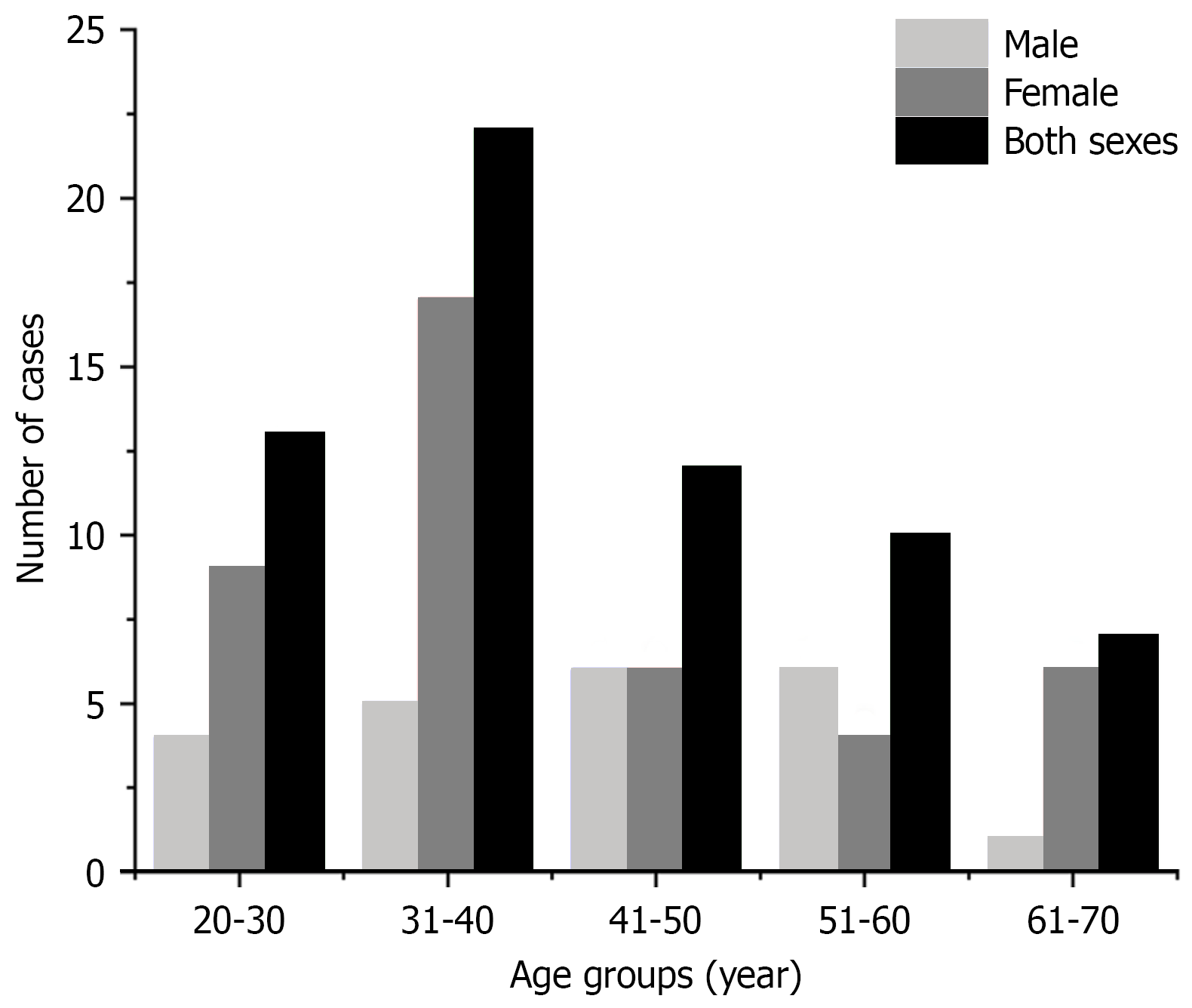

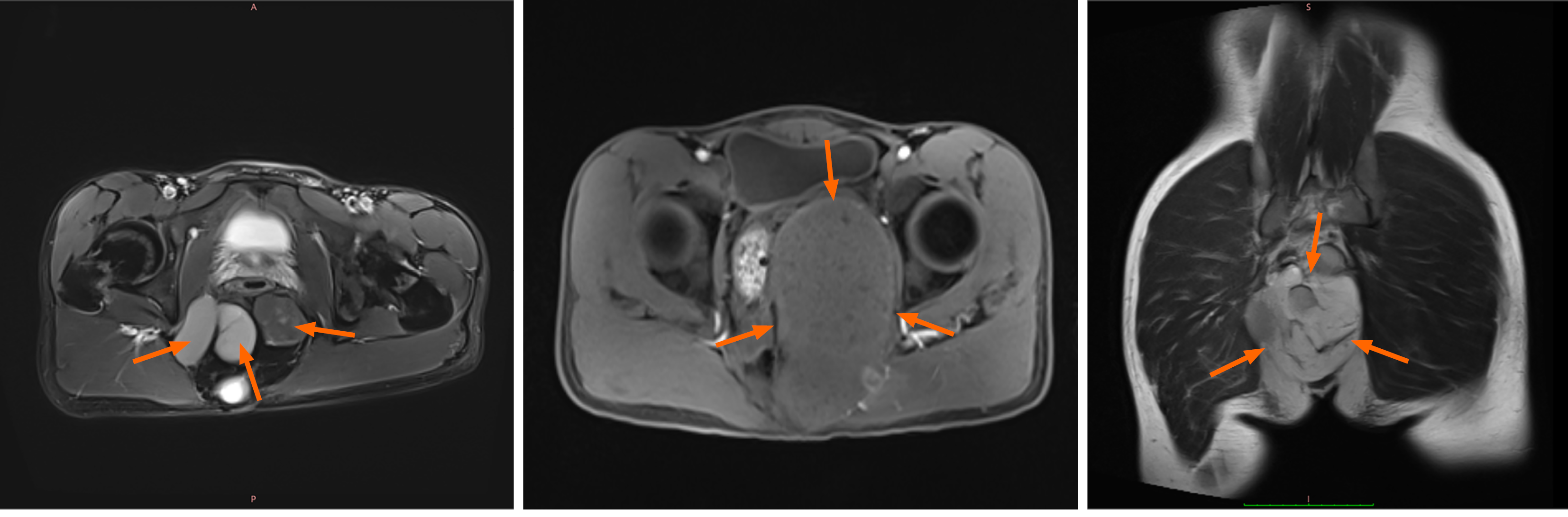

Clinical data were gathered from 64 adult patients with mature cystic SCT who received treatment at Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, from January 2005 to December 2020. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients diagnosed at or after 18 years of age; (2) Confirmed diagnosis of mature cystic SCT via postoperative pathology; (3) Surgical resection performed at our institution; and (4) Availability of complete clinical, surgical, pathological, and follow-up data. Patients were excluded if they had: (1) Histologically confirmed immature or malignant teratoma at initial diagnosis; (2) Incomplete medical records or were lost to follow-up; (3) Not undergo surgery; and (4) Other coexisting malignancies or severe systemic diseases affecting survival or functional assessment. The study cohort comprised 22 males (34.4%) and 42 females (65.6%), with a median age of 38 years (range: 22-68) and a median body mass index of 23.65 kg/m² (range: 16.8-31.5) (Figure 1). Surgical approaches included laparoscopic-assisted anterior approach (Type A) for 13 patients, posterior approach (Type B) for 22 patients, and combined laparoscopic-posterior approach (Type C) for 29 patients. Preoperative pelvic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was conducted for all patients, revealing presacral space-occupying lesions (Figure 2).

We systematically evaluated patient demographics, surgical strategies, intraoperative blood loss (≥ 400 mL), sacrococcygeal resection status, Altman classification, tumor size, pathological diagnosis, short-term complications, such as sacrococcygeal wound necrosis and intestinal fistula, functional impairments (anorectal, urinary, lower limb motor dysfunction), and tumor recurrence. Postoperative functional outcomes were assessed based on Masahata et al’s criteria[9]. Bowel function was stratified into five levels: 0 (normal bowel movements), 1 (fecal incontinence), 2 (soiling), 3 (constipation requiring laxatives/enemas), and 4 (severe constipation necessitating bowel irrigation or manual extraction). Patients scoring 1-4 were classified as having anorectal dysfunction. Urinary function followed a similar five-tier system: 0 (normal urination), 1 (incontinence), 2 (recurrent urinary tract infections), 3 (neurogenic bladder), and 4 (clean intermittent catheterization). Scores of 1-4 indicated urinary dysfunction. Lower limb motor function was categorized into three grades: 0 (normal function), 1 (limping), and 2 (walking difficulty), with grades 1-2 denoting motor dysfunction.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0. To assess differences in excessive intraoperative blood loss (≥ 400 mL), sacrococcygeal wound necrosis, intestinal fistula formation, functional impairments, and tumor recurrence across the three surgical approaches, Fisher’s exact test was applied. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were employed to identify independent risk factors for functional disorders and tumor recurrence. Continuous variables are reported as medians with interquartile ranges, while categorical data are presented as frequencies with percentages, accompanied by 95%CI for proportions. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

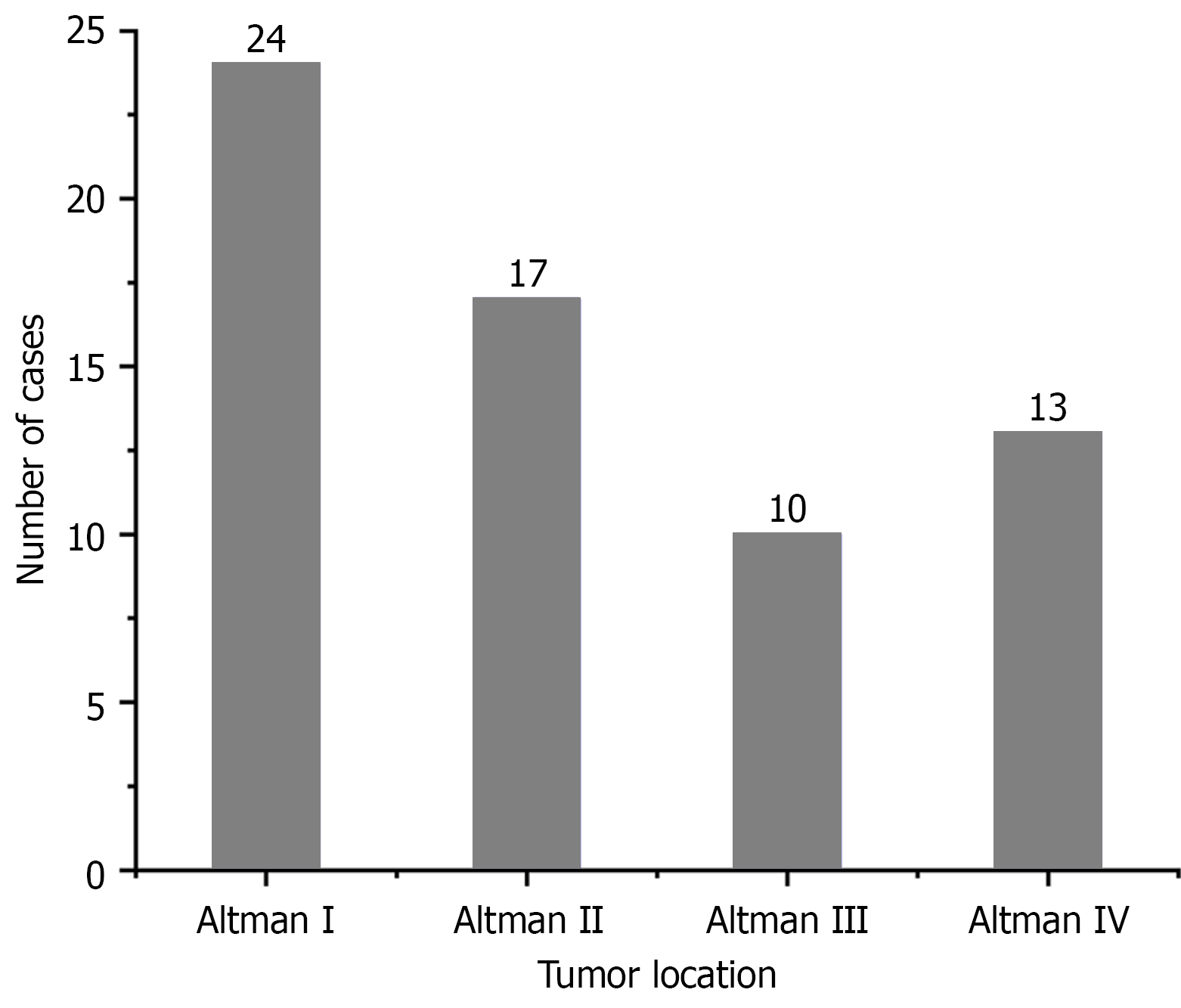

All patients underwent complete surgical resection, with postoperative pathology confirming mature cystic teratoma in each case. Surgical approaches included Type A in 13 patients, Type B in 22 patients, and Type C in 29 patients. The median maximum tumor diameter measured 10.85 cm (range: 3.3-23.5). According to the Altman classification system, 41 cases (64.1%) were classified as Type I/II, while 23 cases (35.9%) fell into Type III/IV (Figure 3). Sacrococcygeal resection was omitted in 21 patients, comprising 13 from the Type A group, 2 from Type B, and 6 from Type C.

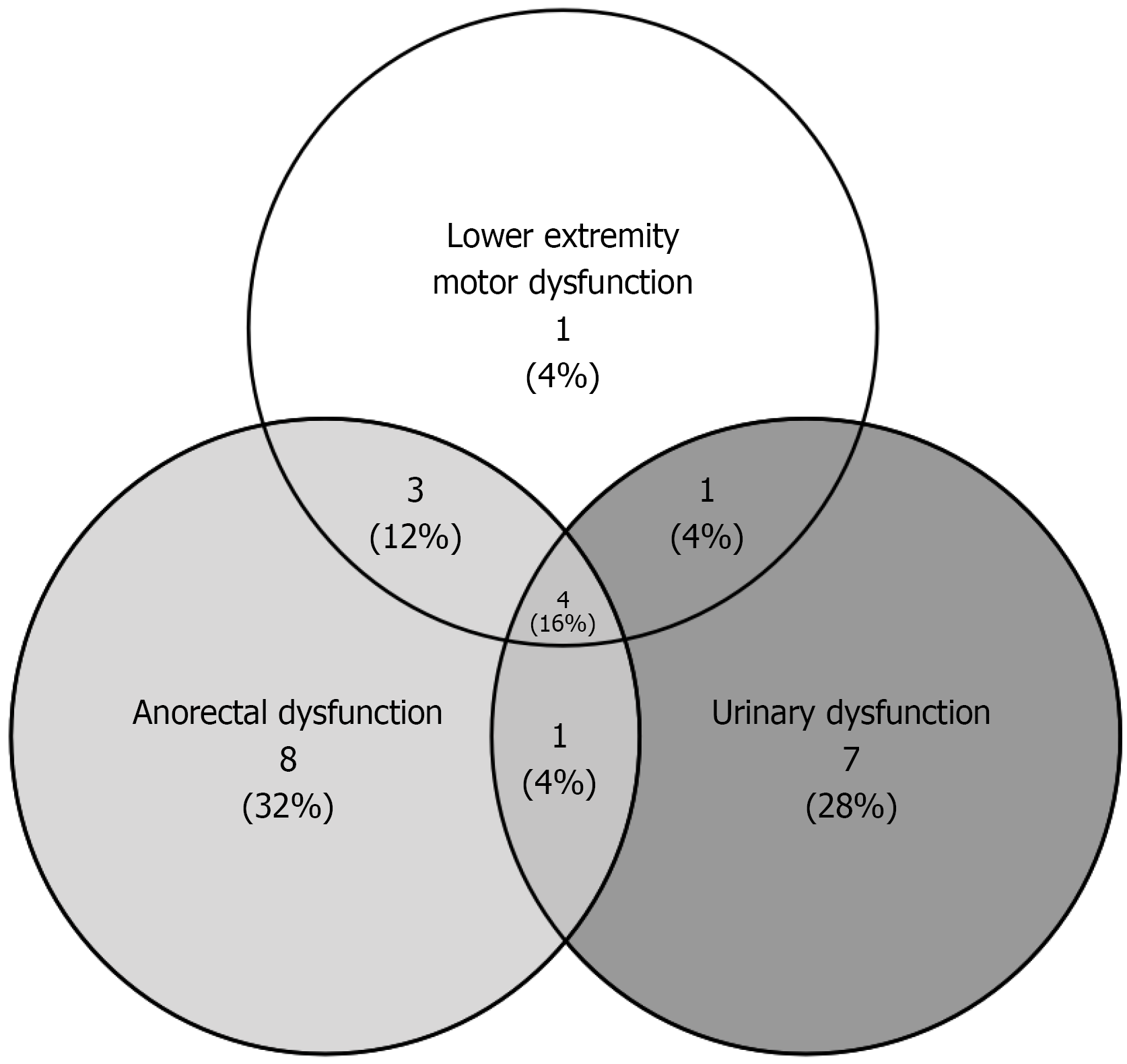

Postoperative complications comprised sacrococcygeal wound necrosis (15 patients) and intestinal fistula (5 patients). Functional impairments included anorectal dysfunction (16 patients), urinary dysfunction (13 patients), and lower limb motor dysfunction (9 patients), with overlapping symptoms noted in some cases (Figure 4). Tumor recurrence occurred in 16 patients, including one malignant transformation necessitating chemotherapy. Detailed clinical parameters are presented in Table 1. The interval of the 16 patients with recurrence is shown in Table 2.

| Clinical parameters | Variable |

| Total number of patients | 64 (100) |

| Sex; female | 42 (65.6) |

| Age (year) | 38 (22-68) |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (range) | 23.65 (16.8-31.5) |

| Hypertension | 12 (18.8) |

| Diabetes | 14 (21.9) |

| History of abdominal surgery | 8 (12.5) |

| Maximum tumor diameter (cm), median (range) | 10.85 (3.3-23.5) |

| Altman’ classification | |

| I-II | 41 (64.1) |

| III/IV | 23 (35.9) |

| Pathology | |

| Mature | 64 (100) |

| Surgical approach | |

| Type A | 13 (20.3) |

| Type B | 22 (34.4) |

| Type C | 29 (45.3) |

| Sacrococcygeal resection | 43 (67.2) |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | |

| ≥ 400 mL | 7 (10.9) |

| Sacrococcygeal incision necrosis | 15 (23.4) |

| Intestinal fistula | 5 (7.8) |

| Anorectal dysfunction | 16 (25.0) |

| Urinary dysfunction | 13 (20.3) |

| Lower limb motor dysfuction | 9 (14.1) |

| Reccurence of tumor | |

| Benign | 15 (23.4) |

| Malignancy | 1 (1.6) |

| Patients with recurrence | Recurrence period (months) |

| 1 | 36 |

| 2 | 66 |

| 3 | 28.8 |

| 4 | 37.2 |

| 5 | 18 |

| 6 | 10.8 |

| 7 | 62.4 |

| 8 | 43.2 |

| 9 | 91.2 |

| 10 | 15.6 |

| 11 | 31.2 |

| 12 | 21.6 |

| 13 | 13.2 |

| 14 | 25.2 |

| 15 | 30 |

| 16 | 8.4 |

Statistical analysis demonstrated no statistically significant differences across the three surgical approaches in terms of excessive intraoperative blood loss (≥ 400 mL), sacrococcygeal resection rates, wound necrosis, intestinal fistula formation, functional impairments, or tumor recurrence (all P > 0.05) (Table 3).

| Variables | Type A (n = 13) | Type B (n = 22) | Type C (n = 29) | P value |

| Intraoperative blood loss ≥ 400 mL | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0.767 |

| Sacrococcygeal incision necrosis | - | 8 | 7 | 0.371 |

| Intestinal fistula | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0.165 |

| Anorectal dysfunction | 4 | 4 | 8 | 0.655 |

| Urinary dysfunction | 5 | 3 | 5 | 0.218 |

| Lower limb motor dysfuction | 3 | 1 | 5 | 0.240 |

| Reccurence of tumor | 6 | 3 | 7 | 0.108 |

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses identified two consistent risk factors for both anorectal and urinary dysfunction: Maximum tumor diameter of 10 cm or more and Altman classification III/IV (Tables 4 and 5). Lower limb motor dysfunction demonstrated distinct associations, being significantly linked to Altman classification III/IV and intraoperative blood loss of 400 mL or more, but showing no correlation with tumor size (Table 6).

| Variables | Univariable | Multivariable | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Sex; female | Yes | 1.800 (0.504-6.432) | 0.366 | ||

| Age ≥ 40 (year) | Yes | 0.600 (0.188-1.913) | 0.388 | ||

| BMI ≥ 25 (kg/m2) | Yes | 0.916 (0.285-2.938) | 0.882 | ||

| Hypertension | Yes | 1.000 (0.235-4.261) | 1.000 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | Yes | 0.897 (0.245-3.288) | 0.870 | ||

| History of abdominal surgery | Yes | 1.000 (0.181-5.533) | 1.000 | ||

| Maximum tumor diameter ≥ 10 (cm) | Yes | 3.545 (1.000-12.575) | 0.050a | 8.068 (1.648-39.491) | 0.010a |

| Altman’ classification | III/IV vs I-II | 4.487 (1.357-14.834) | 0.014a | 9.484 (2.103-42.774) | 0.033a |

| Surgical approach | Type A | 1 | |||

| Type B | 0.500 (0.101-2.477) | 0.396 | |||

| Type C | 0.857 (0.205-3.589) | 0.833 | |||

| Sacrococcygeal resection | Yes | 0.529 (0.165-1.701) | 0.286 | ||

| Intraoperative blood loss ≥ 400 (mL) | Yes | 5.000 (0.983-25.437) | 0.052 | ||

| Variables | Univariable | Multivariable | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Sex; female | Yes | 0.800 (0.227-2.820 | 0.728 | ||

| Age ≥ 40 (year) | Yes | 0.964 (0.284-3.270) | 0.953 | ||

| BMI ≥ 25 (kg/m2) | Yes | 0.221 (0.044-1.101) | 0.065 | ||

| Hypertension | Yes | 0.303 (0.035-2.592) | 0.276 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | Yes | 2.301 (0.558-7.388) | 0.282 | ||

| History of abdominal surgery | Yes | 1.364 (0.242-7.698) | 0.725 | ||

| Maximum tumor diameter ≥ 10 (cm) | Yes | 3.750 (0.922-15.245) | 0.065a | 9.622 (1.694-54.663) | 0.011a |

| Altman’ classification | III/IV vs I-II | 5.946 (1.575-22.454) | 0.009a | 13.264 (2.581-68.168) | 0.002a |

| Surgical approach | Type A | 1.000 | |||

| Type B | 0.253 (0.048-1.319) | 0.103 | |||

| Type C | 0.333 (0.076-1.458) | 0.144 | |||

| Sacrococcygeal resection | Yes | 0.731 (0.207-2.590) | 0.628 | ||

| Intraoperative blood loss ≥ 400 (mL) | Yes | 1.673 (0.286-9.789) | 0.568 | ||

| Variables | Univariable | Multivariable | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Sex; female | Yes | 2.000 (0.378-10.569) | 0.414 | ||

| Age ≥ 40 (year) | Yes | 0.519 (0.118-2.285) | 0.385 | ||

| BMI ≥ 25 (kg/m2) | Yes | 0.398 (0.076-2.091) | 0.276 | ||

| Hypertension | Yes | 0.500 (0.056-4.429) | 0.533 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | Yes | 0.305 (0.035-2.639) | 0.281 | ||

| History of abdominal surgery | Yes | 0.857 (0.093-7.931) | 0.892 | ||

| Maximum tumor diameter ≥ 10 (cm) | Yes | 1.929 (0.438-8.500) | 0.385 | ||

| Altman’ classification | III/IV vs I-II | 8.531 (1.597-45.580) | 0.012a | 16.792 (1.847-152.666) | 0.012a |

| Surgical approach | Type A | 1.000 | |||

| Type B | 0.159 (0.015-1.724) | 0.130 | |||

| Type C | 0.694 (0.139-3.475) | 0.657 | |||

| Sacrococcygeal resection | Yes | 0.559 (0.133-2.346) | 0.427 | ||

| Intraoperative blood loss ≥ 400 (mL) | Yes | 6.375 (1.142-35.581) | 0.035a | 17.366 (1.490-202.372) | 0.023a |

Among the 64 patients, 16 developed postoperative recurrence, including 11 who had not undergone sacrococcygeal resection. One case progressed to malignant recurrence requiring chemotherapy, while the remaining 15 recurrent patients underwent reoperation, with postoperative pathology confirming mature teratomas in all cases. Multivariate logistic regression identified failure to resect the sacrococcygeal region as an independent risk factor for recurrence (Table 7). In our cohort, recurrence rates differed among the three surgical approaches: 46.2% (6/13) in the laparoscopic-assisted anterior approach (Type A), 13.6% (3/22) in the posterior approach (Type B), and 24.1% (7/29) in the combined laparoscopic-posterior approach (Type C). Notably, higher recurrence rates in Type A were largely attributable to the omission of coccygectomy in all 13 patients, rather than the surgical approach itself. There was no statistically significant difference in recurrence rate between the different surgical procedures (P = 0.108). These findings suggest that coccygeal resection, rather than the choice of surgical approach, plays a decisive role in minimizing recurrence risk.

| Variables | Univariable | Multivariable | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Sex; female | Yes | 1.206 (0.359-4.051) | 0.761 | ||

| Age ≥ 40 (year) | Yes | 1.653 (0.528-5.171) | 0.388 | ||

| BMI ≥ 25 (kg/m2) | Yes | 1.296 (0.411-4.084) | 0.658 | ||

| Hypertension | Yes | 0.543 (0.106-2.791) | 0.465 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | Yes | 2.018 (0.599-6.805) | 0.258 | ||

| History of abdominal surgery | Yes | 1.000 (0.181-5.533) | 1.000 | ||

| Maximum tumor diameter ≥ 10 (cm) | Yes | 1.183 (0.379-3.693) | 0.773 | ||

| Altman’ classification | III/IV vs I-II | 2.200 (0.693-6.979) | 0.181 | ||

| Surgical approach | Type A | 1.000 | |||

| Type B | 0.184 (0.036-0.944) | 0.043a | |||

| Type C | 0.371 (0.093-1.480) | 0.160 | |||

| Sacrococcygeal resection | Yes | 0.120 (0.034-0.424) | 0.001a | 0.084 (0.015-0.475) | 0.005a |

| Intraoperative blood loss ≥ 400 (mL) | Yes | 1.229 (0.214-7.050) | 0.817 | ||

Most mature cystic SCTs in adults go undetected during childhood. In adulthood, these tumors generally exhibit progressive growth, frequently manifesting as compression symptoms or an asymmetrical sacrococcygeal mass discovered during physical examination. Some patients may also report abdominal pain and distension[11]. A portion of adult SCT cases are recurrent teratomas. SCTs are categorized into four types based on their location[12]: Type I (46%) is entirely extra-pelvic; Type II (35%) is predominantly extra-pelvic with minor pelvic extension; Type III (9%) is mainly pelvic with a minor extra-pelvic component; and Type IV (10%) is entirely within the pelvis. SCTs can be cystic, solid, or a combination of both. Histologically, they are categorized as mature, immature, mixed, or malignant teratomas. Mature teratomas are commonly cystic and fatty, with minimal solid tissue[12]. They are usually benign, and their cysts may contain sebaceous material, keratin, hair, bone, or other tissues. The risk of malignant transformation in mature cystic teratomas ranges from 0.2% to 2%. The overall SCT-related mortality was 3%[13]. Complete surgical resection is the mainstay of SCT treatment[14]. The surgical approach is determined by tumor size, location, degree of local invasion, and the surgeon’s experience. Preoperative computed tomography and MRI scans are crucial for mapping tumor anatomy, vascular involvement, and its relationship to nearby structures, especially the sacrococcygeal bone, which aids in selecting the best surgical strategy[15].

Incomplete resection, tumor spillage, and a retained coccyx are significant risk factors for SCT recurrence[16]. While the necessity of coccyx removal is debated, both the authors’ clinical experience and existing literature advocate for coccyx or sacrococcyx resection whenever possible[17,18]. The tumor recurrence rate in this study stood at 25%, with the unresected sacrococcyx emerging as the sole independent risk factor. This finding corroborates earlier research suggesting that the coccyx may harbor residual tumor cells, contributing to recurrence. In our cohort, sacrococcygeal resection was omitted in 21 patients, primarily during the earlier years of the study period (2005-2010), when standardized guidelines for adult SCT management were lacking. In these cases, surgeons tended to preserve the coccyx if the tumor was cystic, well-circumscribed, and demonstrated no obvious adhesion to the coccyx intraoperatively. Additionally, a few patients requested coccyx preservation due to concerns about postoperative pain and functional impairment. However, based on accumulating evidence, including our current findings, we now strongly recommend routine coccygeal resection whenever feasible, as unresected sacrococcyx heightens the risk of residual tumor cell proliferation and subsequent recurrence, even in benign mature cystic SCTs. Importantly, removing the coccyx or part of the sacrum does not substantially impair postoperative quality of life, whereas coccyx retention may impose physical, psychological, and financial strains due to the potential for recurrence. Most existing evidence regarding the role of coccygectomy originates from pediatric SCT studies, while comprehensive data on adult cases remain scarce. Our findings provide additional support for coccyx resection in adult SCT, demonstrating that omission of coccygectomy was an risk factor for tumor recurrence. Although evidence from pediatric literature guided our early surgical strategies, our results extend these observations to adult patients and underscore the necessity of coccyx removal whenever anatomically feasible.

The posterior approach is well-suited for low-lying sacrococcygeal tumors, providing a more straightforward path, easier access, better visualization, and a lower risk of bowel injury compared to the transabdominal route. However, it has drawbacks such as the potential for uncontrolled pelvic vessel bleeding, pelvic nerve injury, and limited operative space. And posterior approaches were associated with higher rates of sacrococcygeal wound necrosis (8/22, 36.4%) due to larger incisions and poorer local vascularity. However, laparoscopic ligation of the median sacral artery before posterior sagittal resection of type I SCTs has been shown to effectively minimize hemorrhagic risks[19]. With the progress and increasing adoption of laparoscopic techniques, the anterior (transabdominal laparoscopy-assisted) approach offers distinct advantages. Enhanced visualization enables precise dissection and clearer separation of the cystic mass from the rectum in the confined pelvic space, thereby reducing postoperative pain and wound infection risks[20]. This approach is particularly beneficial for patients with a narrow pelvis or obesity, though it does carry an inherent risk of bowel injury.

This study demonstrated no notable differences in intraoperative blood loss, postoperative complications, functional impairment, or tumor recurrence across three surgical approaches, namely, Type A, Type B, and Type C. These results indicate that surgical technique selection should hinge on tumor location, size, and pelvic adhesion status, rather than favoring one specific approach. Notably, the combined approach enhances visualization and better preserves nerve in deeply situated Altman type III/IV tumors, though it involves a trade-off between increased surgical complexity and potential postoperative risks.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that a maximum tumor diameter of 10 cm or more and Altman type III/IV classification are independent risk factors for postoperative anorectal and urinary dysfunction. This is likely due to the technical difficulties associated with large tumors and their deep pelvic location, which increases the risk of pelvic nerve and sphincter damage. Lower limb motor dysfunction was linked to both Altman type III/IV classification and intraoperative blood loss of 400 mL or more. Although no published studies have directly connected excessive intraoperative blood loss to motor dysfunction, we hypothesize that significant blood loss may lead to nerve injury, a blurred surgical field, or increased surgical complexity, potentially explaining the observed association. Furthermore, severe bleeding might indicate tumor invasion into deep nerves and vessels, highlighting the importance of careful intraoperative nerve preservation. However, the small sample size may introduce bias, necessitating further validation through larger prospective studies.

Reported rates of bowel dysfunction after SCT resection range widely, from 7% to 60%[21]. Fortunately, functional symptoms often improve or resolve over time[22,23]. Therefore, adopting a minimally invasive surgical approach, coupled with vigilant monitoring and multidisciplinary follow-up, may enhance long-term functional outcomes[22]. The causes of postoperative dysfunction are still under debate, with hypothesized mechanisms including compression from large tumors and surgical trauma to pelvic organs or pelvic floor muscles, resulting in myogenic and/or neurogenic damage.

The long-term postoperative dysfunction rate in adults in this study was slightly higher than the 20.7% reported by Masahata et al[9] in infants and children. This discrepancy likely stems from the adult cohort’s characteristics: Lesions were generally larger and had more complex anatomical relationships with the sacral nerves. Moreover, some tumors were residual or recurrent from childhood, complicating surgical procedures and heightening the risk of nerve damage. In this study, the median maximum tumor diameter was 10.85 cm, and 35.9% of patients had Altman type III/IV tumors, both higher than typical pediatric figures. The challenges associated with nerve compression and intraoperative tumor mobilization may also contribute to the slightly elevated incidence of postoperative dysfunction observed here.

Although serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) has some value in monitoring embryonal tumors, current evidence does not support the use of single or routine AFP measurements as a reliable predictive marker for recurrence in SCT. Systematic reviews and multicenter follow-up studies have shown that AFP may have moderate sensitivity for detecting recurrence-particularly malignant recurrence-but this sensitivity is likely overestimated[7]. Moreover, no significant differences in AFP kinetics have been observed between patients with and without recurrence[24]. A normal or mildly elevated AFP level does not exclude recurrence, and absolute AFP values alone cannot distinguish mature (benign) recurrence from malignant recurrence. Therefore, clinical follow-up should focus on serial AFP monitoring in conjunction with imaging and pathological assessment. In the present study, the relationship between AFP and tumor recurrence was not analyzed, as all patients had benign tumors and most recurrent cases represented benign recurrence with serum AFP levels remaining within the normal range. Consequently, investigating serum AFP in this cohort would not have provided meaningful information.

The early detection of primary SCT or recurrence after resection depends on the combination of clinical, biochemical and imaging monitoring. Continuous monitoring of serum AFP is recommended because AFP value alone is an unreliable predictor of recurrence. Regular clinical examination (including digital rectal examination when feasible) and imaging (enhanced pelvic magnetic resonance imaging is recommended) should be performed. Intensive follow-up is recommended for the first 2-3 years, when most recurrences occur, and extended to 5-6 years in patients with immature histology, incomplete resection, or a malignant component.

This study has several limitations: Firstly, the relatively small sample size may introduce bias into certain analyses. Secondly, its single-center, retrospective design lacks the rigor of prospective planning and multicenter validation. Thirdly, the absence of a standardized, objective scoring system for evaluating postoperative dysfunction could lead to subjective interpretations. Lastly, there was no systematic follow-up or assessment of long-term gastrointestinal function. Future multicenter, prospective studies are warranted to confirm these findings and to explore more refined surgical strategies and postoperative rehabilitation approaches.

In conclusion, the retrospective study found no significant differences in postoperative complications or recurrence rates across various surgical approaches. However, independent risk factors for postoperative dysfunction were identified, including a maximum tumor diameter of 10 cm or more, Altman classification III/IV, and intraoperative blood loss of 400 mL or more, aligning with previous research findings[16,25]. Moreover, omitting sacrococcygeal resection substantially increased recurrence risk. This study offers clinical insights to refine surgical strategies and tailor treatment plans. Preoperatively, gastrointestinal function should be thoroughly evaluated, and pelvic nerves must be meticulously protected during surgery to mitigate intestinal dysfunction. Postoperative care should emphasize digestive system recovery through training, pharmacological therapy, dietary management, and long-term follow-up to enhance gastrointestinal motility and overall patient outcomes.

| 1. | Phi JH. Sacrococcygeal Teratoma: A Tumor at the Center of Embryogenesis. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2021;64:406-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sukhadiya MV, Das U. Laparoscopic Approach to Type IV Sacrococcygeal Teratoma in an Adult. Indian J Surg. 2015;77:62-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Golas MM, Gunawan B, Raab BW, Füzesi L, Lange B. Malignant transformation of an untreated congenital sacrococcygeal teratoma: a amplification at 8q and 12p detected by comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;197:95-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yao W, Li K, Zheng S, Dong K, Xiao X. Analysis of recurrence risks for sacrococcygeal teratoma in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:1839-1842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Derikx JP, De Backer A, van de Schoot L, Aronson DC, de Langen ZJ, van den Hoonaard TL, Bax NM, van der Staak F, van Heurn LW. Factors associated with recurrence and metastasis in sacrococcygeal teratoma. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1543-1548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Padilla BE, Vu L, Lee H, MacKenzie T, Bratton B, O'Day M, Derderian S. Sacrococcygeal teratoma: late recurrence warrants long-term surveillance. Pediatr Surg Int. 2017;33:1189-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | van Heurn LJ, Knipscheer MM, Derikx JPM, van Heurn LWE. Diagnostic accuracy of serum alpha-fetoprotein levels in diagnosing recurrent sacrococcygeal teratoma: A systematic review. J Pediatr Surg. 2020;55:1732-1739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Braungart S, James EC, Powis M, Gabra H; CCLG Surgeons Collaborators, Losty PD. Sacrococcygeal teratoma: Long-term outcomes. A UK CCLG Surgeons Group Nationwide Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2023;70:e29994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Masahata K, Ichikawa C, Makino K, Abe T, Kim K, Yamamichi T, Tayama A, Soh H, Usui N. Long-term functional outcome of sacrococcygeal teratoma after resection in neonates and infants: a single-center experience. Pediatr Surg Int. 2020;36:1327-1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhong Q, Zhang Q, Xiao Z, Zhang H. Laparoscopic transabdominal-sacrococcygeal approach for resection of Altman type III sacrococcygeal teratoma in adult women: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103:e37887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tankou J, Foley OW, Liu CY, Melamed A, Schantz-Dunn J. Dermoid cyst management and outcomes: a review of over 1000 cases at a single institution. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2024;231:442.e1-442.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Guo JX, Zhao JG, Bao YN. Adult sacrococcygeal teratoma: A review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e32410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lundbæk Siggaard LW, Ellebæk MB, Christensen LG, Brok J, Sperling L, Jørgensen PH, Johansen LS, Schomerus E, Nissen KB, Rathe M. Sacrococcygeal Teratomas in Children and Adolescents - A Danish 26-Year Retrospective Cohort Study. J Pediatr Surg. 2025;60:162412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jouzova A, Jouza M, Turek J, Gerychova R, Jezova M, Janku P, Hruban L. Sacrococcygeal teratoma - prognosis based on prenatal ultrasound diagnosis, single-center experience and literature review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2025;25:469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Baikady SS Sr, Singaram NK. Adult Onset Sacrococcygeal Teratoma. Cureus. 2023;15:e45291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fumino S, Hirohata Y, Takayama S, Tajiri T, Usui N, Taguchi T; Japan SCT Study Group Collaborators. Long-Term Outcomes of Infantile Sacrococcygeal Teratoma: Results from a Multi-Institutional Retrospective Observational Study in Japan. J Pediatr Surg. 2024;59:587-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Marković I, Stamenović S, Radovanović Z, Bosnjaković P, Ilić D, Stojanov D. Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging in prenatal diagnosis of sacrococcygeal teratoma--case report. Med Pregl. 2013;66:254-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Solanki S, Menon P, Samujh R, Gupta K, Rao KLN. Clinical Presentation and Surgical Management of Neonatal Tumors: Retrospective Analysis. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2020;25:85-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lukish JR, Powell DM. Laparoscopic ligation of the median sacral artery before resection of a sacrococcygeal teratoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1288-1290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Khedr EME, Tarek M, NasrEl-Din HM, Abdelsattar AH, Abdelazim O. Laparoscopic-assisted Combined Abdominal and Sacral Approach for Sacrococcygeal Teratoma Altman II/III Excision: Case Series. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2025;30:215-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hambraeus M, Hagander L, Stenström P, Arnbjörnsson E, Börjesson A. Long-Term Outcome of Sacrococcygeal Teratoma: A Controlled Cohort Study of Urinary Tract and Bowel Dysfunction and Predictors of Poor Outcome. J Pediatr. 2018;198:131-136.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ahmad H, Halleran DR, Vardanyan J, Mathieu W, Stanek J, Ranalli M, Levitt MA, Wood RJ, Aldrink JH. Functional fecal and urinary outcomes after sacrococcygeal mass resection in pediatric patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2021;56:1142-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cozzi F, Schiavetti A, Zani A, Spagnol L, Totonelli G, Cozzi DA. The functional sequelae of sacrococcygeal teratoma: a longitudinal and cross-sectional follow-up study. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:658-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | van Heurn LJ, Kremer MEB, de Blaauw I, van Baren R, van Gemert WG, van Goudoever JB, Sloots CEJ, Witvliet MJ, Ernest van Heurn LW, Derikx JPM. The Diagnostic Accuracy of Serum Alpha-Fetoprotein Levels in Follow-up for Recurrence of Sacrococcygeal Teratoma; a Nationwide Review of SCT Cases in the Netherlands. J Pediatr Surg. 2024;59:1740-1745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Salim A, Raitio A, Losty PD. Long-term functional outcomes of sacrococcygeal teratoma - A systematic review of published studies exploring 'real world' outcomes. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2023;49:16-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/