Published online Jan 24, 2026. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v17.i1.114238

Revised: October 12, 2025

Accepted: December 1, 2025

Published online: January 24, 2026

Processing time: 125 Days and 4.3 Hours

Early-onset colorectal cancer (EOCRC) is an aggressive malignancy with rising incidence and poor prognosis in young adults. Circulating immune cells may hold prognostic value, yet their role in EOCRC outcomes remains unclear.

To develop machine learning-based prognostic models using peripheral immune markers in a retrospective cohort of EOCRC patients.

A cohort of 123 EOCRC patients undergoing radical resection, from January 2017 to December 2020 was included. Data were extracted from medical records with a follow-up till July 2025. Blood samples were processed for flow cytometry to assess immune markers.

Univariable screening identified disease stage and CD16+CD56+ natural killer (NK) cell percentage as top predictors. A parsimonious Cox model integrating stage and high NK cells outperformed random survival forests (concordance index 0.693 vs 0.256). High-risk patients (stage III/IV, high NK cells) had inferior 5-year progression-free survival (61.2%; 95% confidence interval: 49.0-76.5) vs low-risk (86.4%; 95% confidence interval: 78.9-94.6; log-rank P = 0.001). Time-dependent areas under the curve ranged from 0.671 to 0.693, with robust cali

This two-factor model offers moderate accuracy for personalized EOCRC risk stratification, highlighting systemic NK cell dysfunction as a potential immunotherapy target. External validation is warranted.

Core Tip: Early-onset colorectal cancer (EOCRC) represents a growing public health challenge, characterized by aggressive biology and poor prognosis in young adults. While circulating immune cells play a pivotal role in cancer progression, their prognostic utility in EOCRC remains underexplored. In this study, we leveraged machine learning techniques to develop and validate a novel prognostic model integrating disease stage with peripheral CD16+CD56+ natural killer cell percentages. Our parsimonious Cox model demonstrated moderate discriminatory accuracy and clear risk stratification, with high-risk patients exhibiting significantly inferior progression-free survival. These findings highlight systemic natural killer cell dysfunction as a potential biomarker and immunotherapy target for EOCRC.

- Citation: Chen X, Wang Y, Shen HY, Wu R, Fu Z. Development and internal validation of an immune-based prognostic modeling of early-onset colorectal cancer via machine learning. World J Clin Oncol 2026; 17(1): 114238

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v17/i1/114238.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v17.i1.114238

Colorectal cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer associated death globally[1]. Early-onset colorectal cancer (EOCRC), defined as patients < 50 years old diagnosed with colon or rectal cancers, constitutes approximately 15% of newly diagnosed colorectal cancer patients[2]. Compared with late-onset colorectal cancer (≥ 50 years old), EOCRC is more aggressive in terms of epidemiological characteristics, histological biology, clinical features, prognosis and therapeutic strategies[3]. Over the past decades, the incidence of EOCRC has increased by approximately 45% and is the main cause of death in young men and the second most common cause of death in women[4,5]. Thus, there is an urgent need to focus more research on this emerging cancer subtype.

Circulating white blood cells, especially lymphocytes, monocytes and neutrophils are critical parts of the innate immune system[6]. Numerous studies have found alterations in the circulating white blood cell count as an important component of the progression and development of colorectal cancer[7,8]. For example, increased lymphocyte count [T cells, B cells or natural killer (NK) cells] has a protective effect on the risk and overall survival of colorectal cancer[9,10]. On the other hand, higher monocytes as well as neutrophil counts are associated with progression and worse survival of colorectal cancer[11,12]. However, the role of circulating immune cells in predicting outcomes for individuals with EOCRC remains uncertain. Therefore, this study aims to create a novel network model capable of identifying and delineating circulating immune cells and then explore its prognostic value in EOCRC patients.

For survival prediction, several statistical and machine learning techniques have emerged, ranging from the conventional Cox proportional hazards model to contemporary machine learning approaches such as random survival forests (RSFs), gradient boosting survival analysis, and least absolute shrinkage and selection operator-Cox regression. In contrast to Cox proportional hazard, machine learning algorithms provide enhanced capabilities in managing multicollinearity, high-dimensional data, and nonlinear relationships[13]. In this study, we collected real-world data to construct and internally validate a machine learning predictive model using circulating immune cell counts for the survival of EOCRC patients.

We reviewed a total of 783 colorectal cancer patients admitted to our institution from January 2017 to December 2020. Inclusion criteria were: (1) Patients with primary EOCRC diagnosed by pathological histology; (2) Those who underwent radical resection; and (3) Complete clinical records. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Patients aged < 18 years or > 50 years; (2) History of other concomitant cancers; and (3) Incomplete clinical information such as tumor-node-metastasis stage or preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level.

Data were extracted from electronic medical records including age, sex, tumor location, clinical stage, preoperative laboratory tests, surgical methods, chemotherapy regimen, postoperative pathology, survival status, date of progression and death. Patients were followed up until July 2025 through telephone or network contact. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital with Nanjing Medical University (Approval No. 2023-SR-206) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written consent was obtained from the patients or their offspring, when possible.

This was a retrospective cohort study involving all eligible EOCRC patients treated at our institution during the study period, yielding a convenience sample of 123 patients. No formal prior sample size calculation was performed. However, we evaluated the adequacy of the sample size using the events-per-variable (EPV) criteria. With 30 progression events and 2 variables in our final parsimonious model, the EPV was 15, which exceeded the commonly recommended min

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid anticoagulant tubes were used for blood collection, with approximately 5 mL collected in each tube. Red blood cell lysis buffer (1 mL) was added for 5 minutes and then fluorescent antibody according to the assay kit instructions: CD3-FITC/CD16+56-PE/CD45-PerCP-Cy5.5/CD4-PC7/CD19-APC/CD8-APC-Cy7 (Z6410010; Beijing Tongsheng Shidai Biotech Co., Ltd, China). After 30 minutes incubation, fluorescence values were detected.

Missing data were handled using multiple imputation by chained equations algorithm. Five imputed datasets were generated with 20 iterations, using predictive mean matching for continuous variables and polytomous logistic regression for categorical variables. All subsequent analyses were performed on each imputed dataset separately, and results were pooled using Rubin’s rules to identify uncertainty due to missing data.

To identify the most robust prognostic signature, we developed and formally compared two complementary modeling strategies: (1) A parsimonious model: To balance established clinical relevance with data-driven discovery in a sample of our size, this model was constructed by combining a prespecified core clinical predictor (disease stage) with the single most promising immune cell marker. The most promising marker was operationally defined as the one exhibiting the lowest P-value in univariable screening; and (2) A RSF model: This non-parametric ensemble method was trained on all candidate predictors with P < 0.10 to identify the most important variables based on permutation importance, thereby capturing potential non-linear effects and interactions.

These candidate models were then formally compared using the concordance index (C-index) and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). The model demonstrating the highest C-index was selected as the final model for all subsequent analyses, including validation and interpretation. This comparative approach ensured that our final model was chosen based on objective predictive performance rather than on a single variable selection rule.

The performance of the final model was comprehensively evaluated. Kaplan-Meier (KM) methods were used to estimate 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years progression-free survival (PFS), stratified by risk groups (high vs low) derived from the model’s linear predictor, with log-rank tests for between-group comparisons. Time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to assess discrimination at 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years; 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for areas under the curve (AUCs) were estimated using the Hanley-McNeil method. Model calibration was examined graphically at the median follow-up. Clinical utility was evaluated using decision curve analysis, and a nomogram was constructed to facilitate individualized risk prediction.

Robustness was assessed via 1000 bootstrap resamples [for hazard ratios (HRs)], prespecified subgroup analyses (age, sex, chemoradiotherapy), and sensitivity analyses (excluding metastasis M1 disease; including CEA). Analyses were conducted in R (version 4.4.3) using the packages survival, coxphf, randomForestSRC, glmnet, timeROC, gtsummary, survminer, rms, and ggDCA. Statistical significance was defined by a two-sided P-value < 0.05.

Baseline characteristics were summarized as mean ± SD for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables. Candidate predictors of PFS were screened using univariable Cox models; variables with a P-value < 0.10 were considered signals of association and retained for subsequent machine learning-based modeling.

We included 123 patients with a mean age of 42.8 years (SD 7.2); 52.8% (65/123) were male. Early-stage disease (I/II) accounted for 60.2% (74/123). Chemoradiotherapy was administered to 69.1% (85/123). The CD16+CD56+NK cell percentage was dichotomized into low (53.7%, 66/123) and high (46.3%, 57/123) groups. Distributions for other immune markers were similar [e.g., regulatory T cells (Treg)% low 52.8%, 65/123; high 47.2%, 58/123; Table 1).

| Characteristics | Overall (n = 123) | No progression (n = 93) | Progression (n = 30) |

| Age (years) | 42.8 ± 7.2 | 42.9 ± 7.0 | 42.7 ± 7.8 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 65.0 (52.8) | 50.0 (53.8) | 15.0 (50.0) |

| Female | 58.0 (47.2) | 43.0 (46.2) | 15.0 (50.0) |

| Stage | |||

| I-II | 74.0 (60.2) | 63.0 (67.7) | 11.0 (36.7) |

| III-IV | 49.0 (39.8) | 30.0 (32.3) | 19.0 (63.3) |

| Family | |||

| No | 82.0 (66.7) | 62.0 (66.7) | 20.0 (66.7) |

| Yes | 41.0 (33.3) | 31.0 (33.3) | 10.0 (33.3) |

| T stage | |||

| 1 | 7.0 (5.7) | 7.0 (7.5) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| 2 | 26.0 (21.1) | 24.0 (25.8) | 2.0 (6.7) |

| 3 | 74.0 (60.2) | 54.0 (58.1) | 20.0 (66.7) |

| 4 | 16.0 (13.0) | 8.0 (8.6) | 8.0 (26.7) |

| N stage | |||

| 0 | 69.0 (56.1) | 61.0 (65.6) | 8.0 (26.7) |

| 1 | 43.0 (35.0) | 25.0 (26.9) | 18.0 (60.0) |

| 2 | 11.0 (8.9) | 7.0 (7.5) | 4.0 (13.3) |

| M stage | |||

| 0 | 115.0 (93.5) | 91.0 (97.8) | 24.0 (80.0) |

| 1 | 8.0 (6.5) | 2.0 (2.2) | 6.0 (20.0) |

| CMOR | |||

| No | 116.0 (94.3) | 91.0 (97.8) | 25.0 (83.3) |

| Yes | 7.0 (5.7) | 2.0 (2.2) | 5.0 (16.7) |

| Chemoradiotherapy | |||

| No | 38.0 (30.9) | 36.0 (38.7) | 2.0 (6.7) |

| Yes | 85.0 (69.1) | 57.0 (61.3) | 28.0 (93.3) |

| Tumor necrosis | |||

| Negative | 122.0 (99.2) | 92.0 (98.9) | 30.0 (100.0) |

| Positive | 1.0 (0.8) | 1.0 (1.1) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| Vascular invasion | |||

| Negative | 94.0 (76.4) | 75.0 (80.6) | 19.0 (63.3) |

| Positive | 29.0 (23.6) | 18.0 (19.4) | 11.0 (36.7) |

| Nerve invasion | |||

| Negative | 94.0 (76.4) | 76.0 (81.7) | 18.0 (60.0) |

| Positive | 29.0 (23.6) | 17.0 (18.3) | 12.0 (40.0) |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 13.0 ± 49.2 | 4.8 ± 5.7 | 38.4 ± 96.0 |

| CD3+T (%) | |||

| ≤ 71.33 | 63.0 (51.2) | 47.0 (50.5) | 16.0 (53.3) |

| > 71.33 | 60.0 (48.8) | 46.0 (49.5) | 14.0 (46.7) |

| CD3+CD4+T (%) | |||

| ≤ 34.93 | 64.0 (52.0) | 48.0 (51.6) | 16.0 (53.3) |

| > 34.93 | 59.0 (48.0) | 45.0 (48.4) | 14.0 (46.7) |

| CD3+CD8+T (%) | |||

| ≤ 28.35 | 60.0 (48.8) | 45.0 (48.4) | 15.0 (50.0) |

| > 28.35 | 63.0 (51.2) | 48.0 (51.6) | 15.0 (50.0) |

| CD16+CD56+NK (%) | |||

| ≤ 17.13 | 66.0 (53.7) | 53.0 (57.0) | 13.0 (43.3) |

| > 17.13 | 57.0 (46.3) | 40.0 (43.0) | 17.0 (56.7) |

| CD19+B (%) | |||

| ≤ 1.32 | 59.0 (48.0) | 42.0 (45.2) | 17.0 (56.7) |

| > 1.32 | 64.0 (52.0) | 51.0 (54.8) | 13.0 (43.3) |

| CD4+T/CD8+T (%) | |||

| ≤ 71.33 | 66.0 (53.7) | 52.0 (55.9) | 14.0 (46.7) |

| > 71.33 | 57.0 (46.3) | 41.0 (44.1) | 16.0 (53.3) |

| Treg (%) | |||

| ≤ 8.47 | 65.0 (52.8) | 48.0 (51.6) | 17.0 (56.7) |

| > 8.47 | 58.0 (47.2) | 45.0 (48.4) | 13.0 (43.3) |

Following univariable Cox regression, several factors were found to be associated with PFS (P < 0.10), including stage (HR = 3.27, 95%CI: 4.68 to > 1000; P = 0.002), N stage (1 vs 0; HR = 4.51, 95%CI: 7.09 to > 1000; P < 0.001), N stage (2 vs 0) (HR = 3.87, 95%CI: 3.19 to > 1000; P = 0.028), M stage (HR = 5.57, 95%CI: 9.6 to > 1000; P < 0.001), combined multiple organ resection (CMOR) (HR = 4.24, 95%CI: 5.01 to > 1000; P = 0.003), chemoradiotherapy (HR = 7.29, 95%CI: 5.68 to > 1000; P = 0.007), vascular invasion (HR = 2.12, 95%CI: 2.74-86.15; P = 0.048), nerve invasion (HR = 2.30, 95%CI: 3.03-119.07; P = 0.025) and CEA (HR = 1.01, 95%CI: 2.73-2.75; P < 0.001; Table 2).

| Variable | Contrast | Hazard ratio | 95%CI | P value |

| Age | Per unit increase | 1.00 | 2.59-2.86 | 0.984 |

| CD16+CD56+NK | High vs low | 1.54 | 2.11-23.73 | 0.243 |

| CD19+B | High vs low | 0.65 | 1.37-3.82 | 0.243 |

| CD3+CD4+T | High vs low | 0.90 | 1.55-6.35 | 0.776 |

| CD3+CD8+T | High vs low | 0.96 | 1.6-7.08 | 0.903 |

| CD3+T | High vs low | 0.97 | 1.61-7.36 | 0.943 |

| CD4+T/CD8+T | High vs low | 1.37 | 1.95-16.62 | 0.388 |

| CEA | Per unit increase | 1.01 | 2.73-2.75 | < 0.001 |

| CMOR | Yes vs no | 4.24 | 5.01 to > 1000 | 0.003 |

| Chemoradiotherapy | Yes vs no | 7.29 | 5.68 to > 1000 | 0.007 |

| Family | Yes vs no | 0.92 | 1.52-7.55 | 0.836 |

| M | 1 vs 0 | 5.57 | 9.6 to > 1000 | < 0.001 |

| N | 1 vs 0 | 4.51 | 7.09 to > 1000 | < 0.001 |

| N | 2 vs 0 | 3.87 | 3.19 to > 1000 | 0.028 |

| Nerve invasion | Yes vs no | 2.30 | 3.03-119.07 | 0.025 |

| Sex | Female vs male | 1.14 | 1.75-10.34 | 0.718 |

| Stage | Stage in III-IV | 3.27 | 4.68 to > 1000 | 0.002 |

| T | 2 vs 1 | 8959622.29 | 1 to > 1000 | 0.997 |

| T | 3 vs 1 | 33760956.62 | 1 to > 1000 | 0.996 |

| T | 4 vs 1 | 63867920.40 | 1 to > 1000 | 0.996 |

| Treg | High vs low | 0.81 | 1.48-5.28 | 0.563 |

| Tumor necrosis | Yes vs no | 0.00 | 1 to > 1000 | 0.998 |

| Vascular invasion | Yes vs no | 2.12 | 2.74-86.15 | 0.048 |

On the basis of discrimination, the parsimonious model that included stage (III-IV vs I-II) and CD16+CD56+NK cell percentage (high vs low) was selected as the final model (C-index = 0.310; AIC = 261.5), outperforming the RSF model (C-index = 0.256; AIC = 240.3) by the C-index (Supplementary Table 1). In multivariable analysis, advanced stage remained associated with shorter PFS (HR = 2.98, 95%CI: 1.36-6.51; P = 0.012), while high CD16+CD56+NK cell percentage showed a trend toward shorter PFS; however, with no statistical significance (HR = 1.74, 95%CI: 0.67-4.55; P = 0.281; Supplementary Table 2). Confidence intervals were wide, consistent with the modest number of events.

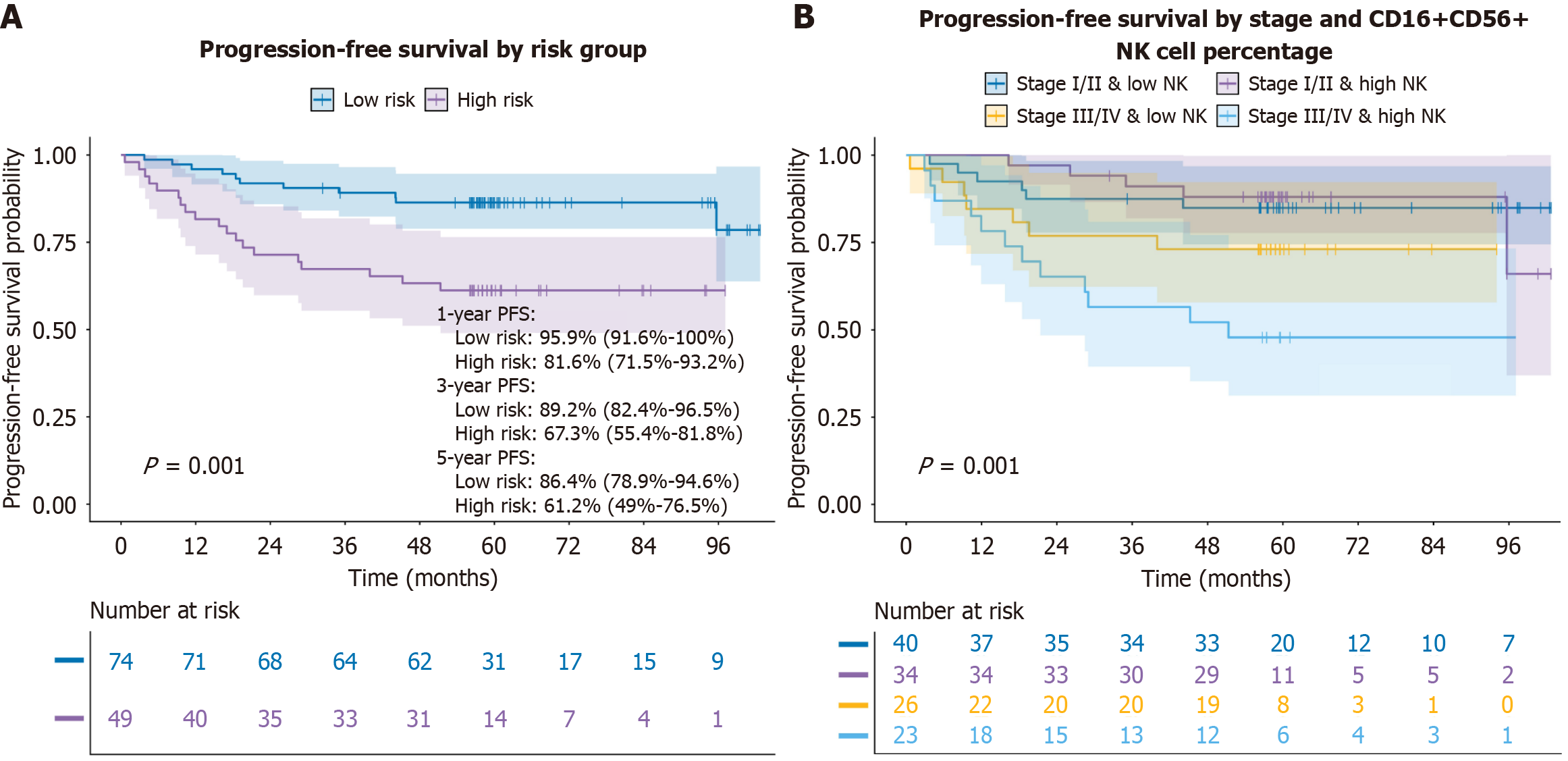

Median follow-up was 58.5 months, during which 30 progression events (24.4%) occurred. KM curves based on the final model’s risk score showed separation between groups (log-rank P = 0.001). Low-risk patients (n = 74) had 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years PFS of 95.9% (95%CI: 91.6-100.0), 89.2% (95%CI: 82.4-96.5), and 86.4% (95%CI: 78.9-94.6), respectively; corresponding estimates for high-risk patients (n = 49) were 81.6% (95%CI: 71.5-93.2), 67.3% (95%CI: 55.4-81.8), and 61.2% (95%CI: 49.0-76.5; Figure 1A; Supplementary Figure 1).

Stratified KM analyses suggested the poorest outcomes in patients with combined stage III/IV and high CD16+CD56+NK cell percentage (log-rank P = 0.001; Figure 1B). However, CD16+CD56+NK% alone was not associated with PFS (log-rank P = 0.24). Other immune markers, including CD3+T% (log-rank P = 0.94), CD3+CD4+T% (P = 0.78), CD3+CD8+T% (P = 0.9), CD4+/CD8+% (P = 0.39), Treg% (P = 0.56) and CD19+B% (P = 0.24), were also not significantly associated with PFS in univariable KM analyses (Supplementary Figure 2).

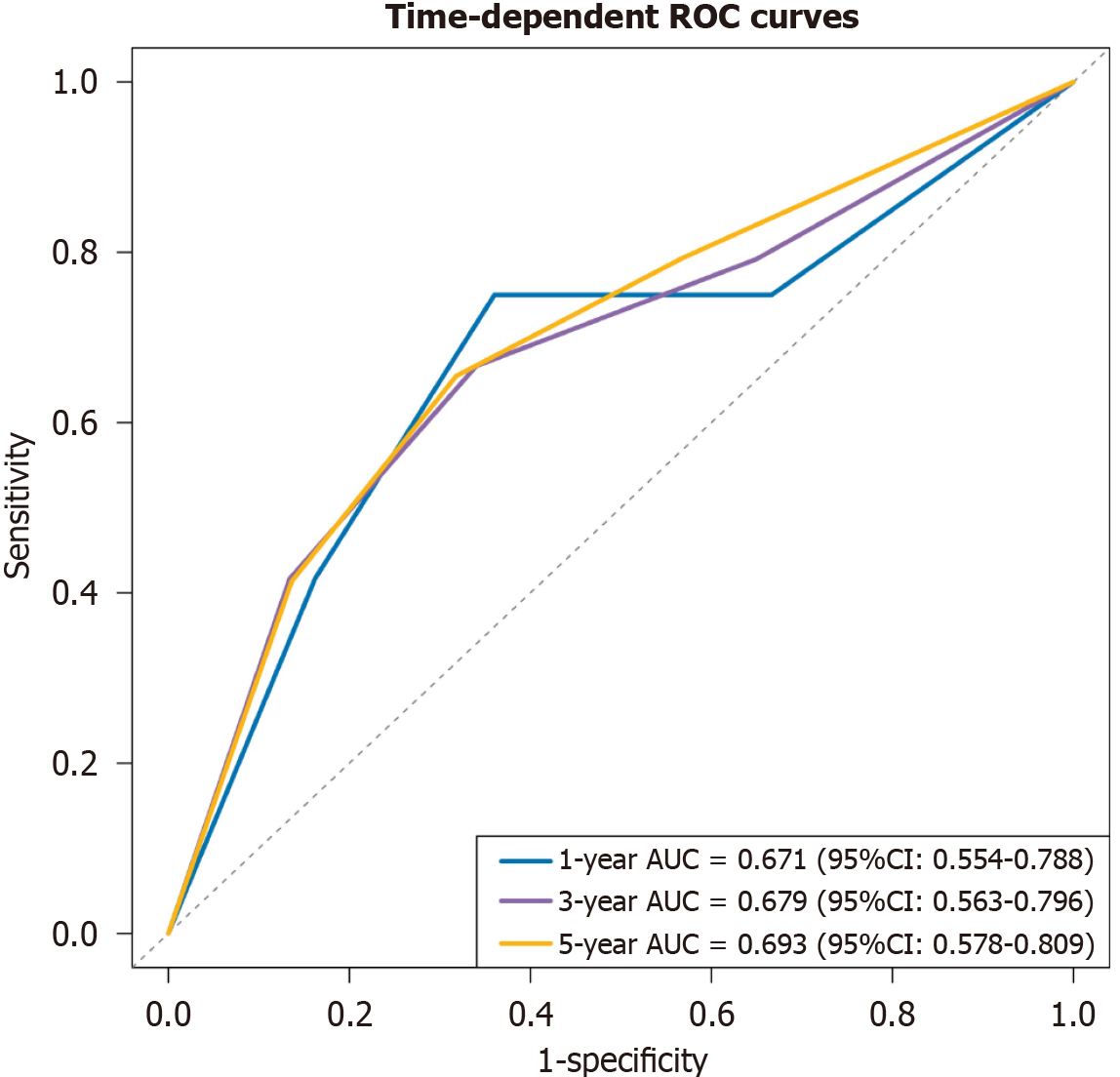

Time-dependent ROC curves demonstrated moderate discrimination: AUCs were 0.671 (95%CI: 0.554-0.788), 0.679 (95%CI: 0.563-0.796), and 0.693 (95%CI: 0.578-0.809) at 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years, respectively (Figure 2). Calibration at the median follow-up showed good agreement between predicted and observed PFS (Supplementary Figure 3). Bootstrap validation (1000 replications) supported the direction of effects, with bootstrap HRs of 3.61 (95%CI: 0.22-7.00) for stage and 1.72 (95%CI: 0.29-3.15) for CD16+CD56+NK cell percentage (Supplementary Table 3), although intervals were imprecise.

Effects of stage and CD16+CD56+NK cell percentage were directionally consistent across subgroups. For age < 45 years (n = 60), stage HR was 3.18 (95%CI: 2.92-12579.68; P = 0.037) and NK HR = 1.86 (95%CI: 1.93-187.57; P = 0.242); for age ≥ 45 years (n = 63), stage HR was 3.38 (95%CI: 3.32-13646.40; P = 0.021) and NK HR 1.30 (95%CI: 1.60-36.68; P = 0.609). Similar trends were observed across sex and chemoradiotherapy strata (Supplementary Table 4). Sensitivity analyses supported robustness: Excluding M1 patients (n = 115) yielded stage HR = 2.51 (95%CI: 3.05-287.72) and NK HR = 1.38 (95%CI: 1.86-21.95) with a C-index of 0.622; including CEA (n = 123) yielded stage HR = 2.98 (95%CI: 4.00-614.05) and NK HR = 1.76 (95%CI: 2.30-41.77) with a C-index of 0.705 (Supplementary Table 5). The wide CIs reflect limited events and potential sparsity in some strata.

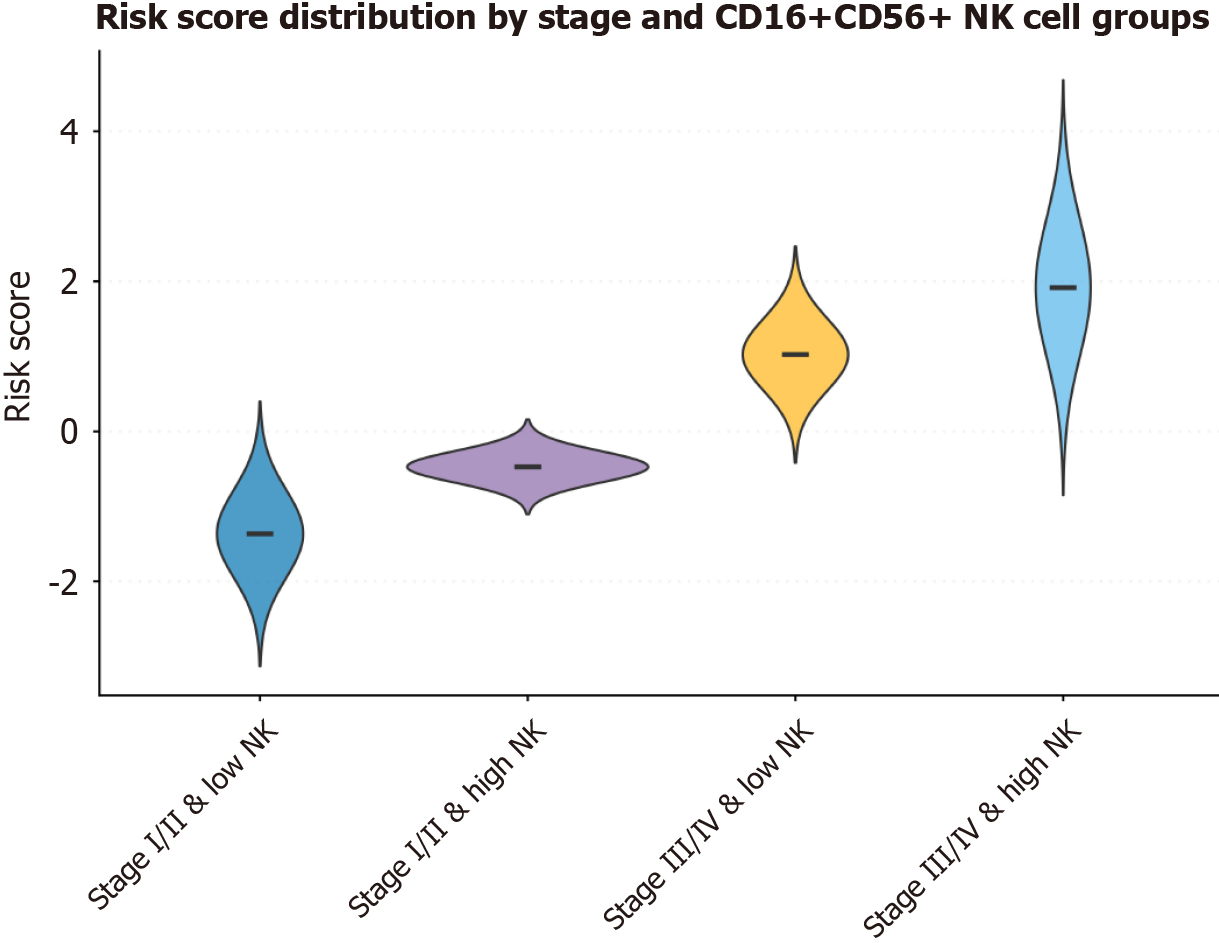

Risk scores were higher in the stage III/IV and high NK groups (Figure 3). Cumulative hazard curves showed greater event accumulation in the high-risk group (Supplementary Figure 4). The time-varying effect of CD16+CD56+NK cell percentage attenuated slightly over time (Supplementary Figure 5). The nomogram facilitated individualized estimation of 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year PFS probabilities. Patients with stage I/II and low CD16+CD56+NK cell percentage typically had a predicted 1-year PFS probability exceeding 90%, whereas those with stage III/IV and high CD16+CD56+NK cell percentage had approximately 70% predicted 3-year PFS probability and 60% predicted 5-year PFS probability (Supplementary Figure 6).

This study confirmed and quantified the prognostic dominance of anatomical stage in EOCRC patients. The HR for stage III/IV disease was consistently > 3 across the entire cohort and all pre-specified subgroups, corroborating decades of oncological evidence that locoregional and distant burden remains the cardinal driver of relapse. Notably, the effect was preserved even after excluding M1 patients, suggesting that locoregional stage III disease itself was sufficient to confer high progression risk. As traditional tumor-node-metastasis staging is not well defined and the prognosis of EOCRC does not always coincide with the pathology and surgical findings, a reliable noninvasive prediction tool such as an immune biomarker for the prognosis of EOCRC is needed.

Emerging studies have identified the essential status of immune cells and immune system in the survival of patients with EOCRC. A combination formula containing platelets, neutrophils, and lymphocytes was found to be associated with worse prognoses in EOCRC patients[14]. Although various available predictors were reported, the optimal prognostic indicators for EOCRC patients have not been identified.

Circulating immune cells were reported to be related to the development and prognosis of diverse non-cancerous diseases and cancerous diseases. The monocyte-lymphocyte ratio showed the best predictive value for cardiovascular mortality among adults without cardiovascular disease[15]. In newly diagnosed, non-metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma, circulating immune cells, especially CD3+T cells and the CD4/CD8 ratio, were significantly independent prognostic predictors[16]. Factor forkhead box protein 3+ Treg was observed to be positively associated with lung cancer risk, and the relative CD8+ counts was negatively associated with risks of lung and positive estrogen receptor breast cancer. A significant positive association was also found between factor forkhead box protein 3+ T cells and risks of colorectal and negative estrogen receptor breast cancer[17]. Peripheral NK T cells also showed prognostic significance in colorectal cancer[18]. Considering the character of NK T cells to link innate and adaptive immune reactions, NK T cells were found to be one of the promisingly immunotherapeutic methods in colorectal cancer[19]. However, the current available literature provides rare specific information on the relationship between circulating immune cells and the prognosis of EOCRC patients.

It is widely known that NK cells are classically viewed as potent cytotoxic effectors against tumor cells. However, numerous data have shown that not all circulating NK subsets are cytotoxic NK cells. Traditionally, NK cells are mainly classified as CD56brightCD16- (regulatory) and CD56dimCD16+ (cytotoxic) NK cells. Patients with solid tumors exhibit a systemic reprogramming of NK cells toward a hypofunctional, minimally activated phenotype, thereby fostering tumor initiation and progression[20]. In the tumor micro-environment, NK cells can be skewed toward a pro-angiogenic or immunosuppressive phenotype via interleukin-12, interleukin-18 or interferon-γ stimulation[21]. The percentage of peripheral CD16+CD56+NK cells was reported to be negatively associated with the prognosis of colorectal cancer patients[22]. Nevertheless, the value of CD16+CD56+NK cells in EOCRC is unknown. Therefore, our peripheral blood findings may therefore mirror systemic immunosuppression rather than effective anti-tumor immunity. This observation seems counter-intuitive as NK cells are classically regarded as powerful killers of tumor cells. Importantly, the prognostic effect of CD16+CD56+ percentage was not confounded by T cell, B cell, or Treg cell percentages, none of which were associated with PFS in univariable analyses. This specificity underscores the unique biology of NK cells in the context of this tumor type and warrants mechanistic validation.

In addition, our study also constructed a parsimonious, immune-informed prognostic model for PFS in a single-institution cohort of patients with EOCRC. By integrating only two variables - the stage and the proportion of circulating CD16+CD56+NK cells - we achieved moderate discriminatory accuracy (5-year AUC = 0.693) and good calibration, with clear separation of KM curves (log-rank P = 0.001). These findings extend current literature in principal ways.

Firstly, the nomogram we developed translates these two variables into individualized 1-year, 3-year and 5-year PFS probabilities, offering clinicians a practical tool for patient counselling and trial stratification. For example, a patient with stage I/II disease and low NK cell percentage has a predicted 5-year PFS > 85%, whereas a patient with stage III/IV and high NK cell percentage has a predicted 5-year PFS of approximately 60%. Such risk quantification could inform decisions on adjuvant therapy, frequency of surveillance imaging or eligibility for immune-oncology trials. Secondly, methodological strengths included the relatively long median follow-up (58.5 months), the low attrition rate (only 24.4% progression events), and rigorous internal validation via bootstrap resampling. The time-dependent ROC curves demonstrated stable AUCs across 1-year, 3-year and 5-year landmarks, indicating that the model retained predictive value even as follow-up increased. Calibration plots further corroborated reliability, with predicted probabilities closely matching observed outcomes at the median follow-up.

Several limitations merit discussion. The foremost concern is the modest discriminatory performance (AUC = 0.69), which, although comparable to other immune-based prognostic models in solid tumors, leaves room for improvement. Also, external validation in larger, multi-center cohorts is essential before clinical adoption. We are actively pursuing multicenter collaborations to obtain external validation cohorts and encourage other investigators to test our model in their own EOCRC populations. Further research is expected to focus on mechanistic insights into why high CD16+CD56+NK percentage portends worse outcomes of EOCRC.

We present a clinically feasible two-factor model that integrated anatomical stage and systemic NK cell immunophenotyping to predict PFS of EOCRC patients with moderate accuracy. The findings facilitate personalized surveillance strategies and rational patient selection for adjuvant or neoadjuvant immunotherapies in EOCRC. External validation in independent cohorts is essential before clinical implementation to assess model transportability and generalizability.

We thank Peng Lu for his help in the statistical analysis.

| 1. | Siegel RL, Kratzer TB, Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin. 2025;75:10-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 1596] [Article Influence: 1596.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Sinicrope FA. Increasing Incidence of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1547-1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 87.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Patel SG, Karlitz JJ, Yen T, Lieu CH, Boland CR. The rising tide of early-onset colorectal cancer: a comprehensive review of epidemiology, clinical features, biology, risk factors, prevention, and early detection. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:262-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 522] [Article Influence: 130.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 4. | He JH, Cao C, Ding Y, Yi Y, Lv YQ, Wang C, Chang Y. A nomogram model for predicting distant metastasis of newly diagnosed colorectal cancer based on clinical features. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1186298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:233-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1859] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 6. | Quail DF, Amulic B, Aziz M, Barnes BJ, Eruslanov E, Fridlender ZG, Goodridge HS, Granot Z, Hidalgo A, Huttenlocher A, Kaplan MJ, Malanchi I, Merghoub T, Meylan E, Mittal V, Pittet MJ, Rubio-Ponce A, Udalova IA, van den Berg TK, Wagner DD, Wang P, Zychlinsky A, de Visser KE, Egeblad M, Kubes P. Neutrophil phenotypes and functions in cancer: A consensus statement. J Exp Med. 2022;219:e20220011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 59.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wu J, Ge XX, Zhu W, Zhi Q, Xu MD, Duan W, Chen K, Gong FR, Tao M, Shou LM, Wu MY, Wang WJ. Values of applying white blood cell counts in the prognostic evaluation of resectable colorectal cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2019;19:2330-2340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rosman Y, Hornik-Lurie T, Meir-Shafrir K, Lachover-Roth I, Cohen-Engler A, Munitz A, Confino-Cohen R. Changes in peripheral blood eosinophils may predict colorectal cancer - A retrospective study. World Allergy Organ J. 2022;15:100696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Constantinescu AE, Bull CJ, Jones N, Mitchell R, Burrows K, Dimou N, Bézieau S, Brenner H, Buchanan DD, D'Amato M, Jenkins MA, Moreno V, Pai RK, Um CY, White E, Murphy N, Gunter M, Timpson NJ, Huyghe JR, Vincent EE. Circulating white blood cell traits and colorectal cancer risk: A Mendelian randomisation study. Int J Cancer. 2024;154:94-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Martinez-Usatorre A, Ciarloni L, Angelino P, Wosika V, Conforte AJ, Fonseca Costa SS, Durandau E, Monnier-Benoit S, Satizabal HF, Despraz J, Perez-Uribe A, Delorenzi M, Morgenthaler S, Hashemi B, Hadadi N, Hosseinian-Ehrensberger S, Romero PJ. Human blood cell transcriptomics unveils dynamic systemic immune modulation along colorectal cancer progression. J Immunother Cancer. 2024;12:e009888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yamamoto T, Kawada K, Obama K. Inflammation-Related Biomarkers for the Prediction of Prognosis in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:8002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 64.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Olingy CE, Dinh HQ, Hedrick CC. Monocyte heterogeneity and functions in cancer. J Leukoc Biol. 2019;106:309-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 338] [Cited by in RCA: 426] [Article Influence: 60.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rajkomar A, Dean J, Kohane I. Machine Learning in Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1347-1358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1274] [Cited by in RCA: 1900] [Article Influence: 271.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 14. | Xiang S, Yang YX, Pan WJ, Li Y, Zhang JH, Gao Y, Liu S. Prognostic value of systemic immune inflammation index and geriatric nutrition risk index in early-onset colorectal cancer. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1134300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gupta K, Kalra R, Pate M, Nagalli S, Ather S, Rajapreyar I, Arora P, Gupta A, Zhou W, San Jose Estepar R, Di Carli M, Prabhu SD, Bajaj NS. Relative Predictive Value of Circulating Immune Markers in US Adults Without Cardiovascular Disease: Implications for Risk Reclassification. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96:1812-1821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Xie H, Zhang L, Chen L, Zhou W, Zhang L, Su Y, Li B, Ding P, Xiao Y, Lu T, Gong X, Li J. Prognostic Significance of Circulating Immune Subset Counts in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Immunotargets Ther. 2025;14:577-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Le Cornet C, Schildknecht K, Rossello Chornet A, Fortner RT, González Maldonado S, Katzke VA, Kühn T, Johnson T, Olek S, Kaaks R. Circulating Immune Cell Composition and Cancer Risk: A Prospective Study Using Epigenetic Cell Count Measures. Cancer Res. 2020;80:1885-1892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tang YP, Xie MZ, Li KZ, Li JL, Cai ZM, Hu BL. Prognostic value of peripheral blood natural killer cells in colorectal cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Singer M, Valerin J, Zhang Z, Zhang Z, Dayyani F, Yaghmai V, Choi A, Imagawa D, Abi-Jaoudeh N. Promising Cellular Immunotherapy for Colorectal Cancer Using Classical Dendritic Cells and Natural Killer T Cells. Cells. 2025;14:166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Saito LM, Ortiz RC, Amôr NG, Lopes NM, Buzo RF, Garlet GP, Rodini CO. NK cells and the profile of inflammatory cytokines in the peripheral blood of patients with advanced carcinomas. Cytokine. 2024;174:156455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang H, Grzywacz B, Sukovich D, McCullar V, Cao Q, Lee AB, Blazar BR, Cornfield DN, Miller JS, Verneris MR. The unexpected effect of cyclosporin A on CD56+CD16- and CD56+CD16+ natural killer cell subpopulations. Blood. 2007;110:1530-1539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cui F, Qu D, Sun R, Nan K. Circulating CD16+CD56+ nature killer cells indicate the prognosis of colorectal cancer after initial chemotherapy. Med Oncol. 2019;36:84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/