Published online Jan 24, 2026. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v17.i1.113600

Revised: September 16, 2025

Accepted: November 26, 2025

Published online: January 24, 2026

Processing time: 144 Days and 3 Hours

Mitochondrial translation relies on the coordinated activity of mitoribosomes, mitochondrial ribosome proteins, mitochondria-specific transfer RNAs, and dedicated translation factors, including mitochondrial initiation factor 2/3, mitochondrial elongation factor Tu, mitochondrial elongation factor Ts, mito

Core Tip: Mitochondrial translation machinery synthesizes 13 essential oxidative phosphorylation proteins through specialized ribosomes, translation factors and mitochondrial ribosomal proteins. This review demonstrates how the dysregulation of these components drives key cancer hallmarks, including sustained proliferation through enhanced adenosine triphosphate production, resistance to cell death via disrupted reactive oxygen species/AMP-activated protein kinase signaling, and invasion and metastasis through epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cytoskeletal remodeling. Preclinical evidence supports therapeutic targeting using agents like tigecycline and nanobodies, showing significant anti-tumor effects across multiple cancer types. Translation factors emerge as both prognostic biomarkers and actionable therapeutic targets, positioning mitochondrial translation as a promising vulnerability for metabolism-based cancer treatments with clinical translation potential.

- Citation: Agarwal N, Sharma U, Shree A, Kumar RR, Gorain JK, Vishwas V, Jahan F, Singh A, Palanichamy JK, Pushpam D, Bakhshi R, Chopra A, Sahoo RK, Batra A, Sharawat SK, Bakhshi S. Pleiotropic regulation of mitochondrial translational factors in governing proliferation, apoptosis and metastasis during cancer progression. World J Clin Oncol 2026; 17(1): 113600

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v17/i1/113600.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v17.i1.113600

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles essential for various cellular processes, including adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis via oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), metabolic regulation, and cellular signaling pathways[1]. The precise regulation of mitochondrial activities is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis and adaptive responses to environmental stimuli[1]. Disruptions in mitochondrial dynamics and bioenergetics have been linked to a range of pathologies, notably in oncogenesis, where altered mitochondrial metabolism can influence tumor progression and response to therapies[2,3].

Focusing on mitochondrial translation has become increasingly important due to the metabolic dependency of cancer cells and the distinct structural differences in their machinery compared to cytoplasmic translation[4,5]. Mitochondria harbor a unique protein synthesis system essential for energy production and cellular homeostasis, as mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) encodes essential components of the OXPHOS system[5]. Mitochondrial translation is carried out by ribosomes known as mitoribosomes, translation factors like mitochondrial initiation factor (MTIF) 2, mitochondrial elongation factor Tu (TUFM), mitochondrial elongation factor G1 (GFM1), mitochondrial ribosome recycling factor (MRRF), transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and mitochondrial ribosomal proteins (MRPs)[4]. The most fundamental challenge in mitochondrial targeting lies in the organelle’s complex double-membrane structure. Therapeutic agents must traverse multiple cellular barriers like plasma membrane permeability, cytosolic barriers, endolysosomal entrapment before reaching to mitochondria. Mitochondrial diseases are phenotypically and genetically heterogeneous, which creates several challenges in treatment[6,7]. Nonetheless, targeting mitochondrial translation offers unique therapeutic advantages through selective vulnerability of mitoribosomes to specific antibiotics while sparing cytoplasmic ribosomes, structural uniqueness with distinct ribosomal RNA (rRNA)/protein composition providing specific drug binding sites, and evolutionary divergence creating multiple distinct molecular targets. The specialized function of synthesizing only 13 essential OXPHOS proteins enables metabolic intervention strategies, while context-specific inhibition mechanisms allow sequence-selective targeting approaches with reduced off-target effects and improved therapeutic specificity.

Emerging studies have explored the targeting of mitochondrial translation in various cancers. For instance, Myc-driven lymphomas exhibit heightened sensitivity to mitochondrial translation inhibitors like tigecycline, with preclinical models showing prolonged survival[8]. Elevated expression of TUFM is associated with proliferation and migration capacity of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) cells[9]. Knockdown of mitochondrial elongation factor 4 (mtEF4) in lung cancer cells reduces basal oxygen consumption rate and increases basal extracellular acidification rates, linking mitochondrial translation to bioenergetic shifts[10]. In estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor (+) breast tumors, there is a significant correlation between altered expression of MRPs and OXPHOS subunits (Table 1)[11]. Certain MRPs have been recognized as potential oncogenes, like MRP large subunit (MRPL) 11, which may act as biomarkers for the progression and metastatic potential of human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC; Table 1)[12,13]. Likewise, elevated levels of MRP small subunit (MRPS) 23 and MRPL27 promote the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and cholangiocarcinoma, respectively and are associated with poor survival rates (Table 1)[14,15].

| No. | Cancer | Samples | Translation factor involved | Expression | Mechanism of action | Techniques and assays performed | Application in clinical settings | Ref. | |||

| Cell lines | Clinical samples | Animal models | |||||||||

| Control | Patients | ||||||||||

| 1 | HNSCC | HaCaT, HN8, HN12, HN13, HN22 | NA | n = 6 | NA | MRPL11 | Downregulated | Impaired mitochondrial translation due to reduced expression of MRPL11 leads to defective synthesis of mitochondrial-encoded proteins (e.g., COII), which in turn impairs OXPHOS. This defect potentially forces a metabolic shift to aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect), aiding tumor survival and progression, particularly in metastatic sites | Western blotting, qRT-PCR, wound healing assays | MRPL11 downregulation and mitochondrial translation defects may serve as biomarkers for HNSCC progression and metastatic potential | [13] |

| 2 | LC and BC | A549, CCL64, NCI-H446, MCF7, MDA-MB-453, MDAMB-231 and 293T | NA | NA | Nude mouse (n = 5) | TUFM | Upregulated | Loss of TUFM induces EMT and metastasis of lung cancer cells via a mechanism involving activation of the AMPK/GSK3β/β-catenin pathway | Cell migration assays, colony formation, cell cycle analysis, BrdU cell proliferation assay; qRT-PCR; western blotting and immunofluorescent staining, lentiviral transduction, analysis of glycolytic activity, measurement of cellular ROS; nuclear extraction; ATP and NAD1/NADH quantification; measurement of enzyme activity in complex I and complex IV, tissue microarray; IHC | NA | [31] |

| 3 | HNSCC | PCI-13, UDSCC2, SCC90, UMSCC22b | NA | n = 23 | NA | TUFM | Upregulated | TUFM, together with NLRX1, forms a mitochondrial complex that: (1) Promotes beclin-1 polyubiquitination; (2) Disrupts beclin-1 and rubicon interaction (which otherwise suppresses autophagy); and (3) Promotes ER stress signaling (eIF2α phosphorylation, UPR activation). This autophagy induction counteracts the anti-proliferative effects of EGFR inhibitors | RNAi-based protein expression knockdown and plasmid transfection, Western blots and co-immunoprecipitation; laser confocal imaging and colocalization analysis, TMA analysis | Increased p62 expression post-treatment is associated with poor response to cetuximab, suggesting: (1) p62 could serve as a predictive biomarker for cetuximab response; and (2) Targeting autophagy (e.g., TUFM, Beclin-1 interaction) may improve therapeutic response | [34] |

| 4 | Myc-driven lymphoma | Eμ-myc lymphoma cells (murine), Ba/F3 cells, R26-MERT2 MMECs, Raji, Ramos, Namalwa, Daudi (human Burkitt’s lymphoma) | NA | NA | C57BL/6J mice | MRPS5, MRPS27, PTCD3 | Upregulated | Activation of c-Myc sensitizes tumor cells to mitochondrial translation inhibition | shRNA library screen, immunoblot analysis; RNA extraction, qRT-PCR, cell growth and apoptosis assay; OCR, ATP and mitochondrial membrane potential measurement; histology and IHC staining | The identification of Myc as a determinant of tigecycline sensitivity provides a new potential indicator for the re-purposing of this antibiotic in the clinical setting | [8] |

| 5 | DLBCLs | DHL4, DHL6, Ly1, Toledo, Pfeiffer, K422, Ly4, DHL2, U2932, HBL-1 | NA | Not given | NA | MRPL12, GFM1 MRPS7, MRPS25, MRPS22, MRPS5, MRPS9, YARS2 DARS2, MRPL46, TUFM, MRPS16, PUS1 | Upregulated | NA | Mitochondria isolation; iTRAQ labeling; deep sequencing; mass spectrometry, RNAi; Tigecycline treatment; viability and proliferation assays; biochemical measurement of respiratory chain enzyme activity; analysis of mitochondrial respiratory chain super complexes; measurement of mitochondrial SRC; determination of mitochondrial superoxide content, analysis of primary DLBCL samples | Tigecycline selectively inhibits mtDNA-encoded protein translation | [50] |

| 6 | Colorectal carcinoma | NA | n = 261 | n = 261 | NA | TUFM | Upregulated | This association indicated that upregulated TUFM expression during the colorectal normal–adenoma–carcinoma sequence may contribute to the transformation from normal mucosa to carcinoma through adenoma | IHC | NA | [35] |

| 7 | RCC | 786-0 and A-498 | NA | NA | BALB/C mice | TUFM | Upregulated | Knockdown of TUFM along with tigecycline treatment in RCC cells leads to reduced cell growth and survival as a consequence of the suppression of essential growth/ survival signaling pathway PI3K/AKT/mTOR | Measurement of cell proliferation; apoptosis and colony formation; western blotting; qRT-PCR; mitochondrial complex activities; measurement of mitochondrial respiration; RNAi of human EF-Tu expression; RCC cancer xenograft mouse model | NA | [36] |

| 8 | HCC | MHCC97-H, SMMC-7721 | n = 50, TCGA | n = 50, TCGA | Nude mice (BALB/C) | MRPS23 | Upregulated | MRPS23 overexpression contributes to: (1) Enhanced proliferation of HCC cells in vitro and in vivo; (2) Associated with larger tumor size, higher TNM stage, and shorter survival; (3) May promote proliferation through enhanced oxidative phosphorylation and changes in tumor metabolism; and (4) No significant role found in migration/invasion | HCC tissue microarray and IHC analysis; lentiviral infection; RNA extraction; qRT-PCR; western blotting; immunofluorescence; cell proliferation and colony formation assay; cell migration and invasion assays | High MRPS23 expression contributes to HCC proliferation and indicates poor survival outcomes | [14] |

| 9 | Breast cancer | MCF10A, MCF7, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-435, MDA-MB-468 | NA | n = 366 | NA | NA | Upregulated | RK-33 inhibits DDX3 blocks mitochondrial translation. Consequences: Mitochondrial-encoded proteins; OXPHOS capacity and ATP production; reactive oxygen species (ROS); apoptosis and autophagy; radiation-induced DNA repair; leads to a bioenergetic catastrophe in cancer cells | Cell viability assays; immunoblotting; proteomics; immunofluorescence; mitochondrial translation assay; measurements of oxygen consumption; ATP quantification; mitotracker flow cytometry; measurement of reactive oxygen species; electron microscopy; colony forming assay | RK-33 serves as a radiosensitizer in breast cancer and is a potent inhibitor of mitochondrial translation, which consequently diminishes the mitochondrial OXPHOS capacity and elevates ROS production in cancer cells | [54] |

| 10 | Colorectal cancer | RKO (colon cancer), Hela (cervical cancer), SK-Hep-1 (liver cancer), ZR-75-30 (BC), CRL-5803 (LC), MGC-803 (gastric cancer) | NA | n = 60 | Nude mice | MRPL33 | Upregulated | Role played by MRPL33-L (an isoform of MRPL33) proteins in colon cancer cell growth, cancer development and repress cancer cell apoptosis | Cell growth and colony-survival assay, RNA isolation; qRT-PCR; western blotting and immunoprecipitation, Generation of recombinant lentivirus and MRPL33 minigenes; mitochondria staining; ROS assay; ATP detection and analysis of apoptosis; RNA-seq | NA | [46] |

| 11 | LC; cervical cancer; esophageal cancer; bladder cancer | HeLa, H1299, A549, MDA-MB-231, HepG2, SK-MES-1, H460, K562, PC3, HFF (control), 16HBE, PASMC | Not given | Not given | Nude mice | mtEF4 | Upregulated | Low mtEF4 increases mt-translation but decreases translational fidelity, leading to low-quality respiratory chain complexes that may degrade or yield less ATP and more ROS, increasing apoptosis risk. High mtEF4, however, boosts respiratory chain complexes production, raising ATP and ROS levels, vital for cellular energy and signaling | RNA extraction; qRT-PCR; western blot; TEM; OCR and ECAR, TCA metabolites assay; BNG and IGA; estimation of mitochondrial ROS production; detection of MMP; ATP assay; tumor growth assay; cell proliferation and apoptosis | NA | [10] |

| 12 | GBM | U251MG, U87MG, HaCaT cells (human keratinocyte cell line), GSCs, NSCs | Not given | Not given | NA | TUFM | Upregulated | Nanobody Nb206 binds TUFM interferes with GSCs and GBM cells’ proliferation and viability | Immunoaffinity enrichment (bio-panning); ELISA; mass spectrometry and antigen identification; qRT-PCR; western blotting; cytotoxicity measurements; apoptosis and necrosis, IHC | Nanobody-based targeting may bypass limitations of traditional antibodies, particularly in crossing the blood-brain barrier | [37] |

| 13 | Ovarian cancer | SW626, SK-OV-3 (ovarian cancer); HIOEC (normal ovarian epithelial); BJ-5ta (normal fibroblast) | NA | NA | SCID mice | Mitochondrial ribosomes | NA | Tigecycline specifically inhibits translation by mitochondrial ribosome but not nuclear or cytosolic ribosome, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and damage, AMPK activation and inhibition of mTOR signaling in ovarian cancer cells | Generation of mitochondrial DNA deficient r0 cell line; qRT-PCR, proliferation, cell cycle and apoptosis analysis, Mito stress test assay, measurement of oxidative stress and damage; xenograft ovarian cancer model | Tigecycline and cisplatin demonstrate synergistic effects in both in vitro and in vivo studies, suggesting potential for overcoming cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer treatment | [58] |

| 14 | Osteosarcoma | MG63, U-2 OS, Saos-2, HOS | NA | NA | SCID mouse | TUFM | Upregulated | Knockdown of TUFM and tigecycline’s anti-cancer activities include inhibition of mitochondrial translation, suppression of Wnt/b-catenin, p21CIP1/WAF1 and miRNA-199b-5p-HES1 AKT pathway; Tigecycline selectively inhibits mitochondrial translation, impairs mitochondrial respiration, induces apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells | Drug and generation of mitochondrial DNA deficient r0 cell line; measurement of proliferation and apoptosis; siRNA knockdown and qRT-PCR; OCR; Measurement of mitochondrial biogenesis; osteosarcoma xenograft in SCID mouse | NA | [53] |

| 15 | AML | MOLM13-R1, MOLM13-R2, SU048-R | NA | Not given | NSG mice | MRPS29 | NA | NA | Flow cytometric analysis; NSG xenotransplantation; drug treatment; leukemic burden analysis | Inhibition of mitochondrial translation is an effective approach to overcoming venetoclax resistance and provide a rationale for combining tedizolid, azacitidine, and venetoclax as a triple therapy for AML | [52] |

| 16 | BC | MCF7, ZR-75-1, BT-474, BT-549, MDA-MB-231, AU565, MDA-MB-361, control cell lines- MCF-10F | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | GA-TPP+C10 causes: (1) Initial mitochondrial uptake and OXPHOS uncoupling; (2) Complex I inhibition; (3) αKGDHC inhibition; and (4) Induction of a glycolytic shift and AMPK-PGC1α mediated adaptive response. Doxycycline blocks: (1) Adaptive mitochondrial biogenesis by inhibiting mitochondrial translation; and (2) Leads to mitonuclear protein imbalance and synergistic cancer cell death when combined with GA-TPP+C10 | MTT assay and crystal violet staining (cell viability); seahorse extracellular flux analysis (OCR and ECAR); qRT-PCR; western blot; flow cytometry (Annexin V/PI apoptosis assay, cell cycle analysis); αKGDHC activity assay; colony formation assay | Combination of a mitochondria-targeted metabolic inhibitor (GA-TPP+C10) and a mitochondrial translation inhibitor (doxycycline) demonstrates selective synergistic killing of breast cancer cells while sparing normal cells | [55] |

| 17 | GBM | NHA cells, HA cells, and U-87MG, U-138MG, U-251MG | n = 4 | n = 61 | Nude mice | MRPS16 | Upregulated | MRPS16 over-expression remarkably promotes tumor cell growth, migration and invasion via the PI3K/AKT/Snail axis, which may be a promising prognostic marker for glioma | Western blotting; qRT-PCR; EdU; CCK-8; colony formation; transwell migration and invasion assays; coimmunoprecipitation | MRPS16 over-expression is a promising prognostic marker for glioma | [32] |

| 18 | GBM | U251MG, U87MG (mature GBM); NCH644, NCH421k (GSCs); HA cells | Not given | Not given | NA | TUFM | Upregulated | Nanobodies bind target proteins inhibit cell viability, induce apoptosis/necrosis, and reduce cell migration | qRT-PCR; ELISA; IHC; apoptosis/necrosis assays; cell migration assays | NA | [38] |

| 19 | GIST | GIST-T1 (KIT exon 11 mutation) and IM-resistant GIST-IR cells (induced via imatinib) | NA | NA | NA | TUFM | Upregulated | TUFM-knockdown decreased the proliferation and migration capacity of GIST-T1 and GIST-IR cells | TUFM silencing plasmids and electric transfection; qRT-PCR; western blotting; cell morphology and fluorescence assessment; cell proliferation and viability assays; wound healing and transwell assays; cell cycle determination | TUFM may serve as an effective target to inhibit early hematogenous metastasis, as well as postoperative recurrence and metastasis in patients with GIST, even in IM-resistant patients | [9] |

| 20 | HCC | Hepa 1-6, HepG2 | Not given, GEO and TCGA dataset | Not given, GEO and TCGA dataset | C57 mice | MTIF2 | Upregulated | MTIF2 suppression enhances apoptosis in HCC by modulating interactions with the apoptosis-inducing factor AIFM1, which can promote caspase3 expression. Also, down-regulation of MTIF2 impaired the proliferative and migratory abilities of HCC cells | Data acquisition and preprocessing; construction of co-expression network; establishment of module-trait relationship; pathway enrichment analysis; identification of hub genes, Cox risk regression and GSEA enrichment analysis; ATP assay; flow cytometry analysis; ELISA; cell viability assay; luciferase reporter assay; western blot analysis and IP | Overexpression MTIF2 impairs drug-induced immunogenic cell death in HCC, and a combination of treatment with MTIF2-knockdown may enhance the effect of chemotherapy | [42] |

| 21 | Cholangiocarcinoma | NA | NA | n = 36 | NA | MRPL27 | Upregulated | MRPL27 mainly involved in the processes of mitochondrial translation elongation, respiratory electron transport, ATP synthesis, and inner mitochondrial membrane organization | Survival analysis; PPI and enrichment, functional enrichment of interacted genes of MRPL27; identification of MRPL27 mutations | Upregulation of MRPL27 in tumor tissues predicted worse OS and DFS in cholangiocarcinoma patients | [15] |

| 22 | GBM | COMI, VIPI cells | NA | NA | NA | TUFM, MRPS18A | NA | Genetic inhibition of mitochondrial translation nearly completely abolished gliomasphere formation | Cas9 cell line generation; lentiviral vectors production; generation of knockout cell lines; viability assays; gliomasphere formation assay; cell cycle assay; apoptosis assay; autophagy assays; cryo-EM data and its processing; immunoblotting; immunofluorescence; RNA extraction; qRT-PCR; BNG and IGA assay, respiration assay; mitochondrial membrane potential assessment, lactate assay; competition assay | NA | [39] |

| 23 | BC | MCF-7, SKBR3, MDAMB231, MDAMB468, BU 25 TK, SiHa, HeLa, HTB34, SNU 638, AGS, NUGC, NCIH460, A549 | NA | NA | NA | MRPS9, MRPS10, MRPS11, MRPS18B, MRPS31, MRPS33, MRPS38, MRPS39 | MRPS10 and MRPS31- upregulated | MRPS proteins interact with non-mitoribosomal proteins (e.g., p53, ROS1, ACADSB). Involvement in cancer pathways: PIP3/AKT, MAPK, Wnt, Hedgehog, Estrogen signaling, G2/M transition, apoptosis, NF-κB, circadian rhythm | qRT-PCR, western blotting; MALDI; FPLC, GST pull-down assay; mass spectrometry; network and gene ontology analysis | MRPS10 and MRPS31 could serve as biomarkers or therapeutic targets in breast cancer | [44] |

| 24 | RCC | HK-2, 786-O, A498, Caki-2 | NA | NA | Nude Mice | NA | NA | Doxycycline selectively inhibits mitochondrial protein translation in RCC cells, causing: (1) Disruption of ETC; (2) Decreased mitochondrial respiration (↓OCR); (3) Apoptosis and reduced proliferation; and (4) Synergistic effect with paclitaxel (a chemotherapy agent) | Cell proliferation and CI measurements; measurement of apoptosis; anchorage-independent colony formation; western blot analyses; qRT-PCR; mitochondrial complex activities; Mito stress assay | Doxycycline is a useful addition to the treatment strategy for RCC, mitochondrial translation inhibition in sensitizing RCC to chemotherapy | [56] |

| 25 | BC | NA | n = 291 (TCGA and GTEx databases) | n = 1085 (TCGA and GTEx databases) | NA | MRPL1, MRPL13, MRPS6, MRPS18C, MRPS35, MRPL16, MRPL40 | MRPL1, MRPL13, MRPS6, MRPS18C, and MRPS35- upregulated; MRPL16, and MRPL40- downregulated | MRPL16 and MRPL40 were positively associated with survival outcomes, while MRPS18C and MRPS35 were inversely correlated with overall survival. MRPs are involved with cancer pathways like p21WAF1/CIP1, p27Kip1, and p53 for BC progression | Differential expression analysis; genomic alteration and methylation analysis; functional enrichment analysis and protein interaction visualization; survival analysis and prognostic model establishment | MRPs acted as biomarkers in individualized risk prediction and may serve as potential therapeutic targets in BC patients | [45] |

| 26 | BC | MCF10A (non-tumorigenic) MCF7 (ER/PR+), MDA-MB-231 (triple-negative) | NA | n = 26 | NA | MRPs (MRPS29, MRPS18B, MRPS30, and MRPL11), TSFM, TUFM | Upregulated | Downregulation of MRPs and translation factors impaired mitochondrial translation reduced OXPHOS subunit expression (especially complex I and IV) → altered mitochondrial energy metabolism. Correlation with EMT markers (↑vimentin, ↓E-cadherin) indicates promotion of metastasis and invasiveness | Immunoblotting analyses; qRT-PCR; mitochondrial complex IV activity assays | NA | [11] |

| 27 | Liver cancer | Human PLC, HepG2, MDA-MB-468, A549, MCF7, HEK293T | NA | Not given | BALB/C nude mice | GFM2 | NA | Translocated mitochondria PHGDH recruits the mitochondrial ribosome recycling factor mtEF4 via ANT2, facilitating subsequent cycles of mitochondrial translation and promoting liver cancer cell progression | RNA extraction; qRT-PCR; western blot; immunoprecipitation; mitochondria isolation, Mitochondrial translation assays; polysome profiling assay; in vitro GST pull-down assay; proliferation assay, immunofluorescence analysis; BNG; oxygen consumption measurements | NA | [41] |

| 28 | GBM | COMI and VIPI | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Inhibition of mitochondrial translation via binding to the peptidyl-transferase center of the mitoribosome. Impairment of OXPHOS complex assembly leading to GSC viability loss | Cryo-EM analysis of Q/D-mitoribosome interaction, Viability assays; mitochondrial and cytosolic protein synthesis assay, Immunoblotting; UHPLC-MS analysis | Q/D (Synercid®) is approved by the FDA for treating skin infections. The fluorine derivatives (16R)-1e, (16R)-2e, and flopristin are proposed for further in vivo testing against GBM | [40] |

| 29 | BC | MCF10A, MCF7, BT474, MDA-MB-361 | Not given | n = 89 (METABRIC datasets, TCGA tumors) | MCF7 xenografts and PDX (HCI-017), NSG mice | TUFM | NA | CBFB (through hnRNPK) binds mt-mRNAs and promotes interaction with TUFM. CBFB deficiency impairs mitochondrial translation, ETC dysfunction, ↑glycolysis (Warburg effect), ↑autophagy/mitophagy. Cells become dependent on autophagy for survival, creating a therapeutic vulnerability | Bioinformatic analyses; RIP assay, immunofluorescence staining; confocal microscopy, and super-resolution microscopy; mitochondria fractionation; in situ mitochondrial translation assay; mitochondria stress test and glycolysis stress test; flow cytometry | Combination of PI3K inhibitor (BYL719) + autophagy inhibitor (HCQ) synergistically suppressed tumor growth | [30] |

| 30 | BC | MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-436, SK-BR3 | Not given (TCGA) | Not given (TCGA) | BALB/C nude mice | mtEF4 | Upregulated | Upregulation of mtEF4 elevates the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, which contributes to the migratory capacities of breast cancer cells. mtEF4 also increases the potential of glycolysis, probably via an AMPK-related mechanism | IHC; qRT-PCR; immunoblot; extracellular flux assay; ATP measurements, Isolation of mitochondria and IGA analysis; transwell assays; GEO and TCGA datasets analysis | The aberrantly upregulated mtEF4 contributes to the metastasis of breast cancer by coordinating metabolic pathways | [61] |

| 31 | B-cell lymphoma | Control-OCI-Ly7, OCI-Ly1; | NA | NA | WT mice, B-Tfam mice (Tfam deletion in B cells); Aicda-Tfam mice (Tfam deletion in germinal center B B cells); c-Myc lymphoma model | NA | NA | TFAM regulates mitochondrial transcription and translation in germinal center B cells. Deletion of TFAM: (1) Impairs mitochondrial remodeling; (2) Disrupts actin cytoskeleton; (3) Impairs motility and spatial organization of germinal center B cells; (4) Prevents proper germinal center formation and output; and (5) Inhibits lymphoma development (c-Myc model) | Flow cytometry; confocal and STED microscopy; 5-EU incorporation (RNA synthesis); OPP labeling (mitochondrial translation); spectral flow cytometry (ETC protein profiling); single-cell RNA-seq and V(D)J sequencing; IHC; OCR; adoptive transfer experiments; TFH-B cell co-culture; ELISA for affinity maturation; iGB (induced GC B cell) culture system | TFAM expression/activity as a biomarker for germinal center b cell activation and transformation | [33] |

| 32 | AML | NA | NA | n = 41 | NA | MRPL10, MRPL22, MRPL11, MRPL54, MRPL12, MRPL16, MRPL20, MRPL24, MRPL28, MRPL38, MRPL57, MRPS18A, MRPS27 | Upregulated | NA | Data analysis | Elevated expression of mitochondrial proteins may serve as a potential indicator of relapse risk in patients with AML who have the monocytic FAB subtypes M4 and M5 | [51] |

| 33 | BC | MCF-10, MD A-MB-468, MD A-MB-453, MD A-MB-231, MCF-7 | NA | NA | BALB/C nude mice | MRPS23 | Upregulated | Promotes proliferation, migration, and EMT in breast cancer cells | Western blotting; cell migration and invasion assay; qRT-PCR; CCK-8; colony formation assay; transwell migration assays | MRPS23 can be a potential biomarker for aggressive breast cancer subtypes | [43] |

While cytosolic translation has been extensively studied, mitochondrial translation remains underexplored, especially its role in key cancer hallmarks such as sustained proliferative signaling, resistance to cell death, invasion, and metastasis. This review aims to establish a foundation for understanding mitochondrial translation in cancer and explore its potential as a therapeutic target, leveraging its unique role in tumor biology for more effective treatments.

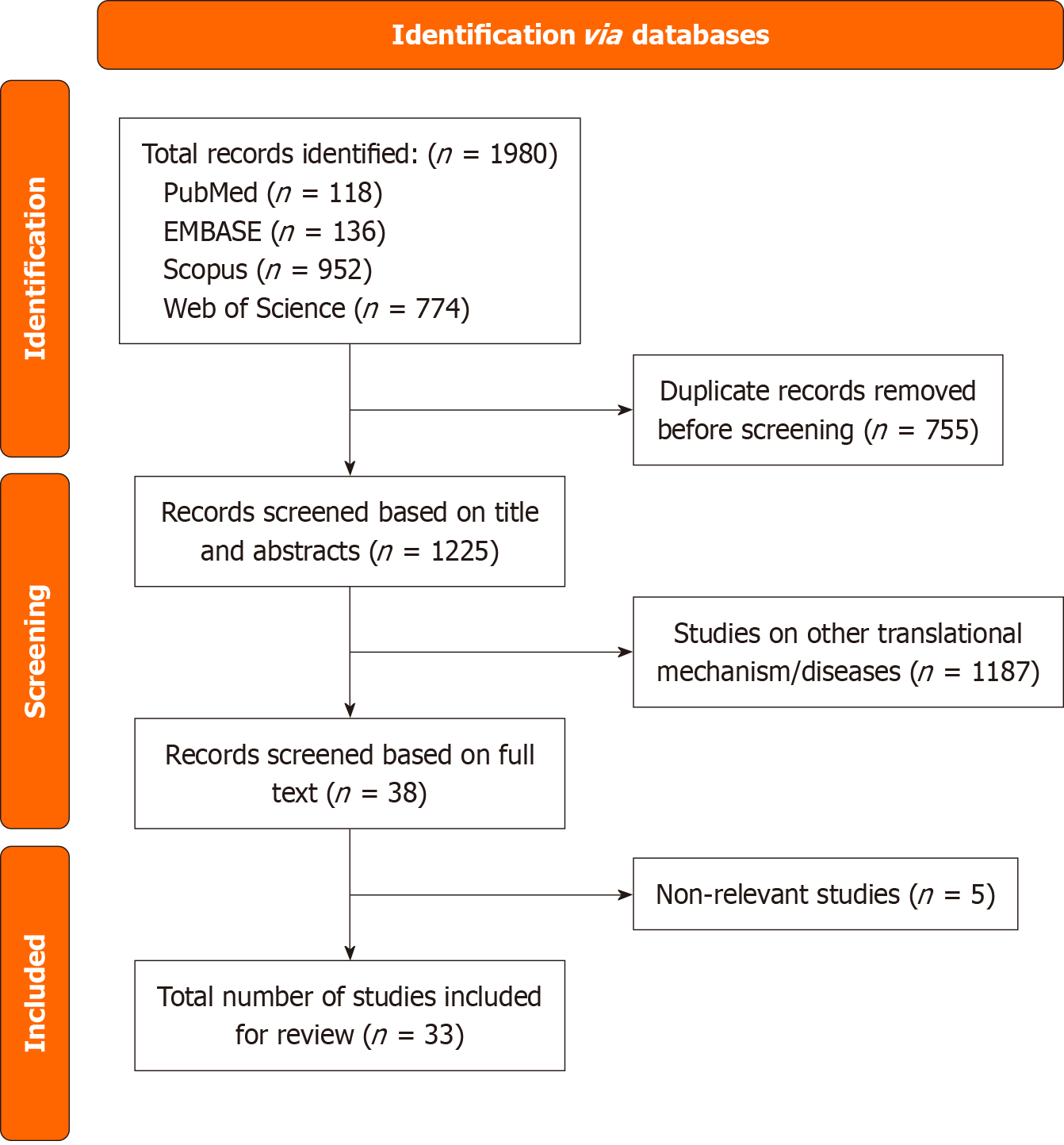

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses criteria ensured a thorough and organized synthesis of pertinent material. The literature search was conducted by the primary author (Agarwal N) under the regular supervision and direction of a senior researcher (Sharma U). A comprehensive electronic search strategy was implemented utilizing the following Boolean search string across multiple databases: [(“Cancer”) OR (“Tumor”) OR (“Carcinoma”) OR (“Malignancy”) OR (“Neoplasm”) OR (“Sarcoma”) OR (“Lymphoma”) OR (“leukemia”)] AND (“Mitochondrial translation”). The search was limited to publications indexed between March 2014 and February 2025. In the primary literature search, detailed information was retrieved from Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and EMBASE, accessed on April 7, 2025. Initial screening of retrieved records was based on title and abstract evaluation. Following a rigorous selection process, 1225 articles met the inclusion criteria, as depicted in Figure 1.

Only original research articles that addressed mitochondrial translation in various malignancies were taken into consideration due to our strict inclusion criteria. Several studies were found by an initial thorough web search; duplicate entries were removed from these studies (n = 755) to get rid of redundant information. Furthermore, during the database search, non-primary research sources were eliminated. Among these removed materials were review articles, abstracts from conferences, book chapters, encyclopedias, meta-analyses, patents, and grey literature. Articles that discussed other translational mechanisms or disorders or that just had a passing connection to mitochondrial translation were also disqualified from this review (n = 1192). Lastly, the review included (n = 33) peer-reviewed original research articles that satisfied the inclusion requirements. These selected studies provide critical insights into the role of mitochondrial translation in cancer, reveal potential therapeutic targets across diverse tumor types, and propose innovative strategies to overcome treatment resistance.

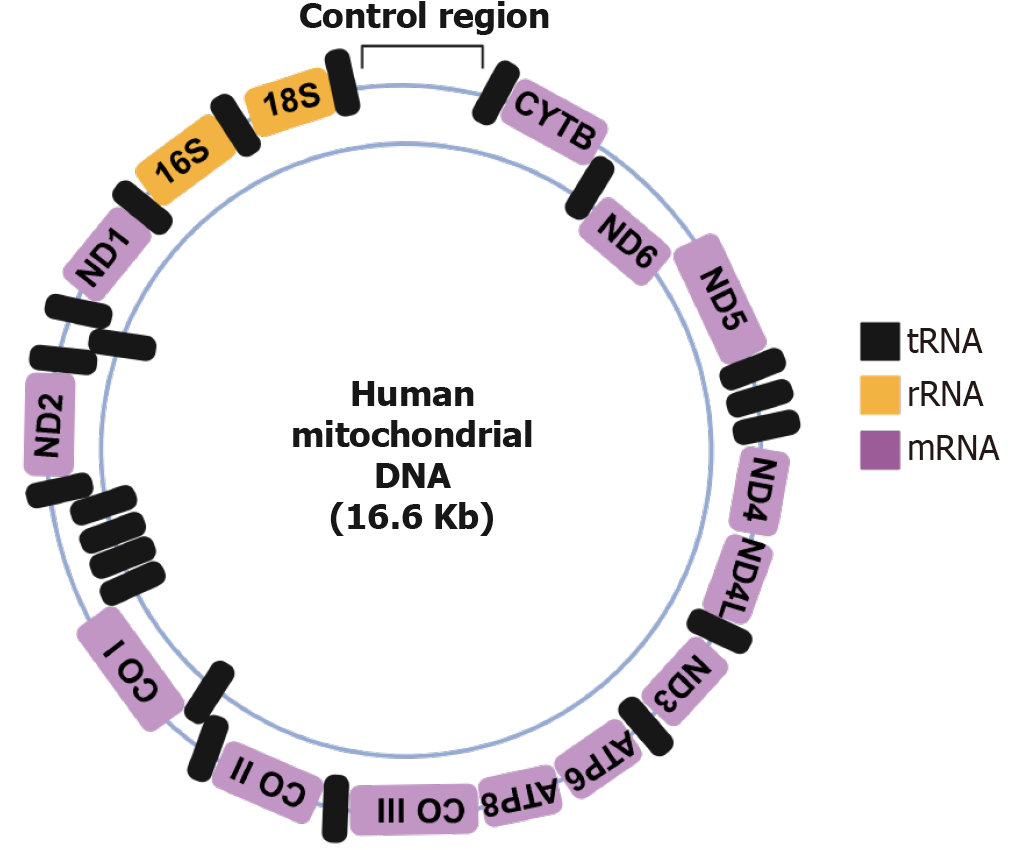

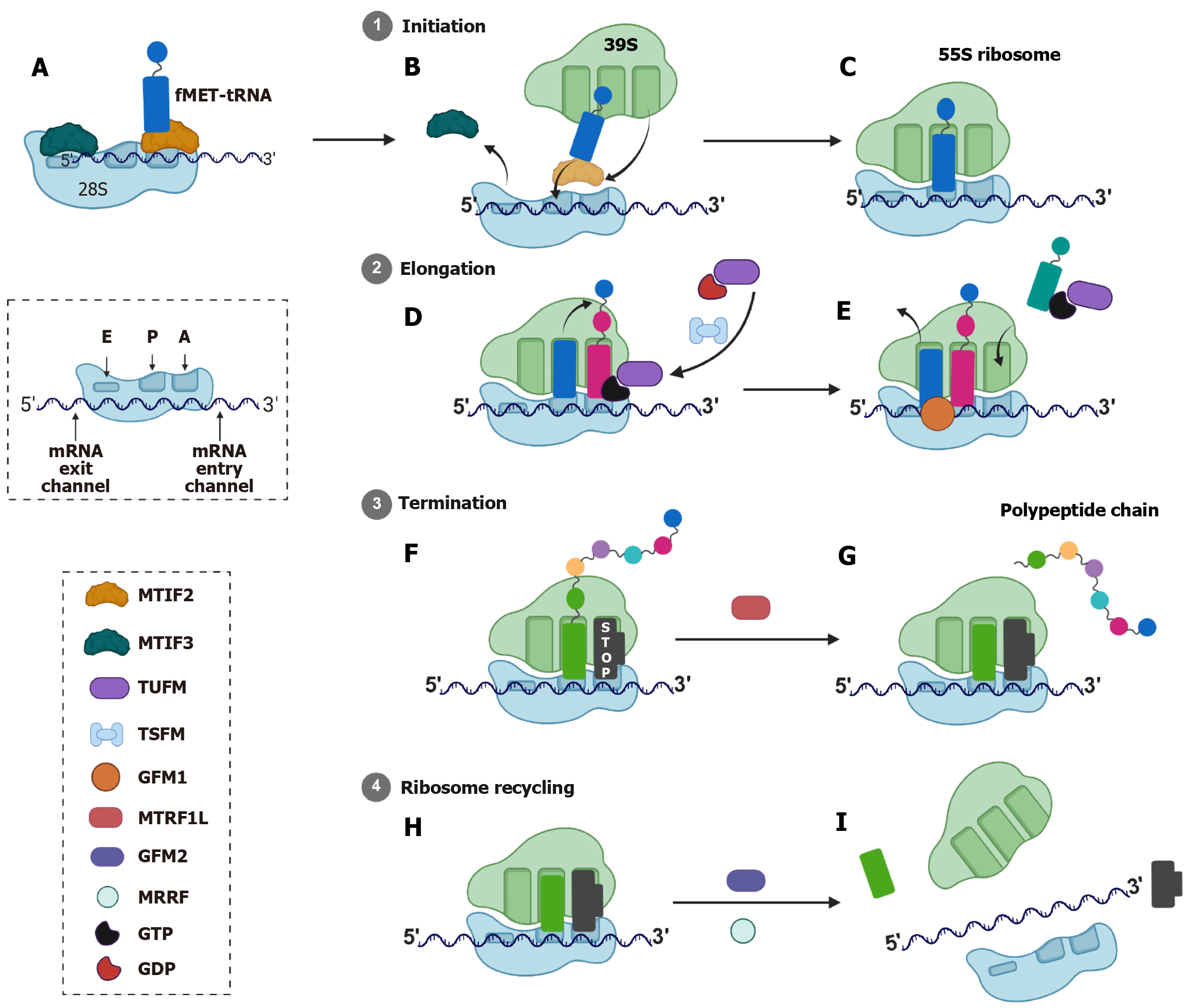

Mitochondrial translation is the process by which mitochondria synthesize proteins encoded by its own mtDNA. This process is essential for the proper functioning of the OXPHOS system, which is responsible for ATP production in eukaryotic cells[16]. Human mtDNA encodes for 13 essential polypeptides, all of which are integral components of the OXPHOS complexes. Additionally, mtDNA encodes 22 tRNAs and 2 rRNAs necessary for mitochondrial protein synthesis, as shown in Figure 2[4,16]. The mitochondrial translation takes place in the matrix of the mitochondrion and is performed by dedicated machineries, such as the mitochondrial ribosome (mitoribosome), tRNAs, and translation factors[4]. The proteins required for assembly of mitoribosomes and the translation factors are encoded by nuclear DNA and are imported into mitochondria, whereas the rRNAs and tRNAs are encoded by mtDNA. These mitoribosomes differ structurally from cytoplasmic ribosomes, as mitoribosomes are composed of a small 28S subunit and a large 39S subunit, forming a 55S ribosome, whereas cytoplasmic ribosomes are composed of smaller 40S subunits and larger 60S subunits, forming an 80S ribosome. Also, mitoribosomes have 2 rRNAs (16S and 12S) compared to cytoplasmic ribosomes which have 4 rRNAs (28S, 5.8S, 5S and 18S; Figure 3). The mitoribosomes are made up of unique proteins known as MRPs which are absent in cytoplasmic ribosomes. These MRPs are nuclear-encoded and form the protein scaffold of mitochondrial ribosomes and also play roles in ribosome assembly and rRNA stabilization[17]. The MRPs of larger subunit are denoted as MRPL (approximately 50 proteins) and of smaller subunit are denoted by MRPS (approximately 30 proteins). Unlike cytoplasmic translation, which involves complex regulatory mechanisms, mitochondrial translation relies on fewer initiation factors and simpler messenger RNA (mRNA) structures[4,18].

Mitochondrial translation occurs in four main stages: Initiation, elongation, termination, and ribosome recycling. The initiation phase involves assembling the 28S small subunit with formylmethionyl-tRNA for methionine, mRNA, and two initiation factors, MTIF2 and MTIF3, as illustrated in Figure 3[4,18]. Unlike bacterial or cytoplasmic systems, mitochondrial initiation does not require a third factor [e.g., initiation factor 1 in bacteria or eukaryotic initiation factor 1 in cytoplasmic translation]. The formylation of the methionine residue plays a crucial role in mitochondrial translation, as it is necessary for MTIF2 to increase its affinity for tRNA as MTIF2 binds directly to the formylmethionyl-tRNA for methionine, stabilizing its interaction with the small subunit, as illustrated in Figure 3. This feature is not present in cytoplasmic translation as it is not required[4,18]. Notably, MTIF2 possesses a unique 37-amino acid insertion domain that mimics the bacterial initiation factor 1, blocking the aminoacyl (A) site of the ribosome during initiation, as shown in Figure 3[18]. This insertion domain ensures proper positioning of formylmethionyl-tRNA for methionine and prevents premature elongation[18]. MTIF3 facilitates the correct positioning of the AUG initiation codon within the peptide (P) site of the small subunit. It stabilizes the mRNA-small subunit interaction and prevents premature binding of elongation factors[16]. Cryogenic electron microscopy studies reveal that MTIF3 interacts with the mitoribosomal protein mito

Next is elongation, which involves tRNA binding, peptide bond formation, and ribosomal translocation. Mitochondrial elongation factors include TUFM, mitochondrial elongation factor Ts (TSFM), and GFM1[4,20]. TUFM delivers am

Translation termination in mitochondria is mediated by mitochondrial release factor. Human mitochondria contain four members of the class 1 release factor family: Mitochondrial release factor (MTRF) 1A (MTRF1 L), MTRF1, MTRF in rescue (previously known as C12orf65), and MRPL58 (previously known as immature colon carcinoma transcript 1)[24]. MTRF1 and MTRF1 L recognize stop codons and trigger peptide release from the P site tRNA, as shown in Figure 3[25]. There are two types of stop codons in mitochondria, canonical (UAA, UAG) and non-canonical (AGA, AGG), whereas the cytoplasm has canonical stop codons (UAG, UGA and UAA). These non-canonical codons are unique to mitochondria because they lack cognate tRNAs in the mitochondrial translation system, having been reassigned from their usual arginine-coding function. The AGA codon is located at the end of cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene whereas AGG is located at the end of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydrogen dehydrogenase subunit 6 gene[26]. MTRF1 L recognizes canonical stop codons UAA and UAG and is responsible for terminating translation of 11 out of 13 mitochondrial proteins[27,28]. It contains a conserved codon recognition domain similar to bacterial release factor 1 and utilizes direct base-specific interactions with mRNA stop codons[26,27]. On the other hand, MTRF1 specifically recognizes and terminates translation at non-canonical stop codons AGA and AGG. It contains specific insertions in the codon recognition domain not found in MTRF1 L[26,27]. This extended codon recognition loop pushes the first two bases (AG) of the stop codon toward the head region of the small ribosomal subunit and creates a unique binding mode where the stop codon is repositioned rather than directly contacted[26,27].

Finally, ribosome recycling separates the mitoribosomal subunits (28S and 39S) and releases mRNA/tRNA, enabling reinitiation. This process is facilitated by mitochondrial elongation factor G2 (GFM2) and MRRF, as depicted in Figure 3[29]. GFM2 promotes the dissociation of the subunits through guanosine triphosphate hydrolysis, in contrast to the ATP hydrolysis seen in cytoplasmic ribosome recycling. GFM1 interacts with MRRF, which binds to the A site, enabling the release of mRNA/tRNA, as illustrated in Figure 3. Unlike GFM1, GFM2 does not possess the structural motifs necessary for translocation and instead specializes in the recycling process[29].

Mitochondrial translation is optimized for synthesizing OXPHOS components. Its structural simplicity (leaderless mRNAs, fewer initiation factors) contrasts with the complexity of cytoplasmic translation, which requires scanning, capping, and extensive regulatory machinery[5,16]. Understanding these distinctions provides critical insights into mitochondrial biology, disease mechanisms, and evolutionary adaptation[4].

Mitochondrial translation and its regulatory parameters play a vital role in numerous fundamental features of cancer, such as persistent proliferation, resistance to apoptosis, and the ability to invade and metastasise[10,30]. Cancer cells demand enhanced generation of ATP and anabolic support, which are both strongly linked to the activity of mitoch

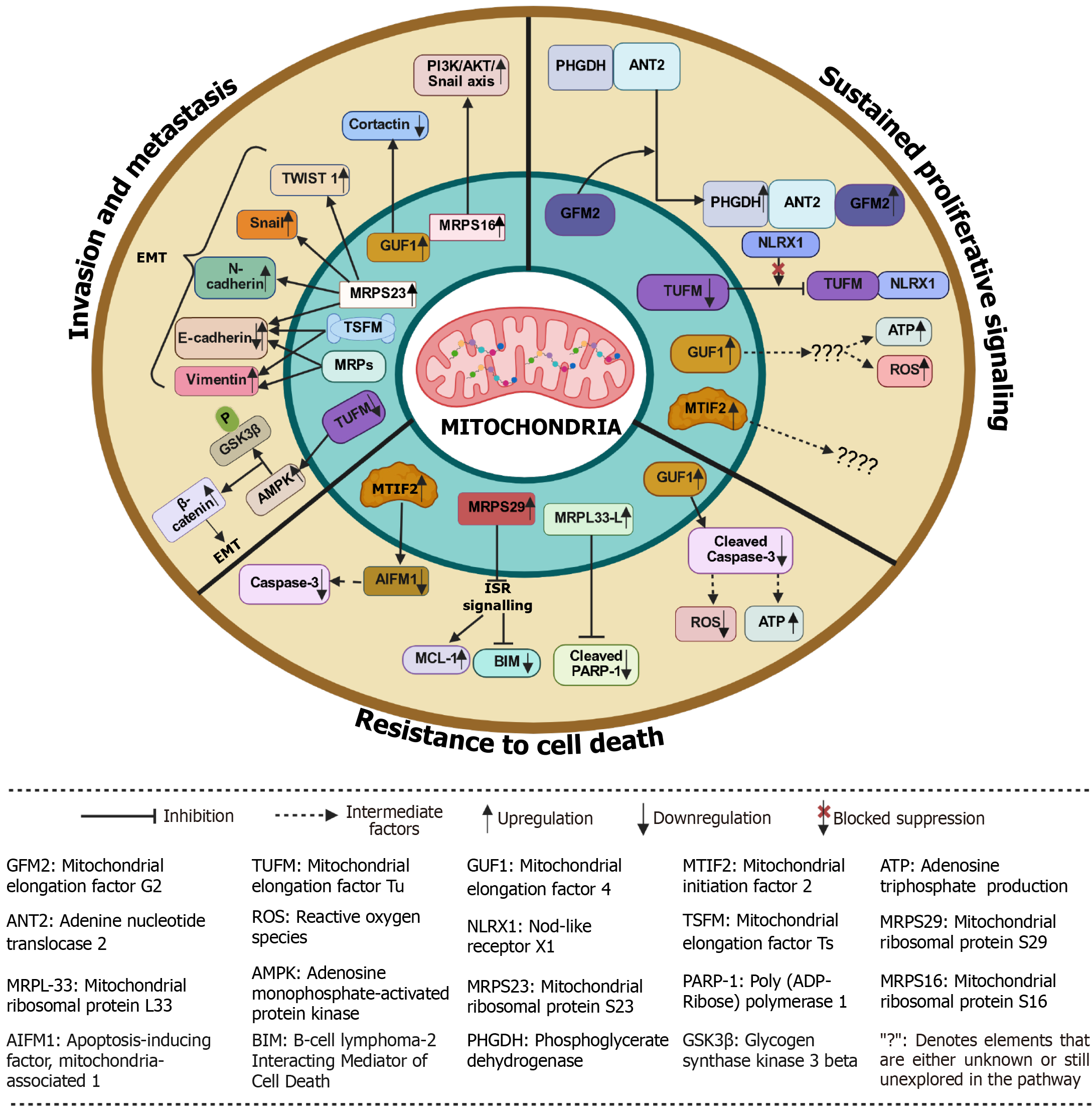

Sustained proliferative signaling refers to the ability of cancer cells to continuously receive and transmit growth signals, which enables them to divide uncontrollably. These proliferating cells depend on large amounts of ATP and biosynthetic precursors, both of which are produced by functional mitochondria[10]. Efficient mitochondrial translation is crucial as it supplies ATP through OXPHOS and provides the necessary building blocks for cellular anabolism[31]. The dysregulated mitochondrial translation factors play a significant role in supporting cancer cell proliferation across various tumor types by driving metabolic reprogramming and bypassing cellular checkpoints[30]. For example, TUFM is highly expressed in PCI-13 and UDSCC2 (HNSCC cell lines), and it forms a mitochondrial complex along with nod-like receptor X1 that triggers autophagy and counters anti-proliferative effects in HNSCC cells[34]. Also, the upregulation of TUFM protein is associated with the progression of colorectal cancer through colorectal adenoma-to-carcinoma transformation and correlates with poor clinical outcomes, suggesting that TUFM could serve as an important prognostic factor for cancer patients[35]. The knockdown of TUFM along with tigecycline treatment in renal cell carcinoma cells leads to reduced cell growth and survival as a consequence of the suppression of essential growth/ survival signaling pathway phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT)/mTOR, as illustrated in Figure 4 and Table 1[36].

Emerging studies have used anti-TUFM nanobodies (Nb206) to target TUFM in glioblastoma multiforme, as TUFM is highly expressed in glioblastoma multiforme cell lines [U87MG, U251MG and glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs)] compared to neural stem cells[37]. Nb206 significantly inhibited the proliferation of U87MG and GSCs in a dose-dependent manner[37]. Similar results were found with Nb225 anti-TUFM nanobody in glioblastoma[38]. In GISTs, it was found with the help of the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay that the knockdown of TUFM inhibited the proliferation rate of GIST cells[9]. In breast cancer, with the help of the Ki67 assay, it was observed that impairing mitochondrial translation by knocking down core binding factor beta led to reduced proliferation of MCF10A cells[30]. Furthermore, the researchers evaluated the effect of knocking out the TUFM and MRPS18A genes on GSCs that were grown as glioma spheres. The size of glioma spheres was measured over 15 days, and the results showed a significant reduction in the size of the glioma spheres in the TUFM and MRPS18A knockout cells compared to the normal cells[39,40]. In another study, with the help of tumor formation assay it was found that elevated expression of mtEF4 increases the production of respiratory chain complexes and levels of both ATP and ROS in cells, which leads to increased cellular proliferation in lung, cervical, esophageal, and bladder cancers[10]. In liver cancer, depletion of GFM2 expression reduces phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH) mediated tumor growth[41]. Mechanistically, PHGDH forms a complex with adenine nucleotide translocase 2 to recruit GFM2. This recruitment promotes the efficiency of mitochondrial ribosome recycling, mito

In colorectal cancer, MRPL33-L can promote cancer cell growth, as its knockdown in SW620 and HT29 colon cancer cells showed growth repression, observed by colony forming assay[46]. Furthermore, the expression of MRPL11 was found to be 2-fold decreased in HN8 cells (HNSCC cell line) compared to HaCat cells (normal cell line) and a reduced expression of MRPL11 was observed in some patients of HNSCC[13]. This impairment in mitochondrial translation due to reduced expression of MRPL11 Leads to defective synthesis of mitochondrial-encoded proteins (e.g., subunit of complex IV), which in turn impairs OXPHOS[13]. This defect potentially forces a metabolic shift to aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect), aiding tumor survival and progression, particularly in metastatic sites[13]. MRPS16 is highly expressed in glioblastoma, and its over-expression in U-138MG cells using lentiviruses leads to enhanced tumor cell growth measured by CCK-8, EdU, colony formation, and transwell and vice versa in MRPS16 knockdown cells[32]. Notably, with the help of dual luciferase reporter assays, it was confirmed that knockdown of MRPS16 inhibits PI3K/AKT signaling (Table 1)[32]. Additionally, Snail, phosphorylated-AKT and phosphorylated-PI3K protein levels were found to be significantly decreased in MRPS16 knockdown cells, as shown by western blot. These findings demonstrated that MRPS16 facilitates tumor development through the PI3K/AKT/Snail pathway[32]. A recent study showed that mito

These observations highlight the mitochondrial translation machinery as a vital player in cancer metabolism, presenting new avenues for targeted therapies aimed at inhibiting factors such as MTIF2, TUFM, mtEF4, GFM2, MRPS16, or MRPS23 to disrupt cancer cell proliferation. These factors enable metabolic reprogramming that bypasses cellular checkpoints, with TUFM overexpression correlating with poor clinical outcomes in colorectal cancer progression and reduced cell survival when inhibited across multiple cancer types including glioblastoma, breast, and liver cancers. The dysregulation of MRPs like MRPS23, MRPL33, and others demonstrates their dual role in promoting tumor growth while offering potential therapeutic targets, as their knockdown consistently reduces proliferation rates and tumor formation across various cancer models. Collectively, these mitochondrial translation components represent both prognostic biomarkers and promising therapeutic vulnerabilities in cancer treatment strategies.

Resistance to apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death, is a hallmark characteristic of cancer cells and significantly contributes to the progression and survival of tumors[46]. This resistance allows cancerous cells to evade the normal regulatory processes that trigger cell death in response to various stressors, including DNA damage and oxidative stress. Recent research has highlighted the potential of targeting mitochondrial translation as a therapeutic strategy to induce apoptosis in these resistant cancer cells. Like, in glioblastoma multiforme, researchers have used NB206 nanobody to target TUFM, and they found that there was a significant reduction in the cell viability at 100 μg/mL Nb206 after 48 hours of incubation in GSCs, U87MG and U251MG (Table 1)[37]. Similarly, Nb225 nanobody also showed a significant increase in apoptosis, as illustrated in Figure 4 and Table 1[38]. In another study, it was found that low mtEF4 levels increase mitochondrial translation but decrease translational fidelity[10]. As a result, the respiratory chain complexes produced are of low quality, which may lead to less ATP and more ROS. All these changes increase the risk of apoptosis in lung, cervical, esophageal, and bladder cancers as observed by the increased levels of cleaved caspase-3 in the cells, which were knocked down for mtEF4, as shown in Figure 4 and Table 1[10]. Also, MTIF2 suppression enhances apoptosis in HCC by modulating interactions with the apoptosis-inducing factor apoptosis-inducing factor mitochondria-associated (AIFM) 1, as MTIF2 normally binds directly to AIFM1 in the mitochondrial intermembrane space, blocking AIFM1’s pro-apoptotic functions. The knockdown of MTIF2 frees AIFM1 allowing it to undergo calpain-mediated cleavage and translocate to the nucleus where it facilitates large-scale DNA fragmentation and acts as a transcriptional co-activator for the caspase 3 gene promoter, increasing caspase 3 mRNA and protein levels, as shown in Figure 4 and Table 1[42,49]. And in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL), GFM1, TUFM, and MRPS7 were depleted using short hairpin RNAs in oxidative phosphorylation- and non-oxidative phosphorylation/B-cell receptor-DLBCL cell lines, and found a significant cell death in OXPHO-DLBCL cells compared to non-OxPhos/B-cell receptor-DLBCL (Table 1)[50].

Studies reveal widespread dysregulation of MRPs, including smaller (MRPS) and larger (MRPL) subunit genes, across diverse malignancies such as renal cell carcinoma, ovarian cancer, osteosarcoma, glioblastoma, breast cancer, and acute myeloid leukemia[36,46,39,51-54]. In acute myeloid leukemia, knockdown of DAP3 (MRPS29) along with venetoclax leads to apoptosis induction. This happens because it activates a response called the integrated stress response. This response can lead to an increase in the production of proteins that cause cell death, such as B-cell lymphoma 2 interacting mediator of cell death, while lowering levels of proteins that protect against cell death, like myeloid cell leukemia 1. This process makes the cells more likely to undergo apoptosis 52]. Also, the knockdown of MRPL33-L in SW620 and HT29 colon cancer cells significantly activates apoptosis, as indicated by the presence of cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1, a known apoptosis marker[46]. In breast cancer cells and renal cell carcinoma cells, by using doxycycline mitochondrial translation was inhibited, leading to cancer cell death as doxycycline blocks the A-site of tRNA on 28S small subunit of mitoribosome[55,56]. Furthermore, in breast cancer cells, DEAD box RNA helicase (DDX3) is inhibited by RK-33. DDX3 plays a role in mitochondrial homeostasis by translocating to mitochondria where in response to mitochondrial stress, it facilitates the translation of phosphatase and tensin homology-induced kinase 1[57]. Inhibition of DDX3 suppresses mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy, which leads to increased ROS and apoptosis due to a reduction in Mitochondrial-encoded proteins expression, OXPHOS capacity and ATP production, as illustrated in Figure 4 and Table 1[54].

Tigecycline also acts on mitochondrial ribosomes by blocking the A-site of tRNA on 28S small subunit, leading to the inhibition of mitochondrial translation[58,59]. In ovarian cancer cells treated with tigecycline, researchers observed a notable reduction in both basal and maximal mitochondrial respiration, along with an increase in cellular levels of ROS and the oxidative DNA damage marker 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine[58]. Additionally, there was an elevation in phosphorylated adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and a decrease in phosphorylated mTOR in the tigecycline-treated cells as inhibition of mitochondrial translation by tigecycline impairs electron transport chain function, leading to an increased adenosine monophosphate/ATP ratio that allosterically activates AMPK. Furthermore, activated AMPK phosphorylates key components of the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 pathway, leading to the inhibition of mTOR signaling pathway[60]. This suggests that tigecycline activates AMPK and suppresses mTOR signaling as a result of mitochondrial dysfunction leading to increased apoptosis[58]. Similarly, in osteosarcoma, tigecycline and knockdown of TUFM selectively inhibit mitochondrial translation, impair mitochondrial respiration and induce apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells, as shown in Figure 4 and Table 1[53]. Collectively, aberrant expression of mitochondrial translation factors and MRPs fosters resistance to cell death, enabling tumor persistence. Targeting these components could disrupt mitochondrial function, amplify oxidative stress, impair energy production, activate integrated stress response, and reduce pro-survival signaling, ultimately tipping the balance toward cancer cell death.

Invasion and metastasis remain key hallmarks of cancer progression, often determining patient prognosis and therapeutic outcomes. Recent evidence suggests that mitochondrial function, particularly mitochondrial translation, plays a critical role in driving these aggressive phenotypes. In lung cancer and breast cancer, it was observed that knockdown of TUFM triggered EMT, decreased the activity of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, and enhanced glycolytic activity along with the generation of ROS[31]. From a mechanistic perspective, TUFM knockdown activated AMPK, leading to the phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β and increased the nuclear presence of β-catenin, which resulted in the promotion of EMT and increase in migration and metastasis of A549 Lung cancer cells and MCF7 breast cancer cells, as evaluated by the increased levels of E-cadherin, and decreased levels of N-cadherin, and fibronectin[31]. Also, in GISTs, the expression of TUFM is positively correlated with the risk of tumor metastasis[9]. The wound healing assays showed that silencing TUFM significantly reduced the migratory rate of GIST-T1 and GIST-IR cells compared to the control groups after 48 hours of transfection, as illustrated in Figure 4 and Table 1[9].

In breast cancer, the downregulation of translation factors (TUFM and TSFM) and MRPs (DAP3, MRPS18B, MRPS30, and MRPL11) impairs mitochondrial translation, which leads to reduced OXPHOS subunit expression (especially Complex I and IV) and altered mitochondrial energy metabolism[11]. These changes correlate with EMT markers (↑Vimentin, ↓E-cadherin), indicating promotion of metastasis and invasiveness, as shown in Figure 4 and Table 1[11]. Furthermore, functionally, mtEF4 promotes the assembly of mitochondrial respiratory complexes, enhancing OXPHOS and ATP production (Table 1)[61]. This increase in cellular energy supports the formation of lamellipodia and actin cytoskeleton remodeling, structures essential for cell motility and invasion[61]. It is observed that when mitochondrial translation becomes dysregulated, cells respond with dramatic cytoskeletal reorganization[62]. Mitochondrial dysfunction triggers rapid actin polymerization around damaged organelles, mediated by the actin-related protein 2/3 complex and occurs within minutes of mitochondrial damage and promoting glycolytic activation. This rapid response helps cells compensate for impaired OXPHOS by enhancing cytoplasmic glucose metabolism[62]. In breast cancer, knockdown of mtEF4 not only disrupts these cytoskeletal changes (checked by expression of cortactin) but also impairs migration and invasion in vitro and significantly reduces metastatic burden in MDA-MB-231 cells (assessed by transwell membrane assay)[61]. Also, overexpression of MRPS23 leads to increased migration and invasion of breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) after 48 hours of incubation compared to the control group, assessed by scratch and wound healing assay[43]. And, the knockdown of MRPS23 leads to the reduced expression of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Snail1 and TWIST1, which indicates silencing of MRPS23 attenuates the EMT process[43]. In gliomas, overexpression of MRPS16, an MRP, activates the PI3K/AKT/Snail axis, a well-established pathway driving EMT and metastasis. Silencing MRPS16 reduces cell migration and invasion, further supporting the role of mitochondrial translation machinery in promoting tumor aggressiveness[32]. And finally, as mentioned earlier in sections 4.1 and 4.2, since MTIF2 is significantly expressed in HCC, the impact of downregulating MTIF2 levels on the migration of HCC cells was checked through a wound healing assay and a transwell assay. The findings revealed that downregulation of MTIF2 also impaired the migratory ability of HCC cells, as illustrated in Figure 4 and Table 1[42]. In summary, the accumulating evidence underscores a critical link between mitochondrial translation and cancer metastasis across multiple tumor types. Disruption of mitochondrial translation factors such as TUFM, TSFM, mtEF4, and various MRPs alters mitochondrial respiration. This impairment may then facilitate EMT via the AMPK/glycogen synthase kinase-3β signaling pathway. Additionally, these disruptions lead to cytoskeletal remodeling through the actin-related protein 2/3 complex, which is responsible for actin polymerization. As a result, cancer cells may exhibit enhanced migratory and invasive capabilities through the activation of path

All these findings suggest that mitochondrial translation is not merely a metabolic process but a central regulator of the cancer hallmarks (sustained proliferative signaling, resistance to apoptosis and invasion and metastasis), likely through interconnected pathways involving energy metabolism, ROS signaling, cytoskeletal remodeling, and EMT transcriptional programs. Firstly, sustained proliferation is driven by overexpression of factors such as TUFM, mtEF4 and MRPS23, which enhance OXPHOS-derived ATP and biosynthetic precursors to fuel cell division, with inhibition via tigecycline, nanobodies or genetic knockdown consistently reducing tumor growth. Secondly, resistance to apoptosis arises when impaired translation factors (e.g., MTIF2, GFM1, MRPS16) disrupt mitochondrial membrane potential and ROS/AMPK signaling, thereby blocking intrinsic death pathways, while restoring their function or targeting them reactivates caspase-dependent cell death. Finally, invasion and metastasis are promoted by translational defects that alter cytoskeletal dynamics and EMT programs, driven by mtEF4, MRPS16 and MRPL11, enabling motility and colonization, whereas correcting translational imbalance impairs migratory and invasive behavior. Thus, targeting components of the mito

The intricate regulation of mitochondrial translation plays a pivotal role in orchestrating core hallmarks of cancer, including sustained proliferation, resistance to cell death, and enhanced metastatic potential. Although mitochondrial metabolism has long been recognized as a key player in oncology, the specific contributions of translational regulation have remained underexplored. This review has systematically delineated how dysregulation of mitochondrial translation factors and mitoribosomal proteins drives metabolic reprogramming, compromises apoptotic checkpoints via ROS/AMPK and PI3K/AKT pathways, and facilitates cytoskeletal remodeling and EMT, thereby promoting sustained proliferation, resistance to cell death and enhanced invasion. Importantly, context-dependent defects reveal that certain cancers exploit distinct translational vulnerabilities, for instance, MRPL11 downregulation in HNSCC shifts cells toward aerobic glycolysis, TUFM overexpression in colorectal adenoma-to-carcinoma progression correlates with poor prognosis, and mtEF4 knockdown in lung adenocarcinoma reroutes bioenergetics toward glycolysis. Preclinical evidence underscores the therapeutic promise of selectively targeting mitochondrial translation, tigecycline or anti-TUFM nanobodies curtail glioblastoma growth, GFM2 depletion attenuates PHGDH-driven hepatocarcinogenesis, and MRPS23 knockdown impairs HCC proliferation. These findings validate mitochondrial translation components as actionable vulnerabilities and position MRPs as prognostic biomarkers for patient stratification.

Looking forward, a deeper mechanistic understanding of how mitochondrial translation interfaces with oncogenic signaling, immune modulation, and therapy resistance remains a pressing need. Future studies should focus on delineating the context-specific roles of mitochondrial translation factors across diverse tumor types and stages. This could be achieved through multi-omics integration, high-resolution structural biology, and the development of in vivo models that faithfully recapitulate human mitochondrial dysfunction in cancer. Furthermore, prioritizing high-resolution mapping of mitoribosome factor interactions in diverse tumor contexts to uncover tumor-specific vulnerabilities and guide the design of high-affinity, cell-permeable inhibitors or degraders against key translation factors. Rigorous assessment of on-target mitochondrial toxicity and potential resistance mechanisms will be critical to advancing these agents toward clinical translation. Integrating mitochondrial translation profiling into genomic and proteomic pipelines can further refine predictive biomarkers, enabling personalized therapeutic approaches. Finally, dissecting compensatory signaling networks, such as AMPK/mTOR and BDNF/FAO axes, activated upon translational blockade will preempt adaptive resistance and inform rational combination regimens. By consolidating mechanistic insights and preclinical validations, this review provides a focused framework for advancing mitochondrial translation from a conceptual hallmark to a clinically actionable vulnerability in cancer therapy, thereby adding significant value to the scientific community’s efforts to develop targeted, metabolism-based treatments.

| 1. | Iyer P, Jasdanwala SS, Bhatia K, Bhatt S. Mitochondria and Acute Leukemia: A Clinician's Perspective. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:9704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vyas S, Zaganjor E, Haigis MC. Mitochondria and Cancer. Cell. 2016;166:555-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 871] [Cited by in RCA: 1318] [Article Influence: 131.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chaudhary S, Ganguly S, Singh A, Palanichamy JK, Chopra A, Bakhshi R, Bakhshi S. Mitochondrial complex II and V activity is enhanced in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Blood Res. 2021;11:534-543. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Wang F, Zhang D, Zhang D, Li P, Gao Y. Mitochondrial Protein Translation: Emerging Roles and Clinical Significance in Disease. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:675465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lightowlers RN, Rozanska A, Chrzanowska-Lightowlers ZM. Mitochondrial protein synthesis: figuring the fundamentals, complexities and complications, of mammalian mitochondrial translation. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:2496-2503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tyagi A, Pramanik R, Bakhshi R, Singh A, Vishnubhatla S, Bakhshi S. Expression of mitochondrial genes predicts survival in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Int J Hematol. 2019;110:205-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Singh R, Jain A, Palanichamy JK, Nag TC, Bakhshi S, Singh A. Ultrastructural changes in cristae of lymphoblasts in acute lymphoblastic leukemia parallel alterations in biogenesis markers. Appl Microsc. 2021;51:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | D'Andrea A, Gritti I, Nicoli P, Giorgio M, Doni M, Conti A, Bianchi V, Casoli L, Sabò A, Mironov A, Beznoussenko GV, Amati B. The mitochondrial translation machinery as a therapeutic target in Myc-driven lymphomas. Oncotarget. 2016;7:72415-72430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Weng X, Zheng S, Shui H, Lin G, Zhou Y. TUFM-knockdown inhibits the migration and proliferation of gastrointestinal stromal tumor cells. Oncol Lett. 2020;20:250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhu P, Liu Y, Zhang F, Bai X, Chen Z, Shangguan F, Zhang B, Zhang L, Chen Q, Xie D, Lan L, Xue X, Liang XJ, Lu B, Wei T, Qin Y. Human Elongation Factor 4 Regulates Cancer Bioenergetics by Acting as a Mitochondrial Translation Switch. Cancer Res. 2018;78:2813-2824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Koc EC, Koc FC, Kartal F, Tirona M, Koc H. Role of mitochondrial translation in remodeling of energy metabolism in ER/PR(+) breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2022;12:897207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bacon JM, Jones JL, Liu GS, Dickinson JL, Raspin K. Mitochondrial ribosomal proteins in metastasis and their potential use as prognostic and therapeutic targets. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2024;43:1119-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Koc EC, Haciosmanoglu E, Claudio PP, Wolf A, Califano L, Friscia M, Cortese A, Koc H. Impaired mitochondrial protein synthesis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mitochondrion. 2015;24:113-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pu M, Wang J, Huang Q, Zhao G, Xia C, Shang R, Zhang Z, Bian Z, Yang X, Tao K. High MRPS23 expression contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation and indicates poor survival outcomes. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317709127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhuang L, Meng Z, Yang Z. MRPL27 contributes to unfavorable overall survival and disease-free survival from cholangiocarcinoma patients. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18:936-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kummer E, Ban N. Mechanisms and regulation of protein synthesis in mitochondria. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:307-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 46.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Scaltsoyiannes V, Corre N, Waltz F, Giegé P. Types and Functions of Mitoribosome-Specific Ribosomal Proteins across Eukaryotes. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:3474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yassin AS, Haque ME, Datta PP, Elmore K, Banavali NK, Spremulli LL, Agrawal RK. Insertion domain within mammalian mitochondrial translation initiation factor 2 serves the role of eubacterial initiation factor 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3918-3923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jackson RJ, Hellen CU, Pestova TV. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:113-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1766] [Cited by in RCA: 2105] [Article Influence: 131.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kummer E, Ban N. Structural insights into mammalian mitochondrial translation elongation catalyzed by mtEFG1. EMBO J. 2020;39:e104820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bauerschmitt H, Funes S, Herrmann JM. The membrane-bound GTPase Guf1 promotes mitochondrial protein synthesis under suboptimal conditions. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17139-17146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu L, Shao M, Huang Y, Qian P, Huang H. Unraveling the roles and mechanisms of mitochondrial translation in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. J Hematol Oncol. 2024;17:95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liu H, Pan D, Pech M, Cooperman BS. Interrupted catalysis: the EF4 (LepA) effect on back-translocation. J Mol Biol. 2010;396:1043-1052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Akabane S, Ueda T, Nierhaus KH, Takeuchi N. Ribosome rescue and translation termination at non-standard stop codons by ICT1 in mammalian mitochondria. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nadler F, Lavdovskaia E, Krempler A, Cruz-Zaragoza LD, Dennerlein S, Richter-Dennerlein R. Human mtRF1 terminates COX1 translation and its ablation induces mitochondrial ribosome-associated quality control. Nat Commun. 2022;13:6406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Krüger A, Kovalchuk D, Shiriaev D, Rorbach J. Decoding the Enigma: Translation Termination in Human Mitochondria. Hum Mol Genet. 2024;33:R42-R46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Soleimanpour-Lichaei HR, Kühl I, Gaisne M, Passos JF, Wydro M, Rorbach J, Temperley R, Bonnefoy N, Tate W, Lightowlers R, Chrzanowska-Lightowlers Z. mtRF1a is a human mitochondrial translation release factor decoding the major termination codons UAA and UAG. Mol Cell. 2007;27:745-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kaji A, Kiel MC, Hirokawa G, Muto AR, Inokuchi Y, Kaji H. The fourth step of protein synthesis: disassembly of the posttermination complex is catalyzed by elongation factor G and ribosome recycling factor, a near-perfect mimic of tRNA. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2001;66:515-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Seely SM, Gagnon MG. Mechanisms of ribosome recycling in bacteria and mitochondria: a structural perspective. RNA Biol. 2022;19:662-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Malik N, Kim YI, Yan H, Tseng YC, du Bois W, Ayaz G, Tran AD, Vera-Ramirez L, Yang H, Michalowski AM, Kruhlak M, Lee M, Hunter KW, Huang J. Dysregulation of Mitochondrial Translation Caused by CBFB Deficiency Cooperates with Mutant PIK3CA and Is a Vulnerability in Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2023;83:1280-1298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | He K, Guo X, Liu Y, Li J, Hu Y, Wang D, Song J. TUFM downregulation induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and invasion in lung cancer cells via a mechanism involving AMPK-GSK3β signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:2105-2121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wang Z, Li J, Long X, Jiao L, Zhou M, Wu K. MRPS16 facilitates tumor progression via the PI3K/AKT/Snail signaling axis. J Cancer. 2020;11:2032-2043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Yazicioglu YF, Marin E, Sandhu C, Galiani S, Raza IGA, Ali M, Kronsteiner B, Compeer EB, Attar M, Dunachie SJ, Dustin ML, Clarke AJ. Dynamic mitochondrial transcription and translation in B cells control germinal center entry and lymphomagenesis. Nat Immunol. 2023;24:991-1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Lei Y, Kansy BA, Li J, Cong L, Liu Y, Trivedi S, Wen H, Ting JP, Ouyang H, Ferris RL. EGFR-targeted mAb therapy modulates autophagy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma through NLRX1-TUFM protein complex. Oncogene. 2016;35:4698-4707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Xi HQ, Zhang KC, Li JY, Cui JX, Zhao P, Chen L. Expression and clinicopathologic significance of TUFM and p53 for the normal-adenoma-carcinoma sequence in colorectal epithelia. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15:90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Wang B, Ao J, Yu D, Rao T, Ruan Y, Yao X. Inhibition of mitochondrial translation effectively sensitizes renal cell carcinoma to chemotherapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;490:767-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Samec N, Jovcevska I, Stojan J, Zottel A, Liovic M, Myers MP, Muyldermans S, Šribar J, Križaj I, Komel R. Glioblastoma-specific anti-TUFM nanobody for in-vitro immunoimaging and cancer stem cell targeting. Oncotarget. 2018;9:17282-17299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zottel A, Jovčevska I, Šamec N, Mlakar J, Šribar J, Križaj I, Skoblar Vidmar M, Komel R. Anti-vimentin, anti-TUFM, anti-NAP1L1 and anti-DPYSL2 nanobodies display cytotoxic effect and reduce glioblastoma cell migration. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2020;12:1758835920915302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sighel D, Notarangelo M, Aibara S, Re A, Ricci G, Guida M, Soldano A, Adami V, Ambrosini C, Broso F, Rosatti EF, Longhi S, Buccarelli M, D'Alessandris QG, Giannetti S, Pacioni S, Ricci-Vitiani L, Rorbach J, Pallini R, Roulland S, Amunts A, Mancini I, Modelska A, Quattrone A. Inhibition of mitochondrial translation suppresses glioblastoma stem cell growth. Cell Rep. 2021;35:109024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Sighel D, Battistini G, Rosatti EF, Vigna J, Pavan M, Belli R, Peroni D, Alessandrini F, Longhi S, Pancher M, Rorbach J, Moro S, Quattrone A, Mancini I. Streptogramin A derivatives as mitochondrial translation inhibitors to suppress glioblastoma stem cell growth. Eur J Med Chem. 2023;246:114979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Shu Y, Hao Y, Feng J, Liu H, Li ST, Feng J, Jiang Z, Ye L, Zhou Y, Sun Y, Zhou Z, Wei H, Gao P, Zhang H, Sun L. Non-canonical phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase activity promotes liver cancer growth via mitochondrial translation and respiratory metabolism. EMBO J. 2022;41:e111550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 42. | Xu D, Wang Y, Wu J, Zhang Z, Chen J, Xie M, Tang R, Cheng C, Chen L, Lin S, Luo X, Zheng J. MTIF2 impairs 5 fluorouracil-mediated immunogenic cell death in hepatocellular carcinoma in vivo: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic significance. Pharmacol Res. 2021;163:105265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Khan FA, Dalia Fouad, Ataya FS, Saeed U, Ji XY, Dong J. Elevated MRPS23 expression facilitates aggressive phenotypes in breast cancer cells. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2025;70:65-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Revathi Paramasivam O, Gopisetty G, Subramani J, Thangarajan R. Expression and affinity purification of recombinant mammalian mitochondrial ribosomal small subunit (MRPS) proteins and protein-protein interaction analysis indicate putative role in tumourigenic cellular processes. J Biochem. 2021;169:675-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Lin X, Guo L, Lin X, Wang Y, Zhang G. Expression and prognosis analysis of mitochondrial ribosomal protein family in breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2022;12:10658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Liu L, Luo C, Luo Y, Chen L, Liu Y, Wang Y, Han J, Zhang Y, Wei N, Xie Z, Wu W, Wu G, Feng Y. MRPL33 and its splicing regulator hnRNPK are required for mitochondria function and implicated in tumor progression. Oncogene. 2018;37:86-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Chaudhary S, Ganguly S, Singh A, Palanichamy JK, Bakhshi R, Chopra A, Bakhshi S. Mitochondrial biogenesis gene POLG correlates with outcome in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2022;63:1005-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Chaudhary S, Ganguly S, Palanichamy JK, Singh A, Bakhshi R, Jain A, Chopra A, Bakhshi S. PGC1A driven enhanced mitochondrial DNA copy number predicts outcome in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Mitochondrion. 2021;58:246-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Liu D, Liu M, Wang W, Pang L, Wang Z, Yuan C, Liu K. Overexpression of apoptosis-inducing factor mitochondrion-associated 1 (AIFM1) induces apoptosis by promoting the transcription of caspase3 and DRAM in hepatoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;498:453-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Norberg E, Lako A, Chen PH, Stanley IA, Zhou F, Ficarro SB, Chapuy B, Chen L, Rodig S, Shin D, Choi DW, Lee S, Shipp MA, Marto JA, Danial NN. Differential contribution of the mitochondrial translation pathway to the survival of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma subsets. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:251-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Selheim F, Aasebø E, Bruserud Ø, Hernandez-Valladares M. High Mitochondrial Protein Expression as a Potential Predictor of Relapse Risk in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients with the Monocytic FAB Subtypes M4 and M5. Cancers (Basel). 2023;16:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Sharon D, Cathelin S, Mirali S, Di Trani JM, Yanofsky DJ, Keon KA, Rubinstein JL, Schimmer AD, Ketela T, Chan SM. Inhibition of mitochondrial translation overcomes venetoclax resistance in AML through activation of the integrated stress response. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11:eaax2863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 27.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Chen J, Xu X, Fan M. Inhibition of mitochondrial translation selectively targets osteosarcoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;515:9-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Heerma van Voss MR, Vesuna F, Bol GM, Afzal J, Tantravedi S, Bergman Y, Kammers K, Lehar M, Malek R, Ballew M, Ter Hoeve N, Abou D, Thorek D, Berlinicke C, Yazdankhah M, Sinha D, Le A, Abrahams R, Tran PT, van Diest PJ, Raman V. Targeting mitochondrial translation by inhibiting DDX3: a novel radiosensitization strategy for cancer treatment. Oncogene. 2018;37:63-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Fuentes-Retamal S, Sandoval-Acuña C, Peredo-Silva L, Guzmán-Rivera D, Pavani M, Torrealba N, Truksa J, Castro-Castillo V, Catalán M, Kemmerling U, Urra FA, Ferreira J. Complex Mitochondrial Dysfunction Induced by TPP(+)-Gentisic Acid and Mitochondrial Translation Inhibition by Doxycycline Evokes Synergistic Lethality in Breast Cancer Cells. Cells. 2020;9:407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Wang B, Ao J, Li X, Yu W, Yu D, Qiu C. Doxycycline sensitizes renal cell carcinoma to chemotherapy by preferentially inhibiting mitochondrial translation. J Int Med Res. 2021;49:3000605211044368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Hsu WJ, Chiang MC, Chao YC, Chang YC, Hsu MC, Chung CH, Tsai IL, Chu CY, Wu HC, Yang CC, Lee CC, Lin CW. Arginine Methylation of DDX3 by PRMT1 Mediates Mitochondrial Homeostasis to Promote Breast Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2024;84:3023-3043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Hu B, Guo Y. Inhibition of mitochondrial translation as a therapeutic strategy for human ovarian cancer to overcome chemoresistance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;509:373-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Li X, Wang M, Denk T, Buschauer R, Li Y, Beckmann R, Cheng J. Structural basis for differential inhibition of eukaryotic ribosomes by tigecycline. Nat Commun. 2024;15:5481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Herzig S, Shaw RJ. AMPK: guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19:121-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1378] [Cited by in RCA: 3067] [Article Influence: 340.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |