Published online Jan 24, 2026. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v17.i1.112801

Revised: September 3, 2025

Accepted: November 17, 2025

Published online: January 24, 2026

Processing time: 167 Days and 14.4 Hours

Lymphoproliferative neoplasms (LPNs) such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphomas are clinically heterogeneous and frequently asso

To assess the prognostic value of PD-L1/PD-1 co-expression with CXCR3, SII, SIRI, and CXCR3 expression on monocyte subsets and lymphocytes in Egyptian patients with LPNs.

A case-control study was conducted at Kafr Elsheikh University Hospitals (Janu

Patients with LPNs had marked hematological and biochemical alterations, including anemia, thrombocytopenia, and reduced neutrophils, with significantly elevated lactate dehydrogenase, C-reactive protein, ferritin, and systemic inflammatory indices (SII, SIRI). Inflammatory ratios (neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio) were lower, whereas the ferritin-to-lymphocyte ratio was higher compared with controls. Immune profiling showed significantly increased PD-L1/CXCR3 and PD-1/CXCR3 co-expression and higher CXCR3 expression on T lymphocytes. Post-treatment, PD-L1/CXCR3, CXCR3/T lymphocyte expression, SII, and SIRI decreased. Prognostic evaluation revealed that SIRI, PD-L1/CXCR3, and PD-1/CXCR3 had high accuracy for identifying stage IV disease, with patients showing low baseline levels achieving superior survival (100% follow-up). Clinically, 21.1% achieved complete remission, 26.7% relapsed, and 15.6% died.

PD-L1/PD-1 co-expression with CXCR3, combined with SII and SIRI, constitutes a practical prognostic panel for staging and outcome prediction in Egyptian patients with LPNs. These biomarkers may guide personalized management and therapeutic monitoring.

Core Tip: This case-control study explores the prognostic value of programmed death-ligand 1/programmed cell death protein 1 co-expression and C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3)-driven immune signatures in Egyptian patients with lymphoproliferative neoplasms. By integrating flow cytometry analysis with systemic inflammation indices (systemic immune-inflammation index and systemic inflammation response index), the study identifies novel biomarker panels predictive of disease stage, recurrence, and survival. Findings support the use of programmed death-ligand 1/CXCR3 and programmed cell death protein 1/CXCR3 as clinically relevant tools for risk stratification in resource-limited settings, paving the way for the personalized management of lymphoproliferative neoplasms.

- Citation: Sherief DE, Nosair N, Abdelhameed AM, Sadaka E, Othman AAA, Elgamal R. Prognostic significance of PD-L1/PD-1 co-expression and CXCR3-driven inflammatory signatures in Egyptian patients with lymphoproliferative neoplasms. World J Clin Oncol 2026; 17(1): 112801

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v17/i1/112801.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v17.i1.112801

Lymphoproliferative neoplasms (LPNs), including non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), are a group of hematological malignancies arising from the lymphatic and reticuloendothelial systems. Globally, NHL ac

Despite advancements in chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, the clinical course of LPNs remains unpredictable. Disease progression and immune evasion mechanisms, particularly in relapsed or refractory cases, underscore the need for reliable prognostic biomarkers[4]. Among potential targets, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor (CXCR) 3 and immune checkpoint molecules programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and pro

CXCR3 is a G protein-coupled receptor expressed on cluster of differentiation 4-positive (CD4+) and CD8+ T cells, regulatory T cells, and certain monocyte subsets. It binds interferon gamma (IFN-γ)-inducible chemokines (CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11), orchestrating T helper 1 cell-mediated immune responses and exerting antiangiogenic effects[5,6]. However, paradoxically, overexpression of CXCR3 in lymphomas may support tumor cell survival, proliferation, and metastasis through ligand-mediated signaling[6]. Similarly, the PD-1/PD-L1 axis plays a pivotal role in suppressing cytotoxic T-cell function, thereby facilitating immune evasion in hematological malignancies and serving as a target for checkpoint blockade therapy[7].

In addition to molecular markers, systemic inflammation is increasingly recognized as a key determinant of cancer progression. Inflammatory indices such as the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) and systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) have been associated with tumor burden, metastasis, and survival in several malignancies[8,9]. These markers are inexpensive, reproducible, and easily derived from routine blood tests, making them attractive candidates for risk stratification. However, their prognostic integration with immune checkpoint signatures, particularly in lymphoid malignancies, remains poorly studied.

In the Egyptian context, data on these emerging immuno-inflammatory markers in LPNs are sparse. Most available studies have focused on epidemiology or treatment outcomes without evaluating the prognostic role of immune checkpoint co-expression or monocyte subset phenotyping[10]. Therefore, this study evaluated the prognostic value of PD-L1/PD-1 co-expression with CXCR3, alongside SII and SIRI, in Egyptian patients with LPNs.

This case-control study was conducted to evaluate immunoinflammatory prognostic biomarkers in Egyptian patients with LPNs. The study was conducted over a 12-month period from January 2024 to January 2025 at the Clinical Pathology, Internal Medicine, and Departments of Oncology of Kafr Elsheikh University Hospitals (Kafr Elsheikh, Egypt), with additional recruitment and collaboration from the Department of Internal Medicine and Department of Clinical Pathology of Suez University Hospital (Ismaileya, Egypt). A total of 90 adult patients with newly diagnosed LPNs and 90 healthy age- and sex-matched controls were enrolled. Eligible patients were diagnosed with one of four histopathological confirmed subtypes: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), follicular lymphoma (FL), or mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). The protocol initially proposed a smaller sample size (60 patients and 60 controls); however, the expansion to 90 patients and 90 controls was pre-specified during the protocol stage, before data collection and analysis, to improve statistical power and enable more robust subgroup analyses.

Sample size adequacy was confirmed using G*Power software version 3.1 (Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany). The final sample of 90 patients and 90 matched controls was calculated to achieve a statistical power of 80% to detect a moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.5) for between-group comparisons, with a two-sided α of 0.05. This sample also enabled sufficient power for subgroup (CLL, DLBCL, FL, MCL) and survival analyses (minimum 10 outcome events per predictor variable). The study design and reporting adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines for case-control studies to ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility.

This study received approval from the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of Kafr Elsheikh University (Approval No. KFSIRB200-232). All procedures were conducted in compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants after a full explanation of the study objectives, procedures, potential benefits, and risks. Participants were assured of confidentiality, and data were anonymized during analysis and reporting.

Patients were eligible if they were aged 18 years or older and had a newly diagnosed, histologically and immunophenotypically confirmed LPN subtype (CLL, DLBCL, FL, or MCL). Diagnostic confirmation was based on lymph node biopsy, bone marrow aspiration, and flow cytometry immunophenotyping in all patients. Only patients with complete baseline clinical, pathological, and laboratory data were included to ensure consistency in comparative analyses.

Patients were excluded if they had a personal history of any other hematological malignancy or solid tumor, as the presence of concurrent neoplastic diseases could confound biomarker interpretation. Individuals with chronic inflammatory or autoimmune disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus or rheumatoid arthritis, were excluded to avoid elevation of inflammatory indices unrelated to malignancy. Patients with recent major surgery, active infections (including upper respiratory tract infections), or trauma within the past 4 weeks were also excluded, given the potential for transient elevations in systemic inflammation markers. Chronic viral infections such as human immunodeficiency virus, active hepatitis B, or hepatitis C were exclusionary due to their known effects on immune checkpoints and cytokine expression, which could bias PD-L1/PD-1 and CXCR3 profiling. Lastly, any case lacking full diagnostic, laboratory, or follow-up data was excluded to maintain methodological integrity and ensure reliability of statistical comparisons. Healthy controls were selected from blood donors and medical personnel, confirmed to be free from systemic illness and malignancy, with normal body mass index and laboratory findings.

The primary outcomes were immunological and inflammatory markers of prognostic significance. These included PD-L1 and PD-1 co-expression with CXCR3 on CD3+ T lymphocytes, CXCR3 expression on CD14/CD16-defined monocyte subsets (classical, intermediate, non-classical), and composite inflammatory indices, namely, the SII and the SIRI. These biomarkers were assessed for their associations with disease severity and treatment response.

Secondary outcomes included clinical stage, classified by the Ann Arbor staging system; therapeutic response (categorized into complete remission, partial remission, refractory disease, and recurrence); and survival outcomes, including overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (EFS) assessed during follow-up.

Clinical evaluation: All patients underwent standardized clinical evaluations, which included a thorough history with documentation of age, sex, body mass index, B-symptoms, presence of lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly, followed by a comprehensive physical examination. Disease staging was performed according to the Ann Arbor classification system, integrating clinical findings with radiological imaging.

Selection of markers: All immunophenotypic and inflammatory markers were selected a priori based on their biological relevance and prior evidence in hematologic malignancies.

Hematological and biochemical investigations: For laboratory assessment, fasting venous blood samples were obtained between 8:00 and 10:00 following an overnight fast. A 2.5 mL aliquot of whole blood was collected into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes and immediately analyzed using the Sysmex XN-550 cell counter Sysmex Corporation, (Kobe, Japan) to determine hematological parameters, including hemoglobin concentration, platelet count, total leukocyte count, and differential leukocyte counts, for calculation of inflammatory ratios [neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), white cell-to-lymphocyte ratio, and ferritin-to-lymphocyte ratio).

An additional 3 mL of blood was drawn into plain tubes, allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 minutes, and centrifuged at 1500 g for 10 minutes to obtain serum. Serum aliquots were used to measure C-reactive protein (CRP) by immunoturbidimetric assay, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) by the enzyme kinetic method, and ferritin by chemiluminescent immunoassay on the Cobas e411 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, United States). Renal (urea, creatinine) and liver (alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, bilirubin, albumin) function tests, as well as random blood glucose, were performed on the same serum samples using the Architect c8000 analyzer (Abbott Lab

Flow cytometry: For flow cytometry analyses, an additional 4 mL of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-anticoagulated blood was processed within 4 hours of collection. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation, washed, and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies against CD3, CD14, CD16, PD-1, PD-L1, and CXCR3. Data acquisition was conducted on the BD FACSCalibur instrument (BD Biosciences, Milpitas, CA, United States), and analyses were performed using FlowJo version 10 software.

Monocyte subsets were defined as classical (CD14++CD16-), intermediate (CD14++CD16+), and non-classical (CD14+CD16++), and CXCR3 expression was quantified on each subset as well as on gated CD3+ T lymphocytes. Flow cytometry data acquisition and analysis were conducted by laboratory personnel blinded to the case or control status to minimize measurement bias.

The following fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies were used: CD3 (clone UCHT1, PerCP; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, United States), CD14 (clone M5E2, PE; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, United States), CD16 (clone 3G8, FITC; BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, United States), PD-1 (clone EH12.2H7, APC; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, United States), PD-L1 (clone 29E.2A3, FITC; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, United States), and CXCR3 (clone G025H7, PE; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, United States).

Data analysis was performed using a standardized sequential gating strategy. Initially, singlet events were selected by plotting forward scatter (FSC) area vs height to exclude doublets. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were gated on FSC and side scatter (SSC) properties to exclude debris. Within this gate, lymphocytes were identified as small FSC/SSC events and further gated on CD3+ T lymphocytes, followed by assessment of PD-1, PD-L1, and CXCR3 expression. Monocytes were identified as larger FSC/SSC events and gated as CD14+ cells. Subsets were then defined as classical (CD14++CD16-), intermediate (CD14++CD16+), and non-classical (CD14+CD16++), as recommended by the International Union of Immunological Societies and recent consensus guidelines[7]. CXCR3 expression was quantified within each monocyte subset. Fluorescence compensation was applied using single-stained controls, and isotype controls were used to verify specificity.

Radiological investigations: Radiological investigations included chest radiography, abdominal ultrasonography, and either contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT for accurate disease staging and assessment of extranodal involvement. Bone marrow aspiration was systematically performed in all patients as part of standard lymphoma staging protocols, regardless of subtype or disease stage, in line with institutional hematological guidelines.

OS was defined as the time from diagnosis until death from any cause or last follow-up. EFS was defined as the time from diagnosis to the first occurrence of progression, relapse, initiation of new therapy, or death, whichever came first. Clinical response was evaluated according to standard international criteria, with complete remission defined as the dis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous variables were assessed for normality and summarized as means ± SD or medians (interquartile range), as appropriate. Group comparisons between patients and controls were performed using independent t-tests for normally distributed variables or the Mann-Whitney U test for skewed distributions. Categorical data were presented as fre

Comparative analyses among LPN subtypes or Ann Arbor stages were conducted using the Kruskal-Wallis test with post hoc pairwise comparisons. Diagnostic performance of biomarkers was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, and optimal cutoff values were derived using the Youden index. The area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, and specificity were calculated for each parameter. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to estimate OS and EFS, and log-rank tests assessed significance between subgroups. Two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A post hoc power analysis was conducted using G*Power software version 3.1 (Heinrich Heine University) to confirm that the final sample size provided at least 80% power to detect moderate effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 0.5) at a significance level of α = 0.05.

Missing data were assessed for all variables. Cases with incomplete or missing values for primary biomarkers or clinical outcomes were excluded from relevant subgroup or survival analyses. No statistical imputation was performed. A complete case analysis was adopted to maintain data integrity and minimize bias.

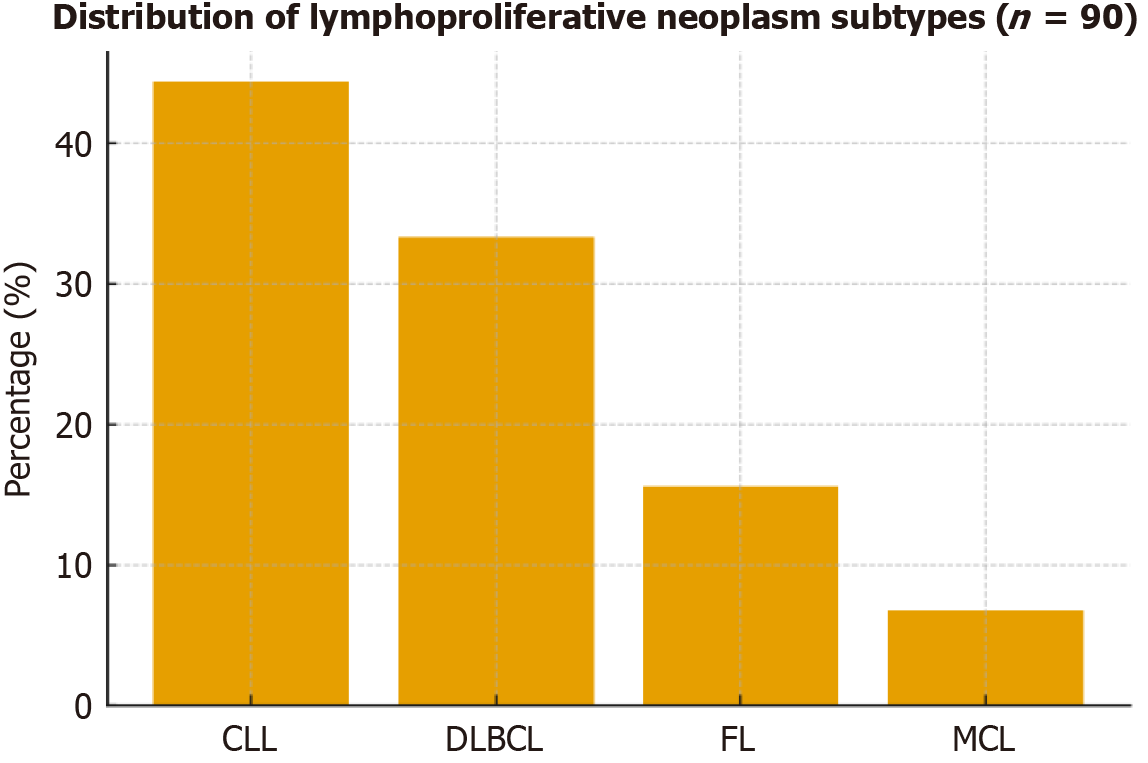

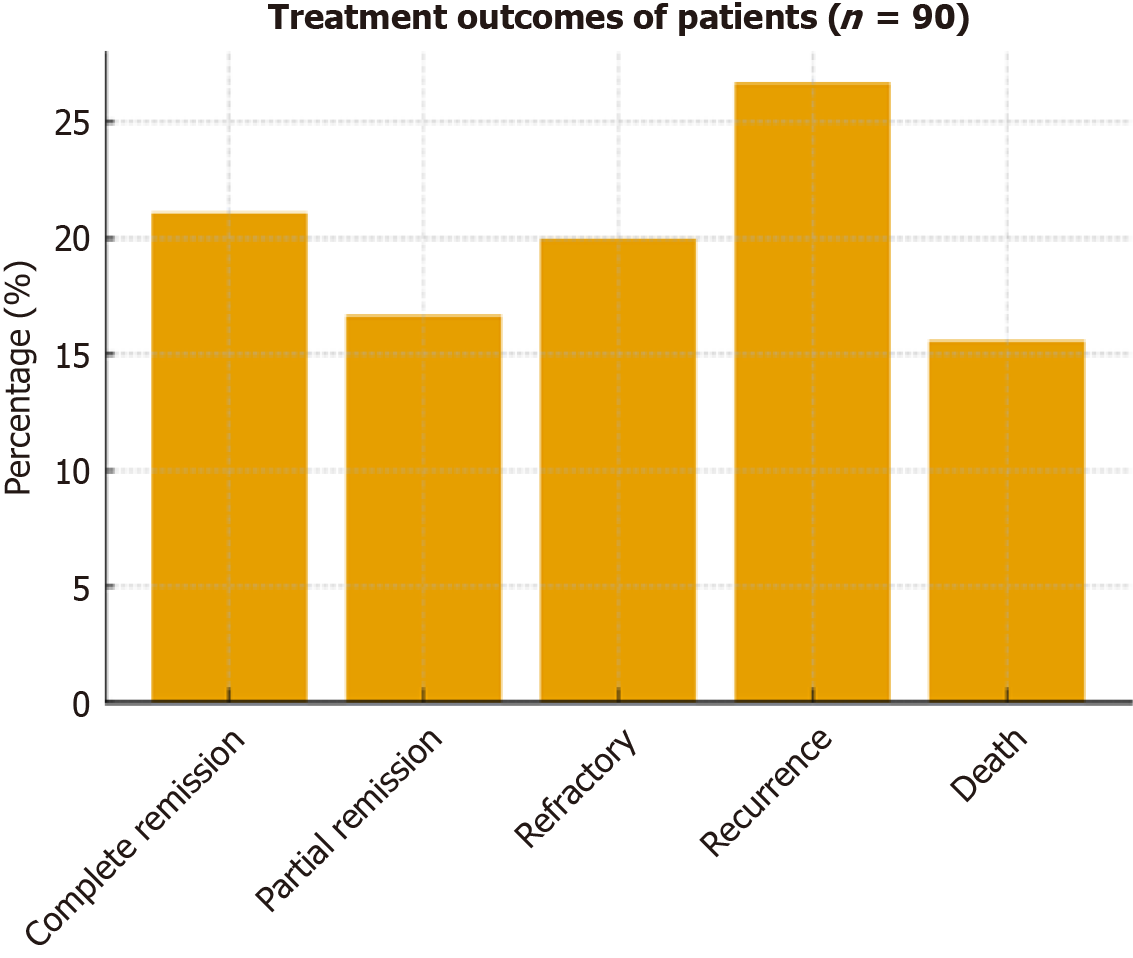

The study included 90 patients with LPNs (mean age 59.17 ± 7.72 years; 37.8% male) and 90 age- and sex-matched healthy controls (mean age 58.19 ± 7.72 years; 46.7% male). As groups were matched for age and sex, these variables are presented descriptively without statistical comparison (Table 1). Among patients, CLL was the most prevalent diagnosis (44.4%), followed by DLBCL (33.3%), FL (15.6%), and MCL (6.7%; Figure 1). Clinical examination revealed lymph node involvement in 58.9%, bone marrow involvement in 35.6%, hepatomegaly in 13.3%, and splenomegaly in 7.8%. Most patients presented with advanced disease (stage IV: 42.2%; stage III: 7.8%), followed by stage II (28.9%) and stage I (21.1%) according to the Ann Arbor classification (Table 2). Treatment outcomes included complete remission (21.1%), partial remission (16.7%), refractory response (20.0%), recurrence (26.7%), and death (15.6%; Figure 2).

| Variable | Patients (n = 90) | Controls (n = 90) |

| Age (years) | 59.17 ± 7.72 | 58.19 ± 7.72 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 34 (37.8) | 42 (46.7) |

| Female | 56 (62.2) | 48 (53.3) |

| Variable | |

| Lymph node involvement | 53 (58.9) |

| Bone marrow involvement | 32 (35.6) |

| Hepatomegaly | 12 (13.3) |

| Splenomegaly | 7 (7.8) |

| Ann Arbor stage | |

| Stage I | 19 (21.1) |

| Stage II | 26 (28.9) |

| Stage III | 7 (7.8) |

| Stage IV | 38 (42.2) |

Patients with LPNs exhibited significant alterations compared to controls (Table 3). Hemoglobin, platelet count, neutrophil count, eosinophil count, transferrin saturation, and albumin were significantly lower, while lymphocyte count, LDH, CRP, ferritin, beta-2 microglobulin (B2M), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were significantly higher. Total leukocyte and monocyte counts showed no significant differences.

| Parameter | Patients (n = 90) | Controls (n = 90) | P value |

| Hematological parameters | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.31 ± 1.03 | 13.41 ± 0.77 | < 0.001c |

| Platelet count (× 109/L) | 95.4 ± 9.87 | 258.3 ± 60.98 | < 0.001c |

| Total leukocyte count (× 109/L) | 20.74 ± 21.78 | 7.43 ± 1.81 | 0.209 |

| Neutrophil count (× 109/L) | 3.1 ± 2.79 | 4.16 ± 1.05 | 0.005b |

| Lymphocyte count (× 109/L) | 15.99 ± 17.73 | 2.36 ± 0.73 | 0.010a |

| Monocyte count (× 109/L) | 0.591 ± 0.233 | 0.500 ± 0.150 | 0.774 |

| Eosinophil count (× 109/L) | 0.244 ± 0.259 | 0.268 ± 0.165 | 0.008b |

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| LDH (U/L) | 615.9 ± 69.72 | 121.6 ± 18.05 | < 0.001c |

| CRP (mg/L) | 28.2 ± 12.22 | 3.43 ± 1.61 | < 0.001c |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 540 ± 84.64 | 82.2 ± 40.81 | < 0.001c |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | 36.87 ± 7.3 | 64.67 ± 16.13 | < 0.001c |

| Beta-2 microglobulin (mg/L) | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | < 0.001c |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | < 0.001c |

| ESR (mm/hour) | 45.0 ± 15.0 | 12.0 ± 4.0 | < 0.001c |

| Inflammatory indices | |||

| SII | 30971.8 ± 14428.6 | 455.0 ± 211.9 | < 0.001c |

| SIRI | 250.7 ± 200.2 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | < 0.001c |

| Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio | 29.6 ± 23.97 | 115.0 ± 38.33 | < 0.001c |

| Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio | 0.32 ± 0.14 | 1.68 ± 0.58 | < 0.001c |

| Ferritin-to-lymphocyte ratio | 0.18 ± 0.17 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.016a |

| White cell-to-lymphocyte ratio | 1.44 ± 0.15 | 3.25 ± 0.62 | < 0.001c |

| LDH-to-lymphocyte ratio | 26.37 ± 27.93 | 21.14 ± 9.28 | 0.133 |

Inflammatory indices were also markedly altered in patients (Table 3). SII, SIRI, and ferritin-to-lymphocyte ratio were significantly elevated, whereas PLR, NLR, and white cell-to-lymphocyte ratio were significantly lower compared with controls. No significant difference was observed for LLR.

Patients with LPNs showed significant alterations in checkpoint and chemokine receptor expression compared to controls (Table 4). Co-expression of PD-L1/CXCR3 and PD-1/CXCR3, as well as CXCR3 expression on T lymphocytes, intermediate monocytes, and non-classical monocytes, was significantly higher in patients, whereas CXCR3 expression on classical monocytes was reduced. Both SII and SIRI were markedly elevated in patients relative to controls. Following treatment (n = 76, excluding 14 deaths), PD-L1/CXCR3, CXCR3/T lymphocyte expression, SII, and SIRI were significantly decreased, whereas PD-1/CXCR3 and CXCR3 expression on monocyte subsets showed no significant changes (Table 5).

| Parameter | Patients (n = 90) | Controls (n = 90) | P value |

| SII | 30971.8 ± 14428.6 | 455.0 ± 211.9 | < 0.001b |

| SIRI | 250.7 ± 200.2 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | < 0.001b |

| PD-L1/CXCR3 (%) | 51.1 ± 16.77 | 2.51 ± 0.31 | < 0.001b |

| PD-1/CXCR3 (%) | 12.28 ± 1.46 | 1.48 ± 0.31 | < 0.001b |

| CXCR3/T lymphocytes (%) | 52.03 ± 9.4 | 12.34 ± 1.3 | < 0.001b |

| CXCR3/classical monocytes (%) | 14.57 ± 5.78 | 43.23 ± 7.9 | < 0.001b |

| CXCR3/intermediate monocytes (%) | 20.56 ± 7.31 | 4.48 ± 1.66 | < 0.001b |

| CXCR3/non-classical monocytes (%) | 15.0 ± 7.20 | 12.69 ± 1.63 | 0.039a |

| Parameter | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | P value |

| SII | 30971.8 ± 14428.6 | 1500.0 ± 800.0 | < 0.001b |

| SIRI | 250.7 ± 200.2 | 5.0 ± 2.5 | < 0.001b |

| PD-L1/CXCR3 (%) | 51.10 ± 16.77 | 43.31 ± 24.45 | 0.011a |

| PD-1/CXCR3 (%) | 12.28 ± 1.46 | 12.75 ± 7.57 | 0.366 |

| CXCR3/T lymphocytes (%) | 52.03 ± 9.40 | 12.75 ± 7.57 | < 0.001b |

| CXCR3/classical monocytes (%) | 14.57 ± 5.78 | 13.50 ± 5.50 | 0.052 |

| CXCR3/intermediate monocytes (%) | 20.56 ± 7.31 | 19.00 ± 6.50 | 0.068 |

| CXCR3/non-classical monocytes (%) | 15.0 ± 7.20 | 14.00 ± 6.00 | 0.075 |

SII and SIRI significantly differed across lymphoma subtypes, with the highest SII in DLBCL and the highest SIRI in CLL (Table 6). PD-L1/CXCR3 and PD-1/CXCR3 expression did not significantly vary across subtypes, whereas CXCR3 expression on monocyte subsets was highest in CLL.

| Parameter | CLL (n = 40) | DLBCL (n = 30) | Follicular (n = 14) | Mantle cell (n = 6) | P value |

| SII | 19654.6 ± 9090.0 | 40893.3 ± 10472.1 | 38427.1 ± 11682.8 | 39416.7 ± 14621.4 | < 0.001a |

| SIRI | 447.3 ± 130.5 | 87.09 ± 41.71 | 105.2 ± 56.61 | 96.77 ± 65.02 | < 0.001a |

| PD-L1/CXCR3 (%) | 50.71 ± 17.77 | 51.51 ± 15.98 | 49.87 ± 17.47 | 54.50 ± 15.86 | 0.745 |

| PD-1/CXCR3 (%) | 12.14 ± 1.60 | 12.48 ± 1.29 | 12.10 ± 1.43 | 12.67 ± 1.51 | 0.638 |

| CXCR3/T lymphocytes (%) | 52.65 ± 9.76 | 48.37 ± 8.84 | 54.69 ± 8.60 | 60.0 ± 1.79 | 0.383 |

| CXCR3/classical monocytes (%) | 19.95 ± 2.94 | 11.0 ± 2.86 | 9.14 ± 3.57 | 9.17 ± 4.49 | < 0.001a |

| CXCR3/intermediate monocytes (%) | 26.58 ± 4.93 | 17.60 ± 4.81 | 12.86 ± 3.82 | 13.17 ± 4.07 | < 0.001a |

| CXCR3/non-classical monocytes (%) | 20.80 ± 4.43 | 13.23 ± 5.16 | 5.71 ± 1.27 | 6.83 ± 1.17 | < 0.001a |

Across disease stages, SII increased progressively with advancing stage, while SIRI was highest in early stages (I-II) and declined in stage IV. PD-L1/CXCR3 and PD-1/CXCR3 expression rose in stage IV, whereas CXCR3 expression on all monocyte subsets decreased with advancing stage (Table 7).

| Parameter | Stage I (n = 19) | Stage II (n = 26) | Stage III (n = 7) | Stage IV (n = 38) | P value |

| SII | 22678.1 ± 13309.1 | 25768.0 ± 4783.7 | 39278.6 ± 16261.4 | 37149.0 ± 10837.2 | < 0.001b |

| SIRI | 443.6 ± 178.1 | 373.6 ± 151.9 | 210.2 ± 142.2 | 77.52 ± 35.26 | < 0.001b |

| PD-L1/CXCR3 (%) | 51.77 ± 18.69 | 45.62 ± 17.57 | 35.71 ± 3.45 | 57.35 ± 13.79 | 0.002a |

| PD-1/CXCR3 (%) | 12.10 ± 1.71 | 11.80 ± 1.60 | 11.10 ± 0.22 | 12.92 ± 1.06 | 0.002a |

| CXCR3/T lymphocytes (%) | 51.02 ± 9.99 | 50.72 ± 9.77 | 53.29 ± 8.62 | 53.21 ± 9.16 | 0.089 |

| CXCR3/classical monocytes (%) | 18.58 ± 4.02 | 18.0 ± 5.90 | 12.29 ± 5.19 | 10.63 ± 3.33 | < 0.001b |

| CXCR3/intermediate monocytes (%) | 26.53 ± 5.45 | 24.27 ± 6.50 | 18.71 ± 5.65 | 15.37 ± 4.93 | < 0.001b |

| CXCR3/non-classical monocytes (%) | 18.84 ± 6.10 | 18.58 ± 7.03 | 10.57 ± 6.83 | 11.45 ± 5.69 | < 0.001b |

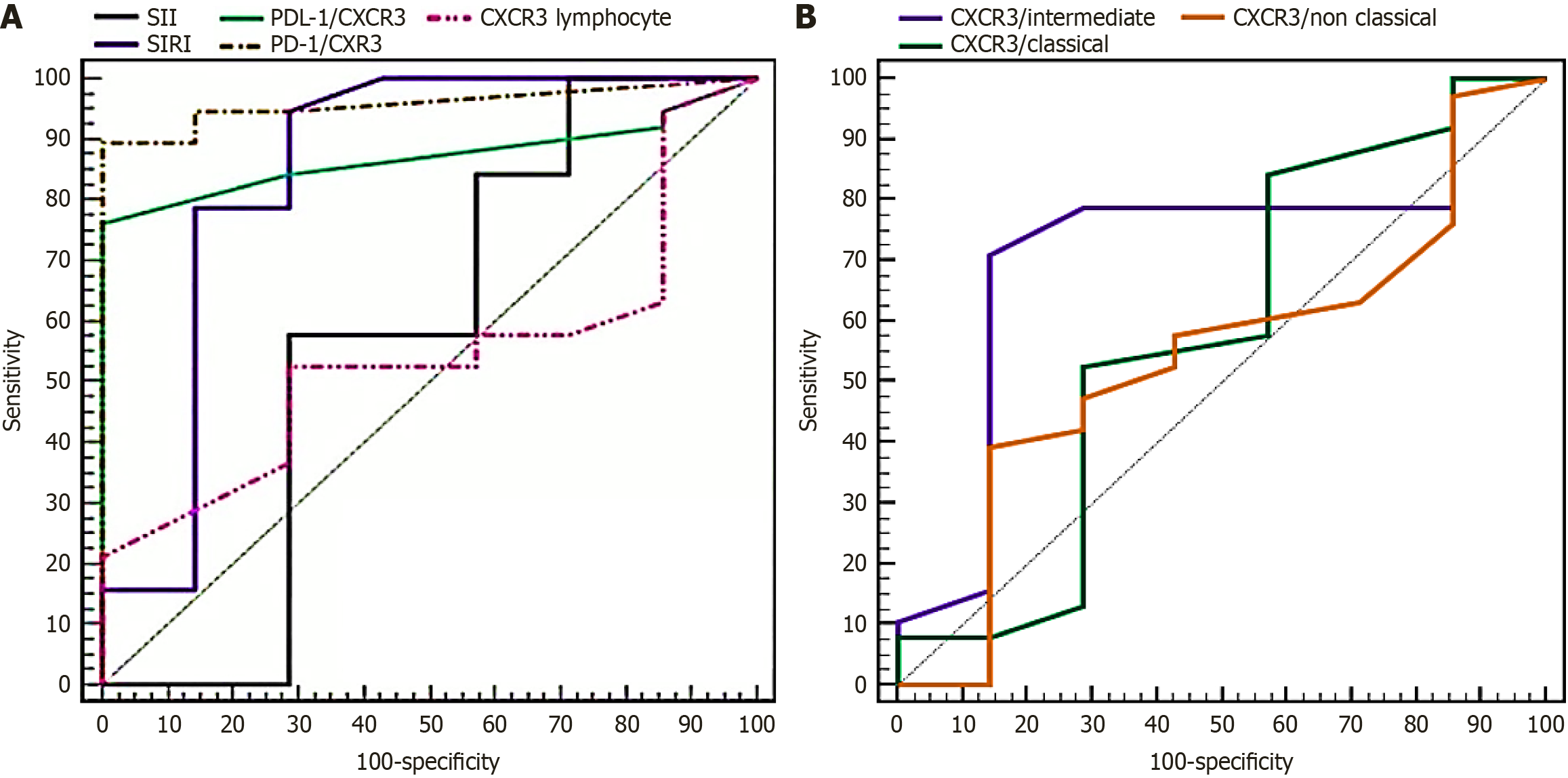

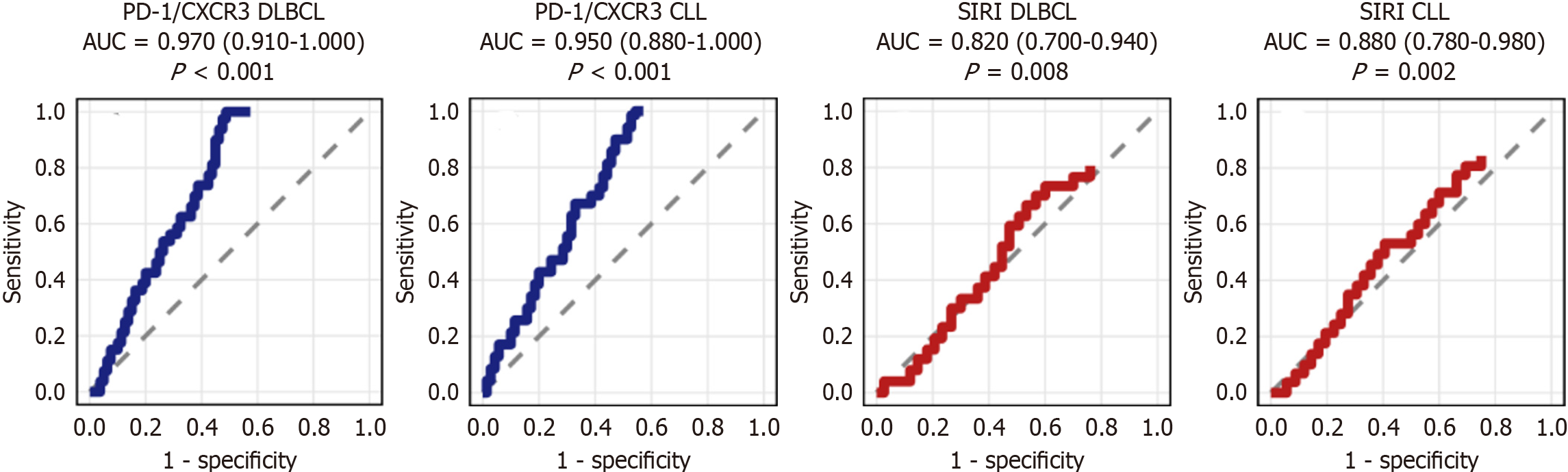

ROC analysis demonstrated that SIRI, PD-L1/CXCR3, and PD-1/CXCR3 had the highest diagnostic accuracy for distinguishing stage IV from earlier stages, with AUCs > 0.84 and sensitivities of 79%-89% (Figure 3, Table 8). CXCR3 ex

| Biomarker | AUC | 95%CI | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | P value |

| SIRI | 0.846 | 0.628-1.000 | 78.95 | 71.43 | 0.004a |

| PD-L1/CXCR3 | 0.872 | 0.771-0.973 | 84.21 | 71.43 | 0.002a |

| PD-1/CXCR3 | 0.959 | 0.903-1.000 | 89.47 | 85.71 | < 0.001b |

| CXCR3/intermediate monocytes | 0.720 | 0.508-0.932 | 78.95 | 71.43 | 0.067 |

| SII | 0.650 | 0.450-0.850 | 60.00 | 65.00 | > 0.05 |

| CXCR3/T-lymphocytes (%) | 0.600 | 0.400-0.800 | 55.00 | 60.00 | > 0.05 |

| CXCR3/classical monocytes (%) | 0.580 | 0.380-0.780 | 57.89 | 42.86 | > 0.05 |

| CXCR3/non-classical monocytes (%) | 0.590 | 0.390-0.790 | 57.89 | 57.14 | > 0.05 |

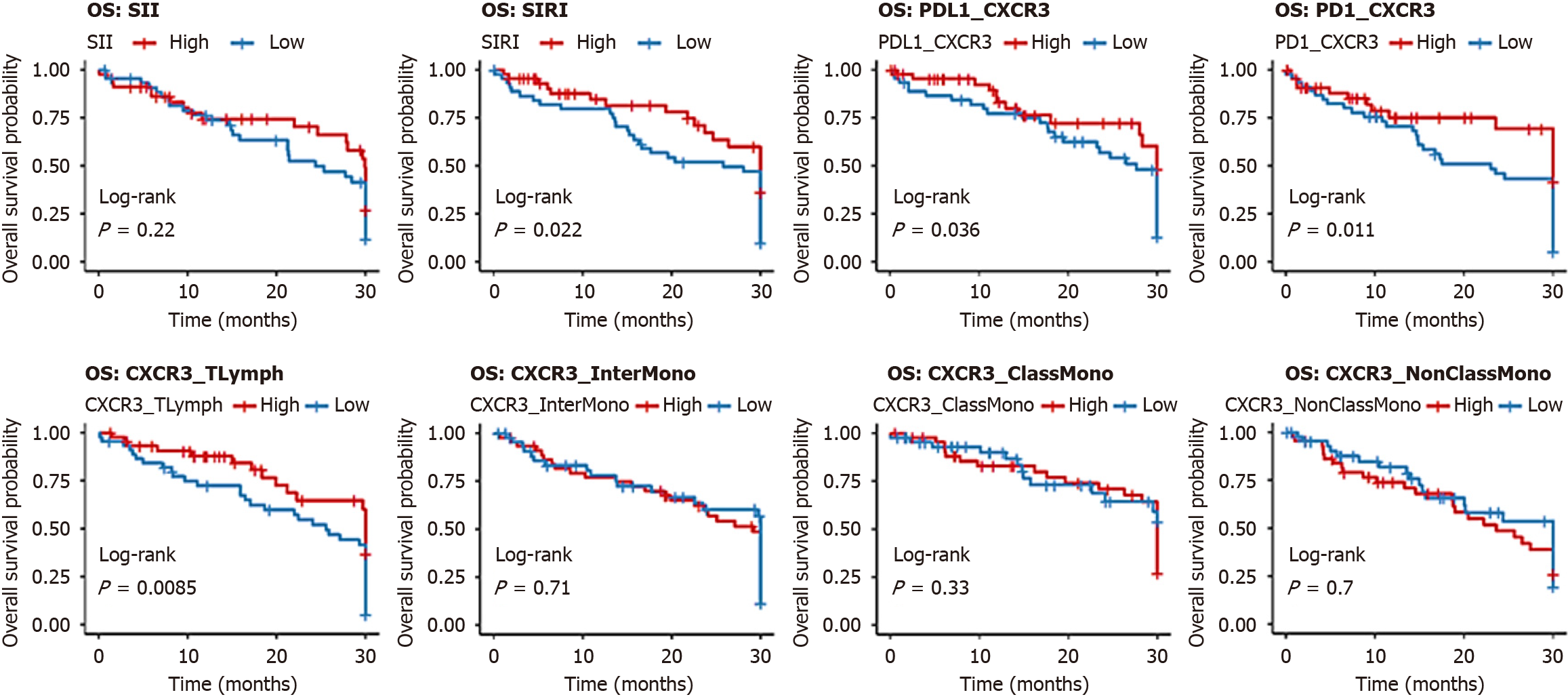

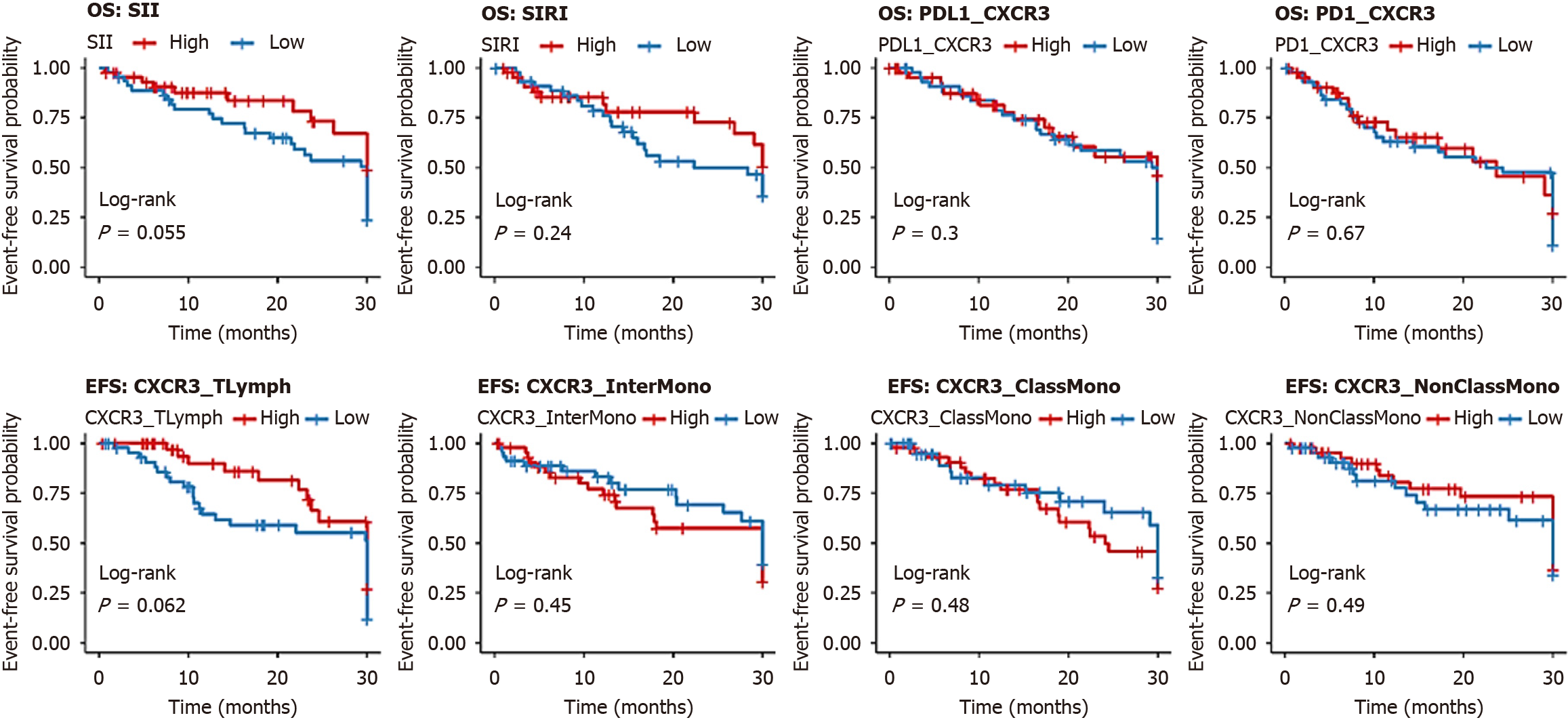

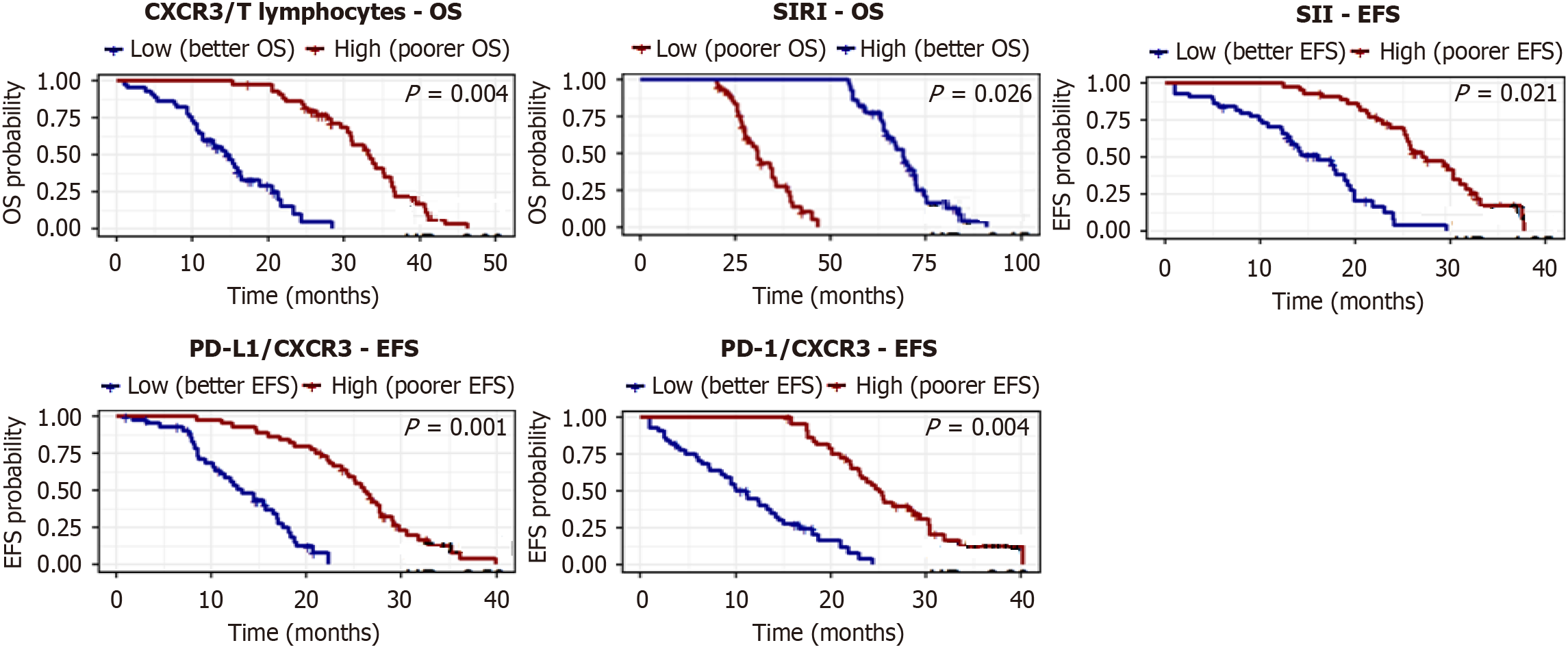

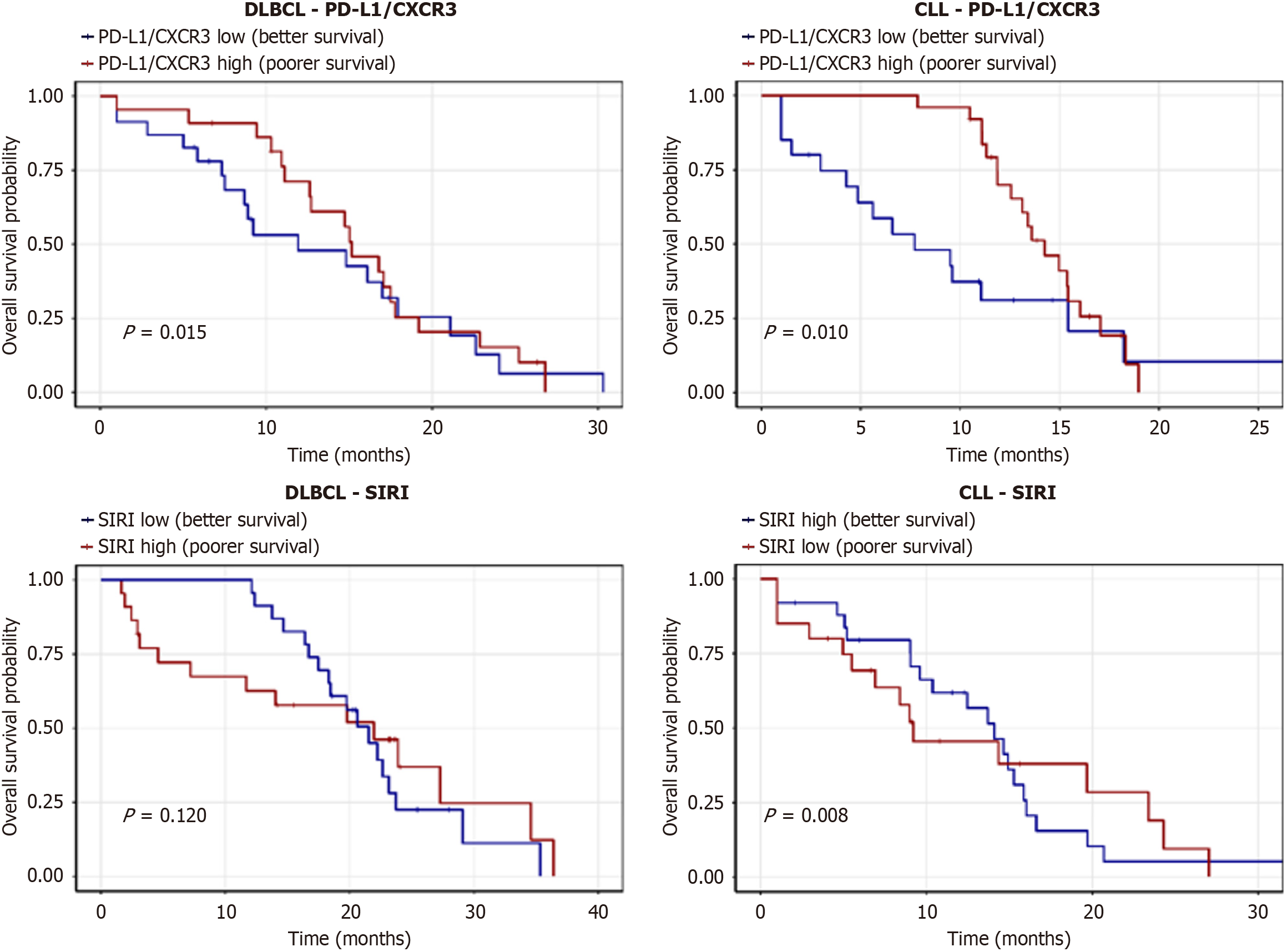

Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that low levels of SIRI, PD-L1/CXCR3, PD-1/CXCR3, and CXCR3/T lymphocytes were associated with significantly longer OS, whereas high expression of CXCR3 on intermediate and classical monocytes also correlated with favorable OS. No significant OS differences were found for SII or CXCR3/non-classical monocytes (Figure 4, Table 9). For EFS, patients with low SII, SIRI, PD-L1/CXCR3, PD-1/CXCR3, and CXCR3/T lymphocytes demonstrated significantly longer survival, while monocyte subsets showed no significant impact (Figure 5, Table 10).

| Parameter | Group (n) | Mean OS (months) | Survival at endpoint (%) | Log-rank χ2 | P value | Hazard ratio (95%CI) |

| SII | Low (45) | 25.211 ± 2.50 | 70.0 | 0.021 | 0.884 | 1.10 (0.80-1.50) |

| High (45) | 25.104 ± 2.45 | 50.0 | ||||

| SIRI | Low (45) | 29.167 ± 1.20 | 85.0 | 8.026 | 0.005b | 1.80 (1.20-2.70) |

| High (45) | 23.452 ± 2.30 | 40.0 | ||||

| PD-L1/CXCR3 | Low (45) | 29.367 ± 1.10 | 80.0 | 6.999 | 0.008b | 1.90 (1.25-2.90) |

| High (45) | 23.575 ± 2.40 | 40.0 | ||||

| PD-1/CXCR3 | Low (45) | 24.067 ± 1.50 | 80.0 | 6.381 | 0.012a | 1.70 (1.15-2.50) |

| High (45) | 23.630 ± 2.50 | 40.0 | ||||

| CXCR3/T lymphocytes (%) | Low (45) | 29.167 ± 1.20 | 80.0 | 7.239 | 0.007b | 1.85 (1.20-2.80) |

| High (45) | 23.534 ± 2.30 | 40.0 | ||||

| CXCR3/classical monocytes (%) | Low (45) | 24.026 ± 1.80 | 50.0 | 4.925 | 0.026a | 1.50 (1.00-2.25) |

| High (45) | 27.804 ± 1.50 | 75.0 | ||||

| CXCR3/intermediate monocytes (%) | Low (45) | 23.782 ± 2.00 | 40.0 | 7.281 | 0.007b | 1.60 (1.05-2.40) |

| High (45) | 28.133 ± 1.40 | 50.0 | ||||

| CXCR3/non-classical monocytes (%) | Low (45) | 24.174 ± 1.90 | 50.0 | 3.490 | 0.062 | 1.30 (0.85-2.00) |

| High (45) | 26.980 ± 1.60 | 50.0 |

| Parameter | Group (n) | Mean EFS (months) | Survival at endpoint (%) | Log-rank χ2 | P value | Hazard ratio (95%CI) |

| SII | Low (45) | 24.19 ± 1.80 | 60.0 | 8.857 | 0.003b | 1.75 (1.15-2.65) |

| High (45) | 18.65 ± 2.50 | 30.0 | ||||

| SIRI | Low (45) | 22.44 ± 2.00 | 60.0 | 4.625 | 0.032a | 1.50 (1.00-2.25) |

| High (45) | 19.06 ± 2.30 | 30.0 | ||||

| PD-L1/CXCR3 | Low (45) | 27.857 ± 1.50 | 70.0 | 15.498 | < 0.001c | 2.00 (1.30-3.00) |

| High (45) | 18.005 ± 2.00 | 30.0 | ||||

| PD-1/CXCR3 | Low (45) | 24.067 ± 1.50 | 80.0 | 23.331 | < 0.001c | 2.20 (1.40-3.40) |

| High (45) | 17.648 ± 2.20 | 30.0 | ||||

| CXCR3/T lymphocytes (%) | Low (45) | 24.354 ± 1.50 | 60.0 | 8.987 | 0.003b | 1.80 (1.20-2.70) |

| High (45) | 18.700 ± 2.00 | 30.0 | ||||

| CXCR3/classical monocytes (%) | Low (45) | 21.727 ± 1.80 | 40.0 | 1.532 | 0.216 | 1.20 (0.80-1.80) |

| High (45) | 19.462 ± 2.00 | 40.0 | ||||

| CXCR3/intermediate monocytes (%) | Low (45) | 22.525 ± 1.80 | 40.0 | 3.561 | 0.059 | 1.30 (0.85-2.00) |

| High (45) | 18.531 ± 2.00 | 40.0 | ||||

| CXCR3/non-classical monocytes (%) | Low (45) | 22.072 ± 1.90 | 40.0 | 1.874 | 0.171 | 1.20 (0.80-1.80) |

| High (45) | 19.087 ± 2.00 | 40.0 |

Spearman’s analysis revealed strong positive correlations between SII and SIRI, PD-L1/CXCR3 and PD-1/CXCR3, and between SIRI and PD-L1/CXCR3. CXCR3 expression on T lymphocytes correlated negatively with CXCR3 on classical monocytes (Table 11).

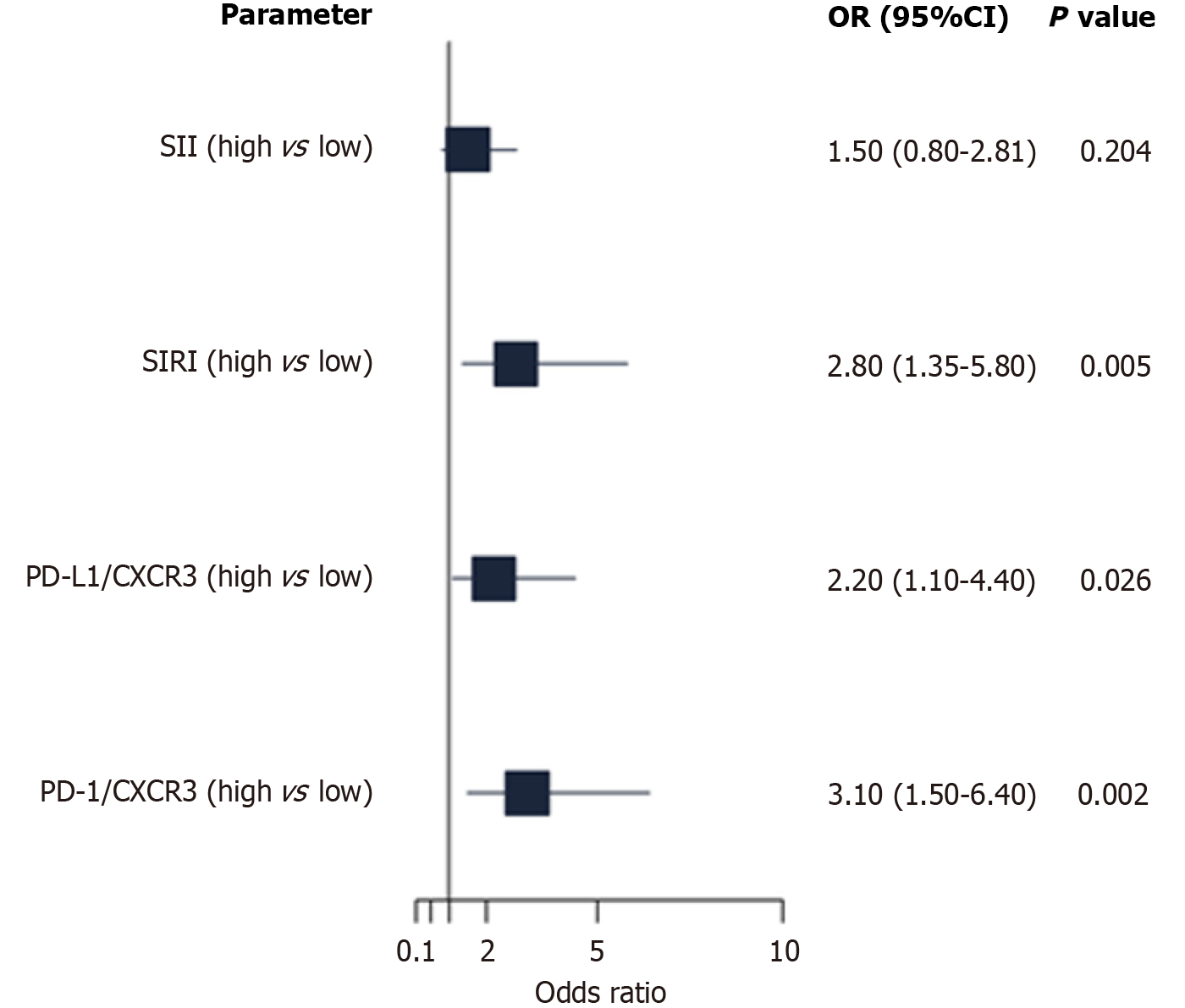

In adjusted models, high PD-L1/CXCR3, PD-1/CXCR3, and CXCR3/T lymphocyte expression independently predicted poorer OS, whereas high SIRI was associated with improved OS. For EFS, high SII, PD-L1/CXCR3, PD-1/CXCR3, and CXCR3/T lymphocytes were significant predictors of shorter survival (Figure 6, Table 12).

| Parameter | OS HR (95%CI) | OS (P value) | EFS HR (95%CI) | EFS (P value) |

| SII (high vs low) | 1.20 (0.70-2.05) | 0.510 | 1.85 (1.10-3.12) | 0.021a |

| SIRI (high vs low) | 0.45 (0.22-0.91) | 0.026a | 1.50 (0.90-2.50) | 0.120 |

| PD-L1/CXCR3 (high vs low) | 2.15 (1.23-3.76) | 0.007b | 2.50 (1.45-4.31) | 0.001b |

| PD-1/CXCR3 (high vs low) | 1.98 (1.12-3.50) | 0.019a | 2.20 (1.28-3.78) | 0.004b |

| CXCR3/T-lymphocytes (high vs low) | 2.30 (1.30-4.07) | 0.004b | 2.00 (1.15-3.48) | 0.014b |

Multivariate logistic regression identified PD-1/CXCR3 and SIRI as independent predictors of stage IV lymphoma, whereas PD-L1/CXCR3 showed a weaker association. SII was not significantly associated (Figure 7, Table 13).

In subtype-specific ROC analysis, PD-1/CXCR3 demonstrated the highest diagnostic accuracy for stage IV disease in both DLBCL and CLL, whereas SIRI performed well in CLL but less strongly in DLBCL (Figure 8, Table 14).

In subtype-specific analysis, low PD-L1/CXCR3 expression was associated with longer OS in both CLL and DLBCL. High SIRI predicted improved OS in CLL but showed no significant impact in DLBCL (Figure 9, Table 15).

LPNs, including CLL, DLBCL, FL, and MCL, are a heterogeneous group of hematological malignancies with substantial clinical and prognostic variability[1]. In Egypt, the relatively high incidence of NHL, influenced by HCV prevalence and environmental exposures, highlights the need for reliable prognostic biomarkers to guide personalized treatment strategies[2,3]. The present study evaluated the prognostic significance of PD-L1/PD-1 co-expression, CXCR3-associated inflammatory signatures, and systemic inflammatory indices (SII and SIRI) in Egyptian patients with LPNs. Through integration of flow cytometry immunophenotyping with clinical and laboratory assessments, our goal was to clarify the role of these immune-inflammatory markers in disease staging, therapeutic response, and survival outcomes, thereby addressing a critical gap in localized biomarker evidence.

This discussion was organized thematically, integrating hematological, biochemical, immunophenotypic, and survival findings to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the prognostic significance of PD-L1/PD-1, CXCR3, SII, and SIRI. This approach emphasizes synergistic patterns and their clinical and biological relevance.

In our cohort, the mean age was 59.17 years with a slight female predominance (Table 1). CLL was the most common subtype, followed by DLBCL, FL, and MCL (Table 2). More than half of the patients presented with advanced-stage disease (stage III-IV), consistent with patterns reported in Egyptian cancer registries and hospital-based cohorts[11,12]. This distribution likely reflects systemic diagnostic delays common in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), where late presentation and limited access to specialized hematology services remain major barriers[11]. Although the sample size was modest, it was sufficient to detect significant differences in prognostic markers and survival outcomes, as confirmed by post hoc power analysis. The inclusion of four distinct LPN subtypes, comprehensive biomarker profiling, and tightly matched controls strengthened analytical power and generalizability. Nonetheless, external validation in larger, multicenter cohorts remains necessary.

Our findings highlight the value of incorporating immune-inflammatory biomarkers into diagnostic workflows, particularly in low-resource settings where molecular profiling is often unavailable. These results are most relevant to populations with a high burden of chronic infections, such as HCV, and restricted access to advanced molecular dia

The predominance of CLL and advanced-stage DLBCL in our cohort is consistent with previous epidemiological studies in Egypt, where CLL accounts for a major proportion of lymphoid malignancies and is most often diagnosed in older adults[13]. This contrasts with data from Western populations, where earlier detection is more common due to widespread screening, higher health literacy, and timely referrals[14]. For example, the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry in the United States reports that approximately 55% of NHLs are diagnosed at stage I-II, largely owing to routine health checks and greater access to imaging[15].

Egypt’s high prevalence of HCV has long been implicated in the pathogenesis of BCLs, particularly CLL and marginal zone lymphoma. Chronic antigenic stimulation from HCV drives clonal B-cell expansion and promotes lymphomagenesis[16,17]. This biological association is reinforced by studies showing regression of HCV-associated lymphomas following antiviral therapy, underscoring its role as a modifiable risk factor[18]. Our findings are consistent with these observations, suggesting that in endemic settings such as Egypt, HCV may serve not only as a risk factor but also as a potential therapeutic target.

The predominance of late-stage presentation in our cohort is consistent with regional Middle Eastern reports. A multicenter study from Saudi Arabia and Jordan found that more than 60% of patients with NHL presented with advanced-stage disease, frequently accompanied by B symptoms and extranodal involvement, closely paralleling our findings[19]. Comparable trends in North African countries further highlight the urgent need for early detection strategies and community-based awareness programs[20].

Collectively, these demographic and staging patterns underscore the need for accessible, cost-effective prognostic tools tailored to local epidemiology. Incorporating immune-inflammatory markers such as SII, SIRI, and flow cytometry immunophenotyping into routine practice may provide a practical approach for early risk stratification in resource-limited settings where PET-CT and molecular profiling are not readily available.

Patients with LPNs in our cohort exhibited classical hematologic and biochemical abnormalities reflecting tumor burden and systemic immune activation. The most consistent findings were anemia, thrombocytopenia, lymphocytosis, hypoalbuminemia, and elevated inflammatory and tumor-related markers, including CRP, ESR, ferritin, LDH, and B2M (Table 3). These alterations are characteristic of active disease and contribute to both staging and prognosis.

Anemia in LPNs arises through several mechanisms, including bone marrow infiltration by malignant cells, impaired erythropoiesis driven by inflammatory cytokines (notably interleukin-6), and increased hepcidin synthesis, which blocks iron mobilization from stores, a hallmark of anemia of chronic disease[21,22]. The elevated ferritin levels observed in our patients (Table 3) likely reflect both iron sequestration and acute-phase reactivity, serving as a surrogate for systemic inflammation[23]. High ferritin has been independently linked to a poor prognosis in lymphoma, particularly in DLBCL and HL, where it correlates with disease burden and cytokine-driven immune dysregulation[24].

LDH, a glycolytic enzyme released during rapid cell turnover, is a well-established prognostic marker in high-grade lymphomas. Our patients exhibited a 5-fold increase in LDH compared to controls (Table 3), consistent with enhanced anaerobic glycolysis (the Warburg effect) and tissue hypoxia in aggressive subtypes such as DLBCL and MCL[25]. Elevated LDH has been included in prognostic models like the international prognostic index and remains a surrogate for tumor mass and proliferative activity[26].

B2M, a component of the major histocompatibility complex class I complex, is another critical biomarker. In our cohort, B2M levels were significantly elevated (Table 3), particularly in CLL cases, where it has long been used to stratify risk and predict time to treatment[27]. B2M reflects tumor cell burden and is influenced by renal clearance; elevated levels have been linked to both poor progression-free survival (PFS) and OS in patients with CLL and NHL[28].

Hypoalbuminemia was prevalent in our patients (Table 3) and can be attributed to systemic inflammation, hepatic protein suppression, and increased capillary permeability. It has been widely recognized as an adverse prognostic factor in lymphomas, often reflecting malnutrition, inflammation, or advanced disease[29]. Elevated CRP and ESR levels further supported the inflammatory milieu in our cohort, contributing to immune suppression and remodeling of the tumor microenvironment.

Comparative studies from Europe and Asia echo these findings. Hamed Anber et al[30] reported elevated CRP and ferritin in aggressive BCLs, reinforcing their role in monitoring disease activity and relapse risk. In a Turkish cohort, Seo et al[31] found that high B2M and LDH levels were independently associated with poor outcomes in DLBCL, confirming their global relevance. Moreover, hypoalbuminemia has been integrated into the Glasgow Prognostic Score, a validated tool in hematological malignancies for survival prediction[32]. Collectively, these hematologic and biochemical alterations delineate disease burden and align with established prognostic systems. Their integration with immune-inflammatory biomarkers, as demonstrated in our study, may provide a more robust framework for individualized risk stratification and treatment planning.

In our study, both the SII and the SIRI were significantly elevated in patients with LPNs, particularly in DLBCL and CLL subtypes (Tables 4 and 6). These indices correlated with disease severity and adverse outcomes, with SIRI de

The SII, derived from neutrophil, lymphocyte, and platelet counts, integrates three key components of host-tumor interactions: Neutrophil-driven inflammation, lymphocyte-mediated antitumor immunity, and platelet-facilitated tumor progression. Elevated SII reflects enhanced inflammation with impaired immune surveillance. Neutrophils promote angiogenesis and metastasis through matrix metalloproteinases and vascular endothelial growth factor secretion, while lymphopenia indicates diminished cellular immunity[33]. Platelets contribute by shielding circulating tumor cells and supporting extravasation[34]. The SIRI, incorporating monocyte counts alongside neutrophils and lymphocytes, offers an additional layer of immunologic insight. Monocytes can differentiate into tumor-associated macrophages, which contribute to immune suppression, angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix remodeling within the tumor microenvironment[35]. Thus, high SIRI reflects both systemic inflammation and the recruitment of immunosuppressive myeloid cells, making it a powerful biomarker for tumor-host interactions.

In our cohort, SII was highest in DLBCL and FL, aligning with their aggressive biology, while SIRI peaked in CLL, a disease known for its immunomodulatory and monocyte-driven pathogenesis (Table 6). Interestingly, SIRI showed a paradoxical decline in stage IV cases (Table 7), possibly reflecting terminal immune exhaustion or apoptosis of monocyte subsets during late disease progression. Similar findings have been reported in murine models of lymphoid malignancy, where advanced-stage disease is characterized by impaired monopoiesis and myeloid cell depletion[36].

Global evidence reinforces our findings. In China, a large retrospective study of over 200 patients with DLBCL showed that high SII independently predicted poorer OS and PFS and outperformed NLR and PLR[37]. In Turkey, Gültürk et al[38] reported SIRI as an independent predictor of mortality in newly diagnosed DLBCL, correlating with high international prognostic index scores and extranodal disease. European cohorts similarly demonstrated that elevated SIRI and SII predict adverse outcomes in both indolent and aggressive lymphomas, supporting their applicability across diverse populations[39].

What sets our findings apart is the use of SII and SIRI in a Middle Eastern population, where delayed presentation, chronic infections (e.g., HCV), and limited imaging access often complicate traditional staging. Here, SIRI emerged as a sensitive, non-invasive tool for identifying stage IV disease, suggesting a pragmatic application in resource-limited settings. Its superior AUC (0.846) compared to SII (0.650) and strong correlation with PD-L1/CXCR3 co-expression (r = 0.58, Table 11) further underscore its biologic plausibility and clinical utility. Moreover, the post-treatment reduction in both indices (Table 5) implies their responsiveness to therapy and potential role in early relapse prediction. Such dynamic monitoring is especially valuable in settings where advanced imaging (e.g., PET-CT) is unavailable or unaffordable. In summary, SII and SIRI serve as robust, inexpensive, and clinically actionable markers of inflammation-driven tumor progression in LPNs. Their integration into routine hematological evaluation may enhance early risk stratification, treatment personalization, and long-term surveillance - particularly in under-resourced regions.

Our study demonstrated significantly elevated co-expression of PD-L1/CXCR3 and PD-1/CXCR3 on T lymphocytes in patients with LPNs compared to controls (Table 4). Both markers were closely associated with advanced disease stage (Table 7) and poorer survival outcomes (Tables 9 and 10). Importantly, their levels declined significantly after treatment (Table 5), indicating that these biomarkers not only mirror disease burden but also dynamically respond to therapy. Multivariate Cox regression further confirmed their independent prognostic value for both overall and EFS (Table 12), underscoring their potential utility in immunologic risk stratification.

The PD-1/PD-L1 axis is a key immune checkpoint regulating T-cell exhaustion in chronic infections and cancers. Engagement of PD-1 by PD-L1 induces T-cell anergy, reduces cytokine production (e.g., IFN-γ, interleukin-2), impairs cytotoxic function, and promotes apoptosis of effector T cells[40]. In LPNs, particularly DLBCL and CLL, PD-1 is frequently upregulated on CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, while PD-L1 is expressed by both tumor cells and tumor-associated macrophages, enabling immune escape[41,42].

CXCR3, a chemokine receptor classically linked to Th1-mediated responses, is expressed on activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and directs their migration toward IFN-γ-inducible ligands (CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11)[43]. In cancer, CXCR3 signaling plays a dual role. While it initially supports effector T-cell recruitment, chronic antigen exposure combined with PD-1 engagement can shift CXCR3+ T cells toward exhaustion, leading to the accumulation of dysfunctional effector memory subsets[44]. This exhausted CXCR3+PD-1+ T-cell phenotype has been described in several cancers, including lymphoma and melanoma, and is associated with impaired effector function and adverse survival outcomes[45].

Our findings reinforce this paradigm. The elevated PD-1/CXCR3 and PD-L1/CXCR3 co-expression observed in patients with stage IV disease (Table 7) likely reflects a dysfunctional immune microenvironment, where chronically stimulated T cells lose effector capacity yet persist due to CXCR3-mediated retention in lymphoid tissues. These exhausted T cells are refractory to reactivation and have been linked to resistance to immunochemotherapy and poor prognosis[46].

Previous studies support the prognostic value of these markers. Kiyasu et al[47] identified PD-L1 expression on tumor cells as an independent predictor of poor prognosis in DLBCL, particularly in non-germinal center B-cell-like subtypes. Xing et al[48] reported that PD-1 expression on peripheral and tissue-infiltrating T cells in CLL correlated with shorter PFS. More recently, Böttcher et al[49] demonstrated that CXCR3+PD-1+ T cells within lymphoma microenvironments show impaired proliferation and cytokine secretion, consistent with functional exhaustion.

Our study is among the first to report PD-1/CXCR3 and PD-L1/CXCR3 co-expression as composite markers in Egyptian patients with LPN. These dual markers provided high discriminatory power for stage IV disease (AUC = 0.872-0.959; Table 8) and retained prognostic value in multivariate models. Notably, their post-treatment reduction (Table 5) implies that they may serve not only as static prognostic markers but also as dynamic indicators of treatment response, with potential relevance for future immunotherapy stratification. Incorporating these immune checkpoint profiles into routine flow cytometry panels could enhance clinical decision-making, particularly in identifying patients who may benefit from PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade. While such therapies are still emerging in hematologic malignancies, our findings support their exploration in future trials targeting the exhausted CXCR3+ T-cell compartment.

Our study revealed marked dysregulation in CXCR3 expression across monocyte subsets in patients with LPNs, with the most profound changes observed in classical (CD14++CD16-) and intermediate (CD14++CD16+) monocytes (Table 4). Specifically, CXCR3 expression was significantly reduced on classical monocytes, while intermediate and non-classical subsets showed elevated expression compared to controls. This pattern varied by lymphoma subtype (Table 6) and disease stage (Table 7), highlighting a dynamic shift in monocyte polarization and chemokine receptor expression during lymphoma progression.

Monocytes are a heterogeneous population of innate immune cells that play crucial roles in tumor surveillance, inflammation, and tissue remodeling. Based on CD14 and CD16 expression, they are classified into classical monocytes (CD14++CD16-), which are pro-inflammatory and efficient phagocytes; intermediate monocytes (CD14++CD16+), which possess antigen-presenting and cytokine-producing functions; and non-classical monocytes (CD14+CD16++), which patrol the vasculature and participate in endothelial homeostasis[50].

In cancer, particularly hematologic malignancies, monocytes undergo phenotypic reprogramming in response to tumor-derived signals, leading to the expansion of immunosuppressive subpopulations and skewed chemokine receptor profiles[51]. Our finding of reduced CXCR3 on classical monocytes suggests their diminished migratory capacity toward IFN-γ-inducible chemokines (CXCL9-11), which are critical for initiating antitumor responses. Conversely, elevated CXCR3 on intermediate and non-classical monocytes may reflect a compensatory redistribution or chronic activation in the tumor microenvironment[51].

This phenotypic plasticity aligns with prior studies showing that monocyte subsets in patients with lymphoma are functionally altered. For instance, Jones et al[52] demonstrated CXCR3 downregulation in classical monocytes from patients with BCLs, accompanied by impaired chemotaxis and antigen presentation. In murine models of DLBCL, CXCR3 ligands produced in the tumor microenvironment selectively recruited intermediate monocytes, which subsequently differentiated into tumor-associated macrophages with immunosuppressive profiles[53].

Our data also show that CXCR3 expression on classical, intermediate, and non-classical monocytes decreased with advancing stage, particularly in stage IV disease (Table 7). This trend supports the hypothesis that during tumor progression, monocytes become increasingly dysfunctional, lose migratory responsiveness, and adopt a suppressive, pro-tumoral phenotype. Furthermore, CXCR3 expression on intermediate monocytes showed borderline predictive value for stage IV disease in ROC analysis (AUC = 0.720; Table 8), indicating its potential as a staging biomarker. Interestingly, CXCR3 expression on monocyte subsets did not significantly change post-treatment (Table 5), suggesting that monocyte reprogramming may be a relatively stable or treatment-resistant feature of LPNs. This finding is in line with studies by Jakubzick et al[54] and others, who reported persistent epigenetic modifications in monocyte precursors that sustain immunosuppressive traits despite systemic therapy.

Survival analysis revealed that high CXCR3 expression on classical and intermediate monocytes was associated with better OS (Figure 4, Table 9), suggesting a protective role of preserved CXCR3 signaling in monocyte-mediated immune surveillance. These results parallel findings in NHL, where preserved monocyte chemokine receptor profiles, including C-C motif chemokine receptor 2 and CXCR3, were linked to improved T-cell priming and reduced tumor microenvironment immunosuppression[55].

Together, our findings highlight the prognostic and biological relevance of CXCR3 reprogramming in monocyte subsets. The preferential depletion of CXCR3 on classical monocytes and accumulation in intermediate subsets reflects a tumor-induced remodeling of innate immunity, which may be leveraged in future immunomodulatory strategies targeting monocyte-macrophage differentiation and chemokine axis inhibition.

Our study underscores the utility of integrating immune-inflammatory and checkpoint-based biomarkers for enhanced prognostic assessment in LPNs. Among these, the SIRI, PD-1/CXCR3 co-expression, and CXCR3 expression on monocyte subsets independently predicted adverse outcomes (Tables 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13), with SIRI and PD-1/CXCR3 levels emerging as the most robust prognostic indicators in multivariate analysis. This layered approach reflects the complex interplay between systemic inflammation, tumor-induced immune exhaustion, and innate immune reprogramming in LPNs.

The predictive superiority of SIRI over SII (AUC 0.846 vs 0.650; Table 8) may stem from the inclusion of monocytes - a key driver of immunosuppression and tumor support in hematologic malignancies. Monocytes give rise to tumor-associated macrophages, which contribute to angiogenesis, matrix remodeling, and suppression of effector T-cell function. Elevated SIRI, therefore, not only indicates systemic inflammation but also mirrors the expansion of suppressive myeloid populations, which are known to predict poor response to chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors[56,57].

The PD-1/CXCR3 co-expression on T cells provided strong prognostic discrimination for both OS and EFS (Figure 4, Table 10), particularly in patients with advanced-stage disease. This phenotype, characterized by impaired proliferation, cytokine secretion, and cytotoxicity, represents a hallmark of T-cell exhaustion, as described in chronic infections and cancers[58]. Notably, our study found that PD-1/CXCR3 was a stronger predictor of poor outcomes than traditional biomarkers such as LDH or ferritin. This suggests that immune exhaustion phenotypes may capture disease aggressiveness and host tolerance mechanisms more effectively than metabolic surrogates.

Furthermore, CXCR3 expression on classical and intermediate monocytes independently predicted OS (Table 12). High CXCR3 expression on these subsets was associated with better prognosis, possibly reflecting a preserved capacity for immune cell trafficking and anti-tumor responses. By contrast, CXCR3 downregulation may mark terminal monocyte exhaustion or conversion into non-inflammatory tumor-associated macrophages - a process linked to resistance to chemotherapy and immune evasion[59].

When considered together, these markers represent distinct but complementary immunologic domains: SIRI reflects systemic inflammatory burden and monocyte activation, PD-1/CXCR3 captures adaptive T-cell dysfunction and immune checkpoint exhaustion, and monocyte CXCR3 indicates the integrity of innate immune surveillance. This multimodal strategy aligns with emerging trends in integrative prognostication; wherein immune and inflammatory markers are layered onto classical clinical indices. For example, recent studies in DLBCL have combined NLR, SIRI, and PD-L1 expression into immune-clinical scores that outperform international prognostic index alone in predicting treatment outcomes and survival[60,61].

Our ROC-based analysis (Table 8) and Kaplan-Meier survival curves (Figure 4) confirm the clinical relevance of such biomarker integration. Importantly, many of these markers, particularly SIRI and flow cytometry co-expression indices, are cost-effective, reproducible, and readily obtainable, making them attractive for implementation in resource-limited settings such as Egypt and the broader Middle East and North Africa region. In summary, the combined use of SIRI, PD-1/CXCR3, and monocyte CXCR3 expression provides a robust, immunologically grounded framework for risk stratification in LPNs. This approach may complement or even supersede traditional staging tools in certain clinical contexts and should be explored further in prospective, multicenter studies to validate its generalizability and utility in therapeutic decision-making[61].

The findings of this study carry substantial clinical relevance, particularly in LMICs such as Egypt, where access to advanced diagnostic modalities remains limited. The immune-inflammatory biomarkers evaluated herein, SIRI, SII, PD-1/CXCR3, and monocyte CXCR3, are derived from routine hematological and flow cytometry panels, which are widely available, inexpensive, and technically feasible across most tertiary and even secondary care hospitals. In the absence of PET, next-generation sequencing, or high-throughput gene expression profiling, many hematology units in resource-constrained settings face challenges in risk-stratifying patients beyond basic clinical staging. Traditional tools like the international prognostic index and Ann Arbor staging, while useful, do not capture the dynamic host-tumor immune interactions that profoundly influence disease progression, treatment response, and survival. The incorporation of functional immune markers such as SIRI and PD-1/CXCR3 co-expression may therefore offer a practical bridge between resource availability and precision oncology.

These markers are particularly appealing for LMIC contexts due to several advantages: (1) Cost-effectiveness: SIRI and SII are calculated from complete blood counts, costing under 1 dollar per test in most public health systems; (2) Flow cytometry markers like PD-1 and CXCR3 are part of standard antibody panels in immunophenotyping labs, with no need for specialized infrastructure; (3) Reproducibility and standardization: These indices are based on objective, quantitative values, minimizing inter-observer variability compared to morphologic scoring or clinical staging; and (4) Dynamic utility: Their ability to track pre- and post-treatment changes (Table 5) suggests potential use in early treatment response assessment and relapse prediction. Similar approaches have been validated in other LMICs. In India and Pakistan, several hematology centers have incorporated NLR, PLR, and SIRI into routine lymphoma workflows with demonstrable improvements in prognostication, especially where PET/CT was unavailable[62,63]. A multicenter study in sub-Saharan Africa also demonstrated that inflammatory biomarkers, including CRP and ferritin, predicted survival in patients with lymphoma where molecular diagnostics were inaccessible[64]. Importantly, our study also illustrates the added value of combining multiple low-cost markers, for example, using SIRI for systemic inflammation, PD-1/CXCR3 for adaptive immune exhaustion, and monocyte CXCR3 for innate surveillance integrity. This layered approach, while inexpensive, provides a more nuanced risk portrait than any single biomarker, particularly in CLL and DLBCL, which dominated our cohort.

From a policy and public health standpoint, the adoption of such biomarkers may also assist in resource triage, for instance, identifying high-risk patients for closer monitoring, hospitalization, or referral to specialized centers. This is particularly critical in overburdened oncology systems, where bed availability and chemotherapy access are constrained. In conclusion, the immunologic and inflammatory biomarkers identified in this study represent scalable, accessible, and biologically meaningful tools for the prognostic assessment of LPNs in Egypt and similar LMIC settings. Future research should focus on external validation across diverse populations, integration into prognostic models, and implementation science frameworks to optimize clinical adoption[65].

This study is among the first to comprehensively evaluate PD-L1/PD-1 co-expression with CXCR3 and systemic inflammatory indices (SII and SIRI) in Egyptian patients with LPNs. The high incidence of NHL in Egypt, partly at

This study had several limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the findings. First, it was conducted at a single tertiary center in Egypt, which may limit the generalizability of the results to broader populations or different healthcare systems. Although a range of lymphoma subtypes and disease stages were included, larger multicenter studies are needed to validate the prognostic performance of SIRI, SII, PD-1/CXCR3, and monocyte CXCR3 expression in more diverse cohorts. Second, while our flow cytometry analysis provided valuable information on immune checkpoint and chemokine receptor expression, we did not perform functional immune assays such as cytokine profiling or in vitro exhaustion analyses, which could have enriched our understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying immune dysfunction in LPNs. Third, our follow-up period was relatively short, which may limit our ability to draw definitive conclusions about the long-term prognostic value of these biomarkers, particularly in predicting relapse or progression beyond first-line treatment. Additionally, molecular profiling was not available in this cohort, precluding integration of immunologic markers with key genetic alterations such as v-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene, B-cell lymphoma 2, or tumor protein p53 status. Therapeutic heterogeneity, while reflective of real-world clinical practice, may have also introduced confounding effects, as patients received different treatment regimens based on subtype and available resources, potentially influencing biomarker expression and outcomes. Furthermore, while we propose that these biomarkers are affordable and suitable for resource-limited settings, we did not formally assess their im

These findings not only validate the prognostic role of PD-L1/PD-1-CXCR3 co-expression and systemic inflammation indices in Egyptian patients but also provide a model for integrating immune phenotyping into routine hematology-oncology practice. This integrative biomarker approach could be readily adapted in other resource-limited settings, offering both prognostic precision and cost-effectiveness.

Our study provides robust evidence that combining immune checkpoint co-expression markers, such as PD-1/CXCR3 and PD-L1/CXCR3, with systemic inflammatory indices like SIRI offers a powerful, accessible approach to prognostic stratification in LPNs. These markers not only correlated with disease stage and treatment response but also independently predicted survival, highlighting their potential utility in both clinical risk assessment and therapeutic decision-making. Importantly, their availability through standard laboratory and flow cytometry platforms makes them feasible tools for implementation in low-resource settings such as Egypt, where access to advanced imaging and molecular profiling is often limited. Together, these findings support the integration of immune-inflammatory biomarkers into routine hematologic practice to improve patient outcomes and enable more personalized care across diverse healthcare environments.

| 1. | Sabattini E, Bacci F, Sagramoso C, Pileri SA. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues in 2008: an overview. Pathologica. 2010;102:83-87. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Mahmoud AE, AbdelKarim K, Abdelhakim KN, El Ghamry WR, Hussein MM, Diaa Sherif DEDM. A retrospective analysis of epidemiology and clinical outcome of Hodgkin lymphoma patients in the clinical oncology department in Ain shams university hospitals in Egypt. Ain Shams Med J. 2022;73:521-529. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Paes FM, Kalkanis DG, Sideras PA, Serafini AN. FDG PET/CT of extranodal involvement in non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin disease. Radiographics. 2010;30:269-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mondello P, Younes A. Emerging drugs for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2015;15:439-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rotondi M, Lazzeri E, Romagnani P, Serio M. Role for interferon-gamma inducible chemokines in endocrine autoimmunity: an expanding field. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26:177-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Reynders N, Abboud D, Baragli A, Noman MZ, Rogister B, Niclou SP, Heveker N, Janji B, Hanson J, Szpakowska M, Chevigné A. The Distinct Roles of CXCR3 Variants and Their Ligands in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cells. 2019;8:613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liu J, Chen Z, Li Y, Zhao W, Wu J, Zhang Z. PD-1/PD-L1 Checkpoint Inhibitors in Tumor Immunotherapy. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:731798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 52.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hu B, Yang XR, Xu Y, Sun YF, Sun C, Guo W, Zhang X, Wang WM, Qiu SJ, Zhou J, Fan J. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:6212-6222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1414] [Cited by in RCA: 1589] [Article Influence: 132.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Topkan E, Kucuk A, Ozdemir Y, Mertsoylu H, Besen AA, Sezen D, Bolukbasi Y, Pehlivan B, Selek U. Systemic Inflammation Response Index Predicts Survival Outcomes in Glioblastoma Multiforme Patients Treated with Standard Stupp Protocol. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020:8628540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Azzazi M, Mohamed M, Mousa M, Mohammed R, Eldin Youssef S. Multicentre study of hepatitis C virus status in Egyptian patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with assessment of patients’ immunological state. Egypt J Haematol. 2017;42:19-30. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Ibrahim AS, Khaled HM, Mikhail NN, Baraka H, Kamel H. Cancer incidence in egypt: results of the national population-based cancer registry program. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;2014:437971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 32.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Khalifa MM, Zaki NE, Nazier AA, Moussa MA, Haleem RA, Rabie MA, Mansour AR. Prognostic significance of microRNA 17-92 cluster expression in Egyptian chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2021;33:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ragab SM, El-Hawy MA, Mahmoud AA, Bayomi AR, Abd El-Hamid ME. The Epidemiological Study of Children with Malignant Disorders in the Pediatric Department at Menoufia University Hospital, Menoufia, Egypt during the Last Fifteen Years. Iran J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2024;14:1-16. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Smith A, Crouch S, Lax S, Li J, Painter D, Howell D, Patmore R, Jack A, Roman E. Lymphoma incidence, survival and prevalence 2004-2014: sub-type analyses from the UK's Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:1575-1584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 29.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mele A, Pulsoni A, Bianco E, Musto P, Szklo A, Sanpaolo MG, Iannitto E, De Renzo A, Martino B, Liso V, Andrizzi C, Pusterla S, Dore F, Maresca M, Rapicetta M, Marcucci F, Mandelli F, Franceschi S. Hepatitis C virus and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas: an Italian multicenter case-control study. Blood. 2003;102:996-999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ibrahim A, Mikhail N. The evolution of cancer registration in Egypt: From proportions to population-based incidence rates. SECI Oncol J. 2015. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Viswanatha DS, Dogan A. Hepatitis C virus and lymphoma. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1378-1383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hermine O, Lefrère F, Bronowicki JP, Mariette X, Jondeau K, Eclache-Saudreau V, Delmas B, Valensi F, Cacoub P, Brechot C, Varet B, Troussard X. Regression of splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes after treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:89-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 597] [Cited by in RCA: 562] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Perry AM, Diebold J, Nathwani BN, MacLennan KA, Müller-Hermelink HK, Bast M, Boilesen E, Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD. Relative frequency of non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes in selected centres in North Africa, the middle east and India: a review of 971 cases. Br J Haematol. 2016;172:699-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Madihi S, Bouafi H, Boukaira S, Bennani S, Benani A. Epidemiological trends of hematological malignancies in North Africa: Recent insights. Bull Cancer. 2025;S0007-4551(25)00289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Weiss G, Goodnough LT. Anemia of chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1011-1023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2133] [Cited by in RCA: 2219] [Article Influence: 105.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nemeth E, Rivera S, Gabayan V, Keller C, Taudorf S, Pedersen BK, Ganz T. IL-6 mediates hypoferremia of inflammation by inducing the synthesis of the iron regulatory hormone hepcidin. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1271-1276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 862] [Article Influence: 39.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shen Z, Zhang S, Zhang M, Hu L, Sun Q, He C, Yan D, Ye J, Zhang H, Wang L, Gu W, Miao Y, Liu Q, Ouyang C, Zhu J, Wang C, Zhu T, Huang S, Sang W. The Addition of Ferritin Enhanced the Prognostic Value of International Prognostic Index in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:823079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hong J, Woo HS, Kim H, Ahn HK, Sym SJ, Park J, Ahn JY, Cho EK, Shin DB, Lee JH. Anemia as a useful biomarker in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP immunochemotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:1569-1575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hong J, Yoon HH, Ahn HK, Sym SJ, Park J, Park PW, Ahn JY, Park S, Cho EK, Shin DB, Lee JH. Prognostic role of serum lactate dehydrogenase beyond initial diagnosis: a retrospective analysis of patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Acta Haematol. 2013;130:305-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ziepert M, Hasenclever D, Kuhnt E, Glass B, Schmitz N, Pfreundschuh M, Loeffler M. Standard International prognostic index remains a valid predictor of outcome for patients with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2373-2380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 446] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wierda WG, O'Brien S, Wang X, Faderl S, Ferrajoli A, Do KA, Cortes J, Thomas D, Garcia-Manero G, Koller C, Beran M, Giles F, Ravandi F, Lerner S, Kantarjian H, Keating M. Prognostic nomogram and index for overall survival in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:4679-4685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Döhner H, Estey EH, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Büchner T, Burnett AK, Dombret H, Fenaux P, Grimwade D, Larson RA, Lo-Coco F, Naoe T, Niederwieser D, Ossenkoppele GJ, Sanz MA, Sierra J, Tallman MS, Löwenberg B, Bloomfield CD; European LeukemiaNet. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2010;115:453-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2353] [Cited by in RCA: 2602] [Article Influence: 162.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gupta D, Lis CG. Pretreatment serum albumin as a predictor of cancer survival: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr J. 2010;9:69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1011] [Cited by in RCA: 1097] [Article Influence: 68.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hamed Anber N, El-Sebaie AH, Darwish NHE, Mousa SA, Shamaa SS. Prognostic value of some inflammatory markers in patients with lymphoma. Biosci Rep. 2019;39:BSR20182174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Seo S, Hong JY, Yoon S, Yoo C, Park JH, Lee JB, Park CS, Huh J, Lee Y, Kim KW, Ryu JS, Kim SJ, Kim WS, Yoon DH, Suh C. Prognostic significance of serum beta-2 microglobulin in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. Oncotarget. 2016;7:76934-76943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Proctor MJ, Morrison DS, Talwar D, Balmer SM, Fletcher CD, O'Reilly DS, Foulis AK, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. A comparison of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with cancer. A Glasgow Inflammation Outcome Study. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2633-2641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 620] [Article Influence: 41.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Templeton AJ, Ace O, McNamara MG, Al-Mubarak M, Vera-Badillo FE, Hermanns T, Seruga B, Ocaña A, Tannock IF, Amir E. Prognostic role of platelet to lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:1204-1212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 511] [Cited by in RCA: 522] [Article Influence: 43.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Labelle M, Begum S, Hynes RO. Direct signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an epithelial-mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:576-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1180] [Cited by in RCA: 1465] [Article Influence: 97.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Malesci A, Laghi L, Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:399-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1778] [Cited by in RCA: 3079] [Article Influence: 342.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Mitroulis I, Kalafati L, Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T. Myelopoiesis in the Context of Innate Immunity. J Innate Immun. 2018;10:365-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Wang Z, Zhang J, Luo S, Zhao X. Prognostic Significance of Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index in Patients With Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:655259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Gültürk E, Kapucu K, Akkaya E, Yılmaz D, Hindilerden F. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index and Hodgkin Lymphoma: an Underexplored Relationship. Acta Oncol Tur. 2023;56:259-271. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 39. | Wang S, Ma Y, Sun L, Shi Y, Jiang S, Yu K, Zhou S. Prognostic Significance of Pretreatment Neutrophil/Lymphocyte Ratio and Platelet/Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9651254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Okazaki T, Honjo T. The PD-1-PD-L pathway in immunological tolerance. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:195-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 574] [Article Influence: 28.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Thibult ML, Mamessier E, Gertner-Dardenne J, Pastor S, Just-Landi S, Xerri L, Chetaille B, Olive D. PD-1 is a novel regulator of human B-cell activation. Int Immunol. 2013;25:129-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Sagiv-Barfi I, Kohrt HE, Czerwinski DK, Ng PP, Chang BY, Levy R. Therapeutic antitumor immunity by checkpoint blockade is enhanced by ibrutinib, an inhibitor of both BTK and ITK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E966-E972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 32.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Groom JR, Luster AD. CXCR3 ligands: redundant, collaborative and antagonistic functions. Immunol Cell Biol. 2011;89:207-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 624] [Cited by in RCA: 763] [Article Influence: 50.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Shin DS, Zaretsky JM, Escuin-Ordinas H, Garcia-Diaz A, Hu-Lieskovan S, Kalbasi A, Grasso CS, Hugo W, Sandoval S, Torrejon DY, Palaskas N, Rodriguez GA, Parisi G, Azhdam A, Chmielowski B, Cherry G, Seja E, Berent-Maoz B, Shintaku IP, Le DT, Pardoll DM, Diaz LA Jr, Tumeh PC, Graeber TG, Lo RS, Comin-Anduix B, Ribas A. Primary Resistance to PD-1 Blockade Mediated by JAK1/2 Mutations. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:188-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 893] [Cited by in RCA: 1052] [Article Influence: 116.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Wherry EJ, Kurachi M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:486-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2189] [Cited by in RCA: 3493] [Article Influence: 317.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 46. | Hashimoto M, Kamphorst AO, Im SJ, Kissick HT, Pillai RN, Ramalingam SS, Araki K, Ahmed R. CD8 T Cell Exhaustion in Chronic Infection and Cancer: Opportunities for Interventions. Annu Rev Med. 2018;69:301-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 461] [Cited by in RCA: 511] [Article Influence: 63.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Kiyasu J, Miyoshi H, Hirata A, Arakawa F, Ichikawa A, Niino D, Sugita Y, Yufu Y, Choi I, Abe Y, Uike N, Nagafuji K, Okamura T, Akashi K, Takayanagi R, Shiratsuchi M, Ohshima K. Expression of programmed cell death ligand 1 is associated with poor overall survival in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2015;126:2193-2201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Xing K, Zhou P, Li J, Liu M, Zhang WE. Inhibitory Effect of PD-1/PD-L1 and Blockade Immunotherapy in Leukemia. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2022;25:1399-1410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Böttcher JP, Beyer M, Meissner F, Abdullah Z, Sander J, Höchst B, Eickhoff S, Rieckmann JC, Russo C, Bauer T, Flecken T, Giesen D, Engel D, Jung S, Busch DH, Protzer U, Thimme R, Mann M, Kurts C, Schultze JL, Kastenmüller W, Knolle PA. Functional classification of memory CD8(+) T cells by CX3CR1 expression. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |