Published online Jan 24, 2026. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v17.i1.112369

Revised: August 13, 2025

Accepted: November 27, 2025

Published online: January 24, 2026

Processing time: 179 Days and 19.7 Hours

An observed correlation between increased colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence in patients with obesity [body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2] has been identified in past literature. However, there has been limited data in recent decades. This, along with a dramatic global increase in obesity rates, exposure to environmental and lifestyle risk factors for CRC development, and large updates to the proposed biological mechanisms underpinning this relationship, warrants an updated review of recent data between CRC and obesity.

To determine if an updated correlation exists between obesity and the risk of CRC development.

We evaluated recent data, synthesising pooled estimate effects to determine if an updated correlation exists between obesity and CRC. Observational studies were identified from a range of databases (PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus and the Coch

In a pooled sample size of 83506 male participants obtained from six observational studies, a significant positive correlation between obesity and CRC in

Obesity, diagnosed by a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, significantly increases the risk of CRC incidence compared to those of a healthy BMI underscoring the importance of focused strategies to prevent obesity as a modifiable risk factor to reduce CRC incidence.

Core Tip: This systematic review and meta-analysis identify obesity as a modifiable risk factor for colorectal cancer (CRC) in both men and women. The risk is further heightened by associated lifestyle factors such as poor diet, physical inactivity, and the presence of comorbidities, including diabetes. These elements contribute synergistically to the development of CRC, highlighting the importance of recognising obesity not just as a health concern but as a cancer-promoting condition. Implementing earlier and targeted screening strategies for CRC in obese individuals can play a key role in reducing incidence and improving outcomes through earlier detection and intervention.

- Citation: Leung LJCL, Sharma RS, Cheng B, Akalanka HK, Gopalan V. Obesity and colorectal cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Clin Oncol 2026; 17(1): 112369

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v17/i1/112369.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v17.i1.112369

The obesity epidemic remains one of the most significant public health concerns of this century. Being a complex condition with significant social and psychological dimensions, obesity impacts all ages and socioeconomic groups, affecting almost 1 billion individuals globally[1]. Since 1975, rates of obesity have increased disproportionately to population growth[2]. This past decade, despite an increased recognition of obesity’s global health and burden[3], obesity rates continue to grow dramatically, extending to even the most already obese-prevalent societies[4].

Obesity is closely associated with a plethora of comorbidities, exacerbating its impact on health and quality of life. Co-morbidities include, but are not limited to, coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), chronic kidney disease, metabolic syndrome, and cancer[4,5]. Of particular concern, obesity has been observed as a leading risk factor for various cancers in the colon, rectum, breast, and oesophagus[6,7].

Colorectal cancer (CRC) has the third highest incidence rate and second highest mortality rate out of all known cancers[6]. The aetiology of CRC is multifaceted, with extensive research suggesting cellular mechanisms linking obesity to CRC, including inflammatory dysregulation, altered gut microbiome, and insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) hy

Previous reviews investigating the relationship between obesity and CRC provide strong corroborative evidence. Ning and colleagues found that from 56 observational studies, obese individuals, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 30 kg/m2, had a 41% increased risk of developing CRC compared to those within the healthy BMI range[13]. Moghaddam et al’s study[14] also suggested that, from 31 studies, obese males (≥ 30 kg/m2) possessed a 1.41 increased risk of CRC [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.30-1.51] compared to healthy weight males, while obese females displayed no differences. With global obesity rates exceeding 16% among adults and 8% among children and adolescents, affecting approximately 878 million and 128 million individuals, respectively, the relationship between obesity and CRC raises serious concerns, suggesting a potential surge in CRC cases in the coming years[15].

Of the previously identified systematic reviews, studies published up to February 2008 were used to evaluate the re

Therefore, this study aims to evaluate recent data to determine if an updated correlation exists between obesity and CRC, considering the rising prevalence of obesity and evolving risk factors while exploring the underlying molecular mechanisms driving these associations.

This systematic review and meta-analysis are reported according to the PRISMA guidelines[17].

Studies were sourced from PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus and the Cochrane database by two independent investigators (Leung LJC and Sharma RS), using key terms including: Obesity, BMI, CRC, colorectal carcinoma, bowel cancer and registry. Additional studies were also obtained via snowballing, identifying papers of interest from the reference list of both included papers. Investigated studies were published between March 2008 and August 2024. The search terms used for each database can be found in the Supplementary Table 1.

The inclusion criteria: (1) Observational studies (cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control) investigating the relationship between obesity and CRC or colon cancer; (2) Obesity patient categorisation follows the WHO obesity diagnostic criteria (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 internationally (17), BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 for individuals of Asian-Pacific descent[18]); (3) Cases of CRC or colon cancer are received from registry data; (4) odds ratios (OR), hazard ratios (HR) or relative risks (RR) with 95%CI were presented; (5) Includes a reference group who possessed a healthy BMI (internationally, 18.5-24.9 kg/m2; Asian-pacific descent, 18.5-22.9 kg/m2)[18,19]; and (6) Studies published in English.

The exclusion criteria: (1) Case-reports, review-articles, opinion pieces, non-English studies, grey literature and un

Following full-text review, the remaining studies underwent data extraction by two independent reviewers (Leung LJC and Sharma RS), which included: Author names, publication date, data registry source, obesity definition utilised, sample size, sex proportion, age range (including average), follow-up duration (years) and adjusted covariates. For the topic of this review, the term ‘sex’ was defined as the biological attributes associated with the chromosomal genotype of the patient and was recorded based on self-report of the patient. The incidence ratios, such as HR, OR and RR were also obtained along with the 95%CI.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) is a quality assessment tool used for non-randomised studies in meta-analyses[20]. The NOS was chosen as it is considered an easy and convenient quality-assessment tool with established content validity and inter-rater reliability. As all included studies were cohort and case-control studies, two modified criteria of the NOS were used for each study type. Using this tool, two independent reviewers evaluated each study, awarding stars out of a possible nine. Studies were classified as either high quality (≥ 7 stars) or low quality (< 7 stars)[21]. Stars were assigned based on three categories: (1) The quality of cohort selection; (2) The comparability of obese and non-obese cohorts; and (3) The methods used for assessment of CRC. Any discrepancies in quality assessment were resolved by consensus between the two reviewers.

All statistical data analysis was conducted on RStudio version 2024.4.2.764[21] using the meta-analysis package ‘metafor’[22]. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using τ2, I2 and the Cochran Q test, which quantifies the variability of results across studies, and publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots, which are included in the Supplementary Figures 1 and 2. To minimise heterogeneity, two separate meta-analyses were performed to compare the association between obesity and CRC development in males and females. A random-effects model was applied when significant heterogeneity was detected, whereas a fixed-effects model was used when no heterogeneity was present. Studies not included in the meta-analysis were reviewed and synthesised qualitatively.

An initial database search yielded 368 papers, of which 107 were removed as duplicates. An additional 243 records were excluded during title and abstract screening. Among the 18 studies selected for full-text review, 3 were excluded: 2 for not directly investigating the association between obesity and CRC, and 1 for not utilising a cancer registry to identify CRC cases. Overall, 15 studies satisfied the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. The full details of this screening process can be found in the Supplementary Figure 3.

The included studies had a combined sample size of 12871700 participants. Among these, two were case-control studies[23,24] and 13 were cohort studies[25-37] (Supplementary Table 2). Sample sizes ranged from 929 to 1368 participants for the case-control studies and from 708 to 9959605 participants for the cohort studies. Additional study details are presented in the Supplementary Table 3. Of the 15 studies, 14 were assessed as high quality[24-29,31-37], while one study was determined to be of low quality[30]. The results for each study can be found in the Supplementary Tables 3 and 4.

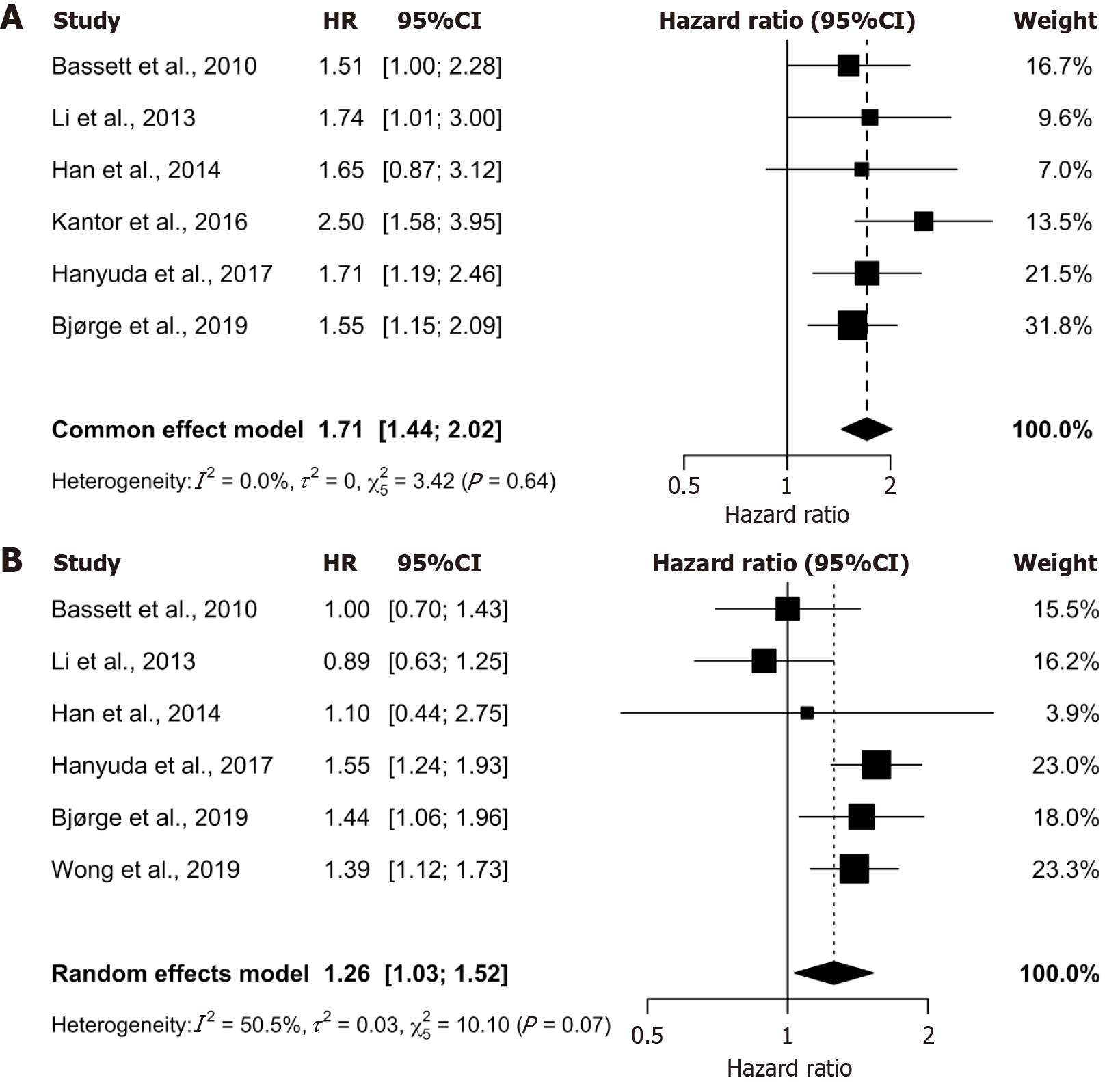

This systematic review identified seven observational studies (all cohort studies) with comparable incidence ratios and study design to include in the meta-analysis to quantitatively assess the relationship between obesity and CRC[27,29-32,34,35]. This analysis was stratified by sex and presented graphically as forest plots (Figure 1). Ultimately, six studies were included in the male meta-analysis[27,29-32,35] (Figure 1A) and six were included in the female meta-analysis[27,29,30,32,34,35] (Figure 1B), encompassing 83506 male and 152043 female participants.

The meta-analysis revealed a significant positive association between obesity and CRC for both sexes. Obese men demonstrated a 1.71-fold increased risk of CRC (HR 1.71, 95%CI: 1.44-2.02), while obese women showed a 1.26-fold increased risk (HR 1.26, 95%CI: 1.03-1.53), compared to their normal BMI counterparts. The 95%CI for both analyses excluded 1, confirming statistical significance. Both the male and female meta-analyses possess a τ2 of close to, or equal to 0 (0 and 0.0298, respectively) as well as non-significant Cochrane Q P values (0.64 and 0.07, respectively), which indicates non-significant heterogeneity for both demographics. Furthermore, the male meta-analysis reveals an I2 value of 0, indicating low to no heterogeneity (Figure 1A), while the female meta-analysis indicates potential moderate heterogeneity with an I2 value of 50% (Figure 1B). These findings suggest a consistent relationship between obesity and CRC risk, with a more pronounced effect observed in males. The low heterogeneity in the male analysis strengthens the reliability of this finding, whereas the moderate heterogeneity in the female analysis warrants further exploration of potential sources of variation.

Among males, five of the six included studies reported a positive correlation between obesity and CRC incidence, with HRs ranging from 1.6 to 2.5[27,29,31,32,35] (Figure 1A). Notably, one study by Han et al[30], which contributed the lowest weight within the male meta-analysis, found a non-statistically significant association between obesity and CRC (Figure 1A). Among females, three of the six studies revealed a positive association, with HR ranging from 1.4 HR to 1.6 HR[30,32,34,35], while the remaining three reported no measurable effect[27,29,30] (Figure 1B).

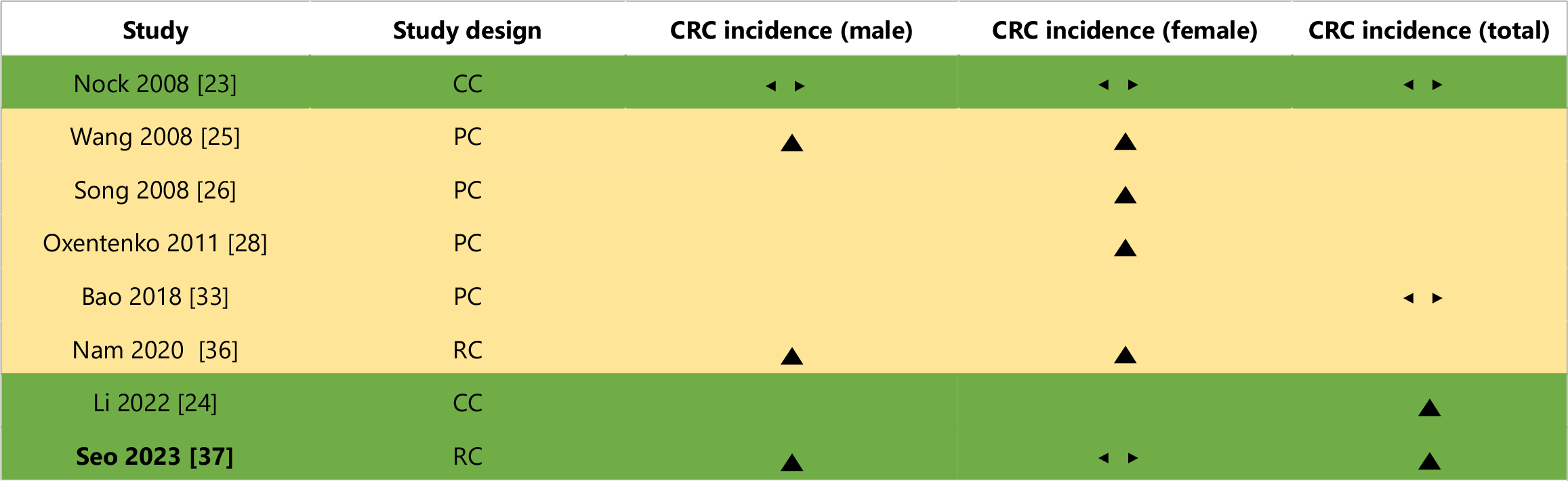

A graphical summary of the studies excluded from the meta-analysis is presented in Figure 2, adapted from Boon and Thompson[38]. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Use of different measures of association, such as OR and RR[23-25,28,33]; (2) Use of alternative obesity measures in addition to the WHO obesity diagnostic criteria[26,36]; and (3) Methodological limitations that prevented accurate comparison with studies included in the meta-analysis[37].

This systematic review identified one case-control study exploring the relationship between obesity and CRC across various age demographics[23]; However, this study was unable to find a statistically significant 95%CI for any of these demographics. This may be attributed to methodological limitations, including the use of self-reported weight and height to estimate BMI retrospectively for each age decade, potentially introducing recall bias and data misrepresentation. Additionally, restricting controls to individuals aged 40 years or older may have further skewed the results.

One cohort study was also identified that investigated CRC risk for obese individuals at various ages[24]. This study found that, at ages 20 and 30, statistically significant positive correlations were identified with incidence ratios of (OR 1.44, 95%CI: 1.18-1.75) and (RR 2.06, 95%CI: 1.25-3.40), respectively. While this study possesses too few age demographics to accurately determine the link between obesity, age and CRC, they have reported a potential increased susceptibility to obesity-induced CRC in older ages.

Ultimately, no overall conclusion about obesity, age and CRC incidence can be made from these two studies, and more research will be required to properly investigate this relationship.

This systematic review identified three cohort studies that investigated and compared the association between different severities of obesity and CRC[25,26,28]. Wang reported a positive link between obesity and CRC for all levels of obesity for both men and women, observing a greater increased risk for CRC for those categorised in the severe obesity BMI range (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2)[25]. This was reflected by Oxentenko et al[28], which found an increasingly positive link between obesity and CRC as the obesity BMI reached the severe category. Song found a similar trend, identifying the correlation between obesity and CRC to be greater in those in the severe obesity category than those at baseline obesity; however, the incidence ratio of middle severity and CRC was found to be statistically insignificant[26].

Another cohort study was identified in this systematic review that investigated two separate forms of obesity and their link to CRC (general obesity with abdominal obesity and general obesity without abdominal obesity)[36]. Nam et al[36] reported no link between general obesity without abdominal obesity for men, women and combined. However, a statistically significant positive correlation was identified between general obesity with abdominal obesity and CRC for all demographics.

This systematic review identified one cohort study by Bao et al[33] that investigated the link between obesity and both colon cancer and rectal cancer independently. However, for both colon cancer and rectal cancer, no statistically significant ORs were found.

This systematic review identified one retrospective cohort study by Seo et al[37] that investigated obesity status in patients at a four-year interval (from 2005 to 2009) and how it affected their CRC development risk. Seo’s study found that those who were consistently obese during this four-year interval possessed an increased risk of CRC development of 1.08 HR (95%CI: 1.06-1.11) compared to those who were consistently non-obese[37]. Interestingly, this study observed that participants whose weight changed from obese to non-obese and non-obese to obese saw no statistically significant increase in CRC risk; however, these findings were later justified by the authors to be due to an insufficient follow-up period.

Overall, this study was unable to make a definitive conclusion whether weight gain or loss affected an individual’s risk for CRC development, highlighting the need for further research with longer follow-up durations.

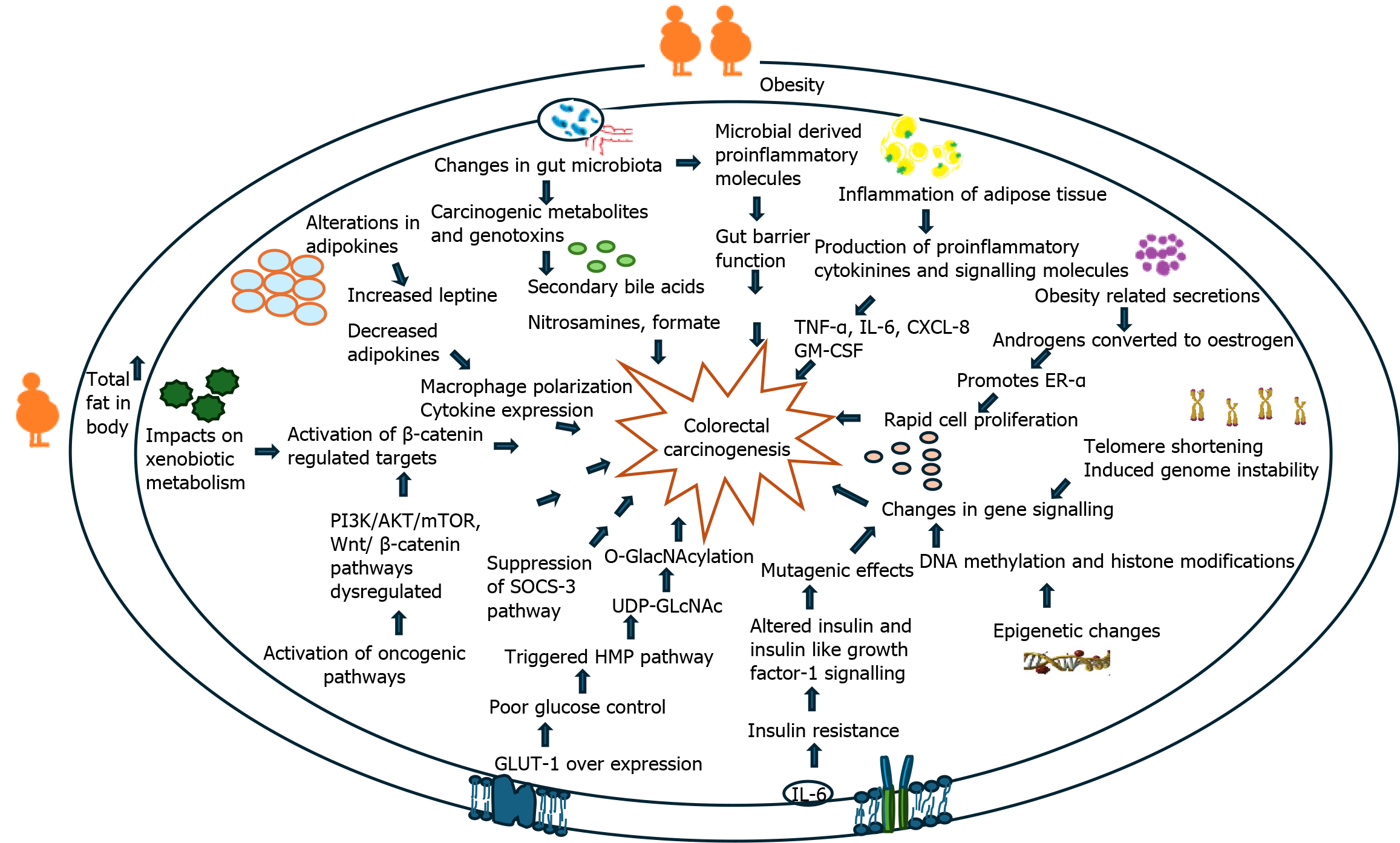

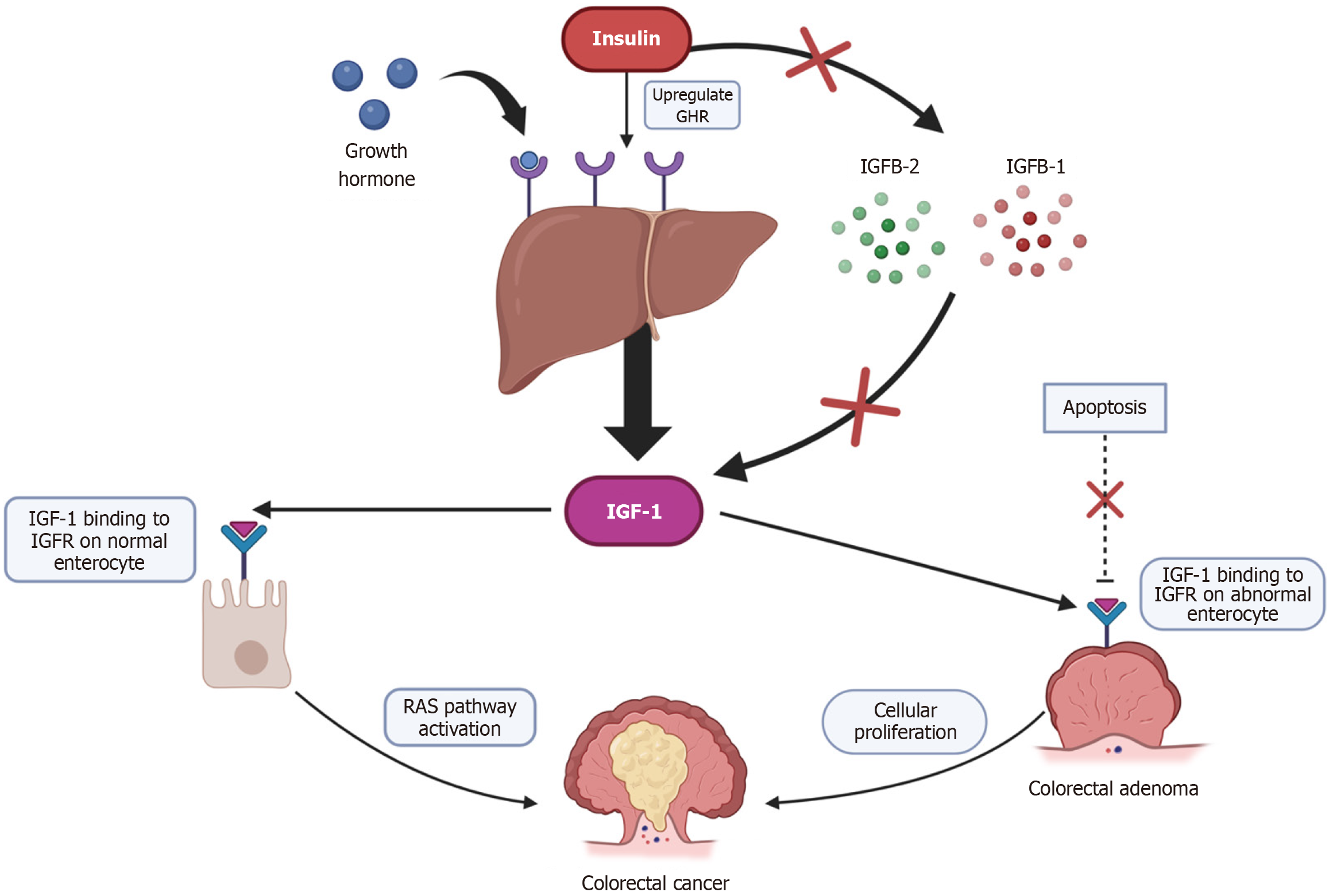

The specific biological mechanism describing the linkage between obesity and CRC remains unclear; however, it is believed to be multifactorial in nature. An overview of these mechanisms is shown in Figure 3. Although there are many obesity-linked factors contributing to colorectal carcinogenesis, specific attention has been raised towards the significance of obesity-induced inflammatory dysregulation and dysregulation of insulin and IGF-1 secretion. Figures 4 and 5 have also been used to summarise the current literature of these proposed mechanisms.

The aim of this study was to explore whether recent data and literature confirmed a positive association between obesity and CRC, which was achieved. As mentioned earlier in this review, the current proposed mechanisms between obesity and CRC are multifaceted but can be broadly classified into two categories: Physiological changes brought on by obesity (inflammatory dysregulation, altered gut microbiome, dysregulation of insulin and IGF-1 secretion, T2DM)[8,10], and complications of obesity-linked behaviours (pro-inflammatory diets and sedentary behaviour)[9,12,13]. This review seeks to investigate each of these risk factors and describe the current scientific understanding of how these factors may predispose to CRC (Figure 3).

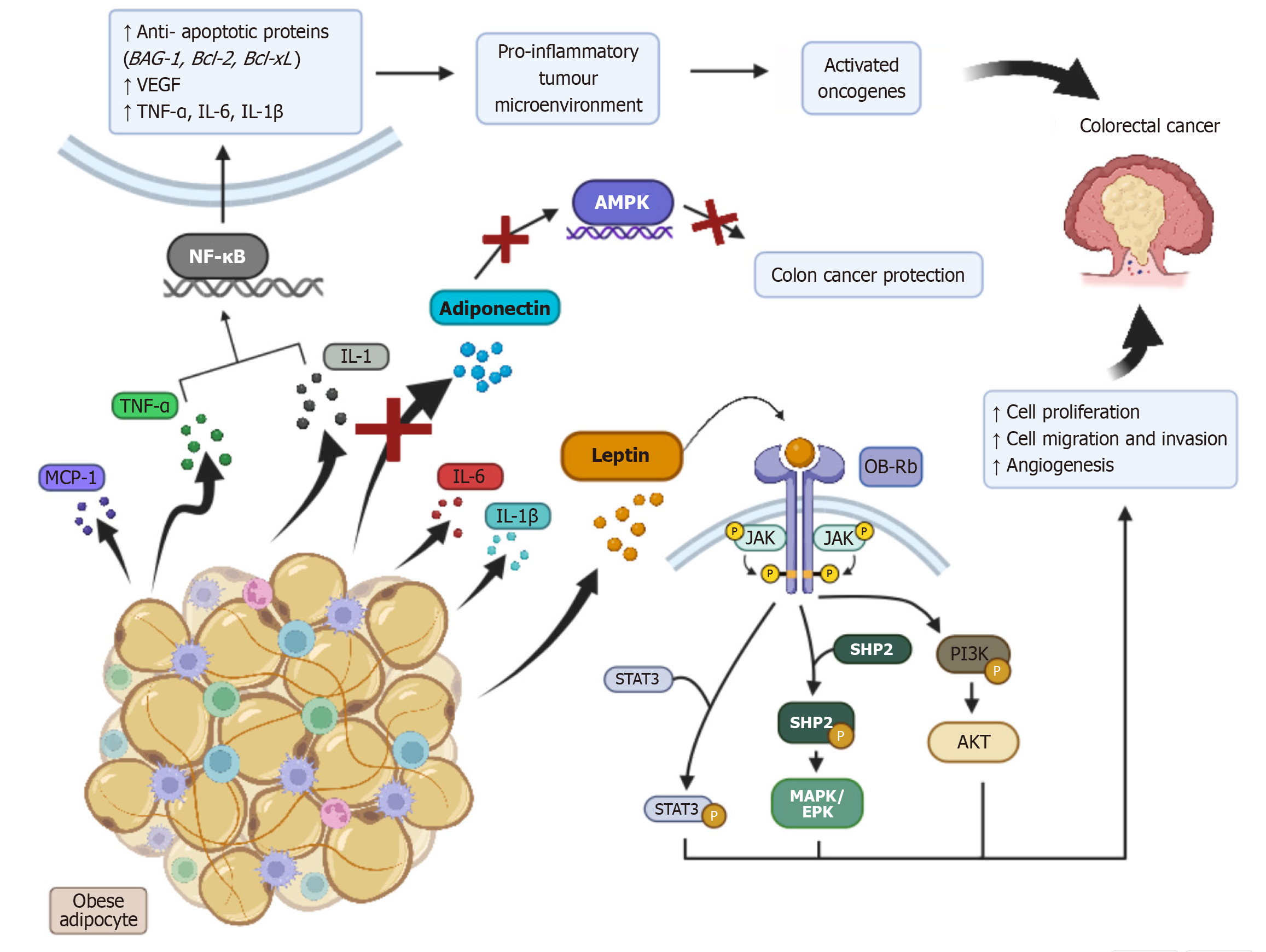

Adipocytes, primarily white adipose tissue (WAT), are heavily involved in the initiation and regulation of the inflammatory process[39]. Obesity induces a phenotypic change to WAT, resulting in adipocyte dysfunction and inflammatory cell infiltration. This may ultimately result in inflammatory dysregulation, inducing the uncontrolled release of potent pro-inflammatory substances, such as inflammatory cytokines [e.g. tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, interleukin-1 beta], and systemic adipokine release (e.g. leptin)[8,40]. Additionally, it also results in downregulation of the release of anti-inflammatory adipokines such as adiponectin[41]. This inflammatory dysregulation induces a chronic low-grade inflammatory state[8,41-43], which via a variety of pathways, NF-κB signalling, leptin hypersecretion and reduced adiponectin levels, can lead to CRC development. A summary of these processes is presented in Figure 4.

The NF-κB signalling pathway, which is made up of five transcription factors that regulate the expression of a number of genes, is activated via cytokines such as IL-1 and TNF-α[42-44]. Via a detailed cascading pathway, activation of NF-κB leads to the formation of a pro-inflammatory tumour microenvironment, the activation of oncogenes and subsequent CRC development[8,42].

Leptin exerts its action via binding to a variety of receptors, including a long isoform obesity receptor (OB-Rb), four short isoforms (OB-Ra, OB-Rc, OB-Rd, OB-Re) and a circulating, soluble form (OB-Re)[44]. Studies reveal that activation of OB-Rb results in the downstream activation of a variety of signalling pathways (JAK/STAT3, PI3K/AKT, MAPK/ERK) that contribute to CRC formation. As such, obesity-induced leptin hypersecretion may substantially increase the risk of CRC. A study by Aleksandrova et al[45] has also proposed that obesity reduces concentrations of the OB-Re receptor. Studies indicate that OB-Re exerts CRC protective effects at non-obese, normal plasma concentrations (RR 0.42, 95%CI: 0.40-0.76), which may provide an additional link between obesity and CRC.

The anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic and anti-atherogenic effects of adiponectin have been well-established in academic literature[46]. These actions are thought to occur from adiponectin activating multiple CRC protective intracellular signalling pathways, the main of which interacts with AMPK[46-48]. Obesity’s downregulation of adiponectin may strip individuals of these CRC protective mechanisms, ultimately increasing their risk of CRC development.

Risk factors for obesity, such as poor diet and low physical activity, as well as obesity in itself, are all features that can alter an individual’s gut microbiome[10]. Patients with CRC possess different compositions of gut microbiota compared to healthy individuals, with Fusobacterium nucleatum, Bacteroides fragilis, Streptococcus gallolyticus and Escherichia coli being some of the most common bacteria related to CRC development[10,49]. Interestingly, Fusobacteria nucleatum is elevated in the saliva and colon of individuals with obesity, and thus may act as a potential link between obesity, gut microbiome changes and CRC. Fusobacterium, as well as other high-risk CRC-inducing microbiotas, are hypothesised to cause chronic inflammation, dysregulation of immune responses and altered dietary metabolism[49]. This ultimately may result in the formation of harmful metabolites (e.g. secondary bile acids, nitrosamines and formate) that, over long periods of exposure, may result in the formation of an oncogenic environment. Despite this, no scientific evidence currently directly links obesity-related gut microbiome changes to CRC[49].

Plasma insulin concentration is often raised in obese individuals, regardless of their diabetic status[8,50]. This is believed to potentially result from dysfunction of normal energy utilisation in obese individuals, as well as more energy and insulin being required to carry out normal metabolic processes compared to those of lean BMI. Insulin is a direct stimulus for IGF-1 production, resulting in a proportional hypersecretion of both IGF-1 and insulin in obese people[8].

IGF-1 receptors have been demonstrated to be present on both healthy colonic epithelium and CRC cells. Upon binding to these receptors, IGF-1 prevents apoptosis of the cell and stimulates cellular proliferation[8]. As CRC development, much like any other cancer, is formed from specific genetic and molecular alterations, an over induced cellular proliferation (a result of obesity-mediated IGF-1 hypersecretion) may increase the risk of these alterations developing within the colonic epithelium, potentially leading to CRC formation.

Additionally, it is proposed that together, insulin and IGF-1 promote rat sarcoma activation, a well-established proto-oncogene related to CRC, responsible for the transformation of colonic adenomas into CRC[8,51]. A summary of these processes is presented in Figure 5.

T2DM is defined as a chronic medical condition describing a dysfunctional secretion of insulin and/or an improper biologic response to insulin, resulting in a consistently hyperglycaemic state[52,53]. Obesity is considered one of the strongest risk factors for T2DM, obese men and women possessing a 4.6 and 3.5 times greater risk of developing T2DM, respectively, compared to non-obese individuals[53]. Siddiqui et al[54] identified a significant link between elevated glycated haemoglobin levels and the early onset of CRC. Additionally, due to mechanisms mentioned previously, the insulin resistance and associated hyperinsulinemia that is synonymous with T2DM greatly increase the risk of CRC[53].

Diet: For many individuals, obesity can result from the adoption of a typical Western diet, which is, characterised by excessive consumption of red meat, processed meat, sugar, saturated fatty acids, cholesterol and trans fats[55,56]. Shivappa et al[11] found that this type of diet contains food of high inflammatory potential, which when taken in excess, can place an individual under a chronic inflammatory state, playing a significant role in colon oncogenesis as discussed earlier in this review. Their study revealed that a high inflammatory potential diet resulted in a 1.40 times increased risk of CRC development (95%CI: 1.25-1.55 RR)[11]. Additionally, overconsumption of red and processed meats increases the concentration of haem iron, N-nitroso compounds, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heterocyclic aromatic amines, which also have oncogenic properties[56]. To reduce CRC risk, individuals should shift away from the Western diet and instead opt for a diet rich in high-fibre foods, fruits, vegetables, dairy products and folate.

Sedentary lifestyle: A sedentary lifestyle, which is often the case for those with obesity, can also be a significant factor for CRC development. A systematic review found that higher levels of sedentary time greatly increased the risk of CRC (RR 1.54, 95%CI: 1.19-1.98) compared to those of an active lifestyle[12]. The mechanisms underpinning this increased risk for CRC development involve sedentary behaviour’s tendency to increase blood glucose, decrease insulin-sensitivity and place an individual under a chronic-inflammatory state by upregulating proinflammatory factors and decreasing anti-inflammatory markers[57,58].

This systematic review examined 15 studies that investigated the link between obesity and CRC, including 13 cohort studies and two case-control studies. Our findings confirm a positive relationship between these two variables, which has reflected the results of previously conducted meta-analyses mentioned earlier in this review[13,14]. From these results, as well as the detailed literature of the biological mechanisms linking obesity and CRC, a definitive association can be made, where obese individuals are more likely to develop CRC. By considering this increased risk of CRC development, we recommend screening for CRC at younger ages for obese individuals to mitigate the potential of early-onset CRC in these groups.

This systematic review also uncovered a potential trend in obesity-induced CRC risk, where a higher severity of obesity induces a greater increased risk for CRC development[25,26,28], which will require further research. Another identified study investigated the association of both general obesity and central obesity with CRC, finding only a positive correlation when both were present in an individual. This reveals another area for further study to investigate if central obesity is an independent risk factor for CRC development, regardless if generalised obesity is present[36].

This review is affected by a few limitations. Much like all meta-analyses, particularly those investigating observational studies, this review may suffer from the presence of publication bias, potentially resulting in overstated HR measures between obesity and CRC. However, the funnel plots for both male and female meta-analyses revealed no gross pub

Additionally, BMI has been described as a non-perfect measure of adiposity, and thus introduces the possibility for stronger associations to be present between CRC and other measurements of overall fatness than what was observed in this meta-analysis[14]. As such, to further investigate the association between obesity and CRC, other measures of adiposity, including waist circumference, waist-hip ratio, or body fat percentage should be used as an alternative or complementary obesity indicator to BMI in future research.

It was also observed that many of the included studies only used a single measure of BMI, which has a tendency to fluctuate over time. As a result, future studies should incorporate multiple repeated measures of an individual’s adiposity to allow for more accurate associations between obesity and CRC to be made.

Despite using a random-effects model to help reduce potential variances in the study designs, they may still have been affected by potential regional and dietary confounding factors, which may explain the moderate heterogeneity of the female meta-analysis (Figure 1B). Lastly, while all studies used in the male and female meta-analyses were weighed according to the amount of precision in their estimated effects, the significant range in sample sizes for the included studies may have potentially been a limitation to this review.

This review explored the association between obesity and CRC, revealing that obesity significantly increases the risk of CRC in both males and females. These findings are supported by established biological mechanisms, including inflammatory dysregulation, insulin resistance, and gut microbiome alterations. Although this review was affected by some limitations, a few strengths were also identified. By including only studies from data registries, the review ensured a standardised case identification process, enhancing the reliability of the findings despite the exclusion of smaller-scale research. Furthermore, the use of large sample sizes for all studies included in this review further enhanced its reliability and reduced the chances of small-study bias. While the review provides strong evidence for this association, the included studies varied in methodology and population characteristics, which may limit the generalisability of the findings.

Given the strong evidence linking obesity to CRC, we recommend commencing screening for CRC at younger ages in obese individuals to mitigate the potential risk of obesity-induced early-onset CRC. Further research is needed to optimise screening guidelines, implications and explore targeted interventions to address this growing public health concern. Additional research should also be conducted to explore genetic predispositions to CRC and its interaction with obesity.

| 1. | Sørensen TIA, Martinez AR, Jørgensen TSH. Epidemiology of Obesity. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2022;274:3-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Boutari C, Mantzoros CS. A 2022 update on the epidemiology of obesity and a call to action: as its twin COVID-19 pandemic appears to be receding, the obesity and dysmetabolism pandemic continues to rage on. Metabolism. 2022;133:155217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 683] [Article Influence: 170.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Koliaki C, Dalamaga M, Liatis S. Update on the Obesity Epidemic: After the Sudden Rise, Is the Upward Trajectory Beginning to Flatten? Curr Obes Rep. 2023;12:514-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lin X, Li H. Obesity: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutics. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:706978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 736] [Article Influence: 147.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hruby A, Hu FB. The Epidemiology of Obesity: A Big Picture. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:673-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1738] [Cited by in RCA: 1807] [Article Influence: 164.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68832] [Article Influence: 13766.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (202)] |

| 7. | Pati S, Irfan W, Jameel A, Ahmed S, Shahid RK. Obesity and Cancer: A Current Overview of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Outcomes, and Management. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 420] [Article Influence: 140.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gribovskaja-Rupp I, Kosinski L, Ludwig KA. Obesity and colorectal cancer. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:229-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Goodwin PJ, Stambolic V. Impact of the obesity epidemic on cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:281-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Spaander MCW, Zauber AG, Syngal S, Blaser MJ, Sung JJ, You YN, Kuipers EJ. Young-onset colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 58.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shivappa N, Godos J, Hébert JR, Wirth MD, Piuri G, Speciani AF, Grosso G. Dietary Inflammatory Index and Colorectal Cancer Risk-A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2017;9:1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Schmid D, Leitzmann MF. Television viewing and time spent sedentary in relation to cancer risk: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ning Y, Wang L, Giovannucci EL. A quantitative analysis of body mass index and colorectal cancer: findings from 56 observational studies. Obes Rev. 2010;11:19-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Moghaddam AA, Woodward M, Huxley R. Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of 31 studies with 70,000 events. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2533-2547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 431] [Cited by in RCA: 461] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1223-1249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6495] [Cited by in RCA: 5853] [Article Influence: 975.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 16. | NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in diabetes prevalence and treatment from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 1108 population-representative studies with 141 million participants. Lancet. 2024;404:2077-2093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 412] [Article Influence: 206.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 52244] [Article Influence: 10448.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 18. | WHO. The Asia-Pacific perspective: redefining obesity and its treatment. 2000. [cited 5 Nov 2024]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/206936. |

| 19. | Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894:i-xii, 1. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta Analysis. 2000. [cited 5 Nov 2024]. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. |

| 21. | Posit team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Boston: Posit Software, PBC. 2024. Available from: http://www.posit.co/. |

| 22. | Viechtbauer W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the meta for Package. J Stat Soft. 2010;36. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7317] [Cited by in RCA: 7427] [Article Influence: 464.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nock NL, Thompson CL, Tucker TC, Berger NA, Li L. Associations between obesity and changes in adult BMI over time and colon cancer risk. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16:1099-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Li H, Boakye D, Chen X, Jansen L, Chang-Claude J, Hoffmeister M, Brenner H. Associations of Body Mass Index at Different Ages With Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:1088-1097.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wang Y, Jacobs EJ, Patel AV, Rodríguez C, McCullough ML, Thun MJ, Calle EE. A prospective study of waist circumference and body mass index in relation to colorectal cancer incidence. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:783-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Song YM, Sung J, Ha M. Obesity and risk of cancer in postmenopausal Korean women. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3395-3402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bassett JK, Severi G, English DR, Baglietto L, Krishnan K, Hopper JL, Giles GG. Body size, weight change, and risk of colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:2978-2986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Oxentenko AS, Bardia A, Vierkant RA, Wang AH, Anderson KE, Campbell PT, Sellers TA, Folsom AR, Cerhan JR, Limburg PJ. Body size and incident colorectal cancer: a prospective study of older women. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2010;3:1608-1620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Li H, Yang G, Xiang YB, Zhang X, Zheng W, Gao YT, Shu XO. Body weight, fat distribution and colorectal cancer risk: a report from cohort studies of 134255 Chinese men and women. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37:783-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Han X, Stevens J, Truesdale KP, Bradshaw PT, Kucharska-Newton A, Prizment AE, Platz EA, Joshu CE. Body mass index at early adulthood, subsequent weight change and cancer incidence and mortality. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:2900-2909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kantor ED, Udumyan R, Signorello LB, Giovannucci EL, Montgomery S, Fall K. Adolescent body mass index and erythrocyte sedimentation rate in relation to colorectal cancer risk. Gut. 2016;65:1289-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hanyuda A, Cao Y, Hamada T, Nowak JA, Qian ZR, Masugi Y, da Silva A, Liu L, Kosumi K, Soong TR, Jhun I, Wu K, Zhang X, Song M, Meyerhardt JA, Chan AT, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci EL, Ogino S, Nishihara R. Body mass index and risk of colorectal carcinoma subtypes classified by tumor differentiation status. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:393-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bao C, Yang R, Pedersen NL, Xu W, Xu H, Song R, Qi X, Xu W. Overweight in midlife and risk of cancer in late life: A nationwide Swedish twin study. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:2128-2134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Wong TS, Chay WY, Tan MH, Chow KY, Lim WY. Reproductive factors, obesity and risk of colorectal cancer in a cohort of Asian women. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;58:33-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Bjørge T, Häggström C, Ghaderi S, Nagel G, Manjer J, Tretli S, Ulmer H, Harlid S, Rosendahl AH, Lang A, Stattin P, Stocks T, Engeland A. BMI and weight changes and risk of obesity-related cancers: a pooled European cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48:1872-1885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Nam GE, Baek SJ, Choi HB, Han K, Kwak JM, Kim J, Kim SH. Association between Abdominal Obesity and Incident Colorectal Cancer: A Nationwide Cohort Study in Korea. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:1368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Seo JY, Jin EH, Chung GE, Kim YS, Bae JH, Yim JY, Han KD, Yang SY. The risk of colorectal cancer according to obesity status at four-year intervals: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Sci Rep. 2023;13:8928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Boon MH, Thomson H. The effect direction plot revisited: Application of the 2019 Cochrane Handbook guidance on alternative synthesis methods. Res Synth Methods. 2021;12:29-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kawai T, Autieri MV, Scalia R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2021;320:C375-C391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 1270] [Article Influence: 211.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kerr J, Anderson C, Lippman SM. Physical activity, sedentary behaviour, diet, and cancer: an update and emerging new evidence. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e457-e471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 441] [Article Influence: 49.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Ahechu P, Zozaya G, Martí P, Hernández-Lizoáin JL, Baixauli J, Unamuno X, Frühbeck G, Catalán V. NLRP3 Inflammasome: A Possible Link Between Obesity-Associated Low-Grade Chronic Inflammation and Colorectal Cancer Development. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Martin M, Sun M, Motolani A, Lu T. The Pivotal Player: Components of NF-κB Pathway as Promising Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:7429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Khanna D, Khanna S, Khanna P, Kahar P, Patel BM. Obesity: A Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation and Its Markers. Cureus. 2022;14:e22711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 49.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Ghasemi A, Saeidi J, Azimi-Nejad M, Hashemy SI. Leptin-induced signaling pathways in cancer cell migration and invasion. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2019;42:243-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Aleksandrova K, Boeing H, Jenab M, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Jansen E, van Duijnhoven FJ, Rinaldi S, Fedirko V, Romieu I, Riboli E, Gunter MJ, Westphal S, Overvad K, Tjønneland A, Halkjær J, Racine A, Boutron-Ruault MC, Clavel-Chapelon F, Kaaks R, Lukanova A, Trichopoulou A, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Mattiello A, Pala V, Palli D, Tumino R, Vineis P, Buckland G, Sánchez MJ, Amiano P, Huerta JM, Barricarte A, Menéndez V, Peeters PH, Söderberg S, Palmqvist R, Allen NE, Crowe FL, Khaw KT, Wareham N, Pischon T. Leptin and soluble leptin receptor in risk of colorectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5328-5337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Achari AE, Jain SK. Adiponectin, a Therapeutic Target for Obesity, Diabetes, and Endothelial Dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 477] [Cited by in RCA: 842] [Article Influence: 93.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 47. | Dalamaga M, Diakopoulos KN, Mantzoros CS. The role of adiponectin in cancer: a review of current evidence. Endocr Rev. 2012;33:547-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 428] [Cited by in RCA: 495] [Article Influence: 35.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Keerthana CK, Rayginia TP, Shifana SC, Anto NP, Kalimuthu K, Isakov N, Anto RJ. The role of AMPK in cancer metabolism and its impact on the immunomodulation of the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1114582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Rebersek M. Gut microbiome and its role in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 47.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Sikalidis AK, Varamini B. Roles of hormones and signaling molecules in describing the relationship between obesity and colon cancer. Pathol Oncol Res. 2011;17:785-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Rasouli N, Kern PA. Adipocytokines and the metabolic complications of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:S64-S73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 519] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Galicia-Garcia U, Benito-Vicente A, Jebari S, Larrea-Sebal A, Siddiqi H, Uribe KB, Ostolaza H, Martín C. Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:6275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 1676] [Article Influence: 279.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Chandrasekaran P, Weiskirchen R. The Role of Obesity in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus-An Overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:1882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 116.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Siddiqui AA, Spechler SJ, Huerta S, Dredar S, Little BB, Cryer B. Elevated HbA1c is an independent predictor of aggressive clinical behavior in patients with colorectal cancer: a case-control study. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2486-2494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Clemente-Suárez VJ, Beltrán-Velasco AI, Redondo-Flórez L, Martín-Rodríguez A, Tornero-Aguilera JF. Global Impacts of Western Diet and Its Effects on Metabolism and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2023;15:2749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 421] [Article Influence: 140.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 56. | Thanikachalam K, Khan G. Colorectal Cancer and Nutrition. Nutrients. 2019;11:164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 521] [Article Influence: 74.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Namasivayam V, Lim S. Recent advances in the link between physical activity, sedentary behavior, physical fitness, and colorectal cancer. F1000Res. 2017;6:199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Cong YJ, Gan Y, Sun HL, Deng J, Cao SY, Xu X, Lu ZX. Association of sedentary behaviour with colon and rectal cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:817-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. Available from: http://www.handbook.cochrane.org. |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/