Published online Dec 24, 2025. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v16.i12.112140

Revised: August 20, 2025

Accepted: November 7, 2025

Published online: December 24, 2025

Processing time: 157 Days and 23.6 Hours

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene fusion is a molecular subtype of non-small cell lung cancer, representing 4%-6% of lung adenocarcinomas. Axillary lymph node (ALN) metastasis from lung cancer is rare, and massive bleeding from such lesions is an even more unusual and life-threatening complication. This case demonstrates how localized radiotherapy can be used as an effective hemostatic and tumor-controlling measure when conventional interventions fail.

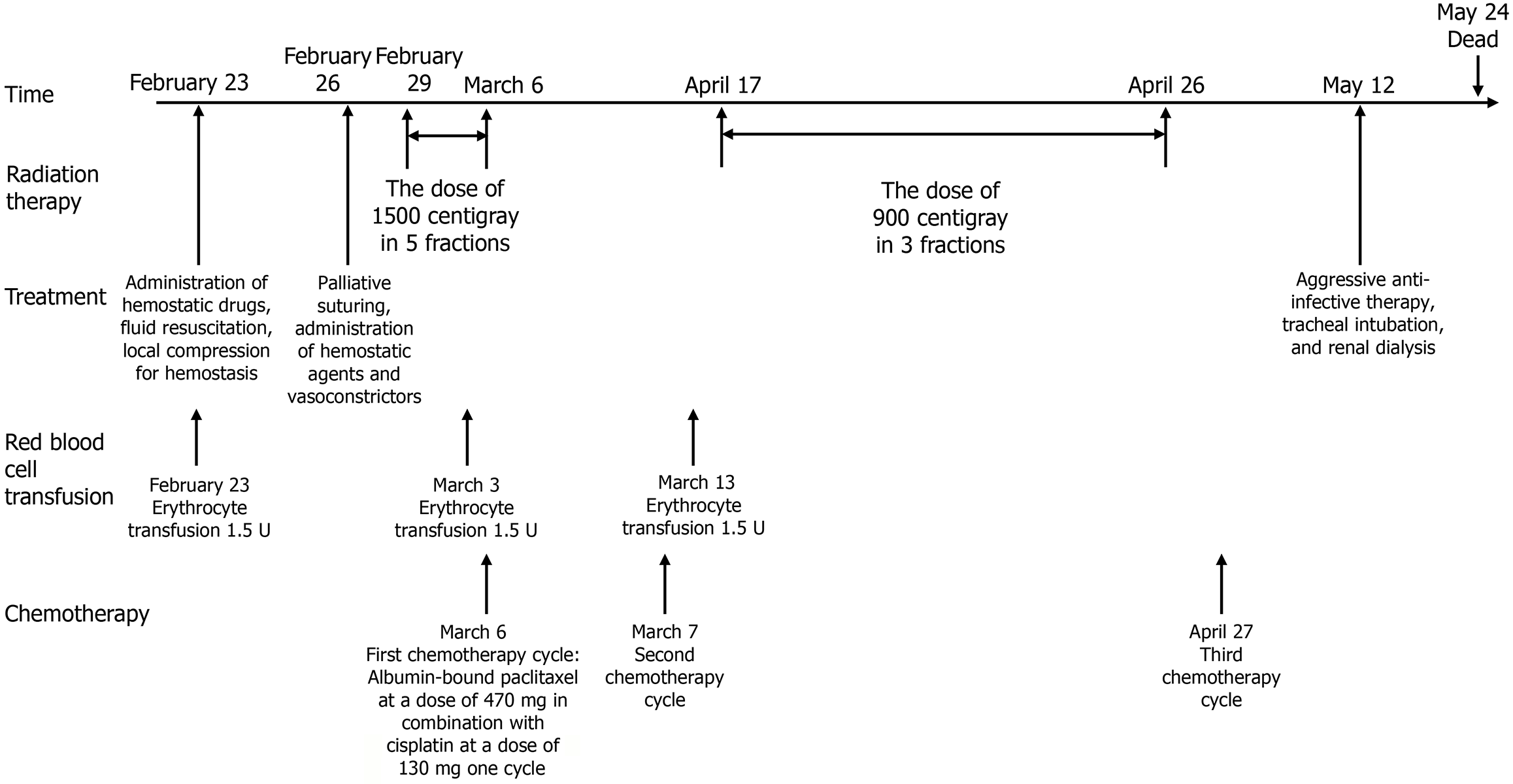

A 48-year-old male presented in October 2019 with ALK-positive lung adenocarcinoma and multiple metastases. He received multiple lines of ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, whole-brain radiotherapy, stereotactic radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted agents over 4 years and 7 months. In February 2024, rapid enlargement and rupture of a left ALN metastasis caused massive bleeding. Interventional and surgical hemostasis were not feasible. Localized radiotherapy was initiated at 15 Gray in 5 fractions, later increased to a total of 39 Gray in 13 fractions, resulting in rapid bleeding control and partial tumor response. The patient subsequently received chemotherapy, and the axillary lesion healed without recurrent bleeding. However, three months later, he developed severe pneumonia with mixed bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal infections and died despite intensive care.

Radiotherapy can effectively control bleeding and achieve local tumor control in ALK-positive lung cancer with ruptured ALN metastasis when other treatments are ineffective.

Core Tip: This case describes a patient with anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive lung adenocarcinoma who developed massive bleeding from an axillary lymph node metastasis after resistance to multiple lines of targeted therapy. Localized radiotherapy achieved rapid hemostasis and effective local control when other interventions failed. The report discusses bleeding mechanisms, preventive strategies during radiotherapy, and the importance of multidisciplinary management. These findings provide practical guidance for treating rare but life-threatening complications in advanced lung cancer.

- Citation: Li ZM, Wang YC, Wang KY, Xie NJ, Zhou J, Chang XN, Chen Q, Wang G, Zhang S, Zhou R. Radiotherapy for large ruptured hemorrhagic axillary lymph node metastasis from anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive lung adenocarcinoma: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Oncol 2025; 16(12): 112140

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v16/i12/112140.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v16.i12.112140

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene fusion is a molecular subtype of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that represents 4%-6% of lung adenocarcinomas[1]. This chromosomal rearrangement affects the ALK gene on its respective chromosome, leading to the aberrant expression of the tyrosine kinase portion of ALK and its constant activation. Cancers that are positive for ALK rely on this abnormality and are generally responsive to drugs that inhibit ALK, known as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs)[2]. As of now, the United States Food and Drug Administration has approved 5 different ALK-TKIs for the treatment of ALK-positive (ALK+) NSCLC, China Food and Drug Administration and more are in the process of being developed.

ALK+ patients had a poor prognosis before the advent of targeted drugs due to its potent oncogenic properties[3]. However, with the successful development of first, second, and third-generation ALK-TKIs, there has been a significant increase in the survival time of ALK+ patients. ALK-TKIs are now established as the standard first-line therapy for ALK+ NSCLC. Notably, among all the treatment data published for advanced lung cancer involving ALK-TKIs, lorlatinib seems to demonstrate superior efficacy. The most recent 5-year comparative data released in 2024 indicate that the median progression-free survival (PFS) for lorlatinib has not yet been reached (95% confidence interval: 64.3 months to not reported), with a 5-year PFS rate of 60%[1]. Despite the advancements in treatment efficacy with newer medications, TKI resistance continues to be a substantial challenge for both medical oncologists and patients.

In lung cancer, metastases to the axillary lymph nodes (ALNs) are uncommon (0.75%), and based on the 9th edition staging system, they are designated as M1 disease[4]. Although lung adenocarcinoma is the type of lung cancer most likely to metastasize to the ALN, and ALK+ lung cancer patients are characterized by early widespread metastasis[5], a massive ALN with hemorrhage is still a rare complication of lung cancer. The management of hemorrhage from metastatic lung cancer lesions is governed by the principle of treating the primary malignancy. In instances where bleeding poses a life-threatening risk, symptomatic care including red blood cell transfusions may be warranted. Prevailing medical opinion advocates that aggressive treatment of metastatic sites is a crucial intervention to extend the survival of patients with advanced pulmonary carcinoma. Should systemic disease manifestations be effectively managed, and the presence of bleeding is confined to localized vascular invasion or tumoral rupture by metastatic foci, consideration may be given to localized therapeutic approaches, such as interventional embolization procedures, focal surgical excision, and radiotherapeutic interventions. This report discusses a case of advanced ALK+ lung adenocarcinoma with rapid ALN progression and bleeding. Localized radiotherapy was employed successfully after other treatments failed, providing valuable insights into managing similar complications in clinical practice.

A 48-year-old male presented to the Respiratory Department in October 2019 with chest tightness and coughing.

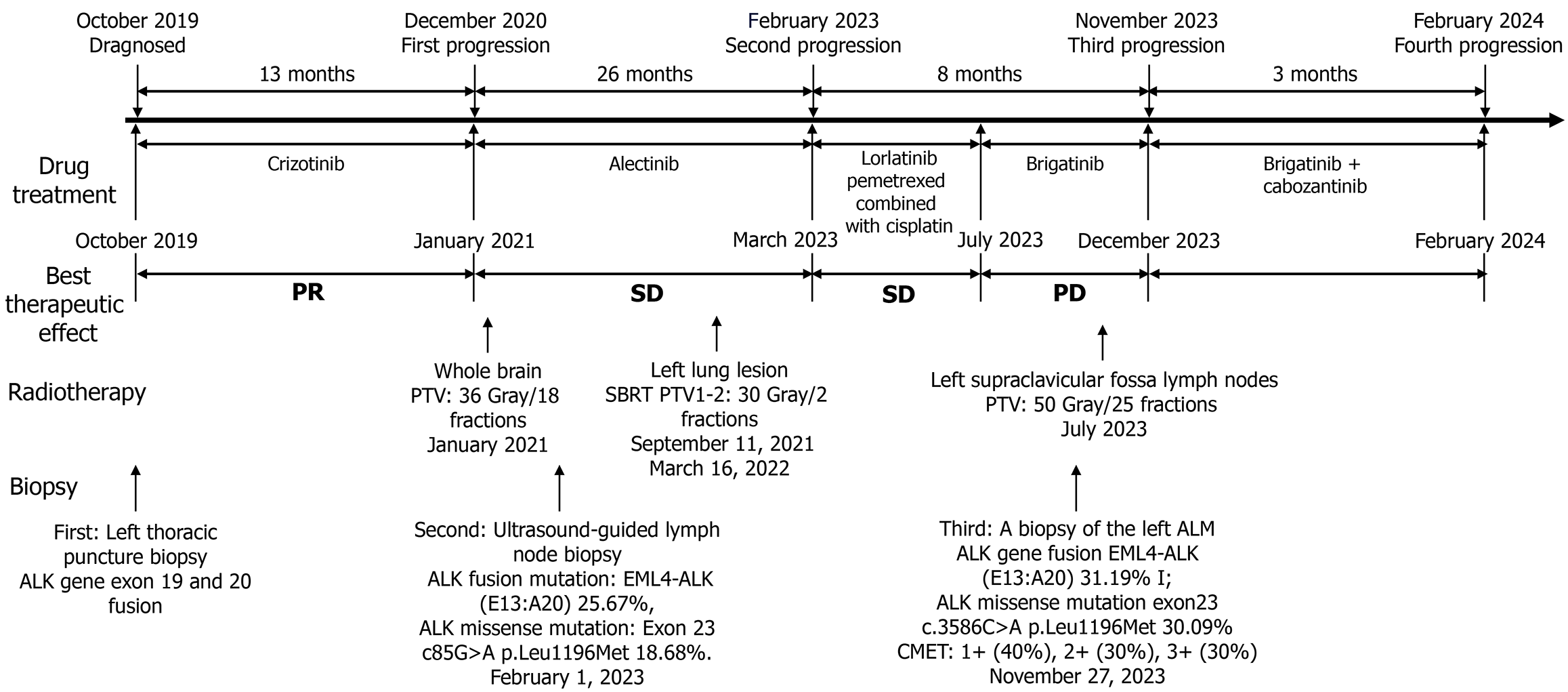

A left thoracic puncture biopsy diagnosed him with left lung adenocarcinoma (Supplementary Figure 1), staged as cTN3M1c (American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th). At diagnosis, he had multiple metastases including those in the left lung, left pleura, bilateral supraclavicular areas, mediastinum, left hilar lymph nodes, and multiple bone metastases. The initial tissue polymerase chain reaction test indicated an ALK gene exon 19 fusions and 20 fusions (epidermal growth factor receptor, receptor tyrosine kinase ROS proto-oncogene 1, Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog, B-RAF proto-oncogene serine/threonine kinase, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, RET proto-oncogene, MET14 skipping were all negative). Treatment with crizotinib was commenced in October 2019 and continued until December 2020 [best therapeutic effect evaluated as partial response (PR)]. In December 2020, the patient visited the Oncology Department for dizziness, and a brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed multiple intracranial metastatic tumors (multiple metastases in both cerebral hemispheres, pons, and cerebellum), while extracranial lesions continued to show a PR, with PFS1 = 13 months. Whole brain radiotherapy was initiated in January 2021 at a total dose of planning target volume (PTV): 36 Gray/18 fractions, and treatment was switched to alectinib in January 2021. In August 2021, a follow-up lung computed tomography (CT) scan showed an increase in the lesion in the upper lobe of the left lung, evaluated as stable disease (SD), and Cyberknife (stereotactic body radiotherapy) treatment for the lesion in the upper lobe of the left lung was performed on September 11, 2021, dose total (Dt) PTV1: 30 Gray/2 fractions. Alectinib was continued orally until March 2022, when a CT scan evaluation showed SD. On March 16, 2022, another Cyberknife treatment for a different lesion in the left lung was administered, Dt PTV2: 30 Gray/2 fractions. Alectinib treatment was continued, and subsequent evaluations showed slow progression until February 2023 (PFS2 = 26 months). On February 1, 2023, due to progression of the left cervical lymph node, an ultrasound-guided lymph node biopsy was performed, pathology showing: Metastatic lung adenocarcinoma [cytokeratin 7 (+), thyroid transcription factor-1 (+), Napsin A (+), p40 (+)]. Another next-generation sequencing (NGS) test showed an ALK fusion mutation: Echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 (EML4)-ALK (E13:A20) 25.67%, and an ALK missense mutation: Exon 23 c85G>A p.Leu1196Met (p.L1196M) 18.68%. In March 2023, treatment was switched to lorlatinib, and by June 2023, a CT scan evaluation showed enlarged SD (enlargement and fusion of left supraclavicular lymph nodes, invasion of adjacent shoulder muscles and scapula). On June 15, 2023, the first cycle of pemetrexed combined with cisplatin chemotherapy was started. After one cycle of chemotherapy, the lesions showed SD, thus continuation of chemotherapy was advised, but the patient refused due to poor tolerance. In July 2023, treatment was changed to brigatinib, along with radiotherapy for the left supraclavicular fossa lymph nodes, Dt PTV: 50 Gray/25 fractions. In November 2023, a CT scan showed SD of the left supraclavicular fossa lymph nodes, with an increase in the left axillary lymph node metastasis (ALM), the disease evaluated as progressive disease (PFS3 = 8 months). On November 27, 2023, a biopsy of the left ALM showed: Lung-derived poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma [thyroid transcription factor-1 (partially +), p40 (-), ALK (D5F3-ventana +), cellular mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor (CMET): 1+ (40%), 2+ (30%), 3+ (30%)]. NGS: ALK gene fusion EML4-ALK (EML4 exon 13:ALK exon 20) 31.19% I; ALK missense mutation exon 23 c.3586C>A p.Leu1196Met 30.09%; tumor protein 53 nonsense mutation exon 8 c.916C>T p.Arg306 11.22%; RET proto-oncogene missense mutation exon 6 c.1250G>A p.Arg417His 50.70%; receptor tyrosine kinase ROS proto-oncogene 1 missense mutation exon 9 c.931G>C p.Asp311His 4.13%; ataxia-telangiectasia mutated copy number amplification 11q22.3 CN: 4.5. In December 2023, the patient began combination therapy with cabozantinib (CMET TKI), continuing until February 2024 (PFS4 = 3 months). In February 2024, the patient was readmitted for significant enlargement and bleeding of the left ALN. The entire treatment process for this patient is shown in Figure 1.

No significant history of chronic diseases prior to the lung adenocarcinoma diagnosis.

No family history of malignancy or hereditary disease was reported.

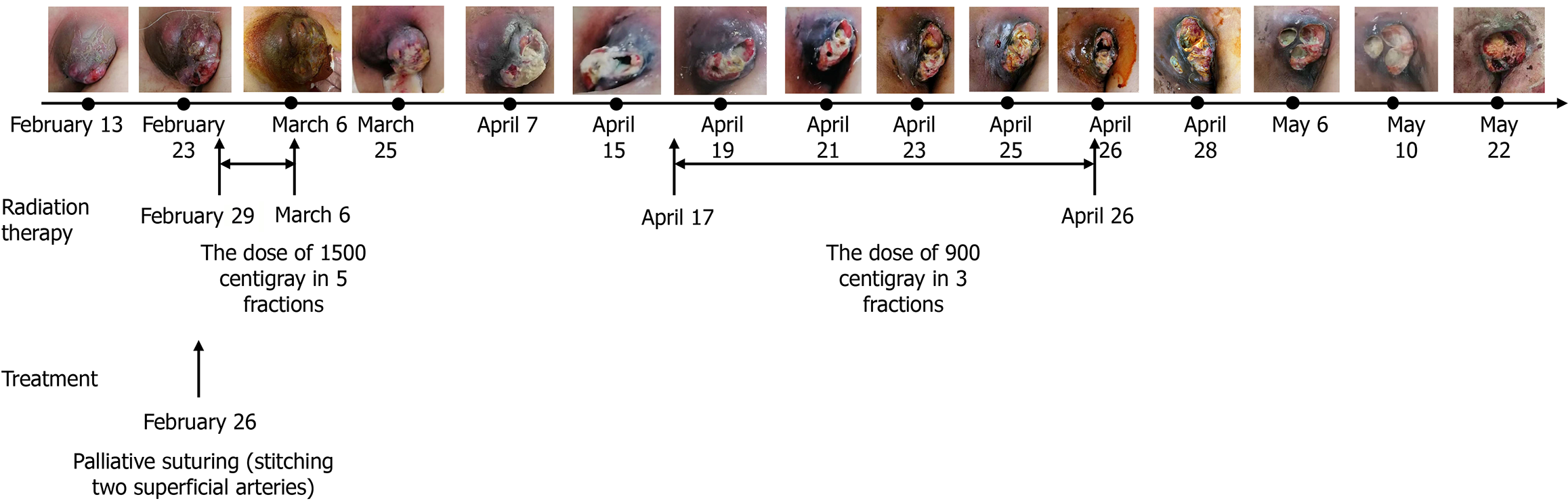

On admission for preparation for ALM radiotherapy, the patient presented with an ulcerated left axillary mass, skin infiltration, and visibly dilated subcutaneous vessels. Intermittent active bleeding was observed from superficial arterial and venous branches. The patient appeared pale but was hemodynamically stable at rest.

On February 21, 2024, complete blood count revealed hemoglobin 97 g/L, red blood cells count 4.13 × 1012/L, mean corpuscular volume: 81.8 fL, mean corpuscular hemoglobin 23 pg, and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration 286 g/L. White blood cells was 6.33 × 109/L with neutrophils 4.67 × 109/L. C-reactive protein was markedly elevated at 117.32 mg/L. Platelets count was 551 × 109/L. Coagulation profile showed activated partial thromboplastin time 37.1 seconds, prothrombin time 13.9 seconds, international normalized ratio 1.07, fibrinogen 8.24 g/L, thrombin time 23.3 seconds, and prothrombin time activity 89%. Liver and renal function tests, as well as electrolyte levels, were within normal ranges. Tumor markers were elevated: Carcinoembryonic antigen 52.21 μg/L, carbohydrate antigen 125270.1 U/mL, and carbohydrate antigen 153125.5 U/mL. Microbial culture and identification of the ulcerated areas on the surface of the lymph nodes indicate infection with Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis.

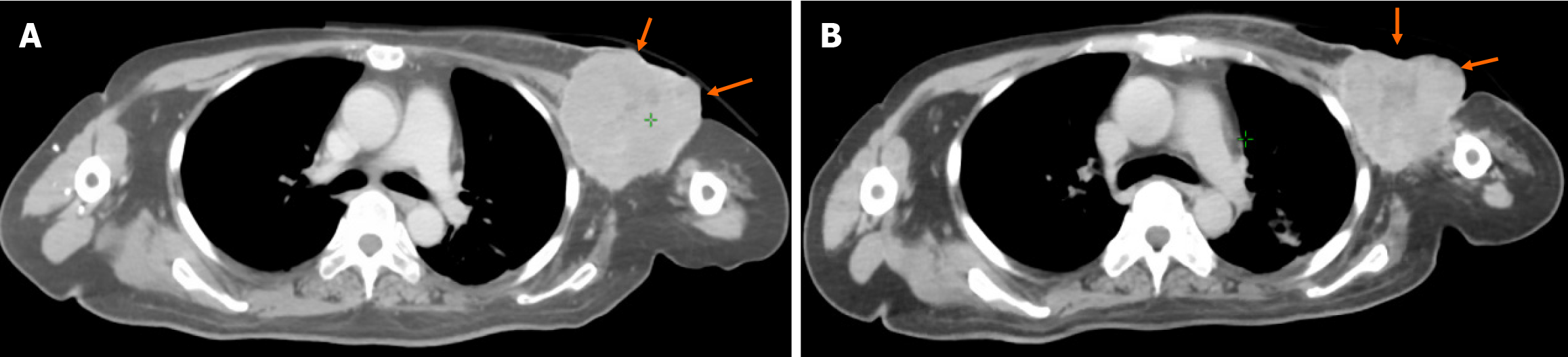

An enhanced CT scan performed on February 21, 2024, showed a large left ALN with a maximum cross-sectional dia

Consultations with interventional radiology and surgical teams concluded that surgical or embolization procedures were not feasible due to superficial vessel rupture and suspected chest wall invasion.

ALK+ lung adenocarcinoma with ALN metastasis, complicated by massive bleeding and secondary infection.

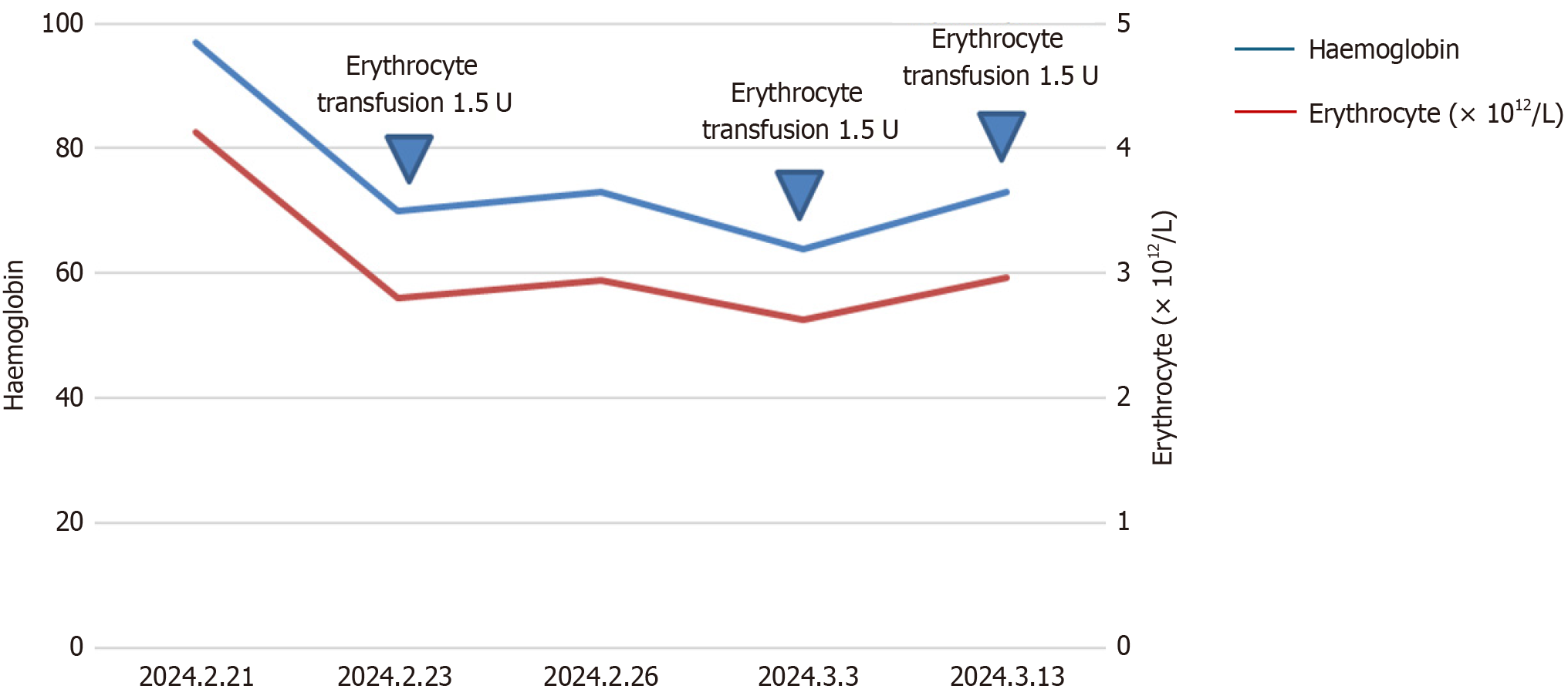

In early February 2024, the patient began experiencing rupture and bleeding of the ALNs, managing hemostasis at home. Upon admission to the hospital on February 21, the patient was diagnosed with moderate anemia. On the night of February 23, the patient suffered a major hemorrhage from ALM, with an estimated blood loss of about 1000 mL. At that time, the patient’s blood pressure was 99/60 mmHg, heart rate 110 bpm, oxygen saturation 91%, and the patient was lethargic. Urgent blood tests showed: Red blood cell count: 3.3 × 1012/L, hemoglobin: 83 g/L, mean corpuscular volume: 81.7 fL, mean corpuscular hemoglobin: 25.1 pg, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration: 308 g/L, platelets: 620 ×

On May 12, 2024, the patient was admitted to the hospital again due to shortness of breath, and was transferred to the intensive care unit, where an emergency CT scan and bronchoalveolar lavage were performed. The results from targeted sequencing captured by a bioprobe indicated infections with Enterococcus faecium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Cladosporium cladosporioides (Supplementary Table 1). The patient was diagnosed with severe pneumonia, renal failure, and sepsis. Treatment included aggressive anti-infective therapy, tracheal intubation, and renal dialysis. Subsequent analysis of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid confirmed the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA, leading to a transfer to a tuberculosis hospital for treatment. The patient ultimately passed away on May 24, 2024, outside the hospital. The patient’s overall survival was 4 years and 7 months, with an intracranial lesion post-radiotherapy duration of response of 42 months, and an ALN post-radiotherapy duration of response of 3 months (Figure 5).

This study reports a rare and clinically informative case of advanced lung adenocarcinoma initially diagnosed with EML4-ALK fusion, in which localized radiotherapy was used to effectively manage a bleeding ALN metastasis after the failure of multiple systemic therapies. The favorable hemostatic and tumor-controlling outcomes observed in this case underscore the potential of radiotherapy as a valuable therapeutic option in select clinical scenarios, where conventional interventions are insufficient.

ALK is a tyrosine kinase receptor that was first implicated in NSCLC in 2007 following the identification of the EML4-ALK fusion gene, which results from a chromosomal inversion[6]. This fusion leads to constitutive activation of the ALK kinase domain and oncogenic transformation. Prior to the era of targeted therapy, ALK+ NSCLC was treated with platinum-based chemotherapy, which yielded modest outcomes - objective response rates of approximately 45% and median PFS of around 7 months[3].

The advent of ALK-TKI crizotinib markedly improved the prognosis, increasing the 4-year survival rate to 56.6% and extending the median survival time to 47.5 months[7]. Second-generation TKIs such as alectinib, ceritinib, and brigatinib further enhanced PFS and overall survival[8-10]. Notably, the phase III ALEX trial demonstrated a median PFS of 34.8 months with alectinib in the first-line setting[11], with even more favorable results observed in Asian cohorts (a median PFS reaching 41.6 months and a 5-year survival rate of 66.4%)[12]. Recently, the phase III crown study established lorlatinib as a new standard of care, reporting a 5-year PFS rate of over 60%, positioning the management of ALK+ NSCLC closer to a chronic disease paradigm[1].

However, resistance to TKIs remains inevitable. As survival times have lengthened, so too has the complexity of resistance mechanisms. With the increasing use of NGS, resistance patterns are now better classified into on-target (i.e., ALK-dependent) and off-target (ALK-independent) categories[13,14]. Crizotinib resistance is often due to pharmacokinetic issues, ALK point mutations (such as L1196M, G1269A, F1174 L), or bypass pathway activation[15]. Second-generation inhibitors can overcome many of these mutations, but solvent-front mutations like G1202R confer cross-resistance to both first-generation and second-generation TKIs[15]. Third-generation TKIs like lorlatinib were developed to overcome such mutations, yet resistance still emerges, often involving compound mutations or off-target mechanisms[16]. In this case, the patient harbored an ALK p.L1196M mutation and subsequently developed additional mutations (e.g., CMET amplification), illustrating dynamic clonal evolution under treatment pressure. Although temporary disease control was achieved with CMET inhibition, response duration was short, and subsequent treatment with chemotherapy proved more effective. This trajectory highlights a concerning trend: Multi-line TKI-treated tumors may evolve toward greater heterogeneity, aggressiveness, and treatment refractoriness.

For patients with advanced ALK+ NSCLC who are ineligible for surgery, radiotherapy plays a complementary role. Adjuvant alectinib has shown benefit in prolonging disease-free survival in resected cases, but most patients present with widespread metastases at diagnosis[17]. In cases of oligoprogression, combining radiotherapy with ongoing systemic therapy can offer prolonged disease control[18]. Preclinical data suggest that irradiation can sensitize ALK+ tumor cells to TKI treatment[19], though the inverse does not appear to be true[20]. In resistant cases, stereotactic body radiotherapy can effectively manage progressing lesions and maintain systemic disease control[21]. Furthermore, radiotherapy remains a cornerstone in the management of symptomatic metastases, especially those involving the brain[22]. In this patient, radiotherapy was used at three different disease stages and consistently yielded local control. This reinforces its utility not only as a cytoreductive modality but also as a symptom-directed, life-extending intervention, particularly when integrated within a multidisciplinary approach for managing TKI-resistant, high-burden disease.

ALN metastasis from lung cancer is a rare occurrence. Patients with ALN metastasis typically have a poor prognosis, and retrospective studies report a median survival time of approximately 7 months at the time of initial diagnosis[4]. While tumor progression is often the direct cause of mortality, in rare cases, metastatic lymph nodes may rupture and bleed, leading to acute, life-threatening complications. Tumor-associated hemorrhage can be classified into two types: One is bleeding from the tumor itself, due to the rich vasculature within the tumor tissue, which is mostly composed of neovascularization with incomplete endothelial connections, leading to bleeding during rapid proliferation; the other type is bleeding caused by the highly invasive and aggressive biological behavior of the tumor, resulting in the rupture of nearby blood vessels[23].

Effective anti-tumor treatment is the basic principle for managing tumor-related bleeding, but in cases where treatment is ineffective or acute life-threatening bleeding events occur, surgical intervention, endoscopic hemostasis, or tran

Radiotherapy has been proven effective in controlling tumor-related bleeding in various malignancies, including gastrointestinal bleeding[25], hemoptysis[26-28], hematuria[29], and vaginal bleeding[30]. The onset of hemostasis is often rapid, with some reports noting clinical improvement within 24-48 hours after initiation. In this case, treatment regimens include a single dose of 8-10 Gray, a moderate course of 4-8 Gray/3-5 fractions, or an extended course of 30-45 Gray/10-15 fractions. While no specific regimen has been definitively identified as most effective, shorter courses have been associated with fewer side effects[31]. Given that the patient had previously undergone radiotherapy for ipsilateral supraclavicular lymph nodes and considering the dose constraints for the brachial plexus and spinal cord, a total dose of 24 Gray/8 fractions was administered gradually. After the second treatment, there was a significant reduction in ALN bleeding, and hemoglobin levels increased progressively, with subsequent lesion response assessed as PR. Consequently, radiotherapy significantly contributed to hemostasis and tumor control for this patient, affording opportunities for further treatment and extending survival time.

Importantly, while bleeding was successfully controlled, the patient eventually died from severe infection. This outcome underscores the critical need to recognize infection as a major and often underestimated threat in the ma

Another area of growing interest is the integration of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) into the treatment of ALK+ lung adenocarcinoma. Although TCM was not employed in this case, evidence suggests that it may contribute to improving patient outcomes by modulating immunity, reducing treatment-related toxicities, and enhancing quality of life. Recent studies have also highlighted the role of TCM in reducing complications such as infection and bleeding[32,33]. Individualized TCM protocols may be especially valuable in patients undergoing multimodal therapy. Future studies should investigate the incorporation of TCM into standard treatment regimens, particularly in the context of resistance and symptom management.

Finally, the issue of preventive strategies for tumor-associated bleeding deserves further attention. Early identification of high-risk lesions, such as tumors with skin involvement or proximity to major vessels, may allow for timely prophylactic intervention. Options could include low-dose radiotherapy, the use of anti-angiogenic agents, or earlier surgical debridement before vascular rupture. While this case required emergent intervention due to rapid tumor progression, it highlights the necessity of proactive multidisciplinary planning in similar scenarios.

In summary, this case offers a detailed clinical perspective on managing advanced ALK+ NSCLC complicated by rare but severe events such as massive ALN bleeding and fatal infection. Radiotherapy provided effective local control when other hemostatic measures failed. The outcome highlights the need for vigilant infection prevention in advanced disease, as well as the importance of multidisciplinary coordination. Future research should focus on refining integrated treatment strategies that combine systemic therapy, targeted radiotherapy, and optimized supportive care to address both oncologic control and complication management.

Radiotherapy can serve as an effective hemostatic and local control measure for massive bleeding from ALN metastases in ALK+ NSCLC when conventional interventions fail. This case underscores the importance of early risk identification, multidisciplinary management, and proactive infection prevention to improve patient outcomes. Integrated strategies combining systemic therapy, targeted radiotherapy, and comprehensive supportive care may further optimize survival and quality of life in this patient population.

| 1. | Solomon BJ, Liu G, Felip E, Mok TSK, Soo RA, Mazieres J, Shaw AT, de Marinis F, Goto Y, Wu YL, Kim DW, Martini JF, Messina R, Paolini J, Polli A, Thomaidou D, Toffalorio F, Bauer TM. Lorlatinib Versus Crizotinib in Patients With Advanced ALK-Positive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Outcomes From the Phase III CROWN Study. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:3400-3409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 110.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Golding B, Luu A, Jones R, Viloria-Petit AM. The function and therapeutic targeting of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Mol Cancer. 2018;17:52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, Mekhail T, Felip E, Cappuzzo F, Paolini J, Usari T, Iyer S, Reisman A, Wilner KD, Tursi J, Blackhall F; PROFILE 1014 Investigators. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2167-2177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2160] [Cited by in RCA: 2543] [Article Influence: 211.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Satoh H, Ishikawa H, Kagohashi K, Kurishima K, Sekizawa K. Axillary lymph node metastasis in lung cancer. Med Oncol. 2009;26:147-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Üstün F, Tokuc B, Tastekin E, Durmuş Altun G. Tumor characteristics of lung cancer in predicting axillary lymph node metastases. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol (Engl Ed). 2019;38:80-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, Takada S, Yamashita Y, Ishikawa S, Fujiwara S, Watanabe H, Kurashina K, Hatanaka H, Bando M, Ohno S, Ishikawa Y, Aburatani H, Niki T, Sohara Y, Sugiyama Y, Mano H. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448:561-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3816] [Cited by in RCA: 4175] [Article Influence: 219.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Solomon BJ, Kim DW, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, Mekhail T, Felip E, Cappuzzo F, Paolini J, Usari T, Tang Y, Wilner KD, Blackhall F, Mok TS. Final Overall Survival Analysis From a Study Comparing First-Line Crizotinib Versus Chemotherapy in ALK-Mutation-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2251-2258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 307] [Article Influence: 38.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Gadgeel S, Ahn JS, Kim DW, Ou SI, Pérol M, Dziadziuszko R, Rosell R, Zeaiter A, Mitry E, Golding S, Balas B, Noe J, Morcos PN, Mok T; ALEX Trial Investigators. Alectinib versus Crizotinib in Untreated ALK-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:829-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1385] [Cited by in RCA: 1865] [Article Influence: 207.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Soria JC, Tan DSW, Chiari R, Wu YL, Paz-Ares L, Wolf J, Geater SL, Orlov S, Cortinovis D, Yu CJ, Hochmair M, Cortot AB, Tsai CM, Moro-Sibilot D, Campelo RG, McCulloch T, Sen P, Dugan M, Pantano S, Branle F, Massacesi C, de Castro G Jr. First-line ceritinib versus platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer (ASCEND-4): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2017;389:917-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 692] [Cited by in RCA: 885] [Article Influence: 98.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Camidge DR, Kim HR, Ahn MJ, Yang JCH, Han JY, Hochmair MJ, Lee KH, Delmonte A, Garcia Campelo MR, Kim DW, Griesinger F, Felip E, Califano R, Spira AI, Gettinger SN, Tiseo M, Lin HM, Liu Y, Vranceanu F, Niu H, Zhang P, Popat S. Brigatinib Versus Crizotinib in ALK Inhibitor-Naive Advanced ALK-Positive NSCLC: Final Results of Phase 3 ALTA-1L Trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16:2091-2108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 51.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mok T, Camidge DR, Gadgeel SM, Rosell R, Dziadziuszko R, Kim DW, Pérol M, Ou SI, Ahn JS, Shaw AT, Bordogna W, Smoljanović V, Hilton M, Ruf T, Noé J, Peters S. Updated overall survival and final progression-free survival data for patients with treatment-naive advanced ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer in the ALEX study. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1056-1064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 462] [Article Influence: 77.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhou C, Kim SW, Reungwetwattana T, Zhou J, Zhang Y, He J, Yang JJ, Cheng Y, Lee SH, Bu L, Xu T, Yang L, Wang C, Liu T, Morcos PN, Lu Y, Zhang L. Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated Asian patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (ALESIA): a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:437-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 29.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Elshatlawy M, Sampson J, Clarke K, Bayliss R. EML4-ALK biology and drug resistance in non-small cell lung cancer: a new phase of discoveries. Mol Oncol. 2023;17:950-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mizuta H, Okada K, Araki M, Adachi J, Takemoto A, Kutkowska J, Maruyama K, Yanagitani N, Oh-Hara T, Watanabe K, Tamai K, Friboulet L, Katayama K, Ma B, Sasakura Y, Sagae Y, Kukimoto-Niino M, Shirouzu M, Takagi S, Simizu S, Nishio M, Okuno Y, Fujita N, Katayama R. Gilteritinib overcomes lorlatinib resistance in ALK-rearranged cancer. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tabbò F, Reale ML, Bironzo P, Scagliotti GV. Resistance to anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibitors: knowing the enemy is half the battle won. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2020;9:2545-2556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yoda S, Lin JJ, Lawrence MS, Burke BJ, Friboulet L, Langenbucher A, Dardaei L, Prutisto-Chang K, Dagogo-Jack I, Timofeevski S, Hubbeling H, Gainor JF, Ferris LA, Riley AK, Kattermann KE, Timonina D, Heist RS, Iafrate AJ, Benes CH, Lennerz JK, Mino-Kenudson M, Engelman JA, Johnson TW, Hata AN, Shaw AT. Sequential ALK Inhibitors Can Select for Lorlatinib-Resistant Compound ALK Mutations in ALK-Positive Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:714-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wu YL, Dziadziuszko R, Ahn JS, Barlesi F, Nishio M, Lee DH, Lee JS, Zhong W, Horinouchi H, Mao W, Hochmair M, de Marinis F, Migliorino MR, Bondarenko I, Lu S, Wang Q, Ochi Lohmann T, Xu T, Cardona A, Ruf T, Noe J, Solomon BJ; ALINA Investigators. Alectinib in Resected ALK-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:1265-1276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 127.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kroeze SGC, Pavic M, Stellamans K, Lievens Y, Becherini C, Scorsetti M, Alongi F, Ricardi U, Jereczek-Fossa BA, Westhoff P, But-Hadzic J, Widder J, Geets X, Bral S, Lambrecht M, Billiet C, Sirak I, Ramella S, Giovanni Battista I, Benavente S, Zapatero A, Romero F, Zilli T, Khanfir K, Hemmatazad H, de Bari B, Klass DN, Adnan S, Peulen H, Salinas Ramos J, Strijbos M, Popat S, Ost P, Guckenberger M. Metastases-directed stereotactic body radiotherapy in combination with targeted therapy or immunotherapy: systematic review and consensus recommendations by the EORTC-ESTRO OligoCare consortium. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24:e121-e132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 43.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dai Y, Wei Q, Schwager C, Hanne J, Zhou C, Herfarth K, Rieken S, Lipson KE, Debus J, Abdollahi A. Oncogene addiction and radiation oncology: effect of radiotherapy with photons and carbon ions in ALK-EML4 translocated NSCLC. Radiat Oncol. 2018;13:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fleschutz K, Walter L, Leistner R, Heinzerling L. ALK Inhibitors Do Not Increase Sensitivity to Radiation in EML4-ALK Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2020;40:4937-4946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Liang L, Mao M, Wu L, Chen T, Lyu J, Wang Q, Li T. Efficacy and Drug Resistance Analysis of ALK Inhibitors in Combination with Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Treating Lung Squamous Carcinoma Patient Harboring EML4-ALK Rearrangement. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;14:5385-5389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nardone V, Romeo C, D'Ippolito E, Pastina P, D'Apolito M, Pirtoli L, Caraglia M, Mutti L, Bianco G, Falzea AC, Giannicola R, Giordano A, Tagliaferri P, Vinciguerra C, Desideri I, Loi M, Reginelli A, Cappabianca S, Tassone P, Correale P. The role of brain radiotherapy for EGFR- and ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer with brain metastases: a review. Radiol Med. 2023;128:316-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Johnstone C, Rich SE. Bleeding in cancer patients and its treatment: a review. Ann Palliat Med. 2018;7:265-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Minici R, Guzzardi G, Venturini M, Fontana F, Coppola A, Spinetta M, Piacentino F, Pingitore A, Serra R, Costa D, Ielapi N, Guerriero P, Apollonio B, Santoro R, Mgjr Research Team, Brunese L, Laganà D. Transcatheter Arterial Embolization (TAE) of Cancer-Related Bleeding. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59:1323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Crane CH, Janjan NA, Abbruzzese JL, Curley S, Vauthey J, Sawaf HB, Dubrow R, Allen P, Ellis LM, Hoff P, Wolff RA, Lenzi R, Brown TD, Lynch P, Cleary K, Rich TA, Skibber J. Effective pelvic symptom control using initial chemoradiation without colostomy in metastatic rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49:107-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bezjak A, Dixon P, Brundage M, Tu D, Palmer MJ, Blood P, Grafton C, Lochrin C, Leong C, Mulroy L, Smith C, Wright J, Pater JL; Clinical Trials Group of the National Cancer Institute of Canada. Randomized phase III trial of single versus fractionated thoracic radiation in the palliation of patients with lung cancer (NCIC CTG SC.15). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54:719-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Kramer GW, Wanders SL, Noordijk EM, Vonk EJ, van Houwelingen HC, van den Hout WB, Geskus RB, Scholten M, Leer JW. Results of the Dutch National study of the palliative effect of irradiation using two different treatment schemes for non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2962-2970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Senkus-Konefka E, Dziadziuszko R, Bednaruk-Młyński E, Pliszka A, Kubrak J, Lewandowska A, Małachowski K, Wierzchowski M, Matecka-Nowak M, Jassem J. A prospective, randomised study to compare two palliative radiotherapy schedules for non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1038-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Duchesne GM, Bolger JJ, Griffiths GO, Trevor Roberts J, Graham JD, Hoskin PJ, Fossâ SD, Uscinska BM, Parmar MK. A randomized trial of hypofractionated schedules of palliative radiotherapy in the management of bladder carcinoma: results of medical research council trial BA09. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:379-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yan J, Milosevic M, Fyles A, Manchul L, Kelly V, Levin W. A hypofractionated radiotherapy regimen (0-7-21) for advanced gynaecological cancer patients. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2011;23:476-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hartsell WF, Scott CB, Bruner DW, Scarantino CW, Ivker RA, Roach M 3rd, Suh JH, Demas WF, Movsas B, Petersen IA, Konski AA, Cleeland CS, Janjan NA, DeSilvio M. Randomized trial of short- versus long-course radiotherapy for palliation of painful bone metastases. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:798-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 582] [Cited by in RCA: 542] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhang G, Zhang J, Gao Q, Zhao Y, Lai Y. Clinical and immunologic features of co-infection in COVID-19 patients, along with potential traditional Chinese medicine treatments. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1357638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Duan T, Li L, Yu Y, Li T, Han R, Sun X, Cui Y, Liu T, Wang X, Wang Y, Fan X, Liu Y, Zhang H. Traditional Chinese medicine use in the pathophysiological processes of intracerebral hemorrhage and comparison with conventional therapy. Pharmacol Res. 2022;179:106200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/