INTRODUCTION

Despite its ubiquity - affecting approximately 7%-9% of individuals - appendicitis often presents with atypical symptoms that limit diagnostic certainty[1]. While the classic progression of peri-umbilical pain migrating to the right lower quadrant, accompanied by anorexia, nausea, and low-grade fever, is well-known, many patients deviate from this archetype[2]. Clinical examination and laboratory indicators such as elevated white blood cell count or C-reactive protein offer diagnostic clues but lack sufficient sensitivity or specificity in isolation[3]. As a result, imaging has assumed a central role in the diagnostic pathway. Guidelines from major surgical and radiologic societies advocate for risk-stratified imaging based on clinical scoring systems, such as the Alvarado score, the Pediatric Appendicitis Score, or the Appendicitis Inflammatory Response score, the latter of which has been shown to outperform others in predictive value[4].

These scoring systems enable classification into low, intermediate, or high risk for appendicitis, which in turn determines the appropriate imaging strategy[4]. For instance, in intermediate-risk patients, ultrasound is typically recommended as the first-line modality, with further cross-sectional imaging like computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reserved for equivocal cases[5]. In adults, CT remains the standard with sensitivities ranging from 85.7% to 100% and specificities ranging from 94.8% to 100%. However, the growing concerns about radiation exposure, particularly in younger and pregnant patients, have propelled the increased use of MRI in select populations[6].

CT

CT remains the cornerstone of appendicitis imaging in adult patients. Its high spatial resolution and rapid acquisition allow for detailed visualization of the appendix and surrounding structures[7]. The most consistent direct sign is appendiceal enlargement, typically defined as an outer wall-to-outer wall diameter greater than 6 mm[8]. Yet, this criterion must be interpreted with caution, as several studies have shown that up to 40% of normal appendices may exceed this diameter, especially when the lumen contains air or fluid. Consequently, secondary signs gain diagnostic importance[9].

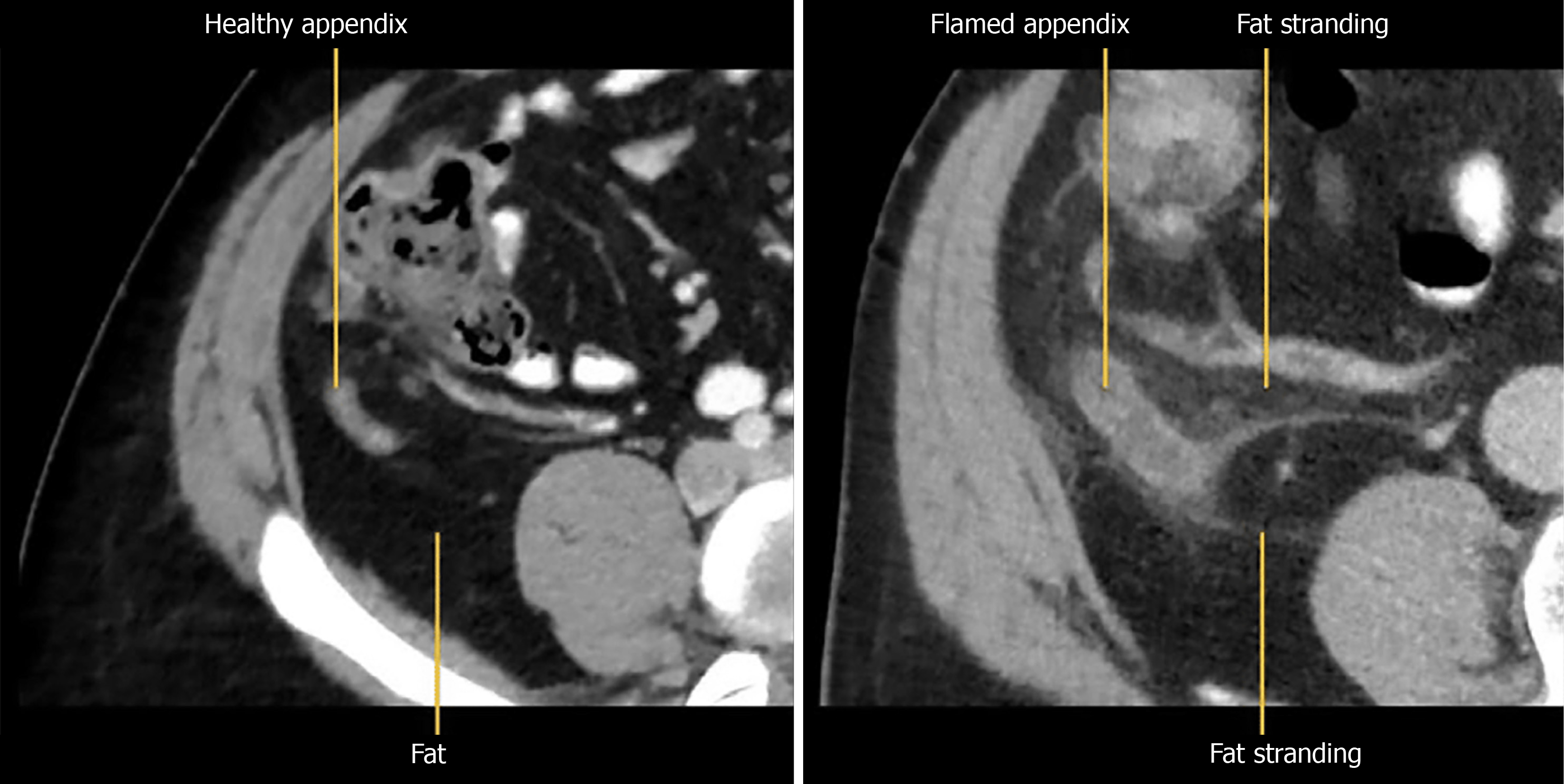

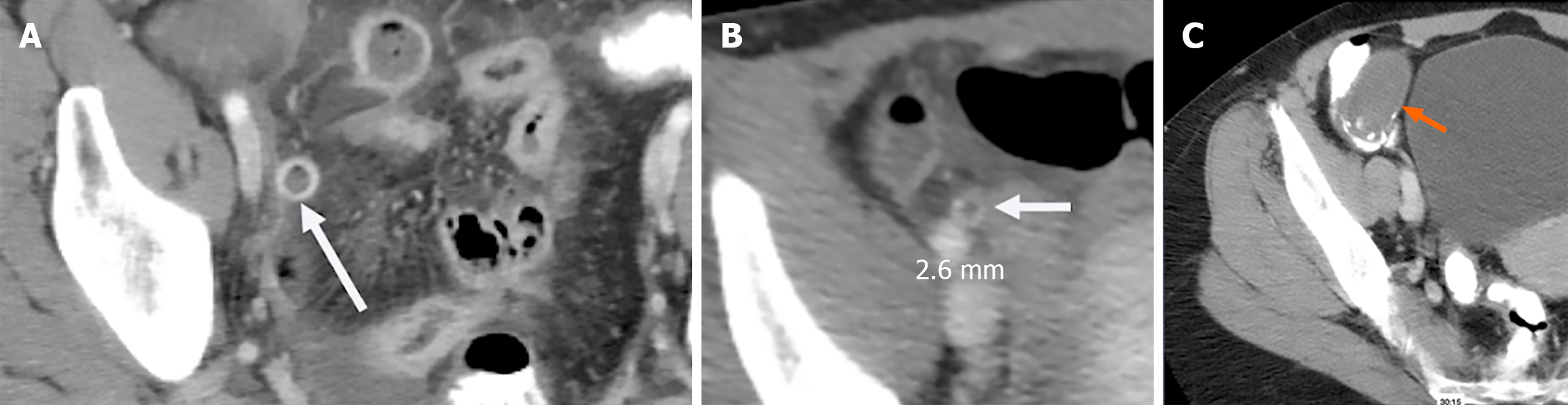

Among these secondary signs, peri-appendiceal fat stranding and fluid collections signify localized inflammation (Figure 1). The stranding appears as bright, inflamed fat surrounding the appendix and often correlates with symptom severity[10]. Wall thickening greater than 3 mm and hyperenhancement following contrast administration are additional indicators of appendicitis (Figure 2A)[11]. A particularly specific but less common finding is the presence of airless, low-attenuation fluid within the lumen (Figure 2B). This fluid type is rare in normal appendices and may signify early mucosal involvement. A threshold of 2.6 mm of fluid within the appendix has shown strong diagnostic performance[9,12].

Figure 1 On the left is a computed tomography image of normal healthy appendix while on the right is an inflamed appendix with fat stranding.

Figure 2 Image.

A: Computed tomography showing appendiceal wall hyperenhancement. White arrow: Inflamed, enhancing appendiceal wall consistent with acute appendicitis; B: Computed tomography showing airless, low attenuation fluid in the lumen, a frequently useful sign in early appendicitis. White arrow: Fluid-filled, non-aerated lumen measuring 2.6 mm, indicating early mucosal inflammation; C: Distended appendix fluid filled, curvilinear calcifications at base with airless low attenuation fluid, which was identified as a mucocele (orange arrow).

Complications such as perforation can be inferred from findings like extraluminal air, abscess formation, or loss of wall enhancement indicating necrosis[13,14]. These signs alter management significantly and necessitate surgical or percutaneous intervention. Importantly, CT interpretation must be contextualized within the clinical picture, as radiologic findings may be misleading in the absence of supportive clinical evidence[15].

DIAGNOSTIC CHALLENGES AND MIMICS

CT, while powerful, is not infallible. Missed diagnoses may result from perceptual errors or from overreliance on the presence of luminal air to exclude appendicitis[15]. In reality, up to 31% of confirmed appendicitis cases may contain intraluminal air. Conversely, false positives may arise from conditions such as mucoceles, mucinous cystadenomas, lymphomas, or cecal obstruction. These pathologies can mimic an inflamed appendix due to overlapping imaging features such as distension and fluid content[16,17]. When you see airless low attenuation fluid-filled appendices, it is imperative to look at the cecum for obstruction Figure 2C.

Peri-appendicitis presents a unique diagnostic dilemma. In this entity, the surrounding fat becomes inflamed, but the appendix itself remains unaffected. It is often secondary to another intra-abdominal pathology, and differentiating it from true appendicitis requires a nuanced understanding of imaging findings in conjunction with clinical data[18].

INCIDENTAL AND NON-VISUALIZED APPENDIX

In rare cases, an appendix appearing inflamed on imaging may be found incidentally in asymptomatic individuals; this mostly presents as a hypermetabolic area on fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT in specific cohorts such as cancer patients[19,20]. In such scenarios, further clinical correlation is imperative. Not all radiologic signs mandate intervention, particularly when the patient lacks symptoms. Another diagnostic challenge arises when the appendix is not visualized[21]. Thin-section reconstructions and coronal reformatting may aid in detection, but in some cases, the appendix remains elusive[22]. If no secondary signs such as localized fat stranding or regional ileus are present, the likelihood of appendicitis is low, around 2%[21]. However, if right lower quadrant inflammation is seen without another clear etiology (such as Crohn’s disease, diverticulitis, gynecological infections), the diagnosis cannot be confidently excluded with appendicitis seen in around 26% of cases[23].

DEFERRED TREATMENT AND RECURRENT APPENDICITIS

Patients discharged after an initial presentation that did not fulfill the criteria for appendicitis occasionally return with definitive symptoms. Data suggest that approximately 38% of such patients eventually develop appendicitis, often within a year of the initial visit[24,25]. These delayed presentations are more likely to involve complications such as perforation. This raises the question of whether some cases represent a chronic or smoldering inflammatory process rather than a purely acute event[26,27].

MRI AND ULTRASOUND

In pregnant patients, appendicitis represents the most common non-obstetric surgical emergency[28]. Given the potential teratogenic effects of ionizing radiation, ultrasound is the preferred first-line imaging modality[29]. However, its limitations are well-documented, particularly as the gravid uterus displaces abdominal contents. When ultrasound is inconclusive, MRI has emerged as a reliable, safe, and effective alternative. MRI protocols for suspected appendicitis include axial, coronal, and sagittal SSFSE or HASTE sequences, axial T1-weighted images, and optionally fat-saturated T2 sequences. These allow for confident localization of the cecum and appendix, and provide insights into alternate causes of abdominal pain[30,31].

MRI is gaining ground in non-pregnant populations as well, particularly children and adolescents, where radiation avoidance is paramount. Studies have demonstrated diagnostic performance comparable to CT in children and young adults (sensitivity and specificity were 85.9% and 93.8% for unenhanced MRI, 93.6% and 94.3% for contrast-enhanced MRI, and 93.6% and 94.3% for CT), with the added benefit of identifying other intra-abdominal pathologies[6,32]. Limitations remain, including availability, scan time, and the need for patient cooperation, but these are being progressively mitigated with faster sequences and improved protocols.

CONCLUSION

Imaging is indispensable in the modern management of suspected appendicitis. CT offers unparalleled anatomical detail and is the modality of choice in adult patients with moderate to high clinical suspicion. Interpretation should be guided not by a single finding but by a constellation of signs, including appendiceal enlargement, peri-appendiceal inflammation, wall thickening, enhancement, and the presence of fluid or extraluminal air. Awareness of potential pitfalls, such as isodense enlarged appendices and non-visualized cases, is crucial to avoid misdiagnosis.

MRI and ultrasound have well-established roles in specific populations and clinical contexts. MRI, in particular, is becoming more prevalent due to its diagnostic accuracy and absence of ionizing radiation. For pregnant patients and children, it offers a safe and effective alternative when ultrasound is inconclusive.

Future directions include the refinement of imaging protocols, better integration of clinical risk scores with imaging findings, and the exploration of artificial intelligence in image interpretation. Importantly, imaging findings should always be interpreted in conjunction with the clinical evaluation, as radiologic appearances alone may be misleading. Radiologists must therefore remain vigilant, adaptable, and informed to optimize diagnostic accuracy and guide patient management appropriately.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Novelty: Grade C, Grade C, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade C, Grade C, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade C, Grade C

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Bake JF, MD, Assistant Professor, Congo; Mohammed Ali U, Associate Research Scientist, Chief, Head, Senior Scientist, Ethiopia S-Editor: Bai Y L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG