Published online Dec 22, 2025. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v16.i4.112536

Revised: August 13, 2025

Accepted: October 29, 2025

Published online: December 22, 2025

Processing time: 145 Days and 17 Hours

Gastric motility is an essential gastrointestinal function. It can be influenced by age, gender, body composition, and metabolic status. However, published data on these associations remains limited.

To assess the relationship between gastric motility and adiposity, and metabolic indicators in a cohort of Sri Lankan office workers.

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 130 office workers (58.5% females) aged 20-50 years (mean 36.81, SD 8.85 years) of the University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. Gastric motility was assessed by real-time ultrasonography, using a pre

The mean body mass index (BMI) was 24.36 (SD 4.09) kg/m2, and 39.2% were overweight or obese. Increased abdominal adiposity was detected in 29.2% and 40.8% had high waist-to-hip ratios. Prediabetes/diabetes were observed in 20.0%, hypercholesterolemia in 47.7%, hypertriglyceridemia in 14.7%, high low-density lipoproteins in 39.2%, and elevated aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase in 5.4% and 21.5% respectively. FAA had a weak negative correlation with high-density lipoprotein level (r = -0.227, P = 0.009), and a positive correlation with waist circumference (r = 0.235, P = 0.007), and waist-to-hip ratio (r = 0.244, P = 0.005). GER and AA1 correlated weakly with triglyceride (GER: r = 0.174, P = 0.048; AA1: r = 0.194, P = 0.027) and VLDL levels (GER: r = 0.183, P = 0.038; AA1: r = 0.195, P = 0.026). In females, AA1 positively correlated with triglycerides (r = 0.333, P = 0.003), and VLDL levels (r = 0.337, P = 0.003), and AA15 with BMI (r = 0.284, P = 0.013) and hip circumference (r = 0.229, P = 0.047). FAC negatively correlated with BMI (r = -0.234, P = 0.042) and hip circumference (r = -0.247, P = 0.032).

Gastric motility parameters showed weak associations with metabolic indicators, particularly lipid profiles, and to a lesser extent, with adiposity indicators. The greater number of correlations observed in females suggests the possibility of sex-specific differences in these associations. These findings highlight potential relationships that require confirmation through longitudinal studies.

Core Tip: This study investigated gastric motility in a cohort of Sri Lankan office workers, focusing on its associations with body mass index, adiposity, and metabolic indicators. Males showed significantly larger fasting antral areas, while in females, gastric motility was more closely linked to measures of adiposity and lipid profiles. These findings underscore the influence of metabolic status, particularly lipid metabolism, on gastric motor function, with notable sex-specific patterns. The results provide new insights into the potential impact of metabolic derangements on gastrointestinal physiology and support early identification of individuals at risk for motility disorders.

- Citation: Basnayake PI, Kottahachchi D, Chandran DS, Medagoda K, Devanarayana NM. Gastric motility and its association with adiposity and metabolic health in a cohort of Sri Lankan office workers. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2025; 16(4): 112536

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v16/i4/112536.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v16.i4.112536

Gastric motility plays a key role in the gastrointestinal functions of digestion and absorption. Well-coordinated proximal stomach accommodation and rhythmic antral peristalsis facilitate storage of food, mechanical and chemical digestion, and controlled emptying. The amplitude and velocity of antral peristalsis, which progressively increase towards the pylorus, are the main determinants of effective titration of food and gastric emptying[1,2]. Their dysfunction has been postulated as a main underlying pathophysiology for disorders of gut-brain interaction (e.g., functional dyspepsia), gastroparesis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease[3,4].

With societal development, an increasing proportion of the workforce is engaged in office-based occupations, con

According to the STEPS Survey 2021, the prevalence of overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) in Sri Lanka was 39.4%, and obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) was 11.0%, among the 18-69 years age group[15]. The combination of excessive food intake and a predominantly sedentary lifestyle among office workers makes them an ideal population for investigating the relationship between adiposity, metabolic disturbances, and altered gastric motility. The main objective of the current study was to assess these relationships in a cohort of Sri Lankan office workers.

This was a cross-sectional observational study conducted from November 2024 to May 2025.

Gastroenterology Research Laboratory, Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka.

Inclusion criteria: Staff members of the University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka, aged between 20 and 50 years, not engaging in any routine or structured physical activity, and who voluntarily provided written informed consent, were included.

Exclusion criteria: A history of gastrointestinal, liver, or pancreatic diseases; previous gastrointestinal surgery other than appendicectomy; subjects on medications affecting gastric motility; and unconsented individuals were excluded.

Anthropometric measurements: The same trained investigator measured all the anthropometric parameters. Participants’ body weight and height were measured while they were barefoot and wearing light clothing. A highly sensitive digital flat scale (seca 813) was used to record body weight to the nearest 0.01 kg, and height was measured to the nearest 1 mm using a standard stadiometer (seca 213) according to recommended guidelines[16]. BMI was calculated using the formula, weight (kg)/height2 (m2). Participants were categorized into six weight groups based on the BMI classifications provided by the Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka[17] (Supplementary Table 1).

The waist and hip circumferences were measured to the nearest 1 mm using a non-stretchable measuring tape. The waist measurement was taken at the end of a normal expiration with the arms relaxed at the sides and at the midpoint between the lower margin of the last palpable rib and the top of the iliac crest. The maximum circumference over the buttocks with the arms relaxed at the side was taken as the waist circumference[16]. Abdominal obesity, according to the waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio, was calculated in males and females based on the Sri Lankan guidelines[17] (Supplementary Table 2).

Skinfold thickness was measured (biceps, triceps, subscapular, suprailiac, abdominal, front thigh, and medial calf sites) on the right-hand side of the body to the nearest 1 mm using a standard skinfold caliper. Body fat percentage was predicted using Jackson and Pollock's 4-site (abdominal, triceps, thigh, and suprailiac) skinfold equations[18].

For males: Body fat% = (0.29288 × sum of skinfolds) – (0.0005 × square of the sum of skinfolds) + (0.15845 × age) – 5.76377.

For females: Body fat% = (0.29669 × sum of skinfolds) – (0.00043 × square of the sum of skinfolds) + (0.02963 × age) + 1.4072.

Metabolic functions: Venous blood samples (5 mL) were collected from the participants under aseptic conditions after 12 hours of fasting. All measurements were done from an accredited laboratory. Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels were measured using the Bio-Rad D-10 Hemoglobin Testing System, and lipid profile [total cholesterol, triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein, cholesterol to HDL ratio, very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), non-HDL cholesterol] and lever enzyme [Aspartate transaminase (SGOT) and Alanine transaminase (SGPT)] levels were measured using the Cobas C311 Analyzer. The cutoff values for diabetes and dyslipidemia were based on the Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka National Guidelines[19,20] (Supplementary Table 3).

Gastric motility parameters: Medications affecting gastric motility (e.g., prokinetics, erythromycin, adrenergic and cholinergic drugs) were stopped 48 hours before the test. All gastric motility parameters were evaluated in the morning (8.00 am to 9.00 am), on the same day as anthropometric and metabolic testing, using a previously validated method[21].

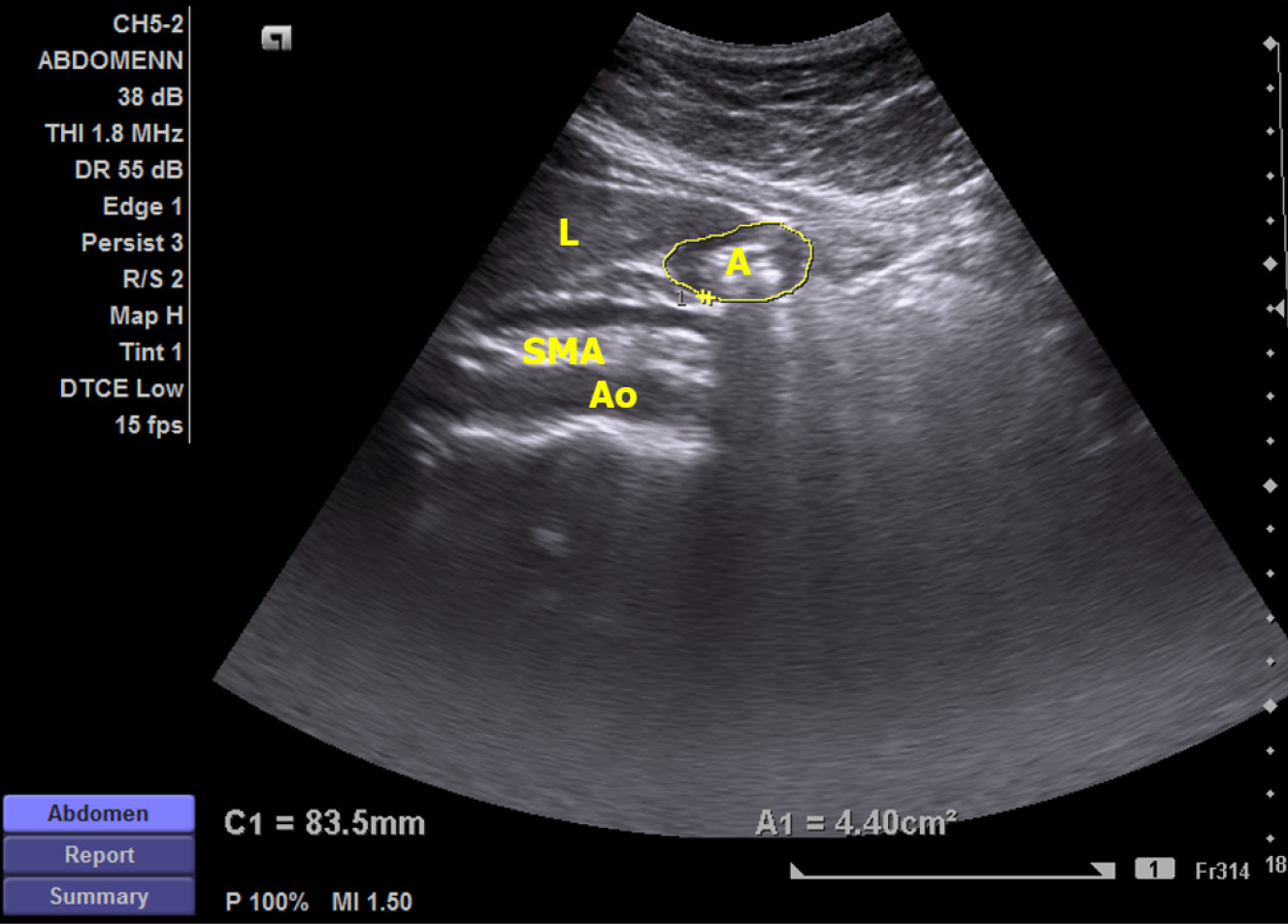

The tests were performed using a high-resolution real-time scanner (Siemens ACUSON X300™) with a 1.8 MHz to 6.4 MHz curved linear transducer with facilities to record and playback. The scan was performed in the sagittal scanning plane (Figure 1). The subjects were examined sitting at 450 to the horizontal, in the fasting stage and immediately after consuming a 200 mL standard liquid test meal, heated to approximately 40 °C, within 2 minutes (chicken broth, 54.8 KJ, 0.38 g proteins, 0.25 g fat, 2.3 g sugar per serving, Ajinomoto Co, Tokyo, Japan).

The main gastric motility parameters assessed were fasting antral area (FAA), after-meal antral area at 1 minute (AA1) and 15 minutes (AA15), antral area at contraction and relaxation, and frequency of antral contractions (FAC). Based on these values, gastric emptying rate (GER), amplitude of antral contractions (AAC), and antral motility index (AMI) were calculated using the equations below.

GER (%) = [Antral area at 1 minute (cm2) – Antral area at 15 minutes (cm2)]/[Antral area at 1 minute (cm2)] × 100.

AAC (%) = [Antral area at relaxation (cm2) – Antral area at contraction (cm2)]/[Antral area at relaxation (cm2)] × 100.

AMI = [AAC (%) × Frequency of antral contractions for 3 minutes]/100.

Sample size was estimated according to the method described by Cohen[22]. At an 80% (β = 0.2) of statistical power and a significant level of 5% (α = 0.05), to detect a medium-sized effect (r = 0.3) between gastric motility parameters and adiposity/metabolic indicators, the minimum sample required for this observational study was 85.5. However, to improve the statistical precision and facilitate subgroup analysis, 130 participants were included in the analysis.

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 21). Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize participants' characteristics. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD, while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Bivariate analyses were conducted using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient to evaluate associations, while means were compared using the independent samples t-test. Comparisons across different groups were conducted using one-way ANOVA. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka (Ref. No: P/127/09/2022).

The study included 130 office workers aged 20 and 50 years (mean 36.81, SD 8.85 years). The sample comprised 76 females (58.5%) and 54 males. The mean age of male participants was 39.37 (SD 7.48) years, while that of females was 35.00 (SD 9.35) years.

The mean BMI of the sample was 24.36 (SD 4.09) kg/m2. The percentage distribution of participants according to categories of age, adiposity, and metabolic markers is summarized in Table 1. Descriptive statistics of body composition and metabolic indicators are presented according to the total sample and by gender in Table 2. The mean waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, triglycerides, VLDL, cholesterol-to-HDL ratio, SGOT, and SGPT levels were significantly higher in males compared to females. The mean body fat percentage was significantly higher in females.

| Parameter | Category | Percentage distribution | ||

| Total (n = 130) | Male (n = 54) | Females (n = 76) | ||

| Age (years) | 20–30 | 35 (26.9) | 9 (16.7) | 26 (34.2) |

| 31-40 | 41 (31.5) | 15 (27.8) | 26 (34.2) | |

| 41-50 | 54 (41.5) | 30 (55.5) | 24 (31.6) | |

| Adiposity measures | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Underweight | 6 (4.6) | 3 (5.6) | 3 (3.9) |

| Normal | 73 (56.2) | 32 (59.3) | 41 (53.9) | |

| Overweight | 40 (30.8) | 16 (29.6) | 24 (31.6) | |

| Obesity - class 1 | 9 (6.9) | 3 (5.6) | 6 (7.9) | |

| Obesity - class 2 | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.6) | |

| Body fat (%) | Normal | 127 (97.7) | 53 (98.1) | 74 (97.4) |

| Overweight/obese | 3 (2.3) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (2.6) | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | Normal | 92 (70.8) | 45 (83.3) | 47 (61.8) |

| Abdominal adiposity | 38 (29.2) | 9 (16.7) | 29 (38.2) | |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | Normal | 77 (59.2) | 41 (75.9) | 36 (47.4) |

| Health risk | 53 (40.8) | 13 (24.1) | 40 (52.6) | |

| Metabolic parameters | ||||

| HbA1c (%) | Normal | 104 (80.0) | 41 (75.9) | 63 (82.9) |

| Pre-diabetes | 19 (14.6) | 9 (16.7) | 10 (13.2) | |

| Diabetes | 7 (5.4) | 4 (7.4) | 3 (3.9) | |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | Desirable | 68 (52.3) | 30 (55.6) | 38 (50.0) |

| Borderline high | 48 (36.9) | 18 (33.3) | 30 (39.5) | |

| High | 14 (10.8) | 6 (11.1) | 8 (10.5) | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | Normal | 111 (85.4) | 39 (72.2) | 72 (94.7) |

| Borderline high | 11 (8.5) | 8 (14.8) | 3 (3.9) | |

| High | 8 (6.2) | 7 (13.0) | 1 (1.3) | |

| HDL (mg/dL) | Low | 18 (13.8) | 13 (24.1) | 5 (6.6) |

| Normal | 82 (62.3) | 38 (70.4) | 43 (56.6) | |

| High | 31 (23.8) | 3 (5.6) | 28 (36.8) | |

| LDL (mg/dL) | Optimal | 27 (20.8) | 12 (22.2) | 15 (19.7) |

| Near-optimal | 52 (40.0) | 20 (37.0) | 32 (42.1) | |

| High/very high | 51 (39.2) | 22 (40.8) | 29 (38.2) | |

| Liver enzymes | ||||

| SGOT (U/L) | Normal | 123 (94.6) | 50 (92.6) | 73 (96.1) |

| Elevated | 7 (5.4) | 4 (7.4) | 3 (3.9) | |

| SGPT (U/L) | Normal | 102 (78.5) | 36 (66.7) | 66 (86.8) |

| Elevated | 28 (21.5) | 18 (33.3) | 10 (13.2) | |

| Parameter | Total (n = 130) | Male (n = 54) | Female (n = 76) | P value1 |

| mean ± SD | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | ||

| Body composition | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.36 ± 4.09 | 23.96 ± 3.79 | 24.64 ± 4.30 | 0.357 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 79.95 ± 11.07 | 83.59 ± 8.65 | 77.37 ± 11.90 | 0.001 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 96.73 ± 8.74 | 96.52 ± 7.85 | 96.88 ± 9.38 | 0.821 |

| Waist/hip | 0.83 ± 0.08 | 0.87 ± 0.06 | 0.80 ± 0.89 | < 0.001 |

| Body fat (%) | 17.03 ± 6.22 | 12.86 ± 4.66 | 19.99 ± 5.46 | < 0.001 |

| Metabolic indicators | ||||

| HbA1c (%) | 5.35 ± 0.81 | 5.44 ± 0.91 | 5.29 ± 0.74 | 0.315 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 197.36 ± 33.40 | 197.32 ± 36.98 | 197.40 ± 30.86 | 0.989 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 108.54 ± 47.21 | 130.01 ± 55.12 | 93.29 ± 33.46 | < 0.001 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 51.56 ± 12.24 | 45.19 ± 8.59 | 56.08 ± 12.48 | < 0.001 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 123.69 ± 30.67 | 126.02 ± 34.34 | 122.03 ± 27.90 | 0.467 |

| Cholesterol/HDL ratio | 3.97 ± 1.04 | 4.49 ± 1.11 | 3.60 ± 0.82 | < 0.001 |

| VLDL (mg/dL) | 21.35 ± 9.42 | 26.65 ± 10.97 | 18.30 ± 6.70 | < 0.001 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 145.05 ± 33.43 | 151.65 ± 37.04 | 140.37 ± 29.99 | 0.058 |

| SGOT/AST (U/L) | 23.07 ± 9.70 | 27.18 ± 9.52 | 20.15 ± 8.77 | < 0.001 |

| SGPT/ALT (U/L) | 28.82 ± 21.07 | 39.80 ± 22.31 | 21.01 ± 16.46 | < 0.001 |

Table 3 describes the gastric motility parameters in the total sample and by gender. The results showed that the mean FAA was significantly higher in males compared to females (P = 0.025). Other gastric motility parameters were not different between males and females.

| Gastric motility parameter | Total (n = 130) | Male (n = 54) | Female (n = 76) | P value1 |

| mean ± SD | mean ± SD | mean ± SD | ||

| Fasting antral area (cm2) | 6.32 ± 2.56 | 6.92 ± 2.73 | 5.90 ± 2.35 | 0.025 |

| Antral area in 1 minute (cm2) | 17.03 ± 4.73 | 16.83 ± 4.38 | 17.18 ± 4.98 | 0.678 |

| Antral area in 15 minutes (cm2) | 12.48 ± 4.13 | 12.57 ± 4.59 | 12.42 ± 3.79 | 0.836 |

| Frequency of antral contractions (3 minutes) | 9.16 ± 0.94 | 9.20 ± 1.02 | 9.13 ± 0.89 | 0.668 |

| Gastric emptying rate (%) | 25.48 ± 20.36 | 24.33 ± 23.21 | 26.30 ± 18.18 | 0.588 |

| Amplitude of antral contractions (%) | 43.71 ± 14.70 | 42.02 ± 14.85 | 44.91 ± 14.58 | 0.271 |

| Antral motility index | 4.03 ± 1.49 | 3.89 ± 1.51 | 4.13 ± 1.49 | 0.364 |

One-way ANOVA revealed that FAA differed significantly between groups, F (2,127) = 3.861, P = 0.024 (Table 4). Post-hoc Tukey analysis showed that participants in the age group 41-50 years had a significantly larger FAA compared with those in the age group 20-30 years (mean difference = 1.51 cm2, P = 0.017). Other motility parameters, including GER, FAC, AAC, AA1, and AA15, did not show significant differences across age categories (P > 0.05).

| Gastric motility parameter | Age group | ||

| 20-30 years | 31-40 years | 41-50 years | |

| Fasting antral area (cm2) | 5.41 ± 2.50 | 6.33 ± 2.29 | 6.92 ± 2.651 |

| Antral area in 1 minute (cm2) | 17.38 ± 6.13 | 15.74 ± 3.70 | 17.78 ± 4.24 |

| Antral area in 15 minutes (cm2) | 12.15 ± 4.39 | 12.25 ± 3.62 | 12.87 ± 4.35 |

| Frequency of antral contractions (3 minutes) | 9.11 ± 0.93 | 9.29 ± 0.93 | 9.09 ± 0.96 |

| Gastric emptying rate (%) | 29.26 ± 13.88 | 21.37 ± 20.10 | 26.16 ± 23.61 |

| Amplitude of antral contractions (%) | 42.79 ± 14.03 | 44.57 ± 15.48 | 43.65 ± 14.76 |

| Antral motility index | 3.94 ± 1.49 | 4.17 ± 1.61 | 3.99 ± 1.43 |

FAA showed a weak but statistically significant positive correlation with waist circumference (r = 0.235, P = 0.007, Spearman correlation coefficient) and waist-to-hip ratio (r = 0.244, P = 0.005), and a negative correlation with age

When the subgroup analysis was performed according to gender, in female participants, FAA (r = 0.399, P < 0.001), AA1 (r = 0.269, P = 0.019), and AA15 (r = 0.258, P = 0.024) showed a weak but significant positive correlation with age. AA15 demonstrated weak positive correlations with BMI (r = 0.284, P = 0.013) and hip circumference (r = 0.229, P = 0.047). FAC showed a weak negative correlation with BMI (r = -0.234, P = 0.042), and hip circumference (r = -0.247, P = 0.032). AA1 showed weak positive correlations with triglyceride (r = 0.333, P = 0.003) and VLDL (r = 0.337, P = 0.003) levels. In females, no statistically significant correlations were observed between GER, AAC, and AMI with age, body composition, or lipid profile (Supplementary Table 5).

None of the motility parameters had a statistically significant correlation with adiposity indicators or lipid profile in male participants.

No significant differences were observed between mean gastric motility parameters by low (< 25 kg/m2) and high (≥ 25 kg/m2) BMI, nor other adiposity, metabolic, and liver enzyme subcategories (P > 0.05).

This study investigated the relationship between gastric motility parameters and indicators of adiposity, glycemic status, lipid profile, and liver functions in a cohort of office workers in Sri Lanka. This is the first study to assess such rela

We assessed gastric motility parameters of Sri Lankan office workers according to age and gender for the first time. It has been reported that females have slower gastric emptying for both solid and liquid meals[23,24]. The mechanism suggested for this was the effect of female sex hormones, particularly estradiol and progesterone, on the gastrointestinal system[23,25]. However, some other studies assessing gastric emptying following both solid and liquid meals have shown identical gastric emptying for males and females[26]. Similarly, we did not find a significant difference in gastric emptying between males and females. However, in the current study, FAA, which is an indirect indicator of fasting gastric distension, was larger in males compared to females. The inversion of the results in our study may be due to the increased abdominal adiposity in the male subgroup, which affects autonomic modulation and gastric tone[27,28]. In addition, the male subgroup in our study demonstrated higher mean HbA1c levels and triglyceride levels compared to the female subgroup, suggesting a higher metabolic dysfunction, which was known to delay the gastric emptying[27].

Even with limited clinical significance, age-associated changes in gastric motility were observed in previous studies[29-31]. Age-related progressive autonomic dysfunction was believed to be the major cause of delayed gastric emptying[32]. It was reported that the larger antral area at rest, impaired antral compliance, and enhanced postprandial emptying are associated with aging[33]. Furthermore, age is a recognized risk factor for chronic metabolic diseases such as hypergly

When gastric motility parameters were correlated with adiposity indicators, we found a positive correlation between FAA and waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio. Our findings are compatible with a previous study conducted among moderately obese vs non-obese subjects using non-invasive single-photon emission computed tomography[34], which revealed that the fasting volume of the distal stomach was greater in obese individuals. This suggests that increased adiposity is associated with fasting antral dilatation. The exact underlying mechanism for this relationship is not clear, but previous studies have suggested that increased abdominal fat mechanically delays gastric motility or affects the autonomic regulation of the gastric motility[35-37].

In our study, we did not observe significant differences in gastric motility parameters among individuals with elevated BMI and dyslipidemia. There are no previous adult studies assessing this association. However, a previous study in Sri Lanka assessing the association between BMI and gastric motility in children with disorders of the gut-brain axis and controls reported a significantly larger FAA and AA1 in healthy controls[38].

GER and AA1 were weakly but positively correlated with triglycerides and VLDL levels. We did not find a significant correlation between other gastric motility parameters and BMI, adiposity, and metabolic indicators when the whole sample was analyzed. However, during subgroup analysis, in females, the postprandial motility parameter, AA15, showed a weak positive correlation with BMI and hip circumference, whereas the FAC showed a negative correlation with the same anthropometry measurements. These results are consistent with previous studies that have reported the impact of obesity on gastric motility[5,6,39-42]. Our findings suggest a potential association between higher postprandial gastric retention and reduced gastric contractility in females with greater adiposity. However, these associations were observed without adjusting for potential confounding factors, such as age. Additionally, the lack of significant correlations in males does not preclude the presence of similar associations in other populations.

According to Kong and Horowitz[14], delayed gastric emptying was observed more than rapid emptying among randomly selected patients with long-standing type 1 or type 2 diabetes after solid or liquid nutrient meals. Another study conducted among type 2 diabetes patients using an ultrasound technique has demonstrated delayed gastric emptying and reduced antral contractions compared to controls[43]. This finding aligns with previous evidence indicating that delayed gastric emptying is a common complication of diabetic neuropathy[44,45]. However, in contrast to previous research, we did not observe a significant association between gastric motility parameters and HbA1c levels. This may be due to the small number of participants with elevated HbA1c and the predominance of participants with normal HbA1c levels. However, another longitudinal study conducted over 12 years among patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes also reported no change in gastric emptying for both solid and liquid components[46].

This study has several strengths. This is the first study to evaluate the association between gastric motility and BMI, adiposity, and metabolic functions in office workers. Although many previous studies have investigated the above parameters independently, a comprehensive analysis of the association between adiposity, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and altered gastric motility is rare. Furthermore, most studies have concentrated on specific disease groups such as diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia. Office workers are engaged in desk work and spend most of their working hours seated, and often live a sedentary lifestyle. Associated lack of physical activity can lead to overweight and obesity and metabolic derailment. Furthermore, gastrointestinal dysmotility results in troublesome disorders such as constipation, gastroparesis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Identifying the relationship between gastric motility, BMI, adiposity, and metabolic functions would help in risk assessment. Among the methods used to investigate gastric motility, this study applied liquid gastric motility by ultrasonography as it is an accessible, safe, non-invasive, and cost-effective technique that can be used in both clinical and research settings.

The limitations of the study include that the study sample was confined to office workers from one higher educational institution in Sri Lanka, which may not represent the entire workforce, especially manual workers and those engaged in jobs with high physical activity levels. Furthermore, comparisons between occupational activity levels were not feasible in our study design, as the study sample was limited to sedentary office workers, and no active control group was included for comparison. Also, there are no local reference values for gastric motility parameters in Sri Lankan adults. Therefore, we were not able to classify participants into normal or impaired gastric motility subgroups. Instead, we categorized the participants into high and low BMI and other adiposity or metabolic subgroups and compared the mean values of gastric motility parameters between these subgroups. We also performed gender-specific correlations to identify relationships between gastric motility parameters and BMI, adiposity, and metabolic indicators. During the subgroup analysis, a small number of participants in some subgroups may have limited the power to detect true associations. In addition, we assessed gastric emptying using an ultrasound method, but not by scintigraphy, which is the gold standard. However, ultrasound techniques have been compared with simultaneously performed scintigraphy and proven to be accurate[47-49]. Furthermore, potential confounding factors, such as diet and use of medications, were not fully con

In our cohort of Sri Lankan office workers, abdominal adiposity and adverse lipid profile outcomes showed weak but statistically significant correlations with certain gastric motility parameters, particularly fasting and postprandial antral dilatation, which were most notable among females. Findings of the current study provide novel insights into the possible link between metabolic and gastrointestinal health in a sedentary adult working population, highlighting the need for longitudinal studies to explore this relationship further to identify underlying mechanisms and to initiate preventive measures.

We acknowledge Mrs. Ariyawansa J and Mr. Rathnayake P (Technical Officers), Mr. Chandana U, and Mr. Samarathunga B (Laboratory Attendants), and Mr. Perera S (Office Work Aid) at the Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka, for assistance in gastric motility test and data collection and Ms. Madhushani P, Technical Officer at the Department of Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka for development of the data base.

| 1. | O'Grady G, Du P, Cheng LK, Egbuji JU, Lammers WJ, Windsor JA, Pullan AJ. Origin and propagation of human gastric slow-wave activity defined by high-resolution mapping. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G585-G592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | O'Connor A, O'Moráin C. Digestive function of the stomach. Dig Dis. 2014;32:186-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lin ZY, McCallum RW, Schirmer BD, Chen JD. Effects of pacing parameters on entrainment of gastric slow waves in patients with gastroparesis. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:G186-G191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lin Z, Eaker EY, Sarosiek I, McCallum RW. Gastric myoelectrical activity and gastric emptying in patients with functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2384-2389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wright RA, Krinsky S, Fleeman C, Trujillo J, Teague E. Gastric emptying and obesity. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:747-751. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Tosetti C, Corinaldesi R, Stanghellini V, Pasquali R, Corbelli C, Zoccoli G, Di Febo G, Monetti N, Barbara L. Gastric emptying of solids in morbid obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996;20:200-205. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Mejía-Rivas M, Remes-Troche J, Montaño-Loza A, Herrera M, Valdovinos-Díaz MA. Gastric capacity is related to body mass index in obese patients. A study using the water load test. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2009;74:71-73. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Geliebter A. Gastric distension and gastric capacity in relation to food intake in humans. Physiol Behav. 1988;44:665-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Geliebter A, Hashim SA. Gastric capacity in normal, obese, and bulimic women. Physiol Behav. 2001;74:743-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen JD, Yin J, Wei W. Electrical therapies for gastrointestinal motility disorders. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11:407-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sato T, Nakamura Y, Shiimura Y, Ohgusu H, Kangawa K, Kojima M. Structure, regulation and function of ghrelin. J Biochem. 2012;151:119-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Camilleri M, Papathanasopoulos A, Odunsi ST. Actions and therapeutic pathways of ghrelin for gastrointestinal disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:343-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | O'Mahony D, O'Leary P, Quigley EM. Aging and intestinal motility: a review of factors that affect intestinal motility in the aged. Drugs Aging. 2002;19:515-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kong MF, Horowitz M. Gastric emptying in diabetes mellitus: relationship to blood-glucose control. Clin Geriatr Med. 1999;15:321-338. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Ministry of Health, Department of Census and Statistics. Non-communicable diseases risk factor survey (STEPS Survey), Sri Lanka. Colombo: Sumathi Printers (Pvt) Ltd; 2021. Available from: https://ncd.health.gov.lk/images/pdf/20230817_STEPS_Survey_new_1_compressed.pdf. |

| 16. | World Health Organization. Noncommunicable disease surveillance, monitoring, and reporting. STEPS Manual. Part 3, Section 5. Geneva: WHO, 2017: 358–359. Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/ncds/ncd-surveillance/steps/part3-section5.pdf?sfvrsn=a46653c7_2. |

| 17. | Ministry of Health, Nutrition and Indigenous Medicine, Sri Lanka. Guidelines on Management of Overweight and Obesity Among Adults in Sri Lanka. 1st ed. Colombo: Non-Communicable Disease Unit, Ministry of Health, 2018: 6. Available from: https://www.ncd.health.gov.lk/images/pdf/Guildlines/Guideline_Obesity.pdf. |

| 18. | Nevill AM, Metsios GS, Jackson AS, Wang J, Thornton J, Gallagher D. Can we use the Jackson and Pollock equations to predict body density/fat of obese individuals in the 21st century? Int J Body Compos Res. 2008;6:114-121. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Ministry of Health, Nutrition and Indigenous Medicine, Sri Lanka. National Guideline for Management of Diabetes for Secondary and Tertiary Healthcare Level. 1st ed. Colombo: Non-Communicable Diseases Unit, Ministry of Health, 2021: 9. Available from: https://www.ncd.health.gov.lk/images/pdf/circulars/final_dm_DM_for_secondary_and_tertiary__health_care_providers_feb3rd.pdf. |

| 20. | Ministry of Health, Nutrition and Indigenous Medicine, Sri Lanka. National Guideline for Management of Dyslipidaemia for Secondary and Tertiary Healthcare Level. 1st ed. Colombo: Non-Communicable Diseases Unit, Ministry of Health, 2021: 15. Available from: https://www.ncd.health.gov.lk/images/pdf/circulars/National_Dyslipidaemia_management_guideline.pdf. |

| 21. | Haruma K, Kusunoki H, Manabe N, Kamada T, Sato M, Ishii M, Shiotani A, Hata J. Real-time assessment of gastroduodenal motility by ultrasonography. Digestion. 2008;77 Suppl 1:48-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 1988. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Datz FL, Christian PE, Moore J. Gender-related differences in gastric emptying. J Nucl Med. 1987;28:1204-1207. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Mori H, Suzuki H, Matsuzaki J, Taniguchi K, Shimizu T, Yamane T, Masaoka T, Kanai T. Gender Difference of Gastric Emptying in Healthy Volunteers and Patients with Functional Dyspepsia. Digestion. 2017;95:72-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kassamali F, Lin MS. Gender Differences in Gastroparesis. Foregut. 2023;3:187-191. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Moore JG, Christian PE, Coleman RE. Gastric emptying of varying meal weight and composition in man. Evaluation by dual liquid- and solid-phase isotopic method. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:16-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Fidan-Yaylali G, Yaylali YT, Erdogan Ç, Can B, Senol H, Gedik-Topçu B, Topsakal S. The Association between Central Adiposity and Autonomic Dysfunction in Obesity. Med Princ Pract. 2016;25:442-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yalamudi K. Study of Comparison between Autonomic Dysfunction and Dyslipidemia in Healthy Postmenopausal Women. J Midlife Health. 2017;8:103-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pahlajrai N, Manas F, Kalsoom O, Bibi S, Asfandyar A, Ullah T. Gastrointestinal motility across ages: A comparative analysis of pediatric and adult population. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2024;31:2148-2155. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Tzakri T, Senekowitsch S, Wildgrube T, Sarwinska D, Krause J, Schick P, Grimm M, Engeli S, Weitschies W. Impact of advanced age on the gastric emptying of water under fasted and fed state conditions. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2024;201:106853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Madsen JL, Graff J. Effects of ageing on gastrointestinal motor function. Age Ageing. 2004;33:154-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Brogna A, Ferrara R, Bucceri AM, Lanteri E, Catalano F. Influence of aging on gastrointestinal transit time. An ultrasonographic and radiologic study. Invest Radiol. 1999;34:357-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Serra-Prat M, Mans E, Palomera E, Clavé P. Gastrointestinal peptides, gastrointestinal motility, and anorexia of aging in frail elderly persons. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:291-e245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kim DY, Camilleri M, Murray JA, Stephens DA, Levine JA, Burton DD. Is there a role for gastric accommodation and satiety in asymptomatic obese people? Obes Res. 2001;9:655-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | French SJ, Murray B, Rumsey RD, Sepple CP, Read NW. Preliminary studies on the gastrointestinal responses to fatty meals in obese people. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1993;17:295-300. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Wisén O, Hellström PM. Gastrointestinal motility in obesity. J Intern Med. 1995;237:411-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Camilleri M, Malhi H, Acosta A. Gastrointestinal Complications of Obesity. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1656-1670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Karunanayake A, Rajindrajith S, Kumari MV, Devanarayana NM. Effects of body mass index on gastric motility: Comparing children with functional abdominal pain disorders and healthy controls. World J Clin Pediatr. 2025;14:100306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 39. | Xing J, Chen JD. Alterations of gastrointestinal motility in obesity. Obes Res. 2004;12:1723-1732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M, Cremonini F, Ferber I, Stephens D, Burton DD. Contributions of gastric volumes and gastric emptying to meal size and postmeal symptoms in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1685-1694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Manolopoulos KN, Karpe F, Frayn KN. Gluteofemoral body fat as a determinant of metabolic health. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010;34:949-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 480] [Cited by in RCA: 599] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Granström L, Backman L. Stomach distension in extremely obese and in normal subjects. Acta Chir Scand. 1985;151:367-370. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Chiu YC, Kuo MC, Rayner CK, Chen JF, Wu KL, Chou YP, Tai WC, Hu ML. Decreased gastric motility in type II diabetic patients. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:894087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Abrahamsson H. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Intern Med. 1995;237:403-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Marathe CS, Rayner CK, Jones KL, Horowitz M. Novel insights into the effects of diabetes on gastric motility. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;10:581-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Jones KL, Russo A, Berry MK, Stevens JE, Wishart JM, Horowitz M. A longitudinal study of gastric emptying and upper gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 2002;113:449-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 47. | Hveem K, Jones KL, Chatterton BE, Horowitz M. Scintigraphic measurement of gastric emptying and ultrasonographic assessment of antral area: relation to appetite. Gut. 1996;38:816-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 48. | Benini L, Sembenini C, Heading RC, Giorgetti PG, Montemezzi S, Zamboni M, Di Benedetto P, Brighenti F, Vantini I. Simultaneous measurement of gastric emptying of a solid meal by ultrasound and by scintigraphy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2861-2865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Gomes H, Hornoy P, Liehn JC. Ultrasonography and gastric emptying in children: validation of a sonographic method and determination of physiological and pathological patterns. Pediatr Radiol. 2003;33:522-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/