INTRODUCTION

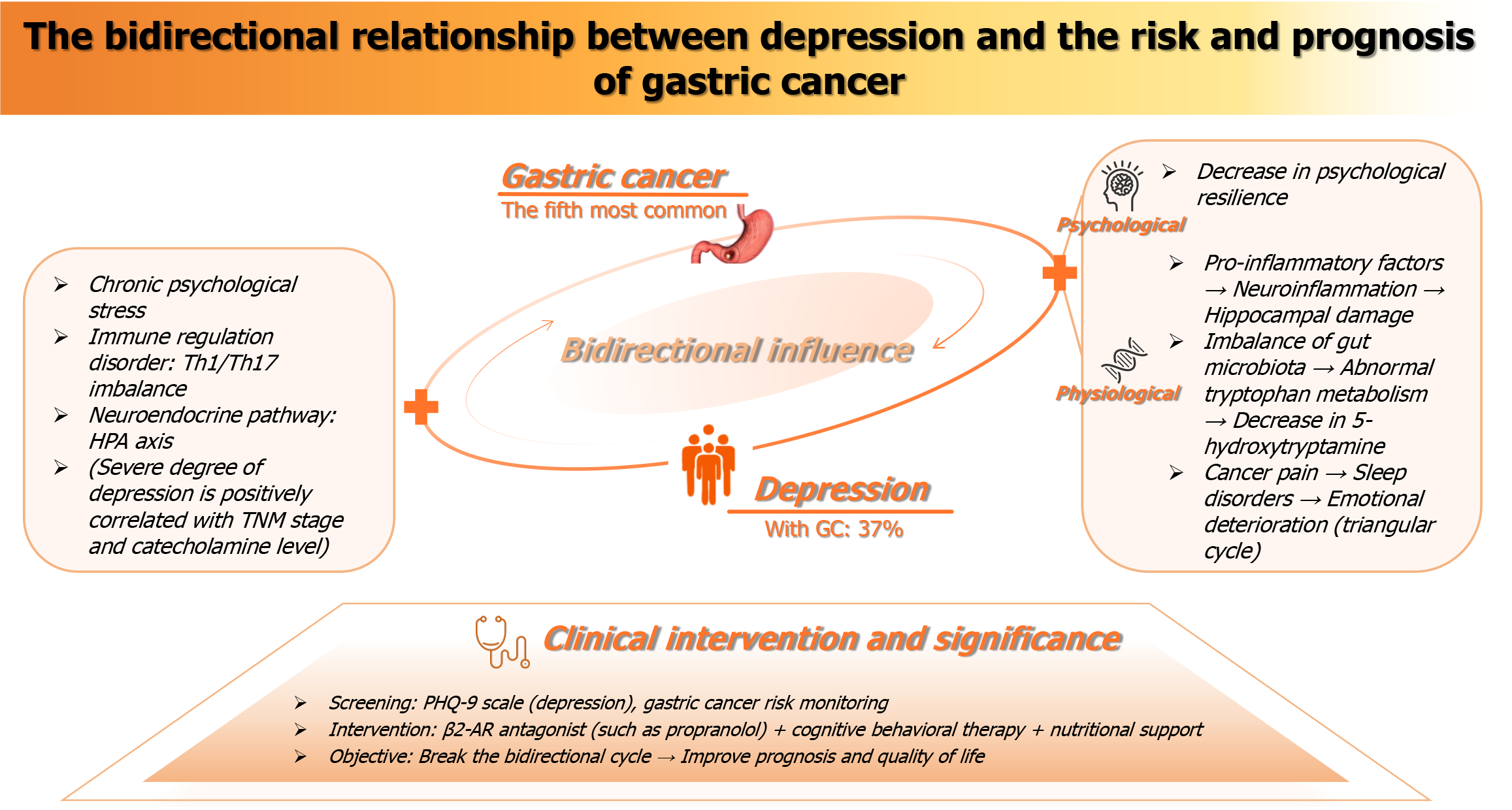

Gastric cancer (GC) is a primary epithelial malignant tumor originating in the stomach, and it is a complex and heterogeneous disease[1]. Currently, GC is the fifth most common cancer worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths. As a highly prevalent malignant tumor, it poses a serious threat to human health. Each year, more than 1 million new cases are reported, and because GC is often diagnosed at an advanced stage, the mortality rate remains very high. In 2018, GC caused 784000 deaths globally[2], and in 2020, it accounted for 1.089 million new cases and 769000 deaths[3]. Although treatment strategies have advanced considerably, including endoscopic resection for early-stage GC, D2 lymph node dissection combined with perioperative chemotherapy for locally advanced disease, and systemic therapy for metastatic GC, the median survival for patients with advanced cancer remains less than one year. Treatment-related side effects are also significant, such as nutritional and metabolic disorders following total gastrectomy (with 30%-50% of patients experiencing more than 10% weight loss) and vitamin deficiencies[4-7]. In addition, patients with GC often face heavy psychological burdens, including anxiety, depression, pain, and fatigue[8]. Depression is an emotional state characterized by a persistent low mood, frequently accompanied by reduced interest, loss of pleasure, fatigue, self-blame, and sleep disturbances. Studies suggest that the prevalence of anxiety and depression among patients with gastrointestinal cancers may be as high as 47.2% and 57%, respectively[9]. These psychological factors not only affect the attitudes of cancer patients but also influence treatment compliance and play a key role in determining overall quality of life. In addition, GC often causes ecological imbalance, which may result from tumor-related inflammation, changes in gastrointestinal secretions, and the effects of chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Such imbalance can promote chronic inflammation, accelerate the carcinogenic process, and impair immune function. Moreover, disruption of the microbial balance can influence the synthesis of neurotransmitters and other compounds that regulate brain function and cognition. The sentence structure can be simplified as follows: “Ecological imbalance may induce inflammation, allowing cytokines to cross the blood-brain barrier and potentially cause depressive symptoms”[10]. Therefore, both GC and depression can trigger cascade reactions that lead to systemic imbalance and reinforce each other in a complementary manner. When these two conditions occur simultaneously, they exacerbate the burden on patients and society. With the development of the biopsychosocial medical model, increasing numbers of studies have focused on the impact of psychological factors on disease treatment, and the association between depression and chemotherapy response in GC has gradually become a research hotspot. This minireview aims to systematically summarize research on depression and its relationship with the risk and prognosis of GC, synthesize existing results, and provide a theoretical basis for the development of more effective clinical interventions, improved GC treatment outcomes, and enhanced patient quality of life (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The overall introduction diagram of this minireview.

GC: Gastric cancer; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; β2-AR: Β2-adrenergic receptors; Th1: T helper 1 cell; Th17: T helper 1 cell; HPA: Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; TNM: Tumor-nodes-metastasis.

THE ROLE OF DEPRESSION IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF GC

Emotional disorders can accelerate the progression of chronic inflammatory diseases, including cancer[11]. Depression significantly reduces patients’ quality of life and increases cancer-related mortality[12,13]. One study reported that anxiety and depressive symptoms were observed in 18.3% and 24.0% of cancer patients, respectively, and that the incidence of mixed anxiety/depression symptoms was higher in patients with GC than in those with other cancers[14]. Another meta-analysis indicated that, compared with individuals without depressive symptoms, those with mild depressive symptoms had a 25% higher risk of death, while severe depression increased cancer-related mortality by 39%[15]. Collectively, these findings indicate that depression plays an important role in cancer development.

Chronic psychological stress, such as anxiety and depression, can promote the release of catecholamine neurotransmitters (e.g., norepinephrine and epinephrine) by activating the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis[16,17]. Excessive activation of the HPA axis can also lead to long-term elevation of cortisol levels[18]. Cortisol may indirectly accelerate the proliferation and spread of GC cells by inhibiting immune surveillance and promoting angiogenesis. Increased catecholamine expression in the tumor microenvironment can induce the proliferation, migration, and metastasis of many tumors, including gastrointestinal tumors. For instance, catecholamines contribute to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) through the c-Jun signaling pathway[19]. MACC1 is also highly expressed in GC metastasis. It was initially identified as an oncogene strongly associated with colorectal cancer metastasis. Subsequent studies confirmed its critical role in the malignant progression of various solid tumors, including GC. Moreover, its regulatory role in GC is multifaceted and occurs at multiple levels, including activation of the hepatocyte growth factor/MET signaling pathway.

Specifically, the binding of catecholamines to β2-adrenergic receptors (β2-AR) upregulates MACC1 expression, leading to neuroendocrine phenotypic transformation, GC invasion, and metastasis. Targeting β2-AR can mitigate the neuroendocrine phenotypic transformation and GC lung metastasis induced by depression, providing a potential therapeutic target for improving the prognosis of patients with GC and concurrent depression[20]. In addition, β2-AR stimulation may also induce EMT, migration, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylation-mediated invasion. Lu et al[21] observed that the β2-AR agonist salbutamol increased the expression of the mesenchymal marker N-cadherin in transplanted tumor tissues and decreased the epithelial marker E-cadherin, thereby inducing further EMT. Moreover, Lu et al[21] supported the view that the β2-AR agonist isoproterenol promotes GC cell EMT through the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3-CD44 pathway, thereby revealing an association between depression and GC[22]. Additionally, clinical studies have shown that levels of T helper (Th) 1 and Th17 cells are significantly increased in patients with depression. These immune cell subsets not only participate in the regulation of stress responses but also play a key role in the progression of GC[23]. The Th1 and Th17 pathways are chronically activated, leading to prolonged inflammation. Interestingly, high expression of the interleukin (IL)-17 receptor is a favorable prognostic indicator for survival after GC diagnosis[24]. A study by Nguyen and Putoczki[25] further suggested that consistent IL-17 signaling may represent a potential therapeutic target for GC. Notably, Pan et al[19] confirmed, using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), that the severity of depression is positively correlated with serum epinephrine, norepinephrine, MACC1 levels, and tumor-nodes-metastasis stage. This finding provides direct clinical evidence for interactions among the stress response, neuroendocrine activity, and the tumor microenvironment, and offers a theoretical basis for developing β2-AR-targeted interventions to improve the prognosis of patients with GC and concurrent depression. Furthermore, studies have shown that adverse psychological distress negatively affects the quality of life of cancer patients, leading to slower recovery and poorer survival rates[26], and imposing long-term burdens on both patients and their families[27-29].

THE ROLE OF GC IN DEPRESSION

GC is one of the malignant tumors with the highest incidence and mortality rates worldwide. Its clinical impact is not limited to organic damage to the digestive system and threats to life expectancy; through complex pathophysiological mechanisms and psychosocial interactions, patients with GC also face numerous mental health challenges, including anxiety, depression, pain, and fatigue. Kouhestani et al[5] reported that the prevalence of depression in patients with GC was 37%. The incidence of depression in this group was significantly higher than that observed in the general population and in patients with nonmalignant diseases[30]. A cancer diagnosis may cause psychological and emotional stress, and when such stress exceeds patients’ coping capacity, it may lead to severe depression. Although a diagnosis of cancer may trigger the rapid onset of psychological and emotional stress, the high incidence of depression in patients with GC may go beyond the scope of stress alone, indicating the involvement of additional contributing factors[31].

GC, as a major stress event, can induce depression through the interaction of psychological-cognitive processes and the social environment. Patients with GC may experience difficulties in reconstructing disease-related cognition, and some may develop catastrophic thinking, which excessively amplifies negative emotional experiences. In addition, patients may become overly sensitive to physical changes, resulting in a sense of loss of self-integrity, decreased self-efficacy, and a crisis of role identity, often manifested as helplessness and hopelessness[32]. The long treatment cycles and wide variability in GC prognosis place patients in a prolonged state of waiting-evaluation-retreatment uncertainty. This chronic and uncontrollable stress significantly reduces psychological resilience[33], thereby increasing susceptibility to depression. Moreover, patients’ emotions are influenced by accompanying symptoms. In advanced GC, patients may experience cancer-related pain, and pain and depression often form a pain-sleep disorder-emotional deterioration triangular cycle. Chronic pain can also exacerbate depression[34]. Chen et al[35] reported that appropriate psychological interventions, such as reminiscence therapy and narrative care, can reduce anxiety and depression.

Depressed patients exhibit varying patterns and severities of emotional disorders and clinical manifestations, which significantly affect patient prognosis[36,37]. This psychological disorder does not merely result from the stress response to a cancer diagnosis but is also closely related to the biological characteristics of the tumor, treatment-related physical damage, metabolic disorders, and neuroendocrine imbalance. Patients with GC often present with elevated plasma catecholamine levels. Research by Pan et al[19] has shown that patients with GC may indirectly contribute to the pathological process of depression by regulating the catecholamine/β2-AR/MACC1 signaling axis. Conversely, depression promotes the invasion and metastasis of GC by increasing catecholamine secretion. In addition, the chronic inflammatory state, immune dysfunction, intestinal microecological imbalance, and systemic dissemination of tumor metabolites caused by GC may directly or indirectly contribute to the pathological process of depression by activating the HPA axis and/or the sympathetic nervous system[38,39], regulating cortisol secretion[40], interfering with the synthesis and transmission of neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin and dopamine), and affecting the function of the brain-gut axis. Specifically, cells in patients with GC may release proinflammatory factors such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α[41]. Studies have shown that these factors are strongly associated with depression[42]. This may be because they penetrate the blood-brain barrier via the bloodstream, activate microglia, trigger neuroinflammatory responses, and damage hippocampal neurons. The hippocampus plays a critical role in emotion regulation, and its structural abnormalities directly increase the risk of depression. Moreover, intestinal flora imbalance and alterations in bacterial richness and diversity resulting from GC can modulate the tumor microenvironment and influence both GC development and the efficacy of immunotherapy[43]. GC is also significantly associated with tryptophan metabolism[44-46]. Disruptions in this pathway may impair the synthesis of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin), for which tryptophan is a biochemical precursor. Abnormal tryptophan metabolism significantly decreases central neurotransmitter levels and contributes to the onset of depression. In addition, malnutrition caused by GC, such as vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiencies, may impair the methylation pathway and interfere with myelin synthesis[47]. This process can exacerbate cognitive impairment and emotional instability, forming a vicious cycle of physical damage-neurological dysfunction-depression aggravation.

This minireview comprehensively examined the bidirectional relationship between depression and GC, revealing a complex interaction network involving neuroendocrine regulation, immune responses, metabolic disorders, and psychosocial factors. This finding not only provides a theoretical framework for understanding the comorbidity mechanisms of these two conditions but also offers important evidence for developing comprehensive intervention strategies in clinical practice. From the perspective of depression’s impact on GC, existing evidence clearly supports that chronic psychological stress activates the sympathetic nervous system and the HPA axis, thereby promoting the release of catecholamine neurotransmitters[48]. Through the β2-AR/MACC1 signaling axis, this process induces neuroendocrine phenotypic transformation and EMT in GC cells, ultimately accelerating tumor invasion and metastasis. The clinical study by Pan et al[19] confirmed that the severity of depression is positively correlated with serum catecholamine levels, MACC1 expression, and tumor-nodes-metastasis stage, providing direct evidence for the existence of a psychological-neuroendocrine-tumor axis. Furthermore, immune dysfunction associated with depression (such as Th1/Th17 imbalance) and the immunosuppression caused by chronically elevated cortisol further exacerbate the malignant transformation of the tumor microenvironment. Notably, the discovery that β2-AR agonists enhance chemotherapy resistance in GC cells through the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3-CD44 pathway suggests that patients with both GC and depression may require adjustments to treatment plans, and β2-AR-targeted therapy may represent a potential strategy for improving prognosis. Conversely, the effect of GC on depression involves both psychological and physiological factors. As a major stress event, GC impairs psychological resilience through disruptions in cognitive restructuring, manifesting as catastrophic thinking and crises of role identity. Compounding this, the long treatment course and prognostic uncertainty of GC further increase vulnerability to major depression. On a physiological level, chronic inflammation caused by GC, such as the release of proinflammatory factors including IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α[49], can penetrate the blood-brain barrier and activate neuroinflammatory responses, leading to hippocampal damage. Imbalance in the intestinal microecology reduces the synthesis of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) through disrupted tryptophan metabolism and, together with overactivation of the HPA axis, forms a vicious cycle of body-nerve-emotion. A meta-analysis by Kouhestani et al[5] showed that the prevalence of depression in patients with GC was 37%, significantly higher than in the general population. Moreover, in advanced cases, the triangular cycle of pain-sleep disorder-emotional deterioration is more prominent. This finding suggests that clinicians should identify and intervene in the impact of somatic symptoms on emotions at an early stage. The limitations of current research should also be noted. First, most of the existing understanding of underlying mechanisms originates from animal and cellular studies, and clinical translational evidence remains scarce. This gap is particularly evident in the lack of prospective cohort studies specifically designed to examine the association between depression and GC risk. Second, the molecular networks underlying their interaction remain incompletely elucidated.

For example, the mechanisms through which the brain-gut axis mediates bidirectional regulation via neurotransmitters, endocrine hormones, and immune factors warrant further investigation using multi-omics approaches. Third, current intervention studies predominantly examine isolated treatment strategies, often involving standalone psychological interventions such as reminiscence therapy or pharmacological monotherapies. However, they largely overlook integrated multimodal strategies that target the bidirectional pathophysiology linking depression and cancer. Future research should be advanced in three directions. First, large-scale prospective cohort studies are needed to clarify the risk factors for depression and GC incidence[50,51] and to explore heterogeneity in specific populations, such as elderly patients and those with advanced disease. Second, technologies such as single-cell sequencing and spatial transcriptomics should be employed to analyze the regulatory mechanisms of the catecholamine-immune-gut microbiota axis in the bidirectional interaction and to identify potential therapeutic targets. Third, randomized controlled trials should be designed to evaluate the effectiveness of a multidimensional strategy combining β2-AR antagonists, psychological intervention, and nutritional support in improving prognosis in patients with comorbidities. In clinical practice, an integrated process of screening-assessment-intervention should be established. For patients with GC, the PHQ-9 scale should be routinely used to screen for depressive symptoms. For patients with depression, enhanced monitoring of GC risk is warranted. In addition to the PHQ-9, other tools such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, Self-Rating Depression Scale, and structured clinical interviews can also be applied in clinical assessment. Following evidence-based practice, adopting a multimodal, integrated approach to intervention can maximize patient benefits. For instance, psychotherapeutic options may include cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy, both of which are applicable even for patients with advanced cancer. Pharmacological treatment may involve selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as sertraline and escitalopram, or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, such as venlafaxine and duloxetine. For patients with comorbidities, β-receptor blockers (e.g., propranolol) may be used to regulate proliferation and apoptosis[52], while cognitive behavioral therapy can improve psychological resilience, and vitamin B12 and folic acid supplementation can correct metabolic disorders. Only by breaking the vicious cycle between the two conditions can the goals of improving patient prognosis and quality of life be truly achieved. In conclusion, the bidirectional relationship between depression and GC represents a typical manifestation of the biopsychosocial medical model. In-depth research on its mechanisms and clinical translation may provide new breakthroughs at the intersection of oncology and psychiatry.

Current studies have begun to elucidate some mechanisms underlying their interaction, such as the catecholamine/β2-AR/MACC1 signaling axis and dysfunction of the brain-gut axis. However, the more detailed molecular mechanisms and regulatory networks remain to be fully explored. Future research should focus on identifying specific targets of this interaction to provide a foundation for developing more effective strategies for prevention and treatment. In clinical practice, attention should be given both to screening and intervention for depression in patients with GC and to monitoring GC risk in patients with depression. Through comprehensive biopsychosocial interventions, the vicious cycle between the two conditions can be disrupted, thereby improving treatment outcomes, prognosis, and quality of life.