Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i12.113289

Revised: September 30, 2025

Accepted: October 29, 2025

Published online: December 15, 2025

Processing time: 112 Days and 19.1 Hours

Recurrence remains the leading cause of poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), particularly among patients infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV). The telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter is the most fre

To evaluate the prognostic impact of TERT promoter mutations and efficiency of digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR).

A total of 66 HBV-related HCC patients who underwent hepatectomy were enrolled in this study. DNA extracted from fresh tumor tissues was analyzed for TERT promoter mutations using Sanger sequencing and dPCR. The dPCR assay was optimized by adding 7-deaza-dGTP, CviQ1, and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid to improve detection sensitivity. Concordance between methods was assessed, and nomogram survival prediction models were developed to evaluate prognostic value based on mutation status.

TERT promoter mutations were detected in 26/66 (39.39%) cases by Sanger sequencing and 30/66 (45.45%) by dPCR. The two methods showed high concordance (93.939%, κ = 0.876), with dPCR demonstrating 100% sensitivity and 90% specificity. Patients harboring TERT promoter mutations exhibited reduced overall survival and higher recurrence risk. Nomogram models successfully distinguished mutant from non-mutant cases for both overall survival (C-index: 0.7651) and disease-free survival (C-index: 0.6899).

TERT promoter mutation predicts poor prognosis in HBV-related HCC and serves as a biomarker for risk stratification. Optimized dPCR outperforms Sanger sequencing, and nomograms with TERT status guide precision therapy.

Core Tip: Telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutation is the most frequent genetic alteration in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma, yet its prognostic role remains uncertain. In this study, optimized digital polymerase chain reaction outperformed Sanger sequencing in detecting TERT promoter mutations. Patients with TERT mutations had significantly worse survival and higher recurrence risk after hepatectomy. Incorporating TERT mutation status into a nomogram model provides a practical tool for individualized prognosis prediction and may guide precision treatment in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Citation: Aizimuaji Z, Hu N, Li HY, Wang XJ, Ma S, Wang YR, Zheng RQ, Li Z, Zhao H, Rong WQ, Xiao T. Optimized digital polymerase chain reaction enables detection of telomerase reverse transcriptase C228T mutation for prognostic assessment in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(12): 113289

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i12/113289.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i12.113289

Primary liver cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide, with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounting for 75%-85% of cases, most often due to chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection[1]. Despite hepatectomy being the main curative treatment, HBV-related HCC shows high recurrence rates, significantly worsening prognosis[2]. Thus, identifying reliable biomarkers for recurrence is crucial to improve risk stratification and guide precision therapies. Somatic mutation detection is a central application of precision medicine[3]. In HCC, recurrent mutations frequently involve tumor protein p53, and catenin beta 1, and telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter, with the latter considered an early driver of tumorigenesis[4,5].

Telomerase, composed of TERT and telomerase RNA components, counteracts telomere shortening and is a well-recognized hallmark of carcinogenesis[5]. In HCC, telomerase activity is frequently reactivated through HBV X protein, HBV integration into the TERT promoter, or oncogene regulation[6]. Among these alterations, TERT promoter mutations occur in approximately 60% of cases, creating novel E-twenty-six transcription factor binding sites that enhance te

In recent years, nomograms have emerged as practical prognostic tools by integrating clinical and pathological variables into quantitative models, and several studies have shown they outperform conventional staging systems in predicting outcomes after liver resection[12]. Key factors such as albumin, bilirubin, microvascular invasion (MVI), tumor burden, and surgical variables have been incorporated, improving predictive accuracy and clinical utility[13]. More recently, radiomics has further advanced this field by extracting high-throughput features from computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging to capture tumor heterogeneity[14]. Radiomics-based nomograms, especially those using multiphase computed tomography, susceptibility-weighted imaging, or T2-weighted imaging, have demonstrated high accuracy in predicting MVI, early recurrence, and in stratifying patients for adjuvant therapies[15]. However, nomogram models incorporating molecular biomarkers such as TERT mutations are lacking, limiting the integration of genomic predictors into current prognostic tools.

TERT promoter mutations are among the most common genetic alterations in HCC and hold promise as prognostic biomarkers, yet their detection has been hindered due to the guanine-cytosine (GC)-rich promoter region[16-18]. While conventional gold standard Sanger sequencing has limited sensitivity, digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR) has recently emerged as a more reliable method for detecting TERT promoter mutations across cancers, including HCC[19]. In this study, we optimized a dPCR assay, established detection thresholds, and evaluated the prognostic value of the C228T mutation by developing nomogram-based survival prediction models in HBV-related HCC, aiming to integrate molecular and clinical predictors for precision treatment strategies.

This study included 66 HBV-related HCC patients who underwent hepatectomy at the Cancer Hospital of Peking Union Medical College and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences between January 2013 and May 2016, including 54 males and 12 females. The median diagnostic age of enrolled HBV-related HCC patients was 52 years (ranging from 46.25 to 59). We also collected fresh tumor tissue samples from the surgical specimens of these 66 patients and all the tissues were frozen immediately after surgery and stored at -80 °C. All patients had a clear postoperative pathological diagnosis by two expert pathologists and were confirmed to have HCC.

We collected patient information and biomarker test results, including cirrhosis and alcohol status, alpha fetoprotein (AFP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) retrospectively. Clinical data on the number of tumors, tumor diameter, liver capsule invasion (LCI), blood vessel invasion (BVI), Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, and MVI were also obtained from medical records. Patients were divided into the well-differentiated group (high, n = 10), moderately differentiated group (medium, n = 42), and poorly differentiated group (low, n = 14) according to histological grade using the criteria of Edmondson and Steiner[20]. Follow-up evaluations occurred in 2018 (first follow-up), 2019 (second follow-up), June 2021 (third follow-up), and August 2022 (fourth follow-up). The maximum follow-up time was 9.3 years.

An incubation solution containing 500 μL of DNA lysis solution was used to dissolve the frozen tissue samples [proteinase K 1 mg/mL, Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) 10 mmol/L, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (pH 8.0) 0.1 mol/L, sodium-dodecyl sulfate 0.5% (w/v)] at 55 °C, overnight. After digestion, DNA was extracted by phenol and chloroform, and stored at -20 °C until use. A Nanodrop spectrophotometer ND-1000 (Thermo Scientific, United States) was used to verify DNA concentration and quality. All DNA samples had an absorbance ratio equal to or above 1.80 at 260 nm and 280 nm.

We performed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reactions with genomic DNA in a 50 μL reaction mixture, with 2.5 μL of each primer, 0.25 μL HotStartTaq Plus DNA Polymerase (Qiagen, Germany), 10 μL Q-solution 5 × (Qiagen, Germany),

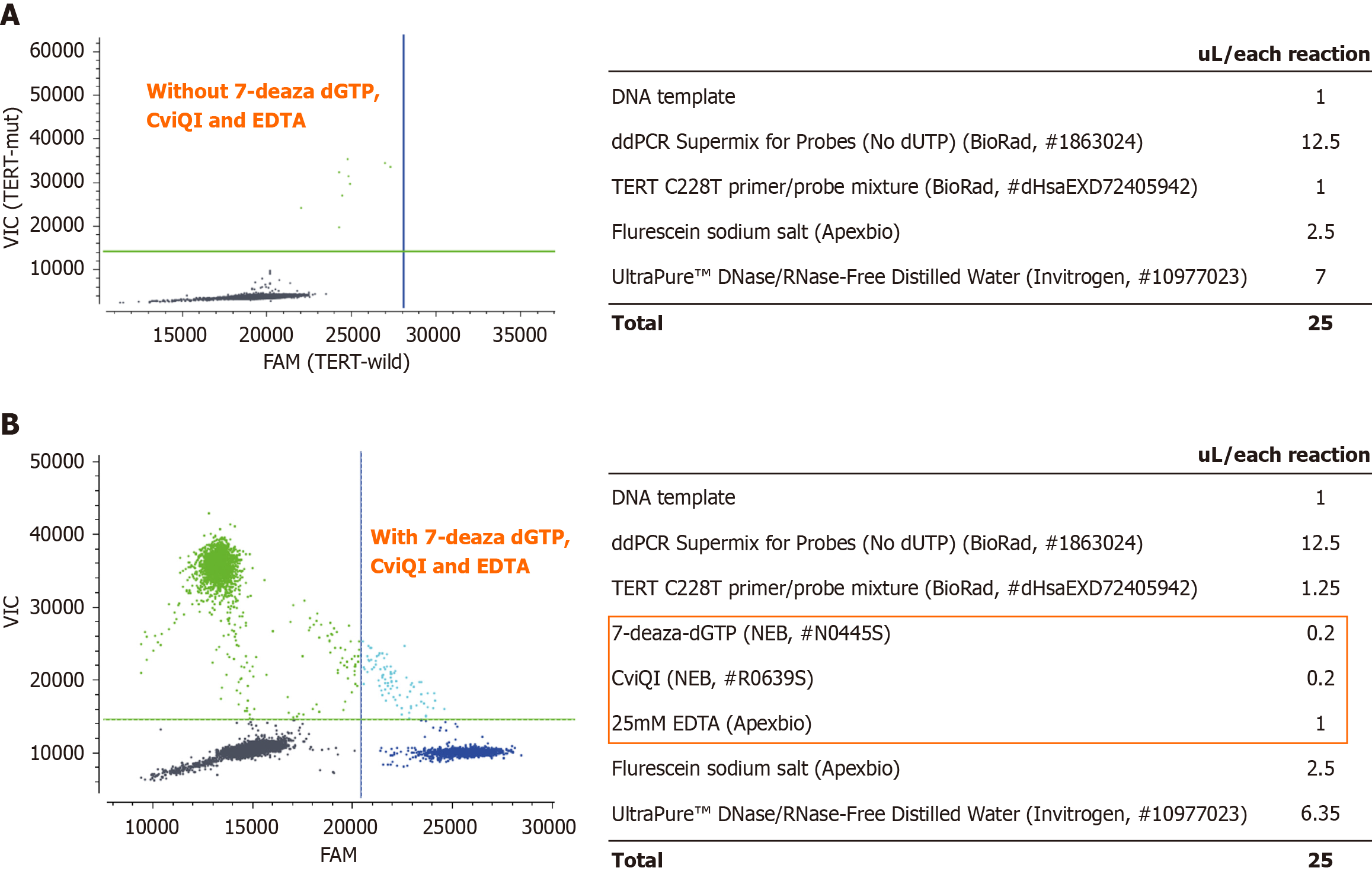

Our experimental conditions were verified on positive samples with known TERT promoter mutation. We performed the droplet generation process according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the Naica Crystal PCR system (Stilla Technologies, France). The reaction mixtures used in this assay were as follows: 12.5 μL ddPCR Supermix for Probes (no deoxyuridine triphosphate) (Bio-Rad, United States), 1.25 μL 20 × primer/probe mixture [TERT C228T_113 (dHsaEXD72405942), Bio-Rad, United States], restriction enzyme 0.2 μL (New England BioLabs; CviQI; R0639S, United States), 0.2 μL 7-Deaza-dGTP (New England BioLabs; N0445S, United States), 1 μL of 25 mmol/L EDTA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States), 2.5 μL of 10 μmol/L fluorescein sodium salt (Apexbio, United States), DNA template, and finally ultrapure DNAse/RNAse free H2O (Thermo Fisher Scientific/Gibco, United States) was added to a final volume of 25 μL. The cycling protocol was as follows: 1 cycle of 10 minutes at 37 °C, 1 cycle of 10 minutes at 95 °C, followed by 50 cycles of 95 °C for 30 seconds and 62 °C for 1 minutes, and a final hold at 4 °C (2 °C/seconds). The dPCR data were analyzed using Crystal Miner for the NaciaTM System v2.3.0 software (Stilla Technologies, France), and positive and negative controls were used to determine the thresholds for each mutation assay.

To ensure the detection quantity of TERT C228T mutations, we used mutation probes in the channel to determine a false positive measure and therefore detected a threshold for the smallest mutation droplet, twenty wild-type DNA samples for TERT mutations were tested by their respective dPCR. To determine the limit of blank (LoB), negative controls were analyzed, and background signals were obtained. At least five low-level (LL) samples were prepared independently (LL1, LL2, LL3, LL4, and LL5), and at least four replicates were performed per sample. We calculated the limit of detection (LoD) by determining the concentration of mutant alleles at which LL samples should comprise representative positive samples or representative matrix samples with a maximum target concentration of one to five times the calculated LoB. The LoB of TERT C228T was detected in pure wild-type samples in 0.35 cp/μL per well. The LoD of TERT C228T in LL samples was 0.55 cp/μL/well.

Our 66 HBV-related HCC cohort completed clinical and survival information, including, age, gender, ALT, AST, LDH, GGT, APTT, cirrhosis, alcohol, tumor number, tumor diameter, MVI, tumor differentiation, LCI, BVI, and BCLC grade. Cox regression analysis with univariate and multivariate variables was conducted to confirm that the predictions of the prognostic model were independent of clinical characteristics in HBV-related HCC.

Multivariable Cox models were used to calculate survival probability estimates for overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) nomograms. Up to 5 years after surgery, the accuracy of the nomogram models was evaluated based on Harrell’s C-index discrimination, calibration, and overall accuracy. To evaluate model performance, calibration and discrimination are commonly used methods, and they were calculated using a bootstrapping approach with 1000 resamples. Furthermore, C-index and time-dependent receiver operating characteristic analyses were also performed to compare predictive accuracies between the nomogram and prognostic variates separately. Additionally, to verify the clinical validity of the established nomogram, calibration curve analysis and decision curve analysis (DCA) were conducted.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were summarized using descriptive statistics. We performed χ2 or Fisher’s exact testing for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables to examine the causal relationship between clinicopathological factors and TERT mutation status (no vs yes). Based on Cohen’s kappa index, we evaluated the degree of agreement between dPCR and Sanger sequencing. Cohen proposed a categorical interpretation of the kappa index. Weak agreement ≤ 0, slight agreement is 0-0.2, moderate agreement is 0.21-0.40, average agreement is 0.41-0.60, and basic agreement is 0.61-0.80, while 0.81-1.00 was almost perfect. This index is considered too lenient for health-related research. Calculations for sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the TERT promoter mutations were performed using the Clopper-Pearson method. We performed Kaplan-Meier plots and Cox proportional hazards models using the R packages (v 3.6.3) “survminer” and “survival”. The OS was defined as the period from surgery until death due to any cause, and the DFS was the period after surgery until any recurrence or death. The nomograms for predicting the OS and DFS were generated using the R “rms” package. Other two-sided statistical tests were conducted, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the packages “survminer”, “rms”, “rmda”, and “timeROC” in R version 3.6.3.

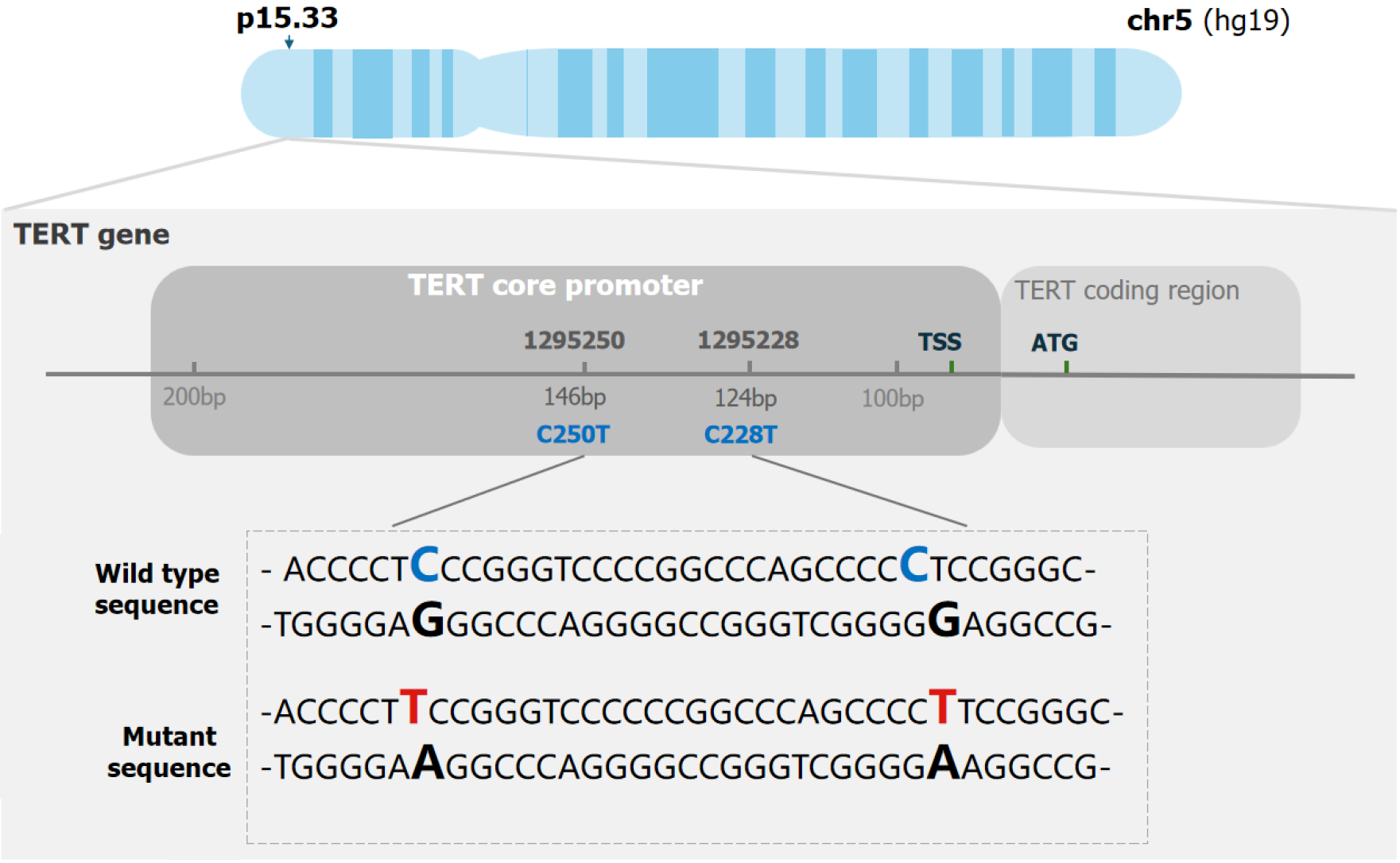

It was challenging to amplify the TERT promoter due to its high GC content (more than 80%) and the way it forms secondary structures, such as hairpin structures[22] (Figure 1). Thus, developing specific PCR assays for this region is challenging, posing a major obstacle to dPCR analysis with distinct droplet clustering. Therefore, to overcome the challenges presented by this issue, we planned to find suitable additives to accurately detect variants of the TERT promoter region using dPCR. In previous studies, 7-deaza-dGTP has been shown to improve cluster resolution in dPCR in agreement with Colebatch et al[23]. CviQ1 was added to a dye-binding detection assay to increase cluster tightness[24]. An EDTA titration was performed to determine the applicable Mg2+ concentration in the PCR mixture. We conducted the assays with or without these additives in the PCR reactions and found a suitable concentration of these chemical additives. As a result, droplet clusters were separated in patient HC2873 after we optimized the assays. It was also necessary to vary amplification parameters and additives so that cluster separation and tightness could be maximized. The detailed amount of each reagent is shown in Figure 2.

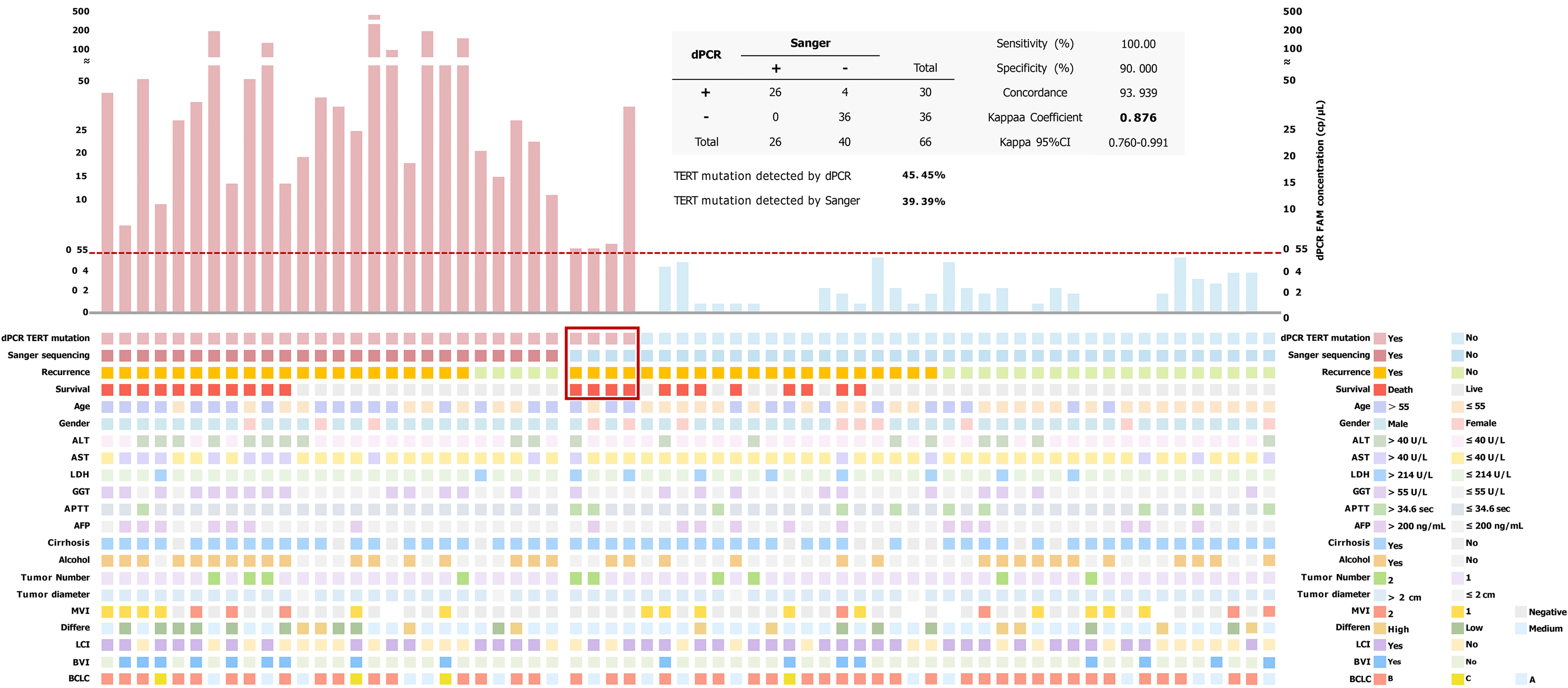

An orthogonal method, such as Sanger sequencing, was used to validate the specificity of the optimized assays on mutant templates. We measured the sensitivity of the assay by serially diluting wild-type genomic DNA into TERT promoter mutant genomic DNA. We established the LoB from 20 replicate wells of tumor samples from the patient who did not have TERT mutation in his biopsy tissue. The LoB for the C228T was 0.35 cp/μL. LoD, the lowest frequency of TERT C228T that can be accurately distinguished from five independent LL samples (each level performing four replicates) was found to be 0.55 cp/μL/well, as shown in Supplementary Table 1. Thirty out of 66 cases (45.45%) had 6-carboxyfluorescein concentrations higher than 0.55 cp/μL (LoD), which were treated as positive for TERT C228T promoter mutations in HCC cohort samples detected by dPCR (Figure 3).

In our study, 66 HBV-related HCC patients who underwent hepatectomy were enrolled. All patients had HBV infection. Cirrhosis was present in 55 patients (83.3%). Ten patients (15.2%) had multiple malignant tumor foci. The patients were staged according to the BCLC classification. Seventeen patients (25.8%) had early HCC (BCLC A), 45 (68.2%) had intermediate HCC (BCLC B), and 4 (6.1%) had advanced (BCLC C). Most patients had HCC related to chronic alcohol abuse (n = 34, 51.5%). This included 38 cases with LCI and 17 with the BVI. Regarding tumor differentiation, the majority of tumors were moderately differentiated (n = 42, 63.6%), 21.2% were poorly differentiated (n = 14), and the remaining 15.2% (n = 10) were well differentiated. Elevated AFP (> 200 ng/mL) was seen in 19 patients (28.8%). These patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Survival | Recurrence | ||||

| Live, n = 44 | Death, n = 22 | P value | No, n = 24 | Yes, n = 42 | P value | |

| Age | 0.432 | 0.080 | ||||

| ≤ 55 | 26 (59.1) | 10 (45.5) | 17 (70.8) | 19 (45.2) | ||

| > 55 | 18 (40.9) | 12 (54.5) | 7 (29.2) | 23 (54.8) | ||

| Gender | 0.193 | 0.512 | ||||

| Male | 38 (86.4) | 16 (72.7) | 21 (87.5) | 33 (78.6) | ||

| Female | 6 (13.6) | 6 (27.3) | 3 (12.5) | 9 (21.4) | ||

| ALT | 0.501 | 0.817 | ||||

| ≤ 40 U/L | 33 (75.0) | 14 (63.6) | 18 (75.0) | 29 (69.0) | ||

| > 40 U/L | 11 (25.0) | 8 (36.4) | 6 (25.0) | 13 (31.0) | ||

| AST | 0.117 | 0.560 | ||||

| ≤ 40 U/L | 37 (84.1) | 14 (63.6) | 20 (83.3) | 31 (73.8) | ||

| > 40 U/L | 7 (15.9) | 8 (36.4) | 4 (16.7) | 11 (26.2) | ||

| LDH | 0.281 | 0.736 | ||||

| ≤ 214 U/L | 39 (88.6) | 17 (77.3) | 21 (87.5) | 35 (83.3) | ||

| > 214 U/L | 5 (11.4) | 5 (22.7) | 3 (12.5) | 7 (16.7) | ||

| GGT | 0.025a | 0.058 | ||||

| ≤ 55 U/L | 32 (72.7) | 9 (40.9) | 19 (79.2) | 22 (52.4) | ||

| > 55 U/L | 12 (27.3) | 13 (59.1) | 5 (20.8) | 20 (47.6) | ||

| APTT | 1.000 | 0.511 | ||||

| ≤ 34.6 seconds | 37 (84.1) | 18 (81.8) | 19 (79.2) | 36 (85.7) | ||

| > 34.6 seconds | 7 (15.9) | 4 (18.2) | 5 (20.8) | 6 (14.3) | ||

| AFP | 0.003a | 0.817 | ||||

| ≤ 200 ng/mL | 37 (84.1) | 10 (45.5) | 18 (75.0) | 29 (69.0) | ||

| > 200 ng/mL | 7 (15.9) | 12 (54.5) | 6 (25.0) | 13 (31.0) | ||

| Cirrhosis | 0.739 | 0.733 | ||||

| No | 8 (18.2) | 3 (13.6) | 3 (12.5) | 8 (19.0) | ||

| Yes | 36 (81.8) | 19 (86.4) | 21 (87.5) | 34 (81.0) | ||

| Alcohol | 0.258 | 0.561 | ||||

| No | 24 (54.5) | 8 (36.4) | 10 (41.7) | 22 (52.4) | ||

| Yes | 20 (45.5) | 14 (63.6) | 14 (58.3) | 20 (47.6) | ||

| Tumor number | 0.720 | 0.306 | ||||

| Single | 38 (86.4) | 18 (81.8) | 22 (91.7) | 34 (81.0) | ||

| Multiple | 6 (13.6) | 4 (18.2) | 2 (8.3) | 8 (19.0) | ||

| Tumor diameter | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| ≤ 2 cm | 3 (6.8) | 1 (4.5) | 1 (4.2) | 3 (7.1) | ||

| > 2 cm | 41 (93.2) | 21 (95.5) | 23 (95.8) | 39 (92.9) | ||

| MVI1 | 0.052 | 0.722 | ||||

| Negative | 30 (75.0) | 10 (45.5) | 15 (68.2) | 25 (62.5) | ||

| 1 | 7 (17.5) | 8 (36.4) | 4 (18.2) | 11 (27.5) | ||

| 2 | 3 (7.5) | 4 (18.2) | 3 (13.6) | 4 (10.0) | ||

| Differe | 0.132 | 0.322 | ||||

| High | 9 (20.5) | 1 (4.5) | 5 (20.8) | 5 (11.9) | ||

| Medium | 28 (63.6) | 14 (63.6) | 16 (66.7) | 26 (61.9) | ||

| Low | 7 (15.9) | 7 (31.8) | 3 (12.5) | 11 (26.2) | ||

| LCI | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| No | 19 (43.2) | 9 (40.9) | 10 (41.7) | 18 (42.9) | ||

| Yes | 25 (56.8) | 13 (59.1) | 14 (58.3) | 24 (57.1) | ||

| BVI | 0.022a | 0.325 | ||||

| No | 37 (84.1) | 12 (54.5) | 20 (83.3) | 29 (69.0) | ||

| Yes | 7 (15.9) | 10 (45.5) | 4 (16.7) | 13 (31.0) | ||

| BCLC | 0.551 | 0.388 | ||||

| A | 13 (29.5) | 4 (18.2) | 7 (29.2) | 10 (23.8) | ||

| B | 29 (66.0) | 16 (72.7) | 17 (70.8) | 28 (66.7) | ||

| C | 2 (4.5) | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (9.5) | ||

| Digital polymerase chain reaction TERT mutation | 0.066 | 0.005a | ||||

| No | 28 (63.6) | 8 (36.4) | 19 (79.2) | 17 (40.5) | ||

| Yes | 16 (36.4) | 14 (63.6) | 5 (20.8) | 25 (59.5) | ||

| Sanger TERT mutation | 0.786 | 0.038a | ||||

| No | 28 (63.6) | 13 (54.5) | 19 (79.2) | 21 (50.0) | ||

| Yes | 16 (36.4) | 9 (45.5) | 5 (20.8) | 21 (50.0) | ||

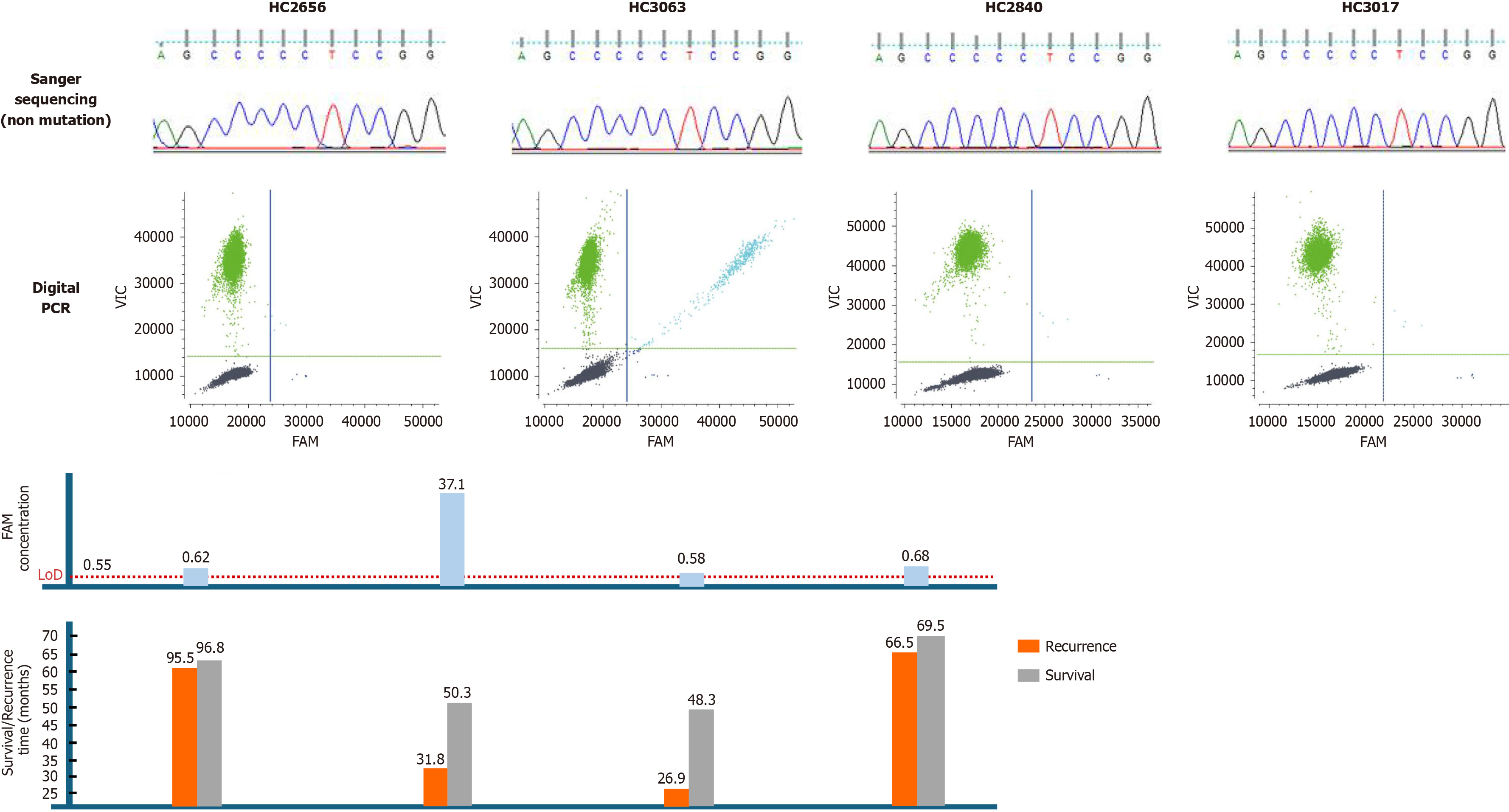

Correlations between TERT promoter mutation status and clinicopathological variables in Sanger sequencing and dPCR are shown in Figure 3. 26 cases were examined for TERT C228T mutation by both Sanger sequencing and dPCR. However, 4 patients were positive for C228T by dPCR assay but negative by Sanger sequencing. The in-depth sequencing results of these 4 samples (all dPCR positive, but Sanger negative) associated with 6-carboxyfluorescein concentration and prognostic status were examined (Figure 4).

We further analyzed the relationship between the TERT C228T mutation and clinicopathological features (Sup

Sanger sequencing found that 39.39% (26/66) were positive, whereas dPCR found that 45.45% (30/66) were positive. The consistency of the two methods for detecting TERT C228T was good (concordance = 93.939). The Cohen’s kappa coefficient was 0.876 (95% confidence interval: 0.760-0.991) suggesting perfect agreement. While Sanger sequencing is regarded as the gold standard for detecting sequence variation, dPCR offers improved sensitivity over Sanger sequencing. By dPCR, TERT C228T mutation was detected with 100% sensitivity and 90% specificity, respectively (Figure 3). Therefore, in the next analysis we decided to choose the TERT mutation status detected by dPCR.

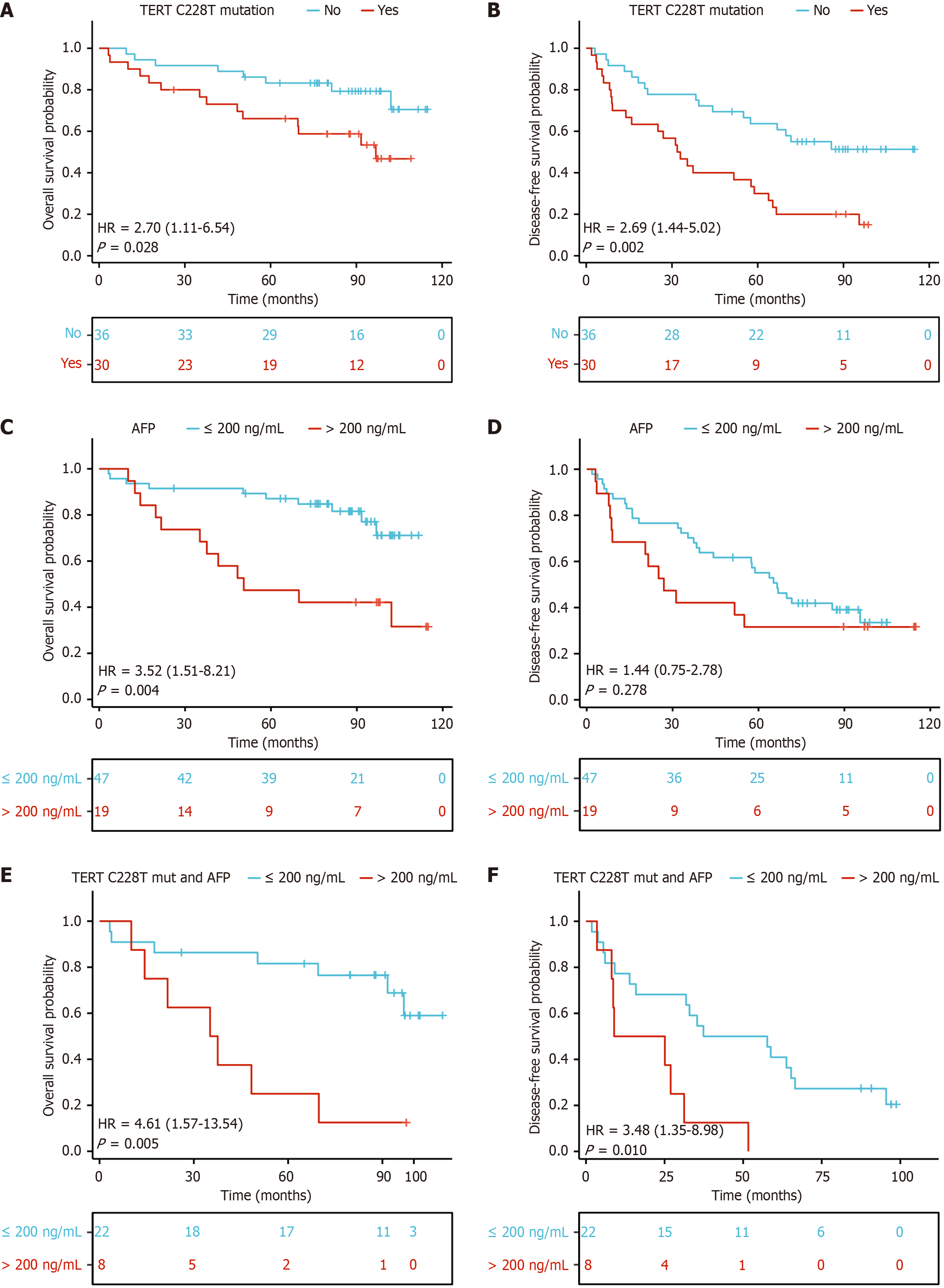

Tumor recurrence rates were 59.5% vs 50% in TERT C228T positive patients detected by dPCR vs Sanger sequencing (Table 1). Among those with available data, there was a significant correlation between tumor recurrence in the presence of the TERT C228T mutation detected by dPCR (P < 0.01). There were no significant correlations between tumor recurrence status and age, cirrhosis, AFP level, alcohol, or other clinical variables (Table 1). Kaplan-Meier analysis of the differences in OS and DFS in the study with and without TERT promoter mutations are shown in Figure 5. Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed significantly shorter OS (Figure 5A) and DFS (Figure 5B) in HBV-related HCC patients with TERT C228T mutation than in those without mutation. DFS was not significantly different between patients with AFP > 200 ng/mL and AFP ≤ 200 ng/mL, but was significantly different in terms of OS (Figure 5C and D). In all TERT C228T mutated patients, significant differences were found between those with AFP > 200 ng/mL and those with AFP ≤ 200 ng/mL in both OS (Figure 5E) and DFS (Figure 5F) (OS: P = 0.005, DFS: P = 0.01).

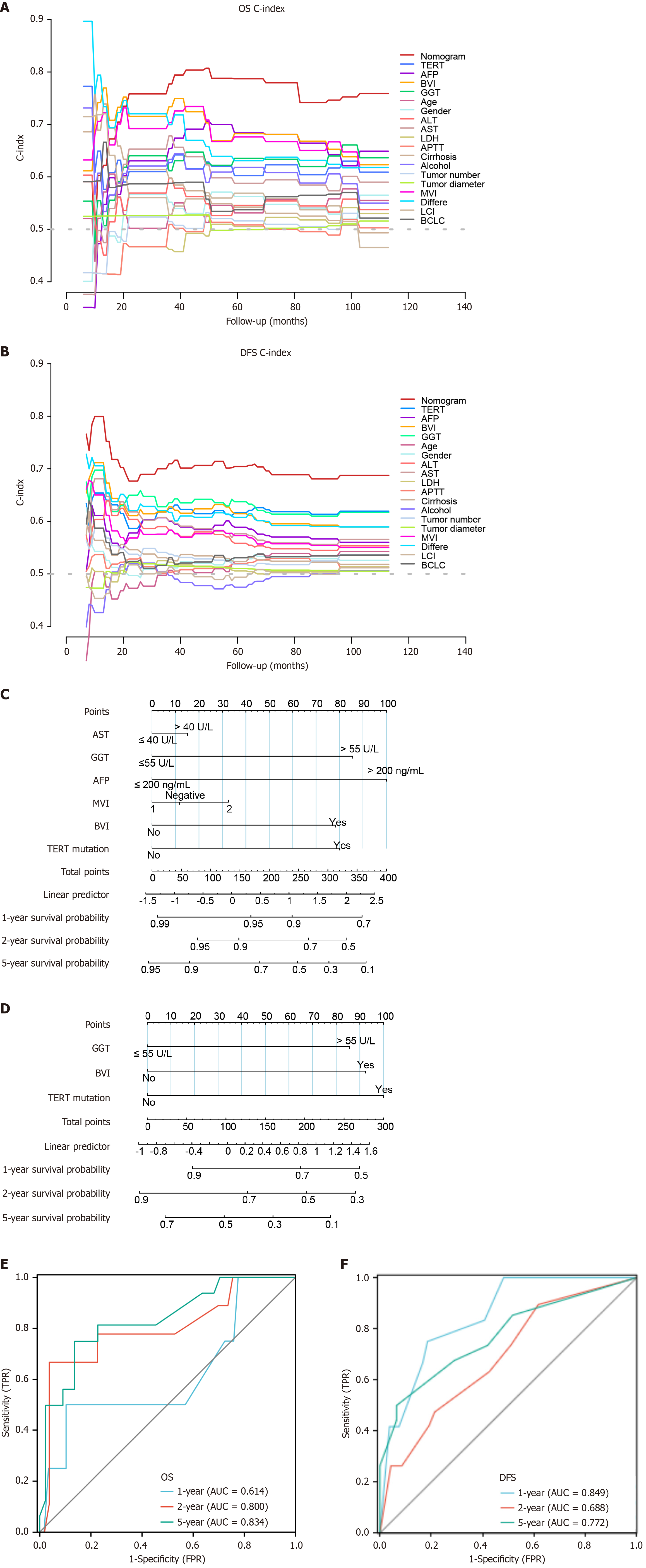

We performed univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses to examine whether TERT mutations in our HCC cohort were independent of other clinical variables. Following univariate Cox regression analysis significant variables (P < 0.05) were selected for multivariate Cox regression analysis. The univariate analysis determined five parameters that were slightly or significantly associated with OS: TERT mutation status, AST, GGT, AFP, BVI and MVI were slightly associated with OS (Table 2). Following multivariate Cox regression analysis TERT mutation status, GGT and BVI, significantly and independently determined DFS (Table 2). In addition, the C-index was also compared in the nomograms for OS and DFS, TERT mutation and 18 clinical characteristics. The nomograms successfully differentiated TERT C228T mutant and non-mutant patients with HBV-related HCC associated with OS and DFS (Figure 6A and B). Overall, these results showed that TERT mutations consistently outperformed conventional clinical characteristics in survival prediction.

| Characteristics | OS, univariate analysis | OS, multivariate analysis | DFS, univariate analysis | DFS, multivariate analysis | ||||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age (> 55/≤ 55) | 0.65 (0.28-1.50) | 0.311 | 0.64 (0.35-1.18) | 0.149 | ||||

| Gender (female/male) | 1.81 (0.71-4.64) | 0.214 | 1.43 (0.68-3.00) | 0.341 | ||||

| ALT (≤ 40/> 40 U/L) | 1.70 (0.71-4.05) | 0.235 | 1.45 (0.76-2.80) | 0.264 | ||||

| AST (≤ 40/> 40 U/L) | 2.84 (1.17-6.90) | 0.021a | 1.17 (0.42-3.24) | 0.766 | 1.70 (0.85-3.39) | 0.132 | ||

| LDH (≤ 214/> 214 U/L) | 1.71 (0.63-4.63) | 0.295 | 1.22 (0.54-2.74) | 0.639 | ||||

| GGT (≤ 55/> 55 U/L) | 3.40 (1.43-8.10) | 0.006a | 2.40 (0.88-6.54) | 0.087 | 2.53 (1.37-4.68) | 0.003a | 2.14 (1.13-4.05) | 0.019a |

| APTT (> 34.6 seconds/≤ 34.6 seconds) | 0.99 (0.33-2.93) | 0.984 | 1.45 (0.61-3.46) | 0.398 | ||||

| AFP (> 200/≤ 200 ng/mL) | 0.28 (0.12-0.66) | 0.004a | 0.36 (0.13-0.98) | 0.044a | 0.91 (0.49-1.68) | 0.756 | ||

| Cirrhosis (yes/no) | 0.85 (0.25-2.86) | 0.788 | 1.41 (0.65-3.06) | 0.380 | ||||

| Alcohol (no/yes) | 2.13 (0.89-5.11) | 0.090 | 0.93 (0.51-1.70) | 0.806 | ||||

| Tumor number (single/multiple) | 1.46 (0.49-4.33) | 0.495 | 1.61 (0.75-3.49) | 0.224 | ||||

| Tumor diameter (> 2 cm/≤ 2 cm) | 0.62 (0.08-4.64) | 0.644 | 1.44 (0.44-4.68) | 0.545 | ||||

| MVI | 0.038a | 0.634 | ||||||

| Negative | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 2 | 3.58 (1.11-11.53) | 0.032a | 1.24 (0.22-6.84) | 0.806 | 1.25 (0.43-3.59) | 0.683 | ||

| 1 | 2.68 (1.05-6.82) | 0.038a | 0.89 (0.20-4.04) | 0.877 | 1.40 (0.69-2.86) | 0.353 | ||

| Differe | 0.086 | 0.086 | ||||||

| Medium | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| High | 0.27 (0.04-2.08) | 0.210 | 0.74(0.29-1.94) | 0.544 | ||||

| Low | 2.14 (0.85-5.37) | 0.105 | 2.02 (1.00-4.11) | 0.052 | ||||

| LCI (yes/no) | 0.97 (0.41-2.29) | 0.948 | 1.08 (0.59-2.01) | 0.797 | ||||

| BVI (no/yes) | 4.36 (1.82-10.43) | < 0.001a | 2.23 (0.50-9.84) | 0.292 | 2.19 (1.13-4.23) | 0.020a | 2.27 (1.15-4.50) | 0.018a |

| BCLC | 0.230 | 0.096 | ||||||

| A | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| B | 1.66 (0.55-4.97) | 0.365 | 2.50 (1.01-6.14) | 0.047a | ||||

| C | 2.64 (0.48-14.53) | 0.264 | 1.67 (0.75-3.72) | 0.206 | ||||

| TERT mutation (no/yes) | 2.70 (1.12-6.54) | 0.028a | 2.27 (0.84-6.14) | 0.107 | 2.69 (1.45-5.02) | 0.002a | 2.43 (1.28-4.63) | 0.007a |

Based on the final multivariable model, the nomogram was developed to predict survival at 1-year, 2-years, 5-years and recurrence based on risk factors in HBV-related HCC patients who underwent hepatectomy. The total score was 0-100 and 0-300, respectively, and each variable was calculated and merged. A high score indicates a high risk of death and recurrence in relation to OS and DFS, respectively (Figure 6C and D). For example, an HBV-related HCC patient with TERT mutation (100 points) GGT > 55 U/L (86 points), and without BVI (0 points) had a total score of 186 points. The 1-year recurrence probability was 71%. Compared with other clinical information, TERT mutations contributed most to the risk score (0 to 100), based on Cox multiple regression results. The inclusion of TERT mutation status improved the predictive accuracy of both OS and DFS nomograms. The OS and DFS models incorporating TERT mutation had maximum C-index values of 0.7651 and 0.6899, respectively, compared to 0.7498 and 0.6492 for models excluding TERT mutation. These findings underscore the significant contribution of TERT mutation in predicting prognosis in HBV-related HCC patients after hepatectomy (Supplementary Figure 1).

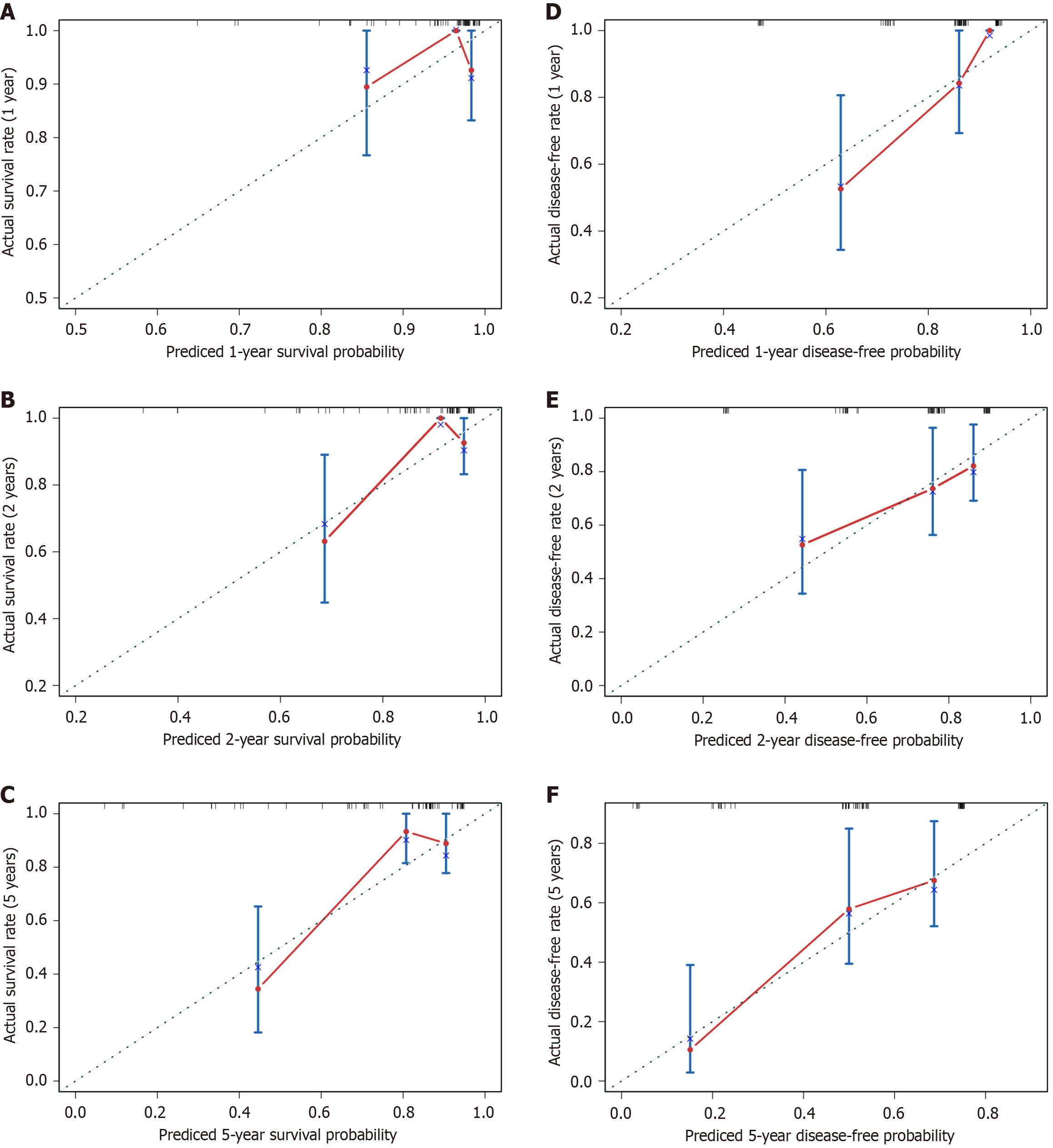

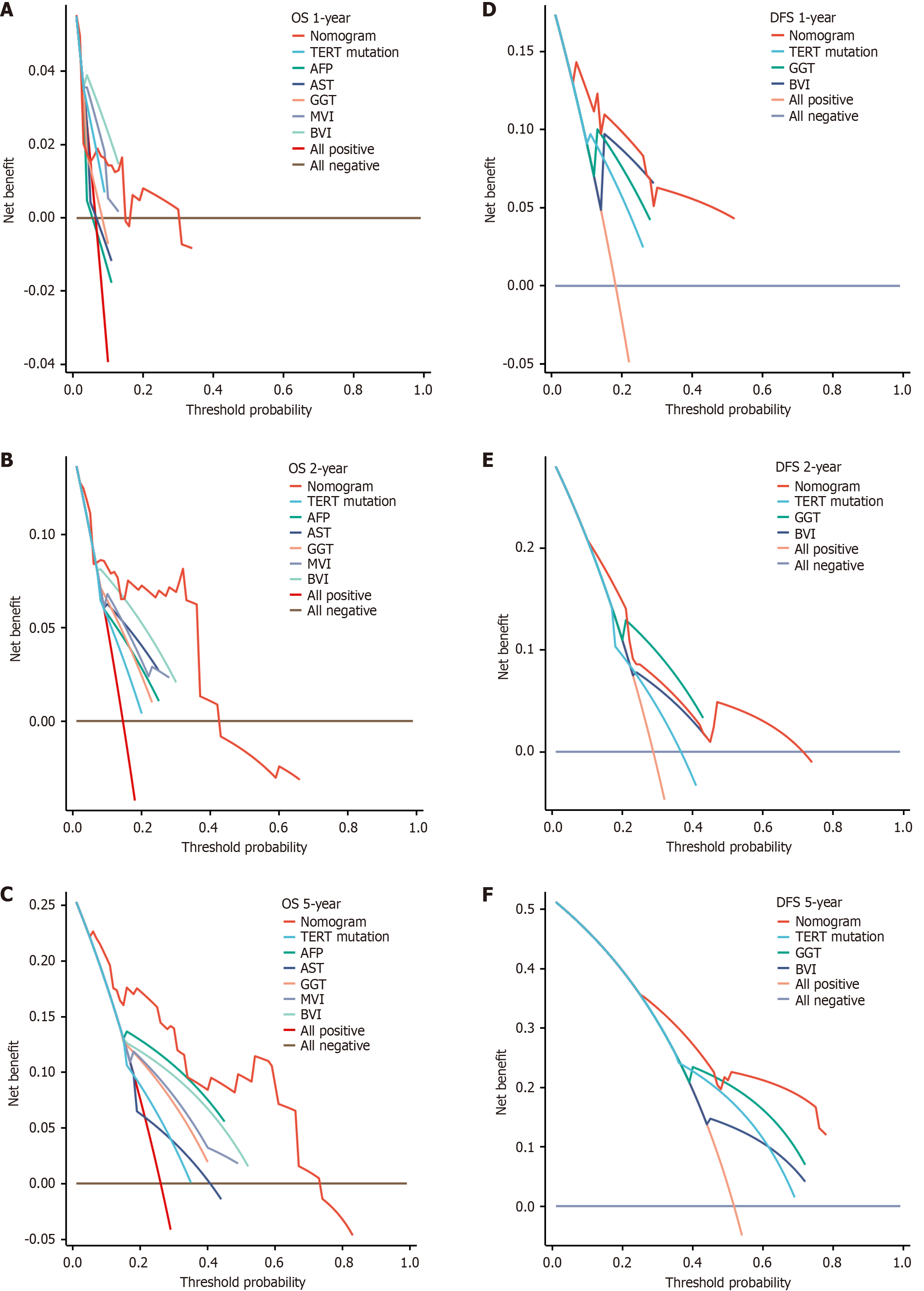

Areas under the curve for OS at 1-year, 2-years, and 5-years follow-up were 0.614, 0.800, and 0.834, respectively (Figure 6E). Areas under the curve for DFS at 1-year, 2-years, and 5-years follow-up were 0.849, 0.688 and 0.772, respectively. The models’ performance was evaluated by calibration and discrimination (Figure 6F). Nomogram predictions are represented on the X-axis, and actual survival and recurrence probabilities are displayed on the Y-axis. An ideal curve was a 45° line, indicating good agreement between prediction and observation. Calibration curves for OS and DFS were plotted at 1-year, 2-year, and 5-year intervals, revealing consistent results between predicted and observed data. (OS: Figure 7A-C; DFS: Figure 7D-F). Based on the results of our study, we found that particularly in the 5-year prediction, the performance of nomograms plotted as solid lines were satisfactory (Figure 7C and F). A DCA was used to determine whether the models could guide treatment in our HBV-related HCC cohort. Additionally, high predictive efficiency of the nomogram was observed for OS and DFS in HBV-related HCC patients after hepatectomy, based on DCA curves at 1-year, 2-years, and 5-years (OS: Figure 8A-C; DFS: Figure 8D-F). Overall, the nomogram predicted whether HBV-related HCC patients would relapse after hepatectomy more accurately than individual prognostic factors.

In hepatocarcinogenesis, TERT promoter mutation is recognized as an early event. Somatic mutation status, particularly TERT mutations, has been associated with poor prognosis and is considered a potential predictor of liver cancer outcomes[9]. However, the GC-rich region of the TERT promoter hampers amplification efficiency, reducing assay performance[17]. To address this, we employed dPCR to achieve more accurate detection of TERT promoter variants.

With its high sensitivity, precision, and ability to provide absolute quantification without a standard curve, dPCR has been widely applied to detect pathogens and somatic mutations[25]. In our study, after optimizing the assay, dPCR demonstrated high concordance, sensitivity, and specificity compared with Sanger sequencing when detecting DNA from fresh HBV-related HCC tumor tissues. Notably, all patients who tested positive for the TERT C228T mutation by dPCR but negative by Sanger sequencing experienced postoperative recurrence and subsequently died during follow-up. Some of these cases were only slightly above the detection threshold (LoD 0.55 cp/μL), underscoring the importance of carefully defining this cutoff. These findings highlight the superiority of dPCR in detecting GC-rich TERT promoter mutations, and its potential to provide stronger prognostic information. Previous studies comparing the two methods yielded unsatisfactory results[26], possibly due to limited postoperative follow-up data, which may have underestimated the prognostic relevance of TERT mutations. In this study, TERT C228T mutation was enriched in patients older than 55 years, suggesting an age-related accumulation of somatic mutational burden or selective retention under chronic liver injury and replicative stress. Mutation-positive cases showed a higher proportion of poor differentiation, implying a potential role in tumor dedifferentiation. Trends toward association with elevated AST, GGT, and heavy alcohol consumption suggest links with chronic hepatic inflammation and metabolic stress. Given the limited sample size and statistical power, future studies with larger cohorts, multivariate analyses, and survival evaluation are warranted to clarify the biological and prognostic significance of TERT C228T mutation in HCC.

Furthermore, Jang et al[27] reported that TERT promoter mutations detected in resected HCC tissues were significantly correlated with survival but not with recurrence. Another study found that TERT promoter mutations alone were not independently associated with overall or recurrence-free survival; however, when combined with single nucleotide polymorphism rs2853669, they were linked to poorer outcomes[28]. In contrast, our HBV-related HCC cohort demon

To further validate the prognostic value of TERT promoter mutations, we constructed a nomogram to predict outcomes in HBV-related HCC patients after hepatectomy. Our findings suggest that detection of the TERT C228T mutation by dPCR improves recurrence prediction and should be considered alongside clinical variables such as AST, GGT, AFP, MVI, and BVI for OS, and GGT, BVI, and TERT C228T for DFS. Calibration curves demonstrated good agreement between predicted and observed outcomes at 1-, 2-, and 5-year intervals. This model provides complementary insights into tumor biology and enables patient-specific risk stratification. Notably, Zhu et al[38] reported that patients with TERT mutations may benefit from atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable HCC, further highlighting its clinical relevance. With continued validation in larger cohorts, this nomogram may serve as a valuable tool to guide precision management in HBV-related HCC.

Several limitations in this study should be acknowledged. First, this study was constrained by a relatively small sample size and the absence of validation in a large-scale cohort, which may have introduced selection bias. Second, the lack of a randomized control group represents another major limitation, partly due to the low incidence of non-HBV-related HCC in our center. Third, the findings may be influenced by epidemiological differences in HBV-related HCC across race, ethnicity, and region, as well as variations in surgical techniques and indications among institutions.

In summary, we optimized a dPCR assay and established detection thresholds, demonstrating that this highly sensitive and specific method identifies HBV-related HCC patients at higher risk of recurrence more effectively than Sanger sequencing. This study is the first to develop nomogram models incorporating TERT mutation status to validate its prognostic value in HBV-related HCC, while also highlighting the clinical utility of dPCR for somatic mutation detection. Nonetheless, larger multicenter and prospective studies are needed to confirm the reliability of this model. Our findings may provide a useful reference for precision treatment strategies in HBV-related HCC and contribute to precision oncology. Moreover, extending this approach to diverse sample types, including circulating tumor DNA from liquid biopsy, may enhance postoperative monitoring and broaden its applicability to other cancers such as urothelial carcinoma.

In this study, we optimized a highly sensitive and specific dPCR assay for detecting TERT promoter mutations in HBV-related HCC patients and demonstrated its superiority over conventional Sanger sequencing. We established and validated the first nomogram models incorporating TERT mutation status to predict recurrence risk, highlighting its potential clinical utility for precision treatment strategies.

The authors are grateful not only to the consent of patients and their family members, but also the investigators and research staff involved.

| 1. | Yeo YH, Abdelmalek M, Khan S, Moylan CA, Rodriquez L, Villanueva A, Yang JD. Current and emerging strategies for the prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;22:173-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Peng H, Lei SY, Fan W, Dai Y, Zhang Y, Chen G, Xiong TT, Liu TZ, Huang Y, Wang XF, Xu JH, Luo XH. Assessing recent recurrence after hepatectomy for hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma by a predictive model based on sarcopenia. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:1727-1738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Farhat J, Alzyoud L, AlWahsh M, Acharjee A, Al-Omari B. Advancing Precision Medicine: The Role of Genetic Testing and Sequencing Technologies in Identifying Biological Markers for Rare Cancers. Cancer Med. 2025;14:e70853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li J, Bai L, Xin Z, Song J, Chen H, Song X, Zhou J. TERT-TP53 mutations: a novel biomarker pair for hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence and prognosis. Sci Rep. 2025;15:3620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Terra ML, Sant'Anna TBF, de Barros JJF, de Araujo NM. Geographic and Viral Etiology Patterns of TERT Promoter and CTNNB1 Exon 3 Mutations in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:2889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bonelli P, Tornesello AL, Tuccillo FM, Starita N, Cerasuolo A, Cimmino TP, Amiranda S, Izzo F, Ferrara G, Buonaguro L, De Re V, Buonaguro FM, Tornesello ML. HCV-related hepatocellular carcinoma: gene signatures associated with TERT promoter mutations and sex. J Transl Med. 2025;23:639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sant'Anna TBF, Terra ML, de Barros JJF, Ruivo LAS, Fernandes A, Begnami MDFS, Pannain VLN, Campos AHJFM, Moreira ODC, de Araujo NM. High Prevalence of TERT and CTNNB1 Mutations in Brazilian HCC Tissues: Insights into Early Detection and Risk Stratification. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:6503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen L, Li W, Zai W, Zheng X, Meng X, Yao Q, Li W, Liang Y, Ye M, Zhou K, Liu M, Yang Z, Mao Z, Wei H, Yang S, Shi G, Yuan Z, Yu W. HBV sequence integrated to enhancer acting as oncogenic driver epigenetically promotes hepatocellular carcinoma development. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2025;44:155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim JS, Kim HS, Tak KY, Han JW, Nam H, Sung PS, Lee SW, Kwon JH, Bae SH, Choi JY, Yoon SK, Jang JW. Male preference for TERT alterations and HBV integration in young-age HBV-related HCC: implications for sex disparity. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2025;31:509-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mishima M, Takai A, Takeda H, Iguchi E, Nakano S, Fujii Y, Ueno M, Ito T, Teramura M, Eso Y, Shimizu T, Maruno T, Hidema S, Nishimori K, Marusawa H, Hatano E, Seno H. TERT upregulation promotes cell proliferation via degradation of p21 and increases carcinogenic potential. J Pathol. 2024;264:318-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | He L, Zhang X, Zhang S, Wang Y, Hu W, Li J, Liu Y, Liao Y, Peng X, Li J, Zhao H, Wang L, Lv YF, Hu CJ, Yang SM. H. Pylori-Facilitated TERT/Wnt/β-Catenin Triggers Spasmolytic Polypeptide-Expressing Metaplasia and Oxyntic Atrophy. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025;12:e2401227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zeng J, Chen G, Zeng J, Liu J, Zeng Y. Development of nomograms to predict outcomes for large hepatocellular carcinoma after liver resection. Hepatol Int. 2025;19:428-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tian Y, Wang Y, Wen N, Lin Y, Liu G, Li B. Development and validation of nomogram to predict overall survival and disease-free survival after surgical resection in elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1395740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang G, Ding F, Chen K, Liang Z, Han P, Wang L, Cui F, Zhu Q, Cheng Z, Chen X, Huang C, Cheng H, Wang X, Zhao X. CT-based radiomics nomogram to predict proliferative hepatocellular carcinoma and explore the tumor microenvironment. J Transl Med. 2024;22:683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Geng Z, Wang S, Ma L, Zhang C, Guan Z, Zhang Y, Yin S, Lian S, Xie C. Prediction of microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with MRI radiomics based on susceptibility weighted imaging and T2-weighted imaging. Radiol Med. 2024;129:1130-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lyu X, Sze KM, Lee JM, Husain A, Tian L, Imbeaud S, Zucman-Rossi J, Ng IO, Ho DW. Disparity landscapes of viral-induced structural variations in HCC: Mechanistic characterization and functional implications. Hepatology. 2025;81:1805-1821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kovács Á, Sükösd F, Kuthi L, Boros IM, Vedelek B. Novel method for detecting frequent TERT promoter hot spot mutations in bladder cancer samples. Clin Exp Med. 2024;24:192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Li HY, Zheng LL, Hu N, Wang ZH, Tao CC, Wang YR, Liu Y, Aizimuaji Z, Wang HW, Zheng RQ, Xiao T, Rong WQ. Telomerase-related advances in hepatocellular carcinoma: A bibliometric and visual analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:1224-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 19. | Li H, Li J, Zhang Z, Yang Q, Du H, Dong Q, Guo Z, Yao J, Li S, Li D, Pang N, Li C, Zhang W, Zhou L. Digital Quantitative Detection for Heterogeneous Protein and mRNA Expression Patterns in Circulating Tumor Cells. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025;12:e2410120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Edmondson HA, Steiner PE. Primary carcinoma of the liver: a study of 100 cases among 48,900 necropsies. Cancer. 1954;7:462-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kwa WT, Effendi K, Yamazaki K, Kubota N, Hatano M, Ueno A, Masugi Y, Sakamoto M. Telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutation correlated with intratumoral heterogeneity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Int. 2020;70:624-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mitas M, Yu A, Dill J, Kamp TJ, Chambers EJ, Haworth IS. Hairpin properties of single-stranded DNA containing a GC-rich triplet repeat: (CTG)15. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1050-1059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Colebatch AJ, Witkowski T, Waring PM, McArthur GA, Wong SQ, Dobrovic A. Optimizing Amplification of the GC-Rich TERT Promoter Region Using 7-Deaza-dGTP for Droplet Digital PCR Quantification of TERT Promoter Mutations. Clin Chem. 2018;64:745-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Corless BC, Chang GA, Cooper S, Syeda MM, Shao Y, Osman I, Karlin-Neumann G, Polsky D. Development of Novel Mutation-Specific Droplet Digital PCR Assays Detecting TERT Promoter Mutations in Tumor and Plasma Samples. J Mol Diagn. 2019;21:274-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cao L, Cui X, Hu J, Li Z, Choi JR, Yang Q, Lin M, Ying Hui L, Xu F. Advances in digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR) and its emerging biomedical applications. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;90:459-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pezzuto F, Izzo F, De Luca P, Biffali E, Buonaguro L, Tatangelo F, Buonaguro FM, Tornesello ML. Clinical Significance of Telomerase Reverse-Transcriptase Promoter Mutations in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:3771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Jang JW, Kim JS, Kim HS, Tak KY, Lee SK, Nam HC, Sung PS, Kim CM, Park JY, Bae SH, Choi JY, Yoon SK. Significance of TERT Genetic Alterations and Telomere Length in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:2160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ko E, Seo HW, Jung ES, Kim BH, Jung G. The TERT promoter SNP rs2853669 decreases E2F1 transcription factor binding and increases mortality and recurrence risks in liver cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:684-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sung WK, Zheng H, Li S, Chen R, Liu X, Li Y, Lee NP, Lee WH, Ariyaratne PN, Tennakoon C, Mulawadi FH, Wong KF, Liu AM, Poon RT, Fan ST, Chan KL, Gong Z, Hu Y, Lin Z, Wang G, Zhang Q, Barber TD, Chou WC, Aggarwal A, Hao K, Zhou W, Zhang C, Hardwick J, Buser C, Xu J, Kan Z, Dai H, Mao M, Reinhard C, Wang J, Luk JM. Genome-wide survey of recurrent HBV integration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:765-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 619] [Cited by in RCA: 745] [Article Influence: 53.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kawai-Kitahata F, Asahina Y, Tanaka S, Kakinuma S, Murakawa M, Nitta S, Watanabe T, Otani S, Taniguchi M, Goto F, Nagata H, Kaneko S, Tasaka-Fujita M, Nishimura-Sakurai Y, Azuma S, Itsui Y, Nakagawa M, Tanabe M, Takano S, Fukasawa M, Sakamoto M, Maekawa S, Enomoto N, Watanabe M. Comprehensive analyses of mutations and hepatitis B virus integration in hepatocellular carcinoma with clinicopathological features. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:473-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yeh SH, Li CL, Lin YY, Ho MC, Wang YC, Tseng ST, Chen PJ. Hepatitis B Virus DNA Integration Drives Carcinogenesis and Provides a New Biomarker for HBV-related HCC. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;15:921-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jang JW, Kim HS, Kim JS, Lee SK, Han JW, Sung PS, Bae SH, Choi JY, Yoon SK, Han DJ, Kim TM, Roberts LR. Distinct Patterns of HBV Integration and TERT Alterations between in Tumor and Non-Tumor Tissue in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:7056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Li CL, Hsu CL, Lin YY, Ho MC, Hu RH, Chen CL, Ho TC, Lin YF, Tsai SF, Tzeng ST, Huang CF, Wang YC, Yeh SH, Chen PJ. HBV DNA Integration into Telomerase or MLL4 Genes and TERT Promoter Point Mutation as Three Independent Signatures in Subgrouping HBV-Related HCC with Distinct Features. Liver Cancer. 2024;13:41-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Nault JC, Martin Y, Caruso S, Hirsch TZ, Bayard Q, Calderaro J, Charpy C, Copie-Bergman C, Ziol M, Bioulac-Sage P, Couchy G, Blanc JF, Nahon P, Amaddeo G, Ganne-Carrie N, Morcrette G, Chiche L, Duvoux C, Faivre S, Laurent A, Imbeaud S, Rebouissou S, Llovet JM, Seror O, Letouzé E, Zucman-Rossi J. Clinical Impact of Genomic Diversity From Early to Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology. 2020;71:164-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Dong R, Najjar G, Günes C, Lechel A. Aberrant TERT expression: linking chronic inflammation to hepatocellular carcinoma(†). J Pathol. 2025;266:130-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sze KM, Ho DW, Chiu YT, Tsui YM, Chan LK, Lee JM, Chok KS, Chan AC, Tang CN, Tang VW, Lo IL, Yau DT, Cheung TT, Ng IO. Hepatitis B Virus-Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase Promoter Integration Harnesses Host ELF4, Resulting in Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase Gene Transcription in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology. 2021;73:23-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Smith-Sonneborn J. Telomerase Biology Associations Offer Keys to Cancer and Aging Therapeutics. Curr Aging Sci. 2020;13:11-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zhu AX, Abbas AR, de Galarreta MR, Guan Y, Lu S, Koeppen H, Zhang W, Hsu CH, He AR, Ryoo BY, Yau T, Kaseb AO, Burgoyne AM, Dayyani F, Spahn J, Verret W, Finn RS, Toh HC, Lujambio A, Wang Y. Molecular correlates of clinical response and resistance to atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Med. 2022;28:1599-1611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 432] [Cited by in RCA: 443] [Article Influence: 110.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/