Published online Dec 28, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i48.113243

Revised: September 28, 2025

Accepted: November 14, 2025

Published online: December 28, 2025

Processing time: 129 Days and 18 Hours

Lifestyle factors are closely associated with the onset and progression of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Studies have demonstrated the positive effects of exercise on clinical outcomes and quality of life in individuals with IBD. Despite the well-documented role of exercise in improving IBD outcomes, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear.

To compare the efficacy of different exercise modalities and explore their potential physiological mechanisms in rodent models of colitis.

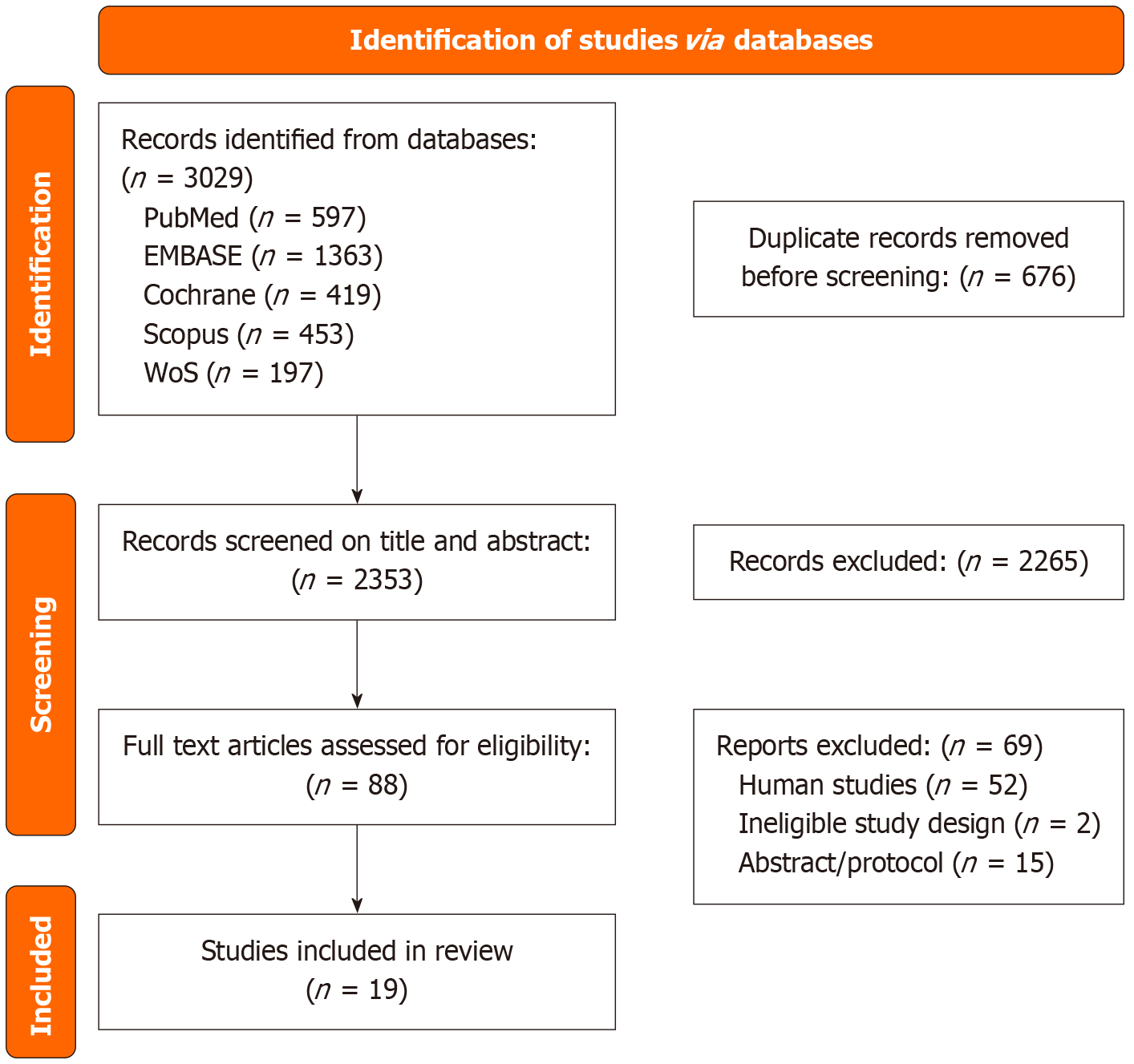

We conducted a comprehensive search of five databases from inception to September 24, 2024, which yielded 19 animal studies in rodent colitis models. We compared the efficacy of various forms of exercise and explored the possible physiological mechanisms. The effects of different exercise modalities, namely forced treadmill running (FTR), voluntary wheel running (VWR), swimming, climbing, and jumping, on both macroscopic symptoms (e.g., body weight, disease activity, and colon length) and microscopic parameters (e.g., histopathology, immune markers, oxidative/antioxidant balance, and gut microbiota) in colitis models were compared.

VWR (simulated recreational physical activity), swimming (aerobic exercise), and strength training (climbing and jumping) consistently promoted overall health in animal colitis models. However, evidence for FTR remains inconsistent, with a notable number of studies suggesting potential exacerbation of colitis symptoms, possibly due to stress or fatigue resulting from its coercive nature. Overall, var

Exercise modality is critical in influencing colitis outcomes, with voluntary and low-stress forms generally being beneficial, while forced exercise may yield adverse effects. These findings highlight the importance of exercise type and individual tolerance in designing therapeutic exercise interventions for IBD. Further research is warranted to establish a robust therapeutic framework for exercise-based interventions in IBD management.

Core Tip: In rodent models of colitis, the impact of exercise on inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is highly modality-dependent. Voluntary wheel running, swimming, and strength training consistently ameliorate colitis by reducing inflammation, oxidative stress, and improving gut barrier integrity. In contrast, forced treadmill running yields inconsistent or detri

- Citation: Sun SP, Mao YQ, Fan YH, Lv B. Exploring exercise modalities and their impact on inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review of rodent colitis models. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(48): 113243

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i48/113243.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i48.113243

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, nonspecific inflammatory condition of the intestine that develops in individuals with genetic susceptibility to environmental risk factors, including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD)[1]. Damage to the intestinal mucosa results in various symptoms, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloody stools with mucus. Periods of disease activity alternating with remission increase the risk of systemic complications and necessitate surgical intervention[2,3].

Epidemiological surveys have indicated that the incidence of IBD in Western countries has stabilized or declined, whereas rates in newly industrialized nations such as China, Japan, and South Korea continue to rise[4,5]. The growing burden of IBD in these regions is believed to be linked to industrialization, drawing increased attention to environmental contributors[6], particularly unhealthy lifestyle patterns such as physical inactivity and consumption of Western diets, which are considered important factors for IBD onset[6].

Currently, IBD is incurable, and medication may be required lifelong to relieve symptoms and control disease pro

Numerous studies have examined the effects of exercise on patients with IBD[10-12]; however, the mechanisms through which exercise exerts its effects remain unclear[8]. In this review, we evaluated the therapeutic potential of PA and investigated its potential mechanisms based on the findings of studies involving rodent IBD models. The findings of this study will provide a reference basis for understanding the preventive potential of exercise in IBD, with implications for future research into its therapeutic applications.

This study was conducted in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses guidelines[13] and was registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews in October 2024 (registration No. CRD42024595793). The review protocol is publicly available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis protocols has been followed, and the checklist was completed.

PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched from their inception date to September 24, 2024. The search was restricted to studies published in English. A combination of disease terms (IBD, UC, and CD) and exercise-related keywords (“physical activity”, “physical exercise”, “sport”, “exercise” and “training”) was used. Reference lists of relevant reviews and included studies were also screened to identify additional eligible studies.

Studies were considered eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) Animal studies with an interventional design; (2) Implementation of a defined exercise protocol for altering subjective and objective parameters in colitis models; (3) Inclusion of either a blank control group or a before–after control group; and (4) Reporting of preclinical findings relevant to the outcomes of interest. Studies were excluded if they: (1) Did not provide sufficient details on the exercise protocol; or (2) Employed an integrated lifestyle intervention in which exercise was only one component.

Two reviewers (Sun SP and Mao YQ) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all retrieved records. Full texts were then assessed whether the studies met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (Zhou M). Data extraction was also conducted independently by Sun SP and Mao YQ by using a standardized data extraction form. The following information was collected: (1) Characteristics of animal models; (2) Type of exercise and control conditions; (3) Exercise parameters, including total number of sessions, intensity, frequency, and duration; (4) Outcome measures; (5) Primary findings related to intervention effects; and (6) Safety and compliance data. Any disagreements during the extraction process were resolved through consultation with the third reviewer (Zhou M).

Two reviewers (Sun SP and Mao YQ) independently evaluated the risk of bias for each included study. The SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool, developed by the Systematic Review Center for Laboratory Animal Experimentation[14], was employed to evaluate methodological quality. The following domains were assessed: Selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other potential sources of bias. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved through consultation with the third reviewer (Zhou M).

Because of a high degree of heterogeneity among the included studies, meta-analyses could not be performed. Instead, the outcomes of exercise interventions were categorized into three domains: Type of exercise, macroscopic parameters [body weight change, disease activity index (DAI), colon length, and macroscopic injury scores], and microscopic parameters (colon histopathology scores, blood and colonic inflammatory parameters, oxidative/antioxidant balance in the colon). Studies reporting the same outcomes were grouped, and comparative results between the exercise and control groups were summarized. In addition, findings comparing the exercise and sedentary conditions in colitis mice with obesity were summarized.

The search process is illustrated in Figure 1. A total of 3029 articles were identified through database searches. After the removal of duplicates, 2353 titles and abstracts were screened, resulting in 88 articles selected for full-text review. Finally, 19 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review. Backward snowballing did not yield any additional eligible studies. The characteristics of the included animal studies are summarized in Table 1[15-33].

| Ref. | Year | Experimental subjects | Modeling method | Exercise type | Exercise parameters |

| Kasimay et al[15] | 2006 | Sprague–Dawley rats | 4% acetic acid, 1 mL, intracolonic administration | FTR | 7 m/minute, 30 minutes/day, 3 days/week, total 6 weeks |

| Saxena et al[16] | 2012 | Adiponectin KO and WT C57BL/6 mice | 2% DSS, drinking water, 5 days | FTR | 18 m/minute, 55 minutes/day, 5 days/week, total 4 weeks |

| Cook et al[17] | 2013 | C57Bl/6 mice | 2% DSS, drinking water, 5 days | FTR | 8-12 m/minute, 40 minutes/day, 5 days/week, total 6 weeks, inclination of 5° |

| Bilski et al[18] | 2015 | Wistar rats | TNBS, 10 mg/kg in 50% ethanol, 250 μL, intracolonic administration | FTR | 20 m/minute, 30 minutes/day, 5 days/week, total 6 weeks |

| Bilski et al[19] | 2019 | C57BL/6 mice | TNBS, 100 μg/g in 40% ethanol, 175 μL, intracolonic administration | FTR | 7.2 m/minute, 30 minutes/day, 7 days/week, total 6 weeks |

| Qonitatillah et al[20] | 2020 | BALB/c mice | λ-carrageenan, 20 mg/L, drinking water, 6 weeks | FTR | 7 m/minute, 30 minutes/day, 3 days/week, total 6 weeks |

| Van Mechelen et al[21] | 2022 | C57BL/6 mice | Acute colitis: 2% DSS, drinking water, 7 days; chronic colitis: Three cycles of 7 days DSS and 14 days recovery | FTR | 11 m/minute, 60 minutes/day, 7 days/week, total 3 weeks, inclination of 5° |

| Hao et al[22] | 2024 | C57BL/6J mice | 2% DSS, drinking water, 7 days | FTR | 10 m/minute, 5 minutes × 10 bouts with 2 minutes of rest, 5 days/week, total 12 weeks |

| Jin et al[23] | 2024 | C57BL/6 mice | 2% DSS, drinking water, 7 days | FTR | 5 m/minute × 10 minutes, 8 m/minute × 50 minutes, total 14 days |

| Wojcik-Grzybek et al[24] | 2024 | C57BL/6 mice | TNBS, 4 mg in 50% ethanol, 175 μL, intracolonic administration | FTR | 6 m/minute, 10 minutes/day, 5 days/week, total 6 weeks |

| Cook et al[17] | 2013 | C57BL/6 mice | 2% DSS, drinking water, 5 days | VWR | 30 days |

| Szalai et al[25] | 2014 | Wistar rats | TNBS, 10 mg in 0.25 mL of 50% ethanol, intracolonic administration | VWR | 6 weeks |

| Liu et al[26] | 2015 | C57BL/6 mice | 2% DSS, drinking water, 5 days | VWR | 30 days |

| Mazur-Bialy et al[27] | 2017 | C57BL/6 mice | TNBS, 100 μg/g in 40% ethanol, 250 μL, intracolonic administration | VWR | 6 weeks |

| Maillard et al[28] | 2019 | CEABAC10 transgenic mice | Bacterial exposure | VWR | 12 weeks |

| Estaki et al[29] | 2020 | Muc2-/- and WT C57BL/6 mice | Muc2-/- idiopathic colitis | VWR | 6 weeks |

| Wojcik-Grzybek et al[30] | 2022 | C57BL/6 mice | TNBS, 4 mg in 50% ethanol, 175 μL, intracolonic administration | VWR | 7 weeks |

| Kolahi et al[31] | 2023 | C57BL/6 mice | 1.5% DSS, drinking water, 7 days | Swimming | 15-20 minutes/day, 5 days/week, for 6 weeks |

| Özbeyli et al[32] | 2016 | Sprague-Dawley rats | 4% acetic acid, 1 mL, intracolonic administration | Swimming | 30 minutes/day, 3 days/week, 5 weeks |

| de Oliveira Santos et al[33] | 2021 | Wistar rats | 4% acetic acid, 1 mL, intracolonic administration | Swimming | 1 hour/day, 5 days/week, 8 weeks |

| Özbeyli et al[32] | 2016 | Sprague-Dawley rats | 4% acetic acid, 1 mL, intracolonic administration | Climb | Rats climbed vertical ladder with a load, 8 repeats 3 sets, 3 days/week, total 5 weeks |

| de Oliveira Santos et al[33] | 2021 | Wistar rats | 4% acetic acid, 1 mL, intracolonic administration | Jump | Rats jump in the water with a load, 4 × 10 repetitions, 60 minutes/day, 5 days/week, total 8 weeks with progressive overload |

The experimental species included C57BL/6 mice (n = 11), Wistar rats (n = 4), Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 3), BALB/c mice (n = 1), heterozygous CEABAC10 transgenic males (n = 1), adiponectin knockout mice (APNKO) (n = 1), and Muc2-/- mice (n = 1).

Colitis was induced using the following methods: Intracolonic administration of acetic acid (n = 5), dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in drinking water (n = 7), intracolonic administration of trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (n = 6), bacterial exposure (n = 1), carrageenan (n = 1), and gene-deficient models (n = 2).

Exercise interventions were categorized as follows: Forced treadmill running (FTR) (n = 10), voluntary wheel running (VWR) (n = 7), swimming (n = 3), climbing (n = 1), and jumping (n = 1). Timing of interventions also varied before colitis induction (n = 12), before and during induction (n = 3), after induction (n = 2), and throughout induction (n = 2).

Regarding outcome measures, 14 studies reported body weight changes, and 10 reported colon length. Fourteen studies assessed macroscopic outcomes such as diarrhea, rectal bleeding, DAI, and gross colonic injury. Seventeen studies reported microscopic parameters, including histopathology (n = 17), immune and inflammatory markers (n = 14), oxidative/antioxidant balance (n = 5), and gut microbiota and metabolite profiles (n = 2).

Four studies were identified as having a high risk of bias in sequence generation and baseline characteristics due to the absence of randomization procedures and lack of baseline information. In four additional studies, it was unclear whether animals were randomly allocated during the experimental process. Only one study explicitly reported random selection of animals for outcome evaluation. Five studies reported blinding of outcome assessors to prevent knowledge of group assignments. One study was judged to have a high risk of bias in the domain of incomplete outcome data due to attrition resulting from animal mortality. All studies exhibited performance bias as none of them provided details regarding allocation concealment or blinding of personnel during the intervention. All studies were considered to have a low risk of reporting bias and other unspecified biases. A visual summary of the quality assessment is presented in Supplementary Figure 1.

All exercise intervention studies reported relevant data on either macroscopic or microscopic outcome indicators in the animal models of colitis. These outcomes were categorized into the following domains: Body weight change, DAI, colon length and macroscopic injury scores, colon histopathology scores, blood and colonic inflammatory parameters, oxidative/antioxidant balance in the colon, and ethological assessments. The effects of different types of exercise on these outcomes in colitis animal models fed on a normal diet are summarized in Table 2.

| Ref. | Exercise type | Macroscopic parameters | Microscopic parameters | Conclusion | |||||||

| Body weight change | Diarrhea and bloody stools | Disease activity index | Colon length or weight | Colon macroscopic injury | Histopathology scores | Blood inflammatory indicators | Colon inflammatory indicators | Colon oxidation/antioxidant balance | |||

| Szalai et al[25] | VWR | No statistical difference | Decreasing | TNF-α mRNA (no change); IL-1β mRNA (decreasing); CXCL1 mRNA (decreasing); IL-10 mRNA (decreasing) | MPO (decreasing); TNF-α mRNA (no change); IL-1β mRNA (decreasing); CXCL1 mRNA (decreasing); IL-10 mRNA (increasing); TNF-α protein (no change) | HO-1 (no change); cNOS (increasing); iNOS (decreasing) | Improving | ||||

| Liu et al[26] | VWR | Increasing | Decreasing | No statistical difference | Decreasing | IL-1β mRNA (no change); IL-1β protein (no change); TNF-α mRNA (decreasing); TNF-α protein (decreasing); IL-6 mRNA (decreasing); IL-6 protein (decreasing) | Improving | ||||

| Mazur-Bialy et al[27] | VWR | No statistical difference | Decreasing | No statistical difference | Increasing | Decreasing | Improving | ||||

| Cook et al[17] | VWR | No statistical difference | Decreasing | No statistical difference | IL-6 mRNA (decreasing); TNF-α mRNA (decreasing); CXCL1 mRNA (decreasing) | Improving | |||||

| Cook et al[17] | FTR | No statistical difference | Increasing | Increasing | IL-1β mRNA (increasing); IL-6 mRNA (increasing); IL-17 mRNA (increasing); IL-10 mRNA (increasing); CCL6 mRNA (increasing) | Exacerbating | |||||

| Kasimay et al[15] | FTR | Decreasing | Decreasing | MPO (decreasing) | MDA (decreasing); GSH (decreasing) | Improving | |||||

| Bilski et al[18] | FTR | Decreasing; CBF (increasing) | IL-1 protein (decreasing); TNF-α protein (decreasing); TWEAK (decreasing); IL-6 protein (increasing); irisin (increasing); leptin (decreasing); adiponectin (no change) | MPO (decreasing) | Improving | ||||||

| Bilski et al[19] | FTR | Increasing | Increasing | Increasing | IL-1 mRNA (increasing); IL-6 mRNA (increasing); TNF-α mRNA (increasing) | MDA (increasing); SOD1 mRNA (increasing); SOD2 mRNA (increasing); GPx mRNA (increasing); COX2 mRNA (increasing); iNOS mRNA (increasing); HIF-α protein (increasing) | Exacerbating | ||||

| Hao et al[22] | FTR | Increasing | Decreasing | Increasing | Decreasing | Improving | |||||

| Jin et al[23] | FTR | Increasing | Decreasing | Increasing | Decreasing | TNF-α (decreasing); IL-1β (decreasing); IL-6 (decreasing) | Improving | ||||

| Van Mechelen et al[21] | FTR | No statistical difference | No statistical difference | CXCL1 (no change); CCL20 (no change); CCL2 (no change) | No impact | ||||||

| Saxena et al[16] | FTR | No statistical difference | No statistical difference | No statistical difference | No statistical difference; BrdU (no change) | Serum APN (increasing) | IL-6 (no change); IL-1β (no change); TNF-α (no change); IL-10 (no change) | No impact | |||

| Qonitatillah et al[20] | FTR | Increasing | Exacerbating | ||||||||

| Kolahi et al[31] | Swimming | No statistical difference | Decreasing | Increasing | Decreasing | Collagen deposition (decreasing) | MDA (decreasing); DTNB (increasing); SOD (increasing); CAT (increasing) | Improving | |||

| de Oliveira Santos et al[33] | Swimming | Increasing | No statistical difference | Decreasing | Decreasing | MPO (decreasing); IL-1β (decreasing); IL-6 (decreasing); TNF-α (decreasing) | NO (decreasing); MDA (decreasing); SOD (increasing) | Improving | |||

| de Oliveira Santos et al[33] | Jumping | No statistical difference | Increasing | Decreasing | Decreasing | MPO (decreasing); IL-1β (decreasing); IL-6 (decreasing); TNF-α (decreasing) | NO (no change); MDA (decreasing); SOD (increasing) | Improving | |||

Resistance to weight loss following colitis induction is widely considered a key objective parameter for evaluating the effectiveness of intervention strategies.

VWR generally had a neutral effect on body weight, with the majority of studies reporting no significant difference compared to sedentary controls[17,25,27]. One study[26], however, noted that VWR conferred significant resistance to weight loss.

In contrast, findings for FTR were inconsistent. Approximately half of the studies reported a beneficial effect on weight maintenance[22,23], while the others found no significant impact[16,17]. This discrepancy may be related to differences in FTR protocols and the associated stress.

Studies on swimming[31] and strength training[33] also showed mixed results, indicating that the effect on body weight may not be a primary or consistent outcome across all exercise types.

In addition to body weight, diarrhea and rectal bleeding are used as subjective indicators for assessing the severity of colitis in animal models. These three parameters form the basis of the DAI, a standardized and widely used scoring system. Because exercise can independently affect body weight, the DAI offers a more comprehensive measure of the therapeutic effect of exercise on disease activity in colitis mice.

Three studies[17,26,27] reported that exercise reduced diarrhea and rectal bleeding in colitis mice. Among these, Mazur-Bialy et al[27] found that VWR did not lead to an increase in DAI scores, indicating no worsening of disease symptoms. Conversely, FTR yielded highly conflicting outcomes. Cook et al[17] observed that FTR worsened diarrhea and bleeding symptoms. Similarly, Bilski et al[19] reported a significant increase in DAI scores following FTR. However, findings from Hao et al[22] and Jin et al[23] indicated that FTR reduced DAI scores in colitis mice. Two additional FTR studies[16,21] found no statistically significant difference. Kolahi et al[31] examined the effects of preintervention aerobic exercise (swimming) and reported a significant reduction in DAI scores among colitis mice.

Sustained inflammation and tissue repair in the colon result in a reduction in total colon length, making it a reliable indicator of disease severity in colitis models. After the entire colon is longitudinally incised postmortem, lesion areas are visually assessed for quantitative scoring by using a macroscopic injury scale[34], a method frequently employed in preclinical studies.

Two studies involving VWR interventions reported changes in colon length. Mazur-Bialy et al[27] found that VWR significantly increased colon length in colitis mouse models, suggesting a protective effect against colonic inflammation. By contrast, Liu et al[26] reported no statistically significant difference in colon length between the VWR and control groups. In addition, Szalai et al[25] observed that VWR significantly reduced macroscopic injury scores in the colon, further supporting its potential therapeutic effect in colitis models.

Three studies examining FTR reported changes in colon length in colitis mouse models. Hao et al[22] and Jin et al[23] found that FTR increased colon length. By contrast, Saxena et al[16] reported no significant difference in colon length between the FTR and control groups. In addition, three FTR studies evaluated macroscopic injury scores. Both Kasimay et al[15] and Bilski et al[18] observed reductions in injury scores. However, Bilski et al[19] reported an increase in macroscopic injury scores after FTR.

Kolahi et al[31] investigated the effect of swimming on colon length in colitis models and found that swimming exercise significantly increased the total colon length compared with sedentary controls, indicating a protective effect against inflammation-induced shortening. Similarly, de Oliveira Santos et al[33] reported that both swimming and jump training reduced the macroscopic colon injury scores relative to the non-exercise group.

Microscopic mucosal damage is typically assessed using hematoxylin and eosin staining to evaluate intestinal epithelial injury, the degree of inflammatory cell infiltration, and the extent of crypt loss. Myeloperoxidase (MPO), an enzyme predominantly found in the azurophilic granules of neutrophils and monocytes, is released in large amounts during mucosal injury. Therefore, MPO activity serves as an additional marker for assessing the severity of intestinal inflammation and mucosal damage[35].

Liu et al[26] and Mazur-Bialy et al[27] reported that VWR significantly reduced mucosal pathology scores in colitis mice compared with sedentary controls. However, Cook et al[17] found no significant difference in histopathological scores between the VWR and sedentary groups. Through immunohistochemical analysis, Szalai et al[25] found a significant reduction in MPO expression levels in the colon of the VWR group.

Eight studies involving FTR reported the pathological outcomes. Among them, three studies[15,22,23] demonstrated that FTR reduced mucosal damage and pathological scores. By contrast, three studies[17,19,20] found that FTR aggravated mucosal injury. The remaining two studies[16,21] reported no statistically significant differences in the histopathological scores between the FTR and control groups. Kasimay et al[15] also noted a reduction in MPO expression in colitis mice after FTR compared with sedentary controls.

Two studies[31,33] examining swimming and jump training interventions reported significant reductions in the histopathological scores and MPO expression, suggesting that these exercise modalities mitigate mucosal damage in colitis models.

An imbalance in intestinal mucosal immunity disrupts the structural integrity of the mucosa. Therefore, regulating the levels of systemic and local proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines is a key objective for evaluating the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions.

Three studies examined the effects of VWR on inflammatory parameters. Szalai et al[25] compared sedentary and VWR-exercised colitis mice and found that VWR significantly reduced CXCL1 and interleukin (IL)-1β expressions in both blood and colon. IL-10 messenger RNA (mRNA) levels were increased in the colon but decreased in blood. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α levels remained unchanged in both compartments. Liu et al[26] found that VWR downregulated TNF-α and IL-6 at both the gene and protein levels in the colon but had no effect on IL-1β. Cook et al[17] reported that VWR significantly reduced CXCL1, IL-6, and TNF-α mRNA levels in the colonic tissue.

Six studies evaluated the effect of FTR on inflammatory markers. Bilski et al[18] observed that FTR downregulated IL-1β, TNF-α, and TNF-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) expression but upregulated IL-6. Jin et al[23] also reported reductions in TNF-α and IL-1 along with a decrease in IL-6. By contrast, two other studies found that FTR worsened inflammation: Cook et al[17] reported the upregulation of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17, IL-10, and CCL6 in blood, and Bilski et al[19] found elevated levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in the colon. Saxena et al[16] found no significant effect of FTR on IL-6, IL-1, TNF-α, or IL-10 in the intestinal mucosa. Van Mechelen et al[21] reported no significant changes in CXCL1, CCL20, or CCL2 expression in the colon following FTR. de Oliveira Santos et al[33] investigated the effects of swimming and jump training on colitis-related inflammation and found that both interventions significantly reduced IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in the intestinal mucosa.

High levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) during intestinal inflammation contribute to oxidative stress, which disrupts physiological homeostasis and results in cellular damage. Such damage includes lipid peroxidation, protein modification, and excessive production of proinflammatory cytokines, all of which are closely associated with the onset and progression of IBD. Malondialdehyde (MDA) is the most widely used biomarker of lipid peroxidation. Maintaining redox balance in the colon depends on the coordinated activity of several enzymes. Antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) play direct roles in ROS elimination. Other enzymes regulate oxidative stress indirectly; for example, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) degrades heme into biliverdin, carbon monoxide, and ferrous iron, thereby exerting antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Nitric oxide (NO) synthase (NOS) exists in three isoforms neuronal (nNOS), endothelial (eNOS), and inducible (iNOS) each of which catalyzes NO production and contributes to redox regulation. Notably, iNOS produces large quantities of NO during inflammation, potentially aggravating oxidative stress. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NOX) enzymes, such as NOX2 and NOX4, are also significant sources of ROS. Additionally, the overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 at inflammatory sites can elevate prostaglandin E2 levels, further promoting oxidative stress and inflammation.

In a study by Szalai et al[25], oxidative stress markers, including HO-1, constitutive isoforms of eNOS or nNOS (cNOS), and iNOS, were measured in colitis mice exposed to sedentary conditions vs VWR. The results revealed that VWR significantly reduced the expression of iNOS and upregulated the expression of cNOS but had no significant effect on HO-1 levels.

Kasimay et al[15] demonstrated that compared with sedentary colitis mice, those trained with FTR exhibited decreased levels of colonic MDA, a marker of lipid peroxidation. However, this reduction was accompanied by a decrease in glutathione (GSH) content. By contrast, Bilski et al[19] reported opposing results: FTR-trained mice showed significantly increased levels of colonic MDA and mRNA markers, including iNOS and cyclooxygenase-2. This study also found significant upregulation of antioxidant enzymes at the mRNA level, including SOD1, SOD2, and GPx.

Two studies[31,33] compared oxidative stress parameters between the swimming-trained and sedentary colitis mouse models. Both studies found that swimming significantly reduced the MDA level and increased the expression of antioxidant markers, such as SOD and CAT. In addition, de Oliveira Santos et al[33] reported that high jump training enhanced the antioxidant capacity by modulating the expression of MDA and increasing the expression of SOD.

Kasimay et al[15] investigated the potential antianxiety effects of FTR in colitis mice by using the Holeboard test, which was conducted 24 hours before and 48 hours after colitis induction. Prior to disease induction, the FTR group exhibited significantly shorter freezing times on the perforated platform than the sedentary group, suggesting that exercise training had an anxiolytic effect. After colitis induction, the exercise-trained rats did not exhibit anxiety-like behavior, in contrast to the sedentary colitis group, indicating that FTR may alleviate anxiety symptoms associated with colitis.

In summary, while VWR, swimming, and strength training consistently demonstrated protective effects against colitis, FTR yielded conflicting outcomes. A notable proportion of FTR studies reported exacerbation of disease activity, histological damage, or inflammatory markers, particularly under high-intensity or forced conditions, suggesting that the coercive nature of FTR may counteract its potential benefits.

Given the potential weight-reducing and anti-inflammatory effects of exercise, researchers have investigated its impact in obese animal models of colitis and examined the underlying mechanisms. Table 3 summarizes the outcome data from studies evaluating exercise interventions in these models.

| Ref. | Diet | Model | Exercise | Outcomes |

| Mazur-Bialy et al[27] | HFD: 42% fat, 5495.855 kcal/kg; SD: 3518.05 kcal/kg | TNBS | VWR | Macroscopic parameters: Body weight (decreasing), mesenteric fat pad/body weight (decreasing), colonic blood flow (increasing), DAI (decreasing); Plasma level: TNF-α (decreasing), MCP-1 (decreasing), IL-6 (decreasing), IL-13 (decreasing), IL-17 (decreasing), IL-1α (decreasing), KC (decreasing), IL-4 (decreasing), leptin (decreasing), irisin (increasing), adiponectin (increasing); White adipose tissue: TNF-α (decreasing), IL-6 (decreasing), MCP-1 (decreasing), leptin (decreasing), adiponectin (increasing) |

| Wojcik-Grzybek et al[30] | HFD: 42% fat, 5495.855 kcal/kg; SD: 3518.05 kcal/kg | TNBS | VWR | Macroscopic parameters: Body weight (decreasing), grip strength test (increasing), DAI (decreasing); Colon parameters: MDA/4-HNE (decreasing), 8-OHdG (decreasing), GSH/GSSG (increasing), SOD (decreasing); Plasma level: IL-2 (increasing), IL-10 (decreasing), IL-17α (decreasing), MCP-1 (decreasing), IL-6 (decreasing), IL-12 p70 (decreasing), TNF-α (decreasing), leptin (decreasing) |

| Maillard et al[28] | High-fat and sugar diet: 13.2% proteins, 58.7% lipids, 28.1% carbohydrates(sucrose), 5317 kcal/kg | CEABAC10 transgenic mice + invasive Escherichia coli | VWR | Macroscopic parameters: Body weight (no change), mesenteric adipose tissue (decreasing); Plasma level: Active LPS (no change); Colon tight junction proteins: Occludin (increasing), ZO-1 (increasing); Fecal SCFAs: Propionate (increasing), butyrate (increasing), acetate (no change); Gut microbiota: Α-diversity (no change), β-diversity (increasing), Ruminococcus (increasing), Oscillospira (increasing) |

| Bilski et al[18] | HFD: 70% cholesterol; LFD: 10% cholesterol; SD: < 5% of total fat | Wistar rats with TNBS | FTR | Macroscopic parameters: Area of colonic lesions(decreasing), colonic blood flow (increasing), weight of colonic tissue (decreasing); Plasma level: IL-1β (decreasing), TNF-α (decreasing), TWEAK (decreasing), irisin (increasing), IL-6 (increasing); Colon parameters: MPO activity (decreasing), leptin (decreasing), adiponectin (increasing), IL-1β (decreasing), TNF-α (decreasing), HIF-1α (decreasing) |

| Bilski et al[19] | HFD: 42% fat | C57BL/6 TNBS | FTR | Macroscopic parameters: DAI (increasing), CBF (decreasing), histological score (increasing), energy intake (decreasing); Colon inflammatory parameters: TNF-mRNA (increasing), TNF-protein (increasing), IL-1 mRNA (increasing), IL-1 protein (increasing), IL-6 mRNA (increasing), IL-6 protein (increasing), IL-17 (increasing), IL-10 (increasing), IFN-γ (increasing); Colon oxidation and antioxidant parameters: MDA/4-HNE (increasing), GSH (increasing), SOD (increasing), HO-1 mRNA (no change), iNOS mRNA (increasing), COX2 mRNA (increasing), HO-1 protein (no change), HIF-1α protein (increasing) |

Two studies[27,30] examining VWR in colitis models, fed on a high-fat diet (HFD), showed that VWR significantly reversed HFD-induced weight gain and disease activity, notably by reducing the mesenteric fat pad as a proportion of total body weight. In the study by Mazur-Bialy et al[27], the levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were measured in both blood and white adipose tissue of sedentary and VWR-trained obese colitis mice. Compared with sedentary controls, VWR significantly reduced the circulating levels of chemokines [monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and murine chemokine], proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-13, IL-17, and IL-1α), and regulatory cytokines (IL-3 and IL-4). In white adipose tissue, TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1 levels were also reduced. In addition, VWR increased the levels of adiponectin and irisin but reduced the level of leptin. The study by Wojcik-Grzybek et al[30] reported similar anti-inflammatory effects and also evaluated markers of oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. VWR intervention resulted in decreased oxidative stress, as evidenced by decreased MDA/4-hydroxynonenal and 8-oxo-2’-deoxyguanosine levels, increased GSH, and a paradoxical decrease in SOD. Another VWR study[28] used genetically susceptible CD mouse models, which were exposed to invasive Escherichia coli and fed a high-fat, high-sugar diet. The results revealed that although body weight remained unchanged, VWR significantly reduced mesenteric adipose tissue mass and upregulated the expression of the colonic tight junction proteins, occludin and zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1). Moreover, VWR increased the diversity of gut microbiota, abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria, and fecal levels of propionate and butyrate.

Two animal studies by Bilski et al[18] and Bilski et al[19] evaluated the effects of FTR in colitis models under HFD conditions and reported conflicting results. In Wistar rats with colitis induced under HFD, preintervention with FTR reduced disease activity and colon tissue weight but increased colonic blood flow. Moreover, FTR increased the circulating levels of muscle-derived factors such as irisin and IL-6 and significantly reduced the concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines, IL-1β, TNF-α, and TWEAK, in both blood and intestinal tissue. By contrast, in a separate study using C57BL/6 mice with HFD-induced colitis, FTR worsened disease outcomes. Specifically, FTR increased both the DAI and histopathological scores compared with the sedentary group. Additionally, FTR markedly upregulated the mRNA and protein levels of several proinflammatory cytokines in the colon, increased oxidative stress, and reduced antioxidant capacity.

The mechanisms through which exercise affects intestinal health remain an emerging area of research. Several animal studies on the mechanism underlying the therapeutic effects of exercise are ongoing.

Most studies have implemented exercise interventions prior to disease induction, thereby providing evidence for the preventive effects of exercise. The therapeutic potential of exercise administered after disease onset remains less explored. To address this limitation, Estaki et al[29] used Muc2-/- mice, an established lifelong model of murine colitis, to evaluate the preventive efficacy of VWR. Muc2-/- mice develop early signs of colitis at birth, and these symptoms aggravate by 3 months of age. The study found that VWR did not improve the histopathological or clinical symptom scores in Muc2-/- mice compared with sedentary controls. Furthermore, although VWR demonstrated significant benefits in wild-type (WT) mice, it did not affect colonic inflammatory cytokines, short-chain fatty acid levels, or gut microbiota diversity in the Muc2-/- mice. These findings suggest that the protective effects of exercise depend on the presence of an intact intestinal mucus barrier because the absence of this layer suppressed the observed benefits.

Hao et al[22] demonstrated that following FTR intervention, β-hydroxybutyrate (β-HB) levels in blood increased significantly, suggesting that β-HB plays a role in delaying DSS-induced colitis. When β-HB production was inhibited, the protective effect of FTR preconditioning against colitis weakened. By contrast, supplementation with β-HB effectively restored the protective effect. Mechanistic investigations revealed that β-HB enhances histone H3 acetylation at the promoter region, upregulates the expression of forkhead box protein P3, and directly promotes the differentiation of regulatory T (Treg) cells, thereby reducing the colonic helper T (Th) 17/Treg cell ratio. Furthermore, β-HB treatment increased fatty acid oxidation, a key metabolic pathway essential for Treg cell differentiation. Notably, β-HB administration in the absence of exercise also significantly increased colonic Treg cell levels and ameliorated colitis symptoms. These findings indicate that exercise-derived metabolites such as β-HB exert protective effects against colitis and may serve as potential alternatives to exercise interventions; however, the extent to which such metabolites can substitute for exercise remains to be fully elucidated.

Jin et al[23] compared the therapeutic efficacy of FTR and 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) against UC in mice, assessing both monotherapy and combination therapy. FTR was administered during the recovery phase of colitis to evaluate its curative potential. The results indicated that combined FTR and 5-ASA treatment produced more pronounced therapeutic effects than either intervention alone. These effects included improved histological architecture; increased body weight, colon weight, and colon length; and decreased DAI scores and collagen deposition. In addition, the combination therapy inhibited the activation of the nuclear factor kappa-B/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway, suppressed proinflammatory cytokine expression, and reduced cell apoptosis following colitis. This study highlights the potential of exercise as an effective adjuvant to pharmacological treatment in UC.

Adiponectin is an anti-inflammatory agent, and previous research has demonstrated that exercise can reverse its colitis-induced downregulation. Saxena et al[16] investigated the efficacy of FTR using APNKO and WT C57BL/6 mice. The study found that APNKO mice treated with DSS exhibited more severe macroscopic parameters than DSS-treated WT mice. In APNKO mice, increased susceptibility to colitis was associated with enhanced signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) phosphorylation and elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-10. Furthermore, a comparison between FTR and sedentary APNKO colitis mice revealed that exercise significantly mitigated the detrimental effects of adiponectin deficiency, potentially by reducing STAT3 phosphorylation.

Smoking is an independent risk factor for IBD. Özbeyli et al[32] examined the effects of swimming (aerobic exercise) and jump training (resistance exercise) on colitis in rats exposed to second-hand smoke (SHS). The results demonstrated that compared with the sedentary SHS-colitis group, the swimming group exhibited significantly reduced scores for both macroscopic and microscopic injuries as well as MDA and ROS levels. Jump training significantly reduced microscopic scores, MPO activity, and MDA and ROS levels. These findings suggest that both aerobic and resistance exercise confer protective effects against SHS-exacerbated UC.

Currently, there is no definitive cure for IBD, making lifestyle interventions, such as PA, increasingly important for prevention and symptom management[36]. This review summarizes the results of studies investigating the preventive effects and underlying mechanisms of exercise in animal models of colitis. Our findings indicated that different types of exercise had varying effects on both macroscopic and microscopic parameters in colitis models. Overall, VWR, swim

The included studies exhibited considerable heterogeneity in experimental parameters, which may account for the divergent outcomes observed, particularly regarding the efficacy of FTR. The most striking difference was observed between FTR and VWR exercise. VWR consistently demonstrated beneficial effects across studies[17,25-27], whereas FTR yielded mixed results (improvement[15,18,22,23], exacerbation[17,19,20], or no effect[16,21]). This suggests that the stress associated with forced exercise may counteract its anti-inflammatory benefits in susceptible models. Within FTR studies, parameters varied widely (e.g., speed: 5-18 m/minute; duration: 10-60 minute/session; total period: 2-12 weeks). A trend suggested that milder protocols (e.g., 7 m/minute, 30 minutes[15]) were associated with improvement, while more intense regimens (e.g., 18 m/minute, 55 minutes[16]; or during disease[17]) were linked to null or negative effects. However, the limited number of studies precludes a definitive conclusion on intensity thresholds.

Most studies have primarily investigated the preventive effects of exercise interventions prior to colitis induction. Only two studies have examined exercise interventions during the recovery phase of colitis, possibly due to the physical limitations imposed by colitis symptoms, which can hinder animal mobility and complicate the assessment of exercise outcomes. Ethical considerations may also restrict the implementation of exercise protocols, such as FTR during active disease phases. While most animal studies implemented exercise prior to colitis highlighting its preventive potential the feasibility and safety of exercise during the active disease phase remain clinically pertinent. Our review included only two studies that applied FTR during active colitis, both of which reported worsened disease outcomes. This suggests that high-intensity or forced exercise may be detrimental amid active inflammation. Future research should prioritize evaluating patient-tailored, low-stress exercise regimens during active disease, incorporating objective monitoring of inflammatory markers and patient-reported outcomes to establish evidence-based guidelines for PA in acute IBD.

The response to exercise may be model-dependent. The included studies utilized two predominant chemically-induced colitis models: DSS and trinitro-benzene-sulfonic acid (TNBS). These models represent distinct pathophysiological features of IBD. The DSS model primarily induces epithelial barrier damage and acute mucosal inflammation, mimicking human UC, characterized by neutrophil infiltration, weight loss, diarrhea, and colon shortening. In contrast, the TNBS model elicits a Th1-driven transmural inflammation with granulomatous features, more representative of CD. Our review noted variability in exercise outcomes depending on the model used. For instance, FTR yielded conflicting results in DSS-induced colitis while in TNBS models, FTR was more frequently associated with aggravated inflammation. This discrepancy may be attributable to the heightened immune activation and stress sensitivity in the TNBS model, wherein the stress of forced exercise could potentiate inflammatory pathways. Therefore, the choice of colitis model is a critical factor in interpreting exercise interventions, and future preclinical studies should explicitly consider model-specific pathophysiology when designing and translating exercise protocols. In addition, most studies have induced colitis by using 2% DSS, rather than the commonly used 3% concentration, which may help avoid severe symptoms that could obscure the protective effects of exercise. Across various subjective and objective outcome measures, interventions involving VWR as a form of recreational PA, swimming as simulated aerobic exercise, and high jump as strength training have been reported to exert beneficial effects on the overall health of colitis animals. By contrast, findings on FTR remain contradictory; while some studies report improvements in colitis symptoms, others indicate no significant anti-inflammatory effect or even exacerbation of disease. These inconsistencies may stem from the coercive nature of FTR, potentially leading to exercise-induced fatigue or additional physiological stress. Also, genetic background (e.g., C57BL/6 vs Wistar rats) may further modulate this response. However, current evidence does not allow for valid conclusions, and future studies are needed to compare this difference across different genetic backgrounds.

Quantifiable changes in body weight were considered a key indicator because resistance to weight loss was used to assess intervention efficacy. This review found that in animal models of colitis with a normal diet, exercise showed resistance to disease-induced weight loss, while in obese models, it significantly reduced weight. This seemingly contradictory result actually reflects the bidirectional regulatory ability of exercise on energy metabolism and body composition. In non-obese models, colitis often leads to pathological weight loss, and exercise helps maintain weight stability through anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and improved intestinal barrier function. In obese models, exercise effectively controls weight gain by reducing fat mass, improving insulin sensitivity and regulating adipokines secretion (such as increasing adiponectin and reducing leptin), without compromising lean body mass. Therefore, the role of exercise in the management of colitis depends not only on the disease state, but also on the individual’s metabolic background, reflecting its potential for “metabolic normalization”. Moving forward, the development of a more objective and standardized scoring system for colitis mice undergoing exercise interventions is essential.

Histopathological scoring of colon tissue through hematoxylin-eosin staining is an accurate microscopic indicator for evaluating the effects of exercise interventions based on observations of the mucosa, glands, and inflammatory cell infiltration. In addition, MPO staining can be used as a semi-quantitative marker for assessing the extent of inflammatory infiltration. Multiple studies have shown that VWR, aerobic training (e.g., swimming), and strength training can mitigate histopathological damage in colitis models. However, the effects of FTR remain controversial; while some studies suggest that FTR exacerbates colitis, others report beneficial outcomes. These inconsistencies may be attributed to specific FTR parameters, including stress induced by coercion or fatigue from excessive exercise intensity. Clinical studies have indicated that patients’ subjective experience of exercise, whether positive or negative, can affect the therapeutic benefits of training programs[37,38]. Accordingly, future studies should consider modifying FTR protocols to reduce stress and identify optimal exercise intensities. As a voluntary form of PA, VWR prevents stress and exercise-induced fatigue. However, most VWR studies have used single-cage housing, likely to ensure adequate exercise levels, instead of group-cage settings. By contrast, Loudon et al’s clinical study demonstrated that a 3-month group walking program improved quality of life in patients with CD[39]. Ng et al[40] further evaluated an individual walking program, aiming to isolate the effects of PA from those of social interaction. These findings suggest that the benefits of group-based exercise may be partially attributed to interpersonal engagement. Therefore, future studies should comparatively analyze the effects of individual and group-based exercise in animal models of colitis.

The dynamic balance of intestinal mucosal immunity and the structural integrity of the intestinal mucosa are maintained through the complex interactions among mucosal epithelial cells, stromal cells, mast cells, endothelial cells, and immune cells[41]. Disruption of these interactions can result in tissue damage and chronic inflammation, ultimately contributing to the development and progression of IBD. Moderate exercise exerts beneficial effects on intestinal immunity. In particular, regular PA reduces systemic inflammatory markers, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and C-reactive protein, especially in individuals with obesity or metabolic syndrome. Additionally, exercise enhances mucosal immunity by promoting the secretion of intestinal immunoglobulin A and modulating the Th1/Th2 immune balance, thereby lowering the risk of allergic and autoimmune conditions. Evidence from the animal studies included in the present review further supports the anti-inflammatory effects of exercise, demonstrating its capacity to reverse the elevated inflammatory status in both peripheral blood and colonic tissue in colitis models, primarily through the significant reduction of proinflammatory cytokine levels.

Oxidative stress and disruption of the antioxidant defense system are key mechanisms underlying the onset and progression of IBD. Inflammatory activity, immune cell activation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and abnormal metabolism of intestinal epithelial cells contribute to the excessive production of ROS, resulting in pathological outcomes such as mucosal barrier disruption, lipid peroxidation, and DNA damage. Exercise exerts a bidirectional regulatory effect on oxidative stress. While moderate exercise can enhance the body’s antioxidant defense system, excessive PA may exacerbate oxidative stress. This review summarizes evidence supporting the beneficial impact of exercise on oxidative/antioxidant balance in colitis mouse models. Specifically, exercise interventions have been shown to reduce oxidative markers, such as MDA and NO, and significantly increase antioxidant levels, including GSH and SOD.

The correlation between exercise and gut microbiota may help explain the overall health benefits of PA[42]. However, no microbiological evidence currently exists regarding the benefits of exercise intervention in colitis mice maintained on a standard diet. Maillard et al[28] investigated changes in gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids in colitis mice fed a high-fat, high-sugar diet following VWR. The study reported that VWR significantly increased the intestinal levels of propionate and butyrate. While alpha diversity of gut microbiota remained unchanged, beta diversity was significantly increased. In line with the elevated butyrate levels, the abundance of butyrate-producing genera such as Ruminococcus and Oscillospira was higher in the VWR group than in controls. Furthermore, VWR significantly upregulated the expression of ZO-1 and occludin key markers of intestinal epithelial tight junction, indicating that VWR is beneficial for maintaining intestinal mucosal stability.

Clinical studies suggest that exercise interventions do not effectively reduce the disease activity or recurrence rate of IBD, but they significantly improve patient-reported outcomes, particularly those related to mental health[43,44]. Previous studies have reported that exercise may modulate gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acid levels, thereby affecting the gut-brain axis. However, our review indicates limited exploration of these mechanisms in animal models. Only one study by Kasimay et al[15] investigated the anxiolytic effects of FTR in colitis mice, and only one study[28] examined gut microbiota and changes in short-chain fatty acid following exercise training. This study demonstrated that exercise can enhance microbial diversity, especially by increasing the abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria and the concentrations of butyrate salts. These findings indicate the metabolic and microbiota-mediated benefits of exercise and support its role in promoting a healthy lifestyle among individuals with IBD.

Current research still provides limited insight into the mechanisms underlying the effects of exercise interventions in colitis animal models. Estaki et al[29] suggested that the presence of an intact mucosal layer may be essential for the efficacy of exercise, implying that exercise should be avoided during the acute phase or in case of mucosal injury. Additionally, several studies have detected exercise-induced myokines such as irisin and IL-6, but their specific pathways of action on the intestine remain unclear. Previous studies have shown that irisin can enhance the intestinal barrier[45] and modulate the gut-brain axis to improve cognitive functions[46]. Furthermore, Hao et al[22] demonstrated the gut-protective effects of exercise-derived metabolites. Future research should identify and characterize exercise-related changes in the microbiota and metabolites, which may help develop therapeutic alternatives for patients with IBD who are unable to engage in PA.

The collective evidence from this systematic review suggests that the beneficial effects of exercise in rodent colitis models are not attributable to a single mechanism but rather emerge from a coordinated network of physiological adaptations. This network can be conceptualized as a cycle of mutual reinforcement, centered on the core axis of gut barrier integrity, immune homeostasis, and microbial harmony, supported by exercise-induced enhancements in antioxidant capacity and metabolic regulation. VWR, swimming, and resistance training appear to positively engage this network by reducing physiological stress. In contrast, FTR may disrupt it, leading to inconsistent outcomes. Specifically, exercise-induced changes in gut microbiota composition and increased production of microbial metabolites like short-chain fatty acids and β-HB are pivotal. These metabolites not only strengthen the intestinal barrier by upregulating tight junction proteins but also directly modulate immune responses, for instance, by promoting the differentiation of Treg cells and suppressing pro-inflammatory pathways. Simultaneously, the augmentation of antioxidant defenses mitigates oxidative tissue damage, thereby breaking the cycle of inflammation and epithelial injury. Thus, the protection conferred by appropriate exercise modalities stems from their ability to simultaneously target multiple, interconnected nodes of colitis pathophysiology, restoring overall intestinal homeostasis.

This review highlights exercise’s benefits on oxidative stress, inflammation, and gut microbiota in colitis models. These findings intersect with emerging IBD therapeutic frontiers. The ability of exercise to mitigate oxidative stress aligns with novel strategies targeting ROS pathways. Furthermore, exercise-induced microbiota modulation, such as enriching butyrate producers, complements the goals of targeted microbial therapies like precision probiotics or FMT. Future research should explore potential synergies between exercise and these advanced modalities, paving the way for multi-faceted IBD management strategies that integrate lifestyle and technological innovations.

This study has several limitations. The included studies exhibit considerable heterogeneity in experimental design, exercise modalities, exercise parameters, animal models, and other aspects. A meta-analysis was not performed, and the findings were presented only through qualitative descriptions, thereby reducing the statistical strength of the con

Understanding the preventive effects of exercise on colitis may offer valuable insights for managing lifestyle in individuals with IBD. Further research is needed to clarify its therapeutic potential in active disease. This review examined the potential impact of various types of exercise on both macroscopic and microscopic outcomes in animal models of colitis and examined the underlying physiological mechanisms. Therefore, this study holds relevance in elucidating the relationship between PA and IBD. However, the complex interrelationships among exercise, broader lifestyle factors, and IBD outcomes remain to be fully characterized. This review may serve as a reference for future research into the mechanisms through which exercise affects the course of IBD.

We thank the animals that have sacrificed for scientific research.

| 1. | Kaplan GG, Windsor JW. The four epidemiological stages in the global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:56-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 927] [Article Influence: 185.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Adamina M, Minozzi S, Warusavitarne J, Buskens CJ, Chaparro M, Verstockt B, Kopylov U, Yanai H, Vavricka SR, Sigall-Boneh R, Sica GS, Reenaers C, Peros G, Papamichael K, Noor N, Moran GW, Maaser C, Luglio G, Kotze PG, Kobayashi T, Karmiris K, Kapizioni C, Iqbal N, Iacucci M, Holubar S, Hanzel J, Sabino JG, Gisbert JP, Fiorino G, Fidalgo C, Ellu P, El-Hussuna A, de Groof J, Czuber-Dochan W, Casanova MJ, Burisch J, Brown SR, Bislenghi G, Bettenworth D, Battat R, Atreya R, Allocca M, Agrawal M, Raine T, Gordon H, Myrelid P. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn's Disease: Surgical Treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18:1556-1582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ben Hur D, Issaschar G, Moshe R, Lebedenko B, Lujan R, Haklai Z, Loewenberg Weisband Y, Ben-Tov A, Lederman N, Matz E, Dotan I, Turner D, Pinto GD, Waterman M. Risk of Age-related and Disease-related Complications and Mortality in Elderly-onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Population-based Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;23:1982-1990.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Buie MJ, Quan J, Windsor JW, Coward S, Hansen TM, King JA, Kotze PG, Gearry RB, Ng SC, Mak JWY, Abreu MT, Rubin DT, Bernstein CN, Banerjee R, Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Panaccione R, Seow CH, Ma C, Underwood FE, Ahuja V, Panaccione N, Shaheen AA, Holroyd-Leduc J, Kaplan GG; Global IBD Visualization of Epidemiology Studies in the 21st Century (GIVES-21) Research Group, Balderramo D, Chong VH, Juliao-Baños F, Dutta U, Simadibrata M, Kaibullayeva J, Sun Y, Hilmi I, Raja Ali RA, Paudel MS, Altuwaijri M, Hartono JL, Wei SC, Limsrivilai J, El Ouali S, Vergara BI, Dao VH, Kelly P, Hodges P, Miao Y, Li M. Global Hospitalization Trends for Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis in the 21st Century: A Systematic Review With Temporal Analyses. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:2211-2221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 40.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Park J, Cheon JH. Incidence and Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease across Asia. Yonsei Med J. 2021;62:99-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Piovani D, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Nikolopoulos GK, Lytras T, Bonovas S. Environmental Risk Factors for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: An Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:647-659.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 570] [Article Influence: 81.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Papamichael K, Afif W, Drobne D, Dubinsky MC, Ferrante M, Irving PM, Kamperidis N, Kobayashi T, Kotze PG, Lambert J, Noor NM, Roblin X, Roda G, Vande Casteele N, Yarur AJ, Arebi N, Danese S, Paul S, Sandborn WJ, Vermeire S, Cheifetz AS, Peyrin-Biroulet L; International Consortium for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. Therapeutic drug monitoring of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: unmet needs and future perspectives. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:171-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen J, Sun S. Unlocking the Power of Physical Activity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2024;2024:7138811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sun SP, Chen JJ, Zheng MX, Fan YH, Lv B. Progress in research of exercise intervention in inflammatory bowel disease. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2024;32:339-346. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Protano C, Gallè F, Volpini V, De Giorgi A, Mazzeo E, Ubaldi F, Romano Spica V, Vitali M, Valeriani F. Physical activity in the prevention and management of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. J Public Health (Berl). 2024;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Trivić I, Sila S, Mišak Z, Niseteo T, Batoš AT, Hojsak I, Kolaček S. Impact of an exercise program in children with inflammatory bowel disease in remission. Pediatr Res. 2023;93:1999-2004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Seeger WA, Thieringer J, Esters P, Allmendinger B, Stein J, Schulze H, Dignass A. Moderate endurance and muscle training is beneficial and safe in patients with quiescent or mildly active Crohn's disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:804-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 52110] [Article Influence: 10422.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RB, Leenaars M, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, Langendam MW. SYRCLE's risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2511] [Cited by in RCA: 2892] [Article Influence: 241.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Kasimay O, Güzel E, Gemici A, Abdyli A, Sulovari A, Ercan F, Yeğen BC. Colitis-induced oxidative damage of the colon and skeletal muscle is ameliorated by regular exercise in rats: the anxiolytic role of exercise. Exp Physiol. 2006;91:897-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Saxena A, Fletcher E, Larsen B, Baliga MS, Durstine JL, Fayad R. Effect of exercise on chemically-induced colitis in adiponectin deficient mice. J Inflamm (Lond). 2012;9:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cook MD, Martin SA, Williams C, Whitlock K, Wallig MA, Pence BD, Woods JA. Forced treadmill exercise training exacerbates inflammation and causes mortality while voluntary wheel training is protective in a mouse model of colitis. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;33:46-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bilski J, Mazur-Bialy AI, Brzozowski B, Magierowski M, Jasnos K, Krzysiek-Maczka G, Urbanczyk K, Ptak-Belowska A, Zwolinska-Wcislo M, Mach T, Brzozowski T. Moderate exercise training attenuates the severity of experimental rodent colitis: the importance of crosstalk between adipose tissue and skeletal muscles. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:605071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bilski J, Mazur-Bialy A, Wojcik D, Magierowski M, Surmiak M, Kwiecien S, Magierowska K, Hubalewska-Mazgaj M, Sliwowski Z, Brzozowski T. Effect of Forced Physical Activity on the Severity of Experimental Colitis in Normal Weight and Obese Mice. Involvement of Oxidative Stress and Proinflammatory Biomarkers. Nutrients. 2019;11:1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Qonitatillah A, Wigati KW, Irawan R. Physical Exercise Does Not Improve Colon Inflammation in Mice Induced Lambda Carrageenan. J Med Vet. 2020;3:57. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Van Mechelen M, Martens T, Vanden Berghe P, Lories R, Gulino GR. Impact of barrier tissue inflammation and physical activity on joint homeostasis in mice. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022;61:1690-1698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hao F, Tian M, Wang H, Li S, Wang X, Jin X, Wang Y, Jiao Y, Tian M. Exercise-induced β-hydroxybutyrate promotes Treg cell differentiation to ameliorate colitis in mice. FASEB J. 2024;38:e23487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jin JJ, Ko IG, Hwang L, Kim SH, Jee YS, Jeon H, Park SB, Jeon JW. Simultaneous Treatment of 5-Aminosalicylic Acid and Treadmill Exercise More Effectively Improves Ulcerative Colitis in Mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:5076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wojcik-Grzybek D, Sliwowski Z, Kwiecien S, Ginter G, Surmiak M, Hubalewska-Mazgaj M, Chmura A, Wojcik A, Kosciolek T, Danielak A, Targosz A, Strzalka M, Szczyrk U, Ptak-Belowska A, Magierowski M, Bilski J, Brzozowski T. Alkaline Phosphatase Relieves Colitis in Obese Mice Subjected to Forced Exercise via Its Anti-Inflammatory and Intestinal Microbiota-Shaping Properties. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Szalai Z, Szász A, Nagy I, Puskás LG, Kupai K, Király A, Berkó AM, Pósa A, Strifler G, Baráth Z, Nagy LI, Szabó R, Pávó I, Murlasits Z, Gyöngyösi M, Varga C. Anti-inflammatory effect of recreational exercise in TNBS-induced colitis in rats: role of NOS/HO/MPO system. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014:925981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Liu WX, Zhou F, Wang Y, Wang T, Xing JW, Zhang S, Sang LX, Gu SZ, Wang HL. Voluntary exercise protects against ulcerative colitis by up-regulating glucocorticoid-mediated PPAR-γ activity in the colon in mice. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2015;215:24-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mazur-Bialy AI, Bilski J, Wojcik D, Brzozowski B, Surmiak M, Hubalewska-Mazgaj M, Chmura A, Magierowski M, Magierowska K, Mach T, Brzozowski T. Beneficial Effect of Voluntary Exercise on Experimental Colitis in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet: The Role of Irisin, Adiponectin and Proinflammatory Biomarkers. Nutrients. 2017;9:410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Maillard F, Vazeille E, Sauvanet P, Sirvent P, Bonnet R, Combaret L, Chausse P, Chevarin C, Otero YF, Delcros G, Chavanelle V, Boisseau N, Barnich N. Preventive Effect of Spontaneous Physical Activity on the Gut-Adipose Tissue in a Mouse Model That Mimics Crohn's Disease Susceptibility. Cells. 2019;8:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Estaki M, Morck DW, Ghosh S, Quin C, Pither J, Barnett JA, Gill SK, Gibson DL. Physical Activity Shapes the Intestinal Microbiome and Immunity of Healthy Mice but Has No Protective Effects against Colitis in MUC2(-/-) Mice. mSystems. 2020;5:e00515-e00520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wojcik-Grzybek D, Hubalewska-Mazgaj M, Surmiak M, Sliwowski Z, Dobrut A, Mlodzinska A, Wojcik A, Kwiecien S, Magierowski M, Mazur-Bialy A, Bilski J, Brzozowski T. The Combination of Intestinal Alkaline Phosphatase Treatment with Moderate Physical Activity Alleviates the Severity of Experimental Colitis in Obese Mice via Modulation of Gut Microbiota, Attenuation of Proinflammatory Cytokines, Oxidative Stress Biomarkers and DNA Oxidative Damage in Colonic Mucosa. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:2964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kolahi Z, Yaghoubi A, Rezaeian N, Khazaei M. Exercise Improves Clinical Symptoms, Pathological Changes and Oxidative/Antioxidative Balance in Animal Model of Colitis. Int J Prev Med. 2023;14:46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Özbeyli D, Berberoglu AC, Özen A, Erkan O, Başar Y, Şen T, Akakın D, Yüksel M, Kasımay Çakır Ö. Protective effect of alpha-lipoic acid, aerobic or resistance exercise from colitis in second hand smoke exposed young rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2017;44:62-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | de Oliveira Santos R, da Silva Cardoso G, da Costa Lima L, de Sousa Cavalcante ML, Silva MS, Cavalcante AKM, Severo JS, de Melo Sousa FB, Pacheco G, Alves EHP, Nobre LMS, Medeiros JVR, Lima-Junior RC, Dos Santos AA, Tolentino M. L-Glutamine and Physical Exercise Prevent Intestinal Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Without Improving Gastric Dysmotility in Rats with Ulcerative Colitis. Inflammation. 2021;44:617-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Wallace JL, Keenan CM, Gale D, Shoupe TS. Exacerbation of experimental colitis by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is not related to elevated leukotriene B4 synthesis. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:18-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Sun SP, Lu YF, Li H, Weng CY, Chen JJ, Lou YJ, Lyu D, Lyu B. AMPK activation alleviated dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis by inhibiting ferroptosis. J Dig Dis. 2023;24:213-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sun S, Chen J, Zheng M, Zhou M, Ying X, Shen Y, Hu Y, Ni K, Fan Y, Lv B. Impact of exercise on outcomes among Chinese patients with Crohn's disease: a mixed methods study based on social media and the real world. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Bottoms L, Leighton D, Carpenter R, Anderson S, Langmead L, Ramage J, Faulkner J, Coleman E, Fairhurst C, Seed M, Tew G. Affective and enjoyment responses to 12 weeks of high intensity interval training and moderate continuous training in adults with Crohn's disease. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0222060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Oliveira BRR, Santos TM, Kilpatrick M, Pires FO, Deslandes AC. Affective and enjoyment responses in high intensity interval training and continuous training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0197124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Loudon CP, Corroll V, Butcher J, Rawsthorne P, Bernstein CN. The effects of physical exercise on patients with Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:697-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ng V, Millard W, Lebrun C, Howard J. Exercise and Crohn's disease: speculations on potential benefits. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:657-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Neurath MF. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:329-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1545] [Cited by in RCA: 2087] [Article Influence: 173.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 42. | Wegierska AE, Charitos IA, Topi S, Potenza MA, Montagnani M, Santacroce L. The Connection Between Physical Exercise and Gut Microbiota: Implications for Competitive Sports Athletes. Sports Med. 2022;52:2355-2369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 43. | Klare P, Nigg J, Nold J, Haller B, Krug AB, Mair S, Thoeringer CK, Christle JW, Schmid RM, Halle M, Huber W. The impact of a ten-week physical exercise program on health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Digestion. 2015;91:239-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Cronin O, Barton W, Moran C, Sheehan D, Whiston R, Nugent H, McCarthy Y, Molloy CB, O'Sullivan O, Cotter PD, Molloy MG, Shanahan F. Moderate-intensity aerobic and resistance exercise is safe and favorably influences body composition in patients with quiescent Inflammatory Bowel Disease: a randomized controlled cross-over trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Sun Y, Wang Y, Lin Z, Zhang F, Zhang Y, Ren T, Wang L, Qiao Q, Shen M, Wang J, Song Y, Sun Y, Lin P. Irisin delays the onset of type 1 diabetes in NOD mice by enhancing intestinal barrier. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;265:130857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Zhang H, Liang J, Huang J, Wang M, Wu L, Wu T, Chen N. Exerkine irisin mitigates cognitive impairment by suppressing gut-brain axis-mediated inflammation. J Adv Res. 2025;75:843-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/