TO THE EDITOR

The intricate interplay between gut microbiota (GM) and host lipid metabolism has emerged as a pivotal factor in the pathogenesis and management of dyslipidemia, a leading modifiable risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Recent multi-omics studies underscore that GM influences lipid profiles through a spectrum of mechanisms, including short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, bile acid transformation, and signaling via host receptors such as nuclear hormone receptor farnesoid X receptor and membrane Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5. Dietary patterns, notably the Mediterranean and plant-based diets, further modulate these microbial functions, offering tangible clinical benefits.

Circadian rhythm and the GM axis

The circadian GM axis plays a crucial role in lipid regulation and dyslipidemia development[1,2]. The central circadian clock, located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, synchronizes with light-dark cycles and entrains peripheral clocks in tissues such as the liver, gut, and adipose tissue, thereby regulating metabolic processes including glucose and cholesterol metabolism[3]. The GM itself exhibits diurnal rhythmicity in composition and function, which is strongly influenced by host circadian signals[4]. In turn, microbial metabolites such as SCFAs, bile acids, and lipopolysaccharides feedback to this bidirectional communication for example, by shift work, sleep loss, or high-fat diets, which lead to circadian misalignment, gut microbial dysbiosis, and loss of rhythmicity, ultimately causing increased very low-density lipoprotein and triglyceride levels, reduced high-density lipoprotein, and heightened atherosclerotic risk[5]. Thus, circadian disruption and microbiota instability form a self-reinforcing loop that drives dyslipidemia, obesity, and metabolic syndrome, highlighting the importance of maintaining temporal synchrony through strategies such as good sleep and healthy diet, time-restricted feeding, and targeted microbiota modulation.

TRF, good sleep, and a healthy diet

Time restricted feeding (TRF), a form of intermittent fasting, is an increasingly recognized dietary strategy where all daily caloric intake is confined to a consistent window of time, usually 8-12 hours, during the body’s natural active phase, while fasting is maintained for the remaining hours, aligning eating patterns with the body’s natural circadian rhythms without necessarily reducing total caloric intake[5]. Good sleep, a healthy diet which includes high fiber, plant-based, and Mediterranean diet, along with TRF, act as trio regulators of the GM-lipid axis[6]. Mechanistically, sleep maintains circadian-microbiota synchrony, while diet shapes microbial composition and function. TRF optimizes the expression of genes involved in lipid homeostasis and enhances the rhythmic production of GM-derived metabolites like SCFAs and bile acids, which serve as crucial mediators of improvements in lipid metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and inflammation, thereby mitigating obesity-linked cardiometabolic dysfunctions[7]. Practical implementation involves consuming a healthy diet within a chosen eating window (e.g., 10 am to 6 pm) and fasting during the remaining hours, while maintaining hydration with noncaloric fluids. The efficacy of this approach is supported by a growing body of clinical research. A randomized controlled trial published by Sutton et al[8] demonstrated that a 5-week early TRF (eTRF) regimen (eating between 8 am and 4 pm) in men with prediabetes led to significant improvements in insulin sensitivity, beta-cell responsiveness, and reduced appetite even without weight loss[8]. When food is consumed late at night, it conflicts with the body’s circadian-driven insulin resistance, which can lead to higher postprandial glucose and lipid levels. Early TRF mitigates this conflict, thereby improving metabolic markers directly relevant to dyslipidemia and type 2 diabetes[8]. Furthermore, a 2020 study by Wilkinson et al[9] investigated a 10-hour TRF window in participants with metabolic syndrome. After 12 weeks, participants experienced a wide array of positive outcomes, including reduced levels of atherogenic low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, lowered blood pressure, and decreased fasting insulin[9]. Importantly, these benefits were sustained during a 12-week follow-up period, indicating good long-term adherence and tolerability[9]. By synergizing with good sleep and a healthy diet, TRF helps stabilize circadian rhythms, improve sleep quality, and optimize metabolic processes like lipid metabolism and glucose regulation[10]. This finding is critical as it suggests that TRF confers metabolic benefits beyond those attributable solely to caloric restriction. Thus, this trio is well-tolerated, non-invasive, and adaptable, making it a promising adjunct in the management of dyslipidemia and associated metabolic disorders.

Pharmacotherapy-GM crosstalk

Pharmacotherapy-microbiota crosstalk represents a rapidly evolving frontier in lipid metabolism regulation and dyslipidemia management. Lipid-lowering drugs, including statins, red yeast rice extracts, and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors, have been shown not only to modulate host lipid profiles but also to reshape gut microbial communities, thereby influencing therapeutic efficacy and side effect profiles. Statins have been shown to increase beneficial bacteria (e.g., Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus) while reducing pro-inflammatory species (e.g., Prevotella), with microbial metabolism potentially affecting drug bioavailability[11]. Red yeast rice, a natural statin source, enhances Akkermansia muciniphila abundance, which correlates with improved metabolic health, and reduces Clostridium species linked to dyslipidemia[12]. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors, although primarily systemic, may indirectly alter microbiota via bile acid metabolism shifts[13]. Additionally, microbiota-derived metabolites, such as SCFAs and trimethylamine-N-oxide, further modulate lipid homeostasis, suggesting potential for microbiome-targeted adjunct therapies[14]. Understanding these interactions could lead to personalized dyslipidemia treatments leveraging microbial biomarkers and postbiotic interventions, which include beneficial microbial products or components such as SCFA, cell wall fractions, or metabolites rather than live microorganisms (probiotics) or substrates that feed them (prebiotics). Although no microbiota-guided prescribing algorithms are yet in clinical use, emerging research in pharmacomicrobiomics and machine-learning models points to a future of precision lipid-lowering therapy. The study by Zimmermann et al[15] provides fundamental evidence that an individual’s unique gut microbiome can directly alter drug bioavailability and effects, a core tenet for any future prescribing algorithm[15]. Such frameworks would integrate baseline microbiome composition (e.g., trimethylamine-N-oxide-producing potential, Akkermansia abundance), host genetics (e.g., apolipoprotein E genotype), clinical and metabolomic data, and prior drug responses to generate individualized recommendations[16,17]. However, these approaches are still at the proof-of-concept stage and require validation in large, longitudinal, multi-omics clinical studies. Moreover, antibiotic exposure is indeed a major, yet under-recognized, modifier of GM and lipid homeostasis. Broad-spectrum antibiotics can deplete SCFA-producing taxa and alter bile-acid metabolism, potentially worsening lipid profile, whereas low-level environmental exposures may exert sex-dependent effects and even raise certain SCFAs under high-fat diet conditions[18,19]. Beyond altering SCFAs, antibiotic exposure reshapes bile-acid pools, microbial cholesterol conversion, and gut barrier integrity, and can modify the microbial enzymes that determine lipid-lowering drug metabolism. These examples illustrate how GM could eventually inform drug selection and dosing in dyslipidemia management.

Population-specific microbial signatures

Enterotypes are broadly defined patterns of gut microbial community composition dominated by certain key genera (e.g., Bacteroides, Prevotella, Ruminococcus)[20]. Emerging evidence suggests that GM varies significantly across populations due to genetic, dietary, and environmental factors, influencing statin efficacy and side effects. Non-Western, agrarian communities typically harbor Prevotella-dominant enterotypes, shaped by fiber-rich plant-based diets, whereas Western populations more often exhibit Bacteroides-dominant profiles, linked to high-fat, low-fiber dietary patterns[20]. These population-specific configurations may have important implications for statin metabolism and lipid-lowering efficacy, since microbial composition not only affects drug biotransformation but also interacts with host lipid and bile acid pathways. The observation that obesity-associated dysbiosis, particularly the pro-inflammatory Bacteroides 2 enterotype, is attenuated in statin-treated individuals highlights the need to investigate whether such microbiota-modulating effects are consistent across diverse ethnic and geographic cohorts[21]. A precision medicine framework integrating microbiome stratification with statin therapy could therefore optimize dyslipidemia management while minimizing inter-individual variability in treatment response.

Beyond statins and metformin already discussed by Lv et al[1], other interventions demonstrate population-specific microbiome dependencies. For instance, dietary fiber supplementation enriches SCFA-producing taxa such as Roseburia and Prevotella, but its metabolic benefits vary markedly across populations depending on baseline microbial configurations[22]. Evidence suggests that insoluble cereal fibers, although less emphasized, may exert stronger protective effects against chronic inflammation and lipid dysregulation compared with soluble fibers. Moreover, the high-fructose content of many soluble fiber–rich fruits could blunt potential benefits, particularly in populations with already elevated sugar intake. These nuances highlight that precision dietary strategies should move beyond “total fiber intake” and instead consider fiber subtype, microbiota responsiveness, and population context to optimize metabolic outcomes[23]. Together, these examples highlight the need to contextualize microbiota-targeted strategies for dyslipidemia within diverse ethnic and dietary backgrounds, moving toward a precision-microbiome framework for global translation.

Functional microbiota profiling

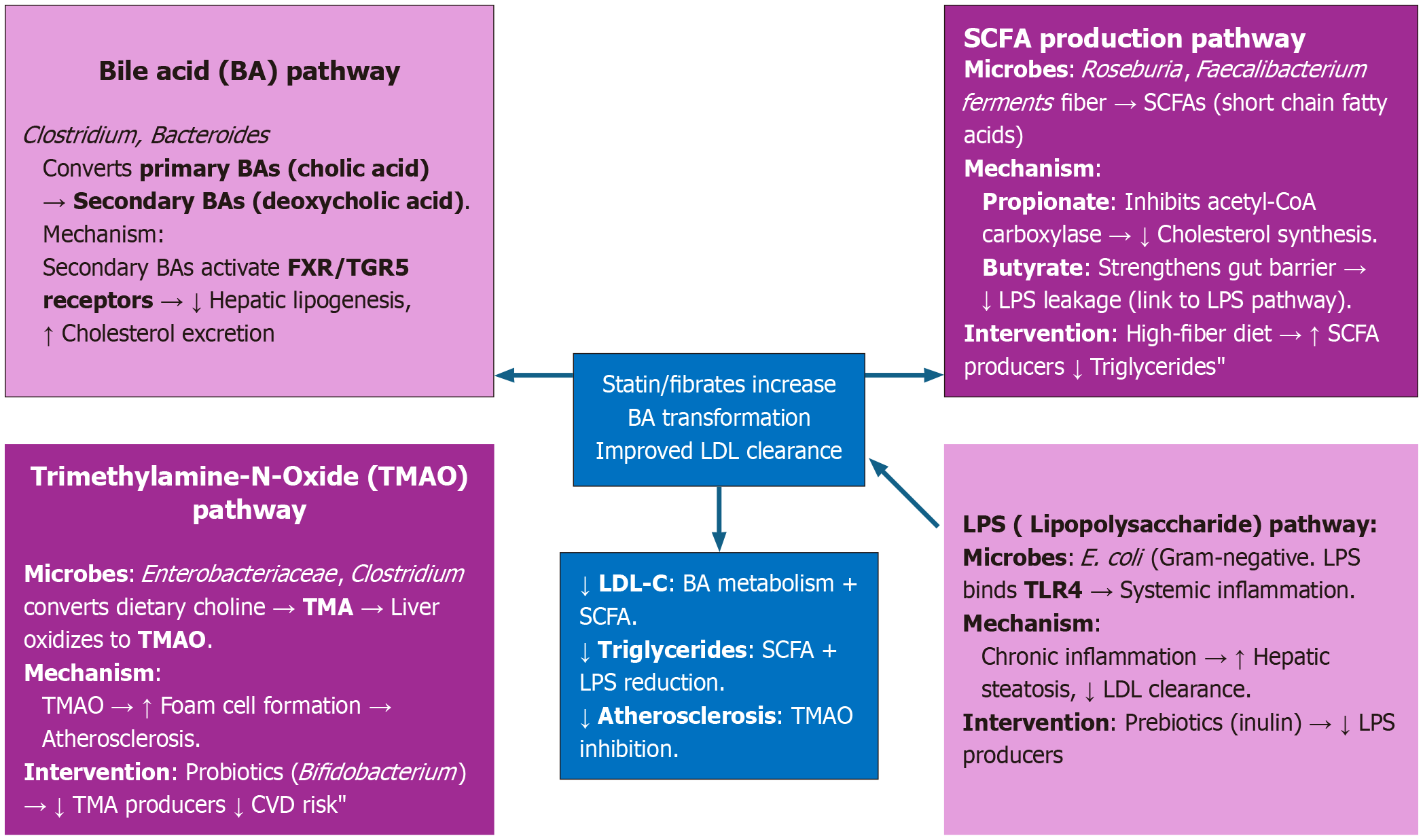

Functional microbiome profiling, which examines microbial genes, pathways, and metabolites, provides a powerful tool for understanding and managing dyslipidemia. Unlike taxonomic profiling (which identifies “who is there”), functional profiling reveals “what the microbiota is doing” and how it interacts with host physiology, diet, and lipid-lowering therapies.Figure 1 shows key functional pathways in dyslipidemia[24-27]. To study these pathways, researchers use shotgun metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, metabolomics, and gnotobiotic models[28,29]. Diet-drug-microbiome synergy further enhances treatment efficacy, exemplified by resistant starch boosting Bifidobacterium to improve statin-mediated low-density lipoprotein reduction, and polyphenol-rich diets increasing Akkermansia to optimize bile acid metabolism[30]. Additionally, microbial biomarkers, e.g., β-glucuronidase activity, low/high, and type of SCFA producers, enable precision therapy[31,32]. Looking ahead, postbiotic therapies (e.g., direct SCFA/betulinic acid analog delivery) and artificial intelligence-driven multi-omics integration (combining microbiome, metabolome, and genomics) hold transformative potential for advancing personalized dyslipidemia management.

Figure 1 Key functional pathways in dyslipidemia.

BA: Bile acid; FXR: Farnesoid X receptor; TGR5: Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein; SCFAs: Short-chain fatty acids; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; TMAO: Trimethylamine-N-Oxide; TMA: Trimethylamine; CVD: Chemical vapor deposition; LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Antibiotic exposure, gut-liver axis and bile-acid pool shifts: Antibiotics suppress bile-salt hydrolase-producing bacteria (Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Clostridium cluster XIVa), leading to reduced deconjugation of primary bile acids and altered secondary bile acid composition: (1) Bile acids regulate farnesoid X receptor and Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5; changes in their pool affect cholesterol absorption, hepatic lipogenesis, and low-density lipoprotein-receptor expression[19]; (2) Altered cholesterol absorption and fecal sterol excretion: By changing bile acid deconjugation and microbial cholesterol-to-coprostanol conversion, antibiotics can increase or decrease intestinal cholesterol absorption and fecal cholesterol loss. Direct impact on plasma cholesterol levels[33]; (3) Loss of microbial enzymes modulating drugs: Antibiotics can deplete microbes producing β-glucuronidase, sulfatases, or reductases that activate/inactivate lipid-lowering drugs. This may alter statin bioavailability, toxicity, or efficacy (the “pharmacomicrobiomics” angle)[34]; (4) Increased gut permeability and endotoxemia: Dysbiosis caused by antibiotics can thin the mucus layer and reduce tight-junction integrity, increasing systemic lipopolysaccharide. Low-grade endotoxemia promotes hepatic very-low-density lipoprotein secretion, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia[35]; and (5) Sex-dependent metabolic outcomes: Some antibiotics under a high-fat diet produce weight gain only in males; hormonal milieu interacts with dysbiosis. Sex hormones modulate lipid.

Conclusion

Interventions like time-restricted feeding, resistant starch, and polyphenol-rich diets demonstrate that synchronizing diet and lifestyle with microbiota functionality can potentiate the efficacy of lipid-lowering drugs such as statins and fibrates. Moreover, precision strategies that integrate microbial profiling identifying enterotypes such as Bacteroides 2 or Akkermansia enrichment may transform dyslipidemia management from a generalized to a personalized approach. Future research should prioritize longitudinal, multi-omics studies that capture temporal dynamics and interindividual variability, enabling translation of microbiome science into clinically actionable, population-specific therapies.