Published online Dec 28, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i48.112683

Revised: September 17, 2025

Accepted: November 12, 2025

Published online: December 28, 2025

Processing time: 146 Days and 11.5 Hours

Due to their significantly lower incidence than colorectal polyps and macroscopic features resembling those of hyperplastic polyps, rectal neuroendocrine tumors (rNETs) are frequently misdiagnosed and resected as polyps. To date, no reports have been written on the application of artificial intelligence for assisting in the white-light endoscopy of rNETs.

To establish a neuroendocrine tumor lesion detection algorithm based on the YOLOv7 model and evaluate the performance of the algorithm in identifying neuroendocrine tumors.

In total, 137748 white-light endoscopic images were collected in this study, including 2232 images of rNET, 4429 images of submucosal lesions other than rNET, 42563 images of polyps, and 88593 images of normal mucosa. All the images were randomly divided into a training set, a validation set, and a test set. To evaluate the ability of the algorithm to diagnose rNETs, we selected 1578 images to form the test set. The performance of the algorithm was compared with that of endoscopists at different levels.

The accuracy of the algorithm in identifying rNET from all the images was 97.8%, the sensitivity was 72.6%, the specificity was 99.7%, the positive predictive value was 93.9%, and the negative predictive value was 98.1%.

Our model, which was based on YOLOv7, could effectively detect rNET lesions, which was better than that of most endoscopists.

Core Tip: Due to significantly lower incidence compared to colorectal polyps and macroscopic features resembling hyper

- Citation: Liu K, Wang ZY, Yi LZ, Li F, He SH, Zhang XG, Lai CX, Li ZJ, Qiu L, Zhang RY, Wu W, Lin Y, Yang H, Liu GM, Guan QS, Zhao ZF, Cheng LM, Dai J, Bai Y, Xie F, Zhang MN, Chen SZ, Zhong XF. Artificial intelligence-assisted diagnosis of rectal neuroendocrine tumors during white-light endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(48): 112683

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i48/112683.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i48.112683

Rectal neuroendocrine tumors (rNETs) are subepithelial lesions derived from neuroendocrine cells[1]. These tumors have a relatively low incidence rate, accounting for approximately 1%-2% of all rectal tumors and 20% of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors[2,3]. rNETs are low malignant potential tumors but still face the risk of metastasis[4]. When discovered, rNETs are usually small (diameter < 10 mm) and are 5-10 cm from the anal verge[5]. Under white-light endoscopy, rNETs are typically manifested as small yellowish submucosal lesions with smooth intact overlying mucosa, similar to that of hyperplastic polyps[6].

Owing to their much lower incidence rate than colorectal polyps and their small sizes and macroscopic features resembling those of hyperplastic polyps, rNETs are often misdiagnosed and removed as polyps in clinical practice. The incomplete resection rate tends to increase when rNETs (submucosal lesions) are treated with polypectomy. This technique is primarily designed for removing mucosal layer lesions. This process often leads to the need for additional salvage treatments or repeated imaging and endoscopic follow-ups[7].

The endoscopic findings of rNETs are varied. In addition to the typical white-light endoscopy findings mentioned above, subpedunculated lesions, superficial congestion, central depressions, surface erosion, and ulcers may appear[8]. Given that rNETs are rare tumors, their diverse endoscopic appearances increase the likelihood of misidentification. When rNETs are clinically suspected, subsequent endoscopic ultrasound is usually recommended and can generally confirm the diagnosis. Additionally, endoscopic ultrasound can assess the size, invasion depth of the tumor, and the presence of pararectal lymph node metastasis, all of which are clinically significant for selecting appropriate treatment strategies[9]. Therefore, despite rNETs being subepithelial lesions, timely identification or screening of suspicious lesions during white-light endoscopy remains crucial for choosing the most suitable treatment approach.

Owing to the rarity and variety of endoscopic findings of rNETs, the diagnostic experience of a single endoscopist is significantly limited, particularly for atypical lesions, which are prone to misidentification. Computer-aided detection and diagnosis systems have shown great potential in gastrointestinal endoscopy. However, to our knowledge, no reports have been made to date on the application of artificial intelligence (AI) for assisting in the white-light endoscopy of rNETs. YOLOv7, an object detection algorithm proposed in 2022, has shown promise in improving the detection of laterally spreading tumors[10]. In surgical tool tracking, YOLOv7 can generate dynamic trajectories, thereby offering increasingly adaptable and precise support for minimally invasive surgical procedures[11]. Furthermore, this model has potential for assisting surgeons in identifying critical anatomical landmarks during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which may reduce the incidence of bile duct injury[12]. In this study, an image analysis model for rNETs based on the YOLOv7 algorithm is developed that can efficiently assist endoscopists in detecting rNETs during white-light endoscopy.

A total of 11037 patients who had a colonoscopy at the People’s Hospital of Leshan and Nanfang Hospital of Southern Medical University from January 2019 to December 2023 were included in this study. Clinical information and endoscopic images were obtained. The patients ranged in age from 10-93 years, and the mean age was 56 ± 12.556 years. There were 6615 male patients (59.9%) and 4422 female patients (40.1%). Among these patients, 373 had rNETs, 1003 had submucosal lesions other than rNETs, 9340 had polyps, and 410 were otherwise healthy without any lesions. The colonoscopes used in the image collection process were CV-260/290SL (Olympus Optical from Japan) and VP-4450HD (Fujifilm from Japan). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the People’s Hospital of Leshan (approval No. LYLL2023ky066) and Nanfang Hospital of Southern Medical University (approval No. NFEC-2024-333).

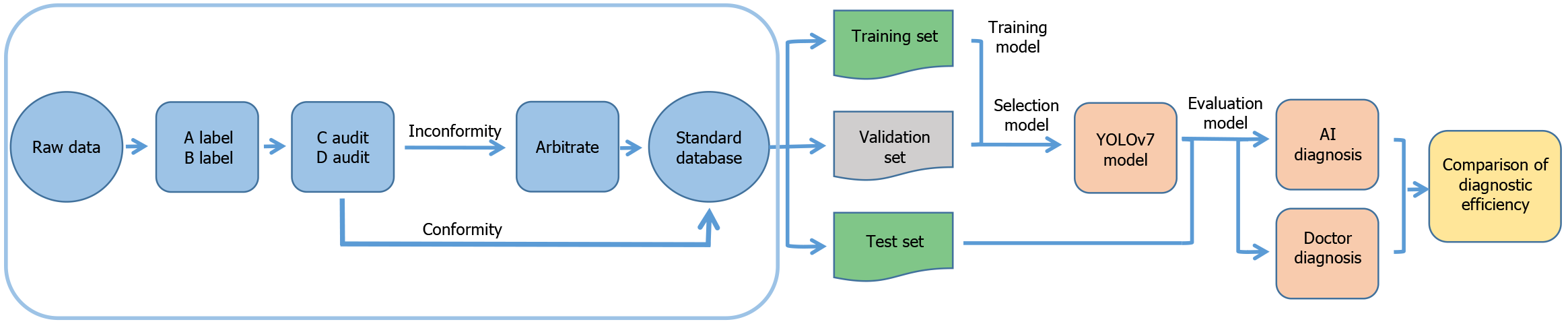

Two novice endoscopists (each with < 5 years of experience in colonoscopy) classified the endoscopic images on the basis of the endoscopy report and pathological results and outlined the extent of the lesion with a rectangular box. Two senior endoscopists (each with 5-9 years of experience in colonoscopy) audited the classification results. If the assessments of the 2 senior endoscopists were consistent, the classification result was considered as the gold standard. In cases of disagreement, the decision was submitted to an expert endoscopist (≥ 10 years of experience in colonoscopy) for arbitration, and the result was used as the gold standard. Ultimately, a total of 137748 white-light endoscopy images were collected from the standard database in this study (Supplementary Table 1).

The construction and validation of the YOLOv7 model are illustrated in Figure 1. The detection process of YOLOv7 involves the following steps. First, the input image was first resized to the required value and then normalized. Multiscale features were subsequently extracted through the backbone network. These features were first fused and processed in the neck and then transmitted to the head of the network. The location and classification of the object were predicted, and the corresponding bounding boxes were generated. Finally, the nonmaximum suppression algorithm was used to obtain the final prediction results.

In this study, eight NVIDIA RTX 4090D graphics cards were used for fine-tuning the YOLOv7 model on the basis of the annotated endoscopy dataset. The loss function of the model consisted of three parts, namely, positioning loss, confidence loss and class loss, which were used to measure the differences between the predicted bounding box and the true bounding box in terms of position, confidence and class, respectively. The comprehensive effect of these losses allowed the model to identify lesions with relatively high accuracy. To increase the robustness of the model, various data enhancement techniques, including random cropping, dithering and horizontal flipping, were applied to increase the diversity of the training data. The key hyperparameters used in this study are listed in Table 1.

| Hyperparameters | Value |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Batch_size | 32 |

| Epochs | 50 |

| Image_size | 640 × 640 |

| Learning_rate | 5e-4 |

| Weight_decay | 5e-4 |

To evaluate the ability of the YOLOv7 model to diagnose rNETs, we selected 1578 images to form the test set. The performance of the YOLOv7 model was compared with that of 2 expert endoscopists, 2 senior endoscopists, and 2 novice endoscopists who did not participate in the construction of the standard database. During the test, the endoscopist or YOLOv7 model was asked to determine whether the image contained a lesion. For “Yes”, the endoscopist or YOLOv7 model outlined the extent of the lesion using a rectangular box with a label indicating rNET, SMT (submucosal lesions other than rNET), or polyp in the image. For “No”, the image was classified as normal mucosa. Furthermore, we conducted a comparative analysis of the performance of the YOLOv5 and YOLOv7 models in the diagnosis of rNETs. We employed YOLOv5 and YOLOv7 models to detect images of rNETs and constructed receiver operating characteristic curves to assess the classification performance of the respective models.

The criteria for determining correct classification were as follows: Considering that this study involved the identification of polyps with clear boundaries and submucosal tumors with unclear boundaries, to comprehensively evaluate the diagnostic ability of endoscopists and AI for rNETs, we established two criteria to determine whether the predictions made by either endoscopists or AI on the images were correct.

Criterion 1: The image was taken as the unit. According to a comparison with the gold standard in the standard database, we determined whether the classification of the image by doctors or AI was correct. If the classification was correct, the prediction was deemed correct; otherwise, it was deemed incorrect.

Criterion 2: The lesion was taken as the unit. In comparison with the gold standard in the standard database, and on the basis of the correct classification of the image, if the intersection over union between the predicted box and the standard box in the standard database was greater than 0.2, the prediction was deemed correct; otherwise, it was deemed incorrect. The intersection over union was calculated as the intersection area of the prediction box and the real box divided by the union area of the prediction box and the real box.

To analyze the prediction results, we compared the performance characteristics of the AI and endoscopists across three progressively advanced levels. The first level involved lesion detection. The second level was focused on identifying submucosal lesions from the detected lesions, whereas the third level was concentrated on recognizing rNETs from the identified submucosal lesions. Finally, we compared the accuracy rates of AI and endoscopists in identifying rNETs from all the images within the test set.

The precision [positive predictive value (PPV)], recall, F1 score and negative predictive value (NPV) parameters were selected as the evaluation metrics for the endoscopists and models. Precision was defined as the ratio of correctly predicted positive observations to the total number of predicted positive observations. Recall was the ratio of correctly predicted positive observations to all observations in the actual class. The F1 score was calculated as the weighted average of precision and recall. The NPV was the ratio of correctly predicted negative observations to the total number of predicted negative observations. These metrics could be formulated as follows: True positive refers to instances where the actual condition is positive, and the model correctly identifies these instances as positive. False positive refers to cases where the model incorrectly classifies a negative instance as positive. False negative refers to cases where the actual condition is positive but the model incorrectly classifies it as negative. True negative refers to instances where the actual condition is negative and the model correctly identifies these instances as negative.

Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests with a significance level of 0.05 were used to compare differences in the accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and PPV and NPV of the AI model and endoscopists. All calculations were performed using SPSS 20 (IBM, Chicago, IL, United States).

The trained YOLOv7 model achieved excellent performance in identifying rNETs, with precision, recall, and F1 scores of 0.991, 0.988, and 0.990, respectively, in the training set and 0.910, 0.831, and 0.868, respectively, in the validation set (Table 2).

| Dataset | Precision | Recall | F1 |

| Training set | 0.991 | 0.988 | 0.990 |

| Validation set | 0.910 | 0.831 | 0.868 |

Comparison of the model and endoscopists in the detection of lesions: In terms of lesion detection, when the image was taken as the unit, the model demonstrated superior accuracy, specificity, and PPV compared with the average values across all endoscopists (0.984 vs 0.966, 0.997 vs 0.955, and 0.995 vs 0.928, respectively). However, the sensitivity and NPV of the model were slightly lower (0.961 vs 0.984 and 0.979 vs 0.991, respectively) (Table 3). When the lesion was taken as the unit, the F1 score of the model was higher than the average value across all the endoscopists (0.957 vs 0.931) (Supplementary Table 2).

| Group | PPV | Sensitivity | NPV | Specificity | Accuracy |

| Expert1 | 0.981 (0.008)2 | 0.966 (0.004) | 0.980 (0.002) | 0.990 (0.005) | 0.981 (0.001) |

| Senior1 | 0.901 (0.021)a | 0.993 (0.000)a | 0.996 (0.000)a | 0.938 (0.014)a | 0.958 (0.010) |

| Novice1 | 0.901 (0.009)a | 0.993 (0.000)a | 0.996 (0.000)a | 0.938 (0.006)a | 0.958 (0.004)a |

| Mean-doctor | 0.928 (0.043)a | 0.984 (0.014)a | 0.991 (0.008)a | 0.955 (0.028)a | 0.966 (0.013)a |

| AI | 0.995 | 0.961 | 0.979 | 0.997 | 0.984 |

Comparison of the model and endoscopists in the detection of submucosal lesions: In terms of the identification of submucosal lesions from the detected lesions, when the image was taken as the unit, the accuracy, specificity, and PPV of the model were greater than the average values of the endoscopists (0.971 vs 0.943, 0.987 vs 0.958, and 0.939 vs 0.833, respectively), whereas there was no significant difference in the sensitivity or NPV between the model and endoscopists (Table 4). When the lesion was taken as the unit, the precision of the model was greater than the average accuracy of the endoscopists (0.981 vs 0.870) (Supplementary Table 3).

| Group | PPV | Sensitivity | NPV | Specificity | Accuracy |

| Expert1 | 0.909 (0.007)2 | 0.891 (0.002)a | 0.976 (0.001) | 0.980 (0.001)a | 0.962 (0.001)a |

| Senior1 | 0.828 (0.030) | 0.911 (0.015) | 0.980 (0.004) | 0.956 (0.009) | 0.948 (0.011) |

| Novice1 | 0.762 (0.014)a | 0.839 (0.002)a | 0.962 (0.001)a | 0.940 (0.002)a | 0.919 (0.001)a |

| Mean-doctor | 0.833 (0.068)a | 0.880 (0.034) | 0.972 (0.008) | 0.958 (0.018)a | 0.943 (0.020)a |

| AI | 0.939 | 0.909 | 0.979 | 0.987 | 0.971 |

Comparison of the model and endoscopists in the diagnosis of rNETs from detected submucosal lesions: When rNETs were diagnosed from the detected submucosal lesions, when the image was taken as the unit, the accuracy, specificity, sensitivity, and PPV of the model were greater than the average values across the doctors (0.977 vs 0.945, 0.994 vs 0.972, 0.981 vs 0.967, and 0.940 vs 0.721, respectively), whereas there was no significant difference in the NPV between the model and the doctors (Table 5). When the lesion was taken as the unit, the precision and F1 score of the model were greater than the average values of the doctors (0.940 vs 0.717 and 0.864 vs 0.683, respectively) (Supplementary Table 4).

| Group | PPV | NPV | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy |

| Expert1 | 0.855 (0.046)2 | 0.778 (0.047) | 0.977 (0.006) | 0.986 (0.008) | 0.967 (0.001)a |

| Senior1 | 0.675 (0.001)a | 0.697 (0.071) | 0.964 (0.008) | 0.962 (0.001)a | 0.932 (0.009) |

| Novice1 | 0.635 (0.071) | 0.573 (0.016)a | 0.960 (0.001)a | 0.968 (0.012) | 0.935 (0.012) |

| Mean-doctor | 0.721 (0.111)1 | 0.683 (0.100) | 0.967 (0.009)1 | 0.972 (0.013)1 | 0.945 (0.018)1 |

| AI | 0.940 | 0.797 | 0.981 | 0.994 | 0.977 |

Comparison of the model and endoscopists in the identification of rNETs from all the images: When the image was taken as the unit, the accuracy, specificity, and PPV of the model were better than the average values of the doctors (0.978 vs 0.942, 0.997 vs 0.964, and 0.939 vs 0.589, respectively), whereas there was no significant difference in the sensitivity or NPV between the model and the doctors (Table 6). When the lesion was taken as the unit, the precision and F1 of the model for identifying rNETs were greater than the average values of the endoscopists (0.940 vs 0.582 and 0.821 vs 0.591, respectively) (Supplementary Table 5).

| Group | PPV | Sensitivity | NPV | Specificity | Accuracy |

| Expert1 | 0.808 (0.006)2,a | 0.755 (0.027) | 0.982 (0.002) | 0.987 (0.001)1 | 0.972 (0.001)a |

| Senior1 | 0.473 (0.047)a | 0.778 (0.033) | 0.983 (0.003) | 0.938 (0.009)1 | 0.927 (0.011)a |

| Novice1 | 0.487 (0.098)a | 0.392 (0.087)a | 0.956 (0.005)a | 0.968 (0.019) | 0.929 (0.011)a |

| Mean-doctor | 0.589 (0.176)a | 0.642 (0.199) | 0.974 (0.014) | 0.964 (0.024)a | 0.942 (0.024)a |

| AI | 0.939 | 0.726 | 0.981 | 0.997 | 0.978 |

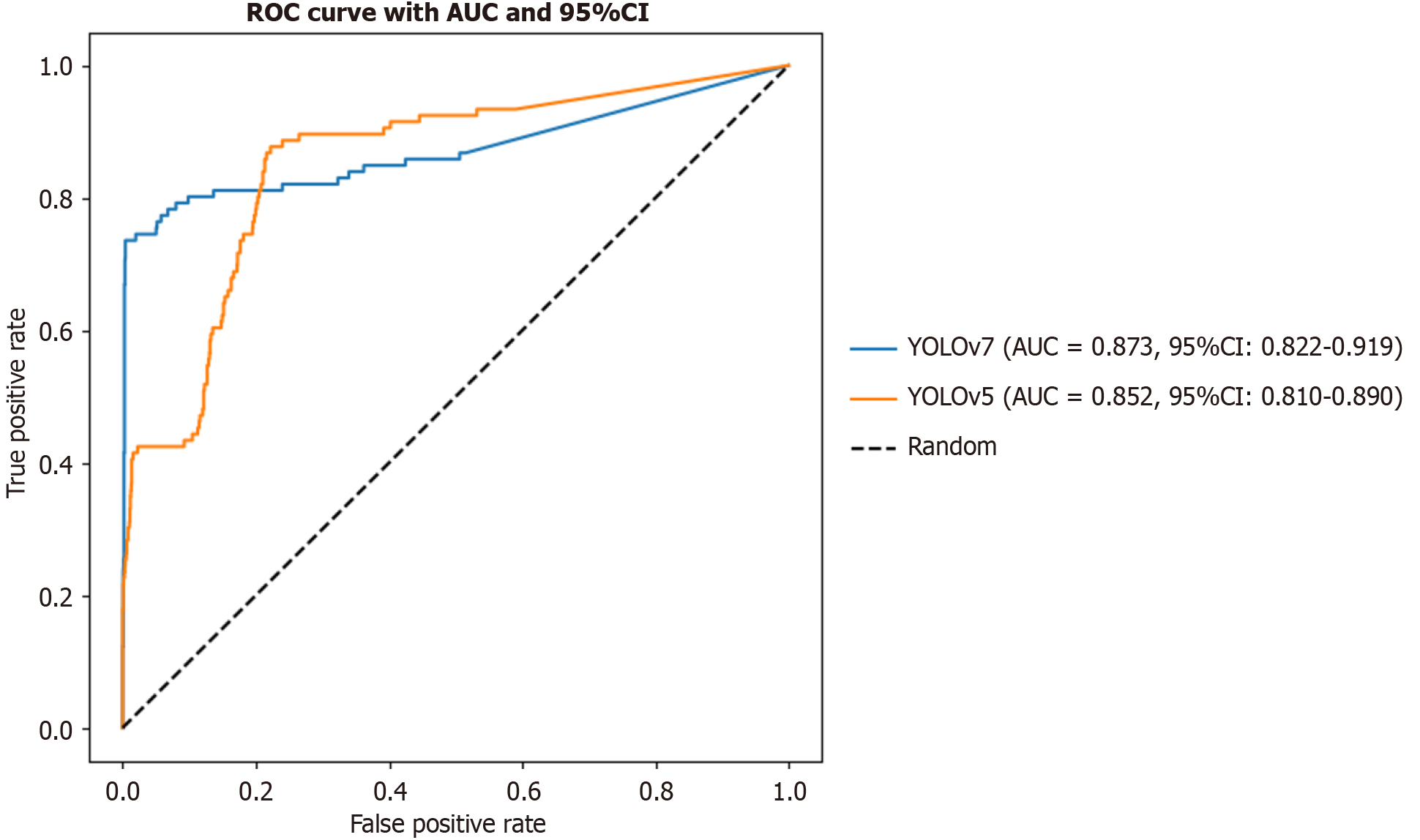

Comparison of different methods for identifying rNETs from all images: When the receiver operating characteristic curves were compared, YOLOv7 demonstrated a significantly higher true positive rate than YOLOv5 across most false positive rate (FPR) intervals, particularly in the low-FPR region where FPR < 0.2. This finding suggested that YOLOv7 was more effective at identifying positive samples while maintaining a lower rate of false positives, thereby leading to superior classification performance. A further comparison based on the area under the curve (AUC) index revealed that YOLOv7 achieved an AUC value of 0.873 (95% confidence interval: 0.822-0.919), outperforming YOLOv5, which had an AUC of 0.852 (95% confidence interval: 0.810-0.890) (Figure 2). Both models significantly exceeded the performance of a random classifier (AUC = 0.5), confirming their reliability in the detection of rNETs. Overall, YOLOv7 outperformed YOLOv5 overall, indicating its advantages in enhancing both sensitivity and specificity (Table 7).

| Method | Precision | Recall | F1 |

| YOLOv7 | 0.940 | 0.729 | 0.821 |

| YOLOv5 | 0.927 | 0.720 | 0.810 |

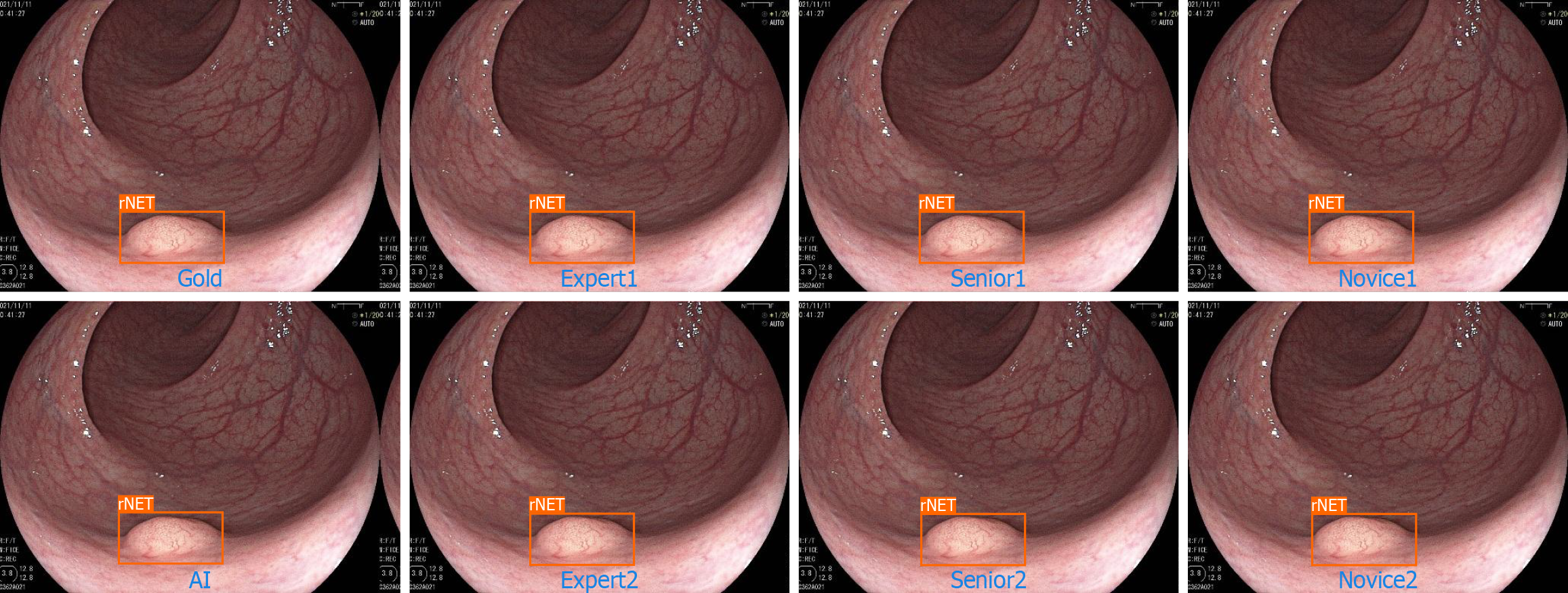

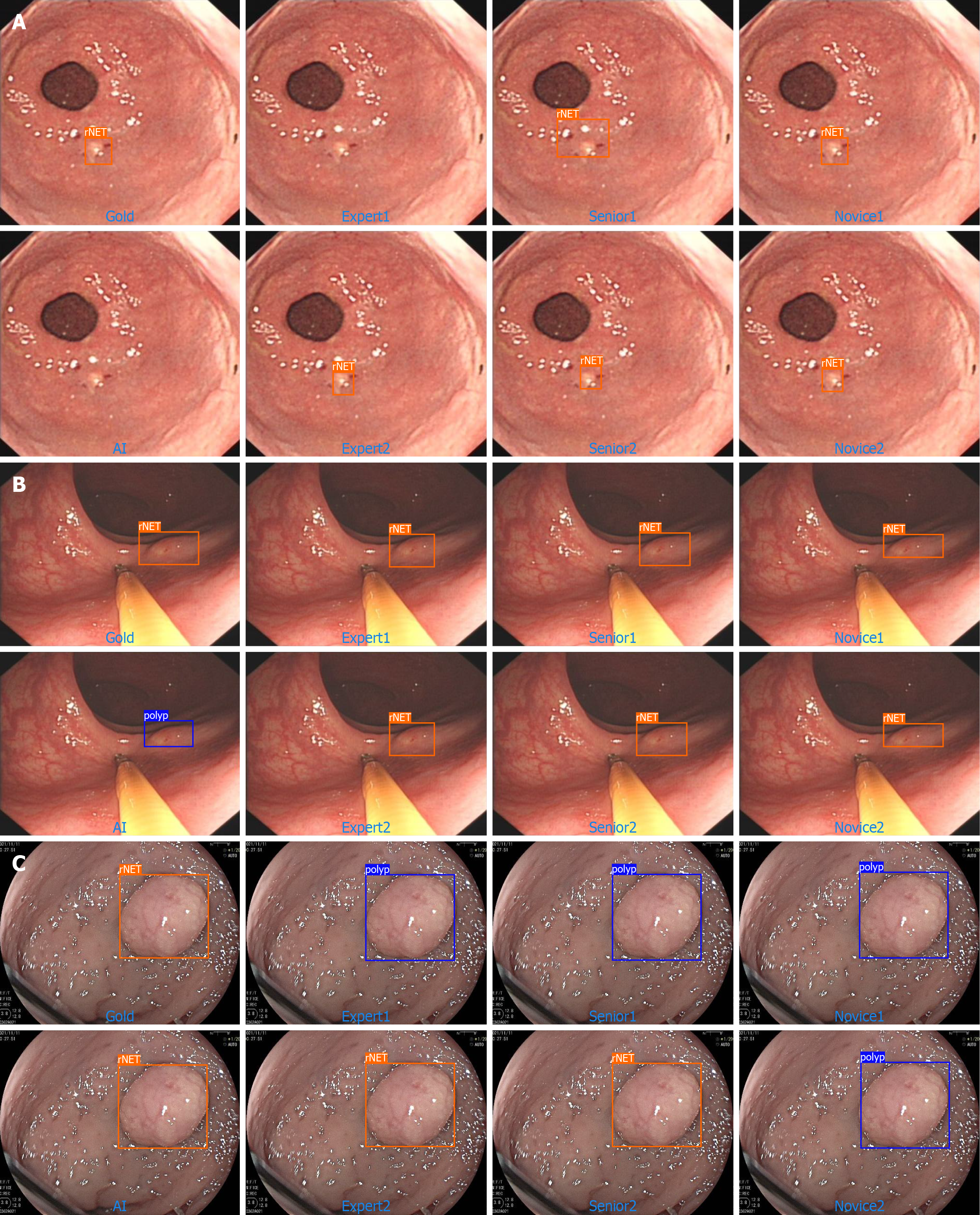

In this section, we listed four situations identified by the AI model: First, rNET could be accurately identified by an algorithm and endoscopists (total right; Figure 3). The second type was an rNET that neither the AI algorithm nor endoscopists could accurately identify (error both; Figure 4A). The third type was the rNET that could not be accurately identified by the AI algorithm (error-AI; Figure 4B). In the fourth type, endoscopists failed to accurately identify (error-endoscopist; Figure 4C). Although our AI diagnostic model demonstrated promising diagnostic outcomes, the various endoscopic features of rNETs presented challenges for AI learning, leading to occasional missed or incorrect diagnoses. To address these limitations, we plan to enhance the model training regime by incorporating a greater range of rNETs.

Endoscopy serves as a critical method for screening and treating gastrointestinal tumors. When integrated with AI, endoscopy demonstrates significantly enhanced accuracy, consistency, and classification capability in detecting lesions within endoscopic images. Moreover, endoscopy has alleviated the diagnostic workload of clinicians and reduced the rate of missed diagnoses.

In recent years, numerous AI-assisted models have been developed for research on gastric cancer (GC), esophageal cancer, and colorectal cancer. Niikura et al[13] evaluated and compared the diagnostic accuracy of AI with that of expert endoscopists in analyzing GC images obtained through gastroscopy. The diagnostic concordance rate of the AI group for GC was 99.87% (747/748 images), which was greater than that of the expert endoscopist group at 88.17% (693/786 images), which is an 11.7% difference. These findings demonstrate that AI is not inferior to expert endoscopists in the diagnosis of GC. Ikenoyama et al[14] evaluated an AI model trained on a dataset comprising 6634 white-light endoscopy and narrow-band imaging (NBI) images for accurate prediction of Lugol-voiding lesions without staining procedures. Among the 595 patients included in the study, the sensitivity of the AI system was 84.4%, the specificity was 70.0%, and the overall accuracy was 76.4%. These performance metrics surpassed those of nine out of ten experienced endoscopists, who achieved a sensitivity of 46.9%, specificity of 77.5%, and accuracy of 63.9%. These results suggest that the AI system can predict the characteristics of multiple Lugol-voiding lesions with high sensitivity from images without iodine staining. A prospective, randomized controlled study comprising 1058 patients, as reported by Wang et al[15], de

Although extensive research has been conducted on the application of AI in the auxiliary diagnosis of gastrointestinal tumors, the current focus remains predominantly on tumors with higher incidence rates, such as GC, esophageal cancer, and colorectal cancer (particularly GC). A recent review on AI-assisted diagnosis of gastrointestinal tumors indicated that 52% of the studies were focused on GC[16]. In contrast, research on less common tumors, such as rNETs, is limited. This imbalance in research attention partially restricts the broad application of AI in the field of gastrointestinal oncology. rNETs are rare. Although the prevalence of rNETs has increased in recent years, this increase may be attributed to the popularization of colon cancer screening and the increasing number of young patients undergoing colonoscopy for various symptoms rather than an actual increase in rNETs in the population[17,18]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the assistance of AI in the diagnosis of rNETs under white-light endoscopy.

The long-term survival of most patients with rNETs is favorable[19]. However, all rNETs possess metastatic potential, which increases with increasing tumor size. Scholars have reported that the lymph node metastasis rates for tumors with a diameter ≤ 10 mm are in the range of 0%-10.3%, whereas for tumors with diameters in the range of 10-20 mm, the rates are in the range of 25%-96.9%[20-22].

The main challenge in diagnosing rNETs is their tendency to be misidentified as polyps, which can lead to the use of inappropriate resection techniques[23]. Lesions with a preoperative diagnosis or suspicion of being rNETs have a much higher complete resection rate than those treated with polyp resection do[24]. Therefore, the timely identification of suspicious lesions during colonoscopy is a key factor affecting the management of rNETs.

Although numerous online resources are available to assist endoscopists in learning the characteristics of rNETs, misdiagnoses still frequently occur because of their low incidence rate and similarities in appearance to those of polyps[25]. In a multicenter study, only 18% of rectal NETs were diagnosed or suspected during indexing, resulting in 76% of cases having incomplete resection during the first procedure[26].

Given that the diagnosis of rNETs under white-light endoscopy involves distinguishing them from polyps and other submucosal tumors, the model must be trained to recognize not only rNETs but also colorectal polyps and other submucosal lesions. In our study, a total of 137748 white-light endoscopy images were collected, comprising 2232 images of rNETs, 4429 images of non-rNET submucosal lesions, 42563 images of polyps (including 69 images showing both polyps and submucosal tumors), and 88593 images of normal mucosa. A robust predictive model was developed and trained using the YOLOv7 algorithm. The trained YOLOv7 model demonstrated excellent performance in identifying rNETs, achieving accuracy rates exceeding 90% in both the training and validation datasets. This high accuracy in detecting rNETs was achieved by leveraging the ability of the model to accurately identify polyps and other submucosal tumors. Our prior research has confirmed that the model exhibits high precision in identifying laterally spreading tumors[10]. Thus, the identification of rNETs represents an extension of the diagnostic capabilities of the model.

We subsequently evaluated the ability of endoscopists and AI to diagnose rNETs using the test set. We compared the AI with that of three groups of endoscopists at different levels, which could better reflect the clinical reality. Since polyps have clear boundaries and submucosal tumors do not, we adopted two criteria to determine whether the predictions made by endoscopists or AI on the images were correct, thereby enhancing the accuracy of assessing the diagnostic abilities of the model and the doctors for each image. Afterward, we compared the diagnostic performance of the model with that of the endoscopists across three progressive logical levels. Whether assessed by images or lesions, the model demonstrated an accuracy rate exceeding 90% at all three levels, surpassing the performance of most endoscopists.

This study has several limitations. First, the location of the lesions is not included in this study. In actual clinical practice, if the examination is limited to the rectum, endoscopists may have an increased tendency to diagnose atypical rNETs. Second, although cases are collected from multiple centers, owing to the rarity of rNETs, only 373 rNET cases are included in this study, which may limit the adequacy of model evaluation. This finding can explain why some of the results in our study show trends but lack statistical significance. Additionally, no NBI or bioluminescence imaging images are included, potentially leading to incomplete assessment of the lesions. Today’s advanced endoscopes equipped with image enhancement technologies have significantly enhanced the sensitivity and specificity of endoscopic diagnosis for gastrointestinal lesions. Enhancement techniques such as NBI serve as valuable tools for characterizing rNETs, particularly in identifying atypical lesions[27]. In future studies, we plan to further annotate the NBI and bioluminescence imaging images of rNET to improve our dataset, which should improve the ability of the model in diagnosing rNETs. Third, evaluating the performance of AI systems in a real environment is highly important[28]. The model proposed in this study was tested only on static images and not on real-time video. In actual clinical practice, factors such as intestinal peristalsis, bowel preparation quality, and variations in observation angles can significantly affect lesion detection, thereby impacting the clinical applicability of the model. In future research, we will focus on real-time video analysis. Prior to formal clinical deployment, we intend to conduct simulation experiments using previously recorded colonoscopy videos. These videos are segmented into sequential image frames for analysis, enabling us to evaluate the temporal performance of the model, including the consistency of detection results across consecutive frames (temporal stability), the time delay between lesion appearance and its detection (detection latency), and the coherence of diagnostic decisions between adjacent frames (frame-to-frame consistency). Our team has accumulated substantial experience in detecting gastrointestinal lesions[10]. In subsequent studies, we plan to perform comprehensive clinical validations to further assess the effectiveness and practical utility of the system, ensuring that it aligns closely with real-world clinical requirements.

The results of this study preliminarily suggest that the AI system developed on the basis of YOLOv7 is valuable for improving the diagnosis of rNETs under white-light endoscopy while reducing misdiagnosis rates. The effectiveness of the proposed system in the detection of rNETs in real-world environments needs to be investigated in subsequent large-scale clinical trials.

Thanks Zi-Cheng Li for the valuable assistance during the revision of the manuscript.

| 1. | Vitale G, Rybinska I, Arrivi G, Marotta V, Di Iasi G, Filice A, Nardi C, Colao A, Faggiano A; NIKE Group. Cabozantinib in the Treatment of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Insights across Different Tumor Origins. Neuroendocrinology. 2025;115:460-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Maione F, Chini A, Milone M, Gennarelli N, Manigrasso M, Maione R, Cassese G, Pagano G, Tropeano FP, Luglio G, De Palma GD. Diagnosis and Management of Rectal Neuroendocrine Tumors (NETs). Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11:771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Osagiede O, Habermann E, Day C, Gabriel E, Merchea A, Lemini R, Jabbal IS, Colibaseanu DT. Factors associated with worse outcomes for colorectal neuroendocrine tumors in radical versus local resections. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020;11:836-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ramage JK, De Herder WW, Delle Fave G, Ferolla P, Ferone D, Ito T, Ruszniewski P, Sundin A, Weber W, Zheng-Pei Z, Taal B, Pascher A; Vienna Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Colorectal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103:139-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chablaney S, Zator ZA, Kumta NA. Diagnosis and Management of Rectal Neuroendocrine Tumors. Clin Endosc. 2017;50:530-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dąbkowski K, Szczepkowski M, Kos-Kudła B, Starzynska T. Endoscopic management of rectal neuroendocrine tumours. How to avoid a mistake and what to do when one is made? Endokrynol Pol. 2020;71:343-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dąbkowski K, Rusiniak-Rossińska N, Michalska K, Białek A, Urasińska E, Kos-Kudła B, Starzyńska T. Endoscopic treatment of rectal neuroendocrine tumors in a 13-year retrospective single-center study: are we following the guidelines? Pol Arch Intern Med. 2021;131:241-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shim KN, Yang SK, Myung SJ, Chang HS, Jung SA, Choe JW, Lee YJ, Byeon JS, Lee JH, Jung HY, Hong WS, Kim JH, Min YI, Kim JC, Kim JS. Atypical endoscopic features of rectal carcinoids. Endoscopy. 2004;36:313-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Park SB, Kim DJ, Kim HW, Choi CW, Kang DH, Kim SJ, Nam HS. Is endoscopic ultrasonography essential for endoscopic resection of small rectal neuroendocrine tumors? World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2037-2043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lin Y, Zhang X, Li F, Zhang R, Jiang H, Lai C, Yi L, Li Z, Wu W, Qiu L, Yang H, Guan Q, Wang Z, Deng L, Zhao Z, Lu W, Lun W, Dai J, He S, Bai Y. A deep neural network improves endoscopic detection of laterally spreading tumors. Surg Endosc. 2025;39:776-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nwoye CI, Padoy N. SurgiTrack: Fine-grained multi-class multi-tool tracking in surgical videos. Med Image Anal. 2025;101:103438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yin SM, Lien JJ, Chiu IM. Deep learning implementation for extrahepatic bile duct detection during indocyanine green fluorescence-guided laparoscopic cholecystectomy: pilot study. BJS Open. 2025;9:zraf013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Niikura R, Aoki T, Shichijo S, Yamada A, Kawahara T, Kato Y, Hirata Y, Hayakawa Y, Suzuki N, Ochi M, Hirasawa T, Tada T, Kawai T, Koike K. Artificial intelligence versus expert endoscopists for diagnosis of gastric cancer in patients who have undergone upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2022;54:780-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ikenoyama Y, Yoshio T, Tokura J, Naito S, Namikawa K, Tokai Y, Yoshimizu S, Horiuchi Y, Ishiyama A, Hirasawa T, Tsuchida T, Katayama N, Tada T, Fujisaki J. Artificial intelligence diagnostic system predicts multiple Lugol-voiding lesions in the esophagus and patients at high risk for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Endoscopy. 2021;53:1105-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang P, Berzin TM, Glissen Brown JR, Bharadwaj S, Becq A, Xiao X, Liu P, Li L, Song Y, Zhang D, Li Y, Xu G, Tu M, Liu X. Real-time automatic detection system increases colonoscopic polyp and adenoma detection rates: a prospective randomised controlled study. Gut. 2019;68:1813-1819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 591] [Article Influence: 84.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhou S, Xie Y, Feng X, Li Y, Shen L, Chen Y. Artificial intelligence in gastrointestinal cancer research: Image learning advances and applications. Cancer Lett. 2025;614:217555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Srirajaskanthan R, Clement D, Brown S, Howard MR, Ramage JK. Optimising Outcomes and Surveillance Strategies of Rectal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:2766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Abboud Y, Pendyala N, Le A, Mittal A, Alsakarneh S, Jaber F, Hajifathalian K. The Incidence of Rectal Neuroendocrine Tumors Is Increasing in Younger Adults in the US, 2001-2020. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:5286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cope J, Srirajaskanthan R. Rectal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Why Is There a Global Variation? Curr Oncol Rep. 2022;24:257-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ma XX, Wang LS, Wang LL, Long T, Xu ZL. Endoscopic treatment and management of rectal neuroendocrine tumors less than 10 mm in diameter. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;15:19-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | O'Neill S, Haji A, Ryan S, Clement D, Sarras K, Hayee B, Mulholland N, Ramage JK, Srirajaskanthan R. Nodal metastases in small rectal neuroendocrine tumours. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23:3173-3179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang Z, Yu G, Li L, Qi S, Liu Q. A retrospective analysis of 32 small and well-differentiated rectal neuroendocrine tumors with regional or distant metastasis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2023;115:336-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Delle Fave G, O'Toole D, Sundin A, Taal B, Ferolla P, Ramage JK, Ferone D, Ito T, Weber W, Zheng-Pei Z, De Herder WW, Pascher A, Ruszniewski P; Vienna Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Gastroduodenal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103:119-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 366] [Article Influence: 36.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Moon CM, Huh KC, Jung SA, Park DI, Kim WH, Jung HM, Koh SJ, Kim JO, Jung Y, Kim KO, Kim JW, Yang DH, Shin JE, Shin SJ, Kim ES, Joo YE. Long-Term Clinical Outcomes of Rectal Neuroendocrine Tumors According to the Pathologic Status After Initial Endoscopic Resection: A KASID Multicenter Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1276-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Frydman A, Srirajaskanthan R. An Update on the Management of Rectal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2024;25:1461-1470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Fine C, Roquin G, Terrebonne E, Lecomte T, Coriat R, Do Cao C, de Mestier L, Coffin E, Cadiot G, Nicolli P, Lepiliez V, Hautefeuille V, Ramos J, Girot P, Dominguez S, Céphise FV, Forestier J, Hervieu V, Pioche M, Walter T. Endoscopic management of 345 small rectal neuroendocrine tumours: A national study from the French group of endocrine tumours (GTE). United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:1102-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Gopakumar H, Jahagirdar V, Koyi J, Dahiya DS, Goyal H, Sharma NR, Perisetti A. Role of Advanced Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in the Comprehensive Management of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:4175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Misawa M, Kudo SE. Current Status of Artificial Intelligence Use in Colonoscopy. Digestion. 2025;106:138-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/