Published online Nov 28, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i44.112576

Revised: September 6, 2025

Accepted: October 20, 2025

Published online: November 28, 2025

Processing time: 120 Days and 13.9 Hours

Endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) is an effective treatment for gas

To identify risk factors for moderate to severe pain following EFTR and to construct a predictive nomogram for clinical use.

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients who underwent EFTR at our center between October 1, 2019, and June 1, 2025. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify risk factors associated with postoperative moderate to severe pain following EFTR. A nomogram was subsequently constructed based on a multivariate logistic regression model to predict the risk of moderate to severe pain following EFTR. The discrimination and calibration of the nomogram were evaluated by estimating the area under the receiver operator characteristic curve and by bootstrap resampling and visual inspection of the calibration curve. The clinical utility of the nomogram was assessed using decision curve analysis.

A total of 172 patients who underwent EFTR were included in the study, of whom 27 (15.7%) experienced moderate to severe postoperative pain. Based on multivariate logistic regression analysis, higher body mass index was significantly associated with a reduced risk of moderate to severe postoperative pain [odds ratio (OR) = 0.83, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.72-0.95, P = 0.0091], while a lesion size ≥ 3 cm (OR = 12.01, 95%CI: 3.03-47.68, P = 0.0004) and benign lesions (OR = 12.12, 95%CI: 2.70-54.49, P = 0.0011) were significantly associated with an increased risk. The nomogram demonstrated excellent discriminatory ability, with an area under the curve of 0.792 (95%CI: 0.690-0.894), a sensitivity of 63%, and a specificity of 84%. The calibration curve showed excellent agreement between predicted and observed probabilities (mean absolute error = 0.022). Subsequent decision curve analysis further confirmed the nomogram’s clinical utility.

In this study, we successfully developed a predictive nomogram for identifying the risk of moderate to severe pain following EFTR surgery.

Core Tip: Endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) is increasingly used for gastrointestinal lesion treatment but is often complicated by moderate to severe postoperative pain. This retrospective study identifies key risk factors, including body mass index, lesion size, and lesion nature, associated with postoperative pain after EFTR. A novel nomogram was developed to predict individual patient risk, demonstrating strong predictive accuracy and clinical utility. This tool may guide personalized pain management strategies, improving patient recovery and quality of life after EFTR.

- Citation: Sun GY, Gao TJ, Sun Y, Jia W, Yang Z. Risk factors with nomogram construction for moderate to severe pain after endoscopic full-thickness resection. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(44): 112576

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i44/112576.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i44.112576

Endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR), an emerging minimally invasive therapeutic technique, has been increasingly utilized for the resection of both benign and malignant lesions in the gastrointestinal tract[1]. EFTR combined with dedicated suturing devices can be used for the removal of select subepithelial and epithelial lesions that are not amenable to conventional endoscopic resection techniques[2]. Compared with conventional surgical procedures, EFTR offers significant advantages such as reduced trauma, faster recovery, and shorter hospital stays, making it increasingly favored by both clinicians and patients. However, in comparison to other endoscopic treatments like endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection, EFTR is associated with a higher incidence of postoperative pain[3,4]. Postoperative pain not only prolongs the length of hospital stay but may also serve as an early indicator of more serious complications[5].

Severe postoperative pain can significantly impair the recovery process and quality of life for patients. Currently, research on pain following EFTR is limited, with most studies focusing on postoperative analgesic strategies rather than systematically exploring the underlying mechanisms and risk factors of pain. In particular, the factors influencing postoperative pain after EFTR for upper gastrointestinal tract lesions remain insufficiently elucidated, and the lack of robust clinical evidence hampers the development of targeted pain prevention and management strategies. Identifying relevant risk factors is essential for early and accurate risk assessment, enabling the implementation of individualized analgesic protocols and optimization of perioperative care. Furthermore, this can significantly enhance postoperative comfort and accelerate the recovery process for patients[6,7].

Therefore, this study aims to retrospectively analyze patient demographics and perioperative factors to identify potential risk factors associated with moderate to severe postoperative pain following upper gastrointestinal EFTR. Additionally, a predictive nomogram will be developed and validated to estimate the risk of such pain, providing a practical tool for early risk assessment and individualized pain management.

Patients who underwent EFTR at our hospital between October 2019 and June 2025 were retrospectively included in this study. This retrospective study was approved by the hospital’s ethics review committee, with the approval No. Y (2025) 332. Given the retrospective nature of the study, patient information was collected from existing medical records without any direct intervention. All personal identifiers (such as names, identification numbers, or other identifiable information) were anonymized during data extraction to ensure patient confidentiality. Furthermore, all study findings will be presented in aggregate form or as final statistical results on public platforms, and original data will not be disclosed unless necessary. Therefore, the ethics committee granted a waiver of informed consent for this study.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Age between 18 and 80 years; (2) Presence of subepithelial or epithelial lesions deemed suitable for EFTR based on preoperative endoscopic ultrasound or computed tomography evaluation; (3) No significant cognitive impairment before surgery and the ability to self-report pain levels; and (4) Complete clinical data available.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Presence of moderate to severe pain or a history of chronic pain prior to surgery; (2) Use of analgesics for pain unrelated to the surgical site; and (3) Occurrence of major postoperative complications such as delayed perforation, bleeding requiring endoscopic intervention, or transfer to the intensive care unit within 24 hours postoperatively.

In this study, demographic characteristics, medical history, surgical details, and follow-up data for each patient were collected from clinical databases and medical records. Demographic data included age, sex, and body mass index (BMI). Documented medical history encompassed hypertension, diabetes, smoking and alcohol consumption status, previous surgical history, and history of prior endoscopic procedures. Regarding surgery-related variables, we collected infor

Moderate to severe pain was defined based on the administration of analgesic medication during this period. Ward nursing staff conducted pain assessments every 4 hours using the 4-point Verbal Rating Scale. If a patient reported moderate to severe pain on the 4-point Verbal Rating Scale, analgesics were administered, and the episode was recorded as an event of significant postoperative pain. The primary outcome of this study was the occurrence of moderate to severe pain within 48 hours following EFTR.

Additional endoscopic interventions referred to the performance of supplementary procedures such as endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic submucosal dissection, cold forceps polypectomy, or cold snare polypectomy. PONV was defined as the administration of antiemetic medication within 48 hours after surgery or documentation of PONV in the medical record. Postoperative fever was defined as a body temperature exceeding 38.5 °C after the procedure.

Statistical analysis was conducted with R software (version 4.3.2; http://www.Rproject.org) and SPSS 26.0 software package (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Quantitative variables are expressed as mean ± SD, with normality of distribution assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, normally distributed variables were subsequently compared using the independent sample t-test or analysis of variance, while non-normally distributed variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney test. Qualitative variables are expressed as frequency, and were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test. Based on the univariable analysis, variables with P < 0.05 were selected for entry into the multivariate logistic regression model and subsequently refined using a backward stepwise elimination approach.

We developed a nomogram for moderate to severe pain following EFTR. We further evaluated the performance of the nomogram in terms of discrimination and calibration. The discriminatory ability of the nomogram to distinguish between non-moderate/severe pain and moderate to severe pain was evaluated by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Additionally, we performed internal validation of the predictive performance using 1000 bootstrap resampling iterations and compared the predicted probabilities of moderate to severe pain with the observed outcomes among patients undergoing EFTR. Decision curve analysis was conducted to assess the clinical utility of the predictive scoring system.

Between October 2019 and June 2025, a total of 179 consecutive patients were screened in our Department of Endoscopy. After excluding 7 patients (2 with incomplete data, 3 who were referred for surgical resection, 1 who underwent palliative resection, and 1 who developed delayed perforation), a total of 172 patients were ultimately included in the analysis. The cohort comprised 106 men and 56 women with a mean age of 55.97 ± 11.69 years. Based on post-procedural pain severity, 135 patients (83.3%) reported no or mild pain, whereas 27 (16.7%) experienced moderate to severe pain. Baseline characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

| Variables | Severe postoperative pain | χ2/t | P value | |

| No (n = 145) | Yes (n = 27) | |||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18-39 | 11 (7.6) | 7 (25.9) | - | 0.118 |

| 40-49 | 19 (13.1) | 2 (7.4) | - | - |

| 50-59 | 45 (31.0) | 6 (22.2) | - | - |

| 60-69 | 55 (37.9) | 10 (37.0) | - | - |

| 70-79 | 15 (10.3) | 2 (7.4) | - | - |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 56 (38.6) | 10 (37.0) | < 0.001 | 1 |

| Female | 89 (61.4) | 17 (62.0) | - | - |

| Smoking (years) | ||||

| No | 105 (72.4) | 21 (77.8) | 0.117 | 0.733 |

| Yes | 40 (27.6) | 6 (22.2) | - | - |

| Drinking | ||||

| No | 109 (64.6) | 23 (69.8) | 0.779 | 0.377 |

| Yes | 36 (32.0) | 4 (23.9) | - | - |

| History of surgery | ||||

| No | 79 (54.5) | 16 (59.2) | 0.061 | 0.805 |

| Yes | 66 (45.5) | 11 (40.7) | - | - |

| History of endoscopic surgical | ||||

| No | 99 (68.2) | 18 (66.7) | < 0.001 | 1 |

| Yes | 46 (31.7) | 9 (33.3) | - | - |

| History of diabetes | ||||

| No | 127 (87.6) | 22 (81.5) | - | 0.368 |

| Yes | 18 (12.4) | 5 (18.5) | - | - |

| History of hypertension | ||||

| No | 92 (63.5) | 20 (74.1) | 0.712 | 0.399 |

| Yes | 53 (36.6) | 7 (25.9) | - | - |

| Additional endoscopic therapy | ||||

| No | 99 (68.2) | 21 (77.8) | 0.576 | 0.448 |

| Yes | 46 (31.7) | 6 (22.2) | - | - |

| Lesion size | ||||

| < 1 | 65 (44.8) | 6 (22.2) | - | 0.003 |

| 1 ≤ x < 2 | 47 (32.4) | 9 (33.3) | - | - |

| 2 ≤ x < 3 | 22 (15.2) | 3 (11.11) | - | - |

| ≥ 3 | 11 (7.6) | 9 (33.3) | - | - |

| Gastric body | 61 (42.1) | 18 (66.7) | - | 0.101 |

| Gastric fundus | 61 (42.1) | 5 (18.5) | - | - |

| Gastric antrum | 6 (4.1) | 2 (7.4) | - | - |

| Antrum-body junction | 5 (3.5) | 1 (3.7) | - | - |

| Cardia | 6 (4.1) | 0 (0) | - | - |

| Duodenum | 6 (4.1) | 1 (3.7) | - | - |

| PONV | ||||

| No | 137 (94.5) | 24 (88.9) | - | 0.382 |

| Yes | 8 (5.5) | 3 (11.1) | - | - |

| Preoperative K+ | ||||

| No | 132 (91.0) | 23 (85.2) | - | 0.312 |

| Yes | 13 (8.9) | 4 (14.8) | - | - |

| Fever | ||||

| No | 128 (88.3) | 23 (85.2) | - | 0.748 |

| Yes | 17 (11.7) | 4 (14.8) | - | - |

| Catheterization | ||||

| No | 131 (90.3) | 26(96.3) | - | 0.471 |

| Yes | 14 (9.7) | 1 (3.7) | - | - |

| Abdominal wall puncture | ||||

| No | 132 (91.0) | 23 (85.2) | - | 0.312 |

| Yes | 13 (8.9) | 4 (14.8) | - | - |

| Closure technique | ||||

| Hemostatic clip | 115 (79.3) | 15 (55.6) | 5.732 | 0.017 |

| Purse-string suture | 30 (20.7) | 12 (44.4) | - | - |

| Histological type | ||||

| Mesenchymal tumors | 130 (89.7) | 18 (66.7) | - | 0.003 |

| Neurogenic tumors | 7 (4.8) | 4 (14.8) | - | - |

| Dysplasia | 4 (2.8) | 0 (0) | - | - |

| Benign lesion | 4 (2.8) | 5 (18.5) | - | - |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 23.8 (IQR 4.79) | 22.6 (IQR 3.09) | - | 0.028 |

| Duration of surgery (minute), mean ± SD | 44 (IQR 32) | 73 (IQR 84) | - | 0.002 |

Univariate analysis identified lesion size (P = 0.003), closure technique (P = 0.017), histological type (P = 0.003), BMI (P = 0.028), and duration of surgery (P = 0.002) as potential risk factors (Table 1), which were subsequently included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. The stepwise regression analysis identified the following as independent risk factors for moderate to severe postoperative pain after upper gastrointestinal EFTR: BMI [odds ratio (OR) = 0.83, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.72-0.95, P = 0.0091], lesion size ≥ 3 cm (OR = 12.01, 95%CI: 3.03-47.68, P = 0.0004), and Benign lesion (OR = 12.12, 95%CI: 2.70-54.49, P = 0.0011) (Table 2).

| Variable | OR | Lower 95%CI | Upper 95%CI | P value |

| (Intercept) | 5.521 | 0.212 | 144.005 | 0.3045 |

| BMI | 0.828 | 0.719 | 0.954 | 0.0091 |

| Lesion size 1 | 2.072 | 0.643 | 6.68 | 0.2226 |

| Lesion size 2 | 1.351 | 0.262 | 6.953 | 0.7191 |

| Lesion size 3 | 12.01 | 3.025 | 47.684 | 0.0004 |

| Histological type 1 | 3.306 | 0.68 | 16.083 | 0.1384 |

| Histological type 2 | 0 | 0 | Inf | 0.9902 |

| Histological type 3 | 12.121 | 2.696 | 54.488 | 0.0011 |

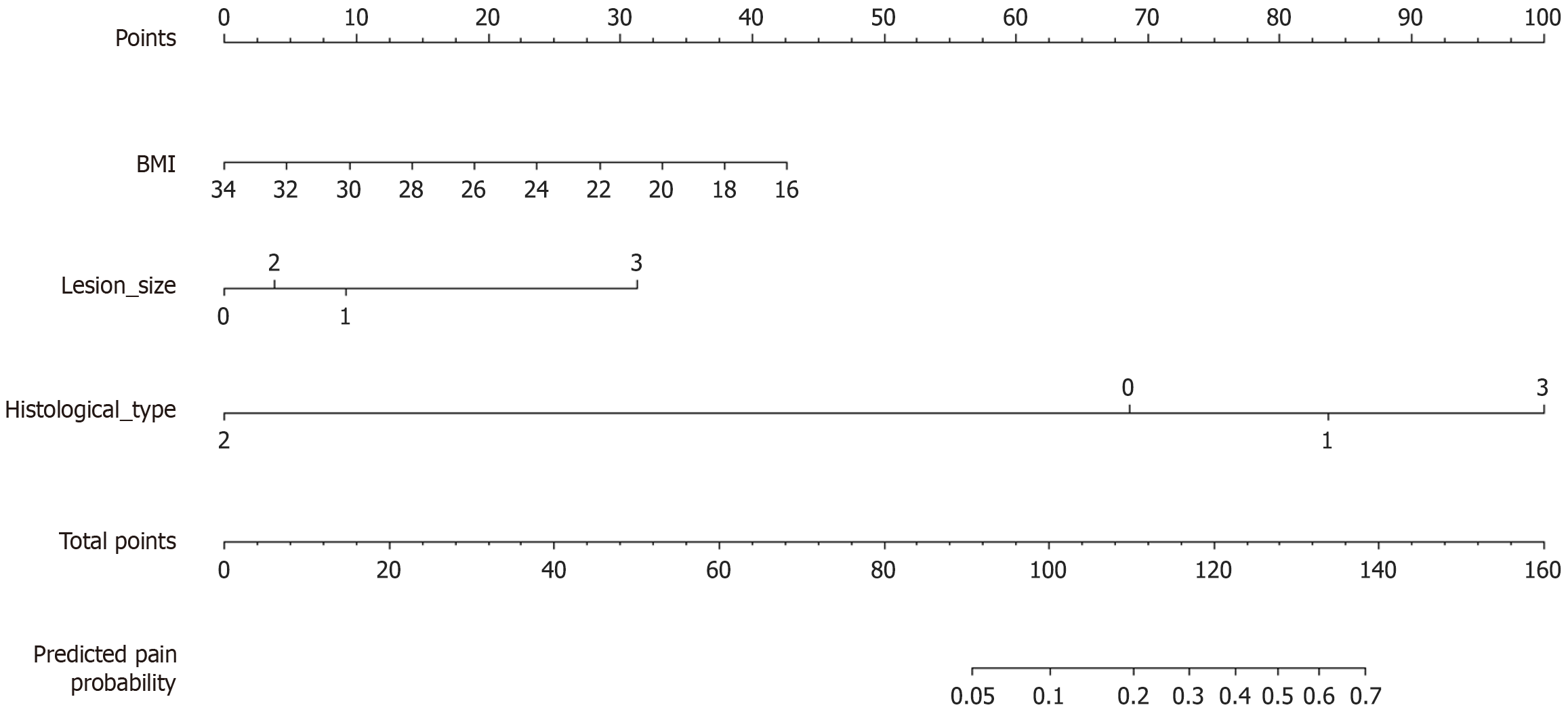

Based on the results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis, a nomogram was constructed to predict the risk of moderate to severe postoperative pain (Figure 1). In this nomogram, we used patients’ BMI as a continuous variable. Each value of the variables corresponds to a specific score, and the scores for the three variables included in the model are summed to calculate an individual’s total score. This total score is then mapped onto a point scale to estimate the probability of moderate to severe post-procedural complications for each patient.

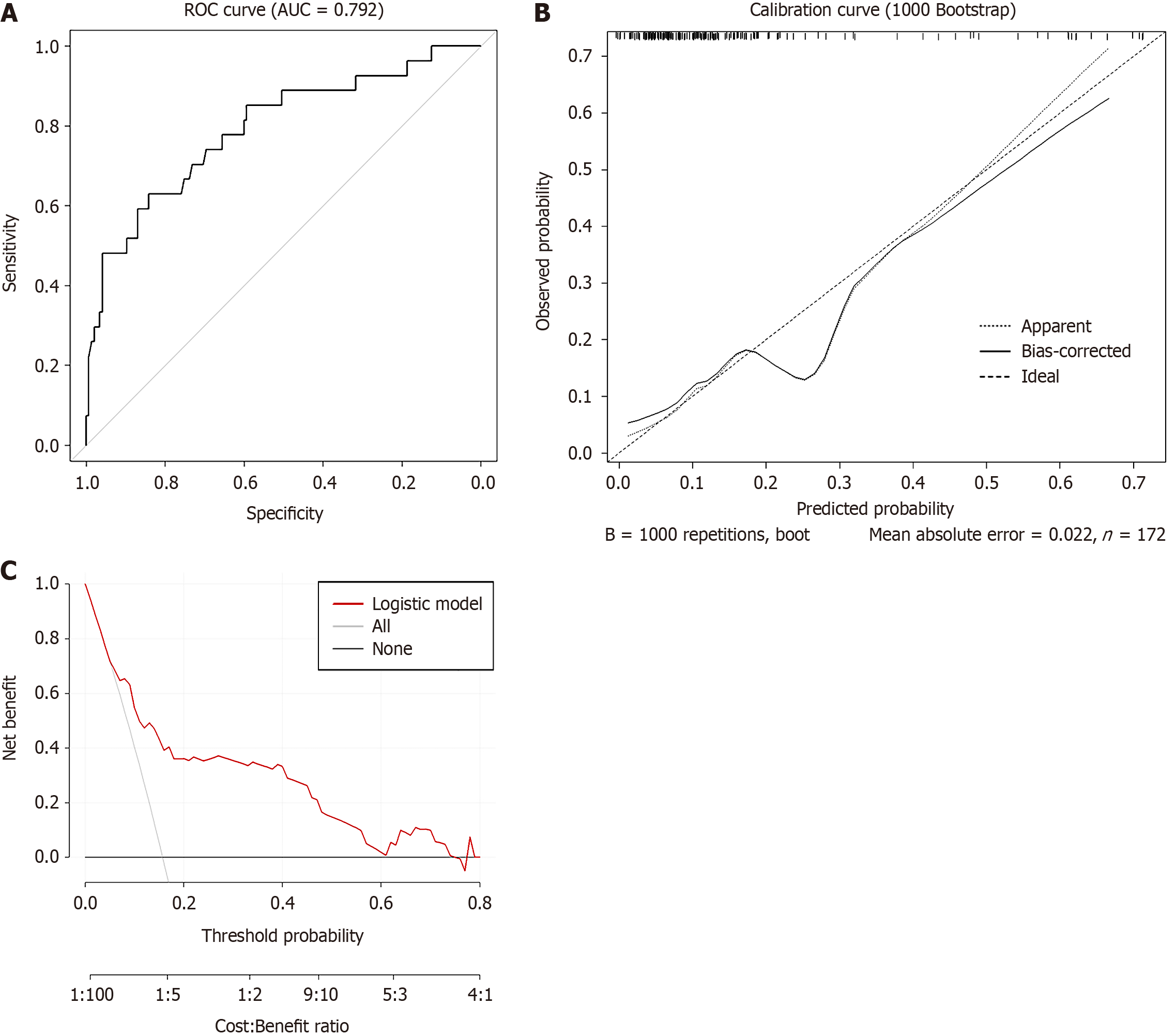

The nomogram demonstrated excellent discriminatory ability, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.792 (95%CI: 0.690-0.894, Figure 2A), a sensitivity of 63%, and a specificity of 84%. After 1000 bootstrap resamples for internal validation, the corrected AUC was 0.747, which remains within an acceptable range. The calibration curve showed a high degree of agreement between the predicted probabilities and the observed incidence of moderate to severe pain (Figure 2B). Decision curve analysis demonstrated that the nomogram provided a positive net benefit across a wide range of threshold probabilities, supporting its promising clinical utility (Figure 2C).

Our study identified lower BMI, larger lesions (≥ 3 cm), and benign pathology as independent predictors of moderate to severe pain after EFTR, and developed a predictive nomogram with good internal validation performance. Existing models in therapeutic endoscopy mainly focus on adverse events such as bleeding or perforation, rather than pain outcomes. To our knowledge, no prior studies have established a risk prediction tool specifically for postoperative pain in EFTR. Therefore, our nomogram addresses an important clinical gap. Our model incorporates easily accessible perioperative variables (BMI, lesion size, and pathology type), which makes it simple to apply in daily clinical practice.

Among the 172 patients included in this study, 27 cases (15.7%) experienced moderate to severe pain following EFTR. Our study revealed a counterintuitive finding: Higher BMI was significantly associated with a reduced risk of postoperative pain. We fully acknowledge the unexpected nature of this observation. Some studies have shown a positive correlation between BMI and the incidence of chronic pain[8,9]. Obesity contributes to pain perception through a dual mechanism: It increases susceptibility to chronic pain via inflammatory pathways while simultaneously elevating the threshold for acute pain through neuroadaptive analgesic mechanisms. Together, these processes interact across different time scales and stimulus types, shaping a complex pain phenotype. On one hand, adipose tissue secretes pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, which can induce a state of low-grade systemic inflammation. This, in turn, sensitizes nociceptive pathways and increases the risk of chronic pain[10,11]. On the other hand, research by Cifani et al[12] demonstrated that rats fed a high-fat diet exhibited significantly elevated pain thresholds compared to those on a standard diet[12,13]. This increase in pain tolerance was accompanied by upregulated expression of opioid and cannabinoid receptors in the brain, suggesting that the reduced pain sensitivity observed in obese individuals may result from the combined effects of the opioid and endocannabinoid systems. Studies have shown that obese individuals exhibit higher pain and non-painful heat stimulation thresholds, as well as lower subjective intensity ratings, specifically in abdominal areas rich in subcutaneous fat[14]. Overall, obese individuals tend to exhibit higher pain thresholds[15]. However, it should be noted that these mechanisms, largely derived from chronic or experimental pain models, may not fully apply to the context of acute postoperative pain and thus require further investigation.

Although EFTR is a minimally invasive procedure, managing larger lesions often involves serosal traction, muscular layer incision, and tissue dissection, which can provoke local postoperative inflammation and nerve irritation, thereby increasing pain. Additionally, inadvertent perforation during surgery may cause pneumoperitoneum, and closure with titanium clips can also exert traction on surrounding tissues, leading to referred pain. Even when closure is successful, leakage of gastric acid or bacteria may trigger localized peritonitis, resulting in persistent abdominal pain[16]. Furthermore, larger lesions generally indicate a more challenging resection, often accompanied by prolonged operative time and an increased risk of intraoperative bleeding[17]. In summary, lesions measuring ≥ 3 cm represent a significant risk factor for moderate to severe pain following EFTR. Therefore, thorough preoperative assessment of pain risk is essential, and more proactive postoperative analgesic management strategies should be implemented accordingly.

Interestingly, benign lesions were associated with a higher risk of moderate-to-severe pain after EFTR. Among patients with benign lesions who experienced postoperative pain, there were five cases, predominantly consisting of four with heterotopic pancreas and one with a cystic lesion accompanied by inflammation. In contrast, the four patients without postoperative pain all had purely inflammatory or hyperplastic lesions, including two cases of chronic mucosal inflammation, one epithelial cyst, and one polyp. Heterotopic pancreas types I-III contain functional pancreatic acini and ductal structures. Impaired drainage and obstruction of these ducts can lead to pancreatitis and pseudocyst formation[18]. Heterotopic pancreatic exocrine activity may represent one potential explanation, but other mechanisms should also be considered. Given the limited data, this finding should be viewed as a hypothesis-generating observation that requires further investigation.

This study has several inherent limitations: (1) Its retrospective design may affect the completeness and reliability of the data; (2) As a single-center study with a limited sample size, our work has certain restrictions in terms of generalizability. In addition, most EFTR procedures in this cohort were performed by highly experienced endoscopists with well-established technical expertise, and the largest lesion resected measured approximately 7 cm. While this reflects the maturity of EFTR practice at our center, it may also limit the applicability of our findings to other settings. Future multi-center collaborative studies are warranted to further validate and extend these results; and (3) Pain assessment relied on patients’ subjective reports and records of analgesic use, which may introduce some degree of evaluation bias. Therefore, future prospective studies with larger sample sizes and multi-center participation, along with active external validation, are needed to further confirm the robustness and generalizability of our findings.

This study identified lower BMI, lesion diameter ≥ 3 cm, and benign pathology as independent risk factors for moderate to severe pain following EFTR. Based on these findings, we developed a nomogram that effectively predicts the risk of moderate to severe postoperative pain. Early identification of high-risk patients and implementation of targeted interventions may significantly reduce risk of pain and improve the quality of postoperative recovery.

| 1. | Abdallah M, Suryawanshi G, McDonald N, Chandan S, Umar S, Azeem N, Bilal M. Endoscopic full-thickness resection for upper gastrointestinal tract lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:3293-3305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Guo JT, Zhang JJ, Wu YF, Liao Y, Wang YD, Zhang BZ, Wang S, Sun SY. Endoscopic full-thickness resection using an over-the-scope device: A prospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:725-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shanshan W, Shuren W, Zongwang Z. Painkiller administration after endoscopic submucosal dissection surgery: a retrospective real-world study. Ann Med. 2025;57:2499698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Luo X, An LX, Chen PS, Chang XL, Li Y. Efficacy of dexmedetomidine on postoperative pain in patients undergoing gastric and esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection: a study protocol for a randomized controlled prospective trial. Trials. 2022;23:491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Desomer L, Tate DJ, Pillay L, Awadie H, Sidhu M, Ahlenstiel G, Bourke MJ. Intravenous paracetamol for persistent pain after endoscopic mucosal resection discriminates patients at risk of adverse events and those who can be safely discharged. Endoscopy. 2023;55:611-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Maselli R, Massimi D, Ferrari C, Mondovì AN, Hassan C, Repici A. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) in advanced therapeutic flexible endoscopy: Introducing the concept of enhanced recovery after therapeutic endoscopy (ERATE). Dig Liver Dis. 2024;56:1253-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li J, Kang G, Liu T, Liu Z, Guo T. Feasibility of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocols Implemented Perioperatively in Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastric Cancer: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2023;33:74-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Stone AA, Broderick JE. Obesity and pain are associated in the United States. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20:1491-1495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stokes AC, Xie W, Lundberg DJ, Hempstead K, Zajacova A, Zimmer Z, Glei DA, Meara E, Preston SH. Increases in BMI and chronic pain for US adults in midlife, 1992 to 2016. SSM Popul Health. 2020;12:100644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Watkins LR, Maier SF, Goehler LE. Immune activation: the role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in inflammation, illness responses and pathological pain states. Pain. 1995;63:289-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 484] [Cited by in RCA: 476] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sommer C, Kress M. Recent findings on how proinflammatory cytokines cause pain: peripheral mechanisms in inflammatory and neuropathic hyperalgesia. Neurosci Lett. 2004;361:184-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 588] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cifani C, Avagliano C, Micioni Di Bonaventura E, Giusepponi ME, De Caro C, Cristiano C, La Rana G, Botticelli L, Romano A, Calignano A, Gaetani S, Micioni Di Bonaventura MV, Russo R. Modulation of Pain Sensitivity by Chronic Consumption of Highly Palatable Food Followed by Abstinence: Emerging Role of Fatty Acid Amide Hydrolase. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nealon CM, Patel C, Worley BL, Henderson-Redmond AN, Morgan DJ, Czyzyk TA. Alterations in nociception and morphine antinociception in mice fed a high-fat diet. Brain Res Bull. 2018;138:64-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Price RC, Asenjo JF, Christou NV, Backman SB, Schweinhardt P. The role of excess subcutaneous fat in pain and sensory sensitivity in obesity. Eur J Pain. 2013;17:1316-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Torensma B, Thomassen I, van Velzen M, In 't Veld BA. Pain Experience and Perception in the Obese Subject Systematic Review (Revised Version). Obes Surg. 2016;26:631-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cheng BQ, Du C, Li HK, Chai NL, Linghu EQ. Endoscopic resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Dig Dis. 2024;25:550-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang YP, Xu H, Shen JX, Liu WM, Chu Y, Duan BS, Lian JJ, Zhang HB, Zhang L, Xu MD, Cao J. Predictors of difficult endoscopic resection of submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer at the esophagogastric junction. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;14:918-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | LeCompte MT, Mason B, Robbins KJ, Yano M, Chatterjee D, Fields RC, Strasberg SM, Hawkins WG. Clinical classification of symptomatic heterotopic pancreas of the stomach and duodenum: A case series and systematic literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:1455-1478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/