Published online Nov 28, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i44.112524

Revised: September 13, 2025

Accepted: October 20, 2025

Published online: November 28, 2025

Processing time: 121 Days and 18.3 Hours

Although the relationship between somatic DNA polymerase epsilon (POLE) exonuclease domain mutations (EDMs) and colorectal cancer (CRC) is well established, the role of POLE non-EDMs in CRC remains unclear.

To identify POLE non-EDMs and EDMs in CRC, and to determine their associations with accompanying mutations and microsatellite instability (MSI).

In this retrospective study, next-generation sequencing was performed using a targeted colon cancer panel (Qiagen, DHS-003Z) on 356 CRC patients. Of these, 191 patients were found to carry POLE mutations. For these patients, MSI status was assessed using both real-time PCR (EasyPGX® Ready MSI kit) and immunohistochemistry, and accompanying somatic mutations were investigated.

POLE mutations were identified in 53.65% of the CRC patients. Among the POLE-mutant patients, 87.96% were classified as pMMR (MSI-L), and 12.04% as dMMR (MSI-H). The most frequently observed POLE non-EDM variant was exon 34 c.4337_4338delTG p.V1446fs*3. The POLE EDMs were present in exon 14, with two specific variants p.Y458F (0.52%) and p.Y468N (0.52%). The most common pathogenic variants accompanying the POLE mutations were in MLH3, MSH3, KRAS, PIK3CA, and BRAF genes. POLE mutations were associated with a high mutational burden and MSI in CRC, particularly in the dMMR phenotype. This association suggests that POLE mutations may serve as important biomarkers for understanding the genetic profile of the disease and may be used in the clinical management of CRC.

POLE mutations, especially non-EDMs, are frequent in MSI-L CRC and often co-occur with MLH3, MSH3, KRAS, PIK3CA, and BRAF, highlighting their potential role in tumor biology and as biomarkers for personalized treatment. Functional validation and multicenter studies are needed.

Core Tip: This study highlights the overlooked role of DNA polymerase epsilon (POLE) non-exonuclease domain mutations in colorectal cancer. By integrating next-generation sequencing with microsatellite instability testing, we show that POLE mutations are frequent, particularly in microsatellite-low tumors, and are often accompanied by co-mutations in MLH3, MSH3, KRAS, PIK3CA, and BRAF. These findings extend beyond the classical exonuclease domain hotspots, suggesting that both exonuclease and non-exonuclease POLE variants may serve as valuable biomarkers for prognosis and support the development of personalized treatment strategies in colorectal cancer management.

- Citation: Taskiran I, Orenay-Boyacioglu S, Boyacioglu O, Erdogdu IH, Culhaci N, Meteoglu I. DNA polymerase epsilon-mutant colorectal cancers: Insights into non-exonuclease domain mutation variants, microsatellite instability status, and co-mutation profiles. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(44): 112524

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i44/112524.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i44.112524

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most prevalent cancers worldwide. The genetic structure of CRCs is quite heterogeneous and exhibits different mutation profiles[1]. Within this diversity, mutations occurring in the DNA polymerase epsilon (POLE) gene constitute an important subgroup[2]. The POLE gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 12 (12q24.33) in the human genome and spans approximately 100 kb. It comprises 49 exons and encodes the catalytic subunit of the POLE (Pol ε) complex, which is involved in replicative DNA synthesis[1]. POLE is highly expressed in tissues with elevated cell proliferation, particularly during the S phase of the cell cycle. This expression pattern underscores its critical role in DNA replication and repair processes[3]. The protein encoded by this gene consists of two major functional domains: A C-terminal 3′→5′ exonuclease domain (EDM) and an N-terminal DNA polymerase domain (non-EDM)[4]. Mutations in the POLE gene are predominantly clustered within the EDM, spanning exons 9 to 14. These mutations are associated with a hypermutated phenotype and enhanced responsiveness to immune checkpoint inhibitors[4,5]. Notably, hotspot variants such as P286R, V411 L, and S459F impair the proofreading function of the polymerase, leading to an increased mutational burden, and may contribute to the development of microsatellite-stable (MSS) tumors that are classified as microsatellite instability (MSI) negative subtypes. This conditions may affect the immunotherapy response of POLE-mutant CRC patients[5-7]. Non-EDM variants may also contribute to tumor development by disrupting the structural integrity and replication fidelity of DNA polymerase ε. Moreover, previous studies have reported non-EDMs in different tumor types (e.g., endometrial and CRC)[8,9] but their biological and clinical significance remains less well elucidated compared to EDMs, indicating the need for further investigations.

In POLE-mutant CRC, various co-mutations are also frequently observed in other genes. These co-mutations may affect the behavior of tumors and their responses to treatment[10]. For example, mutations are frequently observed in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes such as TP53, KRAS, and PIK3CA. TP53 mutations may accelerate tumor development by disrupting cell cycle control. KRAS mutations may affect the signaling pathways involved in cellular proliferation and differentiation[11-13].

In summary, while POLE EDM mutations are well characterized and associated with a high mutational burden and response to immune checkpoint inhibitors, the biological and clinical significance of non-EDM variants has been studied more limitedly. These variants, however, may influence tumor biology through potential effects on DNA replication and interactions with other co-mutations. Therefore, investigating non-EDMs in the Turkish CRC cohort provides important and pioneering insights by revealing population-specific mutational patterns that could contribute to personalized treatment strategies. Accordingly, this study aims to comprehensively evaluate both EDM and non-EDM POLE mutations in the Turkish CRC cohort, along with their MSI status and associated mutational patterns. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine these relationships in this population, highlighting the potential clinical significance of POLE non-EDMs, a relatively underexplored mutation group in CRC.

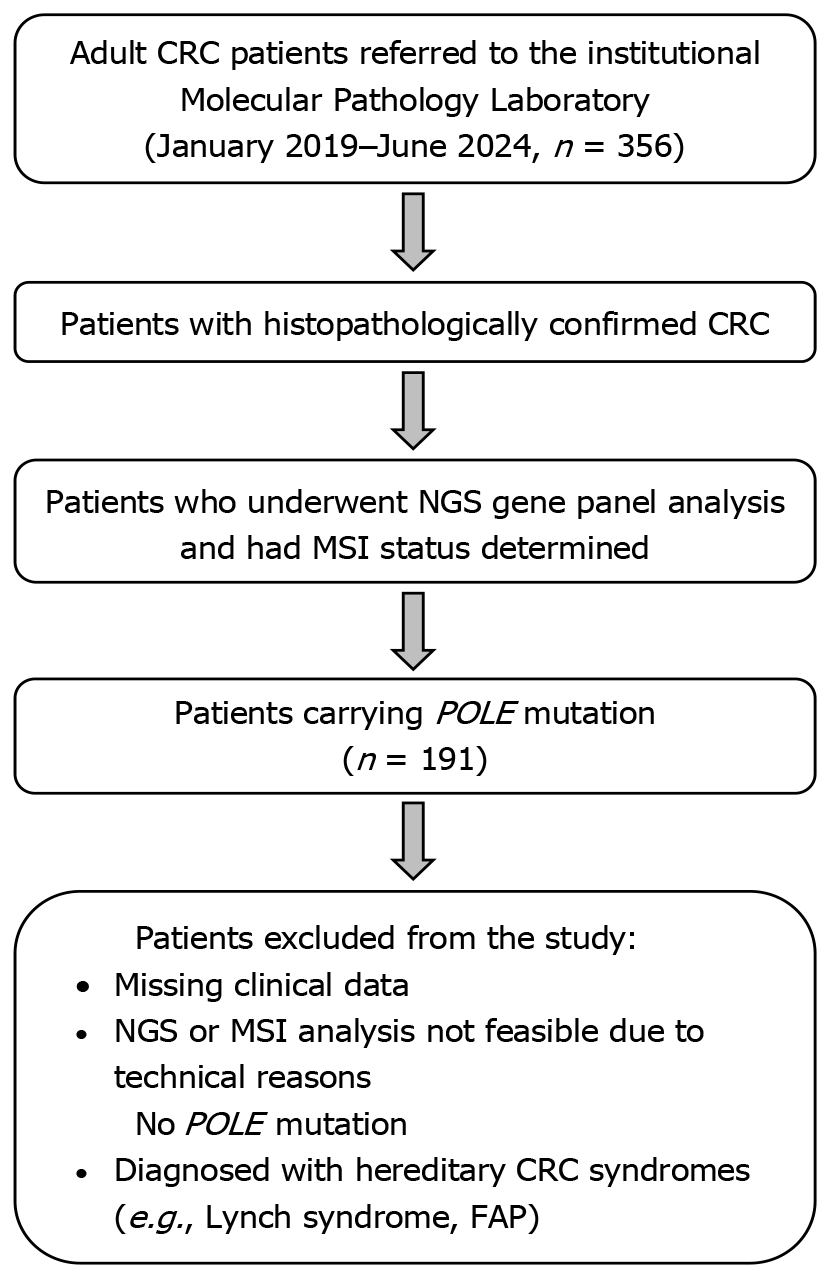

Between January 2019 and June 2024, the records of all adult patients (aged 18 and above) referred to our institutional Molecular Pathology Laboratory were retrospectively reviewed. Of the 356 consecutive patients who were diagnosed with CRC during colonoscopies performed in the gastroenterology clinic, confirmed by histopathological evaluation, underwent next-generation sequencing (NGS) gene mutation panel analysis, and had their MSI status determined, a total of 191 POLE-mutant CRC patients were included in the study. Although a documented family history of CRC was not available for all patients, none of the selected 191 POLE-mutant CRC cases exhibited clinical or genetic criteria indicative of hereditary CRC syndromes (e.g., Lynch syndrome or familial adenomatous polyposis). This indicates that the selected patient cohort in our study predominantly consisted of sporadic CRC cases. Patients with missing clinical data, those for whom NGS and MSI analyses could not be performed due to technical reasons, those without POLE mutations, and those diagnosed with hereditary CRC syndromes were excluded from the study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the patients enrolled in the study are summarized in Figure 1.

This study was approved by the Institutional Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee (2024/#138), and the criteria of the Declaration of Helsinki were observed.

DNA was isolated from paraffin-embedded tissue sections (10 µm in thickness) of the patients using the Qiagen GeneReader FFPE DNA isolation kit, following the kit's protocol, and conducted on the QIAcube (Qiagen Hilden, Germany) automated isolation device. Quantification and purity of the isolated DNA samples were conducted on a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies, CA, United States).

In this study, the MSI status of the patients was evaluated using both real-time PCR and immunohistochemistry (IHC), as previously described[14].

Real-time PCR was employed to detect MSI status using the EasyPGX® Ready MSI kit, which compares the microsatellite regions in tumor tissues with those in normal tissues. This kit was used to evaluate five microsatellite loci: BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-24, and MONO-27. Primer sequences are proprietary per the manufacturer’s protocol and were not disclosed. Instability at one microsatellite locus was classified as low MSI (MSI-L), instability at two or more loci as high MSI (MSI-H), and stability at all five loci as stable MS (MSS).

The expression of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 proteins was analyzed by IHC. FFPE tissue sections were cleared with xylene, dehydrated using an alcohol series, and processed with DAKO solution at 97 °C. The sections were then incubated with the appropriate antibodies for MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, and MSH6. Analyses were performed on an Autostainer Link 48 device and antigen-antibody interactions were evaluated using diaminobenzidine. Loss of nuclear staining was checked in both internal control and tumor tissues; deficient MMR proteins (dMMR) (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) were accepted as MSI-H, and the presence of all proteins was accepted as a proficient MMR (pMMR).

This dual approach aligns with established guidelines and ensures accurate MSI classification.

Between 100 and 250 ng of DNA was utilized for library construction using the QIAseq Targeted DNA Human CRC Panel (#DHS-002Z, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), which encompasses 71 genes commonly mutated in CRC. Each DNA fragment was tagged with a 12-base unique molecular index (UMI) to ensure accurate read identification. Library sequencing was carried out on the Illumina MiniSeq system (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, United States) employing a 2 × 150 bp paired-end format. According to the kit configuration, the MiniSeq platform yields approximately 7.5-8 million reads in mid-output mode and up to 25 million reads in high-output mode. In the present study, sequencing parameters were adjusted to obtain an average on-target coverage depth of ≥ 250 × for tumor samples, with each case achieving a minimum overall coverage of 30 ×. Raw reads were subsequently aligned to the GRCh37 (hg19) human reference genome.

Variant detection, annotation, scoring, and filtering were conducted using the QIAseq Targeted Panel Analysis plug-in designed specifically for this panel and operated via the Biomedical Genomics Workbench v5 software (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, United States). To enhance variant reliability, a stepwise filtering pipeline was applied: Confidence filter: Variants commonly found in public reference databases (Allele Frequency Community, 1000 Genomes Project, ExAC, NHLBI ESP) were excluded. Quality filter: Variants with a call quality below 20 or with a population frequency greater than 0.5% were removed. Genetic filter: Only pathogenic/potentially pathogenic and loss-of-function alterations (e.g., frameshift, nonsense) were retained, and the UMI-based variant allele frequency (VAF) was restricted to the 1%-45% range. For downstream interpretation of somatic mutations, the R/Bioconductor package maftools was employed, while mutation distribution patterns were visualized using the ggplot2 Library. Variants were divided into four categories according to cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment effects.

Analysis of the data was performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). χ2 test was utilized for comparing the categorical data. The significance level was set at P < 0.05. The results are presented as numbers and percentages.

A POLE mutation was observed in 191 (53.65%) of 356 CRC patients. All clinical and pathological features of POLE-mutant CRC patients are presented in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Value |

| Gendera | |

| Female | 69 (36.13) |

| Male | 122 (63.87) |

| Age at diagnosis, years | mean ± SD |

| Female | 63.6 ± 12.3 |

| Male | 66.6 ± 10.2 |

| All POLE-mutant CRC patients | 65.5 ± 11.1 |

| Differentiation degreea | |

| Well differentiated | 80 (41.88) |

| Moderately differentiated | 73 (38.22) |

| Poorly differentiated | 38 (19.90) |

| Localizationa | |

| Colon | 160 (83.77) |

| Rectum | 31 (16.23) |

The most frequently observed variation in the POLE gene in patients was the non-EDM variant exon 34 c.4337_4338delTG p.V1446fs*3 (conflicting classifications of pathogenicity), identified in 182 patients (95.29%) (Table 2). Other observed POLE non-EDM variants in the patients included p.D612N (0.52%), p.R1909 (0.52%), p.N518fs*10 (0.52%), p.Q1774* (0.52%), p.Q911* (0.52%), p.A1885T (0.52%), and p.L1171fs*6 (0.52%). POLE EDM (exons 9-14) mutations were rare, and only p.Y458F (0.52%) and p.Y468N (0.52%) variants located in exon 14 were detected in patients (Table 2).

| POLE mutation | Exon | Nucleotide substitution | Protein change | Mutation type | Clinical significance |

| Non-EDM | 34 | c.4337_4338delTG | p.V1446fs*3 | Microsatellite (frameshift) | Conflicting classifications of pathogenicity |

| EDM | 14 | c.1373A>T | p.Y458F | Nonsense | Pathogenic |

| EDM | 14 | c.1402T>A | p.Y468N | Missense | Uncertain significance |

| Non-EDM | 17 | c.1834G>A | p.D612N | Missense | Uncertain significance |

| Non-EDM | 42 | c.5725C>T | p.R1909 | Nonsense | Pathogenic |

| Non-EDM | 15 | c.1551delC | p.N518fs*10 | Deletion | Pathogenic |

| Non-EDM | 41 | c.5653G>A | p.A1885T | Frameshift | Uncertain significance |

| Non-EDM | 29 | c.3510dupA | p.L1171fs*6 | Duplication | Pathogenic |

| Non-EDM | 39 | c.5320C>T | p.Q1774* | Nonsense | Pathogenic |

| Non-EDM | 24 | c.2731C>T | p.Q911* | Nonsense | Pathogenic |

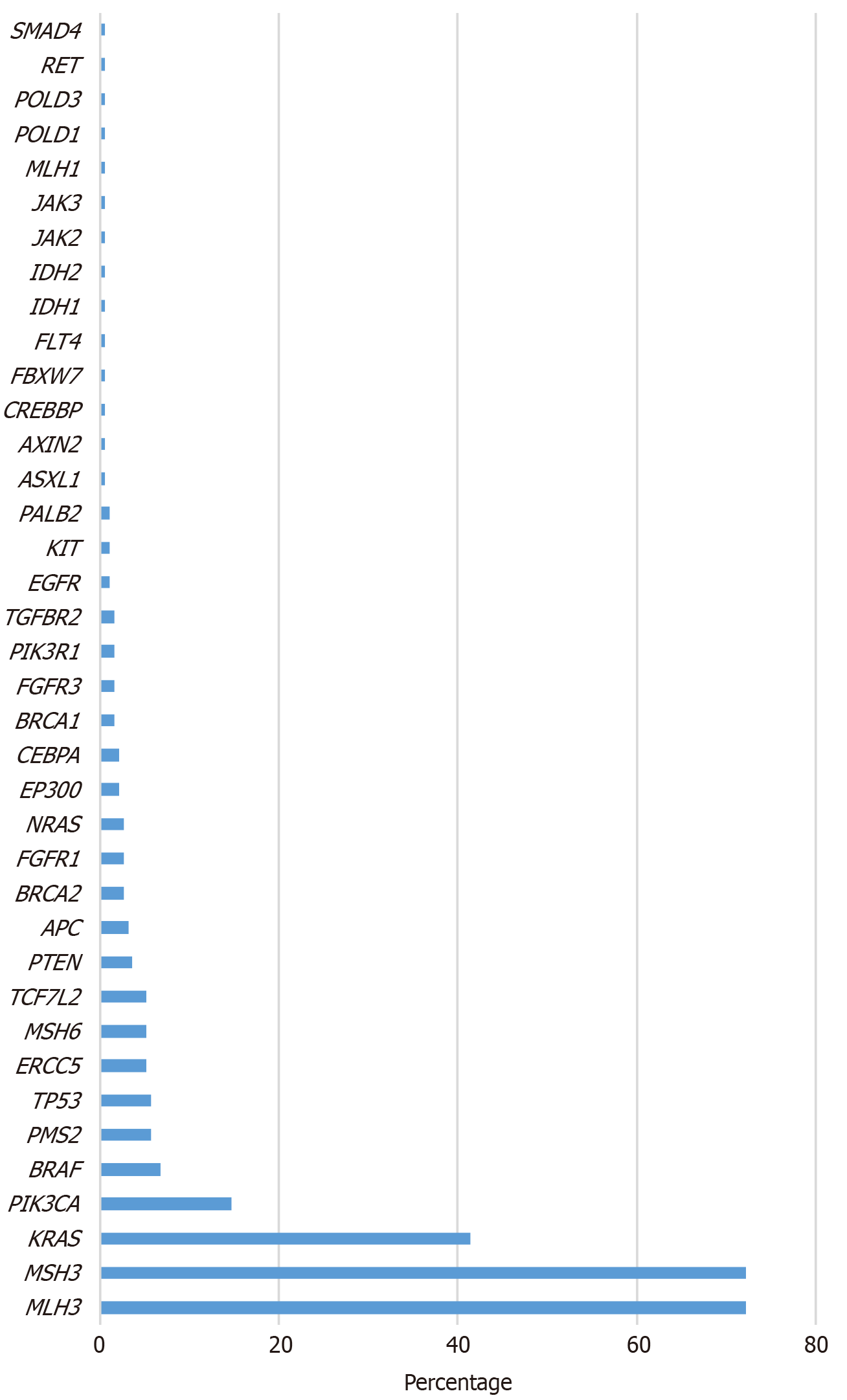

The most frequent mutations accompanying POLE mutations were in the MLH3 (72.25% in non-EDM, 100% in EDM) and MSH3 (72.25% in non-EDM, 50% in EDM) genes, followed by KRAS (41.36%), PIK3CA (14.66%), BRAF (6.81%), PMS2 (5.76%), TP53 (5.76%), MSH6 (5.24%), ERCC5 (5.24%), and TCF7 L2 (5.24%) in non-EDM cases (Figure 2). All gene variations accompanying POLE mutations in the cohort are presented in Table 3.

| POLE mutations | Gene | Nucleotide substitution | Protein change |

| APC | c.994C>T, c.646C>T, c.4348C>T, c.1690C>T, c.4192_4193delAG, c.4729G>T | p.R332*, p.R216*, p.R1450*, p.R564*, p.R1399fs*9, p.E1577* | |

| ASXL1 | c.1188_1201delGCGTGGTGGT | p.Q396fs*9 | |

| AXIN2 | c.1195C>T | p.R399* | |

| BAX | c.763A>T, c.121dupG | p.I255F, p.E41fs*33 | |

| BLM | c.1544delA | p.N515fs*16 | |

| BRAF | c.1742A>T, c.2141T>A, c.1799T>A, c.2102G>T, c.1406G>C, c.1790T>A | p.N581I, p.I714N, p.V600E, p.R701I, p.G469A, p.L597Q | |

| BRCA1 | c.1961delA, c.66dupA | p.K654fs*47, p.E23fs*18 | |

| Non-EDM | BRCA2 | c.1813delA, c.5073delA, c.7007G>A, c.9072_9092delCAAC, c.9097delA | p.I605fs*9, p.K1691fs*15, p.R2336H, p.N3024_T3030, p.T3033fs*29 |

| CDH1 | c.549_554delCAAAGA, c.944dupA | p.D183 K184del, p.N315fs*6 | |

| CEBPA | c.564_566delGCC | p.P189del | |

| CHEK2 | c.1556C>T, c.562C>T | p.T519M, p.R188W | |

| CREBBP | c.5837delC | p.P1946fs*30 | |

| EGFR | c.2236_2250delGAATTAAG, c.2174C>T, c.2509G>A | p.E746_A750del, p.T725M, p.D837N | |

| EP300 | c.4408delA, c.6370dupG, c.4408delA, c.1425dupT | p.M1470fs*26, p.V2124fs*86, p.M1470fs*26, p.Q476fs*37 | |

| ERBB2 | c.2524G>A | p.V842I | |

| ERCC5 | c.2751delA | p.K917fs*65 | |

| FBXW7 | c.1436G>A | p.R479Q | |

| FGFR1 | c.396_398delTGA | p.D133del | |

| FGFR3 | c.1148delA, c.2128G>A, c.1150T>C | p.F383S, p.G710S, p.F384 L | |

| FLT4 | c.1267delC | p.Q423fs*70 | |

| IDH1 | c.394C>T | p.R132C | |

| IDH2 | c.419G>A | p.R140Q | |

| JAK2 | c.515G>A | p.R172Q | |

| JAK3 | c.1849G>T | p.V617F | |

| KIT | c.1880C>T, c.2447A>T | p.P627 L, p.D816V | |

| KRAS | c.38G>A, c.35G>C, c.182A>G, c.35G>A, c.35G>T, c.351A>C | p.G13D, p.G12A, p.Q61R, p.G12D, p.G12V, p.K117N | |

| MLH1 | c.676C>T | p.R226* | |

| MLH3 | c.2116delA, c.1755delA | p.T706fs28, p.E586fs*24 | |

| MSH3 | c.1148delA | p.K383fs*32 | |

| MSH6 | c.2314C>T, c.3261dupC | p.R772W, p.F1088fs*32 | |

| NRAS | c.34G>T, c.182A>T, c.35G>A, c.38G>A | p.G12C, p.Q61 L, p.G12D, p.G13D | |

| PALB2 | c.3201+1G>A | p.? | |

| PIK3CA | c.1634A>G, c.3140A>T, c.331A>G | p.E545G, p.H1047 L, p.K111E | |

| PIK3R1 | c.244delA, c.1690A>G | p.I82fs*32, p.N564D | |

| PMA2 | c.1239delA | p.D414fs*34 | |

| PMS2 | c.1239delA, c.630dupA | p.D414fs*34, p.R211fs*38 | |

| POLD1 | c.347delC | p.P116fs*53 | |

| POLD3 | c.898delA | p.R300fs*5 | |

| PTEN | c.19G>T, c.407G>A, c.802-2delA, c.802-2A>T, c.397G>A | p.E7*, p.C136Y, p.?, p.?, p.V133I | |

| RET | c.1900T>A | p.C634S | |

| SMAD4 | c.1094G>T | p.G365V | |

| TCF7 L2 | c.1385delA, c.1403delA | p.K462fs*23, p.K468fs*23 | |

| TGFBR2 | c.383dupA | p.P129fs*3 | |

| EDM | MLH3 | c.2116delA, c.1755delA | p.T706fs28, p.E586fs*24 |

| MSH3 | c.1148delA | p.K383fs*32 | |

In the MSI evaluation of POLE-mutant patients, IHC revealed that 168 cases (87.96%) were pMMR (MSI-L) and 23 cases (12.04%) were dMMR (MSI-H), whereas Real-time PCR classified 165 cases as MSI-L, 8 cases as MSS, and 18 cases as MSI-H. Concordance analysis demonstrated a good level of agreement between the two methods (Cohen’s kappa = 0.77). The observed discrepancies were primarily attributed to limitations in FFPE tissue quality and variability in tumor cell content.

We performed Fisher’s exact test to compare MSI-H frequency between POLE EDM and non-EDM groups (Table 4). No statistically significant difference was observed (P = 1.0).

| POLE mutation type | Total patients (n) | MSI-H (n) | MSS/MSI-L (n) | P value |

| EDM mutation | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Non-EDM mutation | 189 | 23 | 166 | |

| Total | 191 | 23 | 168 | P = 1.0 |

Table 5 provides stratified descriptive statistics of POLE-mutant CRC patients by age, tumor location, and MSI status, including the most frequent co-mutations. EDM mutations were extremely rare (n = 2), whereas the majority of POLE mutations were non-EDM (n = 189). Among POLE-mutant patients, MSI-H was observed in 23 cases (12.04%), primarily among non-EDM mutations. POLE mutations were more common in the colon than in the rectum across all MSI categories. Age stratification showed that most patients were between 50-65 years old. The estimated odds ratio (OR) for MSI-H in EDM vs non-EDM cases was 0.03 (95%CI: 0.001-1.2, P = 0.06), highlighting the low prevalence of EDM mutations and the need for cautious interpretation. Co-mutation patterns, most frequently MLH3, MSH3, KRAS, PIK3CA, BRAF, PMS2, TP53, MSH6, ERCC5, and TCF7 L2, were mainly observed in non-EDM cases.

| POLE mutation | Patient (n) | MSI-H | MSS/MSI-L | Co-mutation | OR MSI-H | 95%CI | Colon (n) | Rectum (n) | Age (n) | ||

| < 50 years | 50-65 years | > 65 years | |||||||||

| EDM | 2 | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | - | 0.03 | 0.001 to | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Non-EDM | 189 | 23 (12.17) | 166 (87.83) | BRAF, ERCC5, KRAS, MLH3, MSH3, MSH6, PIK3CA, PMS2, TCF7 L2, TP53 | 1 (reference) | - | 150 | 39 | 50 | 100 | 39 |

| Total | 191 | 23 (12.04) | 168 (87.96) | - | - | - | 152 | 39 | 51 | 101 | 39 |

This study is the first to investigate POLE EDMs, non-EDMs, and accompanying mutations in Turkish patients with CRC, along with the MSI status of patients.

POLE mutations are generally considered significant genetic findings in various cancer types, including CRC. Over the past decade, studies have reported that somatic mutations in the POLE gene occur in 1%-12.3% of CRC cases, while POLE EDMs are present in only 1%-2% of cases[8,10,15]. For instance, Domingo et al[15] reported POLE mutations in only 1% of CRC patients, and similarly, Guo et al[10] found a 1.5% prevalence of POLE mutations in a Chinese CRC cohort. Both studies emphasized that these mutations contribute significantly to the genetic profile of the disease and are associated with a high mutational burden. The most notable finding in the present study was that POLE mutations were detected in 53.65% of CRC patients in the Turkish cohort, a proportion considerably higher than that reported in other populations. However, this high prevalence is largely driven by a single variant (p.V1446fs*3). When this variant is excluded from the analysis, the prevalence decreases to 2.53%, aligning more closely with the range reported in the literature (approximately 1%-12%). Therefore, the elevated POLE frequency observed in our study predominantly reflects the impact of a single variant with uncertain pathogenicity. Furthermore, the preferential use of NGS in patients with advanced-stage disease or suspected molecular alterations increases the risk of referral bias. Analytical factors (panel design, targeted regions, sequencing depth, and VAF thresholds) and population-specific genetic differences may also contribute to the observed high prevalence. These factors are not mutually exclusive and may act in combination. Accordingly, our findings should be interpreted with caution and validated in larger, multicenter cohorts.

Although there is insufficient evidence to support the pathogenic role of POLE non-EDMs, some studies have validated their pathogenic effects[16]. Stenzinger et al[8] identified somatic POLE non-EDMs in 12.3% of sporadic MSS CRC cases, and another study reported POLE non-EDMs in 3%-4% of CRC and endometrial cancers[9]. Consistent with the literature, our study found a POLE EDM rate of approximately 1%, whereas the frequency of POLE non-EDMs was higher than previously reported. As previously noted, this elevated rate may be attributed to referral bias, methodological differences, and potential population-specific genetic variations. In this study, the most frequently observed variant was the exon 34 c.4337_4338delTG p.V1446fs*3 frameshift variant, classified as having ‘Conflicting classifications of pathogenicity.’ This specific mutation has not been previously reported in CRC patients. Previous studies, such as Stenzinger et al[8] and Briggs et al[9], have reported different non-EDM mutations in CRC and endometrial cancer cohorts. This mutation represents the first POLE non-EDM variant with a high incidence in Turkish CRC patients and is generally associated with a high mutational burden. Our study also reports the frequency of other POLE non-EDM and EDM variants, and understanding the pathogenic effects of these variants is particularly important for informing therapeutic approaches. While our findings expand the mutational spectrum of POLE in CRC, larger-scale studies including different Turkish CRC subgroups, as well as functional analyses (such as in vitro expression, cell proliferation/apoptosis assays, and replication error/DNA repair efficiency tests) are warranted to clarify the biological impact and generalizability of this variant.

Excluding potentially recurrent mutations in CRC, other distinct variants have also been listed in the literature for POLE. Most of these variants are present in the EDM and include mutations, such as p.W347C, p.N363Ks, p.D368V, p.K425R, p.P436S, and p.Y458F[17]. Among them, p.D368V and p.Y458F were functionally verified[18-22]. In the current study, POLE EDMs identified in patients included the p.Y458F and p.Y468N variants. The p.Y458F variant has been classified as a class 5 pathogenic variant of CRC, as reported by Rocque et al[23]. The p.Y468N variant (classified as "uncertain significance") identified in our patients represents the first reported POLE EDM in the Turkish population. However, the frequency of EDMs was lower than that of the non-EDMs. This discrepancy could be due to population differences and the limited number of studies that detected non-EDMs.

The incidence of somatic POLE mutations has been reported to be higher in patients with colon cancer than in those with rectal cancer[24,25]. Similarly, in our study, the mutation incidence was higher in colon cancer, which is consistent with the literature.

Two methods are generally used for MSI detection: First, molecular analysis of MSI markers by PCR; and second, evaluation of the expression of four MMR proteins in histological sections by IHC. In the literature, discordances between these two methods have been rarely reported, particularly in cases with mutations in MMR proteins, POLE mutations, or MLH1 promoter methylation, where IHC results may be inconclusive[26-30]. In such cases, molecular MSI testing is recommended for confirmation[14]. In our study, concordance between IHC and PCR results was assessed using Cohen’s kappa, which was calculated as 0.77, indicating a “good level of agreement” between the two methods. In most dis

The frequency of dMMR/MSI-H tumors in patients with CRC is approximately 15%-20%, with stage IV dMMR/MSI-H tumors representing only 2%-4% of all metastatic CRC cases[31]. In our study, a similar rate was observed, with 12.04% of CRC patients showing a dMMR/MSI-H status, which is consistent with literature.

The identification of 87.96% of POLE-mutant patients as having MSI-L indicates a strong association between these mutations and MSI-L. Carethers et al[31], POLE mutations are typically associated with an ultra-mutated phenotype but not necessarily with MSI-H, which is consistent with our finding that most POLE-mutant tumors were MSI-L. In our study, no statistically significant association was observed between MSI status and EDM or non-EDM mutations. This finding is likely due to the insufficient number of patients with EDM mutations.

In our cohort, the frequent co-occurrence of POLE mutations with variants in MLH3, MSH3, KRAS, PIK3CA, and BRAF is noteworthy. These co-mutation patterns point to several possible biological mechanisms. DNA repair pathways (MMR genes: MLH3, MSH3, PMS2, MSH6): Co-mutations in these genes, together with POLE alterations, may exacerbate DNA repair deficiencies, driving tumors toward an ultra-mutated phenotype. This may, in turn, enhance sensitivity to immune checkpoint inhibitors[2,15,16,24]. Oncogenic signaling pathways (KRAS, PIK3CA, BRAF): Mutations in the MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways, when combined with the mutational burden induced by POLE alterations, may increase immunogenicity and tumor heterogeneity[30,31]. Tumor suppressor genes (TP53, PTEN, SMAD4): Additional mutations in these genes may contribute to loss of cell cycle control and the development of a more aggressive tumor phenotype[15,31]. These patterns indicate that POLE mutations shape tumor biology not in isolation, but in concert with co-mutations. Clinically, such combinatorial mutation profiles may help to identify patient subgroups most likely to benefit from immunotherapy and may guide the discovery of novel therapeutic targets[16,24,30]. Specifically, the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes MLH3 and MSH3, when present alongside POLE mutations, are suggested to further impair DNA repair capacity, potentially increasing tumor mutational burden (TMB) and genomic instability[22,32]. CRC-specific studies have demonstrated that POLE mutations, particularly EDMs combined with MLH3/MSH3 mutations, are associated with high TMB and MSI-H phenotypes[32,33]. Although data on non-EDM POLE mutations are more limited, recent CRC studies have reported that these variants, when occurring together with MMR genes, may also exacerbate DNA repair deficiencies and contribute to MSI-like phenotypes in certain subgroups[34,35]. Therefore, not only EDMs but also non-EDM mutations may have potential biological significance in the presence of MLH3/MSH3 co-mutations. In conclusion, although survival data were not available in our study, the literature suggests that POLE mutations in CRC - particularly when co-occurring with MLH3/MSH3 - may increase DNA repair deficiencies, elevate TMB, and influence sensitivity to immunotherapy. In light of these findings, it is reasonable to propose the hypothesis that POLE mutations accompanied by MLH3/MSH3 alterations may further impair DNA repair capacity not only in the presence of EDM variants but also when non-EDM variants are involved. The co-occurrence of POLE + MLH3/MSH3 observed in our study may be better explained by a model that includes contributions from non-EDMs, rather than being limited to classical EDM variants. However, the uncertainties regarding the pathogenic impact of non-EDM variants and their contribution to DNA repair deficiency highlight the need for further biological investigations in this area. In particular, large CRC-specific genomic sequencing datasets (e.g., TCGA-COADREAD, MSK-CRC panels) should be systematically analyzed to assess the prevalence of non-EDM POLE variants, their co-mutation distribution, impact on TMB, and associations with survival and treatment response.

Our study not only highlights the high frequency of POLE mutations but also emphasizes the importance of their associated co-mutation profiles. Evaluating POLE mutations in conjunction with MSI status and co-mutations may help better identify candidates for immunotherapy[15,16]. Although the pathogenic effects of POLE non-EDMs have not been fully established, their high prevalence observed in our study suggests potential impacts on CRC biology. The frequent co-occurrence of these mutations with key genes may influence tumor immunogenicity and supports the exploration of combination therapeutic approaches (e.g., immunotherapy plus targeted therapies)[26]. Even without functional validation, these findings provide a foundation for future studies aimed at assessing the prognostic and therapeutic significance of non-EDMs.

This study is subject to several important limitations. The apparently high prevalence of POLE mutations (53.65%) was primarily driven by a single variant of uncertain pathogenicity (p.V1446fs3); exclusion of this variant reduced the prevalence to 2.53%. Additional factors such as referral bias, differences in NGS panels, and population-specific genetic features may also have contributed. Due to its retrospective design, stage-specific analyses of POLE mutation frequency could not be performed. Furthermore, the very limited number of patients carrying EDM variants posed a significant restriction in assessing associations between POLE mutations and clinicopathological parameters. The cohort consisted exclusively of CRC patients from a single institution in Türkiye, which further limits the external generalizability of the findings. Importantly, the functional impact of POLE non-EDM variants was not experimentally validated in this study. Of note, the most frequent variant (p.V1446fs3) has been inconsistently classified regarding pathogenicity, underscoring the need for functional validation through approaches such as cell culture and DNA repair assays. The relatively small size of the POLE-mutant subgroup, together with the limited MSI-H subset, weakened the power of subgroup and stratification analyses. In particular, the presence of only two patients harboring EDM variants rendered stratified evaluations underpowered. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted with caution. To strengthen the evidence base, multicenter studies or pooled data approaches (e.g., meta-analyses) are warranted. Finally, long-term clinical outcomes such as disease-free survival and treatment response could not be assessed, due to the retrospective nature of the study and incomplete follow-up data. This limitation precluded evaluation of the prognostic and therapeutic implications of POLE mutations-particularly non-EDM variants-and restricts their current clinical utility.

In this study, POLE mutations, particularly non-EDM variants, were highly prevalent in a Turkish CRC cohort, mostly in MSI-L tumors. The most frequent non-EDM variant (exon 34 c.4337_4338delTG p.V1446fs*3) has unverified pathogenicity and unknown functional impact. POLE mutations often co-occurred with MLH3, MSH3, KRAS, PIK3CA, and BRAF, potentially exacerbating DNA repair deficiencies and affecting tumor biology. These findings suggest that both EDM and non-EDM POLE variants may play an important role in CRC and could serve as potential biomarkers; functional validation and multicenter studies are needed to clarify the pathogenic effects of non-EDM variants.

| 1. | Lin A, Zhang J, Luo P. Crosstalk Between the MSI Status and Tumor Microenvironment in Colorectal Cancer. Front Immunol. 2020;11:2039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 45.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ma X, Dong L, Liu X, Ou K, Yang L. POLE/POLD1 mutation and tumor immunotherapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022;41:216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kawai T, Nyuya A, Mori Y, Tanaka T, Tanioka H, Yasui K, Toshima T, Taniguchi F, Shigeyasu K, Umeda Y, Fujiwara T, Okawaki M, Yamaguchi Y, Goel A, Nagasaka T. Clinical and epigenetic features of colorectal cancer patients with somatic POLE proofreading mutations. Clin Epigenetics. 2021;13:117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Siraj AK, Bu R, Iqbal K, Parvathareddy SK, Masoodi T, Siraj N, Al-Rasheed M, Kong Y, Ahmed SO, Al-Obaisi KAS, Victoria IG, Arshad M, Al-Dayel F, Abduljabbar A, Ashari LH, Al-Kuraya KS. POLE and POLD1 germline exonuclease domain pathogenic variants, a rare event in colorectal cancer from the Middle East. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020;8:e1368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ham-Karim HA, Ahmad NS, Ilyas M. Exploring somatic mutations in POLE and POLD1: Their role in colorectal cancer pathogenesis and potential therapeutic strategies. Tumor Discov. 2024;3:3659. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Flecchia C, Zaanan A, Lahlou W, Basile D, Broudin C, Gallois C, Pilla L, Karoui M, Manceau G, Taieb J. MSI colorectal cancer, all you need to know. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2022;46:101983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jiang M, Jia Y, Han J, Shi J, Su C, Zhang R, Xing M, Jin S, Zong H. Distinct clinical pattern of colorectal cancer patients with POLE mutations: A retrospective study on real-world data. Front Genet. 2022;13:963964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Stenzinger A, Pfarr N, Endris V, Penzel R, Jansen L, Wolf T, Herpel E, Warth A, Klauschen F, Kloor M, Roth W, Bläker H, Chang-Claude J, Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Weichert W. Mutations in POLE and survival of colorectal cancer patients--link to disease stage and treatment. Cancer Med. 2014;3:1527-1538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Briggs S, Tomlinson I. Germline and somatic polymerase ε and δ mutations define a new class of hypermutated colorectal and endometrial cancers. J Pathol. 2013;230:148-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Guo Y, Guo XL, Wang S, Chen X, Shi J, Wang J, Wang K, Klempner SJ, Wang W, Xiao M. Genomic Alterations of NTRK, POLE, ERBB2, and Microsatellite Instability Status in Chinese Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Oncologist. 2020;25:e1671-e1680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fang H, Barbour JA, Poulos RC, Katainen R, Aaltonen LA, Wong JWH. Mutational processes of distinct POLE exonuclease domain mutants drive an enrichment of a specific TP53 mutation in colorectal cancer. PLoS Genet. 2020;16:e1008572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mosalem O, Coston TW, Imperial R, Mauer E, Thompson C, Yilma B, Bekaii-Saab TS, Stoppler MC, Starr JS. A comprehensive analysis of POLE/POLD1 genomic alterations in colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2024;29:e1224-e1227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Agarwal P, Le DT, Boland PM. Immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2021;151:137-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Erdogdu IH, Orenay-Boyacioglu S, Boyacioglu O, Kahraman-Cetin N, Guler H, Turan M, Meteoglu I. Microsatellite instability and somatic gene variant profile in solid organ tumors. Arch Med Sci. 2024;20:1672-1679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Domingo E, Freeman-Mills L, Rayner E, Glaire M, Briggs S, Vermeulen L, Fessler E, Medema JP, Boot A, Morreau H, van Wezel T, Liefers GJ, Lothe RA, Danielsen SA, Sveen A, Nesbakken A, Zlobec I, Lugli A, Koelzer VH, Berger MD, Castellví-Bel S, Muñoz J; Epicolon consortium, de Bruyn M, Nijman HW, Novelli M, Lawson K, Oukrif D, Frangou E, Dutton P, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M, Kerr R, Kerr D, Tomlinson I, Church DN. Somatic POLE proofreading domain mutation, immune response, and prognosis in colorectal cancer: a retrospective, pooled biomarker study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:207-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Garmezy B, Gheeya J, Lin HY, Huang Y, Kim T, Jiang X, Thein KZ, Pilié PG, Zeineddine F, Wang W, Shaw KR, Rodon J, Shen JP, Yuan Y, Meric-Bernstam F, Chen K, Yap TA. Clinical and Molecular Characterization of POLE Mutations as Predictive Biomarkers of Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Advanced Cancers. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6:e2100267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Esteban-Jurado C, Giménez-Zaragoza D, Muñoz J, Franch-Expósito S, Álvarez-Barona M, Ocaña T, Cuatrecasas M, Carballal S, López-Cerón M, Marti-Solano M, Díaz-Gay M, van Wezel T, Castells A, Bujanda L, Balmaña J, Gonzalo V, Llort G, Ruiz-Ponte C, Cubiella J, Balaguer F, Aligué R, Castellví-Bel S. POLE and POLD1 screening in 155 patients with multiple polyps and early-onset colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:26732-26743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chubb D, Broderick P, Frampton M, Kinnersley B, Sherborne A, Penegar S, Lloyd A, Ma YP, Dobbins SE, Houlston RS. Genetic diagnosis of high-penetrance susceptibility for colorectal cancer (CRC) is achievable for a high proportion of familial CRC by exome sequencing. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:426-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hansen MF, Johansen J, Bjørnevoll I, Sylvander AE, Steinsbekk KS, Sætrom P, Sandvik AK, Drabløs F, Sjursen W. A novel POLE mutation associated with cancers of colon, pancreas, ovaries and small intestine. Fam Cancer. 2015;14:437-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Palles C, Cazier JB, Howarth KM, Domingo E, Jones AM, Broderick P, Kemp Z, Spain SL, Guarino E, Salguero I, Sherborne A, Chubb D, Carvajal-Carmona LG, Ma Y, Kaur K, Dobbins S, Barclay E, Gorman M, Martin L, Kovac MB, Humphray S; CORGI Consortium; WGS500 Consortium, Lucassen A, Holmes CC, Bentley D, Donnelly P, Taylor J, Petridis C, Roylance R, Sawyer EJ, Kerr DJ, Clark S, Grimes J, Kearsey SE, Thomas HJ, McVean G, Houlston RS, Tomlinson I. Germline mutations affecting the proofreading domains of POLE and POLD1 predispose to colorectal adenomas and carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2013;45:136-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 766] [Cited by in RCA: 778] [Article Influence: 59.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Valle L, Hernández-Illán E, Bellido F, Aiza G, Castillejo A, Castillejo MI, Navarro M, Seguí N, Vargas G, Guarinos C, Juarez M, Sanjuán X, Iglesias S, Alenda C, Egoavil C, Segura Á, Juan MJ, Rodriguez-Soler M, Brunet J, González S, Jover R, Lázaro C, Capellá G, Pineda M, Soto JL, Blanco I. New insights into POLE and POLD1 germline mutations in familial colorectal cancer and polyposis. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:3506-3512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bellido F, Pineda M, Aiza G, Valdés-Mas R, Navarro M, Puente DA, Pons T, González S, Iglesias S, Darder E, Piñol V, Soto JL, Valencia A, Blanco I, Urioste M, Brunet J, Lázaro C, Capellá G, Puente XS, Valle L. POLE and POLD1 mutations in 529 kindred with familial colorectal cancer and/or polyposis: review of reported cases and recommendations for genetic testing and surveillance. Genet Med. 2016;18:325-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rocque MJ, Leipart V, Kumar Singh A, Mur P, Olsen MF, Engebretsen LF, Martin-Ramos E, Aligué R, Sætrom P, Valle L, Drabløs F, Otterlei M, Sjursen W. Characterization of POLE c.1373A > T p.(Tyr458Phe), causing high cancer risk. Mol Genet Genomics. 2023;298:555-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hino H, Shiomi A, Kusuhara M, Kagawa H, Yamakawa Y, Hatakeyama K, Kawabata T, Oishi T, Urakami K, Nagashima T, Kinugasa Y, Yamaguchi K. Clinicopathological and mutational analyses of colorectal cancer with mutations in the POLE gene. Cancer Med. 2019;8:4587-4597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Guerra J, Pinto C, Pinto D, Pinheiro M, Silva R, Peixoto A, Rocha P, Veiga I, Santos C, Santos R, Cabreira V, Lopes P, Henrique R, Teixeira MR. POLE somatic mutations in advanced colorectal cancer. Cancer Med. 2017;6:2966-2971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | van Lier MG, Wagner A, van Leerdam ME, Biermann K, Kuipers EJ, Steyerberg EW, Dubbink HJ, Dinjens WN. A review on the molecular diagnostics of Lynch syndrome: a central role for the pathology laboratory. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:181-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Shia J. Immunohistochemistry versus microsatellite instability testing for screening colorectal cancer patients at risk for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome. Part I. The utility of immunohistochemistry. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:293-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 466] [Cited by in RCA: 501] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hissong E, Crowe EP, Yantiss RK, Chen YT. Assessing colorectal cancer mismatch repair status in the modern era: a survey of current practices and re-evaluation of the role of microsatellite instability testing. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:1756-1766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sarode VR, Robinson L. Screening for Lynch Syndrome by Immunohistochemistry of Mismatch Repair Proteins: Significance of Indeterminate Result and Correlation With Mutational Studies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143:1225-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lin EI, Tseng LH, Gocke CD, Reil S, Le DT, Azad NS, Eshleman JR. Mutational profiling of colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability. Oncotarget. 2015;6:42334-42344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Carethers JM, Jung BH. Genetics and Genetic Biomarkers in Sporadic Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1177-1190.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Alexandrov LB, Kim J, Haradhvala NJ, Huang MN, Tian Ng AW, Wu Y, Boot A, Covington KR, Gordenin DA, Bergstrom EN, Islam SMA, Lopez-Bigas N, Klimczak LJ, McPherson JR, Morganella S, Sabarinathan R, Wheeler DA, Mustonen V; PCAWG Mutational Signatures Working Group, Getz G, Rozen SG, Stratton MR; PCAWG Consortium. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature. 2020;578:94-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2218] [Cited by in RCA: 2506] [Article Influence: 417.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Campbell BB, Light N, Fabrizio D, Zatzman M, Fuligni F, de Borja R, Davidson S, Edwards M, Elvin JA, Hodel KP, Zahurancik WJ, Suo Z, Lipman T, Wimmer K, Kratz CP, Bowers DC, Laetsch TW, Dunn GP, Johanns TM, Grimmer MR, Smirnov IV, Larouche V, Samuel D, Bronsema A, Osborn M, Stearns D, Raman P, Cole KA, Storm PB, Yalon M, Opocher E, Mason G, Thomas GA, Sabel M, George B, Ziegler DS, Lindhorst S, Issai VM, Constantini S, Toledano H, Elhasid R, Farah R, Dvir R, Dirks P, Huang A, Galati MA, Chung J, Ramaswamy V, Irwin MS, Aronson M, Durno C, Taylor MD, Rechavi G, Maris JM, Bouffet E, Hawkins C, Costello JF, Meyn MS, Pursell ZF, Malkin D, Tabori U, Shlien A. Comprehensive Analysis of Hypermutation in Human Cancer. Cell. 2017;171:1042-1056.e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 529] [Cited by in RCA: 599] [Article Influence: 66.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Castellanos E, Gel B, Rosas I, Tornero E, Santín S, Pluvinet R, Velasco J, Sumoy L, Del Valle J, Perucho M, Blanco I, Navarro M, Brunet J, Pineda M, Feliubadaló L, Capellá G, Lázaro C, Serra E. A comprehensive custom panel design for routine hereditary cancer testing: preserving control, improving diagnostics and revealing a complex variation landscape. Sci Rep. 2017;7:39348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Legrand C, Lebrun M, Naïbo P, Peysselon M, Prieur F, Kientz C, Desseigne F, Handallou S, Rey JM, Nambot S, Goussot V, Hamzaoui N, Wang Q. A novel POLD1 pathogenic variant identified in two families with a cancer spectrum mimicking Lynch syndrome. Eur J Med Genet. 2022;65:104409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/