Published online Nov 28, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i44.112719

Revised: September 14, 2025

Accepted: October 24, 2025

Published online: November 28, 2025

Processing time: 115 Days and 17.6 Hours

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients rarely achieve functional cure with initial pegylated interferon alpha-2b (Peg-IFNα-2b) therapy. Validated tools to guide retreatment candidates are lacking. We hypothesized that clinical indicators predict hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) clearance during retreatment.

To develop a prediction model for HBsAg clearance in Peg-IFNα-2b retreatment.

In this retrospective cohort study, we enrolled 135 CHB/compensated cirrhosis patients receiving Peg-IFNα-2b retreatment after initial non-clearance at Tianjin University Central Hospital (2017-2025). Predictors were identified through univariate Cox, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator, and multivariate Cox regression. Model performance was assessed via receiver operating characteristic analysis and Harrell’s C-index, with risk stratification by X-tile optimization.

HBsAg clearance rate was 20.74% (28/135). Independent predictors included: Combination nucleos(t)ide analogue (NA) therapy during initial treatment [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.276, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.092-0.833], baseline HBsAg at retreatment (HR = 0.571, 95%CI: 0.410-0.795), HBsAg decline after initial treatment (HR = 2.050, 95%CI: 1.108-3.793), and treatment interval (HR = 1.013/week, 95%CI: 1.008-1.018). The retreatment HBsAg clearance prediction score (RHCP-S) demonstrated area under the curve of 0.920 (95%CI: 0.863-0.946), sensitivity of 92.3%, specificity of 79.3%. Clearance rates differed significantly: RHCP-S challenge group (≤ 74 points): 3.45%, RHCP-S probable group (74-110 points): 29.63%, RHCP-S dominant group (≥ 110 points): 80.95% (P < 0.001).

The overall HBsAg clearance rate with Peg-IFNα-2b retreatment was 20.74% (28/135). The RHCP-S model identifies optimal retreatment candidates (≥ 110 points) with 80.95% clearance probability, associated with the absence of combination NA therapy during initial treatment, greater initial HBsAg decline, longer intervals, and lower retreatment HBsAg.

Core Tip: This pioneering study developed the first predictive model (retreatment hepatitis B surface antigen clearance prediction score) for hepatitis B surface antigen clearance during pegylated interferon retreatment in chronic hepatitis B. Analyzing 135 patients, we found that retreatment candidates scoring ≥ 110 points achieved dramatically higher clearance rates (81% vs 3.45% in low-scorers). Key predictors included pegylated interferon monotherapy, substantial initial hepatitis B surface antigen decline, extended treatment intervals, and lower retreatment baseline hepatitis B surface antigen. The model enables precision selection to avoid futile therapy in 97% of non-responders.

- Citation: Fu YC, Li J, Wang JY, Zhang YW, Yan F, Chen J, Du Q, Yang C, Liang J, Ye Q, Xiang HL. Retreatment hepatitis B surface antigen clearance prediction model identifies pegylated interferon alpha candidates in chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(44): 112719

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i44/112719.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i44.112719

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection can lead to liver cirrhosis and related complications, including hepatocellular carcinoma[1]. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) clearance is closely associated with improved liver function, liver histopathology, and long-term prognosis, and is recommended by authoritative national and international guidelines as the ideal goal of antiviral therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB)[2,3]. At present, pegylated interferon alpha (Peg-IFNα)-based antiviral regimens are the main approach to achieving HBsAg clearance in CHB patients. Guidelines recommend a standard course of Peg-IFNα treatment for 48-72 weeks, but the HBsAg clearance rate after 48 weeks is approximately 20%-33%[4,5]. Extending the Peg-IFNα course to 96 weeks can increase the HBsAg clearance rate by 15%-30%[6-9]. However, not all patients benefit from extended treatment. Some patients experience a plateau phase during Peg-IFNα treatment, where HBsAg levels cease to decline or even begin to rise. Once this plateau phase is reached, extended treatment often yields minimal benefit. Retreatment after a treatment-free interval may help overcome the plateau through immune function recovery[6,7], but there is limited research on Peg-IFNα retreatment. This study, based on a Peg-IFNα retreatment cohort, aims to identify the factors influencing HBsAg clearance during retreatment and provide evidence for accurately identifying dominant populations for retreatment.

This was a single-center, retrospective, observational study. Patients with CHB and compensated liver cirrhosis (CLC) who were treated at the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology of Tianjin University Central Hospital (Tianjin Third Central Hospital) between January 2017 and April 2025 were enrolled.

Inclusion criteria: (1) HBsAg positivity for at least 6 months; (2) Received an initial course of Peg-IFNα-2b (Pegbing®, Xiamen Amoytop Biotech Co., Ltd.) monotherapy or combination therapy with nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs) without achieving HBsAg clearance; (3) Received another course of Peg-IFNα-2b monotherapy or in combination with NAs after a treatment-free interval; and (4) Interval between the two Peg-IFNα-2b treatments ≥ 12 weeks.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Chronic liver disease due to current infection with hepatitis A virus, hepatitis C virus, hepatitis E virus, and/or human immunodeficiency virus; (2) Chronic liver disease with concurrent hepatocellular carcinoma; (3) Contraindications to Peg-IFNα treatment; (4) Patients who achieved HBsAg clearance after the initial treatment but experienced recurrence; (5) Missing data for key timepoints; and (6) Loss to follow-up. CHB and CLC were diagnosed according to the Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of CHB (2022 Edition)[10].

HBsAg clearance during the second course of Peg-IFNα-2b monotherapy or combination therapy with NAs, or up to the end of the observation period on April 31, 2025.

Patients were divided into two groups based on whether HBsAg clearance was achieved after Peg-IFNα-2b retreatment: HBsAg positive (HBSP) group and HBsAg negative (HBSN) group.

Demographic data, baseline characteristics from the initial treatment, laboratory and imaging findings, the start and end times of both treatment courses, and virological indicators at baseline/week 12/end of both courses were collected.

Calculation of HBsAg decline at week 12 and at the end of the initial treatment, and rebound magnitude of HBsAg level at the beginning of retreatment compared to baseline/end of initial treatment.

Formulas used in this study: (1) HBsAg decline at week 12 of initial treatment = baseline HBsAg level of initial treatment - HBsAg level at week 12; (2) HBsAg decline at end of initial treatment = baseline HBsAg level of initial treatment - HBsAg level at end of treatment; (3) Percentage of HBsAg decline at end of initial treatment = HBsAg decline at end of initial treatment/baseline HBsAg level; (4) Rebound magnitude of HBsAg at retreatment baseline compared to baseline of initial treatment = (HBsAg level at retreatment baseline - baseline HBsAg level of initial treatment)/baseline HBsAg level of initial treatment; and (5) Rebound magnitude of HBsAg at retreatment baseline compared to end of initial treatment = (HBsAg level at retreatment baseline - HBsAg level at end of initial treatment)/HBsAg level at end of initial treatment.

HBsAg: Tested using the Abbott ARCHITECT i4000SR system (Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL, United States) based on chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay technology, with a lower limit of detection of 0.05 IU/mL. HBV DNA: Two methods were used in this study: (1) Automated nucleic acid amplification and detection with the TaqMan48 analyzer (Roche, Pleasanton, CA, United States) using fluorescent polymerase chain reaction (PCR), detection range: 20-1.7 × 108 IU/mL; and (2) Xiamen Ample Anadas9850 real-time fluorescent PCR system, detection range: 50-5.0 × 108 IU/mL.

Liver function tests (alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, total bilirubin, albumin) and complete blood count (platelet) were performed using automatic biochemical and hematological analyzers (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan).

Liver stiffness measurement and controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) were assessed using the FibroScan® transient elastography system (Echosens, France).

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median (Q1, Q3), and categorical variables as counts (percentages). Differences in continuous variables were analyzed using t-tests or Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum tests, and categorical variables using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. Predictor selection was performed in three stages: (1) Univariate Cox regression screening (P < 0.05); (2) Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression (10-fold cross-validation, λ = 0.054) to reduce high-dimensional data; and (3) Multivariate Cox regression (adjusted for sex and age) to identify core predictors. A nomogram was constructed to visualize the model. Model performance was evaluated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The X-tile software (maximum χ² principle) was used to determine optimal cutoff values for dominant group stratification. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests were used to assess differences in HBsAg clearance rates between groups (P < 0.001). Model robustness was validated using Harrell’s C-index and 1000 bootstrap resamples. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P value < 0.05. Analyses were performed using R version 4.4.3 and EmpowerStats software, and figures were generated using Origin 2024.

To facilitate clinical implementation of the retreatment HBsAg clearance prediction score (RHCP-S) model, we developed an interactive web calculator using the R Shiny framework. The tool is permanently accessible via Zenodo (doi: 10.5281/zenodo.15736857) or directly at: https://rhcp-s.shinyapps.io/RHCP-S/. The calculator is designed to accept raw clinical measurements and automatically performs all necessary logarithmic transformations, minimizing input errors. Clinicians can input the required parameters to instantaneously receive the RHCP-S score, risk stratification, predicted clearance probability, and evidence-based clinical management advice. This tool is device-agnostic and requires no software installation, functioning on any modern web browser across desktops, tablets, and smartphones.

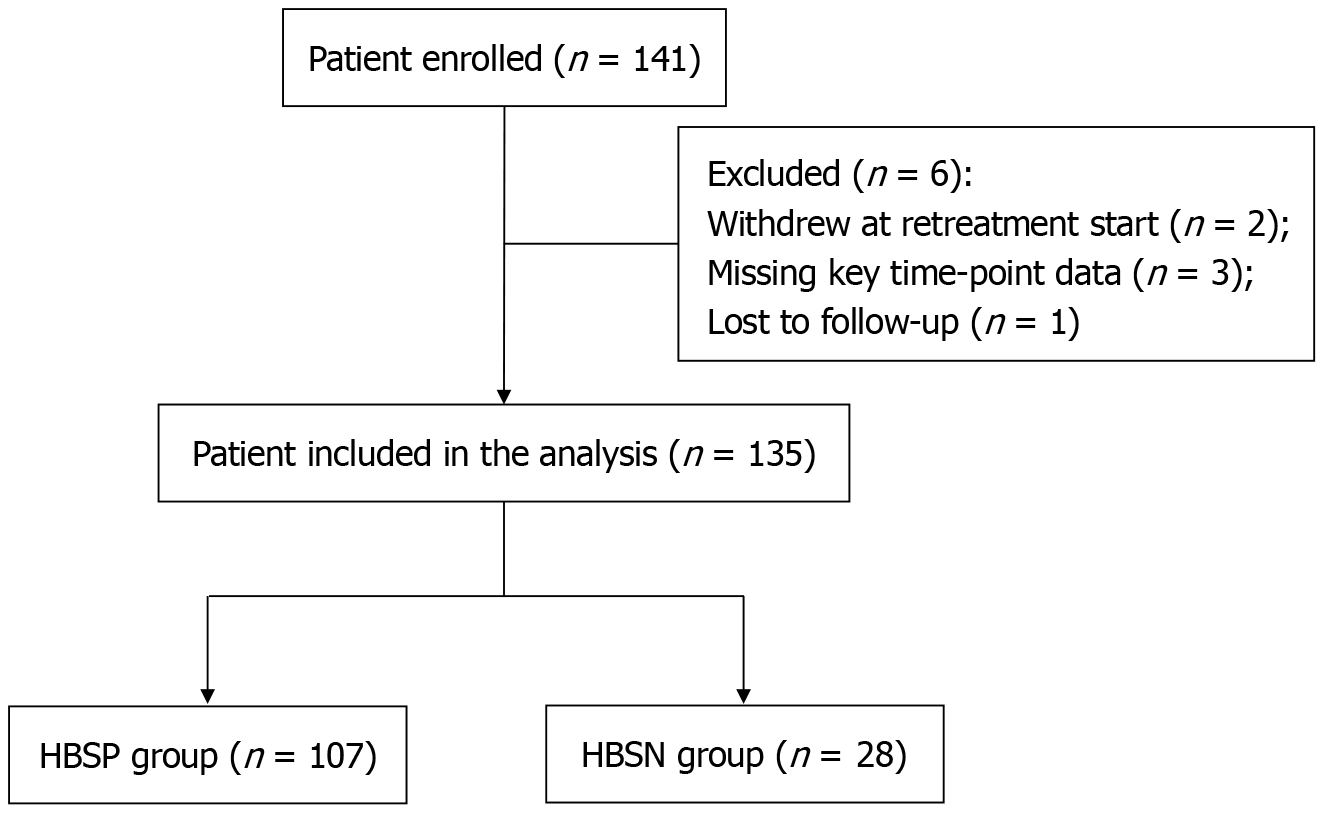

A total of 141 CHB and CLC patients who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled in this study. After excluding 2 patients who withdrew at the start of retreatment, 3 patients with missing data at key time points, and 1 patient lost to follow-up, 135 patients were finally included in the analysis. Among them, 107 were in the HBSP group and 28 in the HBSN group, with an HBsAg clearance rate of 20.74% after retreatment (Figure 1).

A total of 135 CHB patients were included in this study, with a median age of 40.00 (35.00-46.00) years, of whom 74.07% were male. The median body mass index was 24.70 (22.80-26.60) kg/m², and 24.44% (33/135) were diagnosed with CLC. Significant differences (P < 0.05) were observed between the HBSP and HBSN groups in the following indicators: Use and type of NAs during the initial treatment, baseline CAP value of initial treatment, baseline HBsAg level of initial treatment, week 12 HBsAg level and its decline of initial treatment, HBsAg level at end of initial treatment, HBsAg decline magnitude and percentage at end of initial treatment; The interval weeks between the two treatments; Duration of Peg-IFNα-2b in retreatment; HBsAg level at retreatment baseline and rebound magnitude compared to both baseline and end of the initial treatment. No significant differences were found in other indicators (see Table 1 for details).

| Characteristic | Total patients (n = 135) | HBSP (n = 107) | HBSN (n = 28) | P value |

| Age (years), median (Q1, Q3) | 40.00 (35.00, 46.00) | 40.00 (35.00, 47.00) | 38.50 (35.75, 41.00) | 0.311 |

| Male | 100 (74.07) | 80 (74.77) | 20 (71.43) | 0.720 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (Q1, Q3) | 24.70 (22.80, 26.60) | 24.75 (23.02, 26.78) | 24.70 (22.35,25.90) | 0.388 |

| HBV family history | 0.203 | |||

| No | 59 (44.70) | 44 (41.90) | 15 (55.56) | |

| Yes | 73 (55.30) | 61 (58.10) | 12 (44.44) | |

| Smoke history | 0.836 | |||

| No | 38 (65.52) | 30 (63.83) | 8 (72.73) | |

| Yes | 20 (34.48) | 17 (36.17) | 3 (27.27) | |

| Drink history | 0.848 | |||

| No | 49 (84.48) | 39 (82.98) | 10 (90.91) | |

| Yes | 9 (15.52) | 8 (17.02) | 1 (9.09) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.000 | |||

| No | 125 (94.70) | 99 (94.29) | 26 (96.30) | |

| Yes | 7 (5.30) | 6 (5.71) | 1 (3.70) | |

| Hypertension | 0.881 | |||

| No | 116 (87.88) | 93 (88.57) | 23 (85.19) | |

| Yes | 16 (12.12) | 12 (11.43) | 4 (14.81) | |

| Cirrhosis | 0.362 | |||

| No | 102 (75.56) | 79 (73.83) | 23 (82.14) | |

| Yes | 33 (24.44) | 28 (26.17) | 5 (17.86) | |

| First circle Peg-IFNα treatment relative | ||||

| Combination of NAs | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 8 (5.93) | 2 (1.87) | 6 (21.43) | |

| Yes | 127 (94.07) | 105 (98.13) | 22 (78.57) | |

| Type of NAs | 0.001 | |||

| No | 8 (5.93) | 2 (1.87) | 6 (21.43) | |

| ETV | 29 (21.48) | 27 (25.23) | 2 (7.14) | |

| TDF | 49 (36.29) | 39 (36.45) | 10 (35.72) | |

| TAF | 40 (29.63) | 32 (29.91) | 8 (28.57) | |

| Combine | 9 (6.67) | 7 (6.54) | 2 (7.14) | |

| Baseline HBsAg level of initial treatment (log10 IU/mL), median (Q1, Q3) | 3.23 (2.84, 3.59) | 3.32 (2.98, 3.71) | 2.92 (2.30, 3.18) | < 0.001 |

| HBsAg level at week 12 of initial treatment (log10 IU/mL), median (Q1, Q3) | 3.03 (2.35, 3.39) | 3.14 (2.67, 3.49) | 1.83 (0.87, 2.75) | < 0.001 |

| HBsAg level at end of initial treatment (log10 IU/mL), median (Q1, Q3) | 2.55 (1.44, 3.16) | 2.72 (1.82, 3.30) | 0.93 (0.30, 1.87) | < 0.001 |

| HBsAg decline at week 12 of initial treatment (log10 IU/mL), median (Q1, Q3) | 0.21 (0.07, 0.62) | 0.15 (0.03, 0.36) | 0.84 (0.32, 1.19) | < 0.001 |

| HBsAg decline at end of initial treatment (log10 IU/mL), median (Q1, Q3) | 0.65 (0.30, 1.42) | 0.50 (0.28, 0.93) | 1.64 (0.72, 1.97) | < 0.001 |

| HBsAg decline at end of initial treatment (%), median (Q1, Q3) | 0.78 (0.05, 0.96) | 0.69 (0.46, 0.88) | 0.98 (0.81, 0.99) | < 0.001 |

| HBeAg | 0.542 | |||

| Negative | 98 (73.13) | 77 (71.96) | 21 (77.78) | |

| Positive | 36 (26.87) | 30 (28.04) | 6 (22.22) | |

| HBV DNA (log10 IU/mL), median (Q1, Q3) | -3.00 (-3.00, 3.17) | -3.00 (-3.00, 3.04) | 2 .00 (-3.00, 3.39) | 0.323 |

| ALT (U/L), median (Q1, Q3) | 25.50 (19.00, 42.50) | 25.00 (17.00, 40.00) | 31.70 (19.00, 45.00) | 0.277 |

| AST (U/L), median (Q1, Q3) | 22.50 (18.00, 29.00) | 22.00 (18.00, 29.00) | 24.00 (18.00, 29.00) | 0.878 |

| GGT (U/L), median (Q1, Q3) | 24.00 (17.00, 38.75) | 24.00 (16.25, 39.75) | 24.00 (17.00, 35.00) | 0.928 |

| TBIL (μmol/L), median (Q1, Q3) | 16.40 (13.00, 21.63) | 16.85 (13.28, 22.02) | 15.25 (11.38,17.70) | 0.064 |

| ALB (g/L), median (Q1, Q3) | 48.40 (46.75, 49.95) | 48.15 (46.55, 50.00) | 48.90 (47.80, 49.80) | 0.319 |

| PLT (109/L), median (Q1, Q3) | 194.00 (164.25, 236.25) | 197.00 (166.00, 238.00) | 189.00 (165.00, 212.00) | 0.445 |

| AFP (IU/mL), median (Q1, Q3) | 2.68 (1.89, 4.58) | 2.76 (1.89, 4.63) | 2.51 (2.10, 4.25) | 0.637 |

| LSM (kPa), median (Q1, Q3) | 7.60 (6.00, 9.80) | 7.70 (6.17, 9.80) | 6.46 (5.65, 9.20) | 0.184 |

| CAP (dB/m), median (Q1, Q3) | 249.00 (231.00, 276.20) | 256.00 (232.00, 278.00) | 239.00 (228.75, 254.25) | 0.037 |

| Second circle Peg-IFNα treatment relative | ||||

| HBsAg level at retreatment baseline (log10 IU/mL), median (Q1, Q3) | 2.53 (1.67, 3.12) | 2.81 (2.02, 3.31) | 0.89 (-0.28, 2.31) | < 0.001 |

| Rebound magnitude of HBsAg at retreatment baseline compared to end of initial treatment (log10 IU/mL), median (Q1, Q3) | 0.00 (-0.14, 0.19) | 0.00 (-0.10, 0.16) | -0.03 (-0.54, 0.32) | 0.433 |

| Rebound magnitude of HBsAg at retreatment baseline compared to end of initial treatment (%), median (Q1, Q3) | 0.00 (-0.06, 0.07) | 0.00 (-0.04, 0.07) | -0.15 (-0.96, 0.08) | 0.027 |

| Rebound magnitude of HBsAg at retreatment baseline compared to baseline of initial treatment (%), median (Q1, Q3) | -0.20 (-0.43, -0.09) | -0.17 (-0.29, -0.08) | -0.63 (-1.10, -0.30) | < 0.001 |

| The interval weeks between the two treatments (weeks), median (Q1, Q3) | 23.40 (15.00, 39.85) | 20.70 (15.00, 32.95) | 36.40 (16.20, 86.17) | 0.015 |

| 1st Peg-IFN treatment course (weeks), median (Q1, Q3) | 48.00 (36.00, 58.70) | 48.00 (36.00, 55.35) | 39.40 (27.65, 51.50) | 0.824 |

| 2nd Peg-IFN treatment course (weeks), median (Q1, Q3) | 28.00 (21.25, 44.75) | 26.05 (19.02, 43.30) | 30.00 (19.55, 47.00) | 0.016 |

| Total follow-up time (weeks), median (Q1, Q3) | 147.60 (126.30, 182.05) | 155.10 (131.60, 182.05) | 134.95 (116.75, 178.78) | 0.181 |

Taking HBsAg clearance after retreatment as the endpoint and number of follow-up weeks as the time variable, univariate Cox regression, LASSO regression, and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed. Twelve potential predictive variables were identified via univariate Cox regression (P < 0.05) (Table 2). After further compression with LASSO regression (10-fold cross-validation, λ = 0.054), 6 variables were retained: Combination of NAs during the initial treatment, HBsAg decline at week 12 and at end of initial treatment, HBsAg level at end of initial treatment, interval weeks between the two treatment courses, and HBsAg level at retreatment baseline (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 1). Multivariate Cox regression finally identified four independent predictors: Combination of NAs during the initial treatment [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.276, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.092-0.833] and HBsAg level at retreatment baseline (HR = 0.571, 95%CI: 0.410-0.795) were unfavorable factors, reducing the probability of achieving HBsAg clearance by 72.4% and 42.9%, respectively. In contrast, HBsAg decline at end of initial treatment (HR = 2.050, 95%CI: 1.108-3.793) and the interval weeks between the two treatments (HR = 1.013, 95%CI: 1.008-1.018) were favorable factors. For every 1 log10 IU/mL increase in HBsAg decline at the end of the initial treatment, the probability of achieving HBsAg clearance after retreatment increased by 105%; for each additional week of interval between treatments, the probability increased by 1.3% (P < 0.05 for all, Table 2).

| Characteristic | Univariable | LASSO | Multivariable | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Age (years) | 0.979 (0.931-1.030) | 0.406 | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 1 | ||||

| Female | 1.185 (0.522-2.690) | 0.685 | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.945 (0.837-1.067) | 0.363 | |||

| HBV family history | |||||

| No | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 0.642 (0.301-1.373) | 0.254 | |||

| Smoke history | |||||

| No | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 0.785 (0.208-2.968) | 0.722 | |||

| Drink history | |||||

| No | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 0.562 (0.072-4.393) | 0.583 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | |||||

| No | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 0.742 (0.100-5.482) | 0.770 | |||

| Hypertension | |||||

| No | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1.444 (0.497-4.194) | 0.499 | |||

| Cirrhosis | |||||

| No | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 0.662 (0.252-1.742) | 0.404 | |||

| First circle Peg-IFNα treatment relative | |||||

| Combination of NAs | Yes | 0.022 | |||

| No | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 0.159 (0.064-0.394) | < 0.001 | 0.276 (0.092-0.833) | ||

| Type of NAs | |||||

| No | 1 | ||||

| ETV | 0.056 (0.011-0.280) | < 0.001 | |||

| TDF | 0.198 (0.072-0.546) | 0.002 | |||

| TAF | 0.188 (0.065-0.544) | 0.002 | |||

| Combine | 0.187 (0.038-0.933) | 0.041 | |||

| 1st Peg-IFNα treatment course (weeks) | 1.011 (0.986-1.037) | 0.394 | |||

| Baseline HBsAg level of initial treatment (log10 IU/mL) | 0.472 (0.324-0.686) | < 0.001 | |||

| HBsAg level at week 12 of initial treatment (log10 IU/mL) | 0.433 (0.329-0.569) | < 0.001 | |||

| HBsAg level at end of initial treatment (log10 IU/mL) | 0.474 (0.377-0.594) | < 0.001 | Yes | 1.024 (0.641-1.638) | 0.920 |

| HBsAg decline at week 12 of initial treatment (log10 IU/mL) | 4.043 (2.576-6.343) | < 0.001 | Yes | 1.113 (0.578-2.142) | 0.310 |

| HBsAg decline at end of initial treatment (log10 IU/mL) | 2.450 (1.748-3.434) | < 0.001 | Yes | 2.050 (1.108-3.793) | 0.028 |

| HBsAg decline at end of initial treatment (%) | 27.448 (3.286-29.246) | 0.002 | |||

| HBeAg | |||||

| Negative | 1 | ||||

| Positive | 0.706 (0.285-1.749) | 0.452 | |||

| HBV DNA (log10 IU/mL) | 1.047 (0.954-1.148) | 0.333 | |||

| ALT (U/L) | 1.001 (0.999-1.003) | 0.266 | |||

| AST (U/L) | 0.997 (0.989-1.005) | 0.501 | |||

| GGT (U/L) | 1.000 (0.994-1.006) | 0.965 | |||

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 0.989 (0.941-1.040) | 0.670 | |||

| ALB (g/L) | 1.063 (0.921-1.227) | 0.405 | |||

| PLT (109/L) | 0.998 (0.990-1.006) | 0.643 | |||

| AFP (ng/mL) | 0.966 (0.885-1.055) | 0.441 | |||

| LSM (kPa) | 0.919 (0.798-1.059) | 0.244 | |||

| CAP (dB/m) | 0.994 (0.987-1.001) | 0.109 | |||

| The interval weeks between the two treatments (weeks) | 1.010 (1.006-1.014) | < 0.001 | Yes | 1.013 (1.008-1.018) | < 0.001 |

| Second circle Peg-IFNα treatment relative | |||||

| HBsAg level at retreatment baseline (log10 IU/mL) | 0.440 (0.353-0.549) | < 0.001 | Yes | 0.571 (0.410-0.795) | 0.001 |

| Rebound magnitude of HBsAg at retreatment baseline compared to end of initial treatment (log10 IU/mL) | 0.757 (0.658-0.872) | < 0.001 | |||

| Rebound magnitude of HBsAg at retreatment baseline compared to end of initial treatment (%) | 0.682 (0.448-1.037) | 0.073 | |||

| Rebound magnitude of HBsAg at retreatment baseline compared to baseline of initial treatment (%) | 0.179 (0.107-0.300) | < 0.001 | |||

| Model parameter | λ = 0.054 | ||||

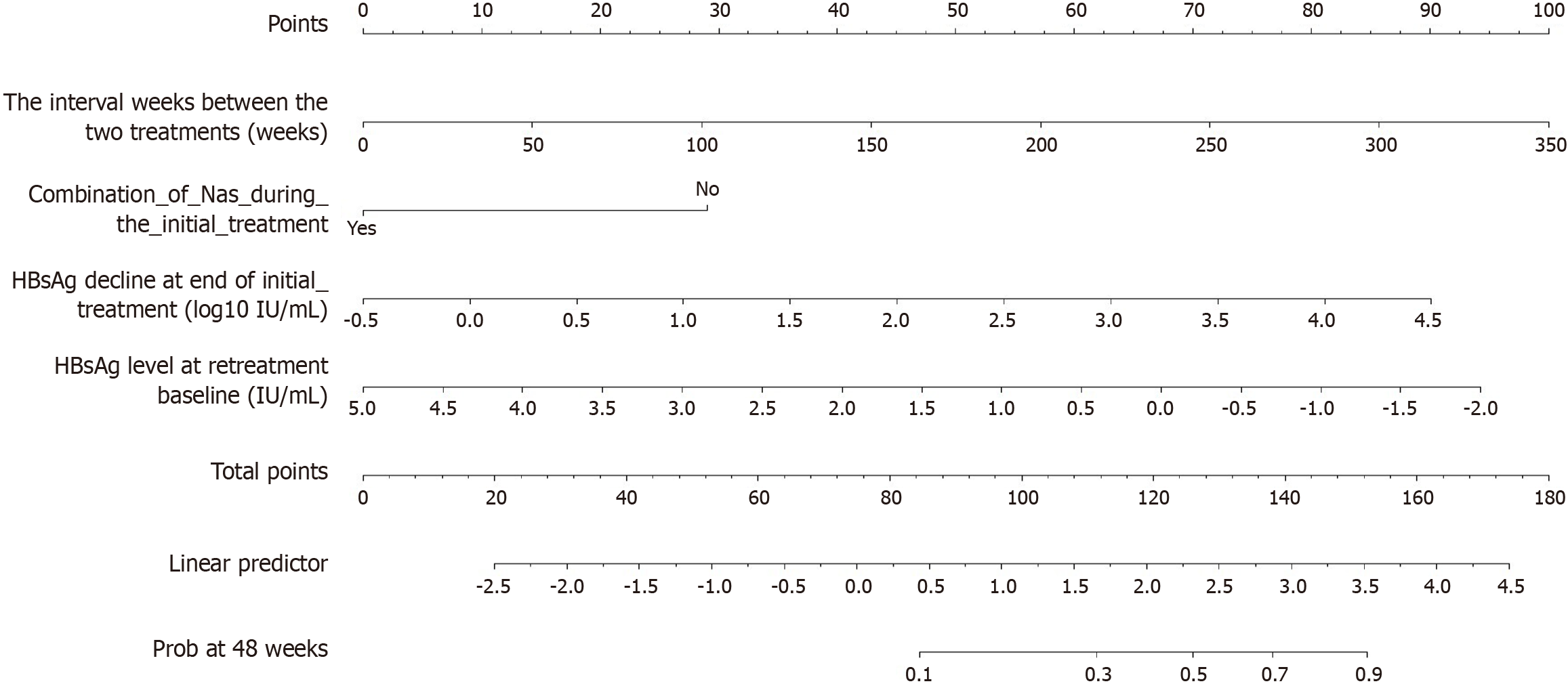

Based on the independent factors selected from the LASSO and multivariate Cox regression analyses, a nomogram model was developed to predict HBsAg clearance after Peg-IFNα-2b retreatment (Figure 2). From this, the RHCP-S was derived: RHCP-S = 18 × (HBsAg decline at end of initial treatment) - 29 × (combination of NAs during the initial treatment) + 0.29 × (the interval weeks between the two treatments) - 13.43 × (HBsAg level at retreatment baseline) + 105.15. This score was calculated by linearly transforming the prognostic index from the Cox model (scaling factor k = 21.971), with a constant term of 105.15 to ensure all patient scores are positive.

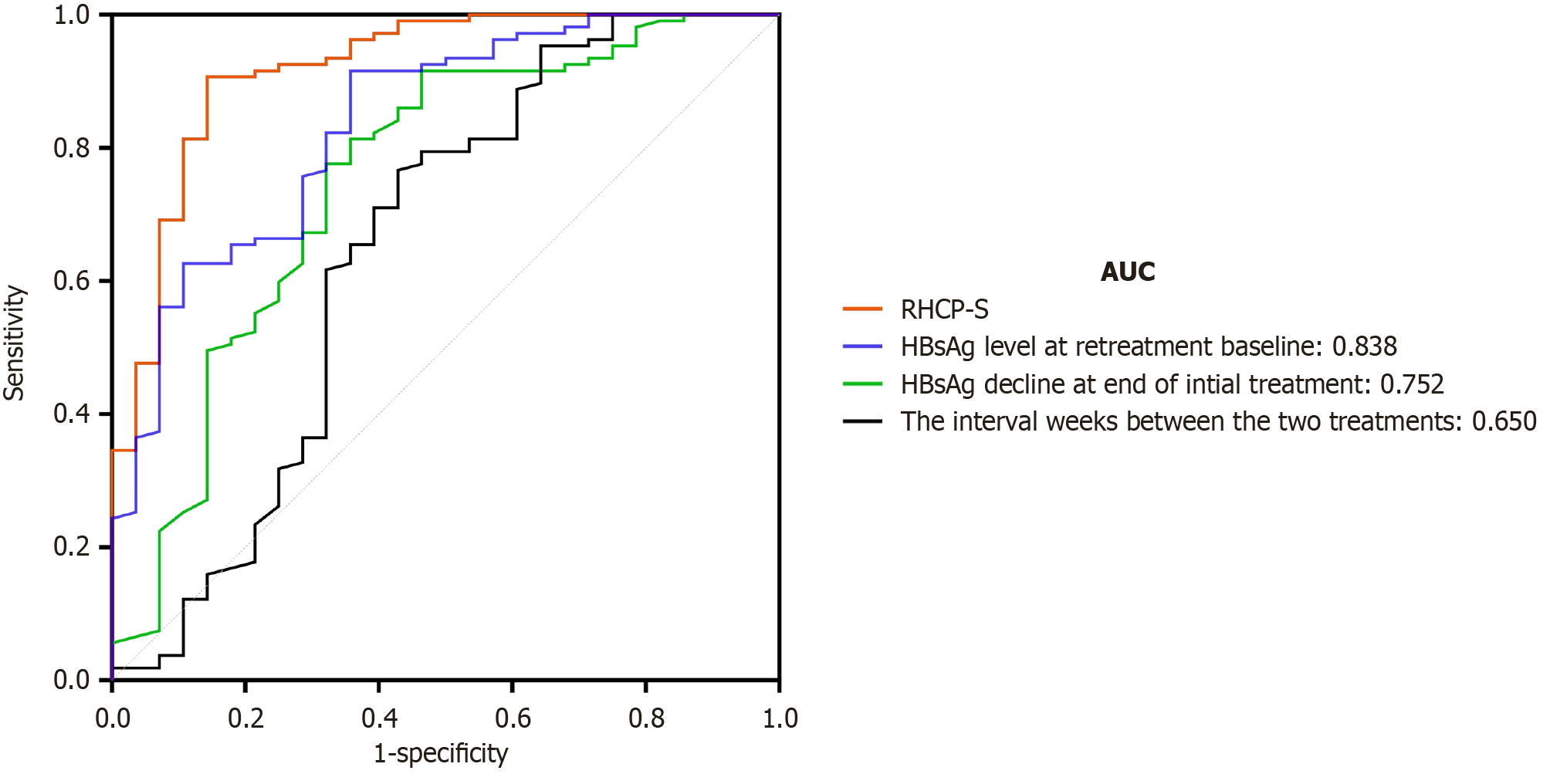

Time-dependent ROC analysis of the RHCP-S model showed an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.920 and a Harrell’s C-index of 0.905 (95%CI: 0.863-0.946), with a sensitivity of 92.3% and specificity of 79.3%. In comparison with the predictive performance of individual variables, RHCP-S (AUC = 0.920) > HBsAg level at retreatment baseline (AUC = 0.838) > HBsAg decline at end of initial treatment (AUC = 0.752) > the interval weeks between the two treatments (AUC = 0.650), indicating that the RHCP-S model has the best potential in identifying the population likely to achieve HBsAg clearance (see Figure 3).

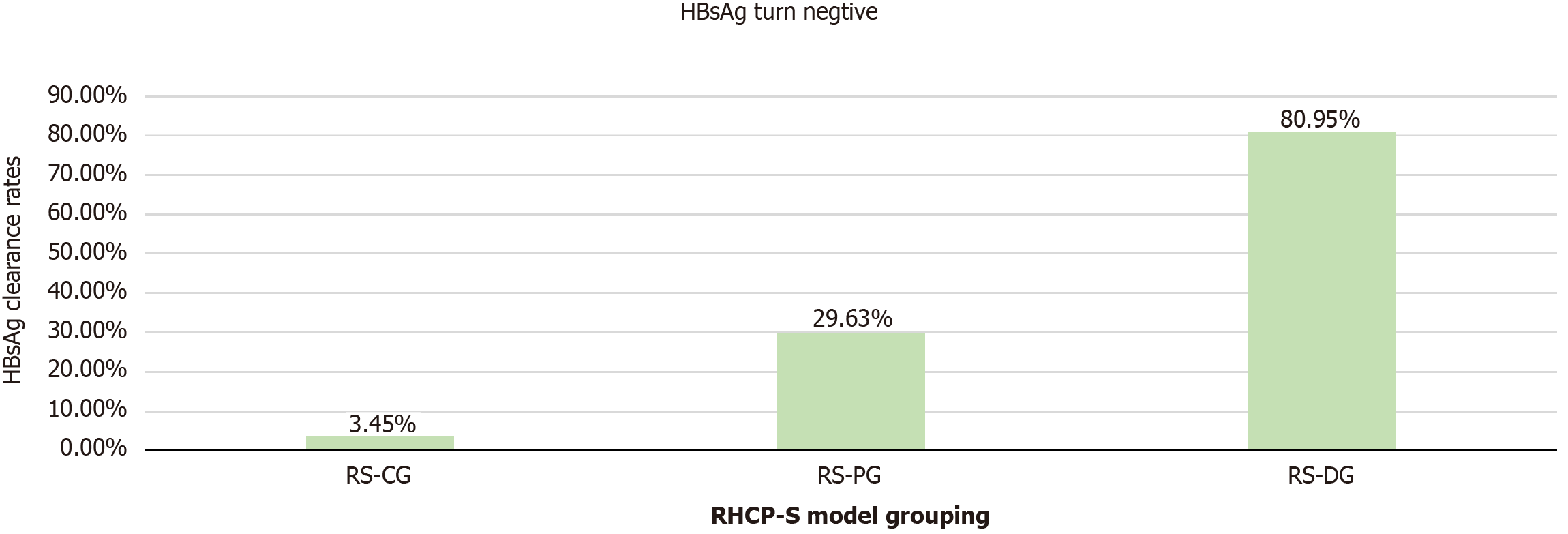

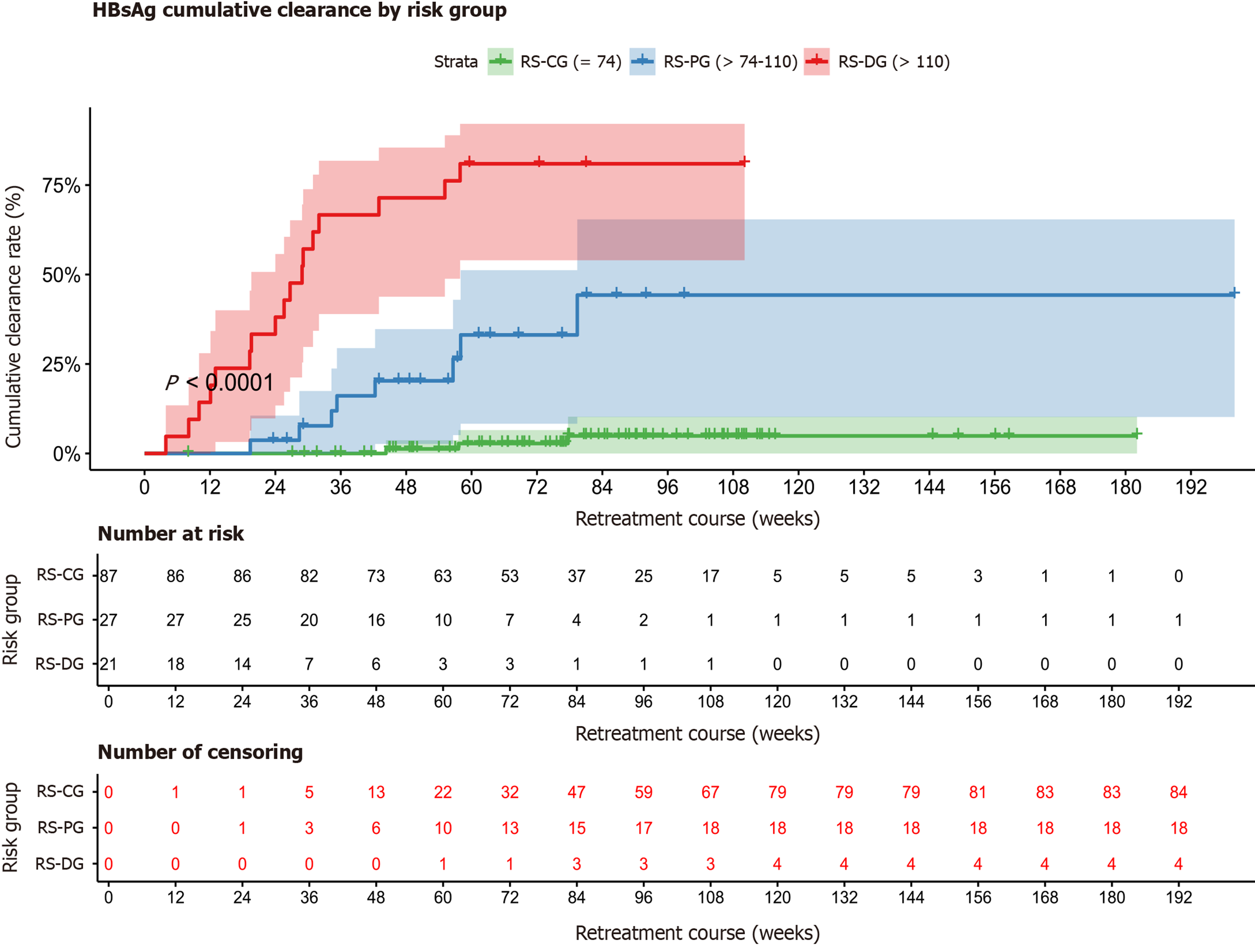

Based on the RHCP-S model, the optimal cutoff values of 74 and 110 were determined using X-tile software, dividing the patients into three groups: RHCP-S challenge group (RS-CG) (RHCP-S < 74, n = 87): HBsAg clearance rate of 3.45% (3/87); RHCP-S probable group (RS-PG) (74 ≤ RHCP-S < 110, n = 27): HBsAg clearance rate of 29.63% (8/27); RHCP-S dominant group (RS-DG) (RHCP-S ≥ 110, n = 21): HBsAg clearance rate of 80.95% (17/21) (Figure 4). To facilitate clinical implementation of the RHCP-S model, we developed an interactive web calculator using the R Shiny framework. The tool is permanently accessible via Zenodo or directly at: https://rhcp-s.shinyapps.io/RHCP-S/.

Kaplan-Meier curves further validated the stratification performance, showing significant differences in HBsAg clearance rates among the groups (P < 0.001) (Figure 5). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed a median HBsAg clearance time of 28.9 weeks (95%CI: 19.6-57.9) in the RS-DG group, while the RS-CG and RS-PG groups did not reach the median clearance time. Compared with the RS-CG group, the probabilities of achieving HBsAg clearance after Peg-IFNα-2b retreatment were 10.38 times higher in the RS-PG group (HR = 11.38, 95%CI: 3.01-43.04) and 55.72 times higher in the RS-DG group (HR = 56.72, 95%CI: 16.20-198.63), with all comparisons corrected using the Bonferroni method (P < 0.001). These results validate the stratification performance of the RHCP-S model in predicting HBsAg clearance following Peg-IFNα-2b retreatment (Supplementary Table 1 and Figure 5).

CHB remains a major global health burden, with approximately 257 million people chronically infected with HBV and over 880000 deaths annually from HBV-related end-stage liver diseases (cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma)[11,12]. Although NAs can effectively suppress viral replication, the risk of liver cancer persists. Multiple clinical guidelines have indicated that complete control of HBV, clearance of HBsAg, and achievement of clinical cure in CHB patients can maximally reduce the risks of hepatic decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver-related mortality, and is considered the ideal endpoint of antiviral therapy for CHB patients[13]. HBsAg is closely associated with intrahepatic covalently closed circular DNA, and its clearance reflects effective immune control of HBV replication. Peg-IFNα-based antiviral therapy is currently one of the main strategies for achieving HBsAg clearance. However, conventional 48-week Peg-IFNα treatment only leads to HBsAg clearance in approximately 20%-33% of patients[4,5]. Extending Peg-IFNα treatment to 96 weeks can improve the clearance rate[6-9], but not all patients benefit from prolonged therapy. Some patients enter a “plateau phase” during Peg-IFNα treatment, in which HBsAg levels stop declining or even increase. Once the plateau phase is reached, further treatment extension often yields little benefit. Therefore, the concept of intermittent therapy has been proposed.

Intermittent therapy refers to the approach in which Peg-IFNα is administered in a “treatment-interruption-retreatment” pattern, based on continuous NA therapy, with the aim of ultimately achieving HBsAg clearance. This strategy is commonly applied in patients whose HBsAg levels plateau during Peg-IFNα treatment. The emergence of a plateau phase during Peg-IFNα treatment may be related to depletion of Peg-IFNα receptors, reduced activity of cytotoxic natural killer cell subsets, decreased numbers of mature T cells, and cluster of differentiation 8+ T cell exhaustion[14,15]. As the duration of Peg-IFNα discontinuation increases, natural killer cell subsets gradually recover, and immune cell phenotypes and functions return to pre-treatment levels after 12-24 weeks of drug withdrawal[15]. Clinical studies have reported that a 12-24 weeks interval may help restore immune function and overcome the plateau phase[6,7]. This study found that the interval period was significantly associated with HBsAg clearance upon retreatment (HR = 1.015, P < 0.001). Each additional week of interval increased the HBsAg clearance rate by 1.5% during retreatment, further supporting the above findings. However, the optimal interval duration requires further investigation.

The results of this study showed that the overall HBsAg clearance rate following Peg-IFNα retreatment was 20.74%, which is consistent with data reported in the literature[14]. This suggests that not all patients benefit from Peg-IFNα retreatment, and a substantial proportion still fail to achieve HBsAg clearance even after undergoing another course of therapy. Wu et al[16] found that a lower baseline HBsAg level at the start of Peg-IFNα retreatment was associated with a higher HBsAg clearance rate. The study by Li et al[14] confirmed that intermittent Peg-IFNα therapy could result in an HBsAg clearance rate of 19.41% in patients experiencing a plateau phase, with early responders achieving a rate as high as 44.06%. Additionally, baseline HBsAg level at retreatment and a decline of > 0.5 Log10 IU/mL at week 12 were identified as independent predictors of HBsAg clearance. These findings collectively suggest that patients with a lower baseline HBsAg level at retreatment and a favorable response during the initial treatment are more likely to achieve HBsAg clearance upon Peg-IFNα retreatment. This study further validated that both the baseline HBsAg level at retreatment and the magnitude of HBsAg decline during the initial treatment are key predictive indicators, underscoring the need to comprehensively evaluate the response to the first course of treatment along with the baseline status prior to restarting Peg-IFNα therapy.

Our results indicated that the magnitude of HBsAg decline from baseline at the end of initial treatment, the interval weeks between the two treatments, whether NAs were combined during the first course, and the baseline HBsAg level at retreatment were all significantly associated with HBsAg clearance upon Peg-IFNα retreatment. Based on these variables, we constructed a predictive model RHCP-S for HBsAg clearance following Peg-IFNα retreatment and performed precise stratification of the retreatment population. In the RS-DG group (RHCP-S ≥ 110), the HBsAg clearance rate reached 80.95%. In the RS-PG group (74 ≤ RHCP-S < 110), the clearance rate was 29.63%, whereas in the RS-CG group (RHCP-S < 74), the likelihood of clearance was only 3.45%. The median time to clearance in the RS-DG group was 28.9 weeks. Compared with the RS-CG group, the probability of achieving HBsAg clearance upon Peg-IFNα retreatment was increased by 10.38 times in the RS-PG group and by 55.72 times in the RS-DG group (P < 0.001), suggesting that the RHCP-S model can effectively identify the advantageous population for HBsAg clearance through Peg-IFNα retreatment.

This study also found that the HBsAg clearance rate after retreatment was significantly higher in the group that initially received Peg-IFNα monotherapy compared to the group that received Peg-IFNα combined with NAs. This phenomenon may be related to clinical selection bias: Patients in the monotherapy group had more favorable baseline characteristics (e.g., lower HBsAg levels and negative HBV DNA), and thus were already in a population more likely to respond to Peg-IFNα.

We acknowledge several limitations of this study. First, as a single-center retrospective analysis with a modest sample size (n = 135, including only 28 clearance events), our findings may be subject to selection bias, limited statistical power, and reduced generalizability. Second, the subgroup of patients receiving initial Peg-IFNα monotherapy was very small (n = 8); thus, the observed association between monotherapy and superior outcomes may be confounded by baseline differences rather than representing a true therapeutic effect, and this finding requires validation in larger cohorts. Furthermore, while we have developed a web-based calculator to facilitate clinical application, this tool requires prospective validation in real-world settings to evaluate its impact on clinical decision-making and patient outcomes.

In summary, this study confirmed that patients who did not achieve HBsAg clearance after the initial course of Peg-IFNα therapy may still achieve clearance through retreatment. Patients with a greater decline in HBsAg from baseline at the end of initial treatment, longer interval between treatment courses, lower baseline HBsAg levels at retreatment, and those who initially received Peg-IFNα monotherapy are more likely to benefit from retreatment. The RHCP-S system, constructed based on the above indicators, can accurately identify the population most likely to benefit from retreatment, thereby avoiding ineffective treatment, reducing patient burden, and minimizing healthcare costs. Future multicenter studies with larger sample sizes are needed to validate our findings and establish broader clinical applicability externally.

In conclusion, this study establishes that CHB patients failing initial pegylated interferon therapy can achieve functional cure through retreatment, particularly those exhibiting greater HBsAg decline post-initial therapy, extended treatment intervals, lower baseline HBsAg at retreatment, and initial pegylated interferon monotherapy. The novel RHCP-S model precisely identifies optimal candidates (≥ 110 points) with 81% clearance probability while avoiding futile retreatment in 97% of low-responders (≤ 74 points). We recommend clinical implementation of this stratification tool to maximize retreatment success and reduce unnecessary healthcare burden, pending validation in multicenter cohorts.

We extend our sincere gratitude to the patients who participated in this study and to the clinical investigators from the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Tianjin University Central Hospital (formerly Tianjin Third Central Hospital), Tianjin, China.

| 1. | Jeng WJ, Lok ASF. What will it take to cure hepatitis B? Hepatol Commun. 2023;7:e0084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kao JH, Jeng WJ, Ning Q, Su TH, Tseng TC, Ueno Y, Yuen MF. APASL guidance on stopping nucleos(t)ide analogues in chronic hepatitis B patients. Hepatol Int. 2021;15:833-851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Anderson RT, Choi HSJ, Lenz O, Peters MG, Janssen HLA, Mishra P, Donaldson E, Westman G, Buchholz S, Miller V, Hansen BE. Association Between Seroclearance of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen and Long-term Clinical Outcomes of Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:463-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tan Z, Kong N, Zhang Q, Gao X, Shang J, Geng J, You R, Wang T, Guo Y, Wu X, Zhang W, Qu L, Zhang F. Predictive model for HBsAg clearance rate in chronic hepatitis B patients treated with pegylated interferon α-2b for 48 weeks. Hepatol Int. 2025;19:358-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wei N, Zheng B, Cai H, Li N, Yang J, Liu M. Systematic review and meta-analysis: de novo combination of nucleos(t)ide analogs and pegylated interferon alpha versus pegylated interferon alpha monotherapy for the functional cure of chronic hepatitis B. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1403805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 6. | Cao Z, Liu Y, Ma L, Lu J, Jin Y, Ren S, He Z, Shen C, Chen X. A potent hepatitis B surface antigen response in subjects with inactive hepatitis B surface antigen carrier treated with pegylated-interferon alpha. Hepatology. 2017;66:1058-1066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 7. | Bao X, Guo J, Xiong F, Qu Y, Gao Y, Gu N, Lu J. Clinical characteristics of chronic hepatitis B cured by peginterferon in combination with nucleotide analogs. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96:562-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Li MH, Lu HH, Chen QQ, Lin YJ, Zeng Z, Lu Y, Zhang L, Dong JP, Yi W, Xie Y. Changes in the Cytokine Profiles of Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B during Antiviral Therapy. Biomed Environ Sci. 2021;34:443-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lin YJ, Sun FF, Zeng Z, Bi XY, Yang L, Li MH, Xie Y. Combination and Intermittent Therapy Based on Pegylated Interferon Alfa-2a for Chronic Hepatitis B with Nucleoside (Nucleotide) Analog-Experienced Resulting in Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Clearance: A Case Report. Viral Immunol. 2022;35:71-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 10. | You H, Sun YM, Zhang MY, Nan YM, Xu XY, Li TS, Wang GQ, Hou JL, Duan ZP, Wei L, Wang FS, Jia JD, Zhuang H. [Interpretation of the essential updates in guidelines for the prevention and treatment of chronic hepatitis B (Version 2022)]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2023;31:385-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hou JL, Wei L, Wang GQ, Jia JD, Duan ZP, Zhuang H. [Clinical cure of hepatitis B: consensus and controversy]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2020;28:636-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | GBD 2019 Hepatitis B Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of hepatitis B, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:796-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 416] [Cited by in RCA: 515] [Article Influence: 128.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Wang ZL, Zheng JR, Yang RF, Huang LX, Chen HS, Feng B. An Ideal Hallmark Closest to Complete Cure of Chronic Hepatitis B Patients: High-sensitivity Quantitative HBsAg Loss. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2023;11:197-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Li M, Xie S, Bi X, Sun F, Zeng Z, Deng W, Jiang T, Lin Y, Yang L, Lu Y, Zhang L, Yi W, Xie Y. An optimized mode of interferon intermittent therapy help improve HBsAg disappearance in chronic hepatitis B patients. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:960589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Bi X, Xie S, Wu S, Cao W, Lin Y, Yang L, Jiang T, Deng W, Wang S, Liu R, Gao Y, Shen G, Chang M, Hao H, Xu M, Chen X, Hu L, Lu Y, Zhang L, Xie Y, Li M. Changes of natural killer cells' phenotype in patients with chronic hepatitis B in intermittent interferon therapy. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1116689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wu F, Wang Y, Cui D, Tian Y, Lu R, Liu C, Li M, Li Y, Gao N, Jiang Z, Li X, Zhai S, Zhang X, Jia X, Dang S. Short-Term Peg-IFN α-2b Re-Treatment Induced a High Functional Cure Rate in Patients with HBsAg Recurrence after Stopping Peg-IFN α-Based Regimens. J Clin Med. 2023;12:361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/