Published online Nov 28, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i44.112833

Revised: September 28, 2025

Accepted: October 27, 2025

Published online: November 28, 2025

Processing time: 113 Days and 13.7 Hours

Colorectal surgery is often associated with a high risk of anastomotic leakage. Intraoperative administration of dexmedetomidine (DEX) can improve posto

To investigate the effects of DEX on anastomotic healing in a rat model of intes

Rats were randomly divided into three groups: Sham (underwent abdominal only opening and closure), IA, and IA + DEX. In the IA + DEX group, DEX (5 μg/kg) was administered via tail vein infusion one day before and after anesthesia. Intestinal function, inflammation, and barrier integrity were measured based on intestinal propulsion, anastomotic burst pressure, histopathological analysis, im

Compared with IA, IA + DEX showed a non-significant increase in intestinal propulsion on postoperative day 6 and a significant rise in anastomotic burst pressure on day 7. Histology indicated reduced inflammation and submucosal injury. Serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha and diamine oxidase decreased, while tight junction pro

DEX enhances anastomotic healing and barrier function after IA, partly via Wnt/β-catenin activation, indicating therapeutic potential to improve postoperative outcomes.

Core Tip: Dexmedetomidine (DEX), a selective α2-adrenergic agonist, significantly enhances anastomotic healing in rat models of colon surgery. Our study demonstrates that perioperative DEX administration improves intestinal barrier integrity by upregulating tight junction proteins (claudin-1/zonula occludens-1), reduces systemic inflammation (suppressed tumor necrosis factor-alpha/diamine oxidase/intestinal fatty acid-binding protein), and increases anastomotic burst pressure. Crucially, we identify activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway as a novel mechanistic driver for DEX-mediated repair. These findings reveal DEX’s dual role in barrier protection and regeneration, supporting its potential as a perioperative adjuvant to mitigate anastomotic leakage risk in abdominal surgery.

- Citation: Chen Y, Li CT, Wang JB, Tang WL, Zhao Y, Chen Y, Liao LM, Zhang LC, Lin TH, Cao ZF. Dexmedetomidine enhances anastomotic healing partly via the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in a rat model of colon surgery. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(44): 112833

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i44/112833.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i44.112833

Colorectal surgery is the most common treatment method for colorectal cancer and bowel obstruction. Anastomotic leakage (AL) is one of the most serious complications after colorectal surgeries[1,2]. It is characterized by an anastomotic defect in the intestinal wall that enables communication between the intraluminal and extraluminal spaces. AL may cause peritoneal infection and even sepsis, undermining the quality of life and survival of patients. Buchs et al[3] reported an overall AL rate of 3.8%, with a mortality rate of 12.9%. Veyrie et al[4] found that the overall AL rate was 4% and the overall mortality was 4.1% in patients with colon cancer undergoing surgery. AL delays adjuvant therapy in cancer patients and negatively affects anti-cancer treatment outcomes[1,2]. AL after colorectal surgery represents a critical clinical issue that deserves attention. Several factors affect the incidence of postoperative AL, including surgical techniques, patient’s age, tumor location, and preoperative bowel preparation. Although the incidence of AL has recently decreased thanks to the efforts of gastrointestinal surgeons, novel perioperative management strategies are still needed to lower the risk of AL[1-4].

Dexmedetomidine (DEX) is a potent, highly selective α2-receptor agonist with sedative, anxiolytic, analgesic, and anesthetic effects[5,6]. DEX shortens ventilation and recovery times and lowers the incidence of hypertension and tachycardia. Interestingly, intraoperative administration of DEX can improve postoperative gastrointestinal function[7]. The use of DEX after laparoscopic colorectal resection has been shown to significantly reduce the time to defecation and gas elimination, allowing patients to return to a normal diet sooner[8]. Administering DEX with ropivacaine in the transversus abdominis plane block before laparoscopic colectomy was shown to significantly decrease the time to receive oral diet compared to ropivacaine transversus abdominis plane block alone[9]. In a recent multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, the DEX group had a significantly shorter time to first flatus, time to first feces, and length of hospital stay than the placebo group. A meta-analysis showed that perioperative administration of DEX can downregulate the production of interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein (CRP), indicating that DEX can inhibit perioperative inflammation[10]. These studies indicate that DEX is a promising strategy for enhancing postoperative gastrointestinal recovery[11]. While DEX’s anti-inflammatory and barrier-protective effects are well-documented, its role in modulating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway to enhance anastomotic healing remains unexplored, representing a novel therapeutic mechanism.

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of DEX on anastomotic healing in a rat model of colorectal surgery and to explore the underlying mechanisms. Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which is significantly upregulated after intestinal injury, promotes rapid epithelial cell proliferation to restore the mucosal barrier, while its inhibition delays repair and reduces proliferation, and exogenous Wnt activation enhances recovery[12,13]. As epithelial proliferation, restoration of mucosal barrier, and modulation of inflammation are fundamental to anastomotic healing, we hypothesized that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway mediates the effects of DEX on anastomotic healing.

Sixty-three male Sprague-Dawley rats (6 weeks old) were purchased from Changsha Keruibang Biotechnology Co. Rats were pair-housed under a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Ambient temperature and relative humidity were maintained at 21-25 °C and 40%-60%, respectively. Food and water were available ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the Guangzhou Boyao Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (No. IAEC-K-240314-02).

The intestinal anastomosis (IA) model was established as previously described[14]. All rats were fasted for one day before surgery. A 3% isoflurane (2 L/minute) was delivered until the rats were sedated. We placed them on an operating table with a heating pad, and delivered 1%-2% isoflurane (1 L/minute) to maintain the depth of anesthesia. The rats’ abdomens were shaved and sterilized with 70% ethanol and chlorhexidine. A 2 cm incision was performed along the abdominal midline. The skin, muscle, and peritoneum were cut layer by layer. The descending and sigmoid colon were exposed and identified by rotating the left-sided viscera medially. A cut was made across 80%-90% of the width of the colon. The colostomy was repaired with 6 interrupted stitches before closing the abdominal incision. In case of bleeding, gentle pressure was applied for 1-2 minutes. During the recovery period, rats were monitored for any signs of abscess and infection. Postoperatively, 0.2 mL of 80000 U penicillin sodium solution was injected intramuscularly. The sham group underwent abdominal opening and closure after general anesthesia but did not undergo IA.

All rats were housed in cages with soft bedding postoperatively and maintained on a heating pad until full recovery from anesthesia. For postoperative analgesia, meloxicam (4 mg/kg/day; Yuanye Bio-Technology, Shanghai, China; Cat. No. B67003) was administered subcutaneously for three days after surgery. Gel diet (Xietong Bio, Jiangsu Province, China; Cat. No. XTW01-003) was provided on postoperative days 1 and 2, followed by resumption of standard pre-operative chow. Rats were monitored daily for signs of surgical complications (dyspnea, reduced activity, wound dehiscence, hunched posture, etc.), and immediate euthanasia was implemented if surgical complications were observed. None of these signs were observed in the study cohort.

DEX hydrochloride (Meida Kanghuakang Co., Ltd, Sichuan Province, China) was diluted to 1 μg/mL with saline. Rats were randomly assigned to one of the 3 groups (n = 30 in each group). In the IA + DEX group, 5 μg/kg DEX was infused via the tail vein one day before the surgery and after general anesthesia. In the sham group and the IA group, 5 mL/kg saline was given in the same way. DEX dosage of 5 μg/kg was selected based on a previous study[15]. On postoperative day 5, six rats per group were randomly selected and fasted overnight for the intestinal propulsion test. The following day (day 7), another six rats per group were euthanized by carbon dioxide (CO2) inhalation, and a 2 cm intestinal segment containing the anastomosis was excised to measure anastomotic burst pressure. Blood samples were collected from the dorsal pedal vein of six randomly selected rats per group at designated time points (postoperative days 1, 3, 5, and 7), with an equivalent volume of normal saline replenished after each withdrawal; serum was separated and stored at -80 °C until enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). On days 3 and 7, anastomotic tissues were harvested from six rats per group after euthanasia and fixed for paraffin embedding. Furthermore, on day 3, three additional rats per group were euthanized, and anastomotic tissues were divided: One portion was preserved in RNAlater for transcriptomic analysis, and the other was snap-frozen at -80 °C for Western blotting.

On day 5, six rats were randomly selected underwent 24 hours of fasting. The following day (day 6), animals received a semi-solid paste (1 mL/100 g body weight). Thirty minutes after administration, all rats were anesthetized via isoflurane inhalation and euthanized using CO2 asphyxiation. The intestines were harvested to measure propulsion. The total length of the small intestine (L1) and the distance traversed by the charcoal front (L2) were measured. Intestinal propulsion over 30 minutes was calculated as follows: Propulsion (%) = L2/L1 × 100%.

Six rats were randomly selected on day 7 and euthanized by CO2 inhalation. The anastomotic intestinal tubes were removed. One end of the intestinal tube was connected to the syringe extension tube on a push pump, and the other end was connected to an arterial pressure measuring device to determine the pressure inside the intestinal tube. Saline was infused into the intestinal tube at 300 mL/hour using a push pump. A gradual increase in the intestinal pressure was observed until the intestinal tube could not withstand the internal pressure and burst. The highest pressure in the intestinal tube was recorded as the anastomotic intestinal burst pressure.

Rat serum TNF-α (Meimian Co., Ltd., China; Cat. No. MM-0180R1), diamine oxidase (DAO) (Saipei Co., Ltd., China; Cat. No. SP12787), and intestinal fatty acid-binding protein (iFABP) (Saipei Co., Ltd., China; Cat. No. SP12736) were quantified following kit protocols. IL-1β (Jiangsu Meimian Industrial Co., Ltd., China; Cat. No. MM-0047R2) and TNF-α in supernatants were co-assessed in vitro using ELISA.

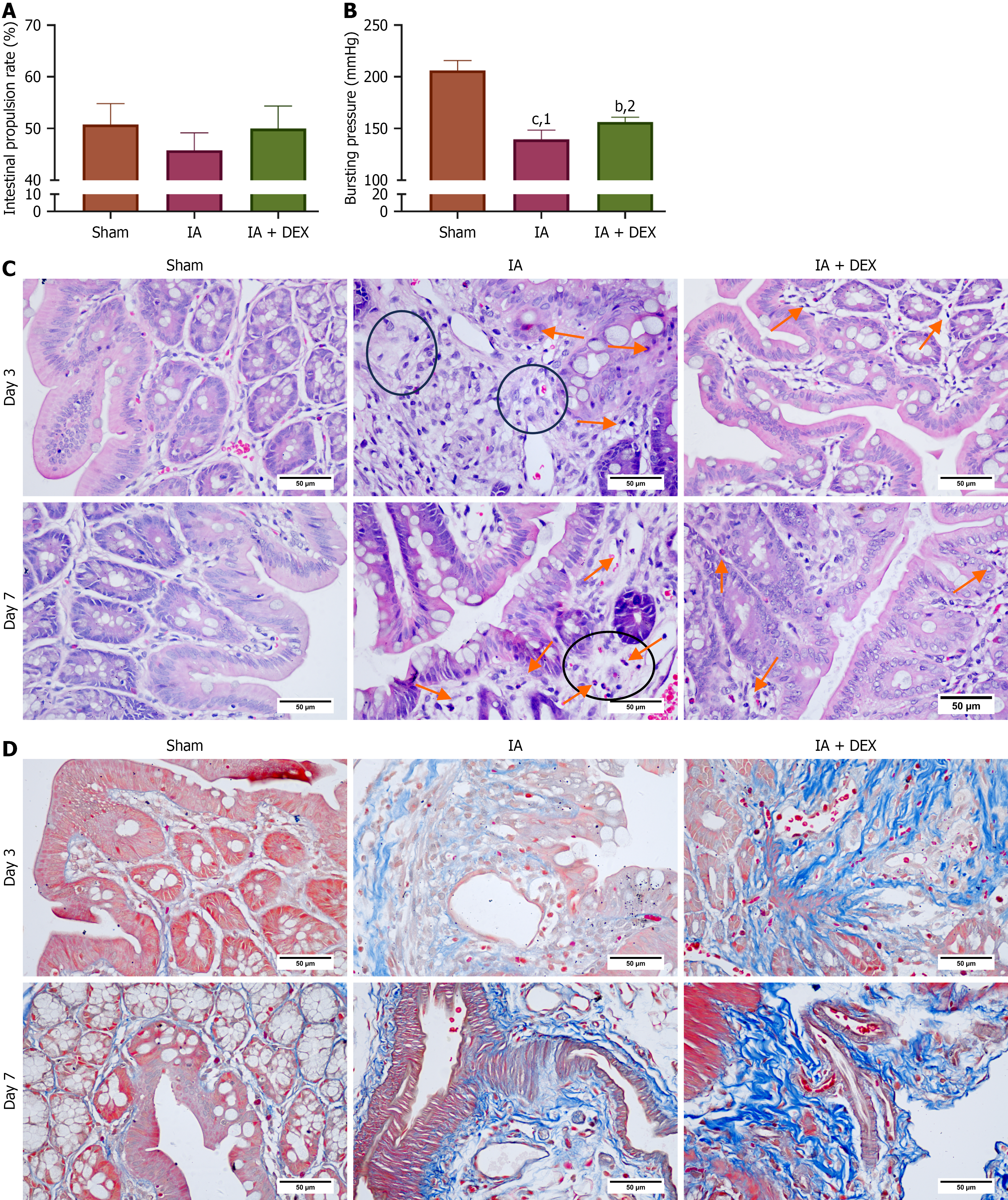

We evaluated anastomotic tissue by hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining. Collagen fibers in anastomotic tissues were assessed via Masson trichrome staining. Serial sections from paraffin blocks were cut using a microtome and stained sequentially with: Hematoxylin, Masson’s bluing agent, Lichtenstein’s red magenta, and aniline blue. After preparing HE staining sections, all specimens were independently evaluated by board-certified pathologists using standardized histological assessment criteria. The histopathological analysis systematically assessed 5 key parameters: (1) Mucosal continuity; (2) Re-epithelialization status; (3) Muscular layer integrity; (4) The density of inflammatory cell infiltration; and (5) Neovascularization. Each histological parameter was graded on a validated ordinal scale, and the summative histologic anastomotic healing score of the anastomotic site was calculated through arithmetic summation of individual component scores.

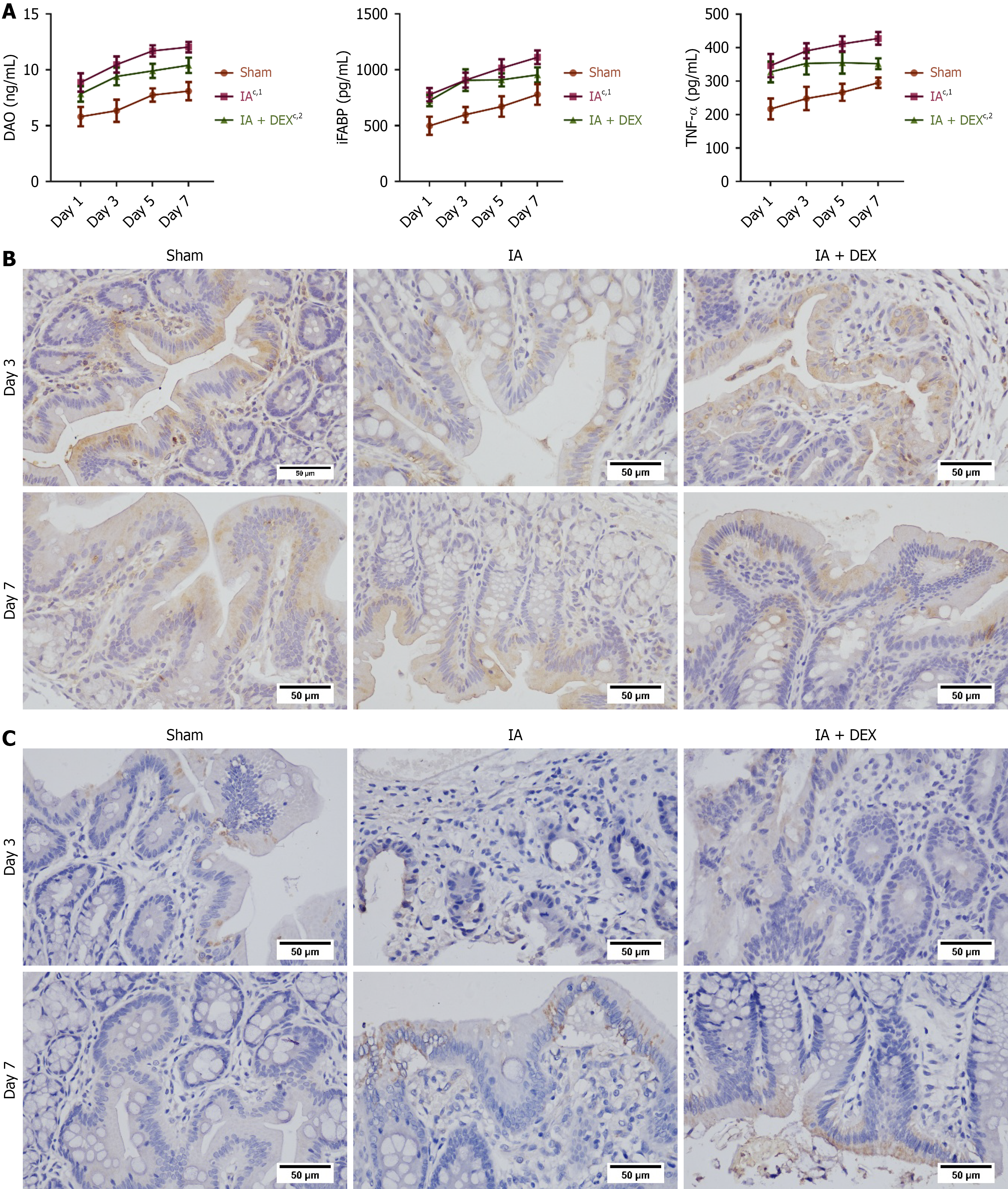

We measured claudin-1 and zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) expression in anastomotic tissues by immunohistochemical staining. Four-micrometer serial paraffin sections were dewaxed with xylene and rehydrated in a graded alcohol series. After quenching endogenous peroxidase with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide (15 minutes) and blocking with 1% bovine serum albumin (30 minutes), the tissue sections underwent overnight incubation at 4 °C with primary antibodies: Anti-claudin-1 (Proteintech, No. 13050-1-AP; 1:50) and anti-ZO-1 (Proteintech, No. 21773-1-AP; 1:1000). The sections were subsequently incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody (Proteintech, No. SA00004-2; 1:500) for 1 hour, followed by 3,3’-diaminobenzidine chromogen development. Nuclear counterstaining was conducted using hematoxylin. Finally, all sections were observed and digitally imaged under a light microscope.

Protein lysates were prepared from rat intestinal tissues and IEC-6 cells with radio immunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer. Total protein concentrations were normalized across groups. Proteins were separated on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Membranes were blocked for 1 hour at ambient temperature using 5% bovine serum albumin in tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with the following primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight: Anti-glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta (GSK-3β) (Proteintech, No. 67558-1-Ig; 1:2000), anti-β-catenin (Proteintech, No. 51067-2-AP; 1:5000), anti-claudin-1 (Proteintech, No. 13050-1-AP; 1:1000), anti-ZO-1 (Proteintech, No. 21773-1-AP; 1:5000), and anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Proteintech, No. 10494-1-AP; 1:20000). Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with a goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Boster, Cat, No. BA1055; 1:5000) at ambient temperature for 2 hours. Finally, an automatic luminescence imaging system (Tanon 5200, Tanon, Shanghai, China) was employed to detect protein expression levels.

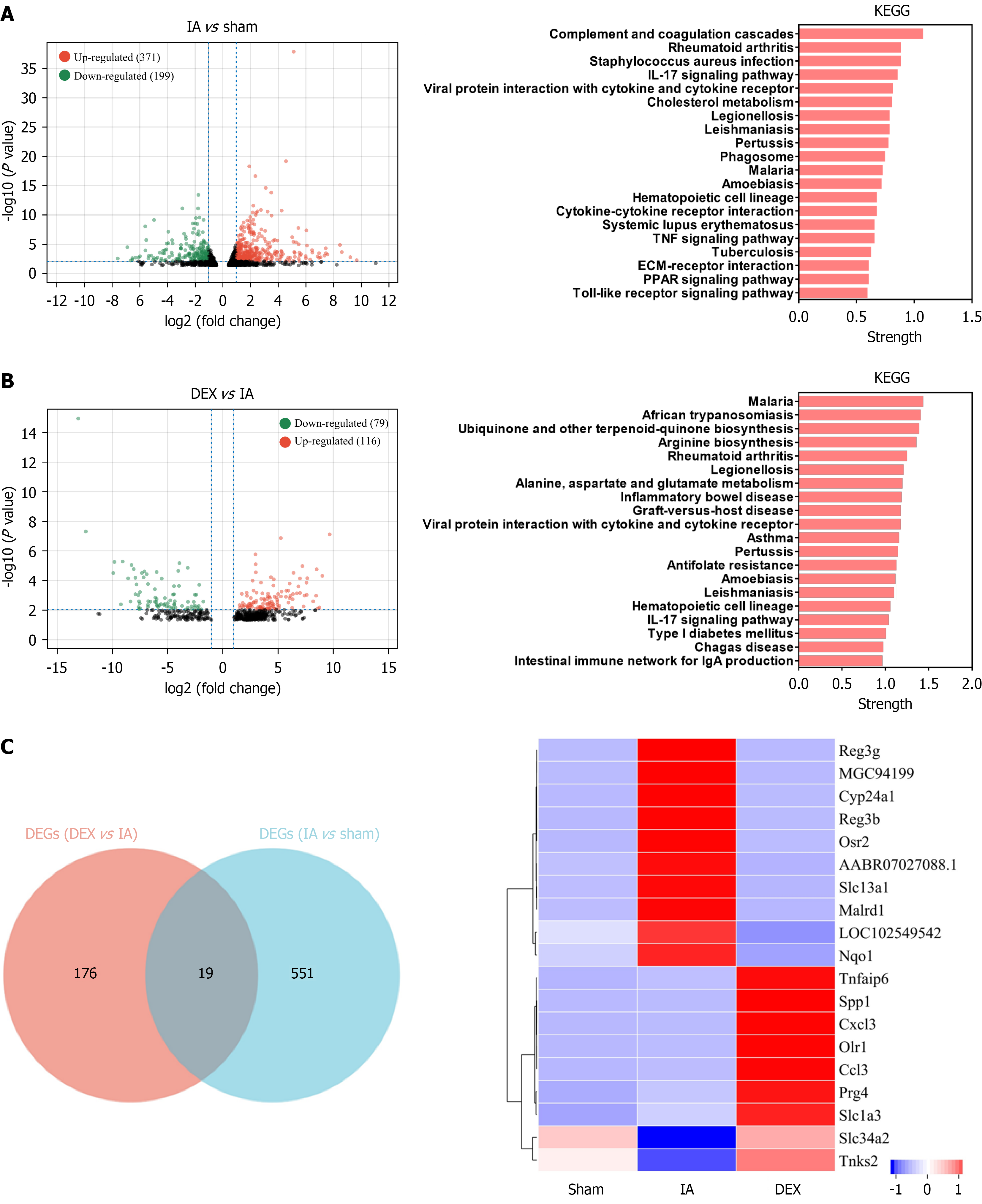

On postoperative day 3, rats were anesthetized, euthanized, and anastomotic tissues were harvested for high-throughput sequencing to investigate the molecular mechanisms of DEX. Raw sequencing data quality was assessed using FastQC (v0.11.9). Trimmomatic (v0.39) was used to trim adapters and low-quality bases. The clean reads were then aligned to the rat reference genome (mRatBN7.2) using HISAT2 (v2.2.1) with default parameters. Gene expression was quantified using featureCounts (v2.0.1). Differential expression analysis was performed using the DESeq2 (v1.30.1) package in R (v4.0.3). Genes with an adjusted P value < 0.01 and an absolute log2 fold change ≥ 1 were identified as differentially expressed. Volcano plots and heatmaps were generated using the ggplot2 package in R. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis for the significant genes was performed with clusterProfiler. Final figures were prepared and arranged using R and GraphPad Prism (v6.01).

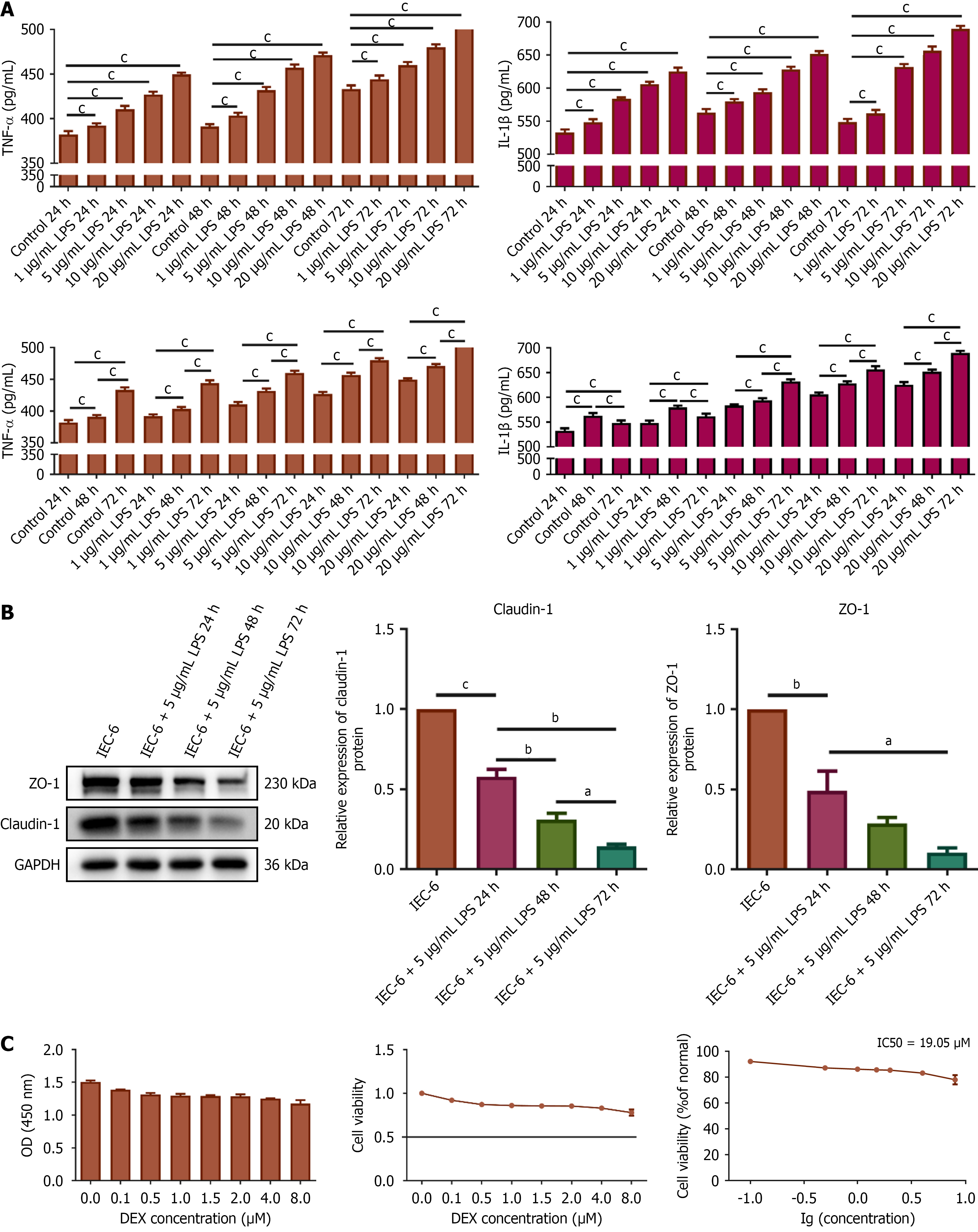

To elucidate the mechanism of action of DEX, a series of in vitro experiments were conducted. The rat intestinal epithelial cell line IEC-6 was obtained from Guangzhou Huiyuanyuan Pharmaceutical Technology Co. Cell cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere using Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin). The cells were treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to mimic intestinal inflammation. A 10 mg/mL stock solution of LPS (L2880, Sigma) was prepared by initially dissolving it in dimethyl sulfoxide, which was subsequently diluted to the desired working concentrations using RPMI 1640 medium prior to each experiment. The cells were treated with 0, 1, 5, 10, and 20 μg/mL LPS to determine the appropriate concentration of LPS. The cells were also treated with LPS for 24 hours, 48 hours, or 72 hours. Subsequently, we measured TNF-α and IL-1β levels in the supernatants of IEC-6 cell cultures using ELISA. Based on these results, the experimental conditions for the cell model were optimized. DEX was diluted directly in RPMI 1640 medium to obtain the required concentrations for experimental use. IEC-6 cells were treated with DEX at concentrations of 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1.5, 2, 4, or 8 μM for 24 hours to determine the cytotoxic effects of DEX. The cell counting kit (CCK)-8 assay (Beyotime, Shanghai, China; Cat No. C0039) was then conducted to select the optimal concentration of DEX for subsequent interventions. In vitro experiments were conducted under the experimental conditions optimized based on the results. To investigate the therapeutic mechanism of DEX, we inhibited the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in IEC-6 cells with dickkopf-1 (DKK-1) (HY-P72978, MedChemExpress). A stock solution of DKK-1 (10 μg/mL) was prepared in double distilled water and diluted to the working concentration in RPMI 1640 medium immediately before cell treatment.

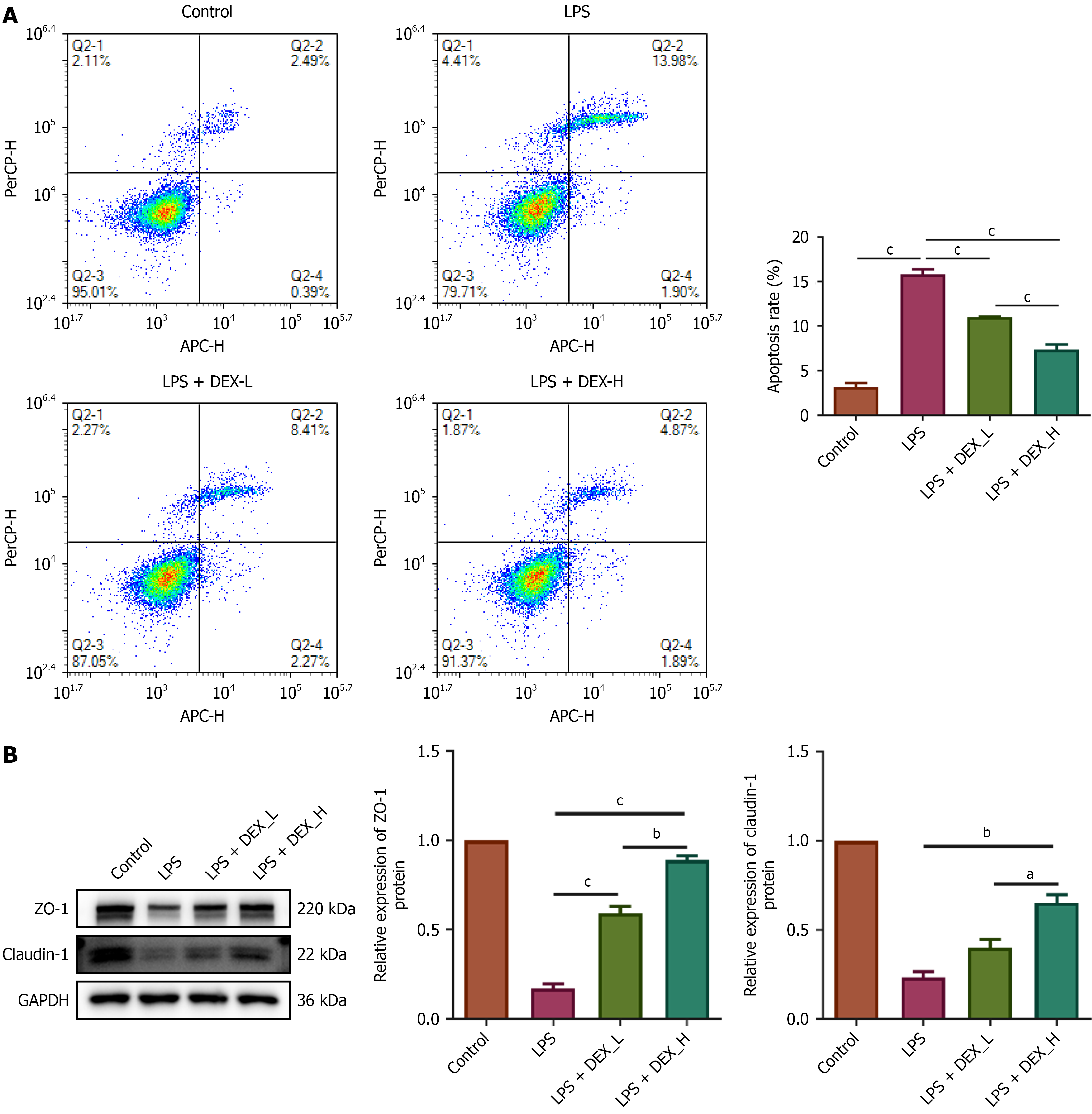

We measured the apoptosis of IEC-6 cells using flow cytometry. The cells were suspended in 500 μL of binding buffer solution. A staining solution (Sigma-Aldrich Cat. No. APOAF-20TST) contained 5 μL each of phycoerythrin and fluo

IEC-6 cells underwent sequential processing: Formaldehyde fixation (4%), permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100, blocking in 5% bovine serum albumin, followed by overnight immunostaining at 4 °C using β-catenin primary antibody (Proteintech, No. 51067-2-AP; 1:200). The samples were then equilibrated to RT for 45 minutes and incubated with a Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (ABclonal, Cat No. AS007, 1:100) in the dark for 40 minutes. Cell nuclei were counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (KeyGEN BioTECH, Jiangsu Province, China; No. KGA215-50) for 2 minutes under light-protected conditions. All slides were imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon AXR NSPARC).

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25.0, with P < 0.05 defining significance. Continuous variables were assessed for normality via Shapiro-Wilk tests (P > 0.05 considered normal), supplemented by quantile-quantile plot inspection. Normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD. The homogeneity of variances was verified using Levene’s test (P > 0.05 considered homogeneous). Independent samples t-tests were applied for two-group comparisons of normally distributed variables. Student’s t-test was used when variances were homogeneous, and Welch’s t-test with Satterthwaite degrees of freedom adjustment was used when variances were heterogeneous. For three or more groups comparisons of normally distributed variables, one-way analysis of variance was employed. Pairwise comparisons were conducted using Tukey’s honestly significant difference test when variances were homogeneous; otherwise, the Games-Howell test was applied for pairwise comparisons. Longitudinal data with normal distribution were analyzed by two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance for the main effects of time and group, as well as the time × group interaction.

Bowel movement is an important indicator of gastrointestinal function recovery. We first investigated the effects of DEX on the postoperative colonic motor function of rats by measuring the intestinal propulsion rate on the 6th postoperative day (Figure 1A). The intestinal propulsion rates of the sham group, IA group, and IA + DEX group were 50.80 ± 4.00, 45.80 ± 3.38, and 50.01 ± 4.36, respectively. A discernible increase in the intestinal propulsion rate was observed in the DEX + IA group, although the difference did not reach statistical significance. Low strength at the anastomotic site is a risk factor for AL. Bursting pressure measurement is a standard method to measure anastomotic strength. We measured anastomotic bursting pressure on postoperative day 7 (Figure 1B). The IA + DEX group showed a significantly higher anastomotic bursting pressure compared to the IA group, suggesting that treatment with DEX can enhance strength at the intestinal anastomotic site.

On the 3rd and 7th days after IA, the intestinal tissues at the anastomosis site were harvested for HE staining. Tissue sections from the IA group exhibited disrupted muscle layer and inflammatory cell infiltration, alongside notable sub

| Time | IA | IA + DEX | P value |

| Day 3 | 7.14 ± 1.23 | 8.79 ± 1.37 | 0.003 |

| Day 7 | 9.07 ± 1.27 | 10.79 ± 1.42 | 0.002 |

We next measured the intestinal barrier function of rats after surgery by detecting the serum level of proteins related to intestinal barrier function, such as DAO and iFABP. DAO and iFABP levels increased gradually from day 1 to day 7 after surgery, indicating intestinal barrier dysfunction (Figure 2A). Relative to sham group, the IA group showed significant increases in serum DAO and iFABP levels. Treatment with DEX downregulated the concentrations of DAO. The protein levels of claudin-1 and ZO-1 at the anastomosis sites was measured using immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2B and C). The IA group demonstrated reduced ZO-1 and claudin-1 expression compared to sham controls, which was reversed by DEX. These findings indicated that DEX improved intestinal barrier function and ameliorated mucosal injury after anastomosis. A significant increase in serum TNF-α was observed in the IA group compared to sham controls. DEX attenuated this increase, demonstrating its capacity to mitigate inflammatory responses after IA (Figure 2A).

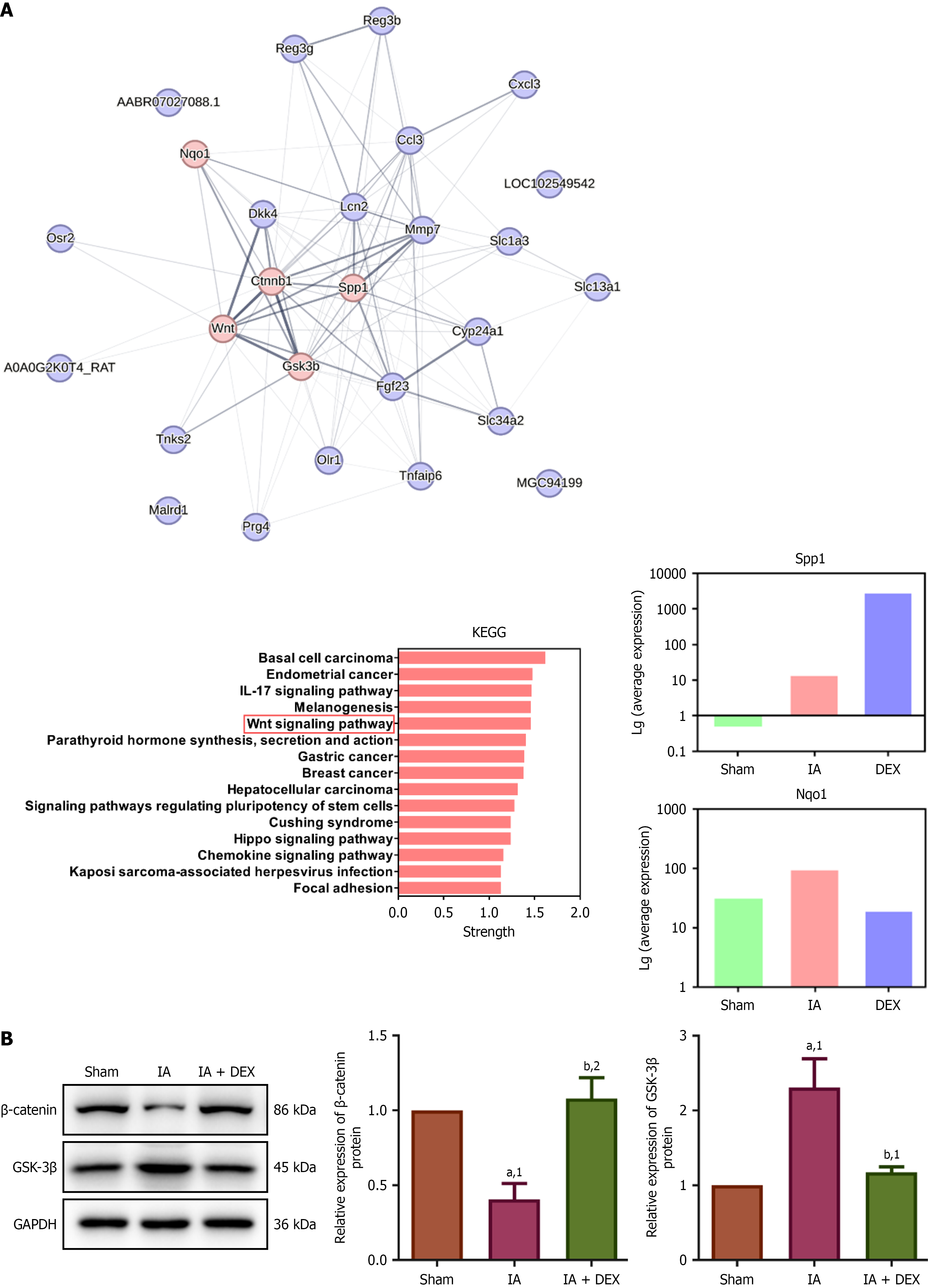

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified through bioinformatics analysis (Figure 3A and B). There were 371 upregulated and 199 downregulated DEGs between the IA group and the sham group. KEGG pathway analysis suggested significant enrichment of the DEGs in key inflammatory signaling pathways, such as the IL-17, TNF, and Toll-like receptor pathways. There were 116 upregulated and 79 downregulated DEGs between the DEX + IA group and the IA group. KEGG enrichment revealed that these DEGs were involved in inflammatory diseases. A comparison of all these DEGs revealed 19 common targets (Figure 3C) that could be associated with the effects of DEX on IA-induced intestinal dysfunction. The Wnt signaling pathway was implicated in the DEX-mediated recovery from IA-induced intestinal dysfunction, based on protein-protein interaction and KEGG analyses of these key genes (Figure 4A).

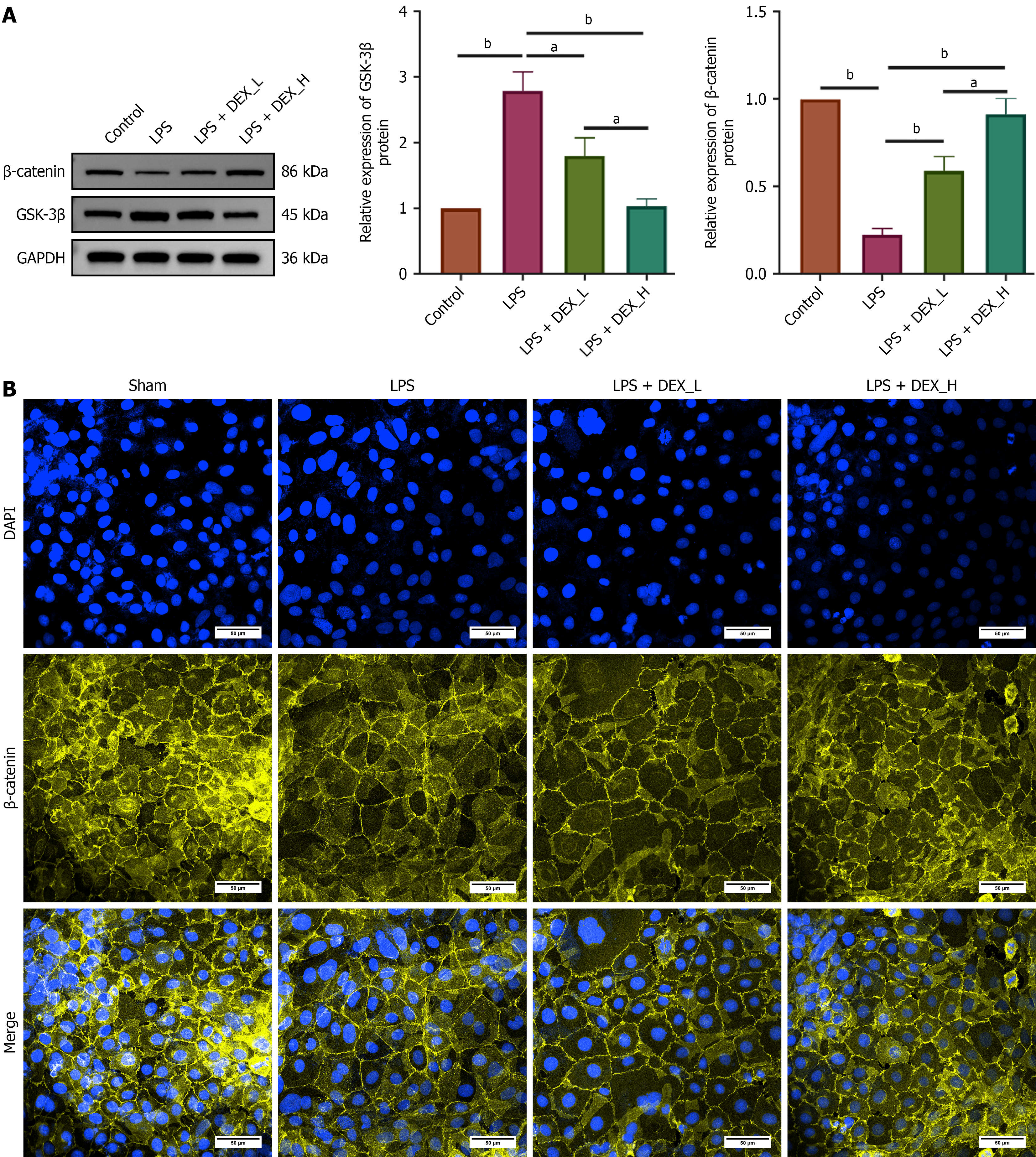

Building on sequencing data, Western blotting (Figure 4B) was conducted to assess Wnt/β-catenin signaling in anastomotic tissues. The IA group exhibited significantly increased GSK-3β expression (P = 0.0167) but decreased β-catenin levels (P = 0.0079) compared to sham controls. Treatment with DEX reversed these changes (vs IA group, GSK-3β: P = 0.0083; β-catenin: P = 0.0142). Our data support a role for the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in mediating the therapeutic effects of DEX on IA-induced intestinal dysfunction.

To elucidate the mechanism of action of DEX, TNF-α and IL-1β release from LPS-stimulated IEC-6 cells were assessed in the culture supernatants after treatment with varying concentrations of DEX. LPS at 5 μg/mL induced the release of TNF-α and IL-1β in a time-dependent manner (Figure 5A). Thus, 5 μg/mL of LPS and 72 hours were selected for subsequent experiments. Western blotting demonstrated time-dependent suppression of claudin-1 and ZO-1 expression in IEC-6 cells by 5 μg/mL LPS (Figure 5B). CCK-8 assay revealed a DEX IC50 (half maximal inhibitory concentration) of 19.05 μM in IEC-6 cells at 24 hours (Figure 5C). Thus, 2.4 μM and 4.8 μM DEX were employed in subsequent experiments. We conducted flow cytometry to investigate whether DEX protects IEC-6 cells exposed to LPS. Flow cytometry indicated that IEC-6 cells pretreated with DEX resisted LPS-induced apoptosis (Figure 6A). We showed that pre-treatment with DEX reversed LPS-induced downregulation of claudin-1 and ZO-1 expression in IEC-6 cells (Figure 6B), suggesting that DEX prevented LPS-induced tight junction dysfunction in intestinal cells.

Western blotting was conducted to assess the modulatory effects of DEX on this pathway in IEC-6 cells. LPS induction significantly upregulated GSK-3β but downregulated β-catenin protein levels. Pretreatment with DEX reversed these LPS-induced alterations in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 7A). Considering that nuclear translocation of β-catenin represents a critical step in activating the Wnt pathway, we examined its subcellular localization via immunofluorescence staining using confocal microscopy. LPS exposure markedly reduced nuclear β-catenin fluorescence intensity, whereas pretreatment with DEX substantially restored the nuclear localization of β-catenin (Figure 7B). Collectively, these findings indicate that DEX exerts therapeutic effects potentially by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

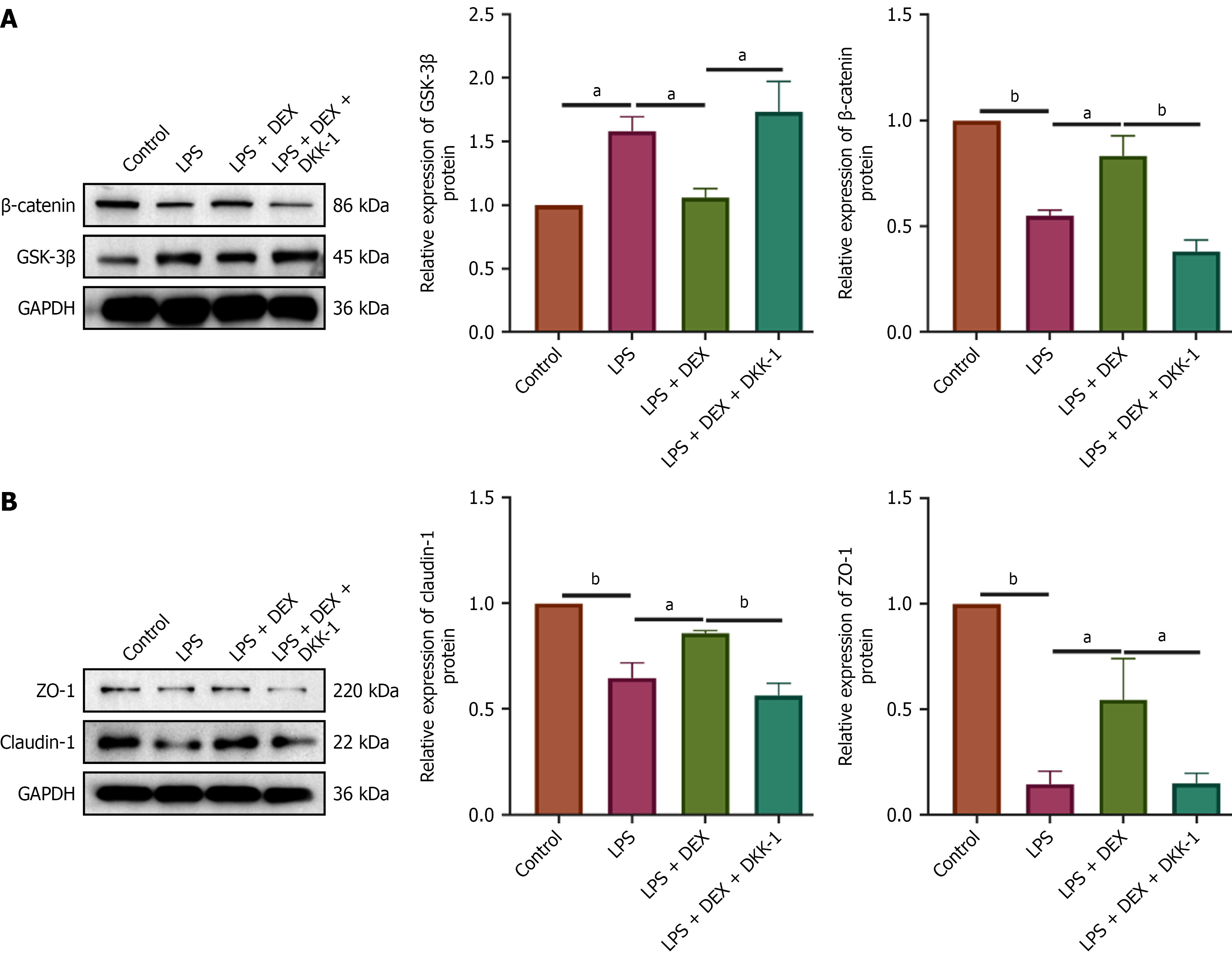

To determine whether the protective effects of DEX are mediated through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, we inhibited the pathway using DKK-1. An inflammatory model was established in IEC-6 cells using 5 μg/mL LPS for 72 hours. Cells were pretreated for 24 hours as follows: The DEX group received 4.8 μM DEX; The DEX + DKK-1 group received both DEX (4.8 μM) and DKK-1 (20 ng/mL). All pretreated cells were then exposed to LPS. Following LPS exposure, protein expression of β-catenin, GSK-3β, claudin-1, and ZO-1 was analyzed by Western blot. As expected, DKK-1 co-treatment effectively blocked DEX-induced activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, as evidenced by a significant downregulation of β-catenin and upregulation of GSK-3β compared to the DEX-only group (Figure 8A). Consistent with the pathway inhibition, the enhancing effects of DEX on the tight junction proteins claudin-1 and ZO-1 were also abolished by DKK-1 co-treatment, which significantly reduced the expression of both proteins (Figure 8B). These results demonstrate that the protective effect of DEX on intestinal barrier integrity, via upregulation of claudin-1 and ZO-1, is dependent on activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

Our study indicated that DEX, a selective α2-adrenergic receptor agonist, accelerates anastomotic healing in a rat model of colorectal surgery by enhancing intestinal barrier function, increasing wall strength, and promoting collagen synthesis. These findings align with clinical evidence showing the ability of DEX to reduce postoperative inflammation and improve gastrointestinal recovery, evidenced by decreased levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and CRP[10]. Histopathological analysis confirmed reduced inflammatory cell infiltration and decreased TNF-α levels, supporting the anti-inflammatory role of DEX in enhancing recovery. This makes DEX a potential therapeutic agent for mitigating postoperative complications.

Decreased intestinal barrier function is associated with poor postoperative intestinal healing[16-18]. DAO mainly exists in the intestinal mucosa and proximal renal tubule cells. The serum level of DAO increases when the intestinal barrier is damaged[19-21]. iFABP is a protein produced by intestinal cells and maintains the integrity of the intestinal epithelium[22,23]. We found that DEX decreased the serum levels of DAO and iFABP, two biomarkers of intestinal barrier dysfunction[24] Furthermore, DEX restored ZO-1 and claudin-1 expression at the anastomosis site, indicating its ability to maintain intestinal epithelial integrity. Interestingly, we found that IA suppressed the expression of β-catenin, which was reversed by DEX. Miwa et al[25] reported that downregulation of intracellular β-catenin can decrease the expression of CLDN1 in colon cancer cells[25]. Whether IA-induced decrease in β-catenin expression downregulates CLDN1 expression in colon epithelial cells deserves further studies. Nevertheless, we hypothesized that DEX may increase CLDN1 expression by enhancing β-catenin expression.

In vitro experiments using IEC-6 cells also validated the protective effects of DEX. Pretreatment with DEX not only prevented LPS-induced downregulation of tight junction proteins but also inhibited the apoptosis of IEC-6 cells. Our results align with the findings of other researchers, where pretreatment with DEX prevented LPS-induced downregulation of ZO-1 and claudin-1 in burn-induced intestinal dysfunction[26]. Similarly, Xia et al[27] reported that DEX can decrease intestinal permeability and sustain the integrity of the intestinal barrier in a rat heatstroke model by suppressing apoptosis and augmenting the levels of tight junction proteins (occludin, ZO-1). The results are also consistent with the clinical studies reporting that DEX can improve intestinal barrier integrity in patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery[28]. The preservation of tight junction proteins is critical for maintaining barrier function and preventing postoperative complications, such as sepsis. These findings highlight the direct cytoprotective and anti-apoptotic effects of DEX on intestinal epithelial cells.

Notably, this study further elucidates a key molecular mechanism through which DEX exerts its protective effects. We found that DEX activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, as evidenced by increased β-catenin expression and decreased GSK-3β expression. More importantly, when the pathway was blocked using the specific inhibitor DKK-1, the up-regulatory effects of DEX on the tight junction proteins claudin-1 and ZO-1 were significantly reversed. This result directly demonstrates that DEX maintains intestinal epithelial barrier integrity by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, providing a novel mechanistic explanation for the therapeutic effects of DEX. Our results align with previous studies highlighting the central role of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in regulating tight junction protein expression and epithelial barrier function[29-32].

Our findings align with emerging evidence on DEX’s multifaceted role in postoperative recovery. For instance, Ye et al[33] reported that DEX mitigates intestinal inflammation in ulcerative colitis models by suppressing the Toll-like receptor 4/MyD88/nuclear factor kappa-B pathway, complementing our observation of reduced TNF-α levels. Similarly, a meta-analysis by Sharma et al[34] confirmed that DEX enhances postoperative gastrointestinal recovery in colorectal surgery patients, consistent with our observed increase in anastomotic burst pressure and propulsion rate. Additionally, He et al[35] reported that an extra loading dose of DEX improves intestinal function recovery post-colorectal resection, supporting our findings on barrier function preservation via upregulation of claudin-1 and ZO-1. Furthermore, Xu et al[36] highlighted DEX’s ability to attenuate systemic inflammation in digestive tract cancer surgery, aligning with our results on reduced serum TNF-α. These studies collectively underscore DEX’s potential as a perioperative adjuvant to mitigate complications such as AL.

Despite providing valuable insights, this study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the use of a rodent model limits the direct translation of our findings to humans, due to known differences in immune responses and gut microbiota composition between rodents and humans. Although we supplemented in vitro experiments with key mechanistic evidence, further in vivo studies involving direct intervention in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in animal models are necessary to validate its indispensability. Third, the long-term effects of DEX on healing outcomes, such as scar formation and sustained functional recovery, were not evaluated; these aspects are critical for clinical application and warrant future investigation. Finally, while pharmacological inhibition with DKK-1 supports the involvement of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in DEX’s effects, further validation using complementary approaches, such as genetic knockdown of β-catenin, will help to more definitively establish this mechanistic link.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that DEX promotes anastomotic healing by attenuating inflammation and preserving intestinal barrier integrity. Furthermore, in vitro experiments reveal that DEX protects the intestinal barrier by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway to upregulate claudin-1 and ZO-1. These findings suggest that DEX may improve postoperative recovery and reduce complications in patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Further randomized controlled trials are warranted to validate these findings and quantify the clinical benefits of DEX in perioperative management. Moreover, therapeutic strategies targeting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway may offer novel avenues for promoting postoperative intestinal healing.

We thank Fujian Province Natural Science Foundation and Longyan City Science and Technology Plan Project for supporting the research.

| 1. | Frouws MA, Snijders HS, Malm SH, Liefers GJ, Van de Velde CJH, Neijenhuis PA, Kroon HM. Clinical Relevance of a Grading System for Anastomotic Leakage After Low Anterior Resection: Analysis From a National Cohort Database. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:706-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tevis SE, Kennedy GD. Postoperative Complications: Looking Forward to a Safer Future. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2016;29:246-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Buchs NC, Gervaz P, Secic M, Bucher P, Mugnier-Konrad B, Morel P. Incidence, consequences, and risk factors for anastomotic dehiscence after colorectal surgery: a prospective monocentric study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:265-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Veyrie N, Ata T, Muscari F, Couchard AC, Msika S, Hay JM, Fingerhut A, Dziri C; French Associations for Surgical Research. Anastomotic leakage after elective right versus left colectomy for cancer: prevalence and independent risk factors. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:785-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Arcangeli A, D'Alò C, Gaspari R. Dexmedetomidine use in general anaesthesia. Curr Drug Targets. 2009;10:687-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tanskanen PE, Kyttä JV, Randell TT, Aantaa RE. Dexmedetomidine as an anaesthetic adjuvant in patients undergoing intracranial tumour surgery: a double-blind, randomized and placebo-controlled study. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:658-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li M, Wang T, Xiao W, Zhao L, Yao D. Low-Dose Dexmedetomidine Accelerates Gastrointestinal Function Recovery in Patients Undergoing Lumbar Spinal Fusion. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen C, Huang P, Lai L, Luo C, Ge M, Hei Z, Zhu Q, Zhou S. Dexmedetomidine improves gastrointestinal motility after laparoscopic resection of colorectal cancer: A randomized clinical trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e4295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pan W, Liu G, Li T, Sun Q, Jiang M, Liu G, Ma J, Liu H. Dexmedetomidine combined with ropivacaine in ultrasound-guided tranversus abdominis plane block improves postoperative analgesia and recovery following laparoscopic colectomy. Exp Ther Med. 2020;19:2535-2542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang K, Wu M, Xu J, Wu C, Zhang B, Wang G, Ma D. Effects of dexmedetomidine on perioperative stress, inflammation, and immune function: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123:777-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lu Y, Fang PP, Yu YQ, Cheng XQ, Feng XM, Wong GTC, Maze M, Liu XS; POGF Study Collaborators. Effect of Intraoperative Dexmedetomidine on Recovery of Gastrointestinal Function After Abdominal Surgery in Older Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2128886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Li B, Lee C, Cadete M, Zhu H, Koike Y, Hock A, Wu RY, Botts SR, Minich A, Alganabi M, Chi L, Zani-Ruttenstock E, Miyake H, Chen Y, Mutanen A, Ngan B, Johnson-Henry KC, De Coppi P, Eaton S, Määttänen P, Delgado-Olguin P, Sherman PM, Zani A, Pierro A. Impaired Wnt/β-catenin pathway leads to dysfunction of intestinal regeneration during necrotizing enterocolitis. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Miyoshi H, Ajima R, Luo CT, Yamaguchi TP, Stappenbeck TS. Wnt5a potentiates TGF-β signaling to promote colonic crypt regeneration after tissue injury. Science. 2012;338:108-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 396] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | McCarthy CK, McGaha PK, Rozich NS, Yokell NA, Lees JS, Berry WL. Creation of Colonic Anastomosis in Mice. J Vis Exp. 2019;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kitajima Y, Hashizume NS, Saiki C, Ide R, Imai T. Effect of dexmedetomidine on cardiorespiratory regulation in spontaneously breathing adult rats. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0262263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hajjar R, Gonzalez E, Fragoso G, Oliero M, Alaoui AA, Calvé A, Vennin Rendos H, Djediai S, Cuisiniere T, Laplante P, Gerkins C, Ajayi AS, Diop K, Taleb N, Thérien S, Schampaert F, Alratrout H, Dagbert F, Loungnarath R, Sebajang H, Schwenter F, Wassef R, Ratelle R, Debroux E, Cailhier JF, Routy B, Annabi B, Brereton NJB, Richard C, Santos MM. Gut microbiota influence anastomotic healing in colorectal cancer surgery through modulation of mucosal proinflammatory cytokines. Gut. 2023;72:1143-1154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 17. | Hajjar R, Fragoso G, Oliero M, Alaoui AA, Calvé A, Vennin Rendos H, Cuisiniere T, Taleb N, Thérien S, Dagbert F, Loungnarath R, Sebajang H, Schwenter F, Wassef R, Ratelle R, Debroux E, Richard C, Santos MM. Basal levels of microbiota-driven subclinical inflammation are associated with anastomotic leak in patients with colorectal cancer. Gut. 2024;73:1031-1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hajjar R, Richard C, Santos MM. The gut barrier as a gatekeeper in colorectal cancer treatment. Oncotarget. 2024;15:562-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Camilleri M. Leaky gut: mechanisms, measurement and clinical implications in humans. Gut. 2019;68:1516-1526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 352] [Cited by in RCA: 751] [Article Influence: 107.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kamei H, Hachisuka T, Nakao M, Takagi K. Quick recovery of serum diamine oxidase activity in patients undergoing total gastrectomy by oral enteral nutrition. Am J Surg. 2005;189:38-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ma M, Zheng Z, Zeng Z, Li J, Ye X, Kang W. Perioperative Enteral Immunonutrition Support for the Immune Function and Intestinal Mucosal Barrier in Gastric Cancer Patients Undergoing Gastrectomy: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Study. Nutrients. 2023;15:4566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Timmermans K, Sir Ö, Kox M, Vaneker M, de Jong C, Gerretsen J, Edwards M, Scheffer GJ, Pickkers P. Circulating iFABP Levels as a marker of intestinal damage in trauma patients. Shock. 2015;43:117-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yuan JH, Xie QS, Chen GC, Huang CL, Yu T, Chen QK, Li JY. Impaired intestinal barrier function in type 2 diabetic patients measured by serum LPS, Zonulin, and IFABP. J Diabetes Complications. 2021;35:107766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kong C, Li SM, Yang H, Xiao WD, Cen YY, Wu Y, Li WM, Sun DL, Xu PY. Screening and combining serum biomarkers to improve their diagnostic performance in the detection of intestinal barrier dysfunction in patients after major abdominal surgery. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Miwa N, Furuse M, Tsukita S, Niikawa N, Nakamura Y, Furukawa Y. Involvement of claudin-1 in the beta-catenin/Tcf signaling pathway and its frequent upregulation in human colorectal cancers. Oncol Res. 2001;12:469-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Qin C, Jiang Y, Chen X, Bian Y, Wang Y, Xie K, Yu Y. Dexmedetomidine protects against burn-induced intestinal barrier injury via the MLCK/p-MLC signalling pathway. Burns. 2021;47:1576-1585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Xia ZN, Zong Y, Zhang ZT, Chen JK, Ma XJ, Liu YG, Zhao LJ, Lu GC. Dexmedetomidine Protects Against Multi-Organ Dysfunction Induced by Heatstroke via Sustaining The Intestinal Integrity. Shock. 2017;48:260-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Qi YP, Ma WJ, Cao YY, Chen Q, Xu QC, Xiao S, Lu WH, Wang Z. Effect of Dexmedetomidine on Intestinal Barrier in Patients Undergoing Gastrointestinal Surgery-A Single-Center Randomized Clinical Trial. J Surg Res. 2022;277:181-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chen XY, Wan SF, Yao NN, Lin ZJ, Mao YG, Yu XH, Wang YZ. Inhibition of the immunoproteasome LMP2 ameliorates ischemia/hypoxia-induced blood-brain barrier injury through the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway. Mil Med Res. 2021;8:62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Duan Y, Huang J, Sun M, Jiang Y, Wang S, Wang L, Yu N, Peng D, Wang Y, Chen W, Zhang Y. Poria cocos polysaccharide improves intestinal barrier function and maintains intestinal homeostasis in mice. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;249:125953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Zhao Y, Chen C, Xiao X, Fang L, Cheng X, Chang Y, Peng F, Wang J, Shen S, Wu S, Huang Y, Cai W, Zhou L, Qiu W. Teriflunomide Promotes Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity by Upregulating Claudin-1 via the Wnt/β-catenin Signaling Pathway in Multiple Sclerosis. Mol Neurobiol. 2024;61:1936-1952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yang K, Zhu J, Wu J, Zhong Y, Shen X, Petrov B, Cai W. Maternal Vitamin D Deficiency Increases Intestinal Permeability and Programs Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway in BALB/C Mice. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2021;45:102-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ye X, Xu H, Xu Y. Dexmedetomidine alleviates intestinal barrier dysfunction and inflammatory response in mice via suppressing TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling in an experimental model of ulcerative colitis. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2022;60:311-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sharma S, Khamar J, Petropolous JA, Ghuman A. Postoperative recovery of colorectal patients enhanced with dexmedetomidine (PReCEDex): a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2024;38:5935-5947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | He GZ, Bu N, Li YJ, Gao Y, Wang G, Kong ZD, Zhao M, Zhang SS, Gao W. Extra Loading Dose of Dexmedetomidine Enhances Intestinal Function Recovery After Colorectal Resection: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:806950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Xu W, Zheng Y, Suo Z, Fei K, Wang Y, Liu C, Li S, Zhang M, Zhang Y, Zheng Z, Ni C, Zheng H. Effect of dexmedetomidine on postoperative systemic inflammation and recovery in patients undergoing digest tract cancer surgery: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Oncol. 2022;12:970557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/