Published online Oct 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i30.9228

Peer-review started: May 26, 2021

First decision: July 15, 2021

Revised: July 17, 2021

Accepted: September 8, 2021

Article in press: September 8, 2021

Published online: October 26, 2021

Processing time: 147 Days and 21.1 Hours

Monteggia and equivalent lesions are relatively rare but result in severe injuries in childhood, typically affecting children between 4 and 10 years old. The diagnosis and treatment of an equivalent Monteggia lesion is more complicated than those of a typical Monteggia fracture. This type of lesion may be challenging and may lead to serious complications if not treated properly. Pediatric Monteggia equivalent type I lesions have been reported in a few reports, all of which the patients were all over 4 years old.

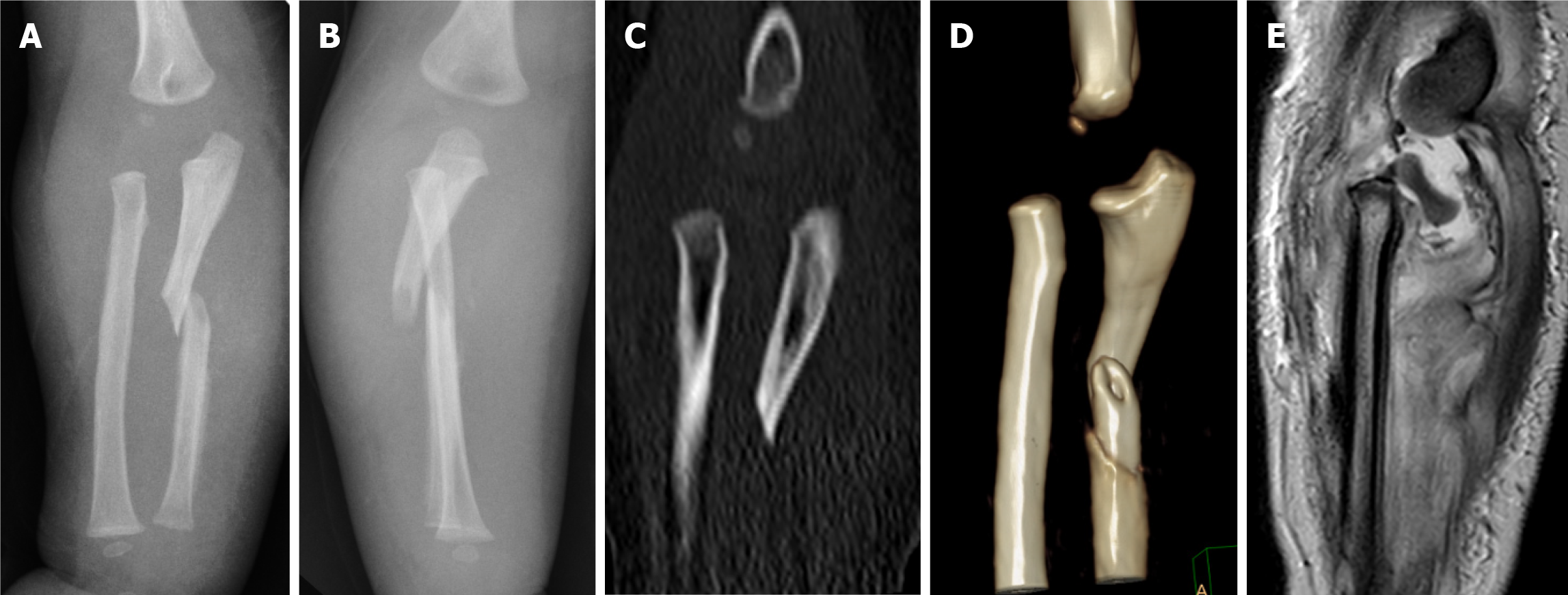

A 14-mo-old boy was referred to our clinic after falling from his bed 10 d prior. With regard to the clinical examination, an obvious swollen and angular deformity was noted on his right forearm. Plain radiographs and reconstructed computed tomography scans showed a Monteggia type I fracture and dislocation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed a type I Monteggia equivalent lesion consisting of ulnar fracture and Salter-Harris type I injury in the proximal radius. The radial head was still in the joint, and only the radial metaphysis was displaced anteriorly. Open reduction and pinning of both displaced radial and ulnar fractures achieved an excellent result with full function.

We recommend MRI examination or arthrography during reduction, especially if the secondary ossification center has not appeared.

Core Tip: We reviewed a case of Monteggia type I equivalent fracture in a 14-mo-old child. This is the youngest patient to suffer from this injury. For patients aged less than 5 years, plain radiograph and reconstructed computed tomography scans cannot distinguish Monteggia fractures and Monteggia equivalent fractures in patients with unossified radial heads. As a result, fractures may be misdiagnosed or neglected, leading to poor clinical and radiographic results. Therefore, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be routinely performed. We recommended MRI examination or arthrography during reduction if cartilage fracture is suspected, especially if the secondary ossification center has not appeared.

- Citation: Li ML, Zhou WZ, Li LY, Li QW. Monteggia type-I equivalent fracture in a fourteen-month-old child: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(30): 9228-9235

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i30/9228.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i30.9228

Monteggia fracture-dislocation is characterized by a simultaneous ulnar fracture and radial head dislocation. Such an injury is relatively rare and represents less than 5% of upper extremity fractures[1-3]. However, this type of lesion may be challenging and lead to serious complications if not treated properly[4]. Moreover, Monteggia lesions are commonly observed in children between 4 and 10 years old[1]. This injury was delineated first by Monteggia in 1814. Based on the direction of radial head dislocation, the Bado classification is widely accepted[4]. In addition, Bado further classified certain injuries as equivalents or variants to Monteggia lesions because of their similar radiographic pattern and biomechanism of injury. Relevant lesions can be identified on equivalent Monteggia lesions, such as olecranon fractures or radial neck or head fractures. The diagnosis and treatment of an equivalent Monteggia lesion is more complicated than those of a typical Monteggia fracture. Among them, fractures of the proximal ulna with radial neck fractures are the most common type I equivalent Monteggia fractures.

We report an unusual case of a Monteggia type I equivalent fracture associated with a fracture of the proximal 1/3 of the ulnar shaft and a Salter-Harris type I injury in the proximal radius in a 14-mo-old boy. The ossified center of the radial head was invisible on radiography for a child of this age, making this injury easy to misdiagnose and neglect.

A 14-mo-old boy was referred to our clinic after falling from his bed 10 d prior.

Pain and swelling of the right elbow and forearm occurred immediately after falling. Rather than going to the hospital, the patient applied a traditional Chinese medicine herbal ointment of unknown composition. Due to the lack of improvement in the right elbow and forearm, an X-ray was performed at a local clinic 9 d after the fall and showed fracture of his right ulnar. Then, he was subsequently transferred to our hospital.

The patient had no previous medical history.

The patient denied any family history and had no notable past history.

An obvious swollen and angular deformity was noted on his right forearm. There was no neurovascular compromise in the extremity.

Laboratory data were unremarkable except for a decreased hemoglobin level at 9.8 g/dL. Electrocardiography was performed, and there was no sign of cardiac injury.

Anteroposterior and lateral views of the affected forearm revealed a short oblique fracture of the ulnar shaft and misalignment between the metaphysis of the proximal radius and the capitellum of the humerus (Figure 1A and B). Reconstructed computed tomography (CT) scans showed an anteriorly displaced radial metaphysis (Figure 1C and D). The child was initially diagnosed with a Monteggia type I fracture and dislocation. However, he had not yet developed an ossification center at the radial head, and the secondary ossification center of the proximal radius was still invisible. Considering the possibility of a cartilaginous radial head injury, an magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan was performed. Interestingly, MRI confirmed a Salter-Harris type I fracture of the radial head epiphysis (Figure 1E). The radial head was still in the joint, and only the radial metaphysis was displaced anteriorly.

According to Bado’s classification, a diagnosis of a Monteggia type I equivalent fracture was made; however, the injury mimicked the classic Monteggia type I fracture.

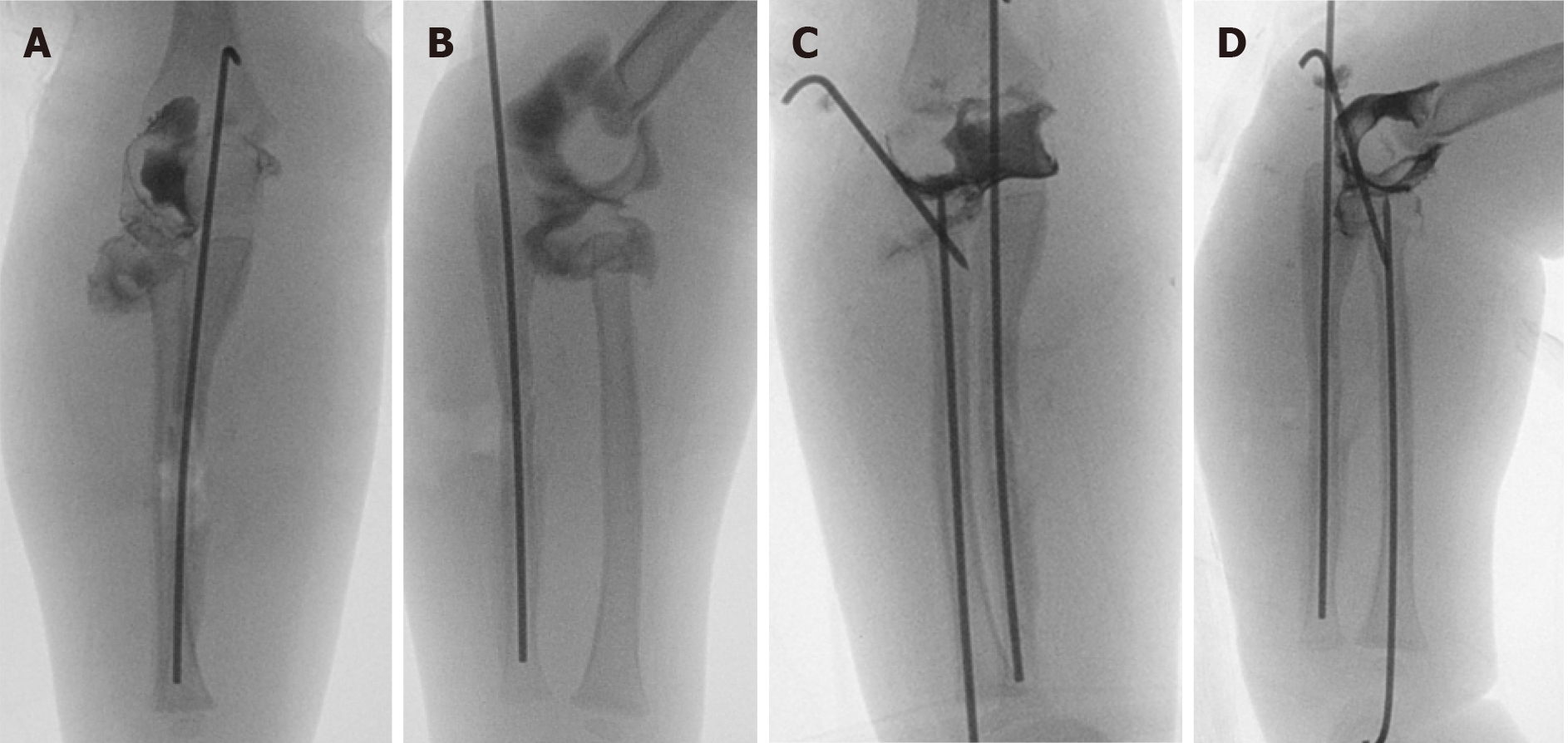

The fracture was manipulated under general anesthesia, but reduction of the ulna failed because of callus formation. Therefore, open reduction was performed, and the ulna was fixed with an intramedullary 1.5 mm Kirshner (k)-wire. Additionally, an arthrogram of the elbow joint was performed, revealing that the radial neck fracture and the radial head were tilted in the elbow joint (Figure 2A and B).

Therefore, we further chose a posterior oblique approach for the radial head, and the annular ligament was intact. After confirming the physeal injury to the proximal radius (Salter-Harris I), the fracture was reduced under direct vision, and a 1.5 mm percutaneous k-wire was used to stabilize the radial head. However, the fracture was unstable during range-of-motion testing; thus, a 2 mm intramedullary k-wire was inserted percutaneously to stabilize the fracture.

Intraoperative arthrogram images revealed a satisfactory reduction of the radial head and stable reduction for ulnar fracture (Figure 2C and D). Then, a long-arm cast was applied. The patient was immobilized for 6 wk postoperatively. The long-arm cast and K-wire were both removed 6 wk after the operation.

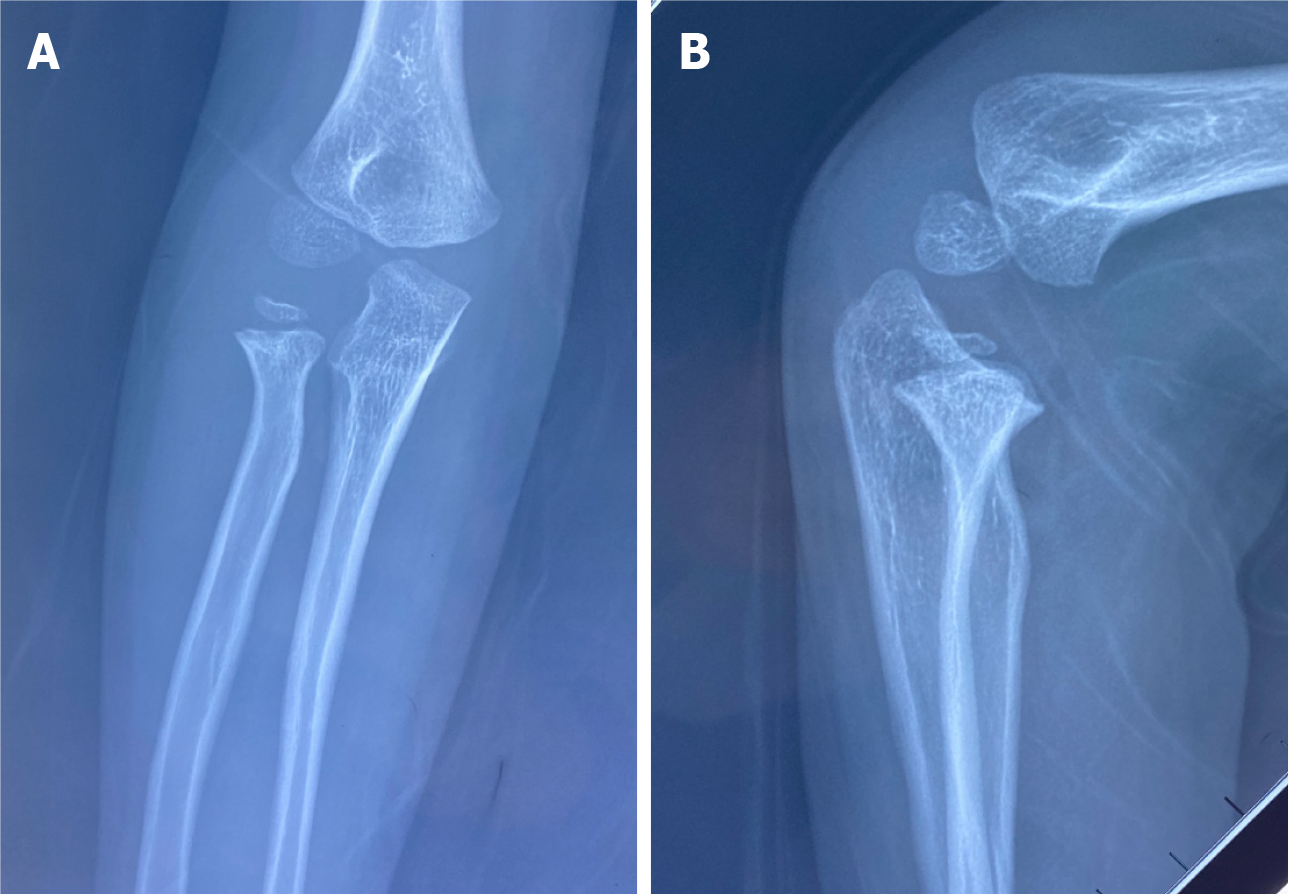

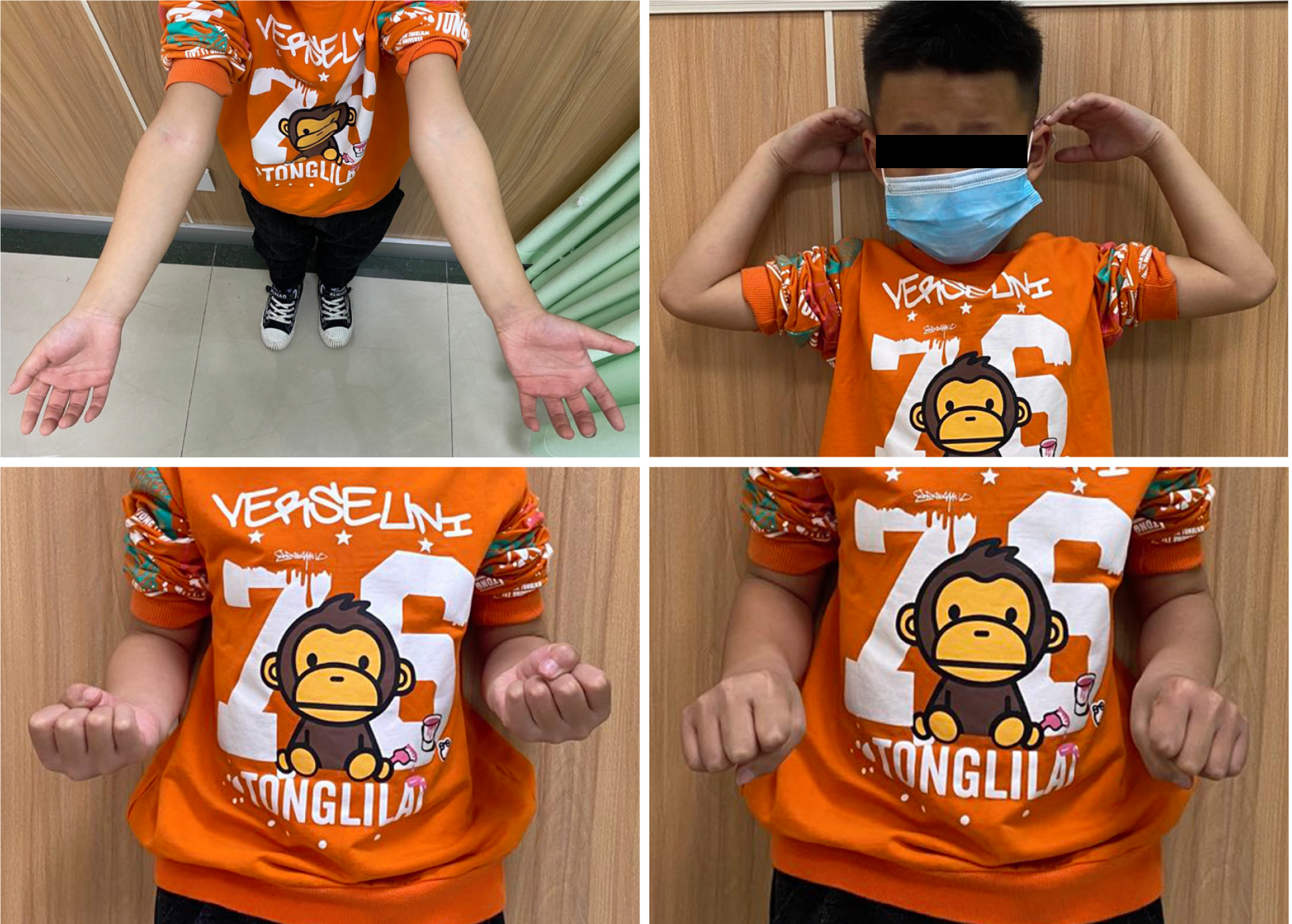

At the five-year follow-up, radiographs revealed the successful union of both bones. The radial head was ossified without secondary necrosis or growth arrest of the proximal radial physis (Figure 3). No limitation of elbow flexion and extension or forearm pronation and supination was observed (Figure 4).

Giovanni Batista Monteggia (1814) first described the fracture of the proximal third of the ulna and an anterior dislocation of the radial head. Bado[5] proposed a classification system based on the direction of radial head dislocation. Bado[5] also described certain injuries of similar radiographic patterns, mechanisms of injuries, or methods of treatment as Monteggia equivalent lesions, in which associated fractures of the radial neck were included[5].

In a retrospective study by Olney and Menelaus[6], out of 102 children with acute Monteggia lesions, type I equivalent lesions were the third most common lesion in acute Monteggia lesions following classic type I and type III Monteggia lesions, suggesting that Monteggia variants may be more common than previously thought. Type I equivalent lesions constitute 59% of Monteggia equivalent lesions in the literature[7], and lesions involving the proximal radius accounted for 14% among acute Monteggia lesions and are the most common type I equivalent Monteggia fractures[6]. However, this lesion has been reported in only a few studies in the English literature, mainly case reports, in which the patients were all over 4 years old[8-13]. A summary of published case reports of pediatric Monteggia type-I equivalent lesions involving proximal radial fracture is illustrated in Table 1.

| Ref. | Age of patient | Position of ulnar fracture | Type of proximal radius fracture | Visibility of radial head ossified | Imaging | Treatment |

| Soin et al[8], 1995 | 6 years | Middle third | Transverse fracture through the neck of the radius | Yes | AP and lateral radiographs | Closed reduction of both ulna and radius |

| Zrig et al[9], 2011 | 6 years | Junction of the proximal and middle third | Transverse fracture through the neck of the radius | Yes | AP and lateral radiographs | Clothed reduction of both ulna and radius |

| Drosos et al[11], 2012 | 6 years | Proximal third | SH-I | Yes | AP and lateral radiographs | Closed reduction and pinning of both ulna and radius |

| Faundez et al[10], 2003 | 6 years | Junction of the proximal and middle third | Transverse fracture through the neck of the radius | Yes | AP and lateral radiographs | Closed reduction and pinning of both ulna and radius |

| Clark et al[12], 2017 | 5 years | Proximal third | Comminuted fracture of radial head and neck | No | AP and lateral radiographs and CT | Closed reduction and pinning of ulna. Open reduction and pinning of radial head |

| ElKhouly et al[13], 2018 | 10 years | Proximal third | SH Type II | Yes | AP and lateral radiographs | Closed reduction of both ulna and radius, nailing of ulnar fracture |

| The present case | 1 year | Middle third | SH-I | No | AP and lateral radiographs, CT and MRI | Open reduction of both ulna and radius |

Even though Monteggia type I equivalent lesions involving ulnar fracture associated with an anteriorly displaced fracture of the neck of the radius in 6-year-old children have been previously reported by Soin et al[8], Zrig et al[9] and Faundez et al[10], the radial head remained in normal alignment to the capitellum, and there was no growth plate involvement.

However, fracture through the growth plate is more likely to occur than radial head dislocation in skeletally immature patients[4]. Thus, Drosos et al[11] illustrated a variant associated with Salter-Harris (SH) type I injury of the radial head in a 6-year-old girl with an ossified radial head, and plain radiographs allowed both assessment and control of reduction. Reina et al[14] described another variant accompanied by a diaphyseal ulnar fracture and a proximal physeal injury with a posteriorly displaced proximal radius in a 13-year-old adolescent. They pointed out that a good diagnosis was necessary, and surgeons should be aware of initial radiographs and should look for associated lesions such as SH type I injury of the radial head.

Nonetheless, it is generally accepted that the ossification center of the radial head is visible at 5 years of age[15]. For patients aged less than 5 years of age, visualization of the anatomy of the fracture is difficult because of the absence of a secondary ossification center of the radial head. As a result, fractures may be misdiagnosed or neglected. Due to the gradual emergence of secondary ossification centers around the elbow, missing diagnoses and misdiagnoses of pediatric elbow injuries are not infrequent[16]. Hence, occult fractures involving an unossified radial head can be completely invisible at the initial evaluation except for disruptions in the surrounding soft tissue planes[17]. Clark et al[12] reported a Monteggia equivalent lesion with a comminuted radial head and neck fractures in a 5-year-old child. Only a small radiodense fleck of metaphyseal bone was noted because of the lack of ossification centers of the radial head in this child and the difficulty in visualizing the radial head even in intraoperative arthrogram, and the radial fracture could not be reduced after multiple attempts. Then, the patient underwent a CT scan of the elbow for evaluation. The radial head and neck were found to be both comminuted fractures, and open reduction of the radial head and neck was conducted. The author advised that surgeons should not hesitate to order a CT scan to diagnosis accurately and aid guidance of correct fixation that cannot be explained by plain films[12]. In addition, arthrography also provides a clear definition of the lesion, allowing both assessment and control of operative reduction, and was utilized in a case with a child younger than 5 years of age with a radial neck fracture and a nonossified radial epiphysis[18].

We reported a case of a Bado type I Monteggia equivalent fracture in a child aged 14 mo. To the best of our knowledge, this is the youngest patient to suffer from this injury. Furthermore, none of the reported studies have encompassed the variant described in this case report, where the radial head is unossified and invisible on plain radiography and CT. Sometimes a small fleck of metaphyseal bone around the proximal radial diaphysis can be seen, indicating SH II fracture or transverse fracture through the neck of the radius. In a study by Čepelík et al[19], the proximal radial physeal separation of SH type II was the most common among equivalents in their study. ElKhouly et al[13] reported a variant associated with SH type II injury and anterior radial head dislocation in a 10-year-old boy and proposed that Monteggia equivalent lesions with an SH fracture of the proximal radius are an unstable fracture configuration.

However, regarding SH I and SH III fractures of the radial head, the fracture line is invisible. As a result, plain radiography and CT cannot distinguish Monteggia fractures and Monteggia equivalent fractures in patients with unossified radial heads; therefore, MRI should be routinely performed. In the current case, the radial head was found to be completely separated from the neck under the assistance of MRI, and the diagnosis of a Monteggia equivalent fracture was demonstrated.

The recommended management for most Monteggia and equivalent lesions in children is closed reduction as long as the dislocated radial head can be reduced and remains stable[1,20]. However, displaced radial neck fractures with angulation greater than 30 usually require surgery, including closed reduction under sedation or anesthesia, percutaneous reduction, open reduction and fixation[21]. Anatomical reduction is indicated in the case of type I Monteggia with an inability to maintain the reduction after closed reduction but is simultaneously required to avoid subsequent limitation of motion[22,23]. If inadequate treatment is applied, equivalent lesions may lead to poor clinical and radiographic results[2]. Čepelík et al[19] warned of worse results in the treatment of Monteggia equivalents, and operative treatment was indicated in most patients in this group[19]. As reported by Olney and Menelaus, 10 of the 14 (71.4%) patients with Monteggia type I equivalent lesions involving the proximal radius required surgery[6].

In summary, the Monteggia equivalent lesion with a fracture of the radial neck and head in our patient is uncommon and has never been reported before. Therefore, it is extremely easy to misdiagnose, particularly in a child younger than 5 years of age with a cartilaginous radial head. If cartilage fracture is suspected, MRI or arthrography during reduction is strongly recommended.

This is the youngest patient to suffer from this injury. Furthermore, none of the reported studies encompassed the variant described in this case report. An accurate diagnosis to differentiate Monteggia and Monteggia equivalent lesions with Salter-Harris type I fracture of the radial head epiphysis in a child younger than 5 years of age is critical. We recommend MRI examination or arthrography during reduction, especially if the secondary ossification center has not appeared.

| 1. | Bae DS. Successful Strategies for Managing Monteggia Injuries. J Pediatr Orthop. 2016;36 Suppl 1:S67-S70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Güven M, Eren A, Kadioğlu B, Yavuz U, Kilinçoğlu V, Ozkan K. [The results of treatment in pediatric Monteggia equivalent lesions]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2008;42:90-96. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Arora S, Sabat D, Verma A, Sural S, Dhal A. An unusual monteggia equivalent: a case report with literature review. J Hand Microsurg. 2011;3:82-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Alrashidi Y. A Monteggia variant associated with unusual fracture of radial head in a young child: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2021;78:42-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bado JL. The Monteggia lesion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1967;50:71-86. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Olney BW, Menelaus MB. Monteggia and equivalent lesions in childhood. J Pediatr Orthop. 1989;9:219-223. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kamudin N, Firdouse M, Han CS, M Yusof A. Variants of Monteggia Type Injury: Case Reports. Malays Orthop J. 2015;9:23-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Soin B, Hunt N, Hollingdale J. An unusual forearm fracture in a child suggesting a mechanism for the Monteggia injury. Injury. 1995;26:407-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Zrig M, Mnif H, Koubaa M, Bannour S, Amara K, Abid A. An unusual Monteggia type I equivalent fracture: a case report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131:973-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Faundez AA, Ceroni D, Kaelin A. An unusual Monteggia type-I equivalent fracture in a child. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:584-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Drosos G, Oikonomou A. A rare Monteggia type-I equivalent fracture in a child. A case report and review of the literature. Injury Extra. 2012;43:153-156. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Clark TR, Merriott DS, Gonzales JA. Complex Monteggia fracture in a 5 year old. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2017;26:36-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | ElKhouly A, Fairhurst J, Aarvold A. The MonteggiaFracture: literature review and report of a new variant. J Orthop Case Rep. 2018;8:78-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Reina N, Laffosse JM, Abbo O, Accadbled F, Bensafi H, Chiron P. Monteggia equivalent fracture associated with Salter I fracture of the radial head. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2012;21:532-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pring ME. Pediatric radial neck fractures: when and how to fix. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32 Suppl 1:S14-S21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Skaggs DL. Elbow Fractures in Children: Diagnosis and Management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5:303-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Skaggs DL, Mirzayan R. The posterior fat pad sign in association with occult fracture of the elbow in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1429-1433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Javed A, Guichet JM. Arthrography for reduction of a fracture of the radial neck in a child with a non-ossified radial epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:542-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Čepelík M, Pešl T, Hendrych J, Havránek P. Monteggia lesion and its equivalents in children. J Child Orthop. 2019;13:560-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kalem M, Şahin E, Kocaoğlu H, Başarır K, Kınık H. Comparison of two closed surgical techniques at isolated pediatric radial neck fractures. Injury. 2018;49:618-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shabtai L, Arkader A. Percutaneous Reduction of Displaced Radial Neck Fractures Achieves Better Results Compared With Fractures Treated by Open Reduction. J Pediatr Orthop. 2016;36 Suppl 1:S63-S66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cossio A, Cazzaniga C, Gridavilla G, Gallone D, Zatti G. Paediatric radial neck fractures: One-step percutaneous reduction and fixation. Injury. 2014;45 Suppl 6:S80-S84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zimmerman RM, Kalish LA, Hresko MT, Waters PM, Bae DS. Surgical management of pediatric radial neck fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1825-1832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Rodrigues AT S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LYT