Published online Jun 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i18.4765

Peer-review started: December 22, 2020

First decision: March 11, 2021

Revised: March 22, 2021

Accepted: April 23, 2021

Article in press: April 23, 2021

Published online: June 26, 2021

Processing time: 171 Days and 0.8 Hours

Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is a malignancy that usually affects the skin of the lower extremities, and may involve internal organs. It originates from the vascular endothelium. It is well known that the development of KS is associated with human herpes virus 8 (i.e. HHV8) infections. Sporadic KS cases have mainly been found in Africa. Isolated splenic KS in Asia has rarely been reported. We present here a case of KS primarily involving the spleen in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative Chinese patient.

A 50-year-old male patient was admitted to hospital due to abdominal distension and discomfort, reduced food intake and weight loss. Medical examination revealed that the patient had moderate anemia, a low platelet count, slight fatty liver and a huge mass in the spleen. Spleen lymphoma was considered. An anti-HIV test was negative. The whole spleen was surgically excised. The final pathological diagnosis was nodular stage spleen KS, and the patient underwent total splenectomy. He recovered well and was discharged from hospital 12 d after surgery. Two weeks later, the patient developed liver metastasis and died within 1 mo after surgery.

KS is difficult to diagnose and pathological examination is necessary. KS has a poor prognosis and should be diagnosed and treated early to improve survival.

Core Tip: This case describes a rare Splenic Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative patient. The preoperative diagnosis was lymphoma, but the postoperative pathological diagnosis was KS. The operation and lack of proper postoperative treatments for KS may promote liver metastasis and death, as in this case. Improving the overall understanding of KS is paramount. Therefore, we report this case to provide KS experiences and lessons for future clinical works.

- Citation: Zhao CJ, Ma GZ, Wang YJ, Wang JH. Splenic Kaposi’s sarcoma in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative patient: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(18): 4765-4771

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i18/4765.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i18.4765

Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is a rare angioproliferative disease of the vascular endothelium[1]. KS usually affects the skin of extremities but can also involve internal organs. The development of KS involves human herpes virus 8 (HHV8) infection, regardless of any association with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (i.e. AIDS)[2]. KS has been classified into four types: classic KS, endemic African KS, iatrogenic KS, and epidemic KS[3]. Sporadic KS cases have mainly been reported in the Mediterranean/Eastern Europe, and isolated splenic KS is rare. Cutaneous KS lesions have three forms, based on histological appearance: patch lesions, plaque stage lesions, and nodular stage lesions. Clinical features of KS vary from asymptomatic to aggressive. Pain, edema, and ulceration may occur in cutaneous or mucous lesions[4]. Visceral KS may involve the liver, gastrointestinal tract, adrenal glands and the spleen[5-9], which can be life-threatening. In spleen KS, abdominal discomfort (distension or pain), and anemia were important clinical symptoms of a previously reported case and in our patient as well[9]. Differential diagnosis from other hematological diseases is required.

We present herein a rare case of KS that primarily involved the spleen in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative elderly male patient. We also review the literature in PubMed using the search terms “Kaposi’s sarcoma”, “spleen”, “HIV negative”, and “case report”.

A 50-year-old man presented with a 2-wk history of abdominal distension, reduced food intake and weight loss.

The patient began to have symptoms more than 10 d prior. He had previously visited a local clinic and received anti-inflammatory treatments to alleviate his symptoms. However, the symptoms relapsed after discontinuation of treatment. The patient was admitted to our hospital for further diagnosis and treatment. He underwent thorough laboratory examinations and was primarily diagnosed with thrombocytopenia, anemia, fatty liver and splenic space-occupying lesions. The patient was transferred from the hematology department into our ward for surgery.

The patient had a free previous medical history.

The patient had no relevant personal and family history.

On admission, the patient’s temperature was 36.5 °C, heart rate was 96 beats/min, respiratory rate was 19 breaths/min, blood pressure was 117/89 mmHg, and he had an anemic appearance. The patient had no rash or KS lesions on the skin. There were no lumps in the abdomen, the liver was not palpable, and the spleen could be touched at three transverse fingers under the ribs. There was no edema in the lower extremities.

A routine blood test showed moderate anemia with a hemoglobin level of 7.9 g/dL, thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of 35000/μL, and an albumin level of 30.5 g/L. Bone marrow biopsy showed active myeloproliferation (80%); a decrease in the ratio of granulocytes to erythrocytes was observed and immunohistochemical investigation showed CD 34(+), MPO(+), CD20(+), and CD3(T cell +). Tests for hepatitis B virus (hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B surface antibody, hepatitis B e antigen, hepatitis B e antibody, hepatitis B core antibody) were negative. Tests for HIV antigen and antibody were negative. Detection of nucleic acid for COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) was negative.

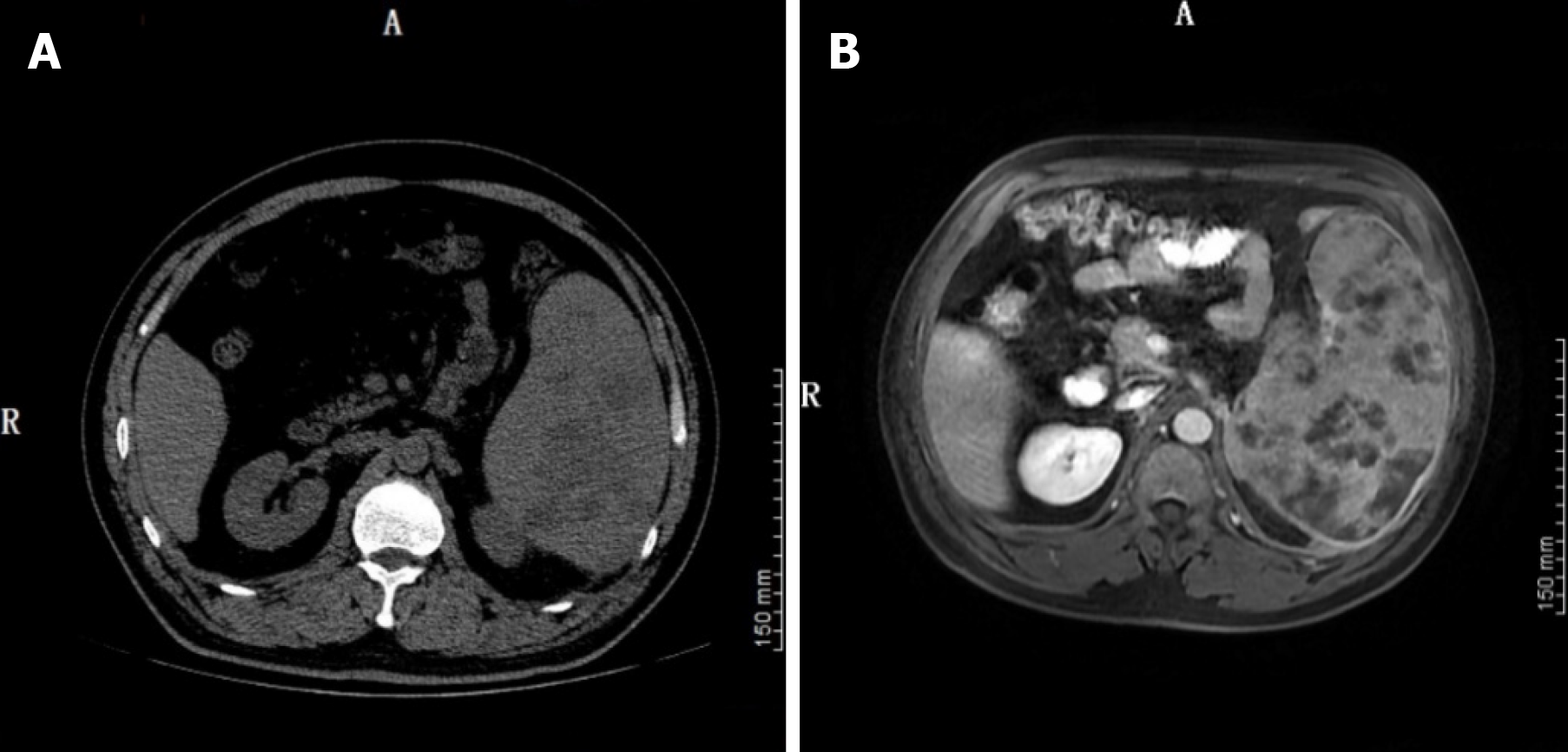

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest showed an inflammatory lesion in the right upper lobe of the lung and effusion in the left pleura. Abdominal CT suggested splenomegaly, with multiple low density shadows and mixed density shadows (Figure 1A). Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed space-occupying lesions in the spleen, which were considered to be lymphoma (Figure 1B).

During hospitalization, the patient had moderate anemia and thrombocytopenia, and was initially treated with thymosin and caffeic acid tablets to stimulate the production of blood in the bone marrow. He also received omeprazole to protect the stomach and glutathione to protect the liver. The day before surgery, the patient was administered a platelet transfusion to increase his platelet count to 50000/μL.

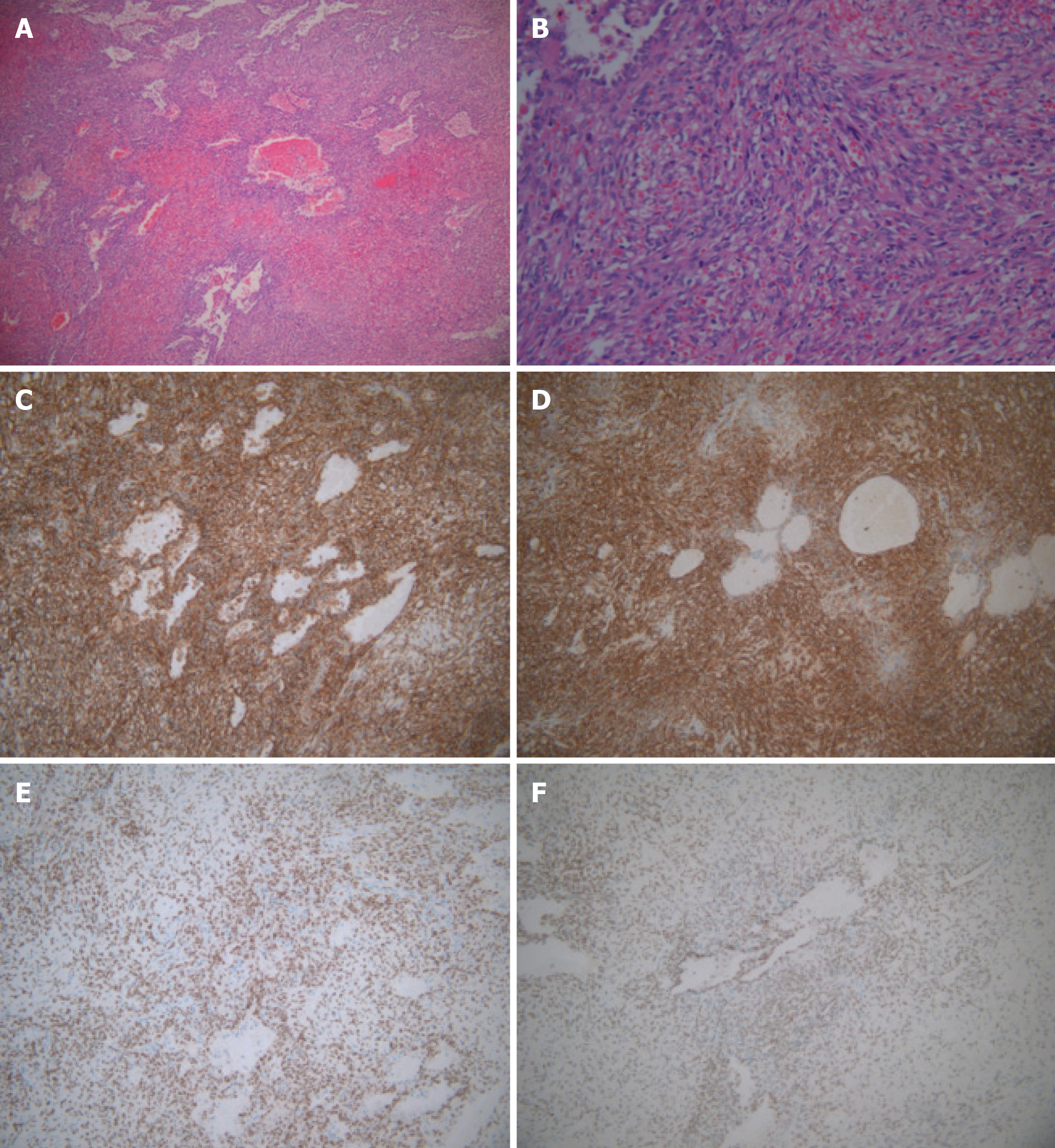

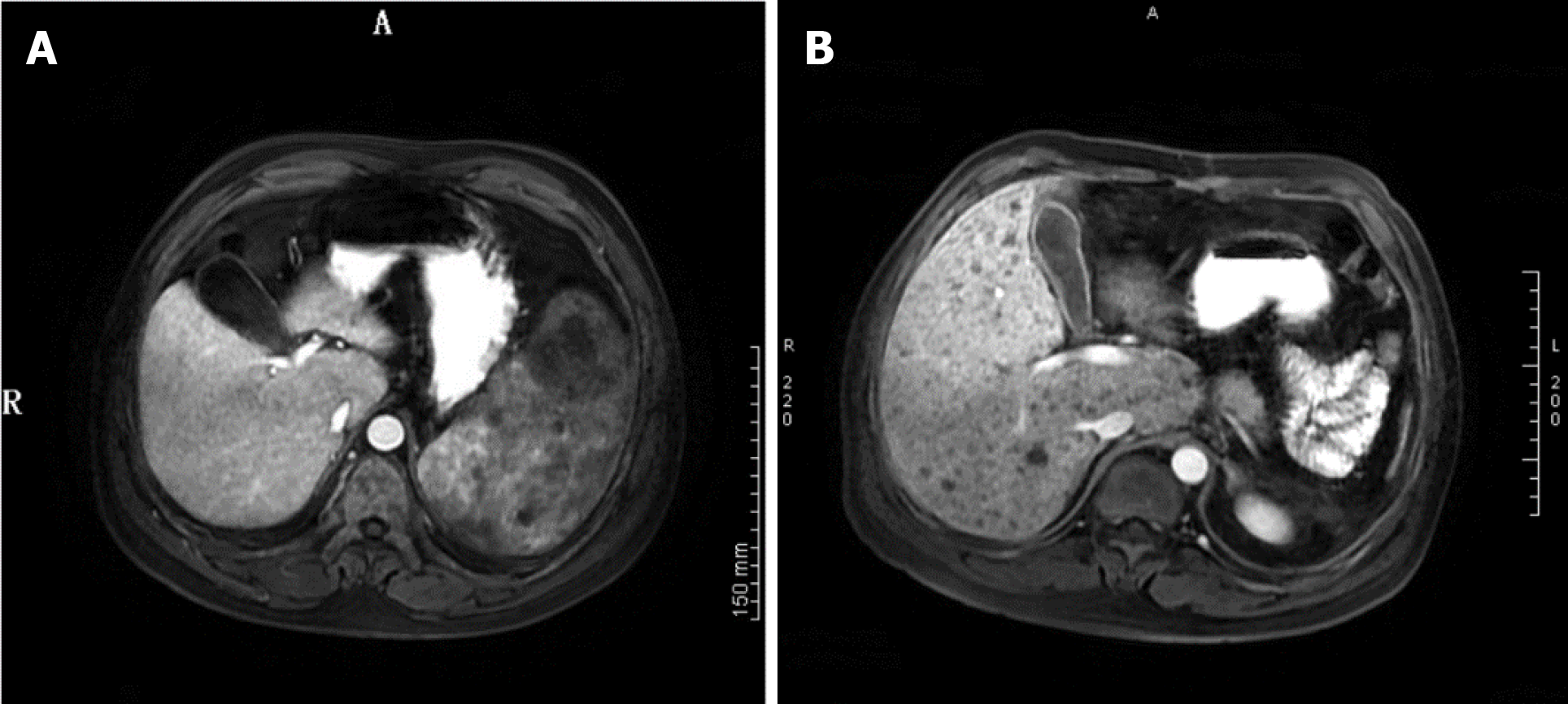

The patient underwent an elective splenectomy. Macroscopic examination revealed that the spleen was 22 cm × 18 cm × 12 cm in size, part of the spleen surface membrane was missing, and the surface was dark red with many gray and white foci. Tumor tissues were harvested and subjected to histopathological examination (Figure 2), which revealed nodular stage splenic KS. Proliferative spindle cells were crisscrossed and divided by slit-like spaces containing blood cells, which were sieve-like or beehive in shape (Figure 3A and B). Immunohistochemical examination revealed that the tumor cells were immune-positive for CD31, CD34, FIL-1, ERG, Ki-67 (10%+), CD8 (individual cells+), and D2-40 (focal+), and were immune-negative for CK, EMA, HHV8 and EBER (Figure 3C-F). The patient was readmitted to our hospital and was diagnosed with multiple liver metastases of KS based on MRI findings (Figure 4).

Based on the laboratory examinations and MRI findings, spleen lymphoma was suspected. When the patient’s condition was clinically stable, he underwent total splenectomy laparoscopically. During the operation, the liver was explored and no abnormal nodules were found. After surgery, the patient was given ceftriaxone for anti-infection and other medication to protect his liver and stomach. The patient recovered well and was discharged from hospital 12 d after surgery.

After surgery, the patient’s platelet count increased from 35000/μL to 114000/μL and then decreased 1 wk later. The patient’s anemia did not resolve. Two weeks after discharge, the patient was readmitted to the hospital due to severe jaundice. MRI showed that the patient had developed multiple liver metastases of KS, and laboratory examinations revealed impaired liver function. Unfortunately, the patient did not undergo further chemotherapy and died 1 wk later.

KS lesions are mainly localized on the skin of distal extremities but can also involve lymph nodes and visceral organs without skin involvement[3,10]. KS primarily located in the spleen in non-HIV patients has rarely been reported. Sarode et al[9] reported the first case of splenic KS in 1991. Mikami et al[11] reported a case of Kaposi-like variant of splenic angiosarcoma lacking HHV8 DNA in an HIV-negative patient in 2002. To our knowledge, we report the third case of KS located in the spleen in an HIV-negative patient. These cases have similar clinical features and malignant behavior. KS lesions have three stages: patch stage, plaque stage and nodular stage[4]. Based on low-magnification findings, our patient had nodular stage KS.

The pathogenesis of KS has still not been clearly elucidated. It is uniformly associated with HHV8 infection, irrespective of HIV infection history[12]. Szajerka et al[3] reviewed the multifactorial etiopathogenesis of KS, including the HIV, iron and other minerals, insects and saliva, and HHV8 infection. Ensoli et al[13] indicated that KS is the result of the complex interplay between HHV8 and immunologic, genetic and environmental factors. In our case, unfortunately, tumor cells were immuno-negative for HHV8 and we were unable to test for HHV8 DNA in the blood sample. However, this does not indicate that the present case did not have HHV8 infection. In addition to HHV8, cyclin D1 is also an important molecular marker to distinguish KS from angiosarcoma[14].

The clinical manifestations of splenic KS vary, and mainly include anemia, abdominal discomfort (abdominal pain or distension), and metastasis. In two reported cases, the patients had abdominal pain, and the chief complaint in our case was abdominal distension. The first reported case developed metastasis in the liver, mesentery, pleura, and lymph nodes[9]. The second case developed liver and bone marrow metastases[11]. Four weeks after surgery, the present patient was found to have liver metastasis when he was readmitted to the hospital due to jaundice. We speculate that surgery promoted tumor metastasis. It is possible that if the patient receives chemotherapy after surgery, tumor metastasis may be delayed.

Selection of the management strategy for KS depends on the location and variant of KS[15]. Epidemic KS often regresses with highly active antiretroviral therapy[16,17] and potent antiretroviral medication can dramatically reduce the incidence of KS in HIV patients[18]. For visceral KS, surgery, radiotherapy and systemic chemotherapy are necessary. The patients with splenic KS underwent splenectomy and chemotherapy according to the reports[9,11]. In our case, the whole spleen was successfully excised, but failed to improve the patient’s condition and accelerated liver metastasis. Although biopsy can provide correct diagnosis, considering that splenic biopsy may increase the risk of tumor metastasis, we did not perform biopsy before surgery. The prognosis of splenic KS is very poor. Patients with widespread visceral involvement are poorly responsive to treatment[4]. The present patient only lived 3 mo from the time he felt sick. Up to date, we have insufficient knowledge about KS. A splenic tumor does not explain megaloblastic anemia; therefore, the diagnosis of KS should be established until the etiology is explained. Our patient should have received early appropriate treatment for splenic KS consisting of surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

We report a rare splenic KS in an HIV-negative patient with atypical clinical manifestations. MRI suggested splenic lymphoma and splenectomy was performed. The pathologic diagnosis was KS.

We are grateful to the patient and his family for providing a signed informed consent. We acknowledge the contribution by our study team members. We would like to thank Professor Gengyin Zhou from the Department of Pathology of Qilu Hospital and Qianfeshan Hospital for assistance in the pathological diagnosis.

| 1. | Ozmen H, Baba D, Kacagan C, Kayikci A, Cam K. Case report: HIV negative isolated scrotal Kaposi's sarcoma. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:1086-1087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cathomas G. Human herpes virus 8: a new virus discloses its face. Virchows Arch. 2000;436:195-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Flecher CD, Ridge JA, Mertens F. Skeletal muscle tumors. World Health Organization classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4th ed, Lyon: LARC Press, 2013: 151-153. |

| 5. | Van Leer-Greenberg B, Kole A, Chawla S. Hepatic Kaposi sarcoma: A case report and review of the literature. World J Hepatol. 2017;9:171-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kahl P, Buettner R, Friedrichs N, Merkelbach-Bruse S, Wenzel J, Carl Heukamp L. Kaposi's sarcoma of the gastrointestinal tract: report of two cases and review of the literature. Pathol Res Pract. 2007;203:227-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bisceglia M, Minenna E, Altobella A, Sanguedolce F, Panniello G, Bisceglia S, Ben-Dor DJ. Anaplastic Kaposi's Sarcoma of the Adrenal in an HIV-negative Patient With Literature Review. Adv Anat Pathol. 2019;26:133-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Trésallet C, Thibault F, Cardot V, Baleston F, Nguyen-Thanh Q, Chigot JP, Menegaux F. [Spontaneous splenic rupture during intrasplenic Kaposi's sarcoma in an HIV-positive patient]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29:1296-1297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sarode VR, Datta BN, Savitri K, Singh K, Bhasin D. Kaposi's sarcoma of spleen with unusual clinical and histologic features. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1991;115:1042-1044. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, Scuderi L. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206; quiz 207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mikami T, Saegusa M, Akino F, Machida D, Iwabuchi K, Hagiwara S, Okayasu I. A Kaposi-like variant of splenic angiosarcoma lacking association with human herpesvirus 8. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126:191-194. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, Lee F, Culpepper J, Knowles DM, Moore PS. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science. 1994;266:1865-1869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4341] [Cited by in RCA: 4180] [Article Influence: 130.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 13. | Ensoli B, Sgadari C, Barillari G, Sirianni MC, Stürzl M, Monini P. Biology of Kaposi's sarcoma. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:1251-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kennedy MM, Biddolph S, Lucas SB, Howells DD, Picton S, McGee JO, Silva I, Uhlmann V, Luttich K, O'Leary JJ. Cyclin D1 expression and HHV8 in Kaposi sarcoma. J Clin Pathol. 1999;52:569-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Fatahzadeh M. Kaposi sarcoma: review and medical management update. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;113:2-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Murdaca G, Campelli A, Setti M, Indiveri F, Puppo F. Complete remission of AIDS/Kaposi's sarcoma after treatment with a combination of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and one non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor. AIDS. 2002;16:304-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Diz Dios P, Ocampo Hermida A, Miralles Alvarez C, Vázquez García E, Martínez Vázquez C. Regression of AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma following ritonavir therapy. Oral Oncol. 1998;34:236-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vanni T, Sprinz E, Machado MW, Santana Rde C, Fonseca BA, Schwartsmann G. Systemic treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma: current status and perspectives. Cancer Treat Rev. 2006;32:445-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Yildirim M S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL