Published online Jun 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i18.4772

Peer-review started: December 29, 2020

First decision: March 27, 2021

Revised: April 8, 2021

Accepted: May 6, 2021

Article in press: May 6, 2021

Published online: June 26, 2021

Processing time: 163 Days and 21.1 Hours

Syringocystadenoma papilliferum (SCAP) represents a rare, noncancerous adnexal tumor predominantly presenting at birth or in early childhood.

In this study, a 35-day-old girl was admitted to Kunming Children’s Hospital in October 2019 due to a lesion in the right frontotemporal region since birth. The surface of the lesion was bright red, granular, and papillary and easily bled upon touch, with about 1.5 cm × 4 cm in size. A subcutaneous mass was felt at the base of the lesion, with a size of about 3 cm × 5 cm. Dermatoscopy showed that the skin lesion was lobular and crumby. The lesion center was reddish or white, while the edges were white or yellowish band-like. There were polymorphic vascular structures and white radial streaks in the lesion, with some vascular clusters scattered. Pathological examination showed papilloma-like hyperplasia of the epidermis, with the epidermis partly sinking into the dermis to form several cystic depressions. Combining clinical and histopathological features, the child was diagnosed with SCAP. Follow-up is ongoing, and surgical resection will be performed.

This was a special clinical manifestation of SCAP, which complements the clinical manifestations of the disease and provides new insights for the diagnosis and differentiation of neonatal skin tumors.

Core Tip: Syringocystadenoma papilliferum (SCAP) is a benign skin adnexal tumor whose origin and pathogenesis are unknown. The case reported here had a special clinical manifestation of SCAP. At birth, the skin lesion was bright red, papillary, and granulation-like, with a subcutaneous mass, surface exudation, and ease of bleeding upon touch, similar to the mature skin lesions of previous cases that had increased with age. The girl described in this report had a special clinical manifestation of SCAP, which complements the clinical manifestations of the disease and provides new insights for the diagnosis and differentiation of neonatal skin tumors.

- Citation: Jiang HJ, Zhang Z, Zhang L, Pu YJ, Zhou N, Shu H. Neonatal syringocystadenoma papilliferum: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(18): 4772-4777

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i18/4772.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i18.4772

Syringocystadenoma papilliferum (SCAP), also known as syringocystadenomatosus papilliferus, represents a rare, noncancerous adnexal tumor presenting at birth or in early childhood in half of cases and developing during puberty in another 15%-30% of cases[1]. The lesion has various clinical signs (e.g., presenting as a hairless area on the scalp); SCAP is believed to be related to sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn[2]. There are three known clinical forms of SCAP, including plaque, solitary nodular, and linear, and the majority of lesions are found in the head and neck region. SCAP is associated with other noncancerous adnexal tumors, including nevus sebaceous, apocrine nevus, tubular apocrine adenoma, apocrine hidrocystoma, apocrine cystadenoma, and clear cell syringoma[3]. We here report a 35-day-old girl admitted to Kunming Children’s Hospital in October 2019 due to a lesion in the right frontotemporal region from birth, who was diagnosed with SCAP based on clinical and histopathological features.

A 35-day-old girl was admitted to Kunming Children’s Hospital in October 2019 due to a lesion in the right frontotemporal region.

The lesion was found at birth, as a subcutaneous mass with granular and papillary surface. The patient was firstly diagnosed with “cavernous hemangioma”, without treatment. The skin lesion easily bled upon touch, and showed repeated ulceration, erosion, and scab formation. There was no obvious enlargement of the lesion and subcutaneous mass from birth until now.

The patient was born at 38 wk of pregnancy, with a birth weight of 3.1 kg and no perinatal infection or suffocation.

The patient had no specific personal and family history.

Physical examination revealed good general condition. The vital signs were stable, and no other abnormality was found. Dermatological examination showed a red lesion in the right frontotemporal region, with thick brown scab on the surface. After cleaning the scab, the surface of the skin lesion was bright red, appearing like granulation tissue. The lesion was granular and papillary and easily bled upon touch, with about 1.5 cm × 4 cm in size. A small amount of pale yellow thin secretion was observed on the lesion surface. There was a pedicle at the base of the skin lesion. A subcutaneous mass was felt at the base of the lesion, with slightly hard texture and a clear boundary. The mass expanded beyond the red area, with a size of about 3 cm × 5 cm. The surrounding skin had no redness or swelling, and the mass showed no tenderness (Figure 1).

Blood routine test showed lymphocyte count at 4.51 × 109/L (1.0-3.0 × 109/L), lymphocyte percentage at 60.60% (20%-40%), neutrophil percentage at 30.80% (50%-70%), platelet count at 528 × 109/L (100-300 × 109/L), platelet hematocrit at 0.52% (0.108%-0.282%), and platelet distribution width at 10.0 fL (15.5-18.1 fL). The remaining indicators were unremarkable. Surface secretions were cultured for 48 h, and three plasma coagulase tests were negative; meanwhile, mixed growth of Staphylococcus was detected, with no Haemophilus isolated. Stool routine, urine routine, liver function, and kidney function tests were normal. These laboratory findings did not point to any specific diagnosis.

Skull plain computed tomography (CT) and enhanced scans showed slightly thickened subcutaneous soft tissue of the right temporal region, and the stripes showed a high-density shadow, with a CT value of about 31 HU. Enhanced CT showed enhancement, with a CT value of about 61 HU. No obvious signs of damage were seen in the adjacent skull. There were no lesions with definite abnormal density in the brain parenchyma (no obvious abnormal enhancement). There was no enlargement, stenosis, or occlusion in the ventricular system; no widening of subarachnoid space of each ventricle or displacement of the midline structure was found.

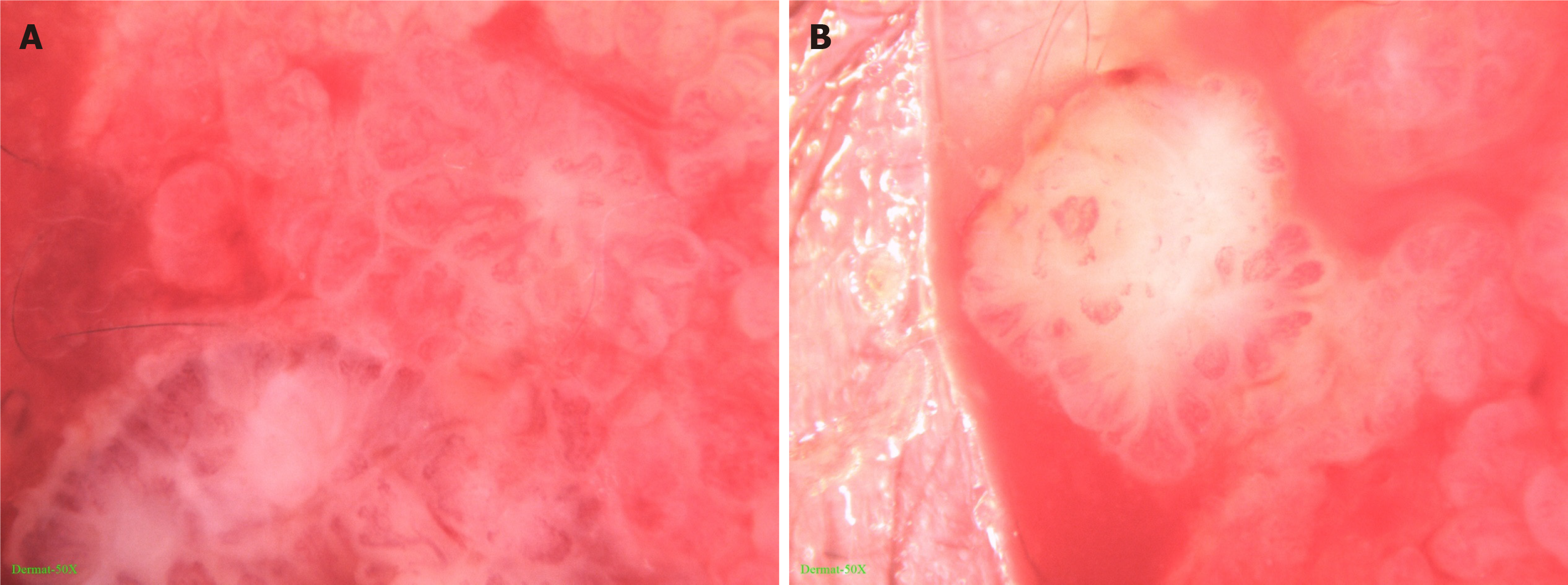

Dermatoscopy showed that the skin lesion was lobular and crumby. The lesion center was reddish or white, while the edges were white or yellowish band-like. There were polymorphic vascular structures and white radial streaks in the lesion, with some vascular clusters scattered (Figure 2).

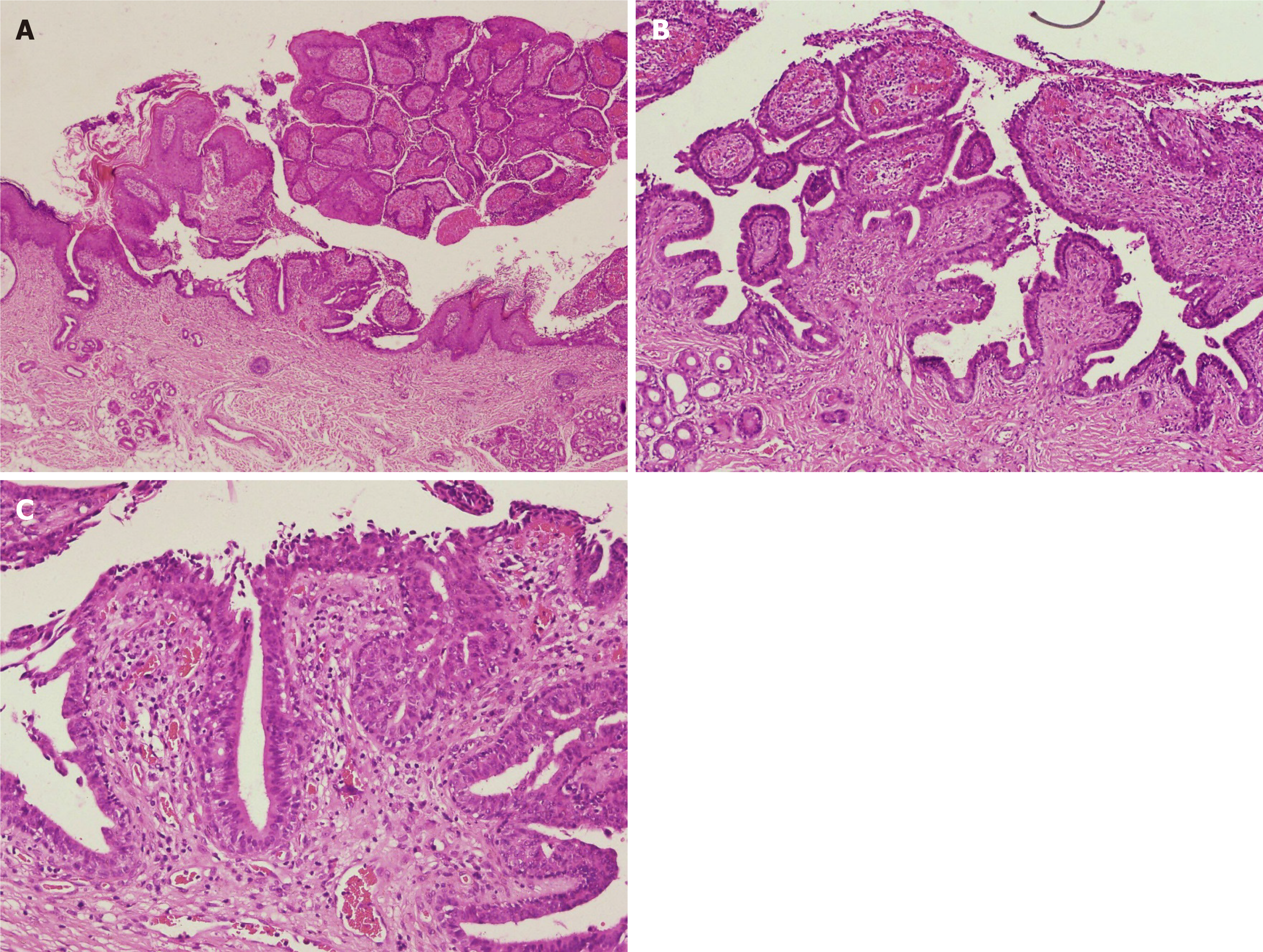

Pathological examination showed papilloma-like hyperplasia of the epidermis, with the epidermis partly sinking into the dermis to form several cystic depressions, lined with stratified squamous epithelium. Glandular cavity-like structures were seen in the dermis, with some opened into the epidermis. A large number of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells infiltrated in the interstitial area was observed, as well as splinter hemorrhage. The cavity wall and villous epidermis of the glandular cavity were composed of two layers of epithelial cells; the inner layer included columnar cells, with oval and eosinophilic nuclei and abundant cytoplasm; apocrine secretion was observed (Figure 3).

Combining clinical and histopathological features, the child was diagnosed with SCAP[1-3].

Due to young age, the patient was recommended to return to the hospital at 6 mo of age for elective surgery.

At the end of February 2020, the girl’s parents were contacted by telephone. The child was 5 months old. The lesion had not increased significantly, the surface was scabbed, and it still easily bled upon touch, similar to the condition at 1 month of age. There was no obvious enlargement of or protuberance in the subcutaneous mass. Follow-up is ongoing, and surgical resection will be performed.

SCAP was a benign skin adnexal tumor whose origin and pathogenesis are unknown. Some scholars believe that it originates from large and small sweat glands or pluripotent stem cells[4]. It was firstly reported by Petensen in 1982 (reference unavailable), and there are currently few reported clinical cases. SCAP shows a smooth surface at the beginning and a verrucous bulge later. The clinical manifestations of individual skin lesions are very different and may include an infiltrating patch, a papilloma, and verrucous or keratinized nodules. The case reported here had a special clinical manifestation of SCAP. At birth, the skin lesion was bright red, papillary, and granulation-like, with a subcutaneous mass, surface exudation, and ease of bleeding upon touch, similar to the mature skin lesions of previous cases that had increased with age.

Most SCAP occur in the head and neck region, and unusual locations comprise the buttock, vulva and scrotum, pinna, eyelid, outer ear canal, postoperative scar, scalp, nipple, thigh, axilla, and back[3]. Several reports have described cases with SCAP originating from the nevus sebaceous in older women[5-7]. However, no previous clinical report described a case similar to the present one. SCAP could be accompanied by other skin tumors, such as sebaceous nevus, apocrine adenoma, ductal eccrine carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, trichoepithelioma, and cutaneous horn. In the current case, the patient was young and diagnosed at an early age, and the above-mentioned complications were not found.

Currently, SCAP is mainly treated by laser, cryogen spray cooling, or surgical resection. Surgical resection would be the most effective treatment method at the present stage. However, for lesions on the head and face, especially large ones, it is necessary to consider the appearance after surgical resection, and the possibility that incomplete resection is prone to recurrence and the potential for transformation into cancer[8,9]. Recently, it was found that the pathogenesis of SCAP might be associated with HRAS and BRAF V600 mutations[10-12]. Vemurafenib could target cells with V600E mutations, and might also benefit SCAP patients with BRAF V600E mutations, bypassing the shortcomings of existing treatment methods[12,13]. Further assessment of the current patient will determine whether she has such mutations.

SCAP was a benign skin adnexal tumor whose origin and pathogenesis are unknown. The case reported here had a special clinical manifestation of SCAP. At birth, the skin lesion was bright red, papillary, and granulation-like, with a subcutaneous mass, surface exudation, and ease of bleeding upon touch, similar to the mature skin lesions of previous cases that had increased with age. The girl described in this report had a special clinical manifestation of SCAP, which complements the clinical manifestations of the disease and provides new insights for the diagnosis and differentiation of neonatal skin tumors.

| 1. | Vyas SP, Kothari DC, Goyal VK. Syringocystadenoma papilliferum of scalp: A rare case report. IJSS. 2015;2:182-185. |

| 2. | Bruschini L, Ciabotti A, De Vito A, Forli F, Cambi C, Ciancia EM, Berrettini S. Syringocystadenoma Papilliferum of the External Auditory Canal. Am J Case Rep. 2017;18:520-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Xu D, Bi T, Lan H, Yu W, Wang W, Cao F, Jin K. Syringocystadenoma papilliferum in the right lower abdomen: a case report and review of literature. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:233-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yamamoto O, Doi Y, Hamada T, Hisaoka M, Sasaguri Y. An immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of syringocystadenoma papilliferum. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:936-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Léda LDSB, Lins MDSVS, Leite EJDS, Cardoso AEC, Houly RLS. Syringocystadenoma papilliferum combined with a tubular apocrine adenoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:721-723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang F, Wu Y, Zheng Z, Bai Y. Syringocystadenoma papilliferum and trichoblastoma arising in the nevus sebaceous. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2018;61:106-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chandramouli M, Sarma D, Tejaswy K, Rodrigues G. Syringocystadenoma Papilliferum of the Scalp Arising from a Nevus Sebaceous. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2016;9:204-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lewandowicz E, Zieliński T, Iljin A, Fijałkowska M, Kasielska-Trojan A, Antoszewski B. Surgical treatment of skin lesions in lupus erythematosus. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:405-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Suh JD, Chiu AG. What are the surveillance recommendations following resection of sinonasal inverted papilloma? Laryngoscope. 2014;124:1981-1982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mitsui Y, Ogawa K, Takeda M, Kuwahara M, Fukumoto T, Asada H. Grouped apocrine gland component associated with sporadic syringocystadenoma papilliferum: A case report and BRAFV600E mutation analysis of the two components. J Dermatol. 2019;46:e395-e398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Konstantinova AM, Kyrpychova L, Nemcova J, Sedivcova M, Bisceglia M, Kutzner H, Zamecnik M, Sehnalkova E, Pavlovsky M, Zateckova K, Shvernik S, Spurkova Z, Michal M, Kerl K, Kazakov DV. Syringocystadenoma Papilliferum of the Anogenital Area and Buttocks: A Report of 16 Cases, Including Human Papillomavirus Analysis and HRAS and BRAF V600 Mutation Studies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:281-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Levinsohn JL, Sugarman JL, Bilguvar K, McNiff JM, Choate KA, The Yale Center For Mendelian Genomics. Somatic V600E BRAF Mutation in Linear and Sporadic Syringocystadenoma Papilliferum. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2536-2538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bollag G, Hirth P, Tsai J, Zhang J, Ibrahim PN, Cho H, Spevak W, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Habets G, Burton EA, Wong B, Tsang G, West BL, Powell B, Shellooe R, Marimuthu A, Nguyen H, Zhang KY, Artis DR, Schlessinger J, Su F, Higgins B, Iyer R, D'Andrea K, Koehler A, Stumm M, Lin PS, Lee RJ, Grippo J, Puzanov I, Kim KB, Ribas A, McArthur GA, Sosman JA, Chapman PB, Flaherty KT, Xu X, Nathanson KL, Nolop K. Clinical efficacy of a RAF inhibitor needs broad target blockade in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nature. 2010;467:596-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1536] [Cited by in RCA: 1465] [Article Influence: 91.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Pandey A S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH