Published online Sep 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i18.4259

First decision: May 15, 2020

Revised: May 22, 2020

Accepted: August 14, 2020

Article in press: August 14, 2020

Published online: September 26, 2020

Processing time: 162 Days and 15.4 Hours

Extremely premature infants have poor vascular conditions. Operators often choose deep veins such as the femoral vein and axillary vein to peripherally insert central catheters, and these vessels are often accompanied by arteries; thus, it is easy to mistakenly enter the artery.

The case of an extremely premature infant (born at gestational age 28+3) in whom the left upper extremity artery was accidentally entered during peripheral puncture of the central venous catheter is reported. On the 19th day of hospitalization, the index finger, middle finger and ring finger of the left hand were rosy, the left radial artery and brachial artery pulse were palpable, the recovery was 95%, and the improvement was obvious. At discharge 42 d after admission, there was no abnormality in fingertip activity during the follow-up period.

Arterial embolization in preterm infants requires an individualized treatment strategy combined with local anticoagulation and 2% nitroglycerin ointment for local tissue damage caused by arterial embolism in the upper limb. Continuous visualization of disease changes using image visualization increases the likelihood of a good outcome.

Core Tip: Arterial embolization in preterm infants requires individualized treatment strategies combined with local anticoagulation and 2% nitroglycerin ointment for local tissue damage caused by arterial embolism in the upper limbs of preterm infants, and continuous visualization of disease changes using image visualization, which can lead to a good outcome.

- Citation: Huang YF, Hu YL, Wan XL, Cheng H, Wu YH, Yang XY, Shi J. Arterial embolism caused by a peripherally inserted central catheter in a very premature infant: A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(18): 4259-4265

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i18/4259.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i18.4259

Extremely premature infants have poor vascular conditions. Operators often choose deep veins such as the femoral vein and axillary vein for peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs), and these vessels are often accompanied by arteries; thus, it is easy to mistakenly enter the artery[1-5]. There are methods to follow during and after placement of the tube. During tube placement, there may be clinical manifestations of jet-like, pulsating bright red blood return and high pressure of the flushing tube after mistaken insertion into the artery. If the blood return is not obvious, it is likely that the PICC was successful. Blood gas analysis is performed to check the blood oxygen partial pressure. Generally, the venous blood oxygen partial pressure is lower than that of arterial blood, the carbon dioxide partial pressure is higher than that of arterial blood, and the oxygen saturation is approximately 70%.

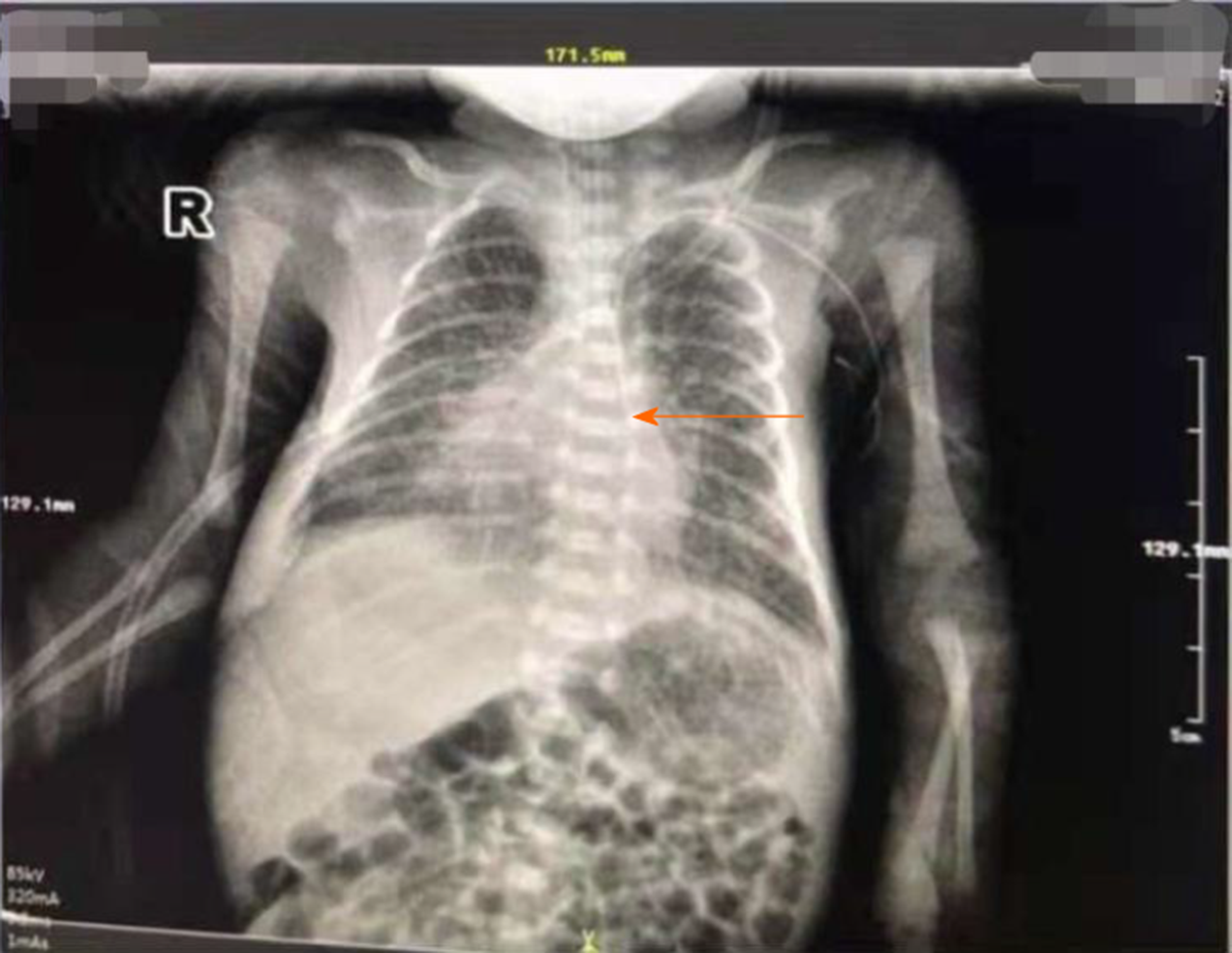

If the blood gas analysis results indicate that the blood gas oxygen pressure and the normal percutaneous blood oxygen saturation are extremely similar, it is highly suspected that the artery has been mistakenly entered[6]. In addition, an X-ray is needed to confirm the tip position after catheter placement[7-9].

Normal PICC tip positioning for upper limb puncture is usually the middle and lower segment of the superior vena cava 1/3 located on the right side of the spine[10]. If the catheter is deflected along the left side of the spine, there are two possibilities: mistaken entry into the arteries or the left permanent superior vena cava. In the case of children with this condition, during the puncture process and after catheter placement, multiple methods should be used to identify the arteries mistakenly entered early and to enable the implementation of proactive measures.

In this study, the case of an extremely premature infant in whom the left upper extremity artery was accidentally entered during peripheral puncture of the central venous catheter is reported. A literature review was also performed.

Eleven days after premature delivery, black and purple coloring of multiple fingers of the left hand was observed.

A male child 11+ d was admitted to the hospital on August 14, 2019. The infant was born at 28 wk and 3 d of pregnancy with a birth weight of 1100 g and an Apgar score of 5-7-8 points.

Not available.

Multiple fingers on the left hand were black and purple. For further treatment, the infant was transferred to the Neonatal Department of our hospital. On admission, physical examination showed the following: the palm of the left hand was blue and purple; the left index finger, middle finger, and ring finger knuckles were black; the border was unclear; and the local skin temperature was slightly cool. The left radial artery pulsation was not found, and the left brachial artery pulsation was weak.

Blood tests in the laboratory showed that the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) was 110.1 s and hemoglobin (HGB) was 132 g/L.

Vascular color Doppler ultrasound showed left radial artery embolism and suspected thrombus in the left brachial artery. The patient's chest X-ray film, obtained outside the hospital, showed that the catheter was located on the left side of the spine (PICC) (Figure 1).

Left hand fingertip vascular embolism.

On the day of admission, 1.5 mg/kg low-molecular-weight heparin sodium was injected subcutaneously (hypodermic injection, ih, q12h. 14:33), the APTT was 110.1 s, fg was 148 g/L, and HGB was 132 g/L. The low-molecular-weight heparin sodium dosage was changed to 2.0 mg/kg ih q12h. On the seventh day of admission, the darkened fingertips had improved slightly, but left radial artery pulsation was not found, and the left brachial artery pulsation had weakened. Sodium 2.5 mg/kg, ih, q12h was administered. To correct coagulation function during treatment, the infant was given fresh frozen plasma on the 2nd and 13th days of admission.

Phentolamine was applied externally on the black and purple parts of the fingers. On the second day of admission, the color of the fingers continued to darken, and the treatment was changed to an external coating of Xiliaotu with a warm saline wet dressing that was replaced every 4 h. On the 5th day of admission, the index finger and ring finger became darker, the middle finger still showed obvious darkening, the left brachial artery pulsation was weakened, and the left radial artery pulsation was still not found. Then, 0.2% nitroglycerin ointment was applied with a warm saline wet compress, which was changed every 4 h.

Photographs were taken before and after each local treatment. The photographs were immediately uploaded to the WeChat Nursing Quality Control Management Group, which is convenient for the timely comparison and tracking of fingertip skin recovery and the modification of treatment plans if necessary.

On the 5th day of admission, the darkened fingertips were slightly better than before. On the 10th day of admission, the left index finger, middle finger, and ring finger turned ruddy, and a yellow-like tissue region of approximately 0.5 cm × 0.3 cm was visible on the fingertips. The left radial artery and brachial artery had weak pulses. On the 14th day of admission, color Doppler ultrasound showed no thrombus in the left upper limb. On the 19th day of admission, the index finger, middle finger, and ring finger of the left hand were rosy, and bruising was visible on the middle fingertips. No exudation or secretions were observed, the left radial/brachial pulsation was palpable, and the degree of recovery was 95%, showing obvious improvement (Figure 2).

The neonatal coagulation system is immature, and coagulation and fibrinolysis maintain a delicate balance. When the balance is disrupted, bleeding or thrombosis easily occurs[11,12]. The rates of neonatal thromboembolic diseases reported in Germany and Canada in 1997 were 0.051% and 2.4%, respectively, and a recent study showed that the incidence of neonatal thromboembolic diseases has increased to 6.6%, accounting for 70% of all neonatal mortality[13-15]. It has been reported in the literature that 29% of 75 thromboembolic events are due to arterial thrombosis[15], most of which are related to iatrogenic factors such as catheterization and vascular puncture. Saracco et al[15] showed that the average fetal age at arterial embolism is 31 wk, and Conti et al[13] also noted in the literature that premature infants are at high risk of arterial thrombosis, which is related to factors such as concurrent infections, high blood coagulation status, and the need to puncture arterial blood vessels for blood pressure monitoring or specimen collection during hospitalization[16]. This pediatric patient was born at 28 gestational weeks and had a history of puncture. This is consistent with the descriptions of Saracco et al[15] and Conti et al[13]. In 2012, the American Thoracic Association published the 9th edition of the guidelines for antithrombotic therapy for newborns, which included safe and effective treatment measures, but the tracking and evaluation of complications are still controversial. In addition, most of the recommended treatments in the guidelines are based on data from studies of adults or case reports, and most of the evidence is grade 2C. Therefore, the treatment of neonatal thrombotic diseases still needs to be evaluated step by step according to the development of and change in the disease, and then the corresponding individualized treatment strategy can be adopted.

The 9th edition of the U.S. Guidelines for Antithrombotic Therapy for Newborns note that due to the risk of bleeding, thrombolytic therapy is not allowed in preterm infants less than 32 wk of age[17] without life-threatening conditions or the possibility of amputation. Therefore, anticoagulation therapy has become the preferred solution for thromboembolism in premature infants. Low-molecular-weight heparin has fewer monitoring requirements than ordinary heparin, is a simple operation, has a lower risk of bleeding and is often used as an anticoagulant treatment. Goldsmith et al[18] reported low use in the literature. The effectiveness of molecular heparin sodium in the treatment of thrombosis in preterm infants[18] and reports in the literature indicate that the use of low-molecular-heparin calcium can successfully treat children with thrombosis. In this case, it is considered that low-molecular-heparin calcium can cause subcutaneous nodules due to calcium salt deposition; thus, Kesai was selected as the therapeutic drug.

In this case, phentolamine was applied topically to the injured fingertips after hospitalization, and Xiliaodu was applied externally, but the treatment effect was poor. Following a literature review, it was found that 2% nitroglycerin was topically applied both nationally and internationally[19]. Improved tissue ischemic damage was reported in preterm infants. Nitroglycerin (2%) can relax vascular smooth muscles, relax blood vessels, and relieve spasms after absorption through the skin. Moreover, nitroglycerin can stimulate the collateral circulation to increase blood perfusion in ischemic areas. In addition, nitric acid, which is not converted from glycerol, can inhibit platelet aggregation and adhesion and prevent thrombosis. Some scholars[20] believe that 2% nitroglycerin coating is associated with no bleeding risk, has significant advantages over anticoagulation therapy, and can be used alone to treat thrombosis caused by ischemic tissue damage. However, there is also literature to show that nitroglycerin coating can only be used for tissue damage during vasospasm[21]. In addition, the treatment of neonatal tissue damage with nitroglycerin deficiency lacks evidence from clinical experimental studies with large samples and a clear standardized protocol. Considering that fingertip tissue damage in children already indicates ischemic necrosis, 2% nitroglycerin ointment is applied as a synergistic means for anticoagulation therapy.

The responsible nurse in each class evaluated the finger color, skin temperature, and arterial pulsation of the child and described it on the nursing record and the bedside transfer sheet. In addition, the nurse also took photographs of the injured fingertip and uploaded them to the quality of care control WeChat group of the management team. Pictorial records of the fingertips can improve the initiative of the staff in the field to treat the condition in time and focus on observation. Additionally, this method prevents poor communication at the handover caused by the subjective description in the text and ensures the continuity of monitoring of the injury site in the nursing field.

The management WeChat group to which the photographs were uploaded enabled the quality control staff to track the changes in the patient's condition in a timely manner and facilitate remote guidance. The child's black and purple ring finger was decreased on the 3rd day of admission. The blackening of the index finger and ring finger on the 5th day of admission was reduced, the middle finger still showed obvious blackening, the left brachial artery pulsation was weakened, and the left radial artery pulsation was still not found. Furthermore, on the 10th day of admission, on the left index finger, middle finger, and ring finger, a ruddy region with a yellow color of approximately 0.5 cm × 0.3 cm was visible on the fingertips. No seepage or secretions were observed; the left radial artery and brachial artery developed a weak pulse. On the 14th day of admission, blood vessel ultrasound showed that no thrombus was seen in the left upper limb. On the 19th day of admission, the index finger and middle finger of the left hand were assessed, and red, visible petechiae of the middle finger and no exudate or secretions were observed. The left radial artery and brachial artery pulse reached a degree of recovery of 95%, improving significantly.

When the PICC assessment reveals that the artery has been mistakenly entered, the PICC should be removed immediately, and the blood should be pressurized to stop bleeding. Additionally, limb circulation disorders should be closely monitored. When arterial embolism occurs, it should be evaluated step by step according to the development of the disease, and then the corresponding individualized treatment strategy should be adopted. The combination of anticoagulation therapy and topical application of 2% nitroglycerin ointment was used to treat local tissue damage caused by arterial embolism in the upper limbs of the preterm infant. The visual changes were used to continuously track the changes in the condition, and the outcome was good.

Arterial embolization in the preterm infant required an individualized treatment strategy combined with local anticoagulation and 2% nitroglycerin ointment for local tissue damage caused by arterial embolism in the upper limb. Continuous visualization of disease changes using image visualization increases the likelihood of a good outcome.

| 1. | Del Prato F, Di Matteo A, Messina F, Napolitano M. [PICC: central venous access by the peripheral route. Medical-nursing aspects]. Minerva Pediatr. 2010;62:161-163. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Kumar J, K C S, Mukhopadhyay K, Ray S. A misplaced peripherally inserted central catheter presenting as contralateral pleural effusion. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | van den Berg J, Lööf Åström J, Olofsson J, Fridlund M, Farooqi A. Peripherally inserted central catheter in extremely preterm infants: Characteristics and influencing factors. J Neonatal Perinatal Med. 2017;10:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Corzine M, Willett LD. Neonatal PICC: one unit's six-year experience with limiting catheter complications. Neonatal Netw. 2010;29:161-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ozkiraz S, Gokmen Z, Anuk Ince D, Akcan AB, Kilicdag H, Ozel D, Ecevit A. Peripherally inserted central venous catheters in critically ill premature neonates. J Vasc Access. 2013;14:320-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pignotti MS, Messineo A, Indolfi G, Donzelli G. Bilateral consolidation of the lungs in a preterm infant: an unusual central venous catheter complication. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004;14:957-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yang L, Bing X, Song L, Na C, Minghong D, Annuo L. Intracavitary electrocardiogram guidance for placement of peripherally inserted central catheters in premature infants. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e18368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xiao AQ, Sun J, Zhu LH, Liao ZY, Shen P, Zhao LL, Latour JM. Effectiveness of intracavitary electrocardiogram-guided peripherally inserted central catheter tip placement in premature infants: a multicentre pre-post intervention study. Eur J Pediatr. 2020;179:439-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bashir RA, Callejas AM, Osiovich HC, Ting JY. Percutaneously Inserted Central Catheter-Related Pleural Effusion in a Level III Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A 5-Year Review (2008-2012). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2017;41:1234-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sharma D, Farahbakhsh N, Tabatabaii SA. Role of ultrasound for central catheter tip localization in neonates: a review of the current evidence. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:2429-2437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Abdullah BJ, Mohammad N, Sangkar JV, Abd Aziz YF, Gan GG, Goh KY, Benedict I. Incidence of upper limb venous thrombosis associated with peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC). Br J Radiol. 2005;78:596-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sol JJ, van de Loo M, Boerma M, Bergman KA, Donker AE, van der Hoeven MAHBM, Hulzebos CV, Knol R, Djien Liem K, van Lingen RA, Lopriore E, Suijker MH, Vijlbrief DC, Visser R, Veening MA, van Weissenbruch MM, van Ommen CH. NEOnatal Central-venous Line Observational study on Thrombosis (NEOCLOT): evaluation of a national guideline on management of neonatal catheter-related thrombosis. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18:84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Conti GO, Molinari AC, Signorelli SS, Ruggieri M, Grasso A, Ferrante M. Neonatal Systemic Thrombosis: An Updated Overview. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2018;16:499-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sirachainan N, Limrungsikul A, Chuansumrit A, Nuntnarumit P, Thampratankul L, Wangruangsathit S, Sasanakul W, Kadegasem P. Incidences, risk factors and outcomes of neonatal thromboembolism. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31:347-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Saracco P, Bagna R, Gentilomo C, Magarotto M, Viano A, Magnetti F, Giordano P, Luciani M, Molinari AC, Suppiej A, Ramenghi LA, Simioni P; Neonatal Working Group of Registro Italiano Trombosi Infantili (RITI). Clinical Data of Neonatal Systemic Thrombosis. J Pediatr. 2016;171:60-6.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li R, Cao X, Shi T, Xiong L. Application of peripherally inserted central catheters in critically ill newborns experience from a neonatal intensive care unit. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e15837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Monagle P, Chan AKC, Goldenberg NA, Ichord RN, Journeycake JM, Nowak-Göttl U, Vesely SK. Antithrombotic therapy in neonates and children: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e737S-e801S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 933] [Cited by in RCA: 1074] [Article Influence: 76.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Goldsmith R, Chan AK, Paes BA, Bhatt MD; Thrombosis and Hemostasis in Newborns (THiN) Group. Feasibility and safety of enoxaparin whole milligram dosing in premature and term neonates. J Perinatol. 2015;35:852-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Samiee-Zafarghandy S, van den Anker JN, Ben Fadel N. Topical nitroglycerin in neonates with tissue injury: A case report and review of the literature. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19:9-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vivar Del Hoyo P, Sánchez Ruiz P, Ludeña Del Río M, López-Menchero Oliva JC, García Cabezas MÁ. [Use of topical nitroglycerin in newborns with ischaemic injuries after vascular cannulation]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2016;85:155-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Romantsik O, Bruschettini M, Zappettini S, Ramenghi LA, Calevo MG. Heparin for the treatment of thrombosis in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD012185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer review started: April 7, 2020

Specialty type: Nursing

Country/territory of origin: China

Peer review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Alsubai J, Okada S S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Xing YX