Published online Sep 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i18.4252

Peer-review started: February 25, 2020

First decision: July 4, 2020

Revised: July 18, 2020

Accepted: August 14, 2020

Article in press: August 14, 2020

Published online: September 26, 2020

Processing time: 209 Days and 12.1 Hours

Gitelman syndrome (GS) is an unusual, autosomal recessive salt-losing tubulopathy characterized by hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis, hypomagnesemia and hypocalciuria. It is caused by mutations in the solute carrier family 12 member 3 (SLC12A3) gene resulting in disordered function of the thiazide-sensitive NaCl co-transporter. To date, many types of mutations in the SLC12A3 gene have been discovered that trigger different clinical manifestations. Therefore, gene sequencing should be considered before determining the course of treatment for GS patients.

A 55-year-old man was admitted to our department due to hand numbness and fatigue. Laboratory tests after admission showed hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis and renal failure, all of which suggested a diagnosis of GS. Genome sequencing of DNA extracted from the patient’s peripheral blood showed a rare homozygous mutation in the SLC12A3 gene (NM_000339.2: chr16:56903671, Exon4, c.536T>A, p.Val179Asp). This study reports a rare homozygous mutation in SLC12A3 gene of a Chinese patient with GS.

Genetic studies may improve the diagnostic accuracy of Gitelman syndrome and improve genetic counseling for individuals and their families with these types of genetic disorders

Core Tip: In this manuscript, we report a patient with severe hypokalemia who was diagnosed with Gitelman syndrome by genome sequencing. We found a relatively unusual homozygous mutation in the SLC12A3 gene, which has been rarely reported previously. This patient also had elevated creatinine, different to the general Gitelman syndrome, suggesting that some factors, including this type of mutation, may cause renal impairment.

- Citation: Yu RZ, Chen MS. Gitelman syndrome caused by a rare homozygous mutation in the SLC12A3 gene: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(18): 4252-4258

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i18/4252.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i18.4252

Gitelman syndrome (GS), an autosomal recessive disorder caused by a defect in the gene coding for the thiazide-sensitive NaCl cotransporter at the distal tubule, is characterized by hyperreninemic hyperaldosteronism with normal or low blood pressure, hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis, hypomagnesemia and hypocalciuria. It is usually diagnosed in late childhood or adulthood. Symptoms of hypokalemia include fatigue, leg cramps and constipation, but, most critically, slowing of the heart rhythm and even cardiac arrest. Affected individuals may experience episodes of fatigue, dizziness, fainting due to hypotension, muscle weakness, muscle aches, cramps and spasms or even tetany. Symptomatic episodes may also be accompanied by abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, and fever. Seizures may also occur and in some people may be the initial reason they seek medical assistance. Facial paresthesia characterized by numbness or tingling is common. Tingling or numbness of the hands occurs less often. Affected individuals may or may not experience polydipsia, and polyuria including nocturia. When these symptoms do occur they are usually mild. Affected individuals often crave salt or high-salt foods. Some affected adults develop chondrocalcinosis which is thought to be related to hypomagnesemia. Affected joints may be swollen, tender, reddened, and warm to the touch[1].

The SLC12A3 gene, which is located on chromosome 16q13, encodes a transporter that mediates sodium and chloride re-absorption in the distal convoluted tubule of the kidneys[2]. An inactivating mutation in the gene is a recognized diagnostic criterion for GS. GS is usually managed with oral potassium and magnesium supplements, potassium-sparing diuretics, spironolactone or occasionally nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to control the symptoms in these patients[3]. We present a 55-year-old man diagnosed with GS on the basis of his clinical features, laboratory tests and genetic analysis. We illustrate the management of his condition and review the relevant literature.

A 55-year-old man was admitted to the Emergency Department complaining of numbness in his hands and fatigue, without dizziness, vomiting or seizures.

The patient’s symptoms started 12 years ago with recurrent numbness in the upper limbs and fatigue. He was diagnosed with hypokalemia in a local hospital and took potassium supplements intermittently. His symptoms had worsened over the last 4 d.

He had been diagnosed with hepatitis B virus infection.

The patient’s temperature was 37.1 °C, pulse rate was 59 bpm, respiratory rate was 16 breaths/min, blood pressure was 111/88 mmHg, and oxygen saturation in room air was 97%. Physical examination findings were within the reference range.

During the patient’s presentation in the Emergency Department, his serum chemistry revealed severe hypokalemia with a potassium level of 1.99 mmol/L (normal range: 3.50-5.50 mmol/L). In addition to low potassium, his creatinine level was 138.6 μmol/L.

After symptomatic treatment, he was transferred to the Department of Nephrology for further clinical diagnosis and therapy. Laboratory analysis revealed a low potassium level (3.21 mmol/L), normal magnesium (0.93 mmol/L) and increased creatinine level (166.2 μmol/L). In addition, his liver enzyme levels were increased (aspartate aminotransferase 104 U/L and alanine aminotransferase 54 U/L) due to hepatitis B virus infection. Plasma renin activity and aldosterone level during rest periods were elevated at 18.331 ng/mL/h and 244.6 pg/mL, respectively. Hypoproteinemia and dyslipidemia were not detected. Urinalysis revealed protein 2+ and occult blood 2+. Twenty-four-hour urine protein was 828.8 mg. Other serum and urine biochemistry findings are shown in Table 1. An electrocardiogram exhibited left ventricular high voltage and changes in the T wave.

| Variable | Value | Standards |

| Serum parameters | ||

| Potassium | 3.21 mmol/L | 3.5-5.3 |

| Sodium | 139.5 mmol/L | 137.0-147.0 |

| Chlorine | 103.7 mmol/L | 99.0-110.0 |

| Calcium | 2.30 mmol/L | 2.10-2.80 |

| Phosphate | 1.04 mmol/L | 0.85-1.51 |

| Magnesium | 0.93 mmol/L | 0.75-1.02 |

| pH | 7.471 | 7.350-7.450 |

| Bicarbonate | 27.0 mmol/L | 22.0-27.0 |

| Carbon dioxide | 22.2 mmol/L | 24.0-32.0 |

| Albumin | 39.9 g/L | 40.0-55.0 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 102 U/L | 45-105 |

| Creatinine | 166.2μmol/L | 58.0-110.0 |

| Urea | 9.89 mmol/L | 3.2-7.1 |

| 25-hydroxy vitamin D3 | 32.92 ng/mL | 20.0-50.0 |

| PTH | 33.0 pg/mL | 15-65 |

| Lying renin | 23.329 ng/mL/h | 0.100-6.560 |

| Standing renin | 18.331 ng/mL/h | 0.150-2.330 |

| Lying aldosterone | 244.6 pg/mL | 30.0-160.0 |

| Standing aldosterone | 183.0 pg/mL | 70.0-300.0 |

| Urine parameters | ||

| 24 h urine volume | 1600 mL | 500-3000 |

| 24 h urine potassium | 69.6 mmol/24 h | 25.0-100.0 |

| 24 h urine sodium | 129.9 mmol/24 h | 130.0-260.0 |

| 24 h urine chlorine | 138.6 mmol/24 h | 110.0-250.0 |

| 24 h urine calcium | 1.44 mmol/24 h | 2.50-7.50 |

| 24 h urine creatinine | 15.62 mmol/24 h | 8.80-13.26 |

| Urine potassium/creatinine | 3.33 mmol/mmol | 1.53-8.27 |

| Urine sodium/creatinine | 15.91 mmol/mmol | 3.25-22.29 |

| Urine chlorine/creatinine | 15.64 mmol/mmol | 3.95-22.30 |

| Urine calcium/creatinine | 0.11 mmol/mmol | 0.15-0.52 |

| PTH, parathyroid hormone |

A chest computed tomography scan revealed scattered calcifications. On ultrasonography, liver cirrhosis with multiple nodules and no pathology was seen in the spleen, pancreas and gallbladder. A urinary computed tomography scan showed multiple cysts and stones in the kidneys.

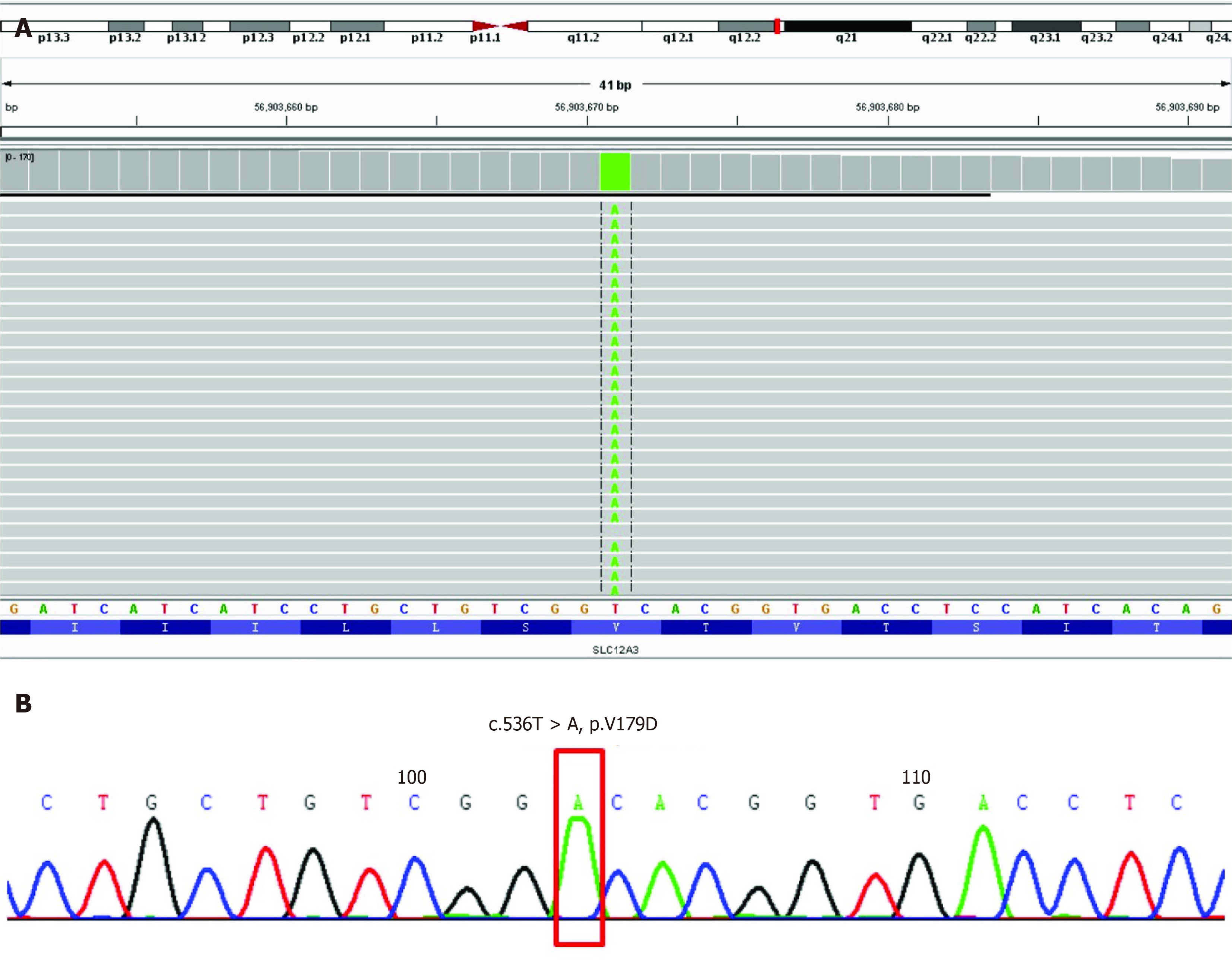

Written informed consent for genetic analysis was obtained from the patient. Total DNA was extracted from peripheral blood for whole genome sequencing (Joingenom Diagnostics, Hangzhou, China). A homozygous mutation T to A at position 536 in exon 4 of SLC12A3 gene (Figure 1) was identified in this patient. This rare mutation caused a Val to Asp substitution, resulting in a missense mutation affecting gene function. A similar novel SLC12A3 pathogenic mutation was reported in a cohort of Chinese patients with GS previously[4].

The patient was successfully treated with potassium chloride sustained-release tablets at a dose of 1 g three times/day. He was discharged from hospital 8 d after admission, and his potassium level was 3.5 mmol/L. He was maintained on potassium 1 g/d and spironolactone 20 mg twice/day. He was also given valsartan for proteinuria and entecavir for hepatitis B virus infection.

After discharge, the patient reported relief of numbness in his hands and fatigue and his serum potassium level remained in the normal range.

GS, also known as familial hypokalemia, is an autosomal recessive tubular disease[5]. The typical clinical manifestations of GS patients are "five low and one high", which means hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypochloremia, low urinary calcium, hypotension, and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) activation[6]. The common clinical manifestations of GS are mostly non-specific, often associated with electrolyte imbalance and increased RAAS activity[7]. Even without long-term oral diuretics and other drugs, vomiting, diarrhea, hypercortisolism, and primary aldosteronism, GS can be diagnosed by clinical manifestations and laboratory tests alone. However, GS is easily misdiagnosed as classic Bartter Syndrome (BS) with analogous clinical features. Some researchers believe it is better to consider BS and GS as a spectrum of disease rather than distinct disorders. The defect in GS involves the distal convoluted tubule while in BS the defect is in the thick ascending limb. Renal salt wasting is more severe and begins earlier in life in BS than in GS with manifestations rarely occurring in the neonatal period[8].

With the development of genetic testing technology, more cases of hypokalemia have been diagnosed as GS. The pathogenesis of GS is related to a mutation in the SLC12A3 gene. At present, more than 400 mutation sites in SLC12A3 have been found[9]. These mutations include nonsense, missense, frameshift, deletion and insertion mutations. Heterozygous mutations are more common than homozygous mutations. Approximately 45% are compound heterozygous mutations occurring at two sites or more. However, the number of mutation sites showed no obvious correlation with clinical manifestations[4]. The SLC12A3 gene encodes a thiazide diuretic-sensitive NaCl co-transporter consisting of 12 transmembrane domains with both the amino terminus and the carboxy terminus inside the cell[10]. Mutations in the SLC12A3 gene cause damage to the renal tubular Na+/Cl- transport function, resulting in a decrease in Na+ and Cl- re-absorption in the distal collecting tube, leading to loss of NaCl, hypovolemia, hypotension, and metabolic alkalosis, followed by rising levels of renin and aldosterone. Increased reabsorption of Na+ through Na+ channels in epithelial cells on the cortical collecting duct is beneficial to the secretion of H+ and K+[11]. Abnormal Na+/Cl- transport can attenuate the hyperpolarization of Cl- inside the cells, increase Ca2+ re-absorption, and reduce levels of urinary calcium as seen in our case[12].

The mechanism underlying GS hypomagnesemia is unclear. It may be related to the down-regulation of Mg2+ M6 transient receptor potential channel protein on the apical membrane of distal convoluted tubules, resulting in increased renal magnesium excretion. The expression of M6 transient receptor potential channel protein in the intestine is down-regulated, the absorption of Mg2+ in the intestine is reduced, and eventually the blood magnesium is decreased[13]. Another reason for the decrease in blood Mg2+ may be acceleration of Mg2+/Na+ exchange on the luminal side caused by the increase in Na+ re-absorption, which leads to increased magnesium in urine and decreased magnesium in blood[14]. A total of 83.3% GS patients have hypomagnesemia, and only a few of have normal blood magnesium. GS patients with normal magnesium may make up a subtype accounting for 8% to 22% of cases reported in one study[15,16]. Jiang et al[14] observed 25 patients with GS and found that blood potassium in patients with normal magnesium (7/25) was slightly higher than those with hypomagnesemia (18/25). As hypomagnesemia can induce a further decrease in serum potassium, hypokalemia, hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis and RAAS activation are less severe in GS patients with normal magnesium than in GS patients with hypomagnesemia[15].

GS treatment mainly involves correcting disorders of electrolytes and metabolism, thereby alleviating clinical symptoms. For better efficacy, potassium supplementation should be combined with magnesium, aldosterone receptor antagonists, renin-angiotensin system inhibitors (angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers) and other drugs. Aldosterone receptor antagonists compound the renal salt wasting and should thus be started cautiously to avoid hypotension. Concomitant salt supplementation should be considered. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers can also aggravate renal sodium wasting and increase the risk of symptomatic hypovolemia; these agents should be stopped in the case of acute, salt-losing complications, such as vomiting or diarrhea[1]. It is very important to facilitate patient education which is an essential component of management. Patients are encouraged to eat more foods containing sodium chloride, potassium and magnesium as part of their diet. It is imperative that patients are aware of the adverse reactions of therapeutic drugs, especially gastrointestinal irritation caused by potassium chloride. In addition, there is a need to educate patients about what to do in the case of an emergency. Patients can exercise, but must pay special attention when participating in high-intensity and competitive sports, that can cause salt loss through sweating. During excessive sweating, diarrhea or vomiting, it is necessary to replenish electrolytes promptly to avoid serious complications[17].

Our patient had middle-aged GS onset, and the clinical manifestations were limb weakness and convulsions, but no hypertension. He had a family history of the condition. Laboratory examinations showed hypokalemia, normal blood magnesium level, metabolic alkalosis, hypocalciuria, proteinuria and RAAS activation. Through genome sequencing, the mutation c.536T > A (p.Val179Asp) of SLC12A3 gene was identified which supported our diagnosis of GS. This type of mutation is relatively rare. At present, few studies have reported cases of GS with proteinuria. Proteinuria might develop due to abnormalities of the glomerular basement membrane. Chronic kidney disease may develop in GS patients due to either chronic hypokalemia, which is associated with tubulointerstitial nephritis, tubule vacuolization, and cystic changes, or volume depletion and increased renin-angiotensin-aldosterone, which may contribute to renal damage and fibrosis. This patient also showed elevated creatinine, suggesting glomerular damage. He had hepatitis B virus infection; thus, we initially attributed the increase in creatinine to hepatitis B nephropathy. However, the possibility of other primary kidney diseases could not be eliminated. Unfortunately, the patient declined renal biopsy; therefore, the cause and progress of renal dysfunction required further investigation. Excluding other causes of renal impairment, and whether the SLC12A3 gene mutation in GS patients affects podocyte function have not been reported and further supporting research is needed.

We report the case of a rare homozygous mutation in the SLC12A3 gene in a Chinese patient with GS diagnosed by whole-exome sequencing, which showed that genome sequencing is a useful method for identifying genes involved in human genetic diseases.

We are grateful to the patient and his family for their willingness to participate in this study.

| 1. | Blanchard A, Bockenhauer D, Bolignano D, Calò LA, Cosyns E, Devuyst O, Ellison DH, Karet Frankl FE, Knoers NV, Konrad M, Lin SH, Vargas-Poussou R. Gitelman syndrome: consensus and guidance from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2017;91:24-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Simon DB, Bindra RS, Mansfield TA, Nelson-Williams C, Mendonca E, Stone R, Schurman S, Nayir A, Alpay H, Bakkaloglu A, Rodriguez-Soriano J, Morales JM, Sanjad SA, Taylor CM, Pilz D, Brem A, Trachtman H, Griswold W, Richard GA, John E, Lifton RP. Mutations in the chloride channel gene, CLCNKB, cause Bartter's syndrome type III. Nat Genet. 1997;17:171-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 666] [Cited by in RCA: 611] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Peters M, Jeck N, Reinalter S, Leonhardt A, Tönshoff B, Klaus G Gü, Konrad M, Seyberth HW. Clinical presentation of genetically defined patients with hypokalemic salt-losing tubulopathies. Am J Med. 2002;112:183-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ma J, Ren H, Lin L, Zhang C, Wang Z, Xie J, Shen PY, Zhang W, Wang W, Chen XN, Chen N. Genetic Features of Chinese Patients with Gitelman Syndrome: Sixteen Novel SLC12A3 Mutations Identified in a New Cohort. Am J Nephrol. 2016;44:113-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Simon DB, Nelson-Williams C, Bia MJ, Ellison D, Karet FE, Molina AM, Vaara I, Iwata F, Cushner HM, Koolen M, Gainza FJ, Gitleman HJ, Lifton RP. Gitelman's variant of Bartter's syndrome, inherited hypokalaemic alkalosis, is caused by mutations in the thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter. Nat Genet. 1996;12:24-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 889] [Cited by in RCA: 834] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ren H, Qin L, Wang W, Ma J, Zhang W, Shen PY, Shi H, Li X, Chen N. Abnormal glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity in Chinese patients with Gitelman syndrome. Am J Nephrol. 2013;37:152-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Al Shibli A, Narchi H. Bartter and Gitelman syndromes: Spectrum of clinical manifestations caused by different mutations. World J Methodol. 2015;5:55-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Vilela LAP, Almeida MQ. Diagnosis and management of primary aldosteronism. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2017;61:305-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Luo J, Yang X, Liang J, Li W. A pedigree analysis of two homozygous mutant Gitelman syndrome cases. Endocr J. 2015;62:29-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vargas-Poussou R, Dahan K, Kahila D, Venisse A, Riveira-Munoz E, Debaix H, Grisart B, Bridoux F, Unwin R, Moulin B, Haymann JP, Vantyghem MC, Rigothier C, Dussol B, Godin M, Nivet H, Dubourg L, Tack I, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Houillier P, Blanchard A, Devuyst O, Jeunemaitre X. Spectrum of mutations in Gitelman syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:693-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Groenestege WM, Thébault S, van der Wijst J, van den Berg D, Janssen R, Tejpar S, van den Heuvel LP, van Cutsem E, Hoenderop JG, Knoers NV, Bindels RJ. Impaired basolateral sorting of pro-EGF causes isolated recessive renal hypomagnesemia. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2260-2267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Kurtz I. Molecular pathogenesis of Bartter's and Gitelman's syndromes. Kidney Int. 1998;54:1396-1410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nijenhuis T, Vallon V, van der Kemp AW, Loffing J, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. Enhanced passive Ca2+ reabsorption and reduced Mg2+ channel abundance explains thiazide-induced hypocalciuria and hypomagnesemia. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1651-1658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 14. | Jiang L, Chen C, Yuan T, Qin Y, Hu M, Li X, Xing X, Lee X, Nie M, Chen L. Clinical severity of Gitelman syndrome determined by serum magnesium. Am J Nephrol. 2014;39:357-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu T, Wang C, Lu J, Zhao X, Lang Y, Shao L. Genotype/Phenotype Analysis in 67 Chinese Patients with Gitelman's Syndrome. Am J Nephrol. 2016;44:159-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang F, Shi C, Cui Y, Li C, Tong A. Mutation profile and treatment of Gitelman syndrome in Chinese patients. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2017;21:293-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Elbouajaji K, Blanchier D, Pourrat O, Sarreau M. [Management of Gitelman syndrome during pregnancy reporting 12 cases]. Nephrol Ther. 2018;14:536-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Usta IM S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Xing YX