Published online Feb 16, 2015. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i2.186

Peer-review started: June 23, 2014

First decision: October 14, 2014

Revised: October 28, 2014

Accepted: November 19, 2014

Article in press: November 19, 2014

Published online: February 16, 2015

Processing time: 227 Days and 15.7 Hours

Diffuse large B cell primary hepatic lymphoma is a rare disease with limited available information regarding treatment strategy. Although the liver contains lymphoid tissue and is an important site for lymphocytes activation, primary hepatic lymphoma is rare. Host factors make the liver a poor environment for malignant lymphoma development. Its coexistence with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection increases morbidity and mortality risks. Additionally, jaundice increases chances of developing adverse effects from chemotherapy. Here, we report a case of diffuse large B cell primary hepatic lymphoma in a 32-year-old HIV positive man. Due to elevated liver enzyme levels and jaundice, the patient was initially treated with an R-DHAP regimen, which was replaced with an R-CHOP regimen. Restaging images with a positron emission tomography scan after the latest chemotherapy cycle confirmed remission. This is the first report of complete remission of primary hepatic diffuse large B cell lymphoma in an HIV positive patient in the English literature.

Core tip: There are limited reports related to successful management of primary hepatic lymphoma in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients. This case report is not only considered as the first report of complete remission of primary hepatic diffuse large B cell lymphoma in an HIV positive patient in the English literature, but also describes the use of R-DHAP as an induction regimen in the setting of significant impaired liver function and severe immunocompromised status. The use of R-DHAP as an induction regimen in management of primary hepatic lymphoma in HIV patients was never reported.

- Citation: Widjaja D, AlShelleh M, Daniel M, Skaradinskiy Y. Complete remission of primary hepatic lymphoma in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. World J Clin Cases 2015; 3(2): 186-190

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v3/i2/186.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v3.i2.186

Primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL) is a rare disease associated with immunodeficiency diseases and chronic viral hepatitis. From 1981 to 2003, only 358 cases of primary hepatic lymphoma were reported[1]. Data surrounding disease managements in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is lacking. Here, we present a case of an HIV positive man whose PHL subsided into complete remission after chemotherapy.

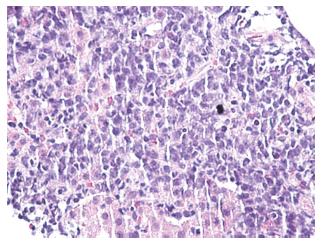

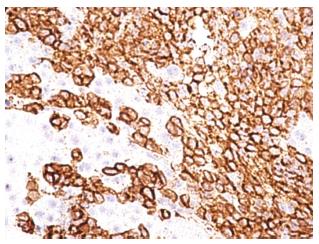

A 32-year-old man with no known significant chronic medical problems was admitted to the hospital due to severe right upper quadrant abdominal pain, fever, night sweats, and unintentional weight loss. There was no history of recent heavy alcohol consumption. The patient appeared jaundiced and had a tender and firm hepatomegaly with a liver span of 19 cm. The lymph node was not enlarged. An abdominal ultrasound revealed multiple small hypoechoic lesions throughout the liver, common bile duct of 3.2 mm and normal gallbladder without gallstones. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast revealed hepatomegaly with multiple small low attenuation nodules throughout the liver parenchyma, normal common bile duct and small ascites in the pelvis (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen with intravenous contrast confirmed CT scan findings. All imaging studies showed no extrahepatic lymphadenopathies. A liver biopsy of lesions revealed diffuse large B cell lymphoma with non-specific lobular hepatitis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical stains of the liver specimen revealed CD20+, CD79+, CD79a+, CD4-, and CD3- cells (Figure 3). The patient also tested positive for HIV infection. Tests for hepatitis B and C were negative. Additional tests results are shown in Table 1.

| Prior tothe 1st | Prior tothe 2nd | Prior tothe 3rd | Prior tothe 4th | Prior tothe 5th | Prior tothe 6th | Prior tothe 7th | Prior tothe 8th | 6 mo post chemotherapy | |

| Hgb (g/dL) | 11.9 | 11.3 | 11.1 | 11.3 | 12 | 12.5 | 11.8 | 12.3 | 14.6 |

| Platelet count (× 103 /uL) | 107 | 95 | 107 | 34 | 169 | 132 | 60 | 78 | 70 |

| WBC (× 103/uL) | 5.9 | 10.6 | 1.9 | 11.9 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 5.9 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.5 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 4.9 |

| Serum AST (unit/L) | 529 | 38 | 26 | 26 | 31 | 23 | 31 | 26 | 24 |

| Serum ALT (unit/L) | 270 | 43 | 37 | 30 | 28 | 27 | 39 | 31 | 30 |

| Serum alkaline phosphatase (unit/L) | 1686 | 442 | 146 | 210 | 1025 | 1586 | 1454 | 190 | 117 |

| Serum GGT (unit/L) | 872 | - | - | - | - | 149 | - | - | - |

| Serum LDH (unit/L) | 1838 | 313 | - | 331 | 326 | 263 | - | 148 | 124 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 9.7 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| CD4 lymphocyte count (/mm3) | 155 | 651 | - | 265 | - | - | 173 | - | 729 |

| HIV viral load (copies/mL) | 485127 | 81 | - | < 75 | - | - | < 75 | - | < 75 |

The patient was diagnosed with Stage 1BE primary liver large B cell lymphoma, and started on anti retroviral therapy along with chemotherapy during in-patient care. The initial anti retroviral medications were efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir. On the 7th day of the treatment, efavirenz was changed to raltegravir due to the presence of G190A mutation on HIV genotyping testing which confers resistance to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor mutation. Eight cycles of chemotherapy were administered together with anti retroviral therapy. In view of elevated liver enzymes and jaundice, chemotherapy with a platinum based regimen (R-DHAP) was initiated. The regimen of this first cycle consisted of 1.5 mg/kg of oral prednisone, 375 mg/m2 of rituximab, 100 mg/m2 of cisplatin, and 2000 mg/m2 of cytarabine. As the co-administration of cisplatin and tenofovir might have increased his risk of toxicity to the kidney proximal tubule, serum creatinine was monitored closely. His serum creatinine levels were always less than 1 mg/dL and the calculated creatinine clearance was maintained at the level of 77 mL/min per 1.73 m2. Nine days after starting the first chemotherapy cycle, he developed significant thrombocytopenia (nadir of 10000 cells/uL) and neutropenia (nadir of 300/uL). When platelet count was 10000/uL, the patient had an episode of epistaxis which was controlled after platelets transfusion. He did not develop fever during the episode of neutropenia. Filgrastim was given for 3 d when neutropenia was 300/uL. Upon the completion of first cycle of chemotherapy, the patient remained afebrile and became less jaundiced. Chemotherapy normalized liver enzymes and bilirubin (Table 1). Next, a CHOP regimen containing cyclophosphamide (600 mg/m2), adriamycin (50 mg/m2), vincristine (1.1 mg/m2), and prednisone was administered. Rituximab (375 mg/m2) was added to the CHOP regimen to start a third cycle of chemotherapy administered every 3 wk. As there was no known significant drug-drug interaction between the R-CHOP regimen and the anti retroviral regimen (tenofovir, emtricitabine and raltegravir), all medications were given according to the standard doses. After the second cycle, the patient remained anicteric with a body weight improvement of 5 kg from baseline. A CT with positron emission tomography (PET) scan performed after the 4th cycle of chemotherapy showed that the liver had reduced in size from 19.5 cm (prior to treatment) to 16.5 cm without evidence of hypermetabolic foci in the neck, chest, abdomen, or pelvis. Re-staging images with CT-PET after the 6th cycle revealed normal uptake within liver, spleen, adrenal glands, renal cortices, and the collecting system. A CT-PET scan at 5 and 11 mo after the last cycle confirmed remission (Figure 4). He is still in remission 19 mo after the treatment. During the chemotherapy, the CD4 count had improved and HIV viral loads were always undetectable (Table 1).

Fifty thousand incident cases of lymphoid neoplasms and 19000 related deaths occurred in the United States in 2005[2]. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtype and accounts for approximately 23% of all cases[3]. Chronic hepatitis C and hepatitis B and autoimmune diseases increase the risk of PHL[4,5]. Although the liver contains lymphoid tissue and is an important site for lymphocytes activation[6], PHL is rare. Host factors make the liver a poor environment for malignant lymphoma development[4,7].

Criteria for establishing the diagnosis of PHL include clinical, histopathological, and radiological findings. Lei et al[8] listed the following criteria to establish diagnosis: (1) signs and symptoms related to liver involvement at presentation including laboratory abnormalities and right upper quadrant mass or pain; (2) absence of both palpable adenopathy at presentation and radiologically evident distant lymphadenopathy; and (3) absence of leukemia on a peripheral smear.

A report from Lei[9] showed that among 90 patients with PHL, the most frequent presenting symptoms were upper abdominal pain or discomfort (56%), weight loss (40%), and fever (22%), which occasionally mimic pyogenic liver abscess. Other symptoms included fatigue (13%), nausea and vomiting (12%), anorexia (8%), night sweats (8%), hemorrhagic diathesis (2%), dysphagia (2%), and rarely, immune thrombocytopenic purpura (1%) and hepatic encephalopathy (1%). In this particular report, 10% of patients were diagnosed incidentally without preceding symptoms. Physical examinations frequently revealed a modest hepatomegaly (82%), but jaundice infrequently presented only as a late manifestation of disease progression or related to underlying cirrhosis (13%)[9]. Lactate dehydrogenase and alkaline phosphatase are sometimes elevated[10]. Alpha-fetoprotein and carcinoembryonic antigen are often normal[4,10]. Radiologically, the presentation of multiple well-defined liver masses is more common than single lesions or diffuse hepatic involvement[11]. On ultrasound imaging, PHL is usually hypoechoic relative to a normal liver. CT scans of PHL usually show hypoattenuating lesions[4,11]. FDG-PET studies are extremely useful in evaluating treatment responses in PHL[12]. Histologically, primary diffuse large B cell lymphoma shows demarcated tumors with no intrasinusoidal invasion, atrophic reactive lymph follicles, and tests positive for the following antigens: CD10, Bcl2, Bcl6, MUM1, and CD25[5].

The United States National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends managing diffuse large B cell lymphoma with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP protocol)[13]. Other regimens include CODOX-M/IVAC (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, high dose methotrexate alternating with ifosfamide, etoposide, high dose cytarabine with or without rituximab), dose adjusted EPOCH (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin), dose adjusted EPOCH with rituximab, CDE (cyclophosphosphamide, doxorubicin and etoposide), CDE with rituximab, and hyperCVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and dexamethasone alternating with high-dose methotrexate, and cytarabine with or without rituximab)[13]. Serrano-Navarro et al[1] highlighted a patient with PHL who developed complete response to R-CHOP treatment regimen, remaining symptom free for more than two years. Others also reported complete response to R-CHOP in non-HIV infected patients with diffuse large B cell type primary hepatic lymphoma[14-17]. Besides the R-CHOP regimen, a regimen contains rituximab, dexamethasone, high dose cytarabine, and cisplatin (R-DHAP) has been used as a salvage therapy in patients with CD20+ diffuse large B cell lymphoma who develop first time relapse or failure with first line therapy[18]. In addition, R-DHAP, given as remission induction chemotherapy, improved progression free survival and failure free survival in patients with aggressive CD20+ non-Hodgkin lymphomas[19].

In an article in French literature, Walter et al[17] reported the only favorable response to an R-CHOP treatment regimen for diffuse large B cell type PHL in an HIV infected patient. The case report described a 34-year-old man whose abdomen CT scan showed multiple liver masses, the largest of which was 14 cm. After four cycles of R-CHOP treatment, the masses markedly regressed with only a residual 5 cm hypodense lesion. Our patient developed complete remission without residual hepatic lesions. To our knowledge, this is the first report of PHL treatment in an AIDS patient that resulted in a complete response. After initial treatment with an R-DHAP regimen, serum levels of liver enzymes and bilirubin, very important in preventing the prolonged half-life of cyclophosphamide and neurotoxicity of vincristine[20], decreased. This may have facilitated further remission from the R-CHOP regimen. Further studies in HIV positive patients may confirm these findings.

A 32-year-old man with recent history of unintentional weight loss presented with right upper quadrant pain.

Patient appeared jaundiced and had a tender and firm hepatomegaly with a liver span of 19 cm.

Acute ascending cholangitis, alcoholic hepatitis and infiltrative liver disease.

WBC 5.9 K/μL; ALT 270 unit/L; AST 529 unit/L; serum alkaline phosphatase 1686 unit/L; serum GGT 872 unit/L; serum total bilirubin 9.7 mg/dL; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) viral load 485 K copies/mL.

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast revealed hepatomegaly with multiple small low attenuation nodules throughout the liver parenchyma, normal common bile duct and small ascites in the pelvis. Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed CT scan findings.

A liver biopsy of lesions revealed diffuse large B cell lymphoma with non-specific lobular hepatitis. Immunohistochemical stains of the liver specimen revealed CD20+, CD79+, CD79a+, CD4-, and CD3- cells.

Eight cycles of chemotherapy were administered. R-DHAP regimen was given in the first cycle. CHOP regimen was started in the second cycle. R-CHOP regimen was started in the third cycle.

In view of elevated liver enzymes and jaundice, chemotherapy with a platinum based regimen (R-DHAP) was given in the first cycle of chemotherapy. Upon completion of the first cycle, the patient became less jaundiced.

Cluster of differentiation (CD) of immunohistochemical stain is referred to a group of antibodies recognizing an antigen. For example, the T-helper cell antigen is called CD4 antigen and the various antibodies reacting with this antigen are called CD4 antibodies.

This case report is not only considered as the first report of complete remission of primary hepatic diffuse large B cell lymphoma in an HIV positive patient in the English literature, but also describes the use of R-DHAP as an induction regimen in the setting of significant impaired liver function and severe immunocompromised status. The use of R-DHAP as an induction regimen in management of primary hepatic lymphoma in HIV patients was never been reported.

This case report well written overall.

| 1. | Serrano-Navarro I, Rodríguez-López JF, Navas-Espejo R, Pérez-Jacoiste MA, Martínez-González MA, Grande C, Prieto S. [Primary hepatic lymphoma - favorable outcome with chemotherapy plus rituximab]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2008;100:724-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A, Feuer EJ, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:10-30. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Morton LM, Turner JJ, Cerhan JR, Linet MS, Treseler PA, Clarke CA, Jack A, Cozen W, Maynadié M, Spinelli JJ. Proposed classification of lymphoid neoplasms for epidemiologic research from the Pathology Working Group of the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium (InterLymph). Blood. 2007;110:695-708. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Yang XW, Tan WF, Yu WL, Shi S, Wang Y, Zhang YL, Zhang YJ, Wu MC. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of primary hepatic lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:6016-6019. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Kikuma K, Watanabe J, Oshiro Y, Shimogama T, Honda Y, Okamura S, Higaki K, Uike N, Soda T, Momosaki S. Etiological factors in primary hepatic B-cell lymphoma. Virchows Arch. 2012;460:379-387. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Crispe IN. The liver as a lymphoid organ. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:147-163. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Maes M, Depardieu C, Dargent JL, Hermans M, Verhaeghe JL, Delabie J, Pittaluga S, Troufléau P, Verhest A, De Wolf-Peeters C. Primary low-grade B-cell lymphoma of MALT-type occurring in the liver: a study of two cases. J Hepatol. 1997;27:922-927. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Lei KI, Chow JH, Johnson PJ. Aggressive primary hepatic lymphoma in Chinese patients. Presentation, pathologic features, and outcome. Cancer. 1995;76:1336-1343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lei KI. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the liver. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;29:293-299. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Page RD, Romaguera JE, Osborne B, Medeiros LJ, Rodriguez J, North L, Sanz-Rodriguez C, Cabanillas F. Primary hepatic lymphoma: favorable outcome after combination chemotherapy. Cancer. 2001;92:2023-2029. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Elsayes KM, Menias CO, Willatt JM, Pandya A, Wiggins M, Platt J. Primary hepatic lymphoma: imaging findings. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2009;53:373-379. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Seshadri N, Ananthasivan R, Kavindran R, Srikanth G, Chandra S. Primary hepatic (extranodal) lymphoma: utility of [(18)F]fluorodeoxyglucose-PET/CT. Cancer Imaging. 2010;10:194-197. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Zelenetz AD, Wierda WG, Abramson JS, Advani RH, Andreadis CB, Bartlett N, Bellam N, Byrd JC, Czuczman MS, Fayad L. NCCN Guidelines(R) Updates. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:xxxii-xxxvi. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Asagi A, Miyake Y, Ando M, Yasuhara H, Matsumoto K, Takahara M, Kawai D, Kaji E, Toyokawa T, Onishi T. [Case of primary malignant lymphoma of the liver treated by R-CHOP therapy]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2009;106:389-396. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Hiramoto K, Kuroki M, Shoji H, Matsumura Y, Miura A, Kikuchi Y, Hirakawa H, Kimura J, Matsuda M. [A case of primary hepato-biliary malignant lymphoma effectively treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2010;37:1345-1348. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Zafar MS, Aggarwal S, Bhalla S. Complete response to chemotherapy in primary hepatic lymphoma. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012;8:114-116. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Walter T, Béziat C, Miailhes P, Scalone O, Lebouché B, Trepo C. [Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the liver in HIV infected patient: case-report]. Rev Med Interne. 2004;25:596-600. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Gisselbrecht C, Glass B, Mounier N, Singh Gill D, Linch DC, Trneny M, Bosly A, Ketterer N, Shpilberg O, Hagberg H. Salvage regimens with autologous transplantation for relapsed large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4184-4190. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Vellenga E, van Putten WL, van ‘t Veer MB, Zijlstra JM, Fibbe WE, van Oers MH, Verdonck LF, Wijermans PW, van Imhoff GW, Lugtenburg PJ. Rituximab improves the treatment results of DHAP-VIM-DHAP and ASCT in relapsed/progressive aggressive CD20+ NHL: a prospective randomized HOVON trial. Blood. 2008;111:537-543. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Donelli MG, Zucchetti M, Munzone E, D’Incalci M, Crosignani A. Pharmacokinetics of anticancer agents in patients with impaired liver function. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:33-46. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewer: Akbulut S, Alsolaiman MM, Boffano P S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/