Published online Feb 26, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i6.118460

Revised: January 18, 2026

Accepted: January 26, 2026

Published online: February 26, 2026

Processing time: 42 Days and 9.8 Hours

The protein thioredoxin-1 (TRX-1) has anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects, and it has been related to the regulation of ageing and different diseases. TRX-1 in periodontitis has been scarcely studied, and the results in humans and in mice are contradictory. In three small studies with humans (the highest with 96 subjects), it was found that patients with periodontitis, compared to periodontally healthy subjects, showed a higher expression of TRX-1 or of the TRX-1 gene in saliva. However, in one study with mice, it was found that mice with periodontitis, compared to periodontally healthy mice, showed a lower ex

To explore the possible association of salivary TRX-1 concentrations with periodontitis and its severity, and of determining the capability of salivary TRX-1 con

Salivary TRX-1 concentrations were measured in subjects with and without periodontitis in this observational and prospective study. Criteria to establish periodontal health were the nonexistence, or existence in less than 10% of sites, of bleeding on probing, and the nonexistence of interproximal attachment and bone loss. Criteria to establish localized gingivitis were the existence of bleeding between 10%-30% of sites, and the nonexistence of interproximal attachment and bone loss. Criteria to establish periodontitis were the existence of interproximal attachment or bone loss. We carried out a multivariate logistic regression analysis to determine the variables associated with periodontitis, a correlation analysis to determine the possible association between salivary TRX-1 concentrations and periodontitis severity, and a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis to determine the capability of salivary TRX-1 concentrations to predict the diagnosis of periodontitis.

A total of 144 subjects (58 with periodontitis and 86 without periodontitis) were included. Low salivary TRX-1 concentrations showed an association with periodontitis (P = 0.04) according to regression analysis, an association with periodontitis severity (rho = -0.47; P < 0.001) according to correlation analysis, and an area under curve of 75% (95%CI: 67%-82%; P < 0.001) for periodontitis diagnosis according to ROC analysis.

Novel findings of this study were the association of low salivary TRX-1 concentrations with periodontitis and its severity, and the capacity of salivary TRX-1 concentrations to help in the periodontitis diagnosis.

Core Tip: The protein thioredoxin-1 (TRX-1) has anti-oxidative effects and is involved in senescence, aging and different diseases. Salivary levels of TRX-1 in patients with periodontitis have not been explored. Novel findings of this study were the association of low salivary TRX-1 concentrations with periodontitis and its severity, and the capacity of salivary TRX-1 concentrations to help in the diagnosis of periodontitis.

- Citation: Lorente L, Hernández Marrero E, Abreu-Gonzalez P, Lorente Martín AD, Lorente Martín M, Marrero González MJ, Hernández Marrero C, Hernández Marrero O, Jiménez A, Hernández Padilla CM. Low salivary thioredoxin-1 levels in periodontitis. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(6): 118460

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i6/118460.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i6.118460

Periodontitis consists of a chronic inflammatory disease of periodontal tissue that could motivate tooth loss. It has a high prevalence, affecting up to 90% of the subjects[1], and severely up to 15% of humans[2]. Different mechanisms are in

The thioredoxin system has an important role in oxidation, inflammation, apoptosis, senescence and aging; in addition, the thioredoxin system has been recently studied in different diseases such as inflammatory illnesses, neurodegenerative diseases, ischemic stroke, cancer, diabetes and chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular diseases[6-11]. Besides, the thioredoxin system could also play a role in periodontitis[12,13].

The thioredoxin system involves the thioredoxin protein (TRX), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), the thioredoxin reductase (TrxR), and thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP).

In mammalian cells, three TRX isoforms have been identified: Cytosolic TRX (TRX-1), mitochondrial TRX (TRX-2), and spermatozoa Trx (SpTRX). TRX-1 is the most studied TRX. TRX-1 has two forms (oxidized inactive form and reduced active form). The reduced active form of TRX-1 has anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects.

NADPH oxidase is involved in the production of reactive oxidative species (ROS) because it catalyzes the oxidation of NADPH to NADP+ by transferring one electron from NADPH to oxygen, and subsequently NADP+ and ROS appear (NADPH + O2 = NADP+ + O2-). In addition, NADPH could also donate electrons to TrxR; afterwards TrxR transfers these electrons to oxidized inactive TRX-1, resulting in reduced active TRX-1 and NADP+ (NADPH + TRX-1 oxidized = NADP+ + TRX-1 reduced). Thus, TrxR facilitates this reaction and the appearance of the active and reduced TRX-1 form by the action of TrxR and NADPH axis.

TXNIP blocks active TRX-1 because it binds with the active reduced TRX-1 form and blocks the reactivation of TRX-1 by blocking the TrxR and NADPH axis. Thus, TXNIP contributes to oxidation, apoptosis, inflammation and senescence.

The antioxidant effect of TRX-1 consists of reversing the oxidation of oxidized proteins, neutralizing ROS via per

One antioxidant effect of TRX-1 consists of the reduced active form of TRX-1 transferring electrons to oxidized pro

Another antioxidant effect of TRX-1 consists of transferring electrons to peroxiredoxins (Prx). Therefore, Prx is reduced (appearing as the reduced active Prx form) and TRX-1 appears in its oxidized inactive form. Then, reduced Prx transfers those electrons to neutralize ROS such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Reduced Prx transfers electrons to H2O2, resulting in the formation of water (H2O) through different reactions (H2O2 + 2H+ + 2e- = 2 H2O or 2 H2O2 = 2 H2O + O2). Again, oxidized inactive TRX-1 is transformed into the reduced active TRX-1 form by the action of TrxR and NADPH.

Another antioxidant effect of TRX-1 consists of producing redox signals to activate different endogenous antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPX) and catalase (CAT)[14-16].

The anti-apoptotic effects of TRX-1 consist of inhibiting caspase-3, caspase-9, pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins, and pro-apoptotic p53 protein.

The anti-inflammatory effects of TRX-1 consists of inhibiting nuclear factor kappa B and therefore inhibiting inter

All these effects of reduced active TRX-1 form, including anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic actions make TRX1 play an important role in senescence, aging and different diseases[6-11]. Downregulation of active TRX-1 increases oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis. Thus, the administration of TRX-1 agonists, TrxR agonists and TXNIP inhibitors may be beneficial in age-associated diseases. However, the administration of TRX-1 antagonists, TrxR antagonists and TXNIP agonists might help in anticancer treatments to hinder tumor progression[6-11].

TRX-1 in periodontitis has been scarcely studied, and the results in humans[17-19] and in mice are contradictory. In three small studies with humans (the highest with 96 subjects in the study by Toczewska et al[19]), it was found that patients with periodontitis, compared to periodontally healthy subjects, showed a higher expression of TRX-1 or the TRX-1 gene in saliva[17-19]. However, in one study with mice, it was found that mice with periodontitis compared to periodontally healthy mice showed a lower expression of TRX-1 in periodontal tissues[16]. In addition, in the study by Wu et al[16], it was found that the administration of recombinant human TRX-1 (rhTRX-1) restored reduced TRX-1 expression, decreased ROS generation and promoted the alveolar bone repair in mice with periodontitis.

Thus, take into account that oxidation, inflammation, and tissue degradation are involved in periodontitis, that TRX-1 could modulate all these pathways[12,13], and the findings in the study by Wu et al[16] in mice with periodontitis (mice with periodontitis showed a lower expression of TRX-1, and that the administration TRX-1 decreased ROS generation and promoted alveolar bone repair), we hypothesize that TRX-1 could play a protective role in human periodontitis.

We conducted this study with the aim of comparing salivary TRX-1 concentrations in subjects with and without periodontitis in a larger sample size study, exploring the possible association of salivary TRX-1 concentrations with periodontitis and its severity, and determining the capability of salivary TRX-1 concentrations to predict the diagnosis of periodontitis.

This prospective and observational study was carried out at the Clínica Dental Cándido (La Laguna, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain). The study was previously approved by the clinical research ethics committee of the Hospital Uni

We included subjects without signs of periodontitis (with periodontal health or only localized gingivitis in < 30% of sites) and subjects with periodontitis (presence of periodontal tissue loss). We used current internationally accepted criteria for the diagnosis of periodontitis and for the severity classification of periodontitis[20]. We excluded subjects younger than 18 years.

Criteria to establish periodontal health were the nonexistence, or existence in less than 10% of sites, of bleeding on probing, and the nonexistence of interproximal attachment and bone loss.

Criteria to establish localized gingivitis were the existence of bleeding between 10%-30% of sites, and the nonexistence of interproximal attachment and bone loss.

Criteria to establish periodontitis were the existence of interproximal attachment or bone loss. Criteria to establish periodontitis severity were the following: (1) Interproximal clinical attachment loss < 3 mm (stage I), between 3-4 mm (stage II) or loss ≥ 5 mm (stages III or IV); (2) Radiographic bone loss in the coronal third < 15% (stage I), in the coronal third between 15%-33% (stage II) or in the middle or apical third (stages III or IV); and (3) Tooth loss of none (stage I), between 1-4 (stage II) or ≥ 5 teeth (stage III).

Consumption of coffee, tea, tobacco, drugs and alcohol was recorded. Also, sex, age, body mass index (BMI) (kg/m²) and the existence of obesity (defined as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m²). In addition, the personal history of diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, arterial hypertension, cardiovascular disease, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, treatment with methotrexate (at a dose for rheumatoid arthritis), oral cancer, immunosuppressive therapy, radiotherapy was also registered, as well as dental hygiene.

The technique of Navazesh was used to obtain samples of whole and non-stimulated saliva[21]. We took saliva samples in the morning (8 am to 10 am) to reduce potential alterations due to circadian rhythm on salivary biomarker concentrations. The subjects did not brush their teeth, smoke or drink during the 2 hours before sample collection. They rinsed the mouth with 10 mL of deionized water three times. Afterwards, they remained seated for 30 minutes, avoiding or

Some individuals included in this study were already included in other publications from our group. Salivary concentrations of 3-nitrotyrosine[22], uric acid[23], malondialdehyde[24], and nitrites[25] were analyzed in those publications; but the objective of our current research was the determination of salivary TRX-1 levels.

THR-1 concentration in saliva was calculated using a solid-phase competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Whaltam, MA, United States), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, in each appropriate well: 100 μL standards or 100 μL saliva (diluted 4 times) were incubated overnight at 4-6 ºC (the plate was covered with a plate sealer for incubation). After washing each well with wash buffer, 100 μL biotinylated detection Ab working solution were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Again, after washing each well with wash buffer, 100 μL of streptavidin linked to Horseradish Peroxidase conjugate working solution was added into each well and incubated for 45 minutes at room temperature. After washing each well with wash buffer, 100 μL of Substrate Reagent (3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine as chromogenic substrate) were added to each well and incubated for 35 minutes at RT avoiding, at all times, direct light on the plate (reagent light-sensitive). Finally, 50 μL of stop solution (1 M H2SO4) was addeded to each well (yellow colour was developed) at room temperature. The calibrated curve was ranged between 0-25 ng/mL. Samples and standards absorbance units were read in a microplate spectrophotometer at 450 nm (Spectra MAX-190, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, United States). A four-parameter algorithm provides the best standard curve fit (the correlation coefficients of different kits ranged between 0.9971 and 0.9977). The limit of detection of the different assays was established in a range between 0.010 ng/mL and 0.017 ng/mL. Intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were calculated at < 10% and < 12%, respectively.

We reported categorical variables as number and percentage, and they were compared between groups by the χ2 test. We reported continuous variables as median and percentiles 25-75, and they were compared between groups by the Mann-Whitney U-test. We analysed the correlation between salivary TRX-1 concentrations and periodontitis severity by Spearman’s rho coefficient.

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was carried out to determine the variables that were associated with periodontitis. We included in the regression analysis those variables showing P value ≤ 0.05 when they were compared between subject groups and showing a reasonable number of events.

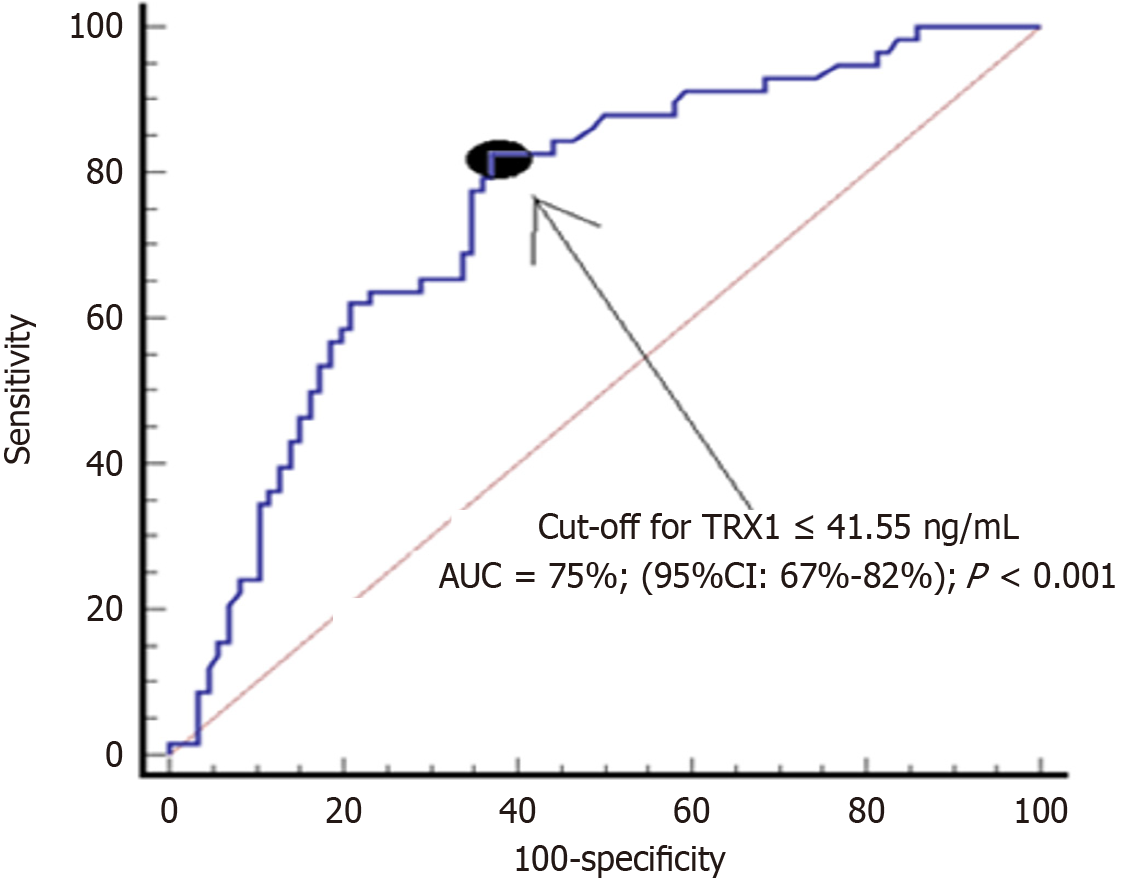

A receiver operating characteristic analysis was carried out to determine the ability of salivary TRX-1 concentrations to predict the diagnosis of periodontitis, and the area under curve (AUC) was reported. Negative and positive predictive values, sensitivity, negative and positive likelihood ratios and specificity for the cut-off (< 41.55 ng/mL) of salivary TRX-1 concentrations were reported. The value of cut-off was selected on the basis of the Youden J index[26].

MedCalc statistical software version 22.016 (MedCalc Software Ltd, Ostend, Belgium) and SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) were the programs used to carried out the statistical analyses.

A total of 144 subjects (58 with periodontitis and 86 without periodontitis) were included. We report the number of subjects in each periodontal stage and its salivary TRX-1 concentrations in Table 1, and we found significant differences in salivary TRX-1 concentrations according to periodontal stage (P < 0.001). Besides, we found a negative correlation between periodontitis severity and salivary TRX-1 concentrations (rho = -0.47; P < 0.001).

| Total (n = 144) | Salivary TRX-1 (ng/mL) median (P25%-75%) | P value | |

| < 0.001 | |||

| Periodontal health | 86 (59.7) | 55.6 (30.4-67.6) | |

| Periodontitis stage I | 16 (11.1) | 37.1 (27.8-54.8) | |

| Periodontitis stage II | 23 (16.0) | 29.7 (26.2-33.6) | |

| Periodontitis stage III | 13 (9.0) | 26.0 (22.6-31.2) | |

| Periodontitis stage IV | 6 (4.2) | 23.2 (18.4-26.5) |

Subjects with periodontitis, compared to subjects without periodontitis, had lower salivary TRX-1 concentrations (P < 0.001), higher rate of arterial hypertension (P < 0.001), a higher rate of cardiovascular disease (P = 0.03), a higher rate of diabetes mellitus (P = 0.03), lower rate of never smoker history (P < 0.001), a lower rate of tea consumption (P = 0.005), and were older (P < 0.001). No significant differences were found between both groups of subjects (without and with periodontitis) in immunosuppressive therapy, rheumatoid arthritis, radiotherapy, methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis, body mass index, hypercholesterolemia, obesity, coffee, alcohol and sex (Table 2). No subject (without or with periodontitis) had oral cancer, drug consumption or systemic lupus erythematosus.

| Subjects without periodontitis (n = 86) | Subjects with periodontitis (n = 58) | P value | |

| Gender female | 63 (73.3) | 36 (62.1) | 0.2 |

| Age (years) - median (P25%-75%) | 36 (20-44) | 59 (51-68) | < 0.001 |

| Arterial hypertension | 4 (4.7) | 17 (29.3) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 0 | 4 (6.9) | 0.03 |

| Hyperocholesterolemia | 2 (2.3) | 2 (3.4) | 0.99 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 | 4 (6.9) | 0.03 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 (2.3) | 3 (5.2) | 0.39 |

| Metrotexate for rheumatoid arthritis | 2 (2.3) | 0 | 0.52 |

| Immunosupressive therapy | 2 (2.3) | 1 (1.7) | 0.99 |

| Radiotherapy | 0 | 1 (1.7) | 0.4 |

| Body mass index (kg/m²) - median (P25%-75%) | 24.2 (22.4-26.6) | 24.8 (22.5-27.9) | 0.38 |

| Obesity | 11 (12.8) | 8 (13.8) | 0.99 |

| Never smoker | 66 (76.7) | 25 (43.1) | < 0.001 |

| Coffee | 68 (79.1) | 51 (87.9) | 0.19 |

| Tea | 20 (23.3) | 3 (5.2) | 0.005 |

| Alcohol | 33 (38.4) | 31 (53.4) | 0.09 |

| Salivary TRX-1 levels (ng/mL) - median (P25%-75%) | 55.6 (30.4-67.6) | 29.1 (25.0-34.5) | < 0.001 |

We found in multiple logistic regression analysis that age (years) (OR: 1.11; 95%CI: 1.064-1.165; P < 0.001) and salivary TRX-1 concentrations (ng/mL) (OR: 0.97; 95%CI: 0.946-0.998; P = 0.04) were the variables associated independently with periodontitis (Table 3).

| Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age (years) | 1.11 | 1.064-1.165 | < 0.001 |

| Salivary thioredoxin-1 levels (ng/mL) | 0.97 | 0.946-0.998 | 0.04 |

| Never smoker (yes vs non) | 0.54 | 0.195-1.469 | 0.23 |

| Arterial hypertension (yes vs non) | 1.17 | 0.263-5.223 | 0.84 |

| Tea consumption (yes vs non) | 0.30 | 0.044-2.027 | 0.22 |

We found an AUC of salivary TRX-1 for the diagnosis of periodontitis of 75% (95%CI: 67%-82%; P < 0.001) (Figure 1). The selected cut-off (< 41.55 ng/mL) of salivary TRX-1 concentrations to the diagnosis of periodontitis had a negative predictive value of 84% (75%-91%), a positive predictive value of 60% (53%-67%), a sensitivity of 83% (71%-91%), a negative likelihood ratio of 0.3 (0.2-0.5), a positive likelihood ratio of 2.2 (1.7-3.0), and a specificity of 63% (52%-73%).

Novel findings of this study were the association of low salivary TRX-1 concentrations with periodontitis and its severity, and the capacity of salivary TRX-1 concentrations to help in the periodontitis diagnosis.

TRX-1 in patients with periodontitis have been studied scarcely[17-19]. In a study by Foratori-Junior et al[17] with 18 periodontitis patients and 20 periodontally healthy subjects, a higher expression of TRX-1 in saliva was found in periodontitis patients than in healthy subjects. In a study by Hartenbach et al[18] with 30 periodontitis patients and 10 periodontally healthy subjects, a higher expression of TRX-1 in saliva was found in periodontitis patients than in healthy subjects. In a study by Toczewska et al[19] with 65 periodontitis patients and 31 periodontally healthy subjects a higher expression of TRX-1 gene in saliva was found in periodontitis patients than in healthy subjects, and a lower expression of TRX-1 gene in gingival tissue was found in periodontitis patients than in healthy subjects; however, the levels of TRX-1 in saliva and in gingival crevicular fluid were not determined.

Therefore, our study is the largest to date evaluating TRX-1 concentrations in patients with periodontitis (144 subjects). Our findings of lower salivary TRX-1 concentrations in subjects with, compared to without, periodontitis are contrary to those previous studies reporting that patients with periodontitis compared to periodontally healthy subjects showed a higher expression of TRX-1 or of TRX-1 gene in saliva[17-19]. However, our findings could be in consonance with those from one study with mice showing that mice with periodontitis compared to periodontally healthy mice showed a lower expression of TRX-1 in the periodontal tissues[16]. Curiously, in the study by Toczewska et al[19], it was found that the expression of TRX-1 gene in periodontitis patients, compared to healthy subjects, was lower in gingival tissue and higher in saliva. In addition, novel findings of our study were the association between low salivary TRX-1 concentrations and periodontitis independently of other factors according to the results of regression analysis.

Our observed findings about lower salivary TRX-1 concentrations in subjects with periodontitis and the association of low salivary TRX-1 concentrations with periodontitis could be explained by the fact that TRX-1 has effects on reducing oxidation and inflammation[12,13], and also on reducing tissue degradation in periodontitis[16]. Therefore the low salivary TRX-1 concentrations observed in patients with periodontitis in our series could be related to higher oxidation (due to higher ROS concentrations because TRX-1 does not neutralize ROS and does not activate other antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, GPX and CAT), higher inflammation (with higher production of pro-inflammatory citokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α), and greater tissue degradation (due to collagen degradation) in periodontitis.

We found that salivary TRX-1 concentrations have the capacity to help in the diagnosis of periodontitis. The area under curve that we found was not high (75%)[27]; therefore, salivary TRX-1 concentrations could help in the periodontitis diagnosis, but they could not be used alone as the sole diagnostic parameter. As the cut-off of salivary TRX-1 concentrations lower 41.55 ng/mL showed a sensitivity of 83%, there is a probability of 83% that a subject with TRX-1 lower 41.55 ng/mL has periodontitis. As the cut-off of salivary TRX-1 concentrations lower 41.55 ng/mL showed a specificity of 63%, there is a probability of 63% that a subject with TRX-1 higher 41.55 ng/mL does not have periodontitis. Further investigations are necessary to confirm those preliminary findings.

In some previous studies, a positive association between the expression of TRX-1 or of TRX-1 gene in saliva and periodontitis severity was found[18,19]. Thus, our findings of a negative association between salivary TRX-1 concentrations and periodontitis severity are contrary to those previous studies. Thus, the lower the salivary TRX-1 concentrations, the greater the periodontitis severity. The correlation that we found was not strong (rho = -0.47; P < 0.001)[28]; therefore, salivary TRX-1 concentrations could help predict the severity of periodontitis, but they could not be used alone as the sole predictive parameter. Further investigations are necessary to confirm those preliminary findings.

We found that higher age was another risk factor for periodontitis, as was previously described[29]. Other factors with a higher risk of periodontitis were previously documented, such as consumption of drugs, oral cancer, dental hygiene, alcohol, immunosuppression, coffee, tea and tobacco[30], obesity[31], systemic lupus erythematosus[32], sex[33], rheu

A point of interest is that thioredoxin system activity could be modulated by different antagonist and agonist agents of each member of the thioredoxin system[6-11]. On the one hand, the administration of TRX-1 agonists, TrxR agonists and TXNIP antagonists may be beneficials in age-associated diseases and in preventing cancer (reducing mutation accumulation) due to its anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects. On the other hand, the administration of TRX-1 antagonists, TrxR antagonists and TXNIP agonists might help in anticancer treatments to hinder tumor pro

With respect to periodontitis, in a study performed by Wu et al[16] including mice with diabetes mellitus and periodontitis, an increased ROS production and reduced TRX-1 expression were found in the periodontal tissues of mice with periodontitis compared to mice with periodontal health. In addition, it was found that the administration of recombinant human TRX-1 restored this reduced TRX-1 expression, decreased ROS generation and promoted the alveolar bone repair in periodontitis.

We recognize that our study has some limitations. One issue was that TRX-1 concentrations in other samples (gingival crevicular fluid, gingival tissue, or blood) was not determined, although we designed this study with the aim of being as non-invasive as possible. In addition, it is possible that more factors associated with periodontitis could have been found by including more subjects in the study. Besides, the observational nature of the study could imply the presence of some potential bias and that some unmeasured variables could influence the observed findings. In addition, sample size was not calculated; however, it was sufficient to find an association between low salivary TRX-1 levels and periodontitis. Therefore, further investigations are necessary to confirm these preliminary findings.

On the contrary, we think that our study also showed some strengths. This study has a larger sample and used a minimally invasive biologic sample (saliva) compared to previously published studies on TRX-1 in periodontitis, and it is the first one reporting the association of periodontitis and its severity with low salivary TRX-1 levels.

Finally, with respect to future research directions, it could be interesting to determine the role of salivary TRX-1 concentrations in the development of periodontitis, periodontitis severity and periodontitis diagnosis in periodontitis in larger studies controlling for more variables, and to determine the effects of the administration of agents that modulate thioredoxin system activity in randomized clinical trials on the clinical evolution of periodontitis and on the concentrations of oxidative and inflammatory buccal biomarkers. The diagnosis and follow-up of periodontitis have tra

Novel findings of this study were the association of low salivary TRX-1 concentrations with periodontitis and its severity, and the capacity of salivary TRX-1 concentrations to help in the periodontitis diagnosis. Further investigations are necessary to confirm those preliminary findings.

Centro Integrado de Formacion Profesional (CIFP) Los Gladiolos (Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain) has facilitated the in

| 1. | Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 2005;366:1809-1820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2486] [Cited by in RCA: 2791] [Article Influence: 132.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | GBD 2021 Oral Disorders Collaborators. Trends in the global, regional, and national burden of oral conditions from 1990 to 2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2025;405:897-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 134.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sharma S, Kishen A. Applications of immunomodulatory nanoparticles in dentistry. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2026;21:101-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Toczewska J, Konopka T. Activity of enzymatic antioxidants in periodontitis: A systematic overview of the literature. Dent Med Probl. 2019;56:419-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Xin Y, Wang Y. Programmed Cell Death Tunes Periodontitis. Oral Dis. 2025;31:1583-1594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yang B, Lin Y, Huang Y, Shen YQ, Chen Q. Thioredoxin (Trx): A redox target and modulator of cellular senescence and aging-related diseases. Redox Biol. 2024;70:103032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cao X, He W, Pang Y, Cao Y, Qin A. Redox-dependent and independent effects of thioredoxin interacting protein. Biol Chem. 2020;401:1215-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dagdeviren S, Lee RT, Wu N. Physiological and Pathophysiological Roles of Thioredoxin Interacting Protein: A Perspective on Redox Inflammation and Metabolism. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2023;38:442-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Qayyum N, Haseeb M, Kim MS, Choi S. Role of Thioredoxin-Interacting Protein in Diseases and Its Therapeutic Outlook. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:2754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Choi EH, Park SJ. TXNIP: A key protein in the cellular stress response pathway and a potential therapeutic target. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55:1348-1356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 67.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Seitz R, Tümen D, Kunst C, Heumann P, Schmid S, Kandulski A, Müller M, Gülow K. Exploring the Thioredoxin System as a Therapeutic Target in Cancer: Mechanisms and Implications. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024;13:1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yang S, Yang X. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Periodontitis: A Potential Therapeutic Target. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2025;13:e70301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Viglianisi G, Tartaglia GM, Santonocito S, Amato M, Polizzi A, Mascitti M, Isola G. The Emerging Role of Salivary Oxidative Stress Biomarkers as Prognostic Markers of Periodontitis: New Insights for a Personalized Approach in Dentistry. J Pers Med. 2023;13:166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lee CY, Choy CS, Lai YC, Chang CC, Teng NC, Huang WT, Lin CT, Huang YK. A Cross-Sectional Study of Endogenous Antioxidants and Patterns of Dental Visits of Periodontitis Patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chang CH, Han ML, Teng NC, Lee CY, Huang WT, Lin CT, Huang YK. Cigarette Smoking Aggravates the Activity of Periodontal Disease by Disrupting Redox Homeostasis- An Observational Study. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wu J, Huang Y, Zhan C, Chen L, Lin Z, Song Z. Thioredoxin-1 promotes the restoration of alveolar bone in periodontitis with diabetes. iScience. 2023;26:107618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Foratori-Junior GA, Ventura TMO, Grizzo LT, Carpenter GH, Buzalaf MAR, Sales-Peres SHC. Label-Free Quantitative Proteomic Analysis Reveals Inflammatory Pattern Associated with Obesity and Periodontitis in Pregnant Women. Metabolites. 2022;12:1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hartenbach FARR, Velasquez É, Nogueira FCS, Domont GB, Ferreira E, Colombo APV. Proteomic analysis of whole saliva in chronic periodontitis. J Proteomics. 2020;213:103602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Toczewska J, Baczyńska D, Zalewska A, Maciejczyk M, Konopka T. The mRNA expression of genes encoding selected antioxidant enzymes and thioredoxin, and the concentrations of their protein products in gingival crevicular fluid and saliva during periodontitis. Dent Med Probl. 2023;60:255-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tonetti MS, Greenwell H, Kornman KS. Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45 Suppl 20:S149-S161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 796] [Cited by in RCA: 747] [Article Influence: 93.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Navazesh M. Methods for collecting saliva. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;694:72-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 769] [Cited by in RCA: 921] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lorente L, Hernández Marrero E, Abreu González P, Lorente Martín AD, González-Rivero AF, Marrero González MJ, Hernández Marrero C, Hernández Marrero O, Jiménez A, Hernández Padilla CM. High Salivary 3-Nitrotyrosine Levels in Periodontitis. J Clin Med. 2025;14:6785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lorente L, Hernández Marrero E, Abreu-Gonzalez P, Lorente Martín AD, González-Rivero AF, Marrero González MJ, Hernández Marrero C, Hernández Marrero O, Jiménez A, Hernández Padilla CM. Low salivary uric acid levels are independently associated with periodontitis. World J Clin Cases. 2025;13:105911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 24. | Lorente L, Hernández Marrero E, Abreu González P, Lorente Martín AD, González-Rivero AF, Marrero González MJ, Hernández Marrero C, Hernández Marrero O, Jiménez A, Hernández Padilla CM. High Salivary Malondialdehyde Levels Are Associated with Periodontitis Independently of Other Risk Factors. J Clin Med. 2025;14:2993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lorente L, Hernández Marrero E, Abreu González P, Lorente Martín AD, González-Rivero AF, Marrero González MJ, Hernández Marrero C, Hernández Marrero O, Jiménez A, Hernández Padilla CM. Observational prospective study to determine the association and diagnostic utility of salivary nitrite levels in periodontitis. Quintessence Int. 2025;56:100-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | YOUDEN WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3:32-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Çorbacıoğlu ŞK, Aksel G. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in diagnostic accuracy studies: A guide to interpreting the area under the curve value. Turk J Emerg Med. 2023;23:195-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Akoglu H. User's guide to correlation coefficients. Turk J Emerg Med. 2018;18:91-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1388] [Cited by in RCA: 2797] [Article Influence: 349.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Billings M, Holtfreter B, Papapanou PN, Mitnik GL, Kocher T, Dye BA. Age-dependent distribution of periodontitis in two countries: Findings from NHANES 2009 to 2014 and SHIP-TREND 2008 to 2012. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45 Suppl 20:S130-S148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Salvi GE, Roccuzzo A, Imber JC, Stähli A, Klinge B, Lang NP. Clinical periodontal diagnosis. Periodontol 2000. 2023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Adam M. Obesity as a risk factor for periodontitis - does it really matter? Evid Based Dent. 2023;24:48-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Tan PR, Lee AJL, Zhao JJ, Chan YH, Fu JH, Ma M, Tay SH. Higher odds of periodontitis in systemic lupus erythematosus compared to controls and rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review, meta-analysis and network meta-analysis. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1356714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Shiau HJ, Reynolds MA. Sex differences in destructive periodontal disease: a systematic review. J Periodontol. 2010;81:1379-1389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rodríguez-Lozano B, González-Febles J, Garnier-Rodríguez JL, Dadlani S, Bustabad-Reyes S, Sanz M, Sánchez-Alonso F, Sánchez-Piedra C, González-Dávila E, Díaz-González F. Association between severity of periodontitis and clinical activity in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a case-control study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Enteghad S, Shirban F, Nikbakht MH, Bagherniya M, Sahebkar A. Relationship Between Diabetes Mellitus and Periodontal/Peri-Implant Disease: A Contemporaneous Review. Int Dent J. 2024;74:426-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Tada A, Tano R, Miura H. The relationship between tooth loss and hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2022;12:13311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Radu CM, Radu CC, Zaha DC. Salivary and Microbiome Biomarkers in Periodontitis: Advances in Diagnosis and Therapy-A Narrative Review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2025;61:1818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Alavi SE, Sharma LA, Sharma A, Ebrahimi Shahmabadi H. Salivary Biomarkers in Periodontal Disease: Revolutionizing Early Detection and Precision Dentistry. Mol Diagn Ther. 2025;29:721-740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sunila BS, Shivakumar GC, Abdul NS, Sudhakar N, Franco R, Ronsivalle V, Cicciù M, Minervini G. Conventional periodontal probing versus salivary biomarkers in diagnosis and evaluation of chronic periodontitis in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Minerva Dent Oral Sci. 2025;74:187-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Chukwuma D, Arowojolu M, Ankita J. A Review Of Salivary Biomarkers Of Periodontal Disease. Ann Ib Postgrad Med. 2024;22:106-115. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Benni D, K M P, Maddukuri T, Singh R, Gahlot JK, Basu P, Kumari A. Salivary diagnostics: Bridging dentistry and medicine: A systematic review. Bioinformation. 2024;20:1754-1759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Sánchez-Medrano AG, Martinez-Martinez RE, Soria-Guerra R, Portales-Perez D, Bach H, Martinez-Gutierrez F. A systematic review of the protein composition of whole saliva in subjects with healthy periodontium compared with chronic periodontitis. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0286079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/