Published online Feb 6, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i4.117692

Revised: January 1, 2026

Accepted: January 16, 2026

Published online: February 6, 2026

Processing time: 54 Days and 9.2 Hours

Autoimmune and rare ophthalmic diseases can affect not only vision but also patients’ mental well-being and everyday functioning; however, psychological aspects remain under-assessed in routine eye care.

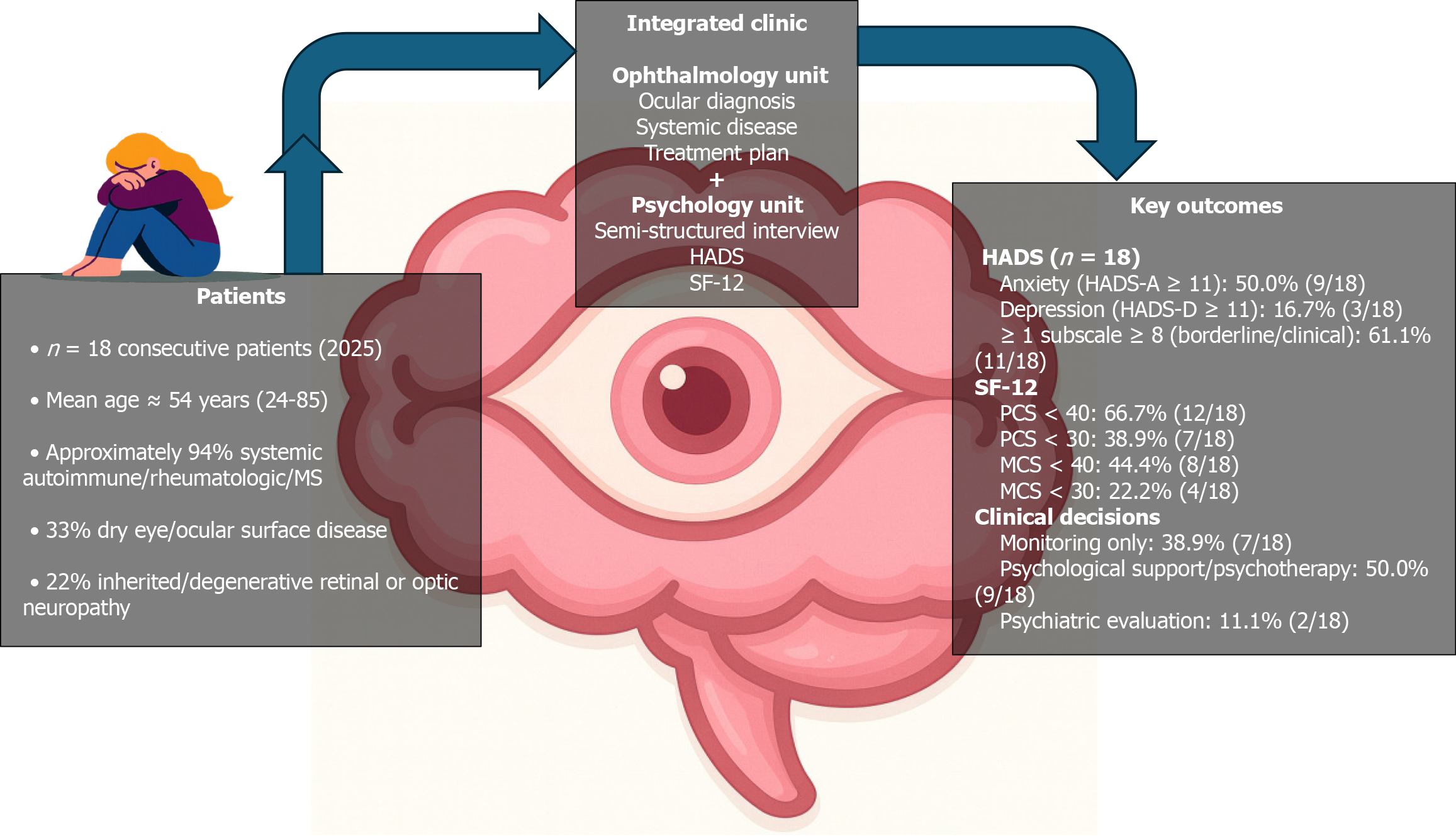

To investigate a descriptive consecutive case series reporting 18 adults evaluated at a newly established integrated psycho-ophthalmology clinic in Catania, Italy, where ophthalmologists and psychologists jointly assessed patients with complex inflammatory, autoimmune, or degenerative ocular conditions.

All participants completed a semi-structured clinical psychological interview and brief standardized screening for anxiety/depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life [Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12)].

The cohort had a mean age of 54.2 ± 15.6 years (range 24-85), and most patients (17/18) had systemic autoimmune, rheumatologic, or demyelinating comorbidity; dry eye/ocular surface disease was present in 6/18 (33.3%). Clinically significant anxiety symptoms (HADS-anxiety ≥ 11) were observed in 9/18 patients (50.0%), while clinically significant depressive symptoms [HADS-depression (HADS-D) ≥ 11] were present in 3/18 (16.7%), with an additional 6/18 (33.3%) showing borderline depressive scores (HADS-D 8-10). Physical health-related quality of life was markedly reduced (mean SF-12 physical 35.8 ± 10.9), with 12/18 (66.7%) scoring < 40; mental quality of life was more heterogeneous (mean SF-12 mental 41.3 ± 12.3), with 8/18 (44.4%) scoring < 40. Findings were clinically actionable: Based on the integrated assessment (scores plus interview), structured psychological support or psychotherapy was recommended for 9/18 (50.0%) patients, and a more in-depth psychiatric/psychological evaluation for 2/18 (11.1%).

This pilot series highlights the high psychological burden and functional impairment in autoimmune and rare ophthalmic populations and supports the feasibility and clinical utility of embedding brief mental health screening plus focused interview within routine ophthalmic care.

Core Tip: Patients living with rare and autoimmune eye diseases frequently face chronic pain, fear of blindness, diagnostic uncertainty, and disruption of social and work roles. In this pilot psycho-ophthalmology case series from an integrated ophthalmology-psychology clinic, about half of the patients showed clinically relevant anxiety, and many reported markedly impaired physical and, to a lesser extent, mental quality of life, despite the small sample size. Systematic use of brief standardized instruments (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and 12-item Short Form Health Survey), combined with a focused clinical interview, proved feasible in routine care and directly informed decisions about psychological or psychiatric referral. Embedding mental health assessment within ophthalmology services may help clinicians identify vulnerable patients earlier, address emotional distress and maladaptive coping, and ultimately support better adaptation to chronic visual disease and complex immunomodulatory treatments.

- Citation: Capobianco M, Zeppieri M, Nicolosi SG, Faro GD, Salanitro D, Khouyyi M, D’Esposito F, Gagliano C. When eye disease affects the mind: Psychological burden and functioning in autoimmune ophthalmology. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(4): 117692

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i4/117692.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i4.117692

Visual impairment and chronic eye disease are increasingly recognized as major determinants of both functional disability and mental health. Recent global estimates suggest that more than 2.2 billion people live with some form of visual impairment, and this number is expected to rise as populations age and age-related eye diseases become more prevalent[1]. In both population-based and clinic-based meta-analyses, depression is consistently more frequent among people with visual impairment than among those with normal vision. In eye-care and low-vision settings, approximately one quarter of older adults with visual impairment meet criteria for depression. This prevalence is about twice that reported among community-dwelling older adults without visual loss[2,3]. Anxiety is similarly common. A recent meta-analysis of 95 studies reported pooled prevalence estimates of 31% for anxiety symptoms and 19% for anxiety disorders in ophthalmic populations, with roughly a twofold increased risk compared with healthy controls[4].

Beyond these aggregate figures, ophthalmic disorders have become a central focus for emerging “psycho-ophthalmology” and consultation-liaison psychiatry, which explicitly study the bidirectional links between eye disease and mental health[5-8]. Narrative and systematic reviews report high rates of depressive and anxiety symptoms across a wide spectrum of ophthalmic diagnoses, together with stress-related and grief-like reactions to vision loss, and document substantial impacts on quality of life, social functioning, and, in some settings, adherence to long-term glaucoma treatment[5-8]. Eye disease challenges a core “vision-identity-autonomy” axis: How patients see the world, how they see themselves, and how independently they can act within it, as reflected in reports of increased dependence, social isolation, and complex emotional responses among people living with glaucoma, dry eye disease (DED), and visual impairment[5-8]. In chronic and progressive, or immune-mediated, ophthalmic conditions, recurrent disease activity, visible ocular changes, burdensome treatment regimens, and prognostic uncertainty can further erode patients’ sense of bodily control, social roles, and plans, reinforcing the need for integrated psycho-ophthalmic care[6-8].

Autoimmune and inflammatory eye diseases illustrate this burden particularly clearly. Patients with non-infectious uveitis or scleritis experience recurrent flares, ocular pain, photophobia, and the constant threat of irreversible visual loss. Meta-analytic and cross-sectional data suggest that around 39% of patients with uveitis experience clinically relevant anxiety and about 15%-20% meet criteria for depression, while in non-infectious scleritis cohorts roughly one in five patients carries a formal mental health diagnosis, most commonly major depression or generalized anxiety disorder; pooled across ocular inflammatory diseases, average prevalences of depression and anxiety of approximately 31% and 35% have been reported, with higher symptom scores in those with more severe or painful disease[9-13]. Across inflammatory eye diseases, including chronic ocular surface disease, uveitis, and scleritis, co-existing anxiety and depression are consistently linked to heavier treatment burden, worse patient-reported symptom scores, and marked reductions in health-related quality of life, limiting work participation, mobility, and social functioning even when visual acuity re

Ocular surface disease, particularly DED, adds another layer of complexity and is highly relevant in autoimmune settings such as Sjögren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic sclerosis. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses report that depression and anxiety are very common in DED: Basilious et al[9] found a prevalence of depressive sy

Rare hereditary and other low-prevalence retinal diseases provide a parallel illustration of how ophthalmic disorders can reshape patients’ emotional lives. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures in retinal disease shows that these conditions substantially affect quality of life. At the same time, existing instruments often provide only partial coverage of the relevant domains[15]. In a large qualitative study including 32 participants with hereditary retinal diseases and 47 with acquired retinal diseases, nine quality-of-life domains were identified: Activity limitation (for example, difficulties with reading, driving, shopping, and using computers), emotional well-being, social relationships, symptoms, health concerns, mobility and orientation, practical inconveniences, economic impact, and coping[16]. Participants with hereditary retinal diseases, typically younger, working-age adults with long-standing bilateral and progressive visual impairment, reported more issues across most domains than those with acquired retinal diseases, including marked restrictions in mobility, employment and finances, social interaction and participation, along with fears of accidents, going blind, future disease progression, and passing the condition on to their children[16]. Emotional narratives frequently featured frustration, anxiety, shock at being told they were or would become legally blind, uncertainty about the future, and feelings of isolation, as well as disruption of work and family roles[16]. When these disease-specific findings are considered alongside evidence that autoimmune diseases overall are associated with an approximately 1.8-fold increased risk of depression, and that depression similarly increases the subsequent risk of autoimmune disease[17], with consistent data linking autoimmune and inflammatory eye diseases to elevated rates of anxiety, depression, and reduced quality of life[1,5,9,12]. Autoimmune and rare eye diseases together offer a useful model for understanding how chronic disruption of visual function translates into sustained psychological burden and fun

Several autoimmune eye conditions occur in the context of systemic autoimmune or connective-tissue disease. A recent large-scale systematic review and meta-analysis including over 39 million participants confirmed a bidirectional association between autoimmune diseases and depression: Patients with autoimmune disorders had an approximately 80% higher risk of developing depression, and individuals with depression also showed increased incidence of auto

In rheumatoid arthritis, higher HADS scores are associated with greater pain, fatigue, functional disability, and higher composite disease activity scores-largely through their impact on tender joint counts and patient global assessment-as well as poorer health-related quality of life; depressive symptoms have also been linked to increased health-care utilization and reduced treatment adherence[18-20]. In systemic sclerosis and primary Sjögren’s syndrome, HADS-defined anxiety and depression show similarly high prevalence and correlate with global disability, organ-specific limitations (hand and mouth function, ocular and oral involvement), fatigue, and work impairment, together with worse patient-reported quality-of-life indices[21,22]. Taken together, these findings highlight a tight interplay between systemic inflammation, symptom burden, and psychological distress across autoimmune rheumatic diseases[17-22].

To capture this multidimensional impact in routine care, brief self-report instruments that quantify both psychological symptoms and health-related functioning are required. The HADS is widely used in patients with chronic medical conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, and primary Sjögren’s syndrome, as a screening tool for anxiety and depressive symptoms[4,18-22]. In these populations it shows good internal consistency and robust Rasch model fit[18], correlates closely with established mental health measures and with indices of disability, fatigue and disease impact such as health assessment questionnaire, EuroQol-5 dimension and mouth/hand disability scores[18,20,21], and its anxiety and depression scores are independently associated with tender joint counts, patient global ass

Importantly, HADS was designed to minimize somatic items that may overlap with physical illness, making it particularly suitable for patients with significant systemic and ocular comorbidity[4,18-22].

The 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) is a generic measure of health-related quality of life that yields separate physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores. In rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, SF-12 PCS and MCS scores demonstrate high completion rates, acceptable reliability, a clear two-factor physical/mental structure, and very strong correlations with the corresponding SF-36 component scores and with functional measures such as the health assessment questionnaire and disease-specific hand outcomes[23-25]. Lower PCS and MCS values consistently discriminate between levels of pain severity and functional class, and track changes in symptom burden over time, indicating that they capture both physical limitations and mental health burden in inflammatory arthritis[23-25]. On this basis, the combined use of HADS and SF-12 offers a pragmatic, time-efficient approach to characterizing psychological distress and overall health-related quality of life in patients with complex autoimmune and rare ophthalmic conditions in everyday clinical practice.

In parallel, the emerging field of psycho-ophthalmology and several liaison models have argued for closer integration between ophthalmology and mental health services[5-8]. Conceptual papers and narrative reviews describe how such integration could be organized, but empirical evaluations of fully integrated ophthalmology-psychology/psychiatry pathways remain limited. Only a small number of reports provide any detail on clinic configuration, referral criteria, the use of standardized assessment instruments, and how psychological findings inform specific interventions such as counselling, structured psychotherapy, or psychiatric consultation[5-8]. Moreover, these publications rarely focus on autoimmune or rare eye diseases, which are typically managed in tertiary or multidisciplinary clinics and often involve complex immunomodulatory regimens and prolonged diagnostic work-up, leaving an evidence gap for this subgroup of patients.

Against this background, there is a need for pragmatic, clinically grounded descriptions of how integrated psycho-ophthalmology services can be organized and what types of patients they see. The present pilot case series arises from a newly established psycho-ophthalmology clinic in Catania, Italy, where ophthalmologists and psychologists jointly assessed patients with complex inflammatory, autoimmune, or degenerative ocular conditions. Using a structured clinical psychiatric interview in combination with the HADS and SF-12 as brief measures of anxiety, depression and health-related quality of life, we aimed to (1) Characterize the burden of anxiety, depressive symptoms and physical and mental quality-of-life impairment in patients referred to this integrated service; and (2) Document how these assessments informed concrete clinical outputs, including psychological follow-up, psychotherapy and psychiatric referral. By focusing on a mixed cohort of patients with autoimmune and rare ophthalmic diseases, this study seeks to highlight the often-overlooked psychosocial burden of these conditions and to illustrate a feasible model for embedding mental health assessment within routine ophthalmic care.

This study is a descriptive, consecutive case series conducted at the Ophthalmology Unit of PO San Marco Hospital, Catania (Italy), in collaboration with the hospital Psychology Unit. The psycho-ophthalmology pathway was established under a formal memorandum of understanding between the two units, with the aim of providing integrated assessment and support for patients with complex ocular and systemic disease. All evaluations included in this report were performed in routine clinical practice during 2025, within this integrated ophthalmology-psychology framework.

Participants were adults (≥ 18 years) with rare and/or severe ophthalmic disease, often in the context of systemic autoimmune or connective-tissue disorders, who ophthalmologists referred for a psychological evaluation in 2025. All subsequent assessments were performed as part of standard clinical practice from January to October 2025, with an

Referral was considered for patients who, in the judgment of the treating ophthalmologist, presented with at least one of the following: Rare, degenerative, or potentially sight-threatening ocular disease (e.g., retinitis pigmentosa, Leber hereditary optic neuropathy, cicatricial pemphigoid, neuropathic optic damage). Systemic autoimmune disease with actual or suspected ocular involvement (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, psoriatic arthritis, mixed or undifferentiated connective-tissue disease, multiple sclerosis, Sjögren’s syndrome, lupus/connective-tissue disease). Clinically relevant distress related to diagnosis, pain, treatment burden, or fear of visual loss emerging during ophthalmologic consultations.

For the present analysis, we included all consecutively referred patients who completed the joint assessment (clinical interview plus questionnaires) and for whom anonymized clinical data were available, yielding a total sample of 18 patients. No additional exclusion criteria were applied beyond the need to be able to participate in an interview and complete self-report measures.

HADS: Symptoms of anxiety and depression were assessed using the HADS, a 14-item self-report instrument developed for use in medical settings to detect anxiety and depressive states while minimizing confounding by somatic symptoms (e.g., fatigue, insomnia) related to physical illness[26]. The scale comprises two 7-item subscales: HADS-anxiety (HADS-A) and HADS-depression (HADS-D). Each item is scored from 0 to 3, giving subscale scores ranging from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. Consistent with commonly used conventions in chronic disease populations, scores of 0-7 were treated as non-cases, 8-10 as “borderline” or “at risk”, and ≥ 11 as indicative of clinically significant anxiety or depressive symptoms. These cut-offs were used descriptively, in combination with clinical judgement, rather than as rigid diagnostic thresholds.

SF-12: Health-related quality of life was assessed using the SF-12. This generic, widely used instrument reproduces the PCS and MCS scores of the longer SF-36[27]. The SF-12 yields two summary indices-PCS-12 and MCS-12-that are usually scored using norm-based algorithms, with a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10 in the general population. In line with this approach, lower PCS scores were interpreted as indicating worse physical functioning and greater somatic burden. In contrast, lower MCS scores were associated with poorer mental well-being and psychological functioning. For clinical interpretation in this small case series, values below approximately 40 were considered to reflect at least moderate impairment, and values below approximately 30 to indicate marked impairment in the corresponding domain, taking into account age, comorbidities, and the clinical interview.

In addition to self-report measures, all patients underwent a semi-structured clinical psychological interview conducted by a psychologist with experience in health and liaison psychology. The interview systematically explored Patients’ narratives of the ocular and systemic diagnoses (timing, diagnostic odyssey, perceived clarity of information). Emotional reactions to diagnosis and disease course (shock, fear, anger, sadness, relief). Pain and other distressing physical symptoms, with particular attention to chronic ocular discomfort (e.g., dry eye, photophobia, burning, fluctuating vision) and systemic pain. Perceived impact on family life, intimate relationships, and caregiving roles. Work and role fun

To diminish subjectivity and standardize reporting, interview results have been encapsulated utilizing a systematic coding framework. Subsequent to each consultation, the psychologist has filled out a concise, structured template addressing specified domains (diagnostic experience, predominant emotional response, pain/symptom distress, functional impact, coping style, previous mental health history, and protective variables). A principal ‘predominant psychological pattern’ designation has been allocated utilizing operational descriptors (e.g., predominant anxiety/health concerns; adjustment challenges due to fear of visual impairment; depressive characteristics/low mood; burnout/work-related distress; mixed anxiety-depressive features). The ‘Brief psychological profile’ section in Table 1 presents this coded synthesis in succinct, clinically focused terminology rather than a literal narrative. In the presence of doubt, the summary label has been revised following a collaborative assessment by the integrated team to guarantee alignment with questionnaire scores and functional impact. At the end of each assessment, the psychologist formulated a brief narrative synthesis of the patient’s psychological profile (e.g., predominant anxiety, depressive features, adjustment difficulties, personality style) and an overall clinical judgement regarding the need for psychological or psychiatric follow-up.

| ID | Age | Main systemic pathologies | Eye pathology | Dry eye | Brief psychological profile | HADS A/D | SF-12 PCS/MCS | Psychological judgment |

| P01 | 41 | Scleroderma; endometriosis | - | No | High anxiety, depressed mood, severe work-related stress; clinically relevant symptoms | 16/15 | 25/24 | Recommended psychological path |

| P02 | 47 | Granulomatosis | - | No | Initial low mood, anger/sadness, then improved coping; non-clinical anxiety/depression | 5/2 | 37/49 | No urgent indications |

| P03 | 52 | Sjögren’s syndrome | Ocular involvement compatible with DED | Yes | Previous anxiety/depression (episodes in youth); currently compensated; aesthetic factors (alopecia) as triggers | 6/7 | 52.4/60.6 | No urgency, possible support |

| P04 | 50 | Scleroderma | - | No | Mild anxiety; experience of “invisible” illness; impact on work | 5/2 | 35/53 | Monitoring, not urgent |

| P05 | 79 | Familiarity with retinitis pigmentosa | Retinitis pigmentosa | No | Mood swings, anxious-depressive episodes in the past; currently compensated | 6/6 | 49/58 | No current indications |

| P06 | 24 | Psoriatic arthritis | - | No | Difficulty in talking about oneself; marked subjective suffering; anxiety/depression in the risk range | 12/10 | 26/40 | Psychological counseling (individual or group) recommended |

| P07 | 64 | Rheumatoid arthritis; Sjögren’s syndrome; dry eye story | Dry eye | Yes | Mood swings; recalls past events with emotional charge; anxiety/depression at risk | 6/7 | 42/50 | Monitoring, possible support |

| P08 | 55 | Undifferentiated progressive connective tissue disease; dry eye | Dry eye | Yes | Recent episode of job burnout; emotional instability; mild anxiety, at-risk depression | 4/10 | 34/31 | Psychological support recommended |

| P09 | 26 | Multiple sclerosis; psoriatic arthritis | - | No | Moderate anxiety; mild depression; impact of pregnancy and physical conditions | 4/2 | 24/58 | Monitoring, possible support |

| P10 | 51 | Psoriatic arthritis | Optic neuropathy | No | Mild anxiety/depression; severe work stress (nurse); family conflicts | 5/3 | 19/51 | Possible support, not urgent |

| P11 | 67 | Rheumatoid arthritis for 12 years; Raynaud’s phenomenon | Dry eye | Yes | Very severe chronic pain; perception of poor treatment effectiveness; significant anxiety and depression | 13/7 | 38/28 | Recommended supportive psychotherapy path |

| P12 | 85 | Multiple sclerosis; rheumatoid arthritis; Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy | Leber’s neuropathy | No | Mood swings, tearfulness, feelings of guilt/inadequacy; significant anxiety/depression | 11/12 | 52/27 | A thorough psychological evaluation is recommended |

| P13 | 56 | Suspected rare disease (under definition) | Recurrent dry eye | Yes | Controlling personality structure; anxiety at risk; no depression; progressive emotional openness | 8/1 | 44/46 | Suggested support for managing anxiety and diagnostic uncertainty |

| P14 | 58 | Cicatricial pemphigoid | Corneal complications (perforation) | Yes | Marked anxiety, fear of complications; depression in the risk range | 14/9 | 36/32 | Psychological/psychotherapeutic evaluation recommended |

| P15 | 48 | Rheumatoid arthritis (recent); mother with the same pathology | - | No | Severely emotionally affected; full-blown anxiety, at risk of depression | 12/9 | 26/32 | Recommended start of psychological path |

| P16 | 47 | Suspected mixed connective tissue disease | - | No | Chronic suffering, daily fatigue, clinical anxiety, mild depression | 14/9 | 29/45 | Psychological support recommended |

| P17 | 56 | Suspected rheumatoid arthritis; previous leukemia | - | No | Marked mood swings, feelings of discouragement and “depression”; high anxiety/depression; possible eating disorder | 15/12 | 24/29 | Psychiatric/psychological further investigation indicated |

| P18 | 69 | Lupus/connective tissue disease; myopic retinopathy | Myopic retinopathy | No | Initial crisis at diagnosis; current good acceptance; moderate anxiety, mild depression | 11/8 | 52/30 | Psychological evaluation recommended (not urgent) |

Patients were first evaluated in the Ophthalmology Unit as part of routine care. When the ophthalmologist identified the need for a psychological assessment, based on disease complexity, long-standing autoimmune or rare conditions, expressed distress, or difficulties in adapting to treatment, patients were offered a joint psycho-ophthalmology appointment. This took place in the same hospital, in a setting shared by the Ophthalmology and Psychology Units in accordance with the memorandum of understanding between the two services.

During the integrated visit: (1) Ophthalmologic review summarized the current ocular condition, systemic diagnosis, ongoing immunomodulatory or other treatments, and the patient’s recent clinical course; (2) Psychological assessment was then conducted in a dedicated consultation, usually on the same day. The psychologist administered the HADS and SF-12 in paper-and-pencil format (or read the items aloud as needed) and conducted the semi-structured clinical interview described above; and (3) At the end of the encounter, joint feedback was provided to the patient by the ophthalmologist and psychologist, discussing the main findings and possible implications for both ophthalmologic and psychological care.

For this case series, “clinically significant symptoms” were considered present when at least one of the following applied: HADS-A or HADS-D score ≥ 11. Borderline HADS scores (8-10) combined with clear evidence of emotional distress, functional impairment, or maladaptive coping in the clinical interview. Severely reduced MCS scores (approximately < 30), indicating marked impairment in mental quality of life.

Recommendations for psychological or psychiatric care were made on the basis of the integrated clinical picture: No urgent intervention/monitoring: Minimal or subclinical symptoms, adequate coping and support, no major functional impairment. Psychological support or psychotherapy: Persistent anxiety, depressive symptoms, or adjustment diffi

These decisions were recorded in the clinical chart as part of routine practice and are summarized in the descriptive table of the 18 cases (e.g., recommendations for psychological follow-up, suggestions for supportive psychotherapy, indications for psychiatric consultation).

Given the small sample size and the exploratory nature of this pilot series, analyses were purely descriptive. Continuous variables such as age, HADS-A, HADS-D, SF-12 PCS, and SF-12 MCS were summarized using means, standard de

For descriptive purposes, HADS-A and HADS-D scores were also categorized into non-case (0-7), borderline (8-10) and clinically significant (≥ 11) bands, and SF-12 PCS and MCS scores were grouped into approximate ranges (≥ 50, 40-49, < 40, < 30) to illustrate gradients of physical and mental health-related quality of life. No formal hypothesis testing or multivariable modelling was attempted, as the aim was to provide a detailed clinical description rather than to test specific statistical hypotheses. All analyses were performed using standard statistical software.

The psycho-ophthalmology pathway was implemented as part of routine integrated care at PO San Marco Hospital, in accordance with institutional policies and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The present report is based on anonymized data extracted from clinical records of patients seen in 2025.

A total of 18 consecutive adult patients were assessed in the integrated psycho-ophthalmology clinic in 2025. The mean age was 54.2 ± 15.6 years (median 53.5; range 24-85 years). Almost all patients (17/18) had at least one systemic autoimmune, rheumatologic, or demyelinating disease, including rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis, systemic sclerosis, undifferentiated or mixed connective-tissue disease, Sjögren’s syndrome, multiple sclerosis, lupus/connective-tissue disease, cicatricial pemphigoid, granulomatosis, and suspected rare systemic disorders. One patient presented with inherited retinal degeneration in the context of a strong family history of retinitis pigmentosa.

Ocular diagnoses included dry eye or recurrent ocular surface disease in 6 patients (33.3%; including Sjögren-related ocular involvement, dry eye associated with connective-tissue disease and cicatricial pemphigoid with corneal complications), inherited or degenerative retinal/optic neuropathies in 4 patients (22.2%; retinitis pigmentosa, Leber hereditary optic neuropathy, myopic retinopathy and previous optic neuropathy), and systemic autoimmune disease with limited or no overt structural ocular damage at the time of assessment in the remaining cases.

Dry eye (definite or highly probable) was present in 6 of 18 patients (33.3%), all of whom had an underlying auto

From a qualitative perspective, the psychological summaries described chronic pain and a perception of limited treatment efficacy in some patients, marked work-related stress or recent burnout in others, and frequent references to fear of complications, diagnostic uncertainty, and concerns about long-term disability or blindness.

Group-level HADS scores were in the mild-to-moderate range on average. Mean HADS-A was 9.3 ± 4.2 (median 9.5; range 4-16), and mean HADS-D was 7.3 ± 4.0 (median 7.5; range 1-15). Using conventional cut-offs, HADS-A scores were distributed as follows: 0-7 (non-case): 8/18 patients (44.4%); 8-10 (borderline/at risk): 1/18 (5.6%); ≥ 11 (clinically significant anxiety): 9/18 (50.0%). For HADS-D, the distribution was: 0-7 (non-case): 9/18 patients (50.0%); 8-10 (borderline/at risk): 6/18 (33.3%); ≥ 11 (clinically significant depression): 3/18 (16.7%).

Overall, 11 of 18 patients (61.1%) scored in the borderline or clinical range (≥ 8) on at least one HADS subscale. Clinically significant anxiety (HADS-A ≥ 11) was present in half of the sample. In contrast, clinically significant de

Mean SF-12 PCS score was 35.8 ± 10.9 (median 35.5; range 19-52.4), indicating, on average, a clear reduction in physical health-related quality of life compared with general population norms. Most patients had substantially impaired physical functioning: PCS ≥ 50: 3/18 (16.7%); PCS 40-49.9: 3/18 (16.7%); PCS 30-39.9: 5/18 (27.8%); PCS < 30: 7/18 (38.9%).

Thus, 12/18 patients (66.7%) had PCS scores < 40, and 7/18 (38.9%) had scores < 30, compatible with marked limi

Mean SF-12 MCS score was 41.3 ± 12.3 (median 42.5; range 24-60.6). Mental health-related quality of life was more heterogeneous than physical functioning, with the following distribution: MCS ≥ 50: 6/18 (33.3%); MCS 40-49.9: 4/18 (22.2%); MCS 30-39.9: 4/18 (22.2%); MCS < 30: 4/18 (22.2%).

Overall, 8/18 patients (44.4%) had MCS scores < 40, and 4/18 (22.2%) had MCS scores < 30, indicating moderate-to-severe impairment in mental quality of life in a substantial minority of the sample. In several cases, very low PCS scores coexisted with only mildly reduced or near-normal MCS scores. In contrast, in others, severely reduced MCS scores accompanied clinically significant anxiety and/or depressive symptoms. The median (IQR) scores were: HADS-A 9.5 (5.3-12.8), HADS-D 7.5 (3.8-9.8), SF-12 PCS 35.5 (26.0-43.5), and SF-12 MCS 42.5 (30.3-50.8). Exploratory correlation studies revealed that increased anxiety and depressive symptomatology correlated with poorer mental health-related quality of life: Spearman’s rho was -0.66 for HADS-A compared to SF-12 MCS (P = 0.003) and -0.74 for HADS-D compared to SF-12 MCS (P < 0.001). The correlations with SF-12 PCS were weak and not statistically significant in this pilot group (HADS-A vs PCS rho = -0.10; HADS-D vs PCS rho = -0.18).

Based on the integrated evaluation (ophthalmologic review, HADS, SF-12, and clinical interview), the psychologist formulated a brief psychological profile and a recommendation regarding follow-up for each patient. Seven patients (38.9%) were judged not to require urgent psychological intervention and were assigned to monitoring and/or optional support. This group included patients with minimal or borderline symptoms, relatively preserved coping strategies, and no major functional impairment, despite chronic disease.

Nine patients (50.0%) received a recommendation for structured psychological support or psychotherapy (e.g., in

Two patients (11.1%) were flagged for more in-depth psychological and psychiatric evaluation, due to high HADS scores in both anxiety and depression, markedly reduced MCS scores, and complex clinical pictures (e.g., profound discouragement, guilt or self-blame, possible eating or other comorbid disorders).

In summary, in this small but clinically complex sample, systematic use of HADS and SF-12 alongside a semi-structured clinical interview revealed a high prevalence of anxiety symptoms, frequent borderline depressive symptoms, markedly reduced physical quality of life, and heterogeneous but often impaired mental quality of life. These findings directly informed the clinical decision to recommend some form of psychological or psychotherapeutic follow-up in half of the patients and to consider a specialized psychiatric opinion in a further subset. Table 1 summarizes the main socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the case series, together with ocular findings, Dry Eye status, brief psychological profiles, HADS anxiety/depression scores, SF-12 physical/mental component scores, and the resulting psychological judgement.

This psycho-ophthalmology case series highlights a substantial burden of psychological distress and functional im

A clinically salient theme in our cohort was the subjective symptom burden associated with ocular surface disease, particularly dry eye, and how patients described its interaction with stress, sleep disturbance, fatigue, and pain during the clinical interview. Although our case series is not designed to test associations and clinically significant anxiety was observed both in patients with and without dry eye, several individuals with dry eye spontaneously reported feedback loops in which burning, photophobia, fluctuating vision, and activity restrictions (e.g., prolonged screen use, outdoor exposure) contributed to worry and social withdrawal, with subsequent perceived exacerbation of ocular discomfort. This pattern is consistent with the broader literature showing that DED is associated with increased odds of depressive and anxiety symptoms, and that psychological distress tends to correlate more strongly with patient-reported symptom severity than with traditional tear film signs (e.g., tear break-up time, Schirmer’s test, corneal staining)[10,29,30].

In practical terms, these narratives support the clinical usefulness of brief screening, coupled with targeted psychoeducation on symptom-stress interactions, pacing, sleep hygiene, and pain-coping strategies, as part of an integrated management approach, especially in autoimmune contexts, where ocular surface symptoms often coexist with systemic fatigue and pain. Our clinical interviews echoed these quantitative findings: Several patients spontaneously described vicious circles in which pain, photophobia, and functional restrictions (e.g., limiting screen use, avoiding outdoor activities) fueled social withdrawal and worry, which in turn amplified the perceived burden of ocular symptoms. Given the descriptive nature of the study and the small, heterogeneous sample, we did not perform subgroup comparisons (e.g., dry eye vs non-dry eye), and all disease-specific observations should be interpreted as clinically grounded signals rather than inferential findings.

Within this group, individuals with Sjögren’s disease and other connective tissue disorders appeared particularly vulnerable. Cross-sectional data from specialist clinics show that primary Sjögren’s syndrome is associated with substantially reduced generic and oral health-related quality of life, prominent fatigue and pain, and a high prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms compared with healthy controls in predominantly female cohorts[31]. Additional clinic-based studies using SF-36, Beck Depression Inventory, and Rosenberg self-esteem scale indicate that quality of life in Sjögren’s is impaired across all domains, with depressive symptoms present in more than half of patients and significantly correlated with disease activity indices[32]. In our cohort, patients with Sjögren’s and overlapping connective tissue disease similarly reported chronic fatigue, pain, sleep disturbance, and concerns about future independence, often in the context of dry eye and other ocular manifestations. These narratives are consistent with work on systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases more broadly, where illness-related uncertainty and fluctuating, often invisible symptoms have been linked to higher levels of anxiety and depression and to greater illness-related impact on daily life, beyond what is captured by biomedical measures alone[33].

A second theme emerging from this series is the psychosocial impact of rare and uncommon ophthalmic conditions, including inherited optic neuropathies, retinitis pigmentosa, and cicatricial pemphigoid with corneal complications. Patients in these groups frequently described fear of blindness, loss of valued roles, and difficulties maintaining work or social participation. These accounts are consistent with quantitative evidence that visual impairment is associated with elevated symptoms of depression and anxiety and reduced HRQoL. In children and adolescents, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed that vision impairment is linked to significantly higher depression and anxiety scores than in normally sighted peers, and that surgical treatment of strabismus can ameliorate these symptoms[34].

Longitudinal, population-based data in adults similarly indicate that registered visual impairment confers an increased hazard of incident depression, with a higher risk in those with blindness compared with milder visual loss[35]. Among neuro-ophthalmic and low-vision clinic populations, cross-sectional surveys have reported a high proportion of patients with at least mild symptoms of depression and anxiety, often correlating with the severity of visual impairment, leading some authors to advocate routine psychological screening in these settings[1,2]. Although our sample size is small and not restricted to low-vision patients, the qualitative accounts of fear of future blindness, social withdrawal, and altered self-image mirror these findings and suggest that similar mechanisms may operate across different rare and vision-threatening eye diseases.

Our findings also align with rheumatology data showing that, in rheumatoid arthritis and other systemic autoimmune diseases, comorbid depression and anxiety are independently associated with poorer HRQoL, and remain significant predictors even after adjustment for pain, disability, and medical comorbidity[28]. Consistent with this, a recent analysis from the United Kingdom on future health cohort (over 1.5 million adults) reported that individuals with autoimmune conditions had a higher lifetime and current prevalence of depression, anxiety and bipolar disorder (for example, 28.8% vs 17.9% for any affective disorder), with the odds of affective disorders remaining elevated despite controlling for sociodemographic variables, parental history of affective disorders, chronic pain and social isolation[36]. These data support the hypothesis that chronic systemic inflammation and the cumulative burden of autoimmune illness may increase vulnerability to affective symptoms. In our cohort, many participants explicitly linked emotional deterioration to systemic flares, prolonged diagnostic delays, or the weight of multiple autoimmune diagnoses in themselves and close relatives, reinforcing the need to situate ophthalmic disease within a wider systemic and psychosocial context.

From a service-delivery perspective, this case series offers practice-based support for the emerging field of psycho-ophthalmology and for the application of consultation-liaison models within eye care. Narrative and scoping reviews have shown that psychological distress-including anxiety, depression, stress, and suicidal ideation-is highly prevalent among people with visual impairment. At the same time, emotional needs remain frequently under-recognized, and access to structured, non-pharmacological interventions is limited in routine ophthalmic services[6,37]. Building on this evidence, a recent narrative review has synthesized data across DED, cataract, glaucoma, age-related macular de

Crucially, referral decisions in our setting were not based solely on questionnaire scores. The integrated model allowed clinicians to weigh HADS and SF-12 results against qualitative information such as burnout, bereavement, diagnostic uncertainty, family dynamics, or probable disordered eating. In several cases, patients with only borderline scores were nevertheless prioritized for psychological follow-up because their narrative and behavioral patterns suggested hei

These findings have concrete implications for psychiatrists and psychologists working with rare and autoimmune diseases. First, our experience suggests that regular, low-burden screening for anxiety and depression in ophthalmic clinics is both feasible and clinically informative, particularly in patients with dry eye, systemic autoimmune disease, or rare vision-threatening conditions, where epidemiological and review data indicate elevated rates of mood and anxiety symptoms[39]. Second, the pattern of complaints observed in our cohort highlights the potential value of brief psy

From a pragmatic perspective, HADS and SF-12 can be seamlessly incorporated into standard autoimmune/complex ophthalmology consultations with negligible disruption. Patients can complete both instruments in the waiting area or electronically prior to the appointment, generally taking only a few minutes, and they can be rated promptly using defined criteria. In a stepped-care framework, established thresholds (e.g., HADS-A or HADS-D ≥ 11; borderline scores with functional impairment; significantly diminished SF-12 MCS) may initiate a concise, targeted discussion regarding distress and coping strategies, subsequently leading to referral options that encompass psychoeducation and monitoring, as well as structured psychological interventions or psychiatric consultations. This strategy does not necessitate ophthalmologists to render psychiatric diagnoses; instead, it facilitates the early identification of patients who may require prompt mental health intervention.

At the same time, several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. This paper serves as a preliminary, practice-oriented description of a newly established integrated psycho-ophthalmology pathway; hence, the findings are ex

The sample is small, single-center, and clinically heterogeneous, reflecting referrals to a tertiary clinic rather than a representative cross-section of ophthalmic practice; therefore, quantitative findings cannot be generalized. The design is descriptive and cross-sectional so that no inference can be drawn about causal or temporal relationships among ocular disease, systemic inflammation, and psychological symptoms. We relied on brief screening tools (HADS and SF-12) rather than structured psychiatric interviews, and we therefore cannot provide formal diagnostic rates for depressive or anxiety disorders. In addition, we did not systematically collect follow-up data on psychological or psychotherapeutic in

These limitations point to several future directions. Future research should include comparators and longitudinal follow-up to enhance inference. A viable methodology may involve matched control groups, including: (1) Patients with chronic non-autoimmune ocular conditions (e.g., cataract follow-up, refractive disorders, non-inflammatory retinal diseases) matched by age and sex; and/or (2) Healthy individuals recruited from hospital personnel or community en

The prioritization of interventional evaluation is essential. A pragmatic randomized controlled trial may evaluate standard ophthalmology care against standard care supplemented with an integrated psycho-ophthalmology package (screening, brief psychoeducation, and expedited access to psychological support), measuring outcomes such as HADS, SF-12, treatment adherence, appointment attendance, and patient-reported symptom burden over a period of 3 months to 12 months. A prospective cohort using a stepped-care algorithm could evaluate whether early low-intensity therapies (psychoeducation, coping and sleep modules, pain-focused methods) reduce the need for high-intensity care and improve mental HRQoL. Such designs will maintain practical applicability while providing stronger evidence of clinical efficacy and scalability.

Building on this pilot experience, larger prospective studies are needed to better characterize the prevalence, course, and predictors of anxiety and depression in patients with autoimmune and rare ophthalmic diseases. Sample expansion would allow stratified analyses by diagnosis (e.g., Sjögren’s, scleroderma, inflammatory eye disease, inherited optic neuropathies) and by key clinical variables such as disease duration, degree of visual impairment, and treatment ex

In summary, our case series confirms that high levels of anxiety, frequent depressive symptoms, and substantial physical impairment are clinically significant features of patients with autoimmune and rare ophthalmic conditions. These findings mirror and extend the existing rheumatology and ophthalmology literature and support integrating mental health assessment into eye care as a practical, clinically meaningful component of comprehensive management. An overview of the cohort, the integrated pathway, and the main outcomes (HADS and SF-12) is presented in Figure 1.

Patients living with autoimmune, inflammatory, and rare ophthalmic diseases face a substantial and often under-re

Our experience also shows that systematic screening with brief standardized instruments such as the HADS and SF-12 is both feasible and informative in routine ophthalmic practice. Administered alongside a focused semi-structured clinical interview, these tools provided a shared language between ophthalmologists and psychologists, helped to identify patients with clinically relevant anxiety or depressive symptoms, and directly informed decisions regarding psychological support, psychotherapy, or psychiatric referral. Importantly, referral decisions were based on an integrated ap

Although limited by its small size, single-center design, and descriptive nature, this pilot case series offers a pragmatic model for embedding mental health assessment within ophthalmology services that care for patients with rare and autoimmune eye diseases. Future prospective and interventional studies with larger samples are needed to clarify the prevalence, course, and predictors of psychiatric comorbidity in this group, and to test whether targeted psychological or psychoeducational interventions can improve both mental health and ophthalmic outcomes. In the meantime, our data support the routine consideration of emotional distress, coping, and quality of life as integral components of comprehensive care for patients with complex autoimmune ophthalmology.

| 1. | Demmin DL, Silverstein SM. Visual Impairment and Mental Health: Unmet Needs and Treatment Options. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:4229-4251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Virgili G, Parravano M, Petri D, Maurutto E, Menchini F, Lanzetta P, Varano M, Mariotti SP, Cherubini A, Lucenteforte E. The Association between Vision Impairment and Depression: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Studies. J Clin Med. 2022;11:2412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Parravano M, Petri D, Maurutto E, Lucenteforte E, Menchini F, Lanzetta P, Varano M, van Nispen RMA, Virgili G. Association Between Visual Impairment and Depression in Patients Attending Eye Clinics: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139:753-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ulhaq ZS, Soraya GV, Dewi NA, Wulandari LR. The prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders among ophthalmic disease patients. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2022;14:25158414221090100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jesus J, Ambrósio J, Meira D, Rodriguez-Uña I, Beirão JM. Blinded by the Mind: Exploring the Hidden Psychiatric Burden in Glaucoma Patients. Biomedicines. 2025;13:116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mamtani NH, Mamtani HG, Chaturvedi SK. Psychiatric aspects of ophthalmic disorders: A narrative review. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023;71:1810-1815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vasanthakumar A, Sathyanath S, Kakunje A, Nishad PMA. Psycho-ophthalmology: A detailed review. Muller J Med Sci Res. 2024;15:48-55. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Sadykov E, Studnička J, Hosák L, Siligardou MR, Elfurjani H, Hoikam JL, Kugananthan S, Petrovas A, Amjad T. The Interface Between Psychiatry and Ophthalmology. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove). 2019;62:45-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Basilious A, Xu CY, Malvankar-Mehta MS. Dry eye disease and psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2022;32:1872-1889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wan KH, Chen LJ, Young AL. Depression and anxiety in dry eye disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eye (Lond). 2016;30:1558-1567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Di Zazzo A, De Gregorio C, Spelta S, Demircan S. Mental burden of ocular surface discomfort. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2025;35:1445-1455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cui B, Jia HZ, Gao LX, Dong XF. Risk of anxiety and depression in patients with uveitis: a Meta-analysis. Int J Ophthalmol. 2022;15:1381-1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Abdel-Aty A, Kombo N. The Association Between Mental Health Disorders and Non-Infectious Scleritis: A Prevalence Study and Review of the Literature. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2022;32:1850-1856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vakros G, Scollo P, Hodson J, Murray PI, Rauz S. Anxiety and depression in inflammatory eye disease: exploring the potential impact of topical treatment frequency as a putative psychometric item. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2021;6:e000649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Prem Senthil M, Khadka J, Pesudovs K. Assessment of patient-reported outcomes in retinal diseases: a systematic review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2017;62:546-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Prem Senthil M, Khadka J, Gilhotra JS, Simon S, Pesudovs K. Exploring the quality of life issues in people with retinal diseases: a qualitative study. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2017;1:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Li Y, Zhao C, Sun S, Mi G, Liu C, Ding G, Wang C, Tang F. Elucidating the bidirectional association between autoimmune diseases and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Ment Health. 2024;27:e301252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Covic T, Cumming SR, Pallant JF, Manolios N, Emery P, Conaghan PG, Tennant A. Depression and anxiety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: prevalence rates based on a comparison of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) and the hospital, Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Matcham F, Ali S, Irving K, Hotopf M, Chalder T. Are depression and anxiety associated with disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis? A prospective study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hattori Y, Katayama M, Kida D, Kaneko A. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Score Is an Independent Factor Associated With the EuroQoL 5-Dimensional Descriptive System in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2018;24:308-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Del Rosso A, Mikhaylova S, Baccini M, Lupi I, Matucci Cerinic M, Maddali Bongi S. In systemic sclerosis, anxiety and depression assessed by hospital anxiety depression scale are independently associated with disability and psychological factors. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:507493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cui Y, Xia L, Li L, Zhao Q, Chen S, Gu Z. Anxiety and depression in primary Sjögren's syndrome: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hurst NP, Ruta DA, Kind P. Comparison of the MOS short form-12 (SF12) health status questionnaire with the SF36 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:862-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gandhi SK, Salmon JW, Zhao SZ, Lambert BL, Gore PR, Conrad K. Psychometric evaluation of the 12-item short-form health survey (SF-12) in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1080-1098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dritsaki M, Petrou S, Williams M, Lamb SE. An empirical evaluation of the SF-12, SF-6D, EQ-5D and Michigan Hand Outcome Questionnaire in patients with rheumatoid arthritis of the hand. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28548] [Cited by in RCA: 32891] [Article Influence: 764.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11319] [Cited by in RCA: 13236] [Article Influence: 441.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Alwhaibi M. Depression, Anxiety, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Rheumatoid Arthritis: Findings from a National Survey. J Clin Med. 2025;14:7940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Vieira GCF, Rodrigues BRO, Cunha CEXD, Morais GB, Ferreira LHRM, Ribeiro MVMR. Depression and dry eye: a narrative review. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2021;67:462-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tsai CY, Jiesisibieke ZL, Tung TH. Association between dry eye disease and depression: An umbrella review. Front Public Health. 2022;10:910608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Al-Ezzi MY, Khan KS, Tappuni AR. Quality of Life and Mental Health Well-Being in Sjögren's Disease in the UK: A Cross-Sectional Comparative Analysis. J Clin Med. 2025;14:1939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ramia T, Daada S, Chaabene I, Klii R, Hammami S, Ines K, Kechida M. AB0539 depression, self-esteem and quality of life in Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:1397. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Piper MA, Tunks A, Humfrey S, Calderwood L, Tayabali S, Taylor S, Kaul A, Dalby E, Ahmed S, Farrington S, Pollak TA, Sloan M. "My world has shrunk": a mixed-methods exploration of the impact of systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases on patients' lives. Rheumatol Int. 2025;45:247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Li D, Chan VF, Virgili G, Piyasena P, Negash H, Whitestone N, O'Connor S, Xiao B, Clarke M, Cherwek DH, Singh MK, She X, Wang H, Boswell M, Prakalapakorn SG, Patnaik JL, Congdon N. Impact of Vision Impairment and Ocular Morbidity and Their Treatment on Depression and Anxiety in Children: A Systematic Review. Ophthalmology. 2022;129:1152-1170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Choi HG, Lee MJ, Lee SM. Visual impairment and risk of depression: A longitudinal follow-up study using a national sample cohort. Sci Rep. 2018;8:2083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Mudra Rakshasa-Loots A, Swiffen D, Steyn C, Marwick KFM, Smith DJ. Affective disorders and chronic inflammatory conditions: analysis of 1.5 million participants in Our Future Health. BMJ Ment Health. 2025;28:e301706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Thurston M, Warden R, Thurston C, Hawkins A, Bird H. The Mental Health of People With Visual Impairments and Related Interventions: A Scoping Review From 2016 to 2023. J Visual Impair Blin. 2025;119:392-405. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 38. | Tang WSW, Lau NXM, Krishnan MN, Chin YC, Ho CSH. Depression and Eye Disease-A Narrative Review of Common Underlying Pathophysiological Mechanisms and their Potential Applications. J Clin Med. 2024;13:3081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 39. | Alkozi HA. Ocular Surface Health in Connection with Anxiety and Depression: a Review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2024;17:2671-2676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Wallace ZS, Cook C, Finkelstein-Fox L, Fu X, Castelino FV, Choi HK, Perugino C, Stone JH, Park ER, Hall DL. The Association of Illness-related Uncertainty With Mental Health in Systemic Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases. J Rheumatol. 2022;49:1058-1066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/