Published online Feb 6, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i4.117573

Revised: December 29, 2025

Accepted: January 23, 2026

Published online: February 6, 2026

Processing time: 57 Days and 2.7 Hours

Cefepime is a fourth-generation cephalosporin antibiotic widely used to treat a variety of serious bacterial infections, including febrile neutropenia, pneumonia, complicated intra-abdominal infections, urinary tract infections, and skin infe

We report the case of a 73-year-old male who presented to the emergency de

This case report highlights a rare adverse effect of a commonly used antimicrobial in the hospital setting for various bacterial infections. Prompt cessation of the medication is the primary treatment in cefepime-induced liver injury, and most cases resolve without complications.

Core Tip: Cefepime is a fourth-generation cephalosporin commonly used to treat various bacterial infections. It is safe and generally well-tolerated. While frequently associated with adverse effects such as neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity, cases of hepatotoxicity are rare. Prompt cessation of the medication is the primary approach in management.

- Citation: Garcia R, English K. Mixed hepatocellular-cholestatic liver injury from cefepime: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(4): 117573

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i4/117573.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i4.117573

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) commonly occurs in the hospital setting with several classes of medication. The ap

Cough, shortness of breath, and fatigue.

A 73-year-old male arrived to the emergency department (ED) due to a 1-week history of shortness of breath, cough with greenish sputum, and worsening fatigue. The patient was seen by his pulmonologist for a routine visit, who subsequently recommended ED evaluation for his symptoms. On arrival to the ED, vital signs were within normal limits.

His medical history included hypothyroidism, gastroesophageal reflux disease, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, atopic dermatitis, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and bronchiectasis.

No personal or family history.

Physical examination revealed an ill-appearing, cachectic man in mild distress who responded to questions adequately. S1 and S2 heart sounds were present with normal rate and rhythm. Lung auscultation revealed coarse referred airway sounds throughout the bilateral lung fields, more greatly appreciated on the right. The abdomen was soft and non-tender to palpation, and extremities were symmetric without edema.

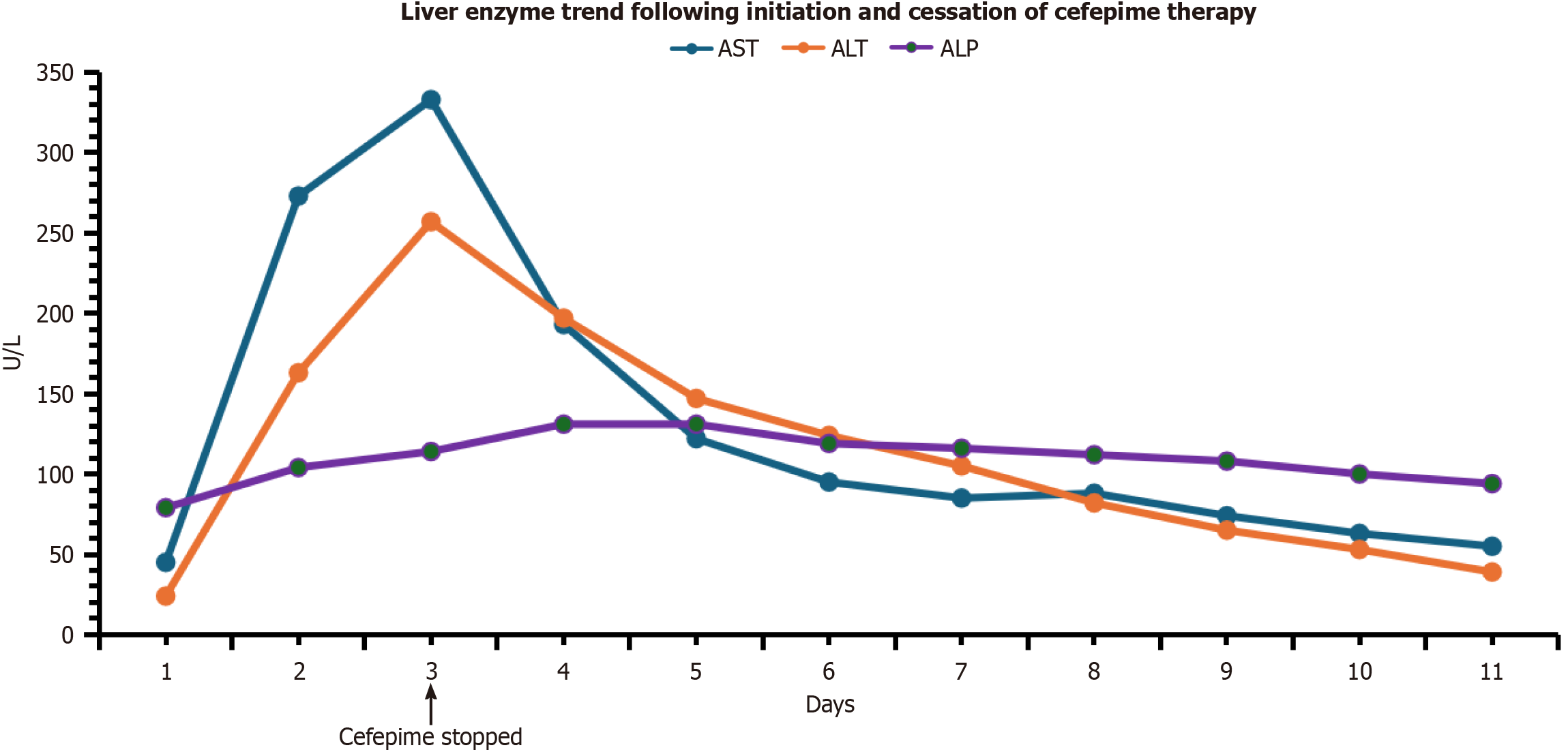

Laboratory tests in the ED revealed leukocytosis (white blood cells 11.9/mm3), hypoglycemia (72), hyponatremia (129 mmol/L), hyperbilirubinemia (1.8 mg/dL), and elevated procalcitonin (1.395 ng/mL). All other values, such as coagulation profile, blood gas, creatinine clearance, and liver function tests (LFTs) [aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 45 U/L and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 24 U/L] were within normal limits. A respiratory pathogen panel detected rhinovirus and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus were present in the nares. Blood cultures were negative. Sputum culture drawn ultimately revealed Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Liver enzymes (Figure 1) subse

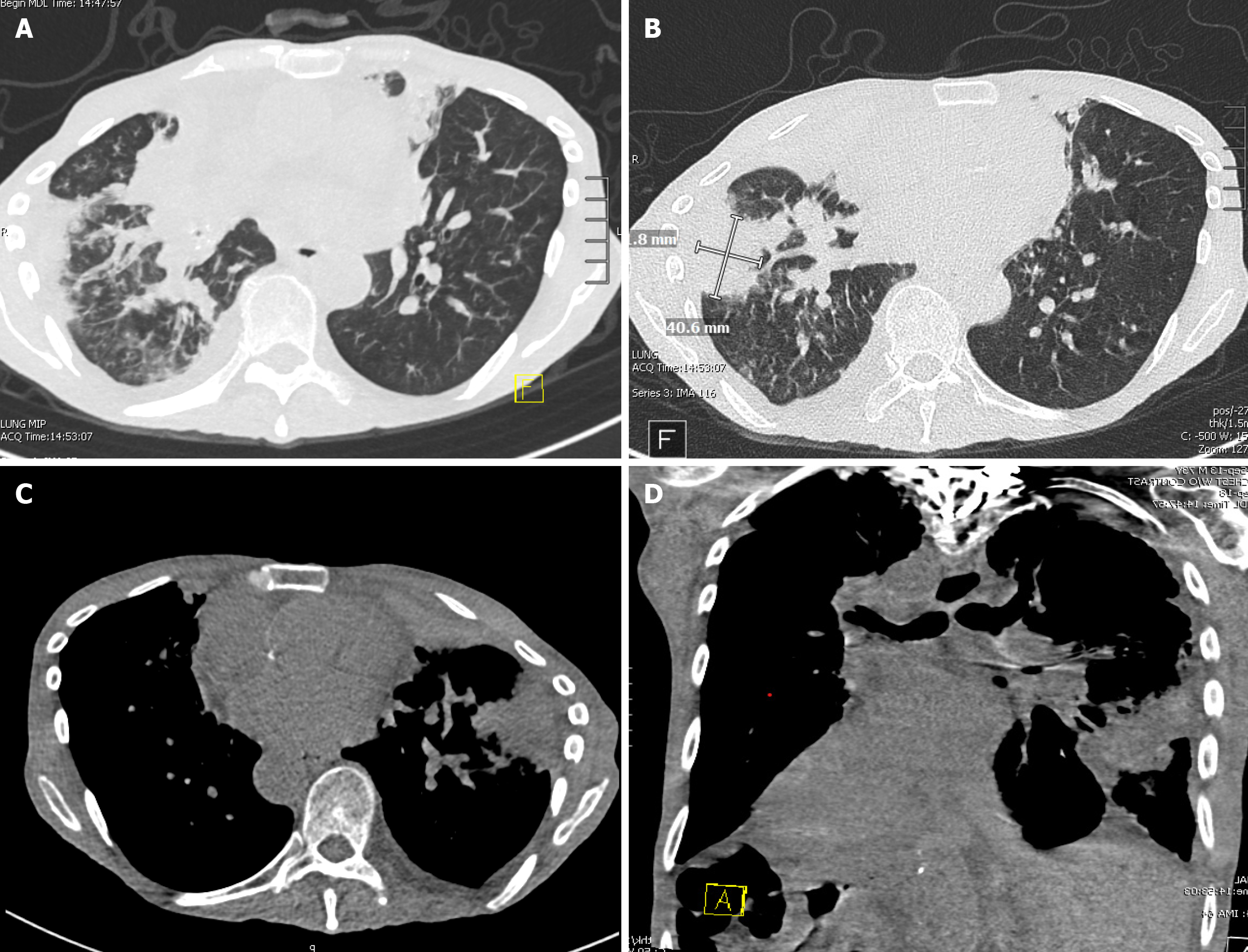

A computed tomography scan of the chest without contrast was done on arrival, which showed new and worsening consolidative opacities in both lungs, extensive airway thickening with numerous occluded bronchi, and a new right-sided pleural effusion (Figure 2). A right upper quadrant ultrasound was done on the following day due to worsening LFTs, which showed nonspecific hepatitis.

Cefepime-induced mixed hepatocellular-cholestatic liver injury.

The patient was hospitalized, where he was initiated on vancomycin and cefepime for infected bronchiectasis. AST and ALT were elevated the following day and continued to worsen, prompting cessation of cefepime and a transition to piperacillin-tazobactam for continued management. Vancomycin was continued.

LFTs ultimately trended to baseline normal values within 11 days after cefepime cessation. He ultimately died from acute hypoxic respiratory failure two weeks after admission.

Cefepime, an antibiotic wide-spectrum antibacterial activity, is considered safe with few side effects[1-4]. Although the medication has been linked to incidences of nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity, DILI is uncommon[9,10]. A precise di

Our patient in this case developed hepatic injury as noted above within 24 hours of starting cefepime therapy (2 g every 8 hours). The causal relationship between cefepime and DILI was assessed using the Naranjo adverse drug reaction probability scale[15,16]. This accountability scale encompasses various criteria, including the time link between drug exposure and the onset of liver damage, the progression of liver enzymes after discontinuation of the drug, prior case documentation of DILI, concurrent medications, and other potential causes that might have led to the reaction. In our case, the Naranjo score (Table 1) was 7 on a scale of 0 to 12, with a score of ≥ 9 indicating that the drug was the likely cause of the reaction. The score of 7 correlated with the probable category. Some questions on the probability scale, such as “Was the drug detected in any body fluid in toxic concentrations”? were not feasible to answer, which partially accounted for the observed lower score. Other causes of liver injury were ruled out. Testing for hepatitis A, B, and C with a hepatitis panel was negative. Additional serological testing included EBV, CMV, anti-smooth muscle, and anti-liver-kidney microsomal-1 antibodies, all of which were negative. Other drugs as a culprit of liver injury were also ruled out, as the patient was not taking any medications that are commonly associated with liver injury. Vancomycin, which can occasionally cause hepatoxicity, was continued despite the cessation of cefepime, ruling it out as a confounding factor. Transaminitis ultimately improved with cessation of drug therapy, and LFTs went back to baseline.

| Question | Yes | No | Do not know | Score |

| Are there previous conclusive reports on this reaction? | +1 | 0 | 0 | +1 |

| Did the adverse event appear after the suspected drug was administered? | +2 | -1 | 0 | +2 |

| Did the adverse reaction improve when the drug was discontinued, or a specific antagonist was administered? | +1 | 0 | 0 | +1 |

| Did the adverse reaction reappear when the drug was readministered? | +2 | -1 | 0 | 0 |

| Are there alternative causes (other than the drug) that could on their own have caused the reaction? | -1 | +2 | 0 | +2 |

| Did the reaction reappear when a placebo was given? | -1 | +1 | 0 | 0 |

| Was the drug detected in the blood (or other fluids) in concentrations known to be toxic? | +1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Was the reaction more severe when the dose was increased or less severe when the dose was decreased? | +1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Did the patient have a similar reaction to the same or similar drugs in any previous exposure? | +1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Was the adverse event confirmed by any objective evidence? | +1 | 0 | 0 | +1 |

| Total score | 7 | |||

Cefepime-induced liver injury is rare but commonly presents as cholestatic or mixed hepatocellular-cholestatic hepatitis, often resembling an immune-mediated reaction with rash, eosinophilia, and fever, though the precise me

In summary, our case illustrates a rare but true hepatotoxicity associated with cefepime therapy. Although cefepime is usually well-tolerated, it can lead to DILI especially in older patients with comorbid conditions. This article underscores the importance of careful monitoring of liver enzymes in patients receiving cefepime therapy. Worsening LFTs typically occur prior to symptoms and prompt cessation of therapy is important in preventing the development of fulminant liver failure and chronic liver disease. Clinicians should be aware of this rare adverse effect and intervene with medication cessation when necessary.

| 1. | Björnsson ES. The Epidemiology of Newly Recognized Causes of Drug-Induced Liver Injury: An Update. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;17:520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Björnsson ES, Bergmann OM, Björnsson HK, Kvaran RB, Olafsson S. Incidence, presentation, and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1419-1425, 1425.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 535] [Cited by in RCA: 606] [Article Influence: 46.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li X, Tang J, Mao Y. Incidence and risk factors of drug-induced liver injury. Liver Int. 2022;42:1999-2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Leise MD, Poterucha JJ, Talwalkar JA. Drug-induced liver injury. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:95-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Andrade RJ, Lucena MI, Fernández MC, Pelaez G, Pachkoria K, García-Ruiz E, García-Muñoz B, González-Grande R, Pizarro A, Durán JA, Jiménez M, Rodrigo L, Romero-Gomez M, Navarro JM, Planas R, Costa J, Borras A, Soler A, Salmerón J, Martin-Vivaldi R; Spanish Group for the Study of Drug-Induced Liver Disease. Drug-induced liver injury: an analysis of 461 incidences submitted to the Spanish registry over a 10-year period. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:512-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 722] [Cited by in RCA: 702] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | De Valle MB, Av Klinteberg V, Alem N, Olsson R, Björnsson E. Drug-induced liver injury in a Swedish University hospital out-patient hepatology clinic. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1187-1195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yahav D, Paul M, Fraser A, Sarid N, Leibovici L. Efficacy and safety of cefepime: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:338-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Maan G, Keitoku K, Kimura N, Sawada H, Pham A, Yeo J, Hagiya H, Nishimura Y. Cefepime-induced neurotoxicity: systematic review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2022;77:2908-2921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liao PF, Wu YK, Huang KL, Chen HY. A rare case of cefepime-induced cholestatic liver injury. Tzu Chi Med J. 2019;31:124-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Malhotra K, Fazylov R, Friedman-Jakubovics M. A Case-Report of Drug-Induced Mixed Liver Injury Resulting From Cefepime Exposure. J Pharm Pract. 2023;36:164-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Alqahtani SA, Kleiner DE, Ghabril M, Gu J, Hoofnagle JH, Rockey DC; Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) Study Investigators. Identification and Characterization of Cefazolin-Induced Liver Injury. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1328-1336.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Reuben A, Koch DG, Lee WM; Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Drug-induced acute liver failure: results of a U.S. multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2010;52:2065-2076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 515] [Cited by in RCA: 538] [Article Influence: 33.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Grewal P, Ahmad J. Beware of HCV and HEV in Patients with Suspected Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Curr Hepatol Rep. 2018;17:270-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ghabril M, Gu J, Yoder L, Corbito L, Ringel A, Beyer CD, Vuppalanchi R, Barnhart H, Hayashi PH, Chalasani N. Development and Validation of a Model Consisting of Comorbidity Burden to Calculate Risk of Death Within 6 Months for Patients With Suspected Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:1245-1252.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, Janecek E, Domecq C, Greenblatt DJ. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7061] [Cited by in RCA: 8477] [Article Influence: 188.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 16. | Murali M, Suppes SL, Feldman K, Goldman JL. Utilization of the Naranjo scale to evaluate adverse drug reactions at a free-standing children's hospital. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0245368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Devarbhavi HC, Andrade RJ. Natural History of Idiosyncratic Drug-Induced Liver Injury and Prognostic Models. Liver Int. 2025;45:e70138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/