Published online Feb 6, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i4.116737

Revised: December 19, 2025

Accepted: January 21, 2026

Published online: February 6, 2026

Processing time: 77 Days and 18.9 Hours

Accurate preoperative assessment of physical function is vital for determining surgical indications and selecting appropriate procedures in older adults. In potentially malignant cases of giant ovarian tumors, tumor capsule intraoperative rupture can cause upstaging and increase malignant ovarian tumor recurrence risk; thus, avoiding it is essential.

An 81-year-old woman with a giant ovarian tumor underwent preoperative eva

Detailed preoperative evaluation and the Aron alpha method could assist older women with giant ovarian tumors, with suspected malignancy.

Core Tip: When planning surgical treatment for elderly patients, their overall health and postoperative risks must be appropriately assessed using the estimation of physiologic ability and surgical stress scoring system and the FRAIL scale. Accordingly, the treatment plan and perioperative management may be implemented using the enhanced recovery after surgery protocol. Furthermore, the Aron alpha method for giant ovarian tumors enables minimal invasive surgery without leaking the ovarian tumor contents into the abdominal cavity. This surgical technique helps elderly patients with giant ovarian tumors of uncertain malignancy.

- Citation: Segawa A, Kakinuma T, Miyazawa C, Takeuchi J, Tamura M, Morita A, Takae S, Suzuki N, Ariizumi Y. Successful perioperative management for a giant ovarian tumor in older adults: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(4): 116737

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i4/116737.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i4.116737

With the recent aging of the population, opportunities to perform surgery on older adults have been increasing. In general, older adults tend to have reduced physiologic reserve, impaired wound healing ability, weakened immune function, and comorbidities. As a result, postoperative complications are more likely to occur, and when severe, they can have a significant impact on prognosis[1-3]. Postoperative complications in older adults are directly associated with prolonged hospitalization, decreased quality of life, and increased economic burden. However, advances in perioperative care, surgical techniques, and anesthesia management in recent years have contributed to a decline in surgical mortality among older adults, and age alone is no longer considered a risk factor[4,5]. Moreover, because actual age and biological age do not necessarily coincide, the response to surgical stress and postoperative outcomes must be assessed individually for each case[6]. Therefore, prior to perioperative management, it is crucial to rigorously assess physiologic reserve and determine whether the patient can tolerate the planned anesthesia and surgical stress. Efforts to reduce perioperative risk should not focus solely on individual organ function but also include a comprehensive assessment of frailty, delirium, polypharmacy, and nutritional status. As part of preoperative evaluation, tools such as the estimation of physiologic ability and surgical stress (E-PASS) scoring system have been used to quantify patients’ physiological function and surgical stress, thereby predicting postoperative complications and in-hospital mortality to assess surgical risk (Table 1)[3,4]. Proposed by Haga et al[7] in 1999, the E-PASS system is based on commonly available laboratory and surgical pa

| Calculation of preoperative risk, surgical stress, and comprehensive risk scores |

| Score formula |

| PRS: -0.0686 + 0.00345X1 + 0.323X2 + 0.205X3 + 0.153X4 + 0.148X5 + 0.0666X6 |

| SSS: -0.342 + 0.0139Y1 + 0.0392Y2 + 0.352Y3 |

| CRS: -0.328 + 0.936 (PRS) + 0.976 (SSS) |

| Age, serious heart disease, serious pulmonary disease, and diabetes mellitus are defined as present 1 or absent 0 |

| PRS, X1 age, X2 serious heart disease, X3 serious pulmonary disease, X4 diabetes mellitus, X5 performance status (0-4), X6 ASA score (1-5), SSS, Y1 blood loss/body weight (g/kg), Y2 operating time (hour), Y3 skin incision length (0: Minor incision, 1: Laparotomy or thoracotomy only, 2: Laparotomy and thoracotomy) CRS |

Frailty has been reported to heighten sensitivity to surgical and anesthetic stress, increase postoperative complications, and prolong hospitalization; thus, preoperative frailty assessment is important[11]. The FRAIL scale has been reported to be a simple and versatile tool for assessing frailty in older surgical patients[12].

For perioperative management, the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol encompasses evidence-based strategies to reduce patient anxiety and discomfort, minimize postoperative complications, shorten hospital stays through early recovery, and lower medical costs. Implementation of the ERAS protocol has been reported to reduce postoperative complications, shorten postoperative hospital stays, and decrease the financial burden on patients[13-16].

Furthermore, in cases of giant ovarian tumors, preoperative differentiation between benign and malignant lesions is often difficult, and some cases are ultimately diagnosed as malignant in the final pathological examination. When an ovarian tumor is malignant, intraoperative rupture of the tumor capsule poses a risk of disease upstaging[17] and in

In this report, we present a case of a giant ovarian tumor in an older adult who underwent preoperative evaluation using the E-PASS scoring system and the FRAIL scale, followed by laparoscopy-assisted surgery with the Aron alpha method, and perioperative management under the ERAS protocol, which collectively resulted in a favorable outcome. We obtained informed consent both verbally and in writing.

Age: 81 years. Abdominal distension.

The patient noticed abdominal distension for the previous 3 months and consulted a physician. An abdominal mass reaching the level of the umbilicus was detected, and she was referred to our hospital for further evaluation and treatment. She visited our outpatient clinic, walking with a cane, but was independent in activities of daily living (ADL).

Subarachnoid hemorrhage at age 34 (treated with clipping surgery). Comorbidities: Hypertension, hyperlipidemia.

Two pregnancies, two children.

Height, 155.0 cm; weight, 60.0 kg [body mass index (BMI), 25.0 kg/m2]; body temperature, 36.4 °C; blood pressure, 154/72 mmHg; pulse, 52 bpm (regular); SpO2, 98% (room air). Speculum examination: No abnormal findings in the cervix or vaginal wall. No abnormal bleeding or discharge. Bimanual examination: A soft, elastic pelvic mass palpable up to three fingerbreadths above the umbilicus, with no tenderness. Cervical cytology: Negative for intraepithelial lesion or mali

White blood cell count, 6000/μL; red blood cell count, 3.71 × 106/μL; hemoglobin, 12.8 g/dL; platelet count, 149 × 10³/μL; total protein, 7.0 g/dL; total bilirubin, 0.8 mg/dL; aspartate aminotransferase, 23 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase,

Tumor markers: Cancer antigen, 125 9.9 U/mL; carcinoembryonic antigen, 2.1 ng/mL; and carbohydrate antigen 19-9, 10.2 U/mL. Cardiopulmonary function assessment: Electrocardiogram demonstrated no ST-T abnormalities. Echocardiography revealed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 67.8% with good wall motion. Chest X-ray exhibited no ab

Ultrasonography findings: A large cystic mass occupying the entire abdominal cavity from the upper abdomen to the pelvis was observed. Pelvic computed tomography findings: A large cystic mass measuring approximately 30 cm occupied the abdominal and pelvic cavities. No apparent cystic clustering, solid components, or irregular septa were observed within the tumor (Figure 1).

Based on these results, we discussed with the anesthesiologists the feasibility of laparoscopy-assisted adnexectomy under general anesthesia and determined that surgery could safely be performed. After providing a thorough explanation to the patient and her family, the following procedure was conducted.

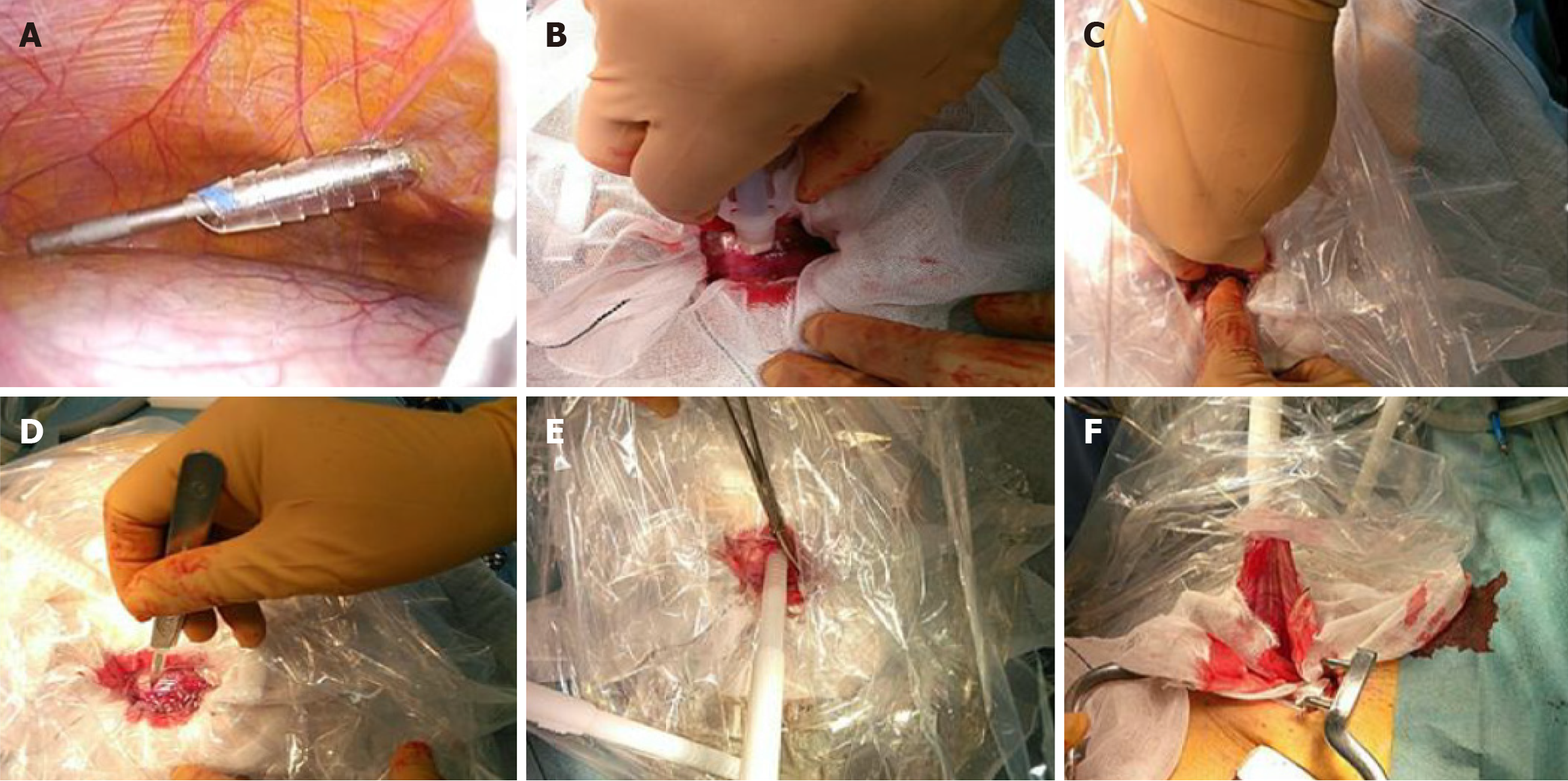

Under general anesthesia, the patient was placed in the lithotomy position, and the surgery was initiated. A 10-mm scope was inserted through the umbilicus to inspect the peritoneal cavity for adhesions or lesions. Ascitic fluid was collected for cytological examination (Figure 2A). The giant ovarian tumor originated from the left ovary. After intra-abdominal inspection, a transverse incision approximately 4 cm in length was made in the lower abdomen. To prevent spillage of Aron alpha (Aron alpha a “Sankyo”®, Daiichi Sankyo Co., Tokyo) onto surrounding tissues and adhesion to other organs, gauze was placed around the tumor (Figure 2B). Aron alpha was applied in a grid pattern to the tumor surface, and a sterilized vinyl bag was pressed manually against the tumor to adhere it firmly (Figure 2C). Once adhesion of Aron alpha to the tumor was confirmed, the vinyl bag was cross-incised from the inside using a scalpel (Figure 2D), and both the tumor and the vinyl bag were clamped with Kocher forceps. The cystic contents were then aspirated from within the bag (Figure 2E), successfully preventing leakage of the tumor fluid into the abdominal cavity. After sufficient aspiration, the ovarian tumor was gently moved outside the body (Figure 2F). The ureteral course was identified, and the infundibulopelvic ligament was ligated and transected, allowing removal of the affected adnexa. The contralateral adnexa were treated in the same manner, with ligation and transection of the infundibulopelvic ligament followed by adnexal excision. After bilateral adnexectomy, the peritoneal cavity was irrigated with saline, and the surgery was completed.

The total operative time was 1 hour and 25 minutes, with minimal blood loss. The postoperative course was un

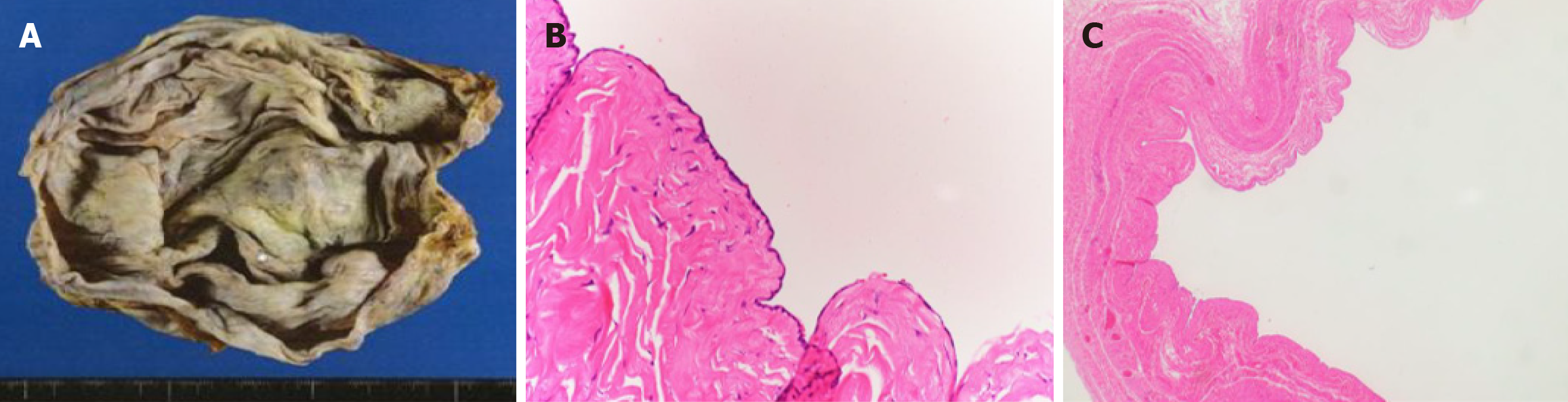

The patient was discharged as scheduled on postoperative day 5. After discharge, there was no decline in ADL or cognitive function. Ascitic cytology was negative, and the pathological diagnosis was serous cystadenoma (Figures 3).

Older adults exhibit lower physiological function and physiologic reserve, and once complications occur, recovery tends to take longer[3]. In preoperative assessment, in addition to evaluating the disease for which surgical treatment is indicated, it is important to consider that older adults often have preexisting comorbidities. Compared with younger individuals, older adults have higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, chronic cardiac disease, chronic obstructive pu

To prevent postoperative complications and perform surgery as safely as possible, various preoperative evaluation methods have been developed to predict postoperative outcomes and overall operative risk. In addition to the E-PASS scoring system used in our case, other methods have been developed in the United States [American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score and the Charlson comorbidity index] and the United Kingdom [physiological and operative severity score for the enUmeration of mortality and morbidity (POSSUM) score][21-23]. The ASA score evaluates smoking and drinking history, BMI, preexisting diseases, and cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events within the previous three months. The Charlson comorbidity index assigns scores based on the presence or absence of comorbidities, including cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, chronic lung disease, diabetes, and collagen disease. Nonetheless, neither of these two systems incorporates age as a factor. The POSSUM score calculates predicted complication and mortality rates based on a physiological score that includes age, preoperative laboratory data, and comorbidities, and an operative severity score that quantifies operative factors. Although age is included in this system, patients aged 71 years and older are grouped together; therefore, it does not distinguish between patients aged 71-80 and those aged 80 years or older. Conversely, the E-PASS used in the present case comprises three components: The PRS, which represents the patient’s physiological status; the SSS, which reflects the magnitude of the surgical procedure; and the CRS, which integrates both. The PRS includes age as a factor, making this method more age-sensitive compared with the systems mentioned above. Furthermore, E-PASS distinguishes between laparoscopic and open procedures, aligning it more closely with current surgical practices. It is a simple scoring system that does not require special equipment and can be calculated from routine preoperative tests and surgical data. Compared with other risk assessment tools, it is easy to implement un

Recently, in surgery, the concept of frailty-a condition where vulnerability to health disturbances rises due to age-related functional decline and reduced physiologic reserve-has garnered increasing attention. Preoperative frailty has been shown to be strongly associated with adverse outcomes such as perioperative mortality and postoperative complications, as well as discharge to facilities other than home[23]. Therefore, including frailty assessment in the preoperative evaluation of older adults is essential. In this case, the patient was frail, presenting with three items on the FRAIL scale: Subjective fatigue, reduced daily activity, and decreased physical function. Accordingly, it was necessary to consider not only postoperative functional recovery but also the prevention of further frailty progression.

Originating in Northern Europe, the concept of ERAS has been proposed as a perioperative management approach to promote postoperative recovery and improve prognosis in surgical patients. Its effectiveness has been reported in cardiovascular and gastrointestinal surgery, and it is now being adopted for a wide range of surgical procedures. By implementing evidence-based perioperative management strategies in an integrated manner, ERAS aims to reduce metabolic stress, provide optimal pain relief, and promote early oral intake and mobilization. These measures help reduce postoperative complications and enhance functional recovery. Studies have shown that ERAS-based management, including minimally invasive surgery to minimize postoperative dysfunction and early mobilization, contributes to shorter postoperative hospital stays and reduced financial burden on patients[13-16].

In the present case, appropriate preoperative evaluation was performed using the E-PASS scoring system and the FRAIL scale. In addition, perioperative management based on ERAS principles, including early postoperative mobi

In the management of giant ovarian tumors, preoperative diagnosis is based on imaging findings and tumor markers, and when necessary, intraoperative cytology or frozen section histopathological examinations are performed. None

When planning surgical treatment for older adults, it is essential to appropriately evaluate systemic conditions and postoperative complication risk using tools such as the E-PASS scoring system and FRAIL scale, and to manage the perioperative period using the ERAS approach. The Aron alpha method enables minimally invasive removal of giant ovarian tumors without intraperitoneal spillage of cyst contents, and is considered a useful surgical option for older adults with giant ovarian tumors in which malignancy cannot be ruled out.

| 1. | Meyerhardt JA, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Saltz LB, Mayer RJ, Nelson H, Whittom R, Hantel A, Thomas J, Fuchs CS; Cancer and Leukemia Group B 89803. Impact of body mass index and weight change after treatment on cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: findings from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4109-4115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Yang HS, Yoon C, Myung SK, Park SM. Effect of obesity on survival of women with epithelial ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:1525-1532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hamel MB, Henderson WG, Khuri SF, Daley J. Surgical outcomes for patients aged 80 and older: morbidity and mortality from major noncardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:424-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 445] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Evers BM, Townsend CM Jr, Thompson JC. Organ physiology of aging. Surg Clin North Am. 1994;74:23-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dunlop WE, Rosenblood L, Lawrason L, Birdsall L, Rusnak CH. Effects of age and severity of illness on outcome and length of stay in geriatric surgical patients. Am J Surg. 1993;165:577-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bettelli G. Preoperative evaluation in geriatric surgery: comorbidity, functional status and pharmacological history. Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77:637-646. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Haga Y, Ikei S, Ogawa M. Estimation of Physiologic Ability and Surgical Stress (E-PASS) as a new prediction scoring system for postoperative morbidity and mortality following elective gastrointestinal surgery. Surg Today. 1999;29:219-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Haga Y, Ikei S, Wada Y, Takeuchi H, Sameshima H, Kimura O, Furuya T. Evaluation of an Estimation of Physiologic Ability and Surgical Stress (E-PASS) scoring system to predict postoperative risk: a multicenter prospective study. Surg Today. 2001;31:569-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kitano Y, Iwatsuki M, Kurashige J, Kuroda D, Kosumi K, Baba Y, Sakamoto Y, Miyamoto Y, Yoshida N, Haga Y, Baba H. Estimation of Physiologic Ability and Surgical Stress (E-PASS) versus modified E-PASS for prediction of postoperative complications in elderly patients who undergo gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2017;22:80-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Haga Y, Wada Y, Takeuchi H, Kimura O, Furuya T, Sameshima H, Ishikawa M. Estimation of physiologic ability and surgical stress (E-PASS) for a surgical audit in elective digestive surgery. Surgery. 2004;135:586-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schipa C, Luca E, Ripa M, Sollazzi L, Aceto P. Preoperative evaluation of the elderly patient. Saudi J Anaesth. 2023;17:482-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gong S, Qian D, Riazi S, Chung F, Englesakis M, Li Q, Huszti E, Wong J. Association Between the FRAIL Scale and Postoperative Complications in Older Surgical Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Anesth Analg. 2023;136:251-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cavallaro P, Bordeianou L. Implementation of an ERAS Pathway in Colorectal Surgery. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32:102-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Brown ML, Simpson V, Clark AB, Matossian MD, Holman SL, Jernigan AM, Scheib SA, Shank J, Key A, Chapple AG, Kelly E, Nair N. ERAS implementation in an urban patient population undergoing gynecologic surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;85:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pate NP, Thiele RH. Gynecologic ERAS Preoperative Interventions. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2025;68:479-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Whiteside JL, Keup HL. Laparoscopic management of the ovarian mass: a practical approach. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52:327-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Poncelet C, Fauvet R, Boccara J, Daraï E. Recurrence after cystectomy for borderline ovarian tumors: results of a French multicenter study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:565-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kakinuma T, Kakinuma K, Shinohara T, Shimizu A, Okamoto R, Kaneko A, Takeshima N, Yanagida K, Ohwada M. Efficacy and safety of an Aron Alpha method in managing giant ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2023;46:101167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Oresanya LB, Lyons WL, Finlayson E. Preoperative assessment of the older patient: a narrative review. JAMA. 2014;311:2110-2120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dripps RD, Lamont A, Eckenhoff JE. The role of anesthesia in surgical mortality. JAMA. 1961;178:261-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 734] [Cited by in RCA: 732] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32099] [Cited by in RCA: 39719] [Article Influence: 1018.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Copeland GP, Jones D, Walters M. POSSUM: a scoring system for surgical audit. Br J Surg. 1991;78:355-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1126] [Cited by in RCA: 1162] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kim SW, Han HS, Jung HW, Kim KI, Hwang DW, Kang SB, Kim CH. Multidimensional frailty score for the prediction of postoperative mortality risk. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:633-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/