Published online Feb 6, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i4.116648

Revised: January 2, 2026

Accepted: January 19, 2026

Published online: February 6, 2026

Processing time: 80 Days and 14.6 Hours

Ectopic varices present diagnostic and management challenges when encountered unexpectedly in clinical practice. Given their potential for fatal outcomes, with mortality rates reaching 40%, it is essential to discuss their clinical manifestations as well as current management guidelines.

We report the case of a 56-year-old male patient with a history of liver transp

A systematic approach is essential for diagnosing and managing ectopic varices. Further, evidence-based studies are needed to improve outcomes.

Core Tip: Ectopic varices occur at uncommon sites outside the typical locations of esophageal or gastric varices, making their assessment and management particularly challenging. We report the case of a 56-year-old male with a history of liver transplantation and segmentectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma with underlying liver cirrhosis and hepatitis B virus infection. Successful hemostasis was achieved through a combination of embolization and surgical portal vein and superior mesenteric vein bypass.

- Citation: Lee H, Han YH, Chung JW, Kim KO, Kwon KA, Kim JH. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding with duodenal varix: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(4): 116648

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i4/116648.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i4.116648

Ectopic varices occur at uncommon sites outside the typical locations of esophageal or gastric varices, making their assessment and management particularly challenging. Portal hypertension leads to the formation of portosystemic collaterals and varices in unusual locations beyond the gastroesophageal region. Ectopic varices account for 1%-5% of all variceal bleeding and are associated with severe gastrointestinal hemorrhage and high mortality rates[1,2]. Unexpected varices may occur in various sites, most commonly in the duodenum, which represents 17%-40% of all ectopic cases[3]. Other possible sites include the jejunum, ileum, colon, parastomal regions, biliary tract, genitourinary organs such as the urinary bladder and vagina, and the retroperitoneum, where they are occasionally encountered in clinical practice[3].

Ectopic varices develop secondary to portal hypertension, most often caused by cirrhosis, extrahepatic portal vein obstruction, Budd-Chiari syndrome, portal vein thrombosis, or post-surgical shunts. These ectopic collaterals form connections between portal tributaries and systemic veins and are classified according to their location, based on the feeding and draining veins involved. Specifically, duodenal varices receive blood from the superior or inferior pancreaticoduodenal veins and drain into the gonadal, inferior vena cava, or capsular veins[1,4,5]. Jejunal and ileal varices are supplied by branches of the superior mesenteric vein and drain into retroperitoneal veins[1,6]. Colonic varices are fed by the superior or inferior mesenteric veins and drain into the iliac veins[1,7].

Clinically, ectopic varices often present with massive or intermittent bleeding, manifesting as melena, hematochezia, or hematemesis. The mortality rate associated with bleeding from ectopic varices is approximately 40% and the rebleeding rate ranges from 20%-40% unless portal hypertension is adequately controlled[1].

A 56-year-old male visited the gastroenterology outpatient clinic with complaints of melena, requesting further ev

Approximately one month prior to this visit, the patient had been discharged following recovery from upper gastro

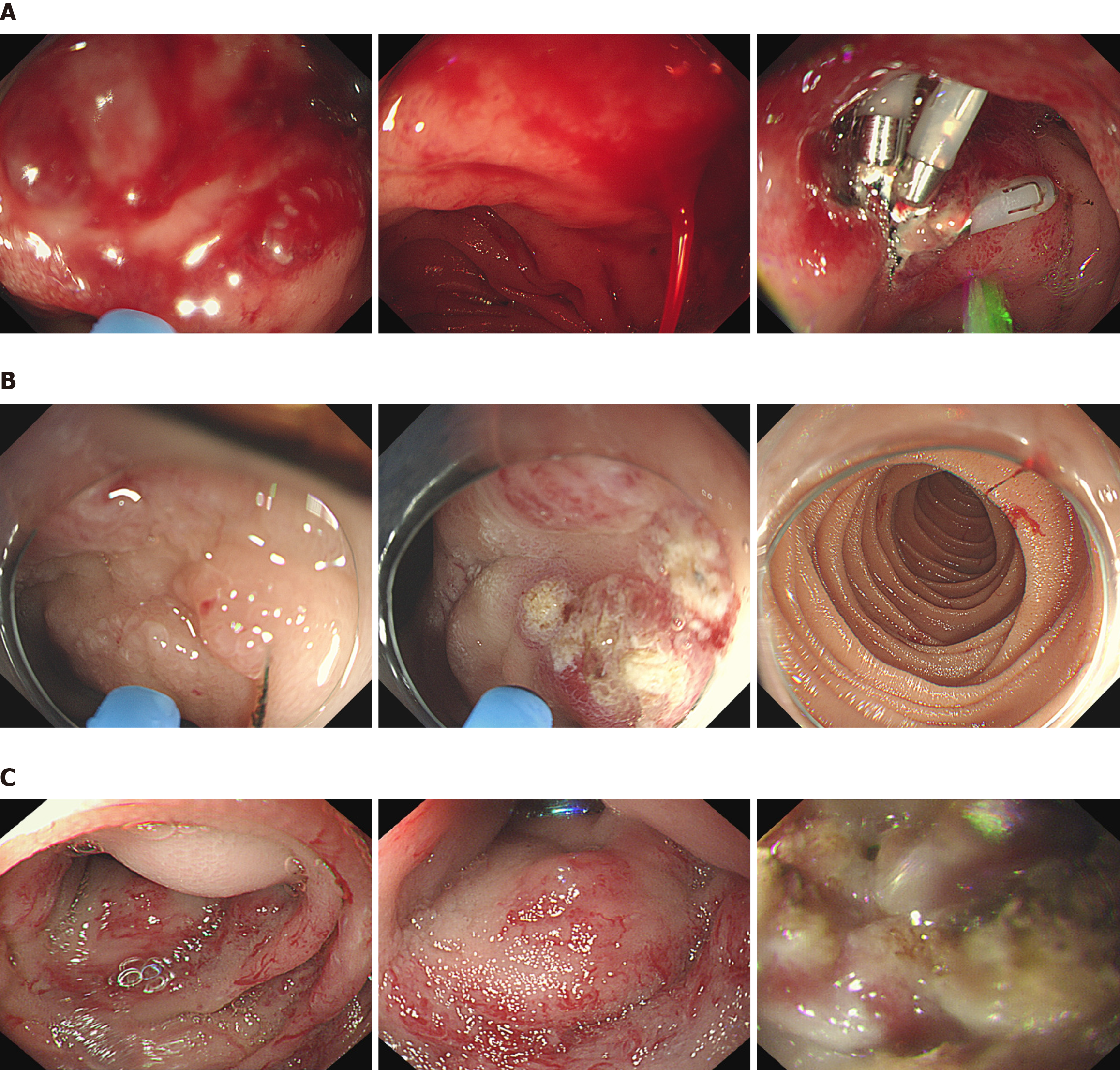

The 56-year-old male had a past medical history of liver transplantation and segmentectomy with cholecystectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma on a background of liver cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis B virus infection, performed in 2016. He had also undergone gastrojejunostomy for a perforated duodenal ulcer in 2009. Since after cholecystectomy in 2016, he had recurrently undergone multiple common bile duct stone removal by percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy with percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) owing to post-surgical anastomotic stricture and deformity causing limited conventional endoscopic approach with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). During his admission one month prior to the current visit, initial esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed a large amount of blood clots in the gastric lumen, suggesting active bleeding. An active ulcer at the anastomosis site with visible vessel exposure (Forrest IIb) was identified and treated with argon plasma coagulation (APC) followed by clipping to achieve hemostasis (Figure 1A).

The patient had no relevant family history.

The patient presented with hemodynamic and respiratory stability. Physical examination revealed a PTBD tube in place, without abdominal tenderness. On the day of his presentation to the emergency department, the patient appeared pale and lethargic. His vital signs, including body temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation, were within normal limits. Physical examination revealed no abnormalities in the abdominal, cardiovascular, pulmonary, or skin systems, except for anemic conjunctiva.

Initial laboratory results showed (Table 1): White blood cell (WBC) count 4.9 × 109/L, hemoglobin (Hb) 6.1 g/dL, and platelet count 275 × 109/L. Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine were 19 U/L, 0.39 mg/dL, 23.6 mg/dL, and 0.96 mg/dL, respectively. Coagulation profile had prothrombin time 12.1 seconds with international normalized ratio (INR) 1.1. Consequent laboratory findings after recurrent bleeding just before evaluation with enteroscope presented on hospital day 20 (Table 1): WBC count 4.3 × 109/L, Hb 7.6 g/dL, and platelet count 243 × 109/L. Serum AST, total bilirubin, BUN, and creatinine were 22 U/L, 0.51 mg/dL, 10.4 mg/dL, and 0.74 mg/dL. Coagulation profile demonstrated prothrombin time 12.6 seconds and INR 1.2.

| Parameter | Reference range | Initial presentation (hospital day 1) | Recurrent bleeding (hospital day 20) |

| Complete blood count | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.0-17.0 | 6.1 | 7.6 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 39-52 | 20.6 | 22.8 |

| White blood cells (× 109/L) | 4.0-10.0 | 4.9 | 4.3 |

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 150-400 | 275 | 243 |

| Renal function | |||

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 8-23 | 23.6 | 10.4 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.6-1.2 | 0.96 | 0.74 |

| Estimated GFR (mL/minute/1.73 m2) | > 60 | 93 | 106 |

| Electrolytes | |||

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 135-145 | 138 | 140 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.5-5.1 | 4.4 | 4.0 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 98-107 | 105 | 107 |

| Liver function tests | |||

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 0-40 | 19 | 22 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 0-40 | 11 | 25 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 40-129 | 117 | 118 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.2-1.2 | 0.39 | 0.51 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.5-5.0 | 3.6 | 2.9 |

| Coagulation profile | |||

| Prothrombin time (second) | 11-14 | 12.1 | 12.6 |

| INR | 0.8-1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

Initial EGD after admission revealed a healing anastomotic ulcer without evidence of active bleeding. However, several hyperemic spots suggestive of angiodysplastic changes were observed near the anastomosis site, and APC was per

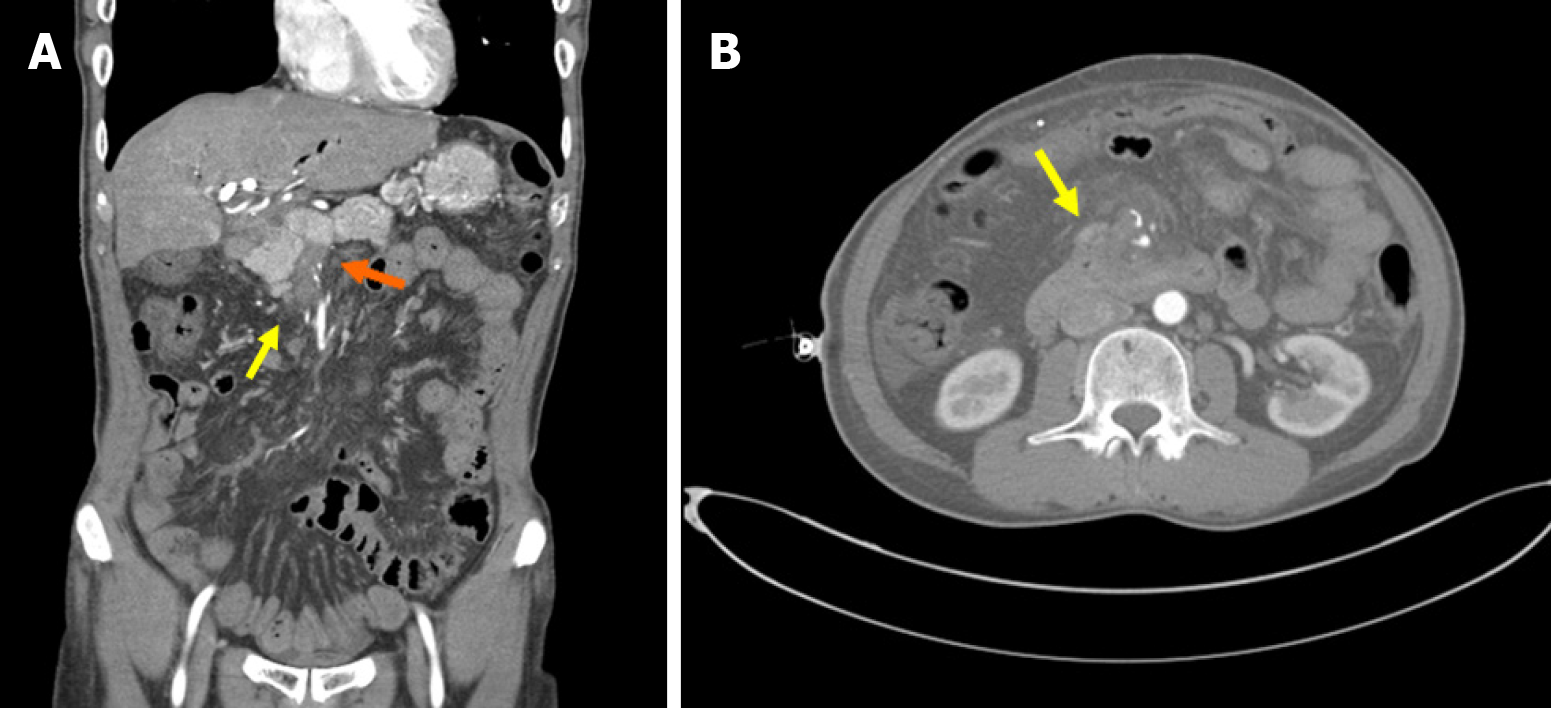

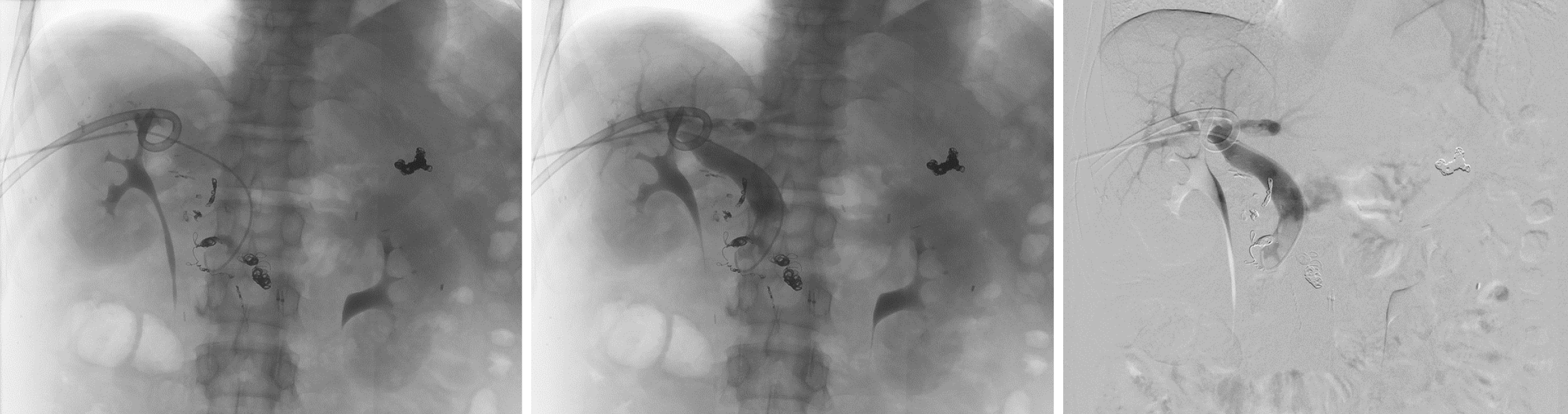

During the second angiography, the SMV venogram demonstrated distal SMV occlusion and the presence of a duodenal varix.

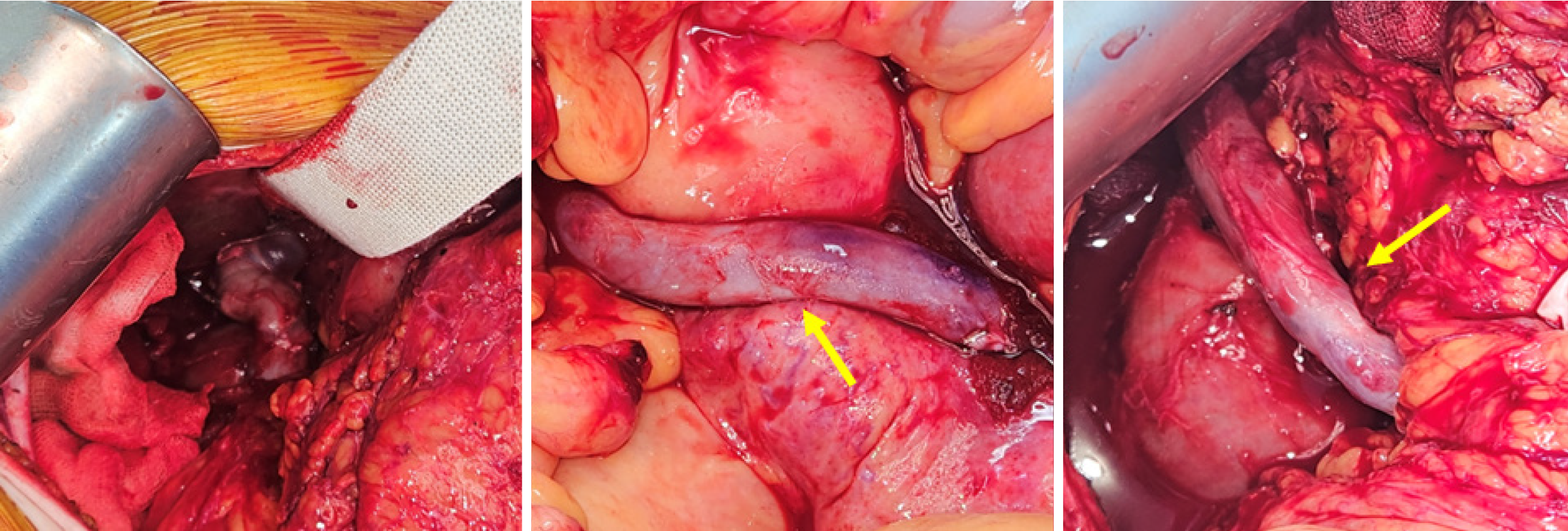

Due to the location of the inflow vein above the SMV occlusion, vascular access was limited. Therefore, superselective catheterization was achieved using a microcatheter, followed by embolization with 33% glue and four microcoils at the draining vein of the duodenal varix, resulting in successful hemostasis (Figure 3). After embolization, terlipressin was administered for pharmacological management, and scheduled surgical intervention with PV-SMV bypass was per

After PV-SMV bypass surgery and discharge, the patient clinically presented no signs of recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding. Postoperative endoscopic and radiologic evaluations were performed to assess the duodenal varix, which had been the primary cause of his clinical presentation. Follow-up CT imaging demonstrated improvement of the duodenal varix. Endoscopic examination performed three months after surgery and discharge showed normal findings at the anastomosis site, with no evidence of recurrent bleeding from either the afferent or efferent loop.

The ectopic location of varices is the most significant factor complicating their assessment and management, particularly when they present in unexpected sites. This case illustrates the diagnostic challenges posed by ectopic varices, which manifested as acute, severe, intermittent bleeding despite negative findings on upper endoscopic evaluation. Therefore, a diagnostic approach based on a comprehensive assessment of vascular integrity, rather than focusing solely on localized findings, is essential, especially in patients with comorbidities related to portal hypertension.

Ectopic varices are most commonly found in the duodenum but can also occur in the small bowel (jejunum and ileum), colon, parastomal sites, biliary tract, and genitourinary system[3]. Norton et al[2] reported that duodenal varices were the most common type (17%) among 169 patients with ectopic variceal bleeding, followed by varices in the jejunum and ileum (17%), colon (14%), and rectum (8%). However, data from a national survey in Japan showed differing results, with rectal varices being the most common (44.5%), followed by duodenal varices (32.9%)[8].

From a pathophysiological perspective, ectopic varices develop as a secondary consequence of portal hypertension caused by cirrhosis, extrahepatic portal vein obstruction, Budd-Chiari syndrome, portal vein thrombosis, or post-surgical shunts.

Clinically, they may present with massive or intermittent bleeding, manifesting as melena, hematochezia, or he

Current therapeutic guidelines recommend individualized management strategies based on the location, bleeding activity, anatomy, and portal pressure of the ectopic varices[9]. Endoscopic therapies, including band ligation, cyanoacrylate injection, endoscopic clipping, or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided coil and glue injection, are currently available options[10-12]. For duodenal varices, EUS-guided coil and glue injection may be considered[11], while rectal varices can be treated with band ligation or sclerotherapy[13]. However, these procedures carry risks of perforation, glue embolism, and recurrence due to persistent collateral circulation.

Independency from radiation exposure as well as minimal invasiveness promotes wide spread introduction of EUS guided therapy. Since the case patient has undergone hemodynamic instability with progression of active bleeding, application of EUS guided therapy was out of consideration. Real-time manipulation with high contrast resolution enables various treatment approach in therapeutic endoscopic field including variceal therapy. EUS guided vascular therapy allows real-time visualization of variceal structure to perform minimally invasive targeted treatment with effective injection of sclerotic agents[14]. International multi-center study with propensity-matched analysis demon

Interventional radiologic procedures including balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration, plug-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration (PARTO), balloon-occluded antegrade transvenous obliteration, transhepatic embolization using microcoils and sclerosants, and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, offer additional therapeutic options (Table 2)[5,19-22].

| Ref. | Varix site | Modality | Intervention | Outcome |

| Kim et al[22], 2020 | Duodenum | Interventional radiology | Percutaneous trans-splenic variceal obliteration | Alternative option for balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration |

| Lee et al[5], 2023 | Duodenum | Interventional radiology | PARTO | Successful PARTO for an isolated duodenal varix |

| Hau et al[24], 2014 | Duodenum | Surgery | Collateral caval shunt | Surgical shunt controlled bleeding in non-cirrhotic portal hypertension |

| Solanki et al[23], 2021 | Jejunum | Surgery | Segmental bowel resection | Effective hemostasis on localized, refractory ectopic varices |

Surgical management, including segmental resection or shunt creation, is generally reserved for localized or refractory ectopic varices (Table 2)[23,24].

Pharmacological management includes the use of nonselective β-blockers such as propranolol and carvedilol to lower portal pressure, as well as octreotide or terlipressin to reduce splanchnic blood flow and variceal pressure[9,25].

Recent case reports have described both endoscopic and radiologic interventions for duodenal varices. Hamilton et al[26] successfully performed endoscopic band ligation, while Lee et al[5] reported a case treated with PARTO without complications.

Therefore, it is noteworthy that our case represents a remarkable outcome achieved through a combined interventional radiology and surgical approach for the management of duodenal ectopic variceal bleeding.

In conclusion, a comprehensive and systematic approach is essential for both the diagnosis and therapeutic decision-making in cases of ectopic varices. Given their potential for obscurity and high mortality, further evidence-based clinical studies are needed to guide optimal assessment and management strategies.

| 1. | Saad WE, Lippert A, Saad NE, Caldwell S. Ectopic varices: anatomical classification, hemodynamic classification, and hemodynamic-based management. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;16:158-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Norton ID, Andrews JC, Kamath PS. Management of ectopic varices. Hepatology. 1998;28:1154-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Patel A, Fischman AM, Saad WE. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration of gastric varices. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:721-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Copelan A, Chehab M, Dixit P, Cappell MS. Safety and efficacy of angiographic occlusion of duodenal varices as an alternative to TIPS: review of 32 cases. Ann Hepatol. 2015;14:369-379. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Lee KK, Park JY, Choi WS, Cho YY. Plug-Assisted Retrograde Transvenous Obliteration for the Treatment of Duodenal Variceal Bleeding - A Case Report and Literature Review. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2023;82:295-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | You Y, Wang W, Zhong J, Chen S. BRTO for ectopic small intestinal varices bleeding via dilated superior mesenteric veins and left ovarian vein: A case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2025;20:1058-1063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liu C, Srinivasan S, Babu SB, Chung R. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration of colonic varices: a case report. CVIR Endovasc. 2020;3:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Watanabe N, Toyonaga A, Kojima S, Takashimizu S, Oho K, Kokubu S, Nakamura K, Hasumi A, Murashima N, Tajiri T. Current status of ectopic varices in Japan: Results of a survey by the Japan Society for Portal Hypertension. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:763-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tranah TH, Nayagam JS, Gregory S, Hughes S, Patch D, Tripathi D, Shawcross DL, Joshi D. Diagnosis and management of ectopic varices in portal hypertension. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:1046-1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dharmadhikari S, Everwine M, Joo L. S3330 A Rare Case of an Isolated Duodenal Varix Treated Endoscopically With Endo Clips. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:S2206-S2206. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Bahdi F, George R, Patel K. EUS-guided coiling and cyanoacrylate injection of ectopic duodenal varices. VideoGIE. 2021;6:35-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sharma B, Mitchell R, Parapini M, Donnellan F. Cyanoacrylate injection of an ectopic variceal bleed at a choledochojejunal anastomotic site in a patient with post-Whipple anatomy. VideoGIE. 2020;5:29-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Al Khalloufi K, Laiyemo AO. Management of rectal varices in portal hypertension. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:2992-2998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 14. | Dhar J, Samanta J. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided vascular interventions: An expanding paradigm. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;15:216-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Samanta J, Nabi Z, Facciorusso A, Dhar J, Akbar W, Das A, Birda CL, Mangiavillano B, Auriemma F, Crino SF, Kochhar R, Lakhtakia S, Reddy DN. EUS-guided coil and glue injection versus endoscopic glue injection for gastric varices: International multicentre propensity-matched analysis. Liver Int. 2023;43:1783-1792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Robles-Medranda C, Nebel JA, Puga-Tejada M, Oleas R, Baquerizo-Burgos J, Ospina-Arboleda J, Valero M, Pitanga-Lukashok H. Cost-effectiveness of endoscopic ultrasound-guided coils plus cyanoacrylate injection compared to endoscopic cyanoacrylate injection in the management of gastric varices. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;13:13-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dhar J, Gorsi U, Sinha SK, Samanta J. Expanding Horizons of Vascular Interventions: Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Angioembolization for a Refractory Upper Gastrointestinal Bleed From a Gastric Dieulafoy Lesion. ACG Case Rep J. 2025;12:e01816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dhar J, Bharath NP, Mahajan G, Bhujade H, Gupta P, Facciorusso A, Samanta J. Bleeding parastomal varices in a case of decompensated cirrhosis with tubercular abdominal cocoon: endoscopic ultrasound-guided angioembolization with coil and glue to the rescue. Endoscopy. 2024;56:E439-E440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kim HC, Miyayama S, Lee EW, Lim DY, Chung JW, Jae HJ, Choi JW. Interventional Radiology for Bleeding Ectopic Varices: Individualized Approach Based on Vascular Anatomy. Radiographics. 2024;44:e230140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dervishi M, Stevens A, Sutter C, Chiong I, Davidson J. Endovascular Management of Bleeding Ectopic Varices. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2025;28:101080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Waguri N, Osaki A, Watanabe Y. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for treatment of gastric varices. World J Hepatol. 2021;13:650-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 22. | Kim HW, Yoon JS, Yu SJ, Kim TH, Seol JH, Kim D, Jung JY, Jeong PH, Kwon H, Lee HS, Lee SH, Choi JS, Park SJ, Jee SR, Lee YJ, Seol SY. Percutaneous Trans-splenic Obliteration for Duodenal Variceal bleeding: A Case Report. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2020;76:331-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Solanki S, Jena SS, Das SAP, Yadav A, Mehta NN, Nundy S. Isolated ectopic jejunal varices in a patient with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction - A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2021;86:106299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hau HM, Fellmer P, Schoenberg MB, Schmelzle M, Morgul MH, Krenzien F, Wiltberger G, Hoffmeister A, Jonas S. The collateral caval shunt as an alternative to classical shunt procedures in patients with recurrent duodenal varices and extrahepatic portal vein thrombosis. Eur J Med Res. 2014;19:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Elfeki MA, Singal AK, Kamath PS. Pharmacotherapies for Portal Hypertension: Current Status and Expanding Indications. Curr Hepatol Rep. 2023;22:44-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hamilton LE, Carroll J, Tran P. A case report of successful band ligation of bleeding anastomotic duodenal varix in an adolescent patient. JPGN Rep. 2025;6:206-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/