Published online Jan 26, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i3.116125

Revised: December 13, 2025

Accepted: January 6, 2026

Published online: January 26, 2026

Processing time: 80 Days and 15 Hours

Histiocytic sarcoma (HS) is a rare lymphohematopoietic malignancy with non

A 67-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital because of a large splenic mass that was detected during a routine health examination 1 month before pre

Given the paucity of cases and the poor prognosis of splenic HS, whose definitive diagnosis hinges exclusively on pathology, and given that all current therapeutic strategies are based on isolated case reports, it is imperative to enhance our understanding of this disease to improve patient diagnosis and management.

Core Tip: Splenic histiocytic sarcoma (HS) is a rare lymphohematopoietic malignancy with nonspecific clinical manifestations, diagnostic challenges, high aggressiveness, and a poor prognosis. A 67-year-old woman was found to have a large splenic mass during a routine physical examination 1 month before presentation. After multidisciplinary discussion, laparoscopic splenectomy was recommended. The pathological findings were most compatible with the diagnosis of HS. A 6-month postoperative telephonic follow-up revealed that the patient felt well. Despite the poor prognosis, HS remains treatable. Early and definitive diagnosis based on pathology is required to optimize treatment.

- Citation: Jia ZD, Zhang CY, Liang SZ, Li HL. Primary splenic histiocytic sarcoma: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(3): 116125

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i3/116125.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i3.116125

Histiocytic sarcoma (HS) is a rare and aggressive lymphohematopoietic malignancy with broad age of onset, nonspecific clinical presentation, diagnostic challenges, and a poor prognosis[1]. Primary involvement of the spleen is exceedingly uncommon, with only sporadic cases reported in the literature[2]. Here, we present the clinical course of a patient with splenic HS.

A 67-year-old woman was found to have a large splenic mass during a routine physical examination 1 month before presentation.

The patient was admitted to our hospital on March 9, 2025. She reported only occasional discomfort in the left lumbar region and denied other symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, chills, or fever.

During hospitalization at another hospital in February 2025, the patient was diagnosed with bradycardia and underwent pacemaker implantation. After discharge, her medication regimen included regular oral trimetazidine hydrochloride (20 mg, three times daily) and sotalol hydrochloride (80 mg, twice daily).

The patient had no relevant personal or family history.

The findings of the physical examination were unremarkable.

Laboratory investigations revealed a hemoglobin level of 97.00 g/L, white blood cell count of 10.85 × 109/L, and platelet count of 330 × 109/L. The level of B-type natriuretic peptide was 351 pg/mL. The patient tested positive for hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B e antibody, and hepatitis B core antibody, with a hepatitis B virus DNA load of 4.06 × 102 IU/mL. The level of the tumor marker cancer antigen-125 was elevated to 220.6 U/mL. All other parameters, including rheumatological, immunological, tuberculosis, and thyroid function test results, were within normal limits.

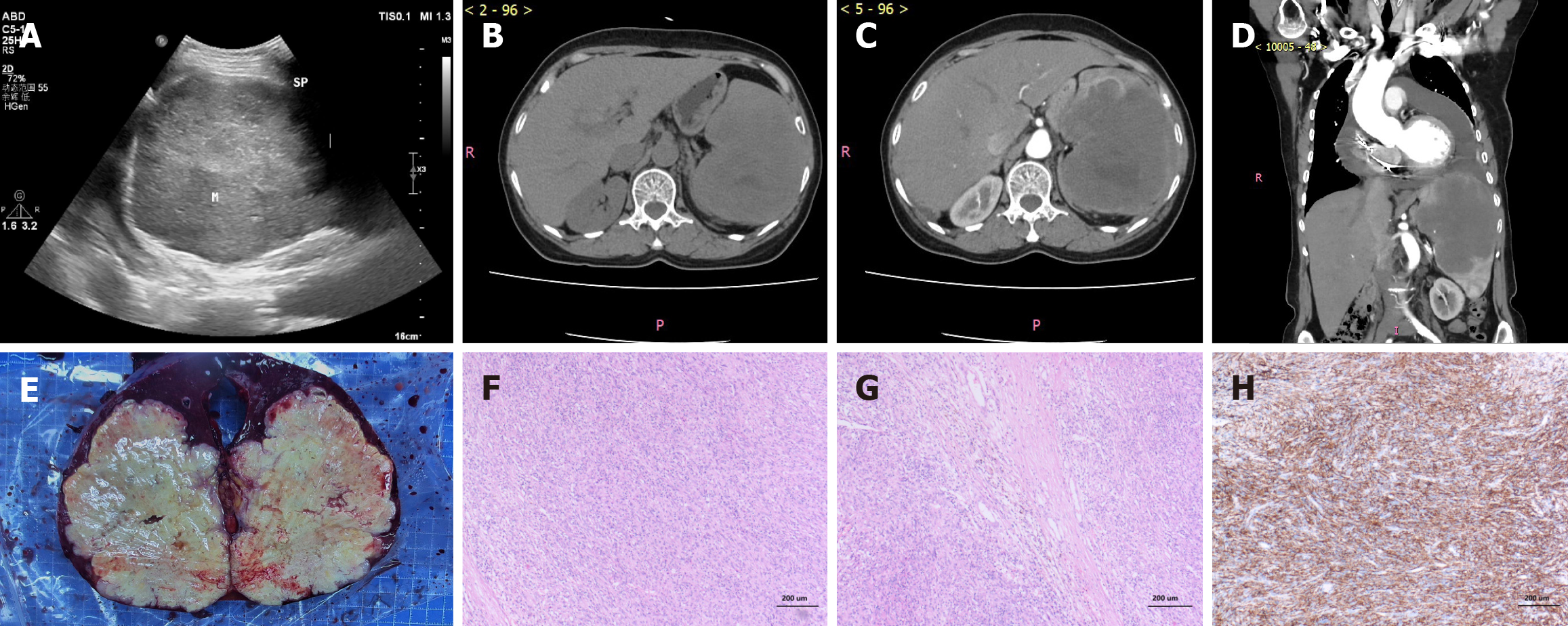

Color Doppler ultrasonography of the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, and spleen (Figure 1A) revealed a cyst in segment 7 of the right hepatic lobe and a large splenic mass (approximately 11.2 cm × 13.6 cm) occupying nearly the whole spleen, the nature of which was undetermined. The spleen was significantly enlarged. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the upper abdomen (Figure 1B-D) revealed a large occupying lesion measuring about 8.8 cm × 11.6 cm × 11.8 cm in the spleen, suggesting a possible lymphangioma, along with an accessory spleen and cysts in segment 2 and segment 8 of the liver. The spleen was significantly enlarged. CT also showed the post-pacemaker implantation status, cardiomegaly, and a moderate amount of pericardial effusion. Cardiac ultrasonography confirmed moderate pericardial effusion, pacemaker implantation, impaired left ventricular diastolic function, and a slightly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction of 52%. Electrocardiogram findings included: (1) Sinus tachycardia; (2) Ventricular paced rhythm; (3) Occasional premature ventricular contractions; (4) First-degree atrioventricular block; (5) Left axis deviation; (6) ST-T segment changes; (7) Prolonged Q-T interval; and (8) Recommendation for pacemaker interrogation.

Following consultation with the Department of Cardiology, priority was given to addressing the splenic lesions. After multidisciplinary discussion, laparoscopic splenectomy was recommended.

Biopsy and pathological examination revealed the results (Figure 1E-H).

The specimen consisted of one spleen measuring 14 cm × 12 cm × 7 cm, displaying a grayish-white and grayish-red cut surface. A well-defined, grayish-yellow tumor measuring 12 cm × 10 cm × 9 cm was identified within the parenchyma. The tumor was solid with a firm consistency. Extensive areas of necrosis were evident.

The tumor cells were spindle-shaped to epithelioid, exhibiting significant atypia, abundant cytoplasm, prominent nucleoli, and noticeable mitotic figures. The stroma showed extensive hemorrhage, necrosis, and inflammatory cell infiltration.

Positive for CD68 (diffuse+), CD163 (diffuse+), CD4 (+), lysozyme (focal+), lactoferrin antibody (focal+), CD43 (focal+), CD3 (focal+), CD79a (small foci+), epidermal growth factor receptor (focal+); negative for CD1a, D2-40, S-100, anaplastic lymphoma kinase, desmin, CD21, CD35, PD-1, CD23, IgG, IgG4, CD30, v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B, langerin; internal controls were CD8 (highlighted T cells), ETS-related gene (highlighted vasculature), smooth muscle actin (highlighted vasculature), and CD34 (highlighted vasculature).

The Ki-67 index was approximately 30%.

Both Grocott’s methenamine silver and periodic acid-Schiff staining yielded negative results.

Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNAs were detected.

The combined morphological features, immunohistochemical profile, specific staining results, and Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNA positivity were consistent with those of malignant lymphohematopoietic neoplasms. These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of splenic HS.

On March 12, 2025 the patient underwent laparoscopic splenectomy under general anesthesia. Intraoperatively, the spleen was significantly enlarged, largely replaced by a tumor measuring approximately 12 cm × 10 cm × 9 cm, and adhered to the surrounding tissues, particularly at the posterior diaphragmatic surface. The patient recovered well after surgery. An oncology consultation recommended initiating chemotherapy 3 weeks after surgery. However, the patient and her family opted for discharge to recuperate before deciding on further treatment.

The patient recovered well and was successfully discharged. A 6-month postoperative telephonic follow-up revealed that she felt well and declined further therapy, preferring to seek reevaluation only if the symptoms progressed.

HS, previously termed “malignant histiocytic lymphoma”, “histiocytic medullary reticulosis”, or “malignant histiocytosis”, is a rare, localized tumor. With advancements in immunohistochemistry and molecular biology, it has been recognized that many cases previously diagnosed as HS were actually non-Hodgkin lymphomas of B-cell or T-cell origin or lymphoma-associated hemophagocytosis. The term HS was first introduced by Mathé et al[1]. HS typically involves the skin, lymph nodes, and intestinal tract; however, some patients may later develop disseminated disease with systemic manifestations and multi-organ involvement, a condition sometimes still referred to as malignant histiocytosis. The 2001 World Health Organization classification categorizes HS as a neoplasm of macrophage/histiocyte origin and defines it as a rare lymphohematopoietic tumor. HS has a broad age of onset, affecting infants, children, and adults, with most cases occurring among adults (median age: 46 years; male-to-female ratio: 2:1). The most common symptoms include fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Primary HS of the spleen is extremely rare, with few cases reported in the literature. In contrast, secondary involvement of the spleen, particularly during the terminal stages of the disease, is relatively common[2].

The clinical presentation of splenic HS is often asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic for prolonged periods. Several patients present with splenomegaly and thrombocytopenia. Splenic enlargement is typically insidious and can remain undetected. Reports indicate that thrombocytopenia can be an early sign and sometimes the sole clinical manifestation[3,4]. Other laboratory abnormalities, including anemia and/or lymphocytopenia, vary among patients and at different disease stages[3,4]. In splenic HS, worsening liver function in the absence of other symptoms may be indicative of hepatic infiltration[2]. In this case, the patient was largely asymptomatic, with splenomegaly as the primary finding.

The current diagnosis of HS primarily relies on clinical presentation, cytomorphology, immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, and molecular genetic features. The diagnostic criteria are as follows: (1) Morphology: Microscopic exa

The differential diagnosis of HS includes the following: (1) Anaplastic large cell lymphoma and metastatic carcinoma: Anaplastic large cell lymphoma is positive for CD30 and epithelial membrane antigen. Metastatic carcinoma is positive for epithelial markers (e.g., epithelial membrane antigen and cytokeratin). In contrast, HS is negative for both CD30 and epithelial markers; (2) Malignant melanoma: Melanoma cells are diffusely distributed with eosinophilic cytoplasm, prominent nucleoli, and frequent mitoses, exhibiting both epithelial and sarcomatous differentiation. It is positive for human melanoma black 45 and S-100, which helps distinguish it from HS; (3) Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Langerhans cell histiocytosis lacks significant nuclear atypia and is characterized by the presence of eosinophils and a lymphoid background. The tumor cells are positive for CD1a and S-100, and Birbeck granules are visible on electron microscopy. Conversely, HS is negative for CD1a; (4) Acute monocytic leukemia: This is a malignancy of monoblastic cells, primarily involving the bone marrow and peripheral blood, and it often presents as anemia and thrombocytopenia. Serum ly

Molecular evaluation using next-generation sequencing has become increasingly important for diagnosing and understanding HS. Identifying characteristic genetic mutations aids in confirming the neoplasm’s clonal origin and may uncover actionable therapeutic targets. Research has underscored the significant pathogenic role of mitogen-activated protein kinases pathway activation in HS. Furthermore, tumorigenesis is driven by recurrent copy number losses involving cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A and mutations in suppressor genes like tumor protein 53 and SET domain containing 2. HS reveals a typically intricate genomic landscape, correlating with its high-grade cytomorphology and clinically aggressive behavior[10].

HS is characterized by high malignancy, strong invasiveness, and a poor prognosis, with most patients succumbing to the disease within 2 years of diagnosis[11]. Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the reported cases of splenic HS. The prognosis is influenced by multiple factors, including tumor location, size, and stage, and no effective treatment regimen has been established. Surgical resection is the most reliable approach for treating localized diseases. Po

| No. | Age | Sex | Spleen size (cm) | Metastasis | Treatment | Survival | Ref. |

| 1 | 38 | M | NA | NA | S | NA | Franchino et al[21] |

| 2 | 29 | M | 17 × 13 × 8 | Liver | S | 5 years 1 month | Kimura et al[3] |

| 3 | 60 | M | 8 × 8 × 8 | Liver, BM | S + C | 1-year 6 months | Kimura et al[3] |

| 4 | 66 | F | 1 × 1 × 3 | Liver, BM | R + S + C | 2 years 6 months | Kimura et al[3] |

| 5 | 71 | F | 14 × 12 × 10 | Lymph node | C | 6 months | Audouin et al[4] |

| 6 | 58 | F | 15 × 9 × 10 | Liver | R + S + C | 3 months | Oka et al[5] |

| 7 | 82 | F | NA | Liver | R | 1 month | Kobayashi et al[22] |

| 8 | 67 | F | 14 × 12 × 8 | BM | S | 6 months | Yamada et al[23] |

| 9 | 69 | M | NA | Liver | C + S | 3 years 5 months + | Yamamoto et al[24] |

| 10 | 81 | F | 21 × 12 × 5 | Liver | S | 5 months | Yamamoto et al[25] |

| 11 | 40 | F | 12 × 8 × 4 | BM | S | 5 months + | Huang et al[26] |

| 12 | 61 | M | 19 × 13 × 9 | None | C + S | 6 months + | Kobayashi et al[27] |

| 13 | 69 | F | 28 × 18 × 10 | None | S | 5 months | Zhang et al[2] |

| 14 | 46 | F | 15 × 11 × 6 | None | S | NA | Liu et al[28] |

| 15 | 33 | M | 26 × 19 × 12 | Lymph node | S | 6 months | Montalvo et al[29] |

| 16 | 40 | F | 10.5 × 9.5 × 12.2 | Liver | S | NA | Zhou et al[30] |

| 17 | 67 | F | 14 × 12 × 7 | None | S | 5 months + | Our case |

In summary, despite its aggressive nature and poor prognosis, HS remains treatable. Early and definitive diagnosis is of paramount importance, and immunohistochemistry plays a pivotal role. Current treatment strategies, including che

The authors are grateful to the staff at the Department of Pathology of the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University (Guangdong Province, China).

| 1. | Mathé G, Gerard-Marchant R, Texier JL, Schlumberger JR, Berumen L, Paintrand M. The two varieties of lymphoid tissue "reticulosarcomas", histiocytic and histioblastic types. Br J Cancer. 1970;24:687-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang YC, Yu X, Li P, Zhao JJ, Sun L, Wang B. [Clinicopathological features of primary splenic histiocytic sarcoma:a case report and literature review]. Zhonghua Xueyexue Zazhi. 2010;31:663-666. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Kimura H, Nasu K, Sakai C, Shiga Y, Miyamoto E, Shintaku M, Wakatsuki S, Tominaga K, Abe M, Maruyama Y. Histiocytic sarcoma of the spleen associated with hypoalbuminemia, hypo gamma-globulinemia and thrombocytopenia as a possibly unique clinical entity--report of three cases. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;31:217-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Audouin J, Vercelli-Retta J, Le Tourneau A, Adida C, Camilleri-Broët S, Molina T, Diebold J. Primary histiocytic sarcoma of the spleen associated with erythrophagocytic histiocytosis. Pathol Res Pract. 2003;199:107-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Oka K, Nakamine H, Maeda K, Yamakawa M, Imai H, Tada K, Ito M, Watanabe Y, Suzuki H, Iwasa M, Tanaka I. Primary histiocytic sarcoma of the spleen associated with hemophagocytosis. Int J Hematol. 2008;87:405-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nangal JK, Kapoor A, Narayan S, Singhal MK, Beniwal S, Kumar HS. A case of CD68 negative histiocytic sarcoma of axilla masquerading as metastatic breast cancer. J Surg Case Rep. 2014;2014:rju071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen CJ, Williams EA, McAneney TE, Williams BJ, Mandell JW, Shaffrey ME. Histiocytic sarcoma of the cavernous sinus: case report and literature review. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2015;32:66-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Idbaih A, Mokhtari K, Emile JF, Galanaud D, Belaid H, de Bernard S, Benameur N, Barlog VC, Psimaras D, Donadieu J, Carpentier C, Martin-Duverneuil N, Haroche J, Feuvret L, Zahr N, Delattre JY, Hoang-Xuan K. Dramatic response of a BRAF V600E-mutated primary CNS histiocytic sarcoma to vemurafenib. Neurology. 2014;83:1478-1480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pan GZ, Xu JB, Yuan QZ. [Progress on diagnosis and treatment of histiocytic cell sarcoma]. Zhongguo Zhongliu Linchuang. 2016;43:220-222. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Ozkaya N, Jaffe ES. Current Concepts in Histiocytic Neoplasms. Adv Anat Pathol. 2025;32:272-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Liu S, Yang AH. [Research advances in the management of histiocytic sarcoma]. Zhongguo Aizheng Fangzhi Zazhi. 2018;10:250-253. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Zhu X, Wu W, Sun WY. [Histiocytic Sarcoma: A Case Report and Literature Review]. Zhejiang Shiyong Yixue. 2011;16:173-175. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Schlick K, Aigelsreiter A, Pichler M, Reitter S, Neumeister P, Hoefler G, Beham-Schmid C, Linkesch W. Histiocytic sarcoma - targeted therapy: novel therapeutic options? A series of 4 cases. Onkologie. 2012;35:447-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shukla N, Kobos R, Renaud T, Teruya-Feldstein J, Price A, McAllister-Lucas L, Steinherz P. Successful treatment of refractory metastatic histiocytic sarcoma with alemtuzumab. Cancer. 2012;118:3719-3724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vaughn JL, Freitag CE, Hemminger JA, Jones JA. BRAF (V600E) expression in histiocytic sarcoma associated with splenic marginal zone lymphoma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11:92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yang HL, Zhang YZ. [Research Advances in the Etiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Histiocytic Sarcoma]. Zhongguo Manxingbing Yufang Yu Kongzhi. 2018;26:540-542. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Tsujimura H, Miyaki T, Yamada S, Sugawara T, Ise M, Iwata S, Yonemoto T, Ikebe D, Itami M, Kumagai K. Successful treatment of histiocytic sarcoma with induction chemotherapy consisting of dose-escalated CHOP plus etoposide and upfront consolidation auto-transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2014;100:507-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pfankuche VM, Spitzbarth I, Lapp S, Ulrich R, Deschl U, Kalkuhl A, Baumgärtner W, Puff C. Reduced angiogenic gene expression in morbillivirus-triggered oncolysis in a translational model for histiocytic sarcoma. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:816-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pfankuche VM, Sayed-Ahmed M, Contioso VB, Spitzbarth I, Rohn K, Ulrich R, Deschl U, Kalkuhl A, Baumgärtner W, Puff C. Persistent Morbillivirus Infection Leads to Altered Cortactin Distribution in Histiocytic Sarcoma Cells with Decreased Cellular Migration Capacity. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Alberts P, Olmane E, Brokāne L, Krastiņa Z, Romanovska M, Kupčs K, Isajevs S, Proboka G, Erdmanis R, Nazarovs J, Venskus D. Long-term treatment with the oncolytic ECHO-7 virus Rigvir of a melanoma stage IV M1c patient, a small cell lung cancer stage IIIA patient, and a histiocytic sarcoma stage IV patient-three case reports. APMIS. 2016;124:896-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Franchino C, Reich C, Distenfeld A, Ubriaco A, Knowles DM. A clinicopathologically distinctive primary splenic histiocytic neoplasm. Demonstration of its histiocyte derivation by immunophenotypic and molecular genetic analysis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:398-404. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Kobayashi S, Kimura F, Hama Y, Ogura K, Torikai H, Kobayashi A, Ikeda T, Sato K, Aida S, Kosuda S, Motoyoshi K. Histiocytic sarcoma of the spleen: case report of asymptomatic onset of thrombocytopenia and complex imaging features. Int J Hematol. 2008;87:83-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yamada S, Tasaki T, Satoh N, Nabeshima A, Kitada S, Noguchi H, Yamada K, Takeshita M, Sasaguri Y. Primary splenic histiocytic sarcoma complicated with prolonged idiopathic thrombocytopenia and secondary bone marrow involvement: a unique surgical case presenting with splenomegaly but non-nodular lesions. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yamamoto Y, Hiasa Y, Hirooka M, Koizumi Y, Takeji S, Tokumoto Y, Tsubouchi E, Ikeda Y, Abe M, Matsuura B, Onji M. Complete response of a patient with advanced primary splenic histiocytic sarcoma by treatment with chemotherapeutic drugs selected using the collagen gel droplet-embedded culture drug sensitivity test. Intern Med. 2012;51:2893-2897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yamamoto S, Tsukamoto T, Kanazawa A, Shimizu S, Morimura K, Toyokawa T, Xiang Z, Sakurai K, Fukuoka T, Yoshida K, Takii M, Inoue K. Laparoscopic splenectomy for histiocytic sarcoma of the spleen. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;5:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Huang K, Columbie AF, Allan RW, Misra S. Thrombocytopenia with multiple splenic lesions - histiocytic sarcoma of the spleen without splenomegaly: A case report. World J Clin Oncol. 2020;11:162-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kobayashi M, Sugawara K, Suzaki K, Kosugi N. Primary splenic histiocytic sarcoma successfully treated with splenectomy: a case report and literature review. Int Cancer Conf J. 2022;11:201-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Liu YJ, Zhong JQ, Feng H. [A Case Report of Primary Splenic Histiocytic Sarcoma]. Shanxi Yiyao Zazhi. 2016;45:2723. |

| 29. | Montalvo N, Lara-Endara J, Redrobán L, Leiva M, Armijos C, Russo L. Primary splenic histiocytic sarcoma associated with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: A case report and review of literature of next-generation sequencing involving FLT3, NOTCH2, and KMT2A mutations. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2022;5:e1496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zhou Y, Zhang K, Yu C. A case of primary splenic histiocytic sarcoma with liver metastasis. Asian J Surg. 2024;47:4623-4624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/