Published online Jan 26, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i3.114521

Revised: October 27, 2025

Accepted: January 9, 2026

Published online: January 26, 2026

Processing time: 122 Days and 17.4 Hours

Postdural puncture headache (PDPH) is a significant complication of neuraxial procedures. Although conservative treatments and the invasive epidural blood patch (EBP) are currently standard approaches, the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) block is emerging as a promising, less-invasive alternative. The patho

To provide a comprehensive overview of current evidence regarding the use of the SPG block in treating PDPH, explores the anatomical and physiological basis of this intervention, describes various administration techniques for administering the block, and critically assesses the efficacy and safety data from clinical studies.

A systematic literature search was conducted on PubMed and the Cochrane Database to identify systematic reviews and meta-analyses published up to April 2025, using the keywords “sphenopalatine ganglion block” and “post-dural pun

The SPG block is a simple, noninvasive, and effective bedside procedure. Clinical studies have demonstrated that it provides rapid pain relief, with high success rates and an onset of action typically within 10-30 minutes. The most used te

Although EBP remains the preferred treatment for severe PDPH, the SPG block is a viable alternative for mild-to-moderate cases, often allowing patients to postpone or avoid EBP. Comparative studies suggest that SPG block has a quicker onset than EBP, though in some cases, it provides shorter duration relief. Overall, the SPG block is a safe, effective, and readily accessible treatment for PDPH. Its minimally invasive nature and high success rate in providing rapid pain relief make it an excellent first-line alternative to more invasive procedures. Further large-scale, standardized randomized controlled trials are required to optimize protocols and fully integrate the SPG block into mainstream clinical practice.

Core Tip: Postdural puncture headache (PDPH) is a debilitating complication of spinal anesthesia. Although the epidural blood patch remains the established gold standard invasive treatment, the sphenopalatine ganglion block has emerged as a promising minimally invasive alternative. Sphenopalatine ganglion block operates by interrupting the parasympathetic pathways responsible for cerebral vasodilation, which underlies PDPH. It provides rapid pain relief in majority of cases, with minimal side effects. Its ease of application and high success rate make it an excellent alternative, allowing patients to avoid or delay more invasive procedures such as epidural blood patch, particularly in cases of mild to moderate PDPH.

- Citation: Mahanty PR, Sen B, Anand R, Nag DS, Pahadi N, Lodh D, Upadhyaya T. Sphenopalatine ganglion block for postdural puncture headache: A review of current evidence. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(3): 114521

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i3/114521.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i3.114521

Postdural puncture headache (PDPH) is a frequent and often debilitating complication following dural puncture during procedures intentional procedures (e.g., spinal anesthesia, lumbar puncture) or unintentional ones (e.g., epidural an

A promising emerging intervention is the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) block (SPGB)[6,7]. The SPG, a peripheral parasympathetic ganglion located in the pterygopalatine fossa, serves as a hub for cranial autonomic innervation and has been implicated in the pathophysiology of cluster headache and trigeminal neuralgia[8]. Application of a local anesthetic to the SPG is thought to modulate cerebral blood flow and counteract the compensatory vasodilation underlying PDPH pain, thereby offering a novel therapeutic mechanism. Recent evidence supports its use for EBP-resistant PDPH[9]. The SPGB has recently been repurposed for PDPH management, with encouraging outcomes reported in case series and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The proposed mechanisms of PDPH relief include inhibition of parasympathetic outflow, reduction of cerebral vasodilation, and modulation of nociceptive signaling from the meninges. This review aims to achieve two objectives: First, to systematically review and compare findings from meta-analyses on the efficacy of established PDPH, particularly EBP and pharmacotherapy; and second, to determine the role of SPGB within an evidence-based treatment algorithm by evaluating its efficacy and safety based on data from meta-analyses.

The rationale for SPGB derives from the anatomy of the ganglion and the pathophysiology of PDPH. The SPG is a triangular parasympathetic structure situated in the pterygopalatine fossa, connected to the trigeminal and autonomic systems, and located posterior to the middle nasal turbinate and anterior to the pterygoid canal[10]. Also known as the pterygopalatine, Meckel, or nasal ganglion, it modulates cerebral vasodilation through parasympathetic fibers[11]. The Monro-Kellie doctrine provides the foundation for understanding PDPH: The total intracranial volume of brain tissue, blood, and CSF is fixed[12]. Persistent CSF leakage following dural puncture disrupts this equilibrium, triggering compensatory cerebral vasodilation to maintain intracranial volume as the parenchyma cannot expand to compensate. This vasodilation is the principal cause of pain. As the primary mediator of this vasodilatory response, the SPG is a logical target for intervention. Blocking its output with a local anesthetic is theorized to reduce vasodilation and thereby alleviate headache. Parasympathetic activity mediated by neurons with synapses in the SPG contributes to this va

The SPG can be approached using several techniques[9,11,13,14], each with distinct advantages and considerations (Table 1). The choice of technique depends on the operator’s experience, available equipment, and the clinical scenario, particularly whether a simple topical application or a more precise, image-guided injection is required. The comparative efficacy, duration of relief, and safety profiles among these techniques remain active areas of investigation and will be discussed in detail throughout this review.

| Technique | Ref. | Approach | Description | Key advantages | Key limitations/considerations |

| Trans nasal | Schaffer et al[13], 2015 | Topical | A cotton-tipped applicator, catheter, or atomizer is used to apply a local anesthetic (e.g., lidocaine) to the nasal mucosa; an anesthetic is applied to the posterior pharyngeal wall mucosa; the goal is to diffuse the medication to the underlying sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) | It is noninvasive and simple; quick to perform at the bedside; there is a low risk of serious complications; easily repeatable | Drug diffusion is inconsistent; shorter duration of the effect; the anesthetic dose is not precisely controlled; uncomfortable for patients |

| Transoral | Piagkou et al[11], 2012 | Invasive | The needle is advanced through the hard palatine’s greater palatine foramen; the needle enters the pterygopalatine fossa; local anesthetic is injected directly into SPG; it is often performed under fluoroscopic guidance | This allows for the precise injection of a known volume; provides a more consistent and prolonged effect | Invasive: Risk of vascular injury and hematoma; risk of infection |

| Suprazygomati | Alseoudy et al[9], 2024 | Invasive and ultrasound-guided | The needle is advanced superior to the zygomatic arch; the needle is guided to the pterygopalatine fossa to deliver anesthesia; the procedure is performed under real-time ultrasonographic guidance | Real-time visualization can improve the accuracy and safety of the procedure; it avoids radiation exposure | This requires significant ultrasound expertise and equipment; this is technically more challenging; risk of orbital injury |

| Infrazygomatic | Anthony Cometa et al[14], 2021 | Invasive and fluoroscopy-guided | The needle is advanced inferior to the zygomatic arch through the masseter muscle; fluoroscopic imaging is used to guide the needle into the pterygopalatine fossa; imaging confirmed correct needle placement before anesthetic administration | Direct visualization of the needle position using fluoroscopy; it confirms accurate needle placement | It involves radiation exposure for both patients and operators; it is invasive and carries the risk of vascular injury and hematoma; it can damage the surrounding nerves |

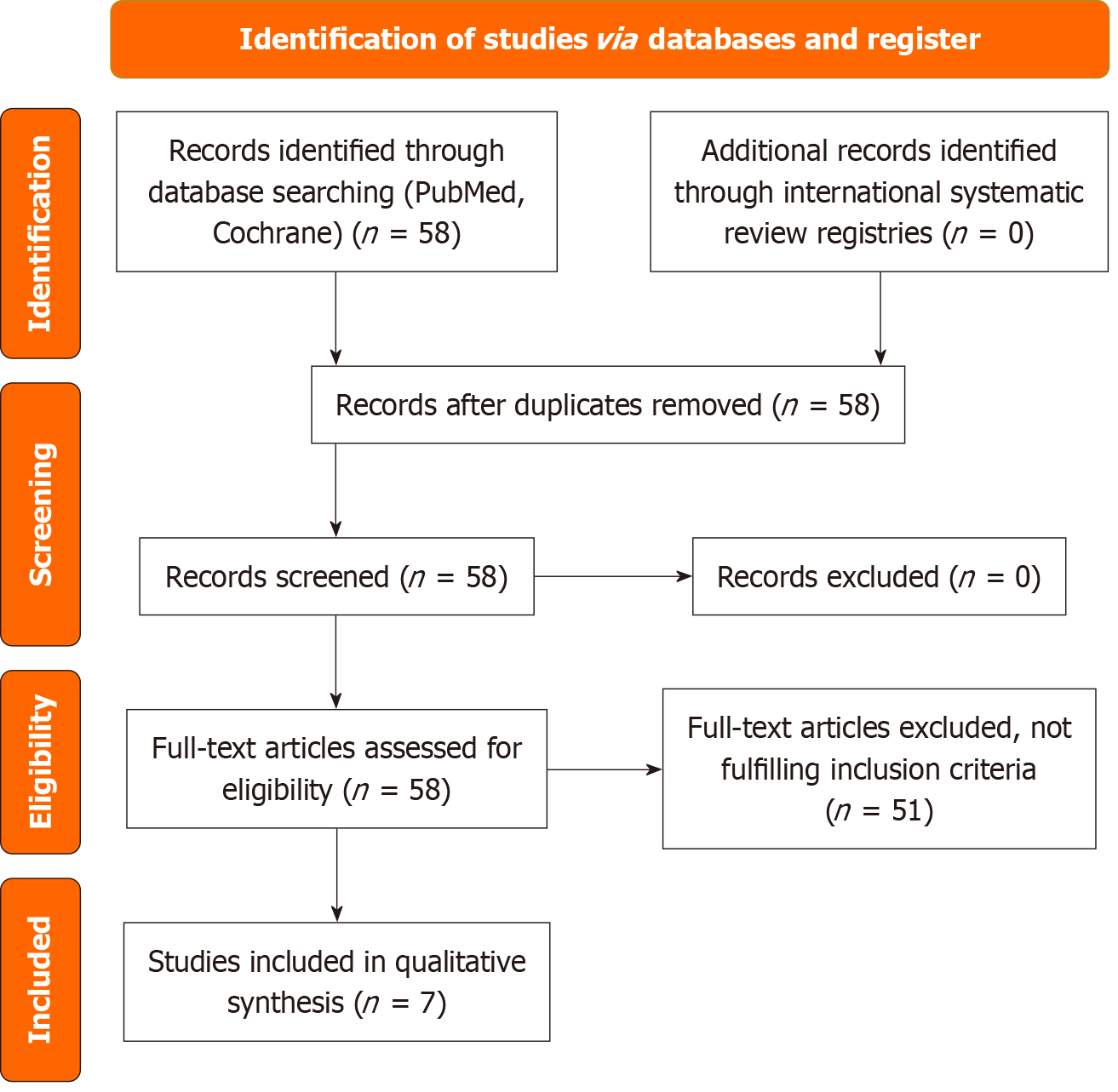

Search strategy and selection criteria: A systematic search was conducted in PubMed and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews for articles published from inception to April 1, 2025. The search strategy used a combined MeSH and free-text terms: (“post-dural puncture headache” OR “PDPH”) AND (“meta-analysis” OR “systematic review”) AND (“epidural blood patch” OR “caffeine” OR “gabapentin” OR “sphenopalatine ganglion block”). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Meta-analyses or systematic reviews of RCTs and/or observational studies; (2) Adult patients with PDPH; (3) Intervention, including any treatment for PDPH; and (4) Reported outcomes of headache cure or relief. For this review, only studies in which the population was restricted to adults (≥ 18 years) with a confirmed diagnosis of PDPH were included. Eligible studies had to report at least one of the following outcomes: Pain relief/intensity, time to symptom resolution, need for additional interventions, or adverse effects. An additional requirement was that the treated headache had to be a confirmed PDPH, not another headache type.

Data extraction and quality assessment: Two independent reviewers extracted data. Information on interventions, comparators, and effect estimates was obtained for the meta-analyses of conventional treatments. For studies addressing the SPGB, all available data on efficacy, safety, and techniques were extracted for qualitative analysis.

The initial search identified 58 records of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Of these, 51 were excluded for various reasons, including lack of a specific PDPH population, outcomes not relevant to the review, unclear intervention reporting, or absence of efficacy or safety data. Seven systematic reviews and meta-analyses were deemed eligible for the qualitative synthesis. After a comprehensive review of 58 PubMed results, seven articles were selected for further analysis. The study selection process is summarized in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses flow diagram (Figure 1). This assessment offers a thorough overview of the current evidence for managing PDPH by integrating findings from recent high-level systematic reviews and meta-analyses. To establish the evidence base, Table 2[3,15-20] presents a chronological summary of the key systematic reviews and meta-analyses of PDPH management. These reviews cover both pharmacological and interventional strategies for the prevention and treatment of PDPH. To further detail the specific outcomes of these studies, Table 3 provides a comprehensive breakdown of their efficacy and key findings, enabling direct comparison of the conclusions drawn by various authors[3,15-20]. Table 4 presents the consolidated efficacy summary of major PDPH interventions.

| Ref. | Type of review | Key focus | Included studies (n) | Key interventions | Main conclusion and finding |

| Basurto Ona et al[15], 2015 | Cochrane review | Pharmacological treatment | 13 RCTs | Caffeine, gabapentin, and theophylline | Evidence for the benefits of these drugs is limited owing to small, biased studies, although some drugs have shown promise |

| Barati-Boldaji et al[16], 2023 | Meta-analysis | Aminophylline/theophylline | 15 studies | Aminophylline, theophylline | They showed potential for treatment but not for prevention |

| Chang et al[17], 2021 | Meta-analysis | GON block (treatment) | 7 studies | Greater occipital nerve block | GONB is effective for short-term PDPH pain relief |

| Giaccari et al[18], 2021 | Systematic review | Nerve blocks (treatment) | 19 studies | SPG block, GONB, LON block | Peripheral nerve blocks are promising and safe options |

| Zhao et al[19], 2023 | Bayesian network meta analysis | Pharmacological prevention | 22 RCTs | Propofol, ondansetron, and amin | Propofol, ondansetron, and aminophylline were the most effective in reducing PDPH incidence |

| Dwivedi et al[20], 2023 | Meta-analysis | SPG block (treatment) | 9 RCTs | Trans-nasal SPG Block | The SPG block was effective for immediate pain relief compared to the controls, but the effect was short-lived |

| Alatni et al[3], 2024 | Systematic review | Multi-modal (treatment and prevention) | 38 studies | Pharmacologic, nerve blocks, EBP | Various effective strategies were summarized, and EBP was affirmed as the gold standard |

| Ref. | Key focus | Main conclusion and finding | Key interventions with positive outcomes | Key interventions with no significant effect |

| Basurto Ona et al[15], 2015 | Pharmacological treatment | However, evidence for the benefits was limited due to the small sample size and bias in the studies; some drugs were promising in reducing pain scores | Caffeine: Reduced PDPH persistence compared to placebo; gabapentin: Better VAS scores vs placebo/ergotamine; hydrocortisone: Better VAS scores than conventional treatment/placebo; theophylline: Better VAS scores than acetaminophen/conservative treatment | Sumatriptan and ACTH: No relevant effect on pain scores |

| Barati-Boldaji et al[16], 2023 | Aminophylline/theophylline (Tx and prevention) | Therapeutic use significantly reduced pain scores (moderate evidence); prophylactic use did not significantly reduce the PDPH risk (very low evidence) | Aminophylline/theophylline: Effective for pain relief compared to placebo or conventional therapy | Aminophylline: Not effective for prevention |

| Chang et al[17], 2021 | GON block (treatment) | GONB was effective for short-term pain relief at 1, 6, and 24 hours and reduced intervention failure | Greater occipital nerve block (GONB): Effective for pain relief; steroid co-administration may extend this effect | N/A |

| Giaccari et al[18], 2021 | Nerve blocks (treatment) | Peripheral nerve blocks (SPG, GON, and LON) were effective, safe, and significantly reduced pain scores | SPG, GON, LON blocks: Effective analgesic options | N/A |

| Zhao et al[19], 2023 | Pharmacological prevention (obstetric) | Propofol, ondansetron, and aminophylline were the most effective in reducing PDPH incidence; propofol and ondansetron also reduced PONV | Propofol (PPF), ondansetron (OND), and aminophylline (AMP) are effective; gabapentin/pregabalin (GBP/PGB): Effective at 48 hours | Dexamethasone, hydrocortisone: No superiority over placebo; no therapy reduced headache severity |

| Dwivedi et al[20], 2023 | SPG block (treatment) | SPG block was effective for immediate, short-term pain relief (up to 6 hours) vs conservative treatment and lignocaine puffs | Transnasal SPG block: Effective for short-term relief | It was not superior to the sham or GON blocks; effects were not sustained beyond 6 hours |

| Alatni et al[3], 2024 | Multi-modal (Tx and prevention) | Various effective strategies have been summarized, and EBP remains the gold standard; nerve blocks are effective and less invasive | Oral pregabalin and intravenous (IV) aminophylline are effective for the treatment and prevention of migraine headaches; IV Mannitol, IV hydrocortisone, neostigmine + atropine, SPG/GON blocks: Effective; fibrin glue, smaller needles: Effective prevention; EBP: Gold standard | Neuraxial morphine, epidural dexamethasone: Questionable for prevention |

| Ref. | Intervention | Primary use | Efficacy for PDPH prevention | Efficacy for PDPH treatment | Key findings and notes | Common/notable side effects |

| Alatni et al[3], 2024; Barati-Boldaji et al[16], 2023 | Aminophylline/theophylline | Treatment and prevention | Mixed (not recommended): A meta-analysis found no significant benefit of prophylaxis (very low evidence) | Effective (recommended): Significantly reduced pain scores (moderate evidence); this effect is enhanced when combined with dexamethasone | Considered a primary pharmacological option for treating established PDPH; the efficacy of prevention is not well supported | No significant adverse events were reported in the studies |

| Basurto Ona et al[15], 2015 | Caffeine | Treatment | It is not typically used for prevention | Effective (recommended): Reduces the persistence of PDPH and the need for rescue interventions compared to placebo | A classic and well-established treatment for PDPH | Well tolerated; no major side effects were reported in the review |

| Alatni et al[3], 2024; Basurto Ona et al[15], 2015; Zhao et al[19], 2023 | Gabapentin/pregabalin | Treatment and prevention | Effective (potential): Pregabalin has a preventive effect; gabapentin/pregabalin reduced incidence at 48 hours | Effective (recommended): Superior to placebo and ergotamine + caffeine in reducing pain scores over several days | Oral pregabalin has been highlighted as being particularly effective for both treatment and prevention | Generally well tolerated; sedation was mentioned but not quantitatively synthesized |

| Zhao et al[19], 2023 | Ondansetron (OND) | Prevention | Effective (recommended): Significantly reduces the cumulative incidence of PDPH | Not assessed for treatment in these reviews | It also significantly reduces the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) | It may induce migraine headaches in patients with a history of migraine (case reports) |

| Zhao et al[19], 2023 | Propofol (PPF) | Prevention | Most effective (recommended): Ranked as the most effective prophylactic drug for reducing incidence | Not assessed for treatment in these reviews | Also significantly reduces the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) | Sedation, diplopia, and tinnitus were mentioned in individual studies |

| Basurto Ona et al[15], 2015; Zhao et al[19], 2023 | Corticosteroids (dexamethasone, hydrocortisone) | Treatment and prevention | Not effective: Dexamethasone did not show superiority in prevention (hydrocortisone did not show any significant prophylactic effects) | Effective for treatment: Hydrocortisone (IV) combined with conventional treatment led to better pain scores | Hydrocortisone is effective for treatment but not for prevention; the utility of dexamethasone remains questionable | No clinically significant adverse events were reported |

| Chang et al[17], 2021 | Greater occipital nerve block (GONB) | Treatment | N/A | Effective (recommended): Provides significant short-term pain relief (1 hour, 6 hours, 24 hours) and reduces intervention failure | A feasible, less invasive alternative to EBP; steroid coadministration may prolong analgesic effects | No major adverse events were reported. Minor local discomfort |

| Dwivedi et al[20], 2023 | Sphenopalatine ganglion block (SPGB) | Treatment | N/A | Effective (short-term): Superior to conservative care for immediate pain relief (up to 6 hours); not superior to sham or GONB | The effects are immediate but short-lived; it was not superior to the other nerve blocks | Nasal discomfort, throat numbness, and unpleasant taste (minor and transient) |

| Alatni et al[3], 2024 | Epidural blood patch (EBP) | Treatment | N/A | Highly effective (gold standard): The ultimate solution for patients failing medical therapy | It rapidly decreases headache intensity; approximately 20% may require a second procedure; it is more invasive than pharmacological or nerve block options | Risks associated with neuraxial procedures (e.g., infection, repeat dural puncture) |

| Alatni et al[3], 2024 | Fibrin glue | Prevention | Effective (promising): Significantly reduced PDPH incidence and duration in the reviewed evidence | N/A | A novel preventive strategy has been noted for its promising safety and affordability | Not explicitly stated; however, the reviewed evidence noted a good safety profile |

The synthesis of evidence indicates a comprehensive approach for PDPH management, presenting several efficacious strategies for both prevention and treatment. In terms of prophylaxis, pharmacological agents such as propofol, ondansetron, and aminophylline have demonstrated effectiveness, while fibrin glue has emerged as a promising non-pharmacological alternative. For the treatment of established PDPH, EBP remains the definitive, gold-standard in

According to the 2023 Multisociety International Consensus Statement, establishing a standardized treatment protocol for PDPH is essential to improve outcomes[2]. The consensus emphasized the importance of risk assessment and the use of non-cutting spinal needles to reduce the PDPH incidence. Treatment should begin with conservative measures, such as hydration and multimodal analgesia, progressing to an EBP for severe or refractory cases. The consensus did not recommend the routine use of the SPGB for PDPH because of insufficient evidence, resulting in a grade I recom

Recent case reports, case series, and small trials have indicated a favorable role of SPGB and GONB in the management of PDPH. We conducted a comparative evaluation of SPGB and other treatment modalities to objectively assess the accumulation of evidence. We conducted a comparative evaluation of SPGB and other treatment modalities to objectively assess the accumulation of evidence. Previously systematic review by Albaqami et al[21] estimated that SPGB is a highly effective treatment for PDPH in the obstetric population. Albaqami et al’s analysis[21] specifically reported that 60.3% of patients achieved significant and complete relief without the need for further intervention. Another study demonstrated a significant reduction in the requirement for rescue analgesia, as well as a notable increase in the time interval before the demand for rescue analgesia, when compared to the placebo group[22]. Peripheral nerve blocks, including SPGB and GONB, offer an intermediate option; further evidence is required to establish their precise role relative to standard interventions. Recent publications advocate reevaluating the PDPH treatment algorithm to incorporate GONB and SPGB as potential methods to reduce EBP use[17,20]. Given its technical simplicity, fast onset, and ease of bedside application, SPGB offers a notable practical advantage.

Our review presents a more favorable assessment of SPGB compared with the 2023 Consensus Statement, which issued a grade I recommendation against its routine use due to limited evidence[2]. This difference likely reflects the inclusion of more recent meta-analyses, such as the 2023 meta-analysis study by Dwivedi et al[20], which provided higher-grade evidence for short-term efficacy and faster relief compared to conservative treatment. Although the consensus correctly notes the lack of large-scale, definitive trials, our interpretation of the cumulative emphasized the practical value of SPGB as a rapid, low-risk bridging intervention, especially when other options are unavailable. Reconciling these perspectives highlights the need for the large, high-quality RCTs to strengthen the evidence base.

The primary advantage of the transnasal SPGB lies in its rapid onset and minimally invasive nature. Dwivedi et al[20] confirmed its superiority over conservative treatments for immediate pain relief, making it an excellent option for urgent symptom control when invasive procedures are not feasible. Its ease of administration allows quick use across various clinical settings, even where anesthesia support for EBP may not be limited. However, its main limitation is the short duration of efficacy. The same analysis found that its benefits often dissipate after 6 hours, and SPGB was not superior to sham blocks or GONB in sustained pain relief. Thus, SPGB should be regarded as a bridging therapy rather than a definitive cure. It provides short-term symptom control while awaiting the effect of pharmacological treatments (e.g., aminophylline, gabapentin) or arranging a more durable intervention.

Vs pharmacological therapy: Drugs such as aminophylline (for treatment) and propofol or ondansetron (for prevention) provide systemic and longer-lasting effects once therapeutic levels are achieved, but their onset is delayed. SPGB offers immediate relief but with a limited duration. These modalities are complementary: SPGB can manage the acute sy

Vs GONB: Evidence from Chang et al[17] suggests that GONB may be a more effective and longer-lasting intervention than SPGB. GONB provided significant pain relief sustained for up to 24 hours and reduced the need for rescue in

Vs EBP: EBP remains the gold standard for definitive PDPH treatment due to its high success rate and lasting effect. SPGB cannot replace EBP in refractory cases, but serves as a valuable option for patients who are not candidates for EBP (e.g., due to coagulopathy, infection, or patient refusal). It also provides temporary comfort during the waiting period before EBP administration.

The introduction of SPGB and GONB has expanded the therapeutic options for PDPH management. Nevertheless, clinical decision-making should remain patient-centered and evidence-based. The 2023 Consensus Statement does not support the routine use of SPGB due to insufficient evidence (grade I, low certainty). While SPGB offers rapid relief for acute pain and has a minimally invasive nature, its efficacy remains less established than that of EBP. For sustained symptom control, GONB or EBP remains a superior treatment modality. SPGB or GONB should primarily be considered when EBP is contraindicated or unavailable. These nerve blocks should complement, not replace, first-line evidence-based treatments and should be performed by trained clinicians. Future studies employing standardized SPGB techniques and outcome measures may strengthen its evidence base and clinical acceptability.

This systematic review has several limitations stemming from the available literature and methodological variability. Limited High-Quality Studies: Evidence supporting SPGB for PDPH mainly comes from small trials and case series, with few large RCTs, limiting the strength of the recommendation.

Methodological heterogeneity: Studies varied in diagnostic criteria, SPGB techniques, comparison groups, and outcome measures, limiting synthesis and comparability.

Short-term focus: Most studies assessed only short-term outcomes, with limited data beyond 6 hours compared with EBP or GONB.

Publication bias: Positive findings may be overrepresented, while negative or null results are underreported.

Limited safety data: Although only minor adverse effects have been reported, systematic long-term safety evaluations are lacking.

These limitations underscore the need for larger, standardized RCTs to better inform PDPH management. Ad

SPGB represents a valuable adjunct in PDPH management due to its rapid and minimally invasive nature. It serves primarily as a bridging therapy for acute symptom control rather than a first-line, standalone, or definitive treatment. SPGB’s greatest utility lies in providing immediate relief while awaiting the effects of pharmacological interventions or when EBP is contraindicated. Among peripheral nerve blocks, current evidence favours GONB for its longer-lasting benefits. Future head-to-head RCTs comparing SPGB, GONB, and standard pharmacological treatments are essential to define their optimal sequencing and integration into the PDPH treatment algorithm.

| 1. | Chekol B, Yetneberk T, Teshome D. Prevalence and associated factors of post dural puncture headache among parturients who underwent cesarean section with spinal anesthesia: A systemic review and meta-analysis, 2021. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;66:102456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Uppal V, Russell R, Sondekoppam R, Ansari J, Baber Z, Chen Y, DelPizzo K, Dîrzu DS, Kalagara H, Kissoon NR, Kranz PG, Leffert L, Lim G, Lobo CA, Lucas DN, Moka E, Rodriguez SE, Sehmbi H, Vallejo MC, Volk T, Narouze S. Consensus Practice Guidelines on Postdural Puncture Headache From a Multisociety, International Working Group: A Summary Report. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2325387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Alatni RI, Alsamani R, Alqefari A. Treatment and Prevention of Post-dural Puncture Headaches: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2024;16:e52330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bezov D, Ashina S, Lipton R. Post-dural puncture headache: Part II--prevention, management, and prognosis. Headache. 2010;50:1482-1498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kapan A, Waldhör T, Schiffler T, Beck J, Wöber C. Health-related quality of life, work ability and disability among individuals with persistent post-dural puncture headache. J Headache Pain. 2024;25:64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cohen S, Trnovski S, Zada Y. A new interest in an old remedy for headache and backache for our obstetric patients: a sphenopalatine ganglion block. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:606-607. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Babaiyan S, Shakhs Emampour F. Avoiding Invasive Measures: Sphenopalatine Ganglion Block as a Substitute for Epidural Blood Patch in Post-dural Puncture Headache: A Case Report. Anesth Pain Med. 2024;14:e148291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Puthenveettil N, Rajan S, Mohan A, Paul J, Kumar L. Sphenopalatine ganglion block for treatment of post-dural puncture headache in obstetric patients: An observational study. Indian J Anaesth. 2018;62:972-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Alseoudy MM, Abd-Elmoaty WA, Ramzy EA, Abdelbaser I, El-Emam EM. Ultrasound-Guided Suprazygomatic Sphenopalatine Ganglion Block for Postdural Puncture Headache Resistant to Epidural Blood Patch: A Case Report. A A Pract. 2024;18:e01778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Khonsary SA, Ma Q, Villablanca P, Emerson J, Malkasian D. Clinical functional anatomy of the pterygopalatine ganglion, cephalgia and related dysautonomias: A review. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4:S422-S428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Piagkou M, Demesticha T, Troupis T, Vlasis K, Skandalakis P, Makri A, Mazarakis A, Lappas D, Piagkos G, Johnson EO. The pterygopalatine ganglion and its role in various pain syndromes: from anatomy to clinical practice. Pain Pract. 2012;12:399-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mokri B. The Monro-Kellie hypothesis: applications in CSF volume depletion. Neurology. 2001;56:1746-1748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 592] [Cited by in RCA: 658] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Schaffer JT, Hunter BR, Ball KM, Weaver CS. Noninvasive sphenopalatine ganglion block for acute headache in the emergency department: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65:503-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Anthony Cometa M, Zasimovich Y, Smith CR. Percutaneous sphenopalatine ganglion block: an alternative to the transnasal approach. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2021;45:163-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Basurto Ona X, Osorio D, Bonfill Cosp X. Drug therapy for treating post-dural puncture headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD007887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Barati-Boldaji R, Shojaei-Zarghani S, Mehrabi M, Amini A, Safarpour AR. Post-dural puncture headache prevention and treatment with aminophylline or theophylline: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul). 2023;18:177-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chang YJ, Hung KC, Chen IW, Kuo CL, Teng IC, Lin MC, Yew M, Liao SW, Wu CY, Yu CH, Lan KM, Sun CK. Efficacy of greater occipital nerve block for pain relief in patients with postdural puncture headache: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e28438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Giaccari LG, Aurilio C, Coppolino F, Pace MC, Passavanti MB, Pota V, Sansone P. Peripheral Nerve Blocks for Postdural Puncture Headache: A New Solution for an Old Problem? In Vivo. 2021;35:3019-3029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhao G, Song G, Liu J. Efficacy of pharmacological therapies for preventing post-dural puncture headaches in obstetric patients: a Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23:215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dwivedi P, Singh P, Patel TK, Bajpai V, Kabi A, Singh Y, Sharma S, Kishore S. Trans-nasal sphenopalatine ganglion block for post-dural puncture headache management: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2023;73:782-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Albaqami MS, Alwarhi FI, Alqarni AA. The efficacy of sphenopalatine ganglion block for the treatment of postdural puncture headache among obstetric population. Saudi J Anaesth. 2022;16:45-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jespersen MS, Jaeger P, Ægidius KL, Fabritius ML, Duch P, Rye I, Afshari A, Meyhoff CS. Sphenopalatine ganglion block for the treatment of postdural puncture headache: a randomised, blinded, clinical trial. Br J Anaesth. 2020;124:739-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/