Published online Jan 6, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i1.112880

Revised: September 30, 2025

Accepted: December 18, 2025

Published online: January 6, 2026

Processing time: 150 Days and 16.6 Hours

It is challenging to diagnose isolated hyperbilirubinemia with rare and complex etiologies under the constraints of traditional testing conditions. Herein, we pre

We present a rare case of coexisting GS and EPP in a 23-year-old Chinese male with a long history of jaundice and recently found splenomegaly. Serial non-specific hemolysis screening tests yielded inconsistent results, and investigations for common hemolytic etiologies were negative. However, Levitt’s carbon mono

The rapid, non-invasive Levitt’s carbon monoxide breath test resolved the diag

Core Tip: This first-reported case of coexisting Gilbert syndrome and erythropoietic protoporphyria highlights Levitt’s carbon monoxide breath test as a pivotal non-invasive tool for diagnosing rare and complex causes of hyperbilirubinemia. The test confirmed severely shortened red blood cell lifespan (11 days), resolving diagnostic uncertainty after conventional tests failed, and guided definitive genetic diagnosis of dual uridine diphosphate glucuronosyl transferase 1A1 and ferrochelatase mutations.

- Citation: Kang LL, Zhang HD. Key role of Levitt’s carbon monoxide breath test in revealing coexistent Gilbert syndrome and erythropoietic protoporphyria: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(1): 112880

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i1/112880.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i1.112880

Isolated hyperbilirubinemia, characterized by elevated bilirubin without evidence of liver injury or cholestasis, arises from three mechanisms: (1) Increased bilirubin production (e.g., hemolysis); (2) Impaired hepatocellular uptake/conjugation (e.g., Gilbert syndrome (GS), the most common hereditary unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia); and (3) Reduced bilirubin secretion (e.g., Dubin-Johnson syndrome)[1]. While GS is common (prevalence: 6%-12%), ery

A 23-year-old Chinese male with a long-standing history of benign jaundice and a three-month history of splenomegaly was referred from a hematology clinic to our hospital’s gastroenterology department for further evaluation.

During each physical examination or medical visit, he had always been informed that it was constitutional jaundice and no treatment was required. Nevertheless, during a routine health check three months ago, an ultrasound surprisingly detected splenomegaly, which had never been present before. This discovery led to his referral to a hematology clinic for further assessment. The patient was uncertain whether any of his family members had a history of either jaundice or splenomegaly.

The patient had maintained overall good health since childhood, with the exception of mild yellowing of the eyes, which had persisted since it first appeared at the age of 7-8 years. He had no history of smoking, alcohol use, or drug abuse and enjoyed running.

A telephone interview with the patient’s parents, who lived hundreds of kilometers away in a rural area, revealed that neither parent experienced photosensitivity, but the father had a history of “yellow eyes” since his youth.

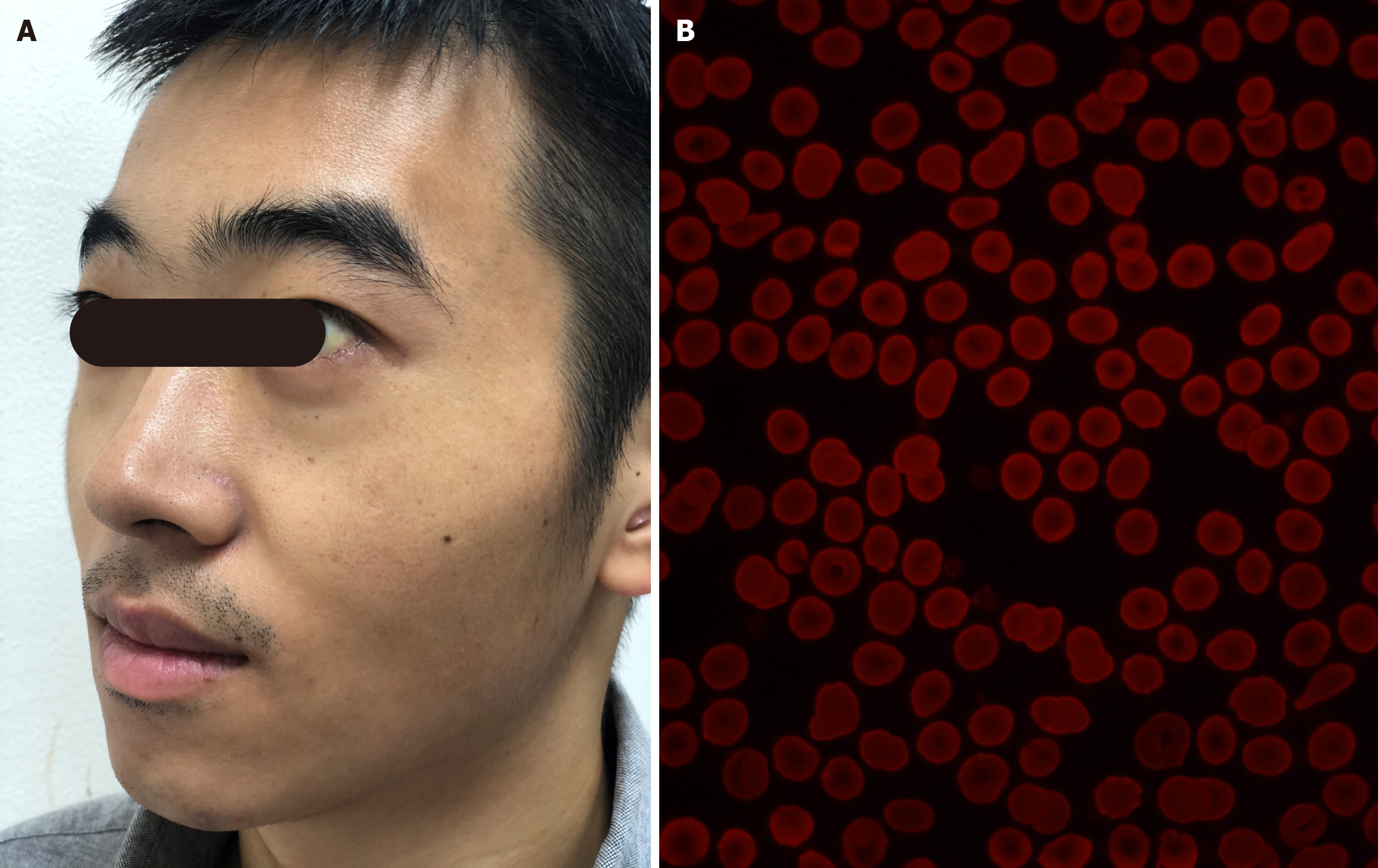

In the clinic, the physical examination revealed mild icterus of the sclera (Figure 1A) and a spleen palpable just 1.0 cm below the left costal margin.

Primary laboratory findings showed mild normocytic anemia (hemoglobin 11.6 g/dL) with a significantly elevated reticulocyte count (10.5%). Additionally, there was isolated unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia with a total bilirubin of 75.4 μmol/L, direct bilirubin of 6.7 μmol/L, and indirect bilirubin of 68.7 μmol/L. Other parameters were within normal limits, including albumin (4.0 g/dL), globulin (2.0 g/dL), liver enzymes (alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and gamma-glutamyl transferase), serum haptoglobin, and LDH levels. Given these find

Given the negative work-up, the patient was referred to our hospital’s gastroenterology department for further ev

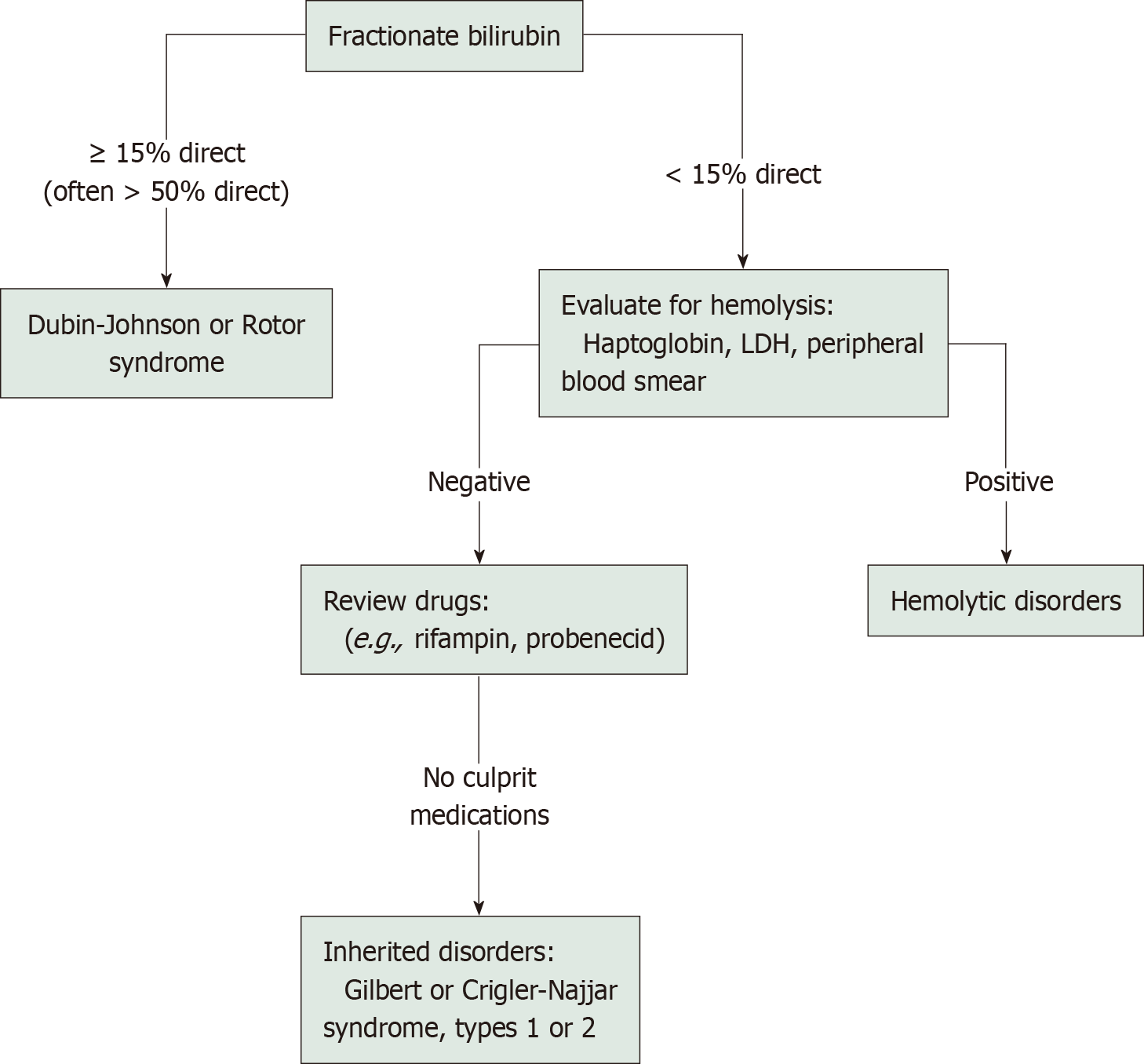

Subsequently, drawing from our previous similar experiences, and considering the patient’s long history of benign jaundice, negative results from common hemolytic etiology tests, and the discordance between significant unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia and mild anemia, we chose to perform targeted diagnostic next-generation sequencing using a commercial sequencing panel (MyGenotics, Beijing, China)[7]. This panel covered 208 genes associated with hereditary erythroid disorders, as well as the gene encoding UDP-glucuronosyltransferase family 1 member A1 (UGT1A1). The results revealed a homozygous mutation in the ferrochelatase (FECH) gene (c.315-48T>C) combined with a heterozygous mutation in the UGT1A1 gene (c.-3279T>G). Congenital mutation in the UGT1A1 gene is known to cause the most common hereditary unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, namely GS, while the FECH gene mutation is responsible for EPP, a rare inborn error of heme biosynthesis, characterized by the accumulation of photosensitive protoporphyrin in RBCs, hepatocytes, and vascular endothelium, which can lead to painful, non-blistering photodermatitis and/or hemolysis and hepatopathy in some cases. The genetic test indicated a comorbidity of GS and EPP. Genetic analysis of mailed blood samples showed that both parents carried the identical homozygous FECH mutation as the proband, with the same UGT1A1 mutation found in the father. The following was straightforward. A second round of medical history collection and physical examination was conducted. Although the patient denied any history of painful photosensitivity since childhood and a careful skin examination revealed no pigmentation or scarring in sun-exposed areas, further laboratory tests were consistent with EPP, including a large number of red-fluorescent RBCs in the peripheral blood smear under RBC fluorescence microscopy (Figure 1B).

No relevant imaging examinations have been performed.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was coexisted GS and EPP.

The patient was advised to avoid sunlight.

The patient was scheduled for annual consultations.

The prevalence of GS in the population ranges as high as from 6% to 12%, while the estimated prevalence of EPP, despite being the most common form of porphyria in children, is reported to be as low as 1 in 75000 to 1 in 200000 individuals[8,9]. Consequently, the likelihood of having both GS and EPP together would be exceedingly rare. Furthermore, just a fraction of EPP patients, particularly in Asian populations, carry the c.315-48T>C low-expression allele without an additional severe FECH mutation in trans. Such patients, whether heterozygous or homozygous, tend to experience a later onset and mild symptoms, often with less severe or even absent photosensitivity[9-11]. Therefore, the case we encountered of a 23-year-old male is indeed exceptional. Although quantitative EPP measurement - a diagnostic gold standard - was unavailable in our clinical setting, the diagnosis was unequivocally established by integrating genetic test results with functional evidence of hemolysis from Levitt’s CO breath test. This case highlights the practical value of such a combinatorial diagnostic approach, particularly in settings where specialized assays are not readily accessible.

Despite its rarity, however, this case still falls within the category of chronic isolated hyperbilirubinemia, a common clinical laboratory finding in gastroenterology[1]. It is characterized by elevated serum bilirubin levels in the context of normal global liver function, with no significant biochemical markers indicating hepatocellular injury or cholestasis[1]. It is well known that chronic isolated hyperbilirubinemia arises from one or more of the following three bilirubin metabolism mechanisms: (1) Increased bilirubin production (common, due to various intra- or extra-hemolysis); (2) Decreased hepatocellular uptake and conjugation of unconjugated bilirubin (most common, due to hereditary ab

Hemolysis is defined as the accelerated destruction of RBCs, leading to their premature removal from circulation and a shortened lifespan[2]. This means that a shortened RBC lifespan is a fundamental characteristic of hemolysis and a gold-standard diagnostic indicator. However, RBC lifespan measurement is seldom conducted in basic research or clinical practice due to the cumbersome and protracted nature of classical RBC labeling methods (e.g., 51Cr, 15N-glycine, or biotin), which can take several weeks or even months. Based on the understanding that exhaled endogenous CO mainly comes from degraded hemoglobin following RBC destruction, established mainly by Coburn and Forman[12], Levitt’s team[3,4] developed a simple, rapid CO breath test to estimate RBC lifespan in 1992, which was later modified in 2003. Studies have confirmed that Levitt’s CO breath test yields results similar to those obtained with classical labeling methods[3,5,6]. This innovation greatly simplifies the diagnostic process for hemolysis. When it comes to isolated hyperbilirubinemia, re

Clearly, with Levitt’s CO breath test, the challenges encountered in the differential diagnosis of isolated hyperbilirubinemia are no longer focused on confirming or excluding hemolysis, but rather on determining whether hemolysis is the sole cause or one of the contributing factors, followed by the selection of appropriate diagnostic tests to investigate the underlying etiology. Our previous study found that significantly elevated bilirubin levels, along with mild RBC lifespan shortening or relatively higher hemoglobin concentrations, often indicated mild hemolysis in GS or a multifactorial cause of hyperbilirubinemia, such as hemolysis combined with GS, as observed in this case[7].

Levitt’s CO breath test, being rapid and simple, greatly facilitates the differential diagnosis of rare and complex causes of hyperbilirubinemia, as it can sensitively and specifically diagnose the presence or absence of hemolysis.

| 1. | Pratt DS. Liver chemistry and function tests. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt, LJ, editors. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunder, 2021: 1154-1163. |

| 2. | Thiagarajan P, Prchal J. Erythrocyte turnover. In: Kaushansky K, Prchal JT, Press OW, Lichtman MA, Levi M, Burns LJ, Caligiuri MA, editors. Williams Hematology. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2016: 495. |

| 3. | Strocchi A, Schwartz S, Ellefson M, Engel RR, Medina A, Levitt MD. A simple carbon monoxide breath test to estimate erythrocyte turnover. J Lab Clin Med. 1992;120:392-399. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Furne JK, Springfield JR, Ho SB, Levitt MD. Simplification of the end-alveolar carbon monoxide technique to assess erythrocyte survival. J Lab Clin Med. 2003;142:52-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang HD, Ma YJ, Liu QF, Ye TZ, Meng FY, Zhou YW, Yu GP, Yang JP, Jiang H, Wang QS, Li GP, Ji YQ, Zhu GL, Du LT, Ji KM. Human erythrocyte lifespan measured by Levitt's CO breath test with newly developed automatic instrument. J Breath Res. 2018;12:036003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ye L, Ji Y, Zhou C, Luo J, Zhang L, Jing L, Zhao X, Guo J, Gao Q, Peng G, Li Y, Li Y, Li J, Fan H, Yang W, Yang Y, Ma Y, Zhang F. Comparison of Levitt's CO breath test and the (15) N-glycine labeling technique for measuring the lifespan of human red blood cells. Am J Hematol. 2021;96:1232-1240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kang LL, Liu ZL, Han QS, Chen YW, Liu LW, Xie XH, Luo JF, Ji YQ, Zhu GL, Ma YJ, Ji KM, Zhang HD. Levitt's CO breath test in the differential diagnosis of chronic isolated hyperbilirubinemia. J Breath Res. 2022;16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Balwani M. Erythropoietic Protoporphyria and X-Linked Protoporphyria: pathophysiology, genetics, clinical manifestations, and management. Mol Genet Metab. 2019;128:298-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mizawa M, Makino T, Nakano H, Sawamura D, Shimizu T. Erythropoietic Protoporphyria in a Japanese Population. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:634-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gouya L, Puy H, Robreau AM, Bourgeois M, Lamoril J, Da Silva V, Grandchamp B, Deybach JC. The penetrance of dominant erythropoietic protoporphyria is modulated by expression of wildtype FECH. Nat Genet. 2002;30:27-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gouya L, Martin-Schmitt C, Robreau AM, Austerlitz F, Da Silva V, Brun P, Simonin S, Lyoumi S, Grandchamp B, Beaumont C, Puy H, Deybach JC. Contribution of a common single-nucleotide polymorphism to the genetic predisposition for erythropoietic protoporphyria. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:2-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Coburn RF, Forman HJ. Carbon Monoxide Toxicity. Compr Physiol. 1987. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/